Abstract

Activation of renal peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) is renoprotective, but there is no safe PPARα activator for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Studies have reported that irbesartan (Irbe), an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) widely prescribed for CKD, activates hepatic PPARα. However, Irbe’s renal PPARα-activating effects and the role of PPARα signalling in the renoprotective effects of Irbe are unknown. Herein, these aspects were investigated in healthy kidneys of wild-type (WT) and Ppara-null (KO) mice and in the murine protein-overload nephropathy (PON) model respectively. The results were compared with those of losartan (Los), another ARB that does not activate PPARα. PPARα and its target gene expression were significantly increased only in the kidneys of Irbe-treated WT mice and not in KO or Los-treated mice, suggesting that the renal PPARα-activating effect was Irbe-specific. Irbe-treated-PON-WT mice exhibited decreased urine protein excretion, tubular injury, oxidative stress (OS), and pro-inflammatory and apoptosis-stimulating responses, and they exhibited maintenance of fatty acid metabolism. Furthermore, the expression of PPARα and that of its target mRNAs encoding proteins involved in OS, pro-inflammatory responses, apoptosis and fatty acid metabolism was maintained upon Irbe treatment. These renoprotective effects of Irbe were reversed by the PPARα antagonist MK886 and were not detected in Irbe-treated-PON-KO mice. These results suggest that Irbe activates renal PPARα and that the resultant increased PPARα signalling mediates its renoprotective effects.

Keywords: angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker, fatty acid metabolism, irbesartan (Irbe), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα)

INTRODUCTION

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) is a member of the steroid/nuclear receptor superfamily and is distributed to fatty acid-consuming organs including the kidney and liver [1,2]. PPARα activation increases the expression of its target genes encoding enzymes involved in fatty acid transport and metabolism. In kidney, PPARα is mainly expressed in the proximal tubular epithelial cells (PTECs), and maintains energy ho moeostasis and tubular absorptive function [3]. Kidney injury decreases renal PPARα expression, and PPARα agonist-induced renal PPARα activation exerted tubular-protective effects in murine models [4,5]. Furthermore, renal PPARα activation might suppress the progression of renal fibrosis and the decline of kidney function in chronic kidney disease (CKD) [6].

Among the known PPARα agonists, fibrates are used clinically in the treatment of hyperlipidaemia [7]. Fenofibrate could suppress microalbuminuria in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) nephropathy, suggesting a potential decrease in the glomerular filtration rate loss [8–10]. However, the serum concentration of fibrates in CKD patients is markedly increased and is frequently followed by renal toxicity [10]. Currently, safe clinical methods for activating renal PPARα in CKD patients have not been established.

Two angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), telmisartan (Tel) and irbesartan (Irbe) are well known for their partial agonist activity for PPARγ [11–15]. In addition, Tel and Irbe can also activate hepatic PPARα [16,17]. However, whether they activate renal PPARα is not well understood. Irbe shows high renal distribution; therefore, Irbe might activate renal PPARα [18]. Irbe is widely used in CKD patients as a valuable antihypertensive medicine by suppressing the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAS). Several randomized control trials using Irbe demonstrated significant renoprotection independent of Irbe’s antihypertensive effects in DM patients [19,20]. Renal PPARα activation by Irbe may contribute to these effects, but Irbe’s renal PPARα-activating effects and the role of PPARα signalling in the renoprotective effects of Irbe are unknown.

The present study shows that Irbe treatment could activate renal PPARα and exerted renoprotective effects via renal PPARα activation in the murine protein-overload nephropathy (PON) model, induced by the intraperitoneal administration of a large amount of free (non-esterified) fatty acid-conjugated BSA (FFABSA) [21]. PON mice exhibit severe proteinuria without glomerular injury, and exhibit acute tubular injury due to excessive FFA-BSA reabsorption in PTECs [21]. The mechanism underlying kidney injury in PON is closely related to FFA overload rather than to BSA overload. Intracellularly accumulated FFAs exert lipotoxicity (LTx) and cause FFA metabolic dysfunction associated with PPARα loss, inflammation, increased oxidative stress (OS), apoptosis stimulation and severe PTEC injury [4,21]. PPARα deficiency dramatically aggravated LTx and tubular damage in PON, which were reduced by the renal PPARα-activating effect of the PPARα agonist clofibrate [4,22], suggesting that PON is a suitable animal model for analysing the renoprotective effects of PPARα activation. Therefore, PON herein, was used for the evaluation of Irbe’s novel pharmacological renal PPARα activation effects. The most important beneficial effects of renal PPARα activation are increased fatty acid metabolism, which reduces LTx derived from proteinuria. To clarify the renoprotective effects mediated by PPARα in suppressing the initial step of kidney injury in PON, we employed a pretreatment protocol in which Irbe treatment was started before a kidney injury episode.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and experimental design

Male wild-type (WT) mice and Ppara-null (KO) mice (age, 13 weeks; body weight, 24–30 g) were used in the present study. WT and KO mice were on a C57BL6 background, as previously described [23]. All procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of Shinshu University, the National Institutes of Health and the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

Study 1

WT and KO mice were divided into three groups: a control group (vehicle- [0.1% methylcellulose, MC] treated group, n = 10 and n = 6 respectively), Los-treated group (n = 10 and n = 6 respectively) and Irbe-treated group (n = 10 and n=6 respectively) (50 bw/day of each ARB for 14 days). The chemicals were administered via oral gavage. After 14 days, the mice were killed.

Study 2

WT and KO mice were administered a daily intra-peritoneal bolus injection of 0.3 g of FFA-BSA in sterile saline for 4 days, and the dose was increased (0.35 g for 3 days and 0.4 g for 7 days) to induce PON [21,22]. The following WT and KO mice groups were used: vehicle- (0.1% MC) treated mice without PON (Con, n = 10 and n = 6 respectively), vehicle-treated mice with PON (Veh-PON, n = 6 and n = 6 respectively), Los-treated mice with PON (Los-PON, n = 6 and n = 6 respectively), Irbe-treated mice with PON (Irbe-PON, n = 6 and n = 6 respectively), and Irbe and MK886 (PPARα antagonist)-treated mice with PON (Irbe-MKPON, n = 6, WT only). The vehicle or respective ARB (50 mg/kg bw/day) and PPARα antagonist (MK886, 1 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) were administered every day from Day 1 to Day 20. BSA was injected intraperitoneally every day from Day 7 to Day 20. All groups of WT mice were killed at Day 20. The procedures related to the preliminary experiments for the determination of the appropriate doses of Irbe and Los, as well as to the effect of MK886 on blood pressure, are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Details of methods for analyses

Details of analysis methods and miscellaneous methods are described in Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table S1 [24].

Statistical analyses

Significant differences with respect to the interactive effects were analysed using one-way ANOVA, and Tukey test for multiple comparisons, correspondingly. Values represent the mean ± S.D. Probability values less than 0.05 were considered significantly different. Statistical analyses were performed by using the SPSS Statistics version 22.0J (IBM), and Stat Flex version.6 for Windows (ARTECH).

RESULTS

Irbe activates PPARα in kidney tissues

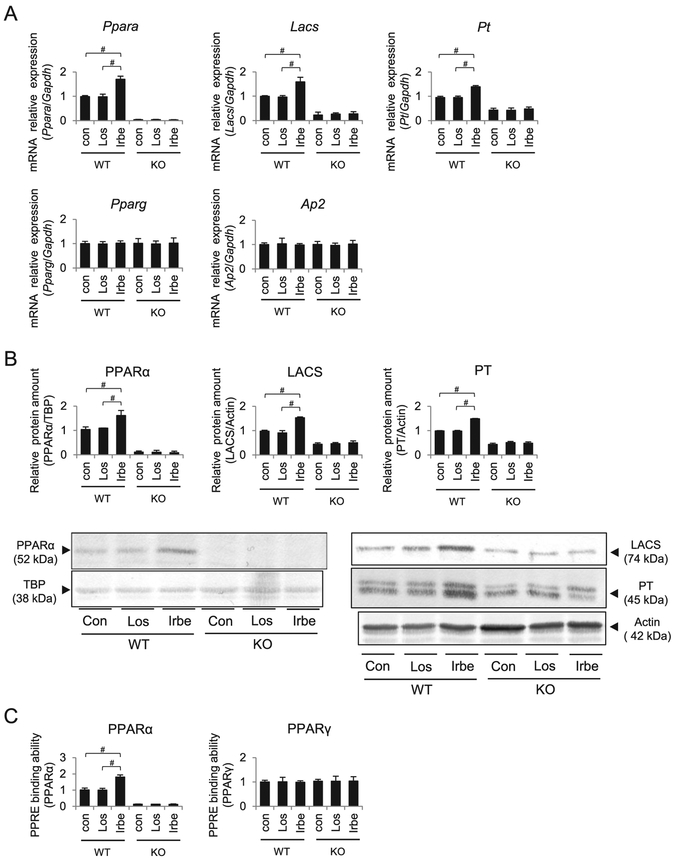

Vehicle, Irbe and losartan (Los; an ARB without PPARα agonist activity) were administered to WT and Ppara-null (KO) mice, and their effects were compared. The expression of Ppara mRNA, PPARα protein, PPAR response element-(PPRE) binding of intra-nuclear PPARα, and the mRNA expression and protein amount of the representative PPARα target genes encoding long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase (LACS) and peroxisomal thiolase (PT) were significantly increased in the kidneys of Irbe-treated WT mice (Figure 1). No changes in the expression of renal PPARα and its target genes were detected in the kidneys of Los-treated WT mice and in those of all KO mice groups.

Figure 1. PPARα, PPARγ and their target gene expression after each respective treatment in kidneys of WT and Ppara-null (KO) mice.

(A) Expression of mRNAs encoding PPARα, PPARγ and their target genes LACS, PT and AP2. (B) PPARα and its target gene protein (LACS and PT) levels. (C) PPRE binding ability of PPARα and PPARγ in each group. Con, control; Los, losartan; Irbe, irbesartan. Values represent the mean ± S.D. (n = 10 for WT; n = 6 for KO). We compared the data among treatment each genotype by using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test. Significant differences are indicated with #P < 0.05.

Since Irbe activates PPARγ, another PPAR subtype, PPARγ expression was also determined, and no changes in Pparg mRNA and PPRE binding ability of PPARγ and a representative PPARγ target gene, adipocyte fatty acid binding protein 2 (AP2), were detected in the kidneys of all mice groups.

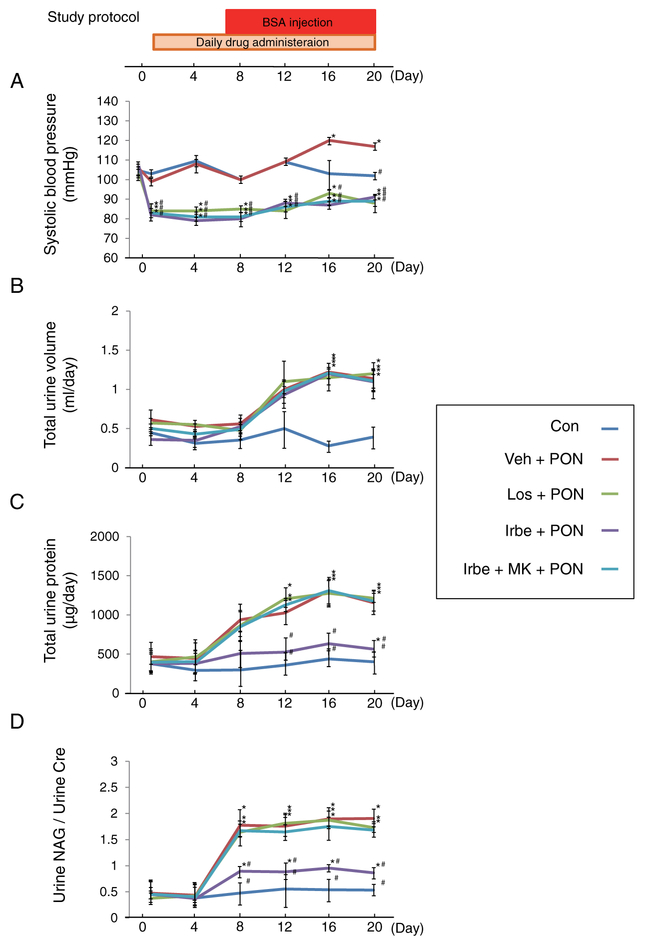

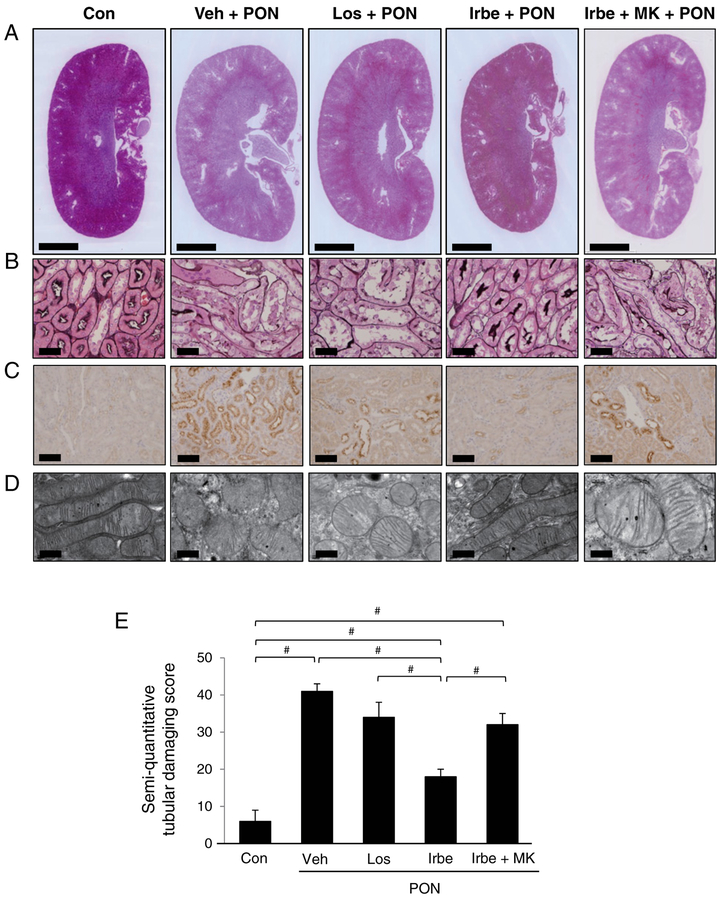

Irbe treatment exerts renoprotective effects in PON-WT mice

The renoprotective effects of Irbe were evaluated in the PON model using WT mice. None of the mice died during the experimental period. The systemic alterations were compared among the five treatment groups (Figure 2). The systolic blood pressure in the Veh-PON group increased from Day 16 (Figure 2A), whereas the systolic blood pressure in all ARB-PON groups rapidly decreased after administration of the respective ARB. These hypotensive effects were observed during the entire experimental period, and were identical among the groups. The urine volumes were significantly and identically increased from Day 16 in all PON groups (Figure 2B). The urine protein excretion and urine N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase (NAG)/urine creatinine (Cr) ratio were greatly and identically increased in the Veh-PON, Los-PON and Irbe-MK-PON groups. On the other hand, those in the Irbe-PON group were significantly attenuated and were maintained at levels similar to those of the Con group (Figures 2C and 2D). Kidney sections revealed extensive swelling of the renal cortices in the Veh-PON, Los-PON and Irbe-MK-PON groups, whereas the renal cortices in the Irbe-PON group appeared normal (Figure 3A). Light microscopic analysis showed tubular injury consisting of tubular dilation and sloughing of PTECs in the Veh-PON, Los-PON and Irbe-MK-PON groups, whereas these injuries in the Irbe-PON group were markedly attenuated (Figure 3B). Immunohistochemical analysis showed strong positive staining for osteopontin, a pathological marker of tubular injury, in PTECs in the Veh-PON, Los-PON and Irbe-MK-PON groups, whereas only slightly positive staining was observed in the Irbe-PON group (Figure 3C). Electron microscopic analysis revealed morphological changes of the mitochondria, i.e. swelling and rupture, in PTECs in the Veh-PON, Los-PON and Irbe-MK-PON groups; such changes were scarcely detected in the Irbe-PON group (Figure 3D). A semi-quantitative scoring analysis demonstrated that the severity of tubular injury in the Irbe-PON group was significantly attenuated (Figure 3E). Pathological analyses also revealed glomerular swelling in all of the PON groups; however, other glomerular lesions including podocyte damage were not detected in all of the PON groups (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 2. The study protocol of PON and the alterations in the systemic parameters in each group of WT mice with PON.

(A) Systolic blood pressure, (B) total urine volume, (C) total urine protein and (D) ratio of urine NAG/urine Cr in each group are indicated. MK, MK886. Significant differences compared with Day 0 in each group using Tukey’s test, are indicated with *P < 0.05; significant differences compared with the Veh-PON group by using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test are indicated with #P < 0.05. Values represent the mean ± S.D. (n=10 for Con; n=6 for treatment groups).

Figure 3. Pathological findings in each group of WT mice with PON.

(A) Low-magnification histological photographs of kidney sections stained with haematoxylin and eosin. Scale bar 2 mm. (B) Light microscopy analyses of tubular lesions. Kidney sections were stained with periodic acid-methenamine-silver. Scale bar = 50 μm. (C) Immunohistochemical stains for osteopontin. Damaged PTECs were positively stained for osteopontin. Scale bar = 100 μm. (D) Electron micrographs of mitochondria in PTECs. Scale bar = 600 nm. (E) The results of the semi-quantitative tubular damaging score. The scores represent the mean ± S.D. (n=10 for Con; n=6 for treatment groups). Significant differences one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test are indicated with #P < 0.05.

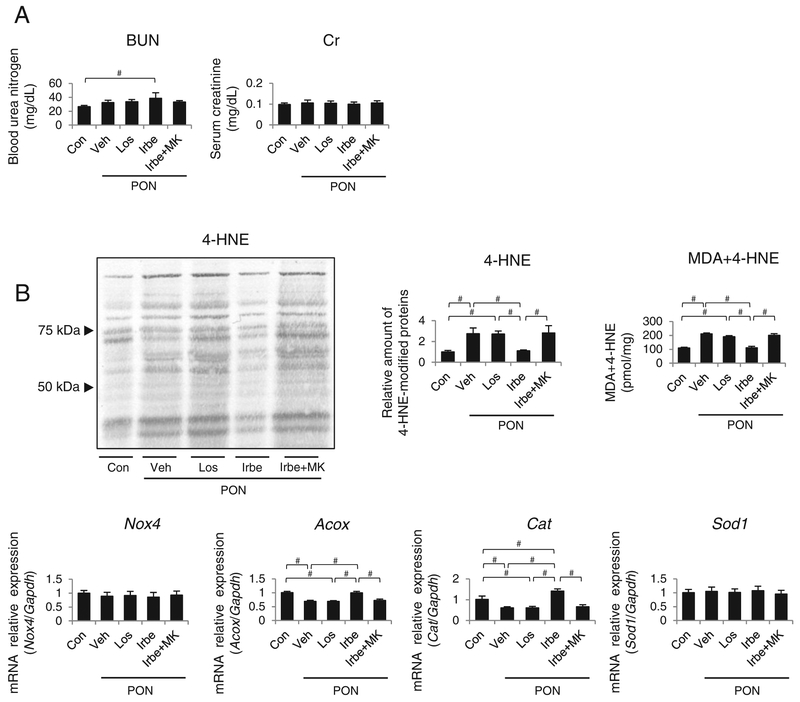

The renoprotective effects of Irbe are associated with improvements in OS, inflammation, apoptosis and FFA metabolism

The level of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) was significantly increased in the Irbe-PON group; however, the serum Cr levels did not differ among the groups (Figure 4A). PON-induced tubular injuries are related to intracellular LTx causing OS, inflammation and apoptosis; therefore, these factors were compared among the five groups. Immunoblot analysis and a colorimetric assay revealed that markers for tissue OS, i.e. renal 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal-(4-HNE) modified proteins and oxidized lipids (malondialdehyde [MDA] + 4-HNE) were significantly and identically increased in the Veh-PON, Los-PON and Irbe-MK-PON groups, whereas they were attenuated in the Irbe-PON group (Figure 4B). The expression of mRNA encoding the reactive oxygen species-generating oxidative enzymes nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 4 (Nox4) and acyl-CoA oxidase (ACOX), and that of the antioxidant enzymes catalase (Cat) and Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase (SOD1) was examined. The expression of Nox4 and Sod1 mRNA did not differ among the five groups. Expression of mRNA for Acox and Cat, which are representative PPARα-regulated mo lecules, was significantly decreased in the Veh-PON, Los-PON and Irbe-MK-PON groups. In the Irbe-PON group, Acox mRNA levels were similar to that of the Con group, whereas that of Cat mRNA was significantly increased compared with that of the Con group.

Figure 4. The alterations in the renal function and OS markers in kidney tissues of each group of WT mice with PON.

(A) Serum levels of BUN and serum Cr in each group of mice. (B) The alterations in the tissue OS markers (4-HNE-modified proteins), the amount of oxidative lipids (malondialdehyde + 4-HNE), and Nox4, Acox, Cat and Sod1 mRNAs. Values represent the mean ± S.D. (n = 10 for Con; n = 6 for treatment groups). Significant differences by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test are indicated with #P < 0.05.

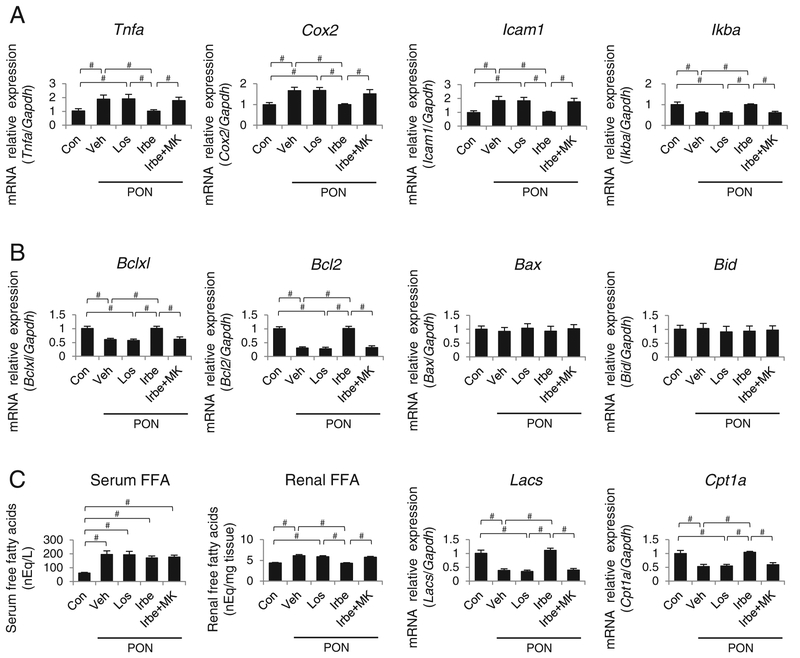

The expression of mRNA encoding pro-inflammatory mediators, tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1) was significantly and identically increased, and the mRNA expression of IκBα, an important PPARα-regulated anti-inflammatory molecule, was decreased in the Veh-PON, Los-PON and Irbe-MK-PON groups (Figure 5A). In contrast, the expression of mRNAs encoding respective proteins in the Irbe-PON group was similar to that in the Con group.

Figure 5. The alterations in the pro-inflammatory mediators, apoptosis-related molecules and FFA metabolism in the kidney tissues of each group of WT mice with PON.

(A) Tnfa, Cox2, Icam1 and Ikba mRNA levels. (B) Bclxl, Bcl2, Bax and Bid mRNA levels. (C) Serum and renal FFA content, and Lacs and Cpt1a mRNA levels. Values represent the mean ± S.D. (n = 10 for Con; n = 6 for treatment groups). Significant differences by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test are indicated with #P=< 0.05.

The expression of Bclxl and Bcl2 mRNA transcripts, which encode two anti-apoptotic, PPARα-regulated molecules controlling mitochondrial permeability, was significantly decreased in the Veh-PON, Los-PON and Irbe-MK-PON groups, whereas Bclxl and Bcl2 expression in the Irbe-PON group was identical with that in the Con group (Figure 5B). The expression of Bax and Bid mRNAs, encoding two apoptosis-stimulating molecules, did not differ among the five groups.

To assess LTx, changes in the renal FFA levels were analysed. The FFA serum levels were dramatically increased by PON, but did not differ among the PON groups, suggesting an identical renal FFA overload in all PON groups (Figure 5C). The renal tissue FFA content was greatly increased, and the expression of mRNA encoding LACS and carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1α (CPT1α), which are two important PPARα-regulated fatty acid metabolic enzymes, was significantly decreased in the Veh-PON, Los-PON and Irbe-MK-PON groups. However, the mRNA expression of LACS and CPT1α in the Irbe-PON group was similar to those in the Con group.

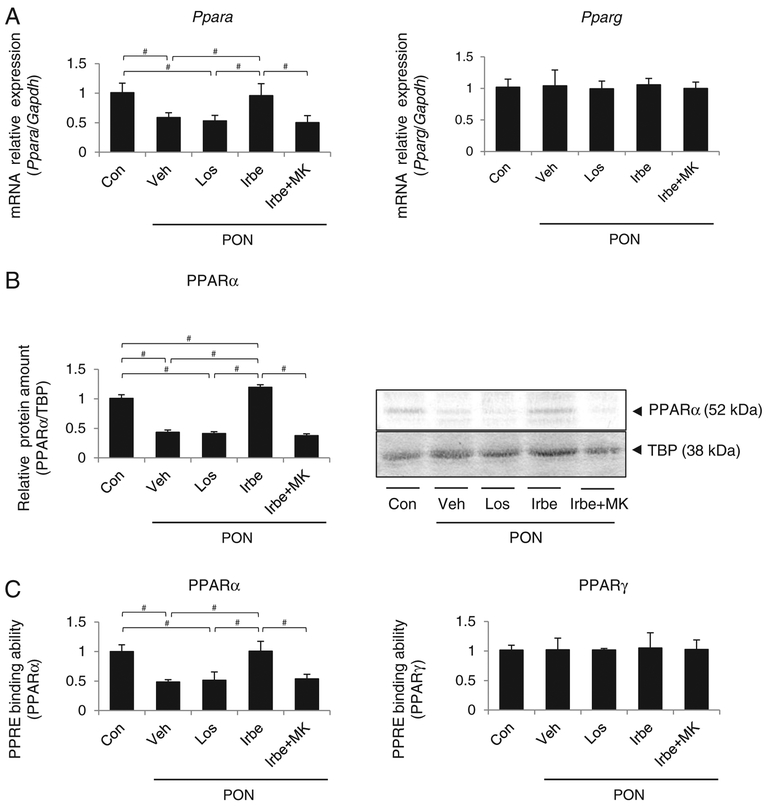

The mRNA expression, amount of intra-nuclear protein and PPRE binding ability of PPARα were significantly decreased in the kidney tissues of the Veh-PON, Los-PON and Irbe-MK-PON groups, but in the Irbe-PON group, they were maintained equal to or increased beyond the levels in the Con group (Figure 6). PPARγ expression did not differ among the five groups.

Figure 6. PPARα and PPARγ expression in kidney tissues of each group of WT mice with PON.

(A) Ppara and Pparg mRNA levels. (B) Intra-nuclear PPARα protein expression. (C) PPRE binding ability of PPARα and PPARγ in each group. Values represent the mean ± S.D. (n = 10 for Con; n = 6 for treatment groups). Significant differences by one-way ANOV6A and Tukey’s test are indicated with #P=< 0.05.

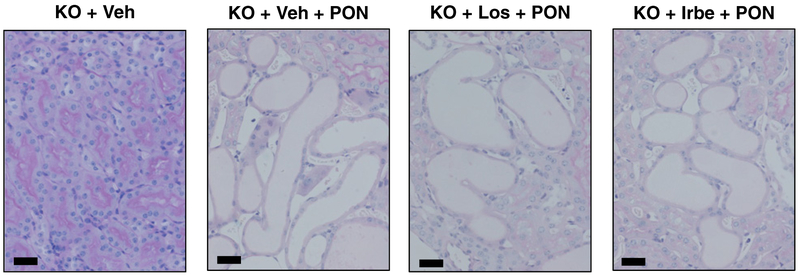

Renoprotective effects of Irbe are not detected in PON-KO mice

We investigated the renoprotective effects of ARBs in PON-KO mice. Previous studies demonstrated that KO mice are highly sensitive to PON, and that PON-KO mice generally exhibit severe kidney injury and high mortality [4]. As previously reported, almost all PON-KO mice in the present study died, irrespective of ARB treatment for severe kidney injury, within 7 days. The mortality was identical among PON-KO groups. The representative pathological findings of PON-KO mice on Day 4 are shown in Figure 7. Severe tubular injury is observed in KO + Veh + PON, KO + Los + PON and KO + Irbe + PON mice. None of the renoprotective effects of Irbe were detected in PON-KO mice.

Figure 7. Pathological findings in each group of Ppara-null (KO) mice with PON.

Low-magnification histological photographs of the tubular area stained with periodic acid Schiff (PAS). Scale bar=50 μm (KO + Veh, vehicle-treated Ppara-null mice; KO + Veh + PON, vehicle-treated Ppara-null mice with PON; KO + Los + PON, Los-treated Ppara-null mice with PON, KO + Irbe + PON, Irbe-treated Ppara-null mice with PON.

DISCUSSION

The current study revealed that Irbe treatment increased expression of PPARα and PPARα signalling in kidney tissue. Because these changes were not detected in the kidneys of KO mice, these were most likely related to PPARα activation. Los treatment did not activate PPARα and thus activation of PPARα by Irbe was Irbe-specific rather than due to the suppression of RAS, a common ARB class effect. Furthermore, the present results suggest that Irbe exerts its renoprotective effects through renal PPARα activation, maintaining fatty acid metabolic homoeostasis along with anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects as well as decreased tubular injuries. The reversion of Irbe-mediated renal protection by PPARα antagonists and the insufficient renoprotective effect in KO mice strongly supports a PPARα-mediated mechanism for the renoprotective effects of Irbe treatment. These effects were consistent with those found in previous studies using fibrates [22,25,26]. Since fibrates may exert nephrotoxicity that exceeds their renoprotective effects in kidney dysfunction, Irbe treatment may be a safer alternative [22].

Proteinuria causes tubulointerstitial injuries (TI) and is an important common risk factor for CKD progression [4,27,28]. Furthermore, renal prognosis is closely correlated to the degree of TI [29]. The mechanism underlying proteinuric toxicity is controversial, but several studies showed the importance of FFAs [4]. The large amount of FFAs bound to albumin, filtered through damaged glomeruli, is linked to increased absorption of FFAs by PTECs beyond metabolic capacity. As a result, the increase in un-metabolized intracellular FFAs causes LTx and TI [4]. A decrease in FFA metabolism associated with reduced PPARα expression was one of the most important risk factors causing TI and CKD progression [6]. Therefore, drugs maintaining renal PPARα levels, such as Irbe, may protect against TI and suppress the progression of CKD.

The current study suggests that Irbe treatment has anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative and anti-apoptosis effects; these effects have previously been reported [30–37]. Experimental and clinical studies showed Irbe treatment-induced suppression of kidney inflammation, and reduced serum levels of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), TNFα and interleukin-6 (IL-6) [30–32]. Irbe treatment increased the expression of anti-oxidative enzymes SOD1, glutathione peroxidase and Cat, and decreased serum oxidative markers, such as reactive oxygen species and MDA in a rat model and patients with hypertension or DM [33–35]. Moreover, Irbe treatment suppressed PTEC apoptosis caused by protein overload or contrast agents [36,37]. These pharmacological effects of Irbe may be associated with PPAR activation.

RAS activation causes hypertension and kidney injuries, and increases the expression of inflammatory mediators and OS [38–40]. Hypertension induces apoptosis in multiple organs including the kidneys [41]. RAS activation occurs in PON and aggravates proteinuria and TI, and RAS inhibition by ARB had renoprotective effects against PON [42,43]. In the current study, however, no significant attenuation of TI was observed in the Los-PON group. Since the BSA injection period was longer and the BSA dose was higher than those in previous studies, these severe experimental conditions might have concealed the protective effects of RAS inhibition. Nevertheless, Irbe treatment exerted renoprotective effects under these conditions. Several reports have indicated an interesting relationship between RAS and PPARα: a decrease in renal PPARα causes RAS activation, inflammation and OS, which are attenuated by PPARα activation [44,45]. These findings suggest that PPARα activation enhances the renoprotective effects of RAS inhibition. Therefore, Irbe treatment may attenuate the severe PON-induced TI by a dual effect of RAS inhibition and PPARα activation.

The current study suggests that Irbe treatment exerts a strong anti-proteinuric effect against PON. In the PON model, a relatively large amount of overloaded BSA, i.e. exceeding the reabsorption ability of PTECs, is filtered from non-damaged glomeruli (Supplementary Figure S1). Since the mechanism underlying glomerular protein filtration in PON is only marginally dependent on the intraglomerular pressure, the glomerular protective effects and blood pressure-lowering effects of ARBs do not significantly affect the large amount of urine protein. Both the Veh-PON and Los-PON groups exhibited severe TI after BSA-induced LTx. Therefore, the BSA tubular reabsorption capacity was strongly impaired in these treatment groups, resulting in equally high proteinuric levels. On the other hand, tubular damage was only mildly present in the Irbe-PON group with preservation of the BSA tubular reabsorption capacity, which was reflected by decreased urinary protein levels in this treatment group.

Interestingly, levels of BUN were significantly higher in the Irbe-PON group. Because the increase in BUN levels was not related to the other kidney injury markers in the Irbe-PON group, we postulated that the increased BUN levels did not reflect kidney injury. We thus hypothesize that the mechanism underlying the increased BUN levels in the Irbe-PON group is as follows: Irbe activates renal PPARα and increases FFA metabolic ability, resulting in the maintenance of energy homoeostasis and reabsorption capacity of the PTECs. As a result, the reabsorption and catabolism of overloaded BSA were increased in the Irbe-PON group as detected by the increase in serum protein and BUN. Indeed, serum albumin and the total protein level were increased in Irbe-PON group (Supplementary Table S2), supporting our hypothesis. We considered that BUN is not a suitable marker for evaluating kidney function in the PON model, and other kidney injury markers should be included in future studies using this model.

In the current study, Irbe treatment might have activated systemic PPARα and PPARγ, which are known to improve fatty acid metabolism, insulin tolerance and glucose metabolism [11–17]. It is possible that the resulting systemic metabolic improvement could have indirect renoprotective effects. In particular, these effects might decrease the degree of renal FFA overload in the Irbe-PON group, although significant reduction in the level of serum FFA was not detected in the current study. Furthermore, vascular PPARα and PPARγ have been shown to exert anti-inflammatory and anti-atherosclerotic effects [14,15,46,47], suggesting that Irbe treatment might protect against potential PON-induced vascular injuries.

Because renal PPARγ activation has been shown to have renoprotective effects [11–15], it is important to consider the possibility of renal PPARγ activation by Irbe treatment. In the current study, increased mRNA expression and PPRE binding ability of PPARγ in the Irbe-treated WT group were not detected. Moreover, if Irbe had a significant renoprotective effect via PPARγ activation, we would have detected this in the Irbe-MK-PON WT and Irbe-PON-KO group. However, we could not find any renoprotective effect in these treatment groups. From these results, we concluded that the renoprotective effects were mainly due to PPARα activation rather than PPARγ activation. However, we cannot entirely deny the possibility of undetected renoprotective effects of PPARγ activation. In the present experiments using KO mice, the kidney injury was too severe to evaluate the protective effects of ARBs; therefore, the reno-protective effect of Irbe mediated by PPARγ might have been masked by the severe kidney injury. In addition, given that the expression of PPARγ is much smaller than that of PPARα in kidney tissue, a potential renoprotective effect via PPARγ activation may not be detected. Thus, various undetected effects of Irbe might have contributed to the renoprotective effects in the PON model.

There are several limitations in the present study. First, we used a tail cuff method to measure blood pressure. The tail cuff method generally is associated with wider blood pressure variation than continuous arterial blood pressure monitoring. Therefore, it is possible that we could not detect significant differences in blood pressure among the groups because of measurement variability. However, our preliminary experiments and previous studies demonstrated that the blood pressure-lowering effects of Los and Irbe are identical at the same milligram (mg) dosage (Supplementary Methods). One of the main mechanisms underlying the renoprotective effects of ARBs is the lowering of blood pressure; therefore, the renoprotective effect through blood pressure-lowering is identical between Irbe and Los treatment. On the other hand, the current study demonstrated that Irbe had a stronger renoprotective effect than observed for Los. We conclude that the additional renoprotective effect of Irbe beyond blood pressure-lowering is strongly associated with renal PPARα activation.

Further, we employed a pretreatment protocol in the present study. The main mechanism underlying the renoprotective effect of Irbe is the activation of renal PPARα and the increase in the metabolic capacity of FFA binding to urinary protein. Thus, the mechanism underlying the observed renoprotective effect is the elimination of important tubular toxic factors, i.e. FFAs, thereby preventing overt kidney injury. Therefore, we postulate that the renoprotective effects of Irbe after the development of PON may be attenuated. It is still unknown whether or not PPARα activation by Irbe treatment can improve renal morphology and function after PON is established; however, for the clinical applicability of Irbe treatment, it is important that Irbe successfully attenuates fatty acid toxicity, especially at the early stages of kidney disease.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVES.

Activation of renal PPARα is renoprotective, but there is no safe PPARα activator for patients with CKD. Irbe may activate renal PPARα; however, Irbe’s renal PPARα-activating effects and the role of PPARα signalling in the renoprotective effects of Irbe are unknown.

The current study shows for the first time that Irbe treatment can activate renal PPARα and exert PPARα-dependent reno-protective effects in the murine PON model.

These results suggest potential renoprotective clinical benefit of renal PPARα activation by Irbe in human CKD patients with proteinuria. This safe clinical method for activating renal PPARα may be a novel therapeutic strategy against CKD in future. Irbe may be a promising drug for patients with kidney disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Ms M. Watanabe and Ms T. Nishizawa (Department of pathology, Shinshu University School of Medicine, Japan) for their assistance with the pathological analyses.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co. and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) in Japan [grant number 25460329].

Abbreviations:

- ACOX

acyl-CoA oxidase

- AP2

adipocyte fatty acid binding protein 2

- ARB

angiotensin II receptor blocker

- BUN

blood urea nitrogen

- Cat

catalase

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- COX2

cyclooxygenase 2

- CPT1α

carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1α

- Cr

creatinine

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- FFA

free (non-esterified) fatty acid

- 4-HNE

4-hydroxy-2-nonenal

- ICAM1

intercellular adhesion molecule 1

- Irbe

irbesartan

- Irbe-MK-PON

MK886-treated mice with PON

- Irbe-PON

Irbe-treated mice with PON

- LACS

long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase

- Los

losartan

- Los-PON

Los-treated mice with PON

- LTx

lipotoxicity

- MDA

malondialdehyde

- NAG

N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase

- Nox4

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 4

- OS

oxidative stress

- PON

protein-overload nephropathy

- PPARα

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

- PPRE

PPAR response element

- PT

peroxisomal thiolase

- PTEC

proximal tubular epithelial cell

- RAS

renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system

- SOD1

Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase

- Tel

telmisartan

- TI

tubulointerstitial injuries

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor α

- Veh-PON

vehicle-treated mice with PON

- WT

wild-type

REFERENCES

- 1.Kersten S, Desvergne B and Wahli W (2000) Roles of PPARs in health and disease. Nature 405, 421–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aoyama T, Peters JM, Iritani N, Nakajima T, Furihata K, Hashimoto T and Gonzalez FJ (1998) Altered constitutive expression of fatty acid-metabolizing enzymes in mice lacking the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha). J. Biol. Chem 273, 5678–5684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamijo Y, Hora K, Tanaka N, Usuda N, Kiyosawa K, Nakajima T, Gonzalez FJ and Aoyama T (2002) Identification of functions of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha in proximal tubules. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol 13, 1691–1702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamijo Y, Hora K, Kono K, Takahashi K, Higuchi M, Ehara T, Kiyosawa K, Shigematsu H, Gonzalez FJ and Aoyama T (2007) PPARalpha protects proximal tubular cells from acute fatty acid toxicity. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol 18, 3089–3100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li S, Nagothu KK, Desai V, Lee T, Branham W, Moland C, Megyesi JK, Crew MD and Portilla D (2009) Transgenic expression of proximal tubule peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha in mice confers protection during acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 76, 1049–1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang HM, Ahn SH, Choi P, Ko YA, Han SH, Chinga F, Park AS, Tao J, Sharma K, Pullman J et al. (2015) Defective fatty acid oxidation in renal tubular epithelial cells has a key role in kidney fibrosis development. Nat. Med 21, 37–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schoonjans K, Staels B and Auwerx J (1996) Role of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) in mediating the effects of fibrates and fatty acids on gene expression. J. Lipid Res 37, 907–925 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis TM, Ting R, Best JD, Donoghoe MW, Drury PL, Sullivan DR, Jenkins AJ, O’Connell RL, Whiting MJ, Glasziou PP et al. (2011) Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes Study investigators: effects of fenofibrate on renal function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: the Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes (FIELD) Study. Diabetologia 54, 280–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ansquer JC, Foucher C, Rattier S, Taskinen MR, Steiner G and Investigators, DAIS (2005) Fenofibrate reduces progression to microalbuminuria over 3 years in a placebo-controlled study in type 2 diabetes: results from the Diabetes Atherosclerosis Intervention Study (DAIS). Am. J. Kidney Dis 45, 485–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jun M, Zhu B, Tonelli M, Jardine MJ, Patel A, Neal B, Liyanage T, Keech A, Cass A and Perkovic V (2012) Effects of fibrates in kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 60, 2061–2071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clasen R, Schupp M, Foryst-Ludwig A, Sprang C, Clemenz M, Krikov M, Thöne-Reineke C, Unger T and Kintscher U (2005) PPARgamma-activating angiotensin type-1 receptor blockers induce adiponectin. Hypertension 46, 137–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schupp M, Janke J, Clasen R, Unger T and Kintscher U (2004) Angiotensin type 1 receptor blockers induce peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activity. Circulation 109, 2054–2057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Waki H, Murakami K, Motojima K, Komeda K, Ide T, Kubota N, Terauchi Y, Tobe K et al. (2001) The mechanisms by which both heterozygous peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) deficiency and PPARgamma agonist improve insulin resistance. J. Biol. Chem 276, 41245–41254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marx N, Duez H, Fruchart JC and Staels B (2004) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and atherogenesis: regulators of gene expression in vascular cells. Circ. Res 94, 1168–1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang HC, Ma LJ, Ma J and Fogo AB (2006) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist is protective in podocyte injury-associated sclerosis. Kidney Int. 69, 1756–1764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clemenz M, Frost N, Schupp M, Caron S, Foryst-Ludwig A, Böhm C, Hartge M, Gust R, Staels B, Unger T et al. (2008) Liver-specific peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha target gene regulation by the angiotensin type 1 receptor blocker telmisartan. Diabetes 57, 1405–1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rong X, Li Y, Ebihara K, Zhao M, Kusakabe T, Tomita T, Murray M and Nakao K (2010) Irbesartan treatment up-regulates hepatic expression of PPARalpha and its target genes in obese Koletsky (fa(k)/fa(k)) rats: a link to amelioration of hypertriglyceridaemia. Br. J. Pharmacol 160, 1796–1807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fabiani ME, Dinh DT, Nassis L, Casley DJ and Johnston CI (2000) Comparative in vivo effects of irbesartan and losartan on angiotensin II receptor binding in the rat kidney following oral administration. Clin. Sci. (Lond) 99, 331–341 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parving HH, Lehnert H, Bröchner-Mortensen J, Gomis R, Andersen S, Arner P, Irbesartan in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Microalbuminuria Study Group (2001) The effect of irbesartan on the development of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med 345, 870–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, Berl T, Pohl MA, Lewis JB, Ritz E, Atkins RC, Rohde R, Raz I, Collaborative Study Group (2001) Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med 345, 851–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamijo A, Kimura K, Sugaya T, Yamanouchi M, Hase H, Kaneko T, Hirata Y, Goto A, Fujita T and Omata M (2002) Urinary free fatty acids bound to albumin aggravate tubulointerstitial damage. Kidney Int. 62, 1628–1637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahashi K, Kamijo Y, Hora K, Hashimoto K, Higuchi M, Nakajima T, Ehara T, Shigematsu H, Gonzalez FJ and Aoyama T (2011) Pretreatment by low-dose fibrates protects against acute free fatty acid-induced renal tubule toxicity by counteracting PPARα deterioration. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 252, 237–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akiyama TE, Nicol CJ, Fievet C, Staels B, Ward JM, Auwerx J, Lee SS, Gonzalez FJ and Peters JM (2001) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha regulates lipid homeostasis, but is not associated with obesity: studies with congenic mouse lines. J. Biol. Chem 276, 39088–39093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aoyama T, Yamano S, Waxman DJ, Lapenson DP, Meyer UA, Fischer V, Tyndale R, Inaba T, Kalow W, Gelboin HV et al. (1989) Cytochrome P-450 hPCN3, a novel cytochrome P-450 IIIA gene product that is differentially expressed in adult human liver. cDNA and deduced amino acid sequence and distinct specificities of cDNA-expressed hPCN1 and hPCN3 for the metabolism of steroid hormones and cyclosporine. J. Biol. Chem 264, 10388–10395 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanaka Y, Kume S, Araki S, Isshiki K, Chin-Kanasaki M, Sakaguchi M, Sugimoto T, Koya D, Haneda M, Kashiwagi A et al. (2011) Fenofibrate, a PPARα agonist, has renoprotective effects in mice by enhancing renal lipolysis. Kidney Int. 79, 871–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hashimoto K, Kamijo Y, Nakajima T, Harada M, Higuchi M, Ehara T, Shigematsu H and Aoyama T (2012) PPARα activation protects against anti-Thy1 nephritis by suppressing glomerular NF-κB signaling. PPAR Res. 976089, doi: 10.1155/2012/976089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iseki K, Ikemiya Y, Iseki C and Takishita S (2003) Proteinuria and the risk of developing end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 63, 1468–1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abbate M, Zoja C and Remuzzi G (2006) How does proteinuria cause progressive renal damage? J. Am. Soc. Nephrol 17, 2974–2984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Müller GA, Zeisberg M and Strutz F (2000) The importance of tubulointerstitial damage in progressive renal disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant 15 (Suppl 6), 76–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayashi M, Takeshita K, Uchida Y, Yamamoto K, Kikuchi R, Nakayama T, Nomura E, Cheng XW, Matsushita T, Nakamura S et al. (2014) Angiotensin II receptor blocker ameliorates stress-induced adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance. PLoS One 9, e116163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hartner A, Cordasic N, Klanke B, Menendez-Castro C, Veelken R, Schmieder RE and Hilgers KF (2014) Renal protection by low dose irbesartan in diabetic nephropathy is paralleled by a reduction of inflammation, not of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1842, 558–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ceriello A, Assaloni R, Da Ros R, Maier A, Piconi L, Quagliaro L, Esposito K and Giugliano D (2005) Effect of atorvastatin and irbesartan, alone and in combination, on postprandial endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and inflammation in type 2 diabetic patients. Circulation 111, 2518–2524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anjaneyulu M and Chopra K (2004) Effect of irbesartan on the antioxidant defence system and nitric oxide release in diabetic rat kidney. Am. J. Nephrol 24, 488–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taguchi I, Toyoda S, Takano K, Arikawa T, Kikuchi M, Ogawa M, Abe S, Node K and Inoue T (2013) Irbesartan, an angiotensin receptor blocker, exhibits metabolic, anti-inflammatory and antioxidative effects in patients with high-risk hypertension. Hypertens. Res 36, 608–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiarelli F, Di Marzio D, Santilli F, Mohn A, Blasetti A, Cipollone F, Mezzetti A and Verrotti A (2005) Effects of irbesartan on intracellular antioxidant enzyme expression and activity in adolescents and young adults with early diabetic angiopathy. Diabetes Care 28, 1690–1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Erkan E, De Leon M and Devarajan P (2001) Albumin overload induces apoptosis in LLC-PK(1) cells. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol 280, F1107–F1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiong XL, Jia RH, Yang DP and Ding GH (2006) Irbesartan attenuates contrast media-induced NRK-52E cells apoptosis. Pharmacol. Res 54, 253–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luft FC, Mervaala E, Müller DN, Gross V, Schmidt F, Park JK, Schmitz C, Lippoldt A, Breu V, Dechend R et al. (1999) Hypertension-induced end-organ damage: a new transgenic approach to an old problem. Hypertension 33, 212–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodríguez-Iturbe B, Quiroz Y, Nava M, Bonet L, Chávez M, Herrera-Acosta J, Johnson RJ and Pons HA (2002) Reduction of renal immune cell infiltration results in blood pressure control in genetically hypertensive rats. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol 282, F191–F201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pueyo ME, Gonzalez W, Nicoletti A, Savoie F, Arnal JF and Michel JB (2000) Angiotensin II stimulates endothelial vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 via nuclear factor-kappaB activation induced by intracellular oxidative stress. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 20, 645–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Intengan HD and Schiffrin EL (2001) Vascular remodeling in hypertension: roles of apoptosis, inflammation, and fibrosis. Hypertension 38, 581–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suzuki Y, Lopez-Franco O, Gomez-Garre D, Tejera N, Gomez-Guerrero C, Sugaya T, Bernal R, Blanco J, Ortega L and Egido J (2001) Renal tubulointerstitial damage caused by persistent proteinuria is attenuated in AT1-deficient mice: role of endothelin-1. Am. J. Pathol 159, 1895–1904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Largo R, Gómez-Garre D, Soto K, Marrón B, Blanco J, Gazapo RM, Plaza JJ and Egido J (1999) Angiotensin-converting enzyme is upregulated in the proximal tubules of rats with intense proteinuria. Hypertension 33, 732–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chung S and Park CW (2011) Role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α in diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Metab. J 35, 327–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shin SJ, Lim JH, Chung S, Youn DY, Chung HW, Kim HW, Lee JH, Chang YS and Park CW. (2009) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha activator fenofibrate prevents high-fat diet-induced renal lipotoxicity in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertens. Res 32, 835–845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raspé E, Madsen L, Lefebvre AM, Leitersdorf I, Gelman L, Peinado-Onsurbe J, Dallongeville J, Fruchart JC, Berge R and Staels B (1999) Modulation of rat liver apolipoprotein gene expression and serum lipid levels by tetradecylthioacetic acid (TTA) via PPARalpha activation. J. Lipid Res 40, 2099–2110 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lefebvre P, Chinetti G, Fruchart JC and Staels B (2006) Sorting out the roles of PPAR alpha in energy metabolism and vascular homeostasis. J. Clin. Invest 116, 571–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.