Key Points

Question

What are the long-term outcomes associated with 2 different approaches to administering trastuzumab with neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer?

Findings

Analysis of the ACOSOG Z1041 (Alliance) study of 280 patients revealed no difference in disease-free or overall survival for patients given a regimen of paclitaxel plus trastuzumab followed by fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide plus trastuzumab compared with a regimen of fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel plus trastuzumab.

Meaning

Across a median follow-up of 5 years, no differences were found in disease-free or overall survival between the 2 approaches of administering trastuzumab with neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer.

Abstract

Importance

Pathologic complete response rate (pCR), the primary end point of the ACOSOG (American College of Surgeons Oncology Group) Z1041 (Alliance) trial, and disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) in women with operable HER2-positive breast cancer are similar between treatment regimens.

Objective

To assess DFS and OS for patients treated with sequential vs concurrent anthracycline plus trastuzumab.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Phase 3 randomized clinical trial conducted at 36 centers in the continental United States and Puerto Rico. Women 18 years or older with invasive operable HER2-positive breast cancer were enrolled from September 15, 2007, to December 15, 2011, and randomized to 1 of 2 treatment arms. The analysis data set was locked on October 15, 2017, and analysis was completed on December 15, 2017.

Interventions

Patients randomized to arm 1 received 500 mg/m2 of fluorouracil, 75 mg/m2 of epirubicin, and 500 mg/m2 of cyclophosphamide (FEC) every 3 weeks for 12 weeks followed by the combination of 80 mg/m2 of paclitaxel and 2 mg/kg (except initial dose of 4 mg/kg) of trastuzumab weekly for 12 weeks. Patients randomized to arm 2 received the same combination of paclitaxel with trastuzumab weekly for 12 weeks followed by FEC every 3 weeks with weekly trastuzumab for 12 weeks. Women with hormone receptor–positive disease received endocrine therapy, and radiotherapy was delivered at physician discretion.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcomes were DFS and OS and pCR in the breast and nodes.

Results

Two hundred eighty-two women with HER2-positive breast cancer were enrolled in the trial, and 2 withdrew consent before treatment. Among the remaining 280 women, the median age was 50 years (range, 28-76 years), 232 (82.9%) were white, 29 (10.3%) were black, 8 (2.9%) were Asian, 4 (1.4%) were American Indian or Alaskan Native, and 7 (2.5%) did not report race/ethnicity. There were 22 disease events in arm 1 and 27 in arm 2. Disease-free survival rates did not differ with respect to treatment arm (stratified log-rank P = .96; stratified hazard ratio [HR] [arm 2 to arm 1], 1.02; 95% CI, 0.56-1.83). Overall survival did not differ with respect to treatment arm (stratified log-rank P = .73; stratified HR [arm 2 to arm 1], 1.17; 95% CI, 0.48-2.88).

Conclusions and Relevance

Across a median follow-up of 5.1 years (range, 26 days to 6.2 years), pCR, DFS, and OS did not differ with respect to sequential or concurrent administration of FEC with trastuzumab.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00513292

This phase 3 randomized clinical trial compares disease-free and overall survival among patients with operable HER2-positive breast cancer who received concurrent vs sequential administration of neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Introduction

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy has historically been used for patients with locally advanced breast cancer to downstage the tumor to conserve the breast or convert the disease from inoperable to operable. It also provides a window into the effectiveness of systemic therapies through evaluation of the breast and nodes for pathologic changes. Initially, some clinicians were concerned about disease progression during neoadjuvant therapy; however, few patients have experienced progression during treatment. A meta-analysis of 1928 women receiving anthracycline with or without a taxane for stage I to stage III breast cancer found that the rate of progression during neoadjuvant therapy was 3%.1 Pathologic complete response (pCR) rates with anthracycline and taxane–based chemotherapy have been reported to be 7% to 26%, with differences in pCR rates noted among molecular subtypes.2,3 Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) is a cell-surface receptor involved in the transmission of signals that control cell growth and survival. It is overexpressed in 20% to 30% of breast cancers, and of these, half are positive for estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), or both.4 Overexpression of HER2 is associated with aggressive tumor growth and poor prognosis.4

Among the patients with HER2-positive disease enrolled in the Neoadjuvant Herceptin (NOAH) trial, the addition of trastuzumab to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (consisting of doxorubicin, paclitaxel, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil) improved pCR rates in the breast from 22% to 43% and increased event-free survival (hazard ratio [HR], 0.59; 95% CI, 0.38-0.90).5 The phase 2 TECHNO trial, which evaluated epirubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel and trastuzumab for patients with HER2-positive disease, reported a pCR rate of 39% with a 3-year disease-free survival rate of 77.9%.6 The effectiveness of trastuzumab with chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant setting is evident; however, the cardiac safety of trastuzumab combined with anthracyclines has been questioned.7

The American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z1041 trial for patients with HER2-positive disease was designed to assess whether pCR rates in the breast differed between 2 strategies for administering trastuzumab with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. One strategy was to administer fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide (FEC) followed by paclitaxel and trastuzumab; the second was to administer paclitaxel and trastuzumab followed by FEC and trastuzumab. We previously reported that the pCR rate did not differ significantly between these 2 strategies (56.5% for FEC followed by paclitaxel and trastuzumab vs 54.2% for paclitaxel and trastuzumab followed by FEC and trastuzumab).8 Here we present the disease-free (DFS) and overall survival (OS) in this study population.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

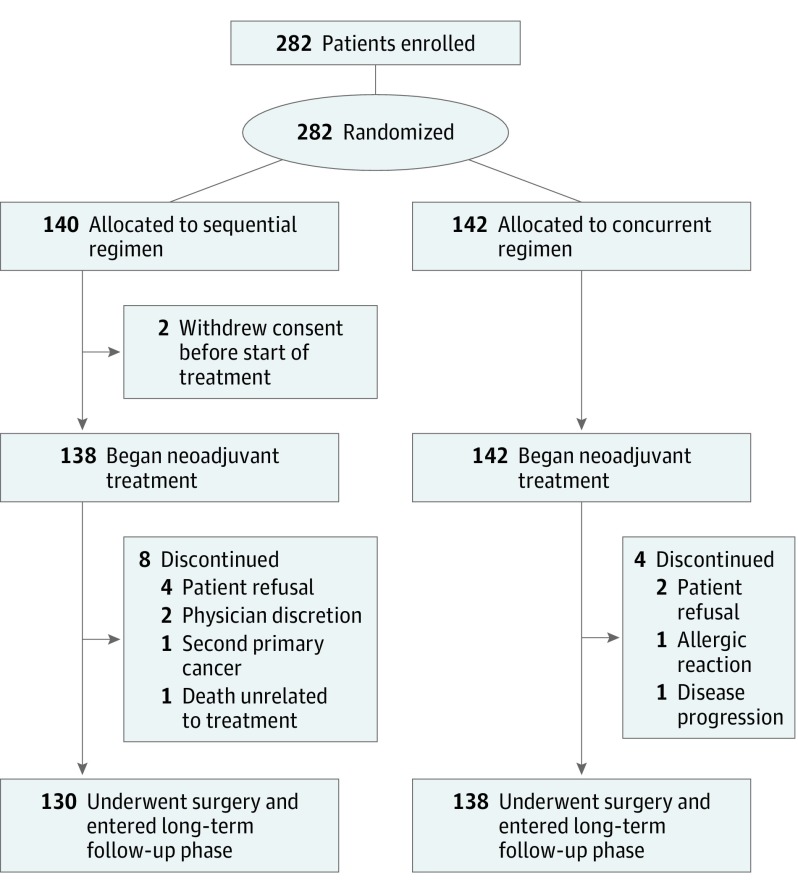

The ACOSOG Z1041 study was a randomized clinical trial that enrolled patients from September 15, 2007, to December 15, 2011, in 36 centers in the continental United States and Puerto Rico. The ACOSOG is now part of the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology. The study enrolled 282 women 18 years or older with invasive HER2-positive breast cancer (either 3+ by immunohistochemistry or amplification by fluorescence in situ hybridization performed in the local laboratory where the patient was treated) who had adequate blood chemistry test results and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 55% or greater (Figure 1). Exclusion criteria were previous breast cancer treatment, neurosensory or neuromotor difficulties, malignant neoplasm within 5 years of breast cancer diagnosis, and history of myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, or cardiomyopathy. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating institutions, and participants provided written informed consent (the full trial protocol is available in Supplement 1).

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram.

Patients were assigned to treatment (1:1) through the Cancer Trials Support Unit’s Oncology Patient Enrollment Network (OPEN) Portal system, using a stratified randomization schema with size of primary tumor, nodal involvement, age, and hormone receptor status as the strata. Patients in arm 1 received 500 mg/m2 of fluorouracil, 75 mg/m2 of epirubicin, and 500 mg/m2 of cyclophosphamide (FEC) on day 1 of a 21-day cycle for 4 cycles, followed by four 21-day cycles of 80 mg/m2 of paclitaxel plus trastuzumab (4 mg/kg initial dose; 2 mg/kg for subsequent doses) on days 1, 8, and 15. Patients in arm 2 received a dose of 80 mg/m2 of paclitaxel plus trastuzumab (4 mg/kg initial dose; 2 mg/kg for subsequent doses) on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 21-day cycle for 4 cycles, followed by four 21-day cycles of FEC on day 1 and 2 mg/kg of trastuzumab on days 1, 8, and 15.

After surgery, patients received 6 mg/kg of trastuzumab every 3 weeks to complete a total of 52 weeks from the first preoperative dose. Radiotherapy was delivered at the discretion of the patient’s medical team. It was recommended in the Z1041 protocol that women with hormone receptor–positive disease receive a minimum of 5 years of endocrine therapy, as is standard practice for patients with hormone receptor–positive disease.

The primary end point of this trial was the proportion of patients who had a pCR in the breast. With a sample size of 256 women (128 per regimen) and a 2-sided significance level of .05, a 2-sample test of binominal proportions would have a 90% chance of detecting a difference of more than 20% in the pCR rate in the breast, assuming the pCR rate with the less effective regimen was no more than 25%. Secondary end points of DFS and OS, along with pathologic response rates in the breast and nodes, were also assessed and are reported herein. For a given treatment arm, the pathologic response rate in the breast and nodes is the percentage of all patients randomized to that treatment arm who began treatment and were found on pathologic examination of the surgical specimen to have no residual disease in the breast or nodes among all the patients randomized to that treatment arm who began treatment. Disease-free survival was defined as the time from randomization to the first of the following events: progression of disease during neoadjuvant therapy; local, regional, or distant recurrence; contralateral breast disease; other second invasive primary cancers; and death from any cause. Analysis was by intention to treat. Data of patients without a disease event were censored at the date of the patient’s last known disease evaluation. Overall survival was defined as the time from randomization to death from any cause or the last date of contact for surviving participants. A stratified log-rank test with the stratum was used to examine whether DFS or OS differed with respect to treatment arm. The strata were age younger than 50 years (yes vs no), hormone-receptor profile (positive for either ER or PR vs negative for both ER and PR), and clinical tumor (T) stage (cT1, 2 vs cT3, 4). The analysis data set was locked on October 15, 2017, yielding a median follow-up time of 5.1 years (range, 26 days to 6.2 years). Data collection and statistical analyses were conducted by the Alliance Statistics and Data Center. Data quality was ensured by review of data by the Alliance Statistics and Data Center and by the study chairperson according to Alliance policies. SAS statistical software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc) was used to analyze the data. This phase 3 therapeutic trial was monitored at least twice annually by the data and safety monitoring committee, a standing committee composed of individuals from within and outside of the Alliance.

Results

From September 15, 2007, to December 15, 2011, 282 women with primary HER2-positive breast cancer were enrolled in the study. Two patients randomized to arm 1 withdrew consent before treatment and were excluded from these analyses. Among the 280 women who began neoadjuvant treatment, the median age was 50 years (range, 28-76 years). Two hundred thirty-two patients (82.9%) were white, 29 (10.3%) were black, 8 (2.9%) were Asian, 4 (1.4%) were American Indian or Alaskan Native, and 7 (2.5 %) did not report their race/ethnicity. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the 280 participants (138 in arm 1 and 142 in arm 2) at study entry were similar between the 2 treatment arms (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Of the 280 patients, 76 (27.1%) had clinical T stage 1 to stage 2, N stage 0 disease, and 112 (40.0%) had ER-negative and PR-negative disease. Eight patients in arm 1 (5.8%) and 4 patients in arm 2 (2.8%) did not undergo a surgical resection for a variety of reasons (eTable 1 in Supplement 2).

In an earlier report of this trial, the pCR rate in the breast was reported to be 56.5% (78 of 138) in arm 1 and 54.2% (77 of 142) in arm 2. Five patients in arm 1 (3.6%) and 6 patients in arm 2 (4.2%) had a pCR in the breast but not in the nodes. Thus, the pCR rate in the breast and nodes was 52.9% in arm 1 (73 of 138 patients; 95% CI, 44.2%-61.5%) and 50% (71 of 142 of patients; 95% CI, 41.5%-58.5%) in arm 2. After surgery, 252 patients (94.0%) were known to have received trastuzumab (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). The administration regimen of adjuvant trastuzumab was modified for 20 patients (10 in arm 1 and 10 in arm 2) owing to cardiac adverse events. Five of these 20 patients also had modifications in the trastuzumab dose in the neoadjuvant setting owing to cardiac adverse events.

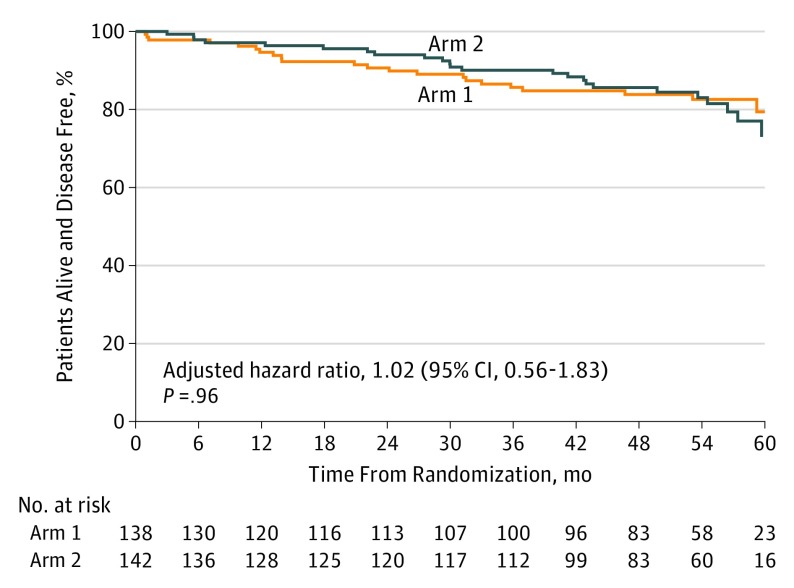

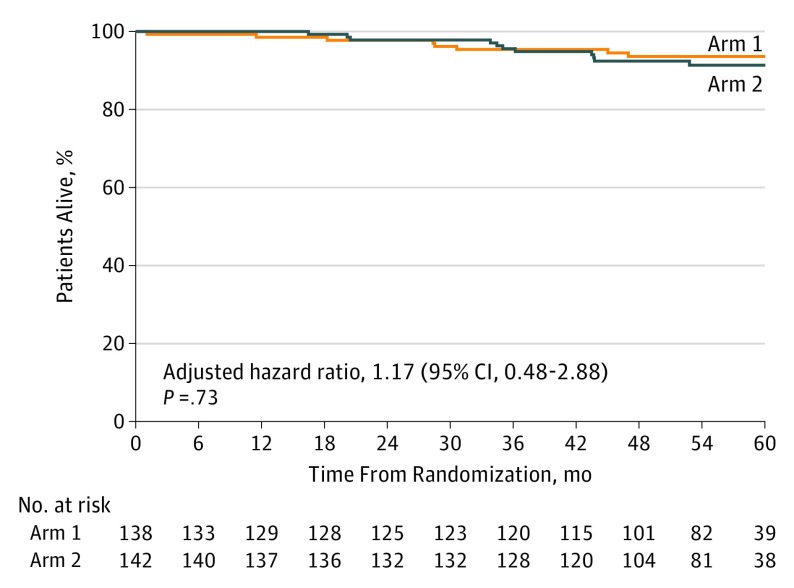

Eighteen recurrences and 2 second primary cancers have been reported among the 138 patients in arm 1, and 22 recurrences and 3 second primary cancers have been reported among the 142 patients in arm 2 (Figure 1; eTables 2 and 3 in Supplement 2). Disease-free survival after randomization did not differ (Figure 2) with respect to treatment arm (stratified log-rank P = .96; stratified HR (arm 2 to arm 1), 1.02; 95% CI, 0.56-1.83). There have been 8 deaths reported in arm 1 and 12 deaths reported in arm 2. The cause of death included this cancer (5 patients in arm 1 and 7 patients in arm 2), drug overdose (1 patient in arm 1), second primary cancer (1 patient in arm 2), respiratory failure (1 patient in arm 2), and unknown (2 patients in arm 1 and 3 patients in arm 2). Overall survival (Figure 3) after registration did not differ between the treatment arms (stratified log-rank P = .73; stratified HR (arm 2 to arm 1), 1.17; 95% CI, 0.48-2.88).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Curves for Disease-Free Survival.

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier Curves for Overall Survival.

Discussion

Based on the findings of a phase 2 study by Buzdar et al9 that the addition of trastuzumab to combination chemotherapy significantly increases pCR rates among women with operable HER2-positive breast cancer, we conducted this phase 3 clinical trial to assess whether the breast pCR differs between 2 approaches to combining trastuzumab with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. A previous publication of this study’s primary analysis reported that breast pCR in patients treated with paclitaxel and trastuzumab followed by FEC and trastuzumab did not differ significantly from that of patients receiving FEC followed by paclitaxel and trastuzumab.8 We now report the findings concerning the secondary outcomes, that is, with a median follow-up of approximately 5 years, DFS is similar among the 2 treatment arms. This further supports the earlier findings that paclitaxel and trastuzumab followed by FEC plus trastuzumab does not result in additional clinical benefit over that of FEC followed by paclitaxel and trastuzumab.

In a large randomized adjuvant clinical trial comparing an anthracycline-based regimen in combination with trastuzumab with a non–anthracycline-based regimen in combination with trastuzumab,10 no significant differences in efficacy were found, but there was a higher rate of cardiac dysfunction in patients receiving the anthracycline-based regimen.10 A joint analysis of 3 adjuvant clinical trials for women with high-risk HER2-negative disease reported that treatment with docetaxel and cyclophosphamide was associated with inferior DFS compared with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide combined with a taxane.11 For women with low-risk HER2-positive breast cancer, a multicenter study of adjuvant paclitaxel with trastuzumab showed a reduction in the risk of early recurrence compared with historical data.12

These studies, along with data from the Z1041 trial, demonstrate that anti-HER2 therapy in combination with cytotoxic agents, many of which regimens have become standard of care, changes the natural history of HER2-positive breast cancer. In this phase 3 clinical trial, taxane and anthracycline in combination with trastuzumab administered neoadjuvantly resulted in a rate of pCR in the breast of approximately 50% of patients. Patients experiencing pCR after neoadjuvant therapy have been shown to have a lower risk of recurrence and death due to breast cancer.13 As a result, close to 50% of patients may not benefit from other treatments, including additional anti-HER2 therapies and surgery. Studies are currently under way to determine whether surgery can be eliminated from the treatment strategy for this subset of patients.14,15,16

Various combinations of trastuzumab and chemotherapy drugs have demonstrated their therapeutic efficacy and safety; however, the optimal combination(s) of these therapies remains to be defined. With the availability of additional anti-HER2 therapies, including lapatinib, pertuzumab, and ado-trastuzumab emtansine and neratinib, the management of HER2-positive disease is evolving. A large phase 3 adjuvant therapy trial of HER2-positive breast cancer found, at a median follow-up of 4 years, a significant reduction in the risk of recurrence with the addition of pertuzumab to trastuzumab and standard chemotherapy.17 In another randomized clinical trial of adjuvant therapy,18 patients with HER2-positive breast cancer who completed chemotherapy with trastuzumab were randomized to 12 months of neratinib or placebo. At 2-year follow-up, the additional 12 months of neratinib therapy significantly reduced the risk of recurrence; however, this treatment was associated with additional adverse effects, and a longer follow-up will be needed to assess its effect on survival. Neoadjuvant administration of more than 1 anti-HER2 agent (trastuzumab and lapatinib) in combination with chemotherapy improved pCR rates, but with no consistent improvement in DFS and OS.19,20 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines version 1.2018 listed the following as the preferred neoadjuvant regimens for HER2-positive breast cancer: (1) doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel plus trastuzumab, with or without pertuzumab, or (2) docetaxel and carboplatin/trastuzumab with or without pertuzumab.21 The current approach of combining multiple anti-HER2 agents is associated with a modest increase in clinical benefit at a substantial added cost and increased treatment-related adverse effects. We need better molecular studies, imaging studies, or both to identify patients whose disease may be controlled with either combination biological agent therapies or better-tolerated combinations of biological and chemotherapeutic agents. Moreover, there is preclinical and clinical evidence of bidirectional crosstalk between the HER2 and ER pathways. In a number of neoadjuvant trials enrolling patients with HER2-positive breast cancer, pCR rates were lower among those with ER-positive and HER2-positive breast cancer than among those with ER-negative and HER2-positive breast cancer, suggesting that simultaneously blocking both HER2 and ER signaling pathways may be a promising strategy for patients with ER-positive and HER2-positive disease.22

Another approach being evaluated is to offer additional therapy with different anti-HER2 agents to patients who have residual disease after neoadjuvant therapy, sparing those patients who experience pCR and are at low risk of recurrence from additional morbidity. The ongoing KATHERINE (A Study of Trastuzumab Emtansine vs Trastuzumab as Adjuvant Therapy in Patients With HER2-Positive Breast Cancer Who Have Residual Tumor in the Breast or Axillary Lymph Nodes Following Preoperative Therapy) trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01772472) is a randomized clinical trial comparing the efficacy and safety of trastuzumab emtansine vs trastuzumab as adjuvant therapy for patients with HER2-positive breast cancer who have residual tumor in the breast or axillary lymph nodes after neoadjuvant therapy.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, this report presents analyses of secondary end points. The sample size was chosen to address the primary aim of the study, not to detect whether the HR for disease progression or death exceeds a prespecified value. However, point and interval estimates for the hazard of disease progression and death are provided to draw conclusions as to whether concurrent administration of trastuzumab with FEC is clinically warranted. Second, during the conduct of this trial, several anti-HER2 agents (pertuzumab, neratinib, ado-trastuzumab emtansine and lapatinib) were approved for patients with HER2-positive disease. Evaluation of the appropriate use of these new agents in patients with operable HER2-positive disease is ongoing.

Conclusions

An earlier report of the results of the Z1041 phase 3 trial compared the pCR of patients with HER2-positive breast cancer treated with FEC followed by paclitaxel and trastuzumab with that of patients treated with paclitaxel and trastuzumab followed by FEC and trastuzumab. Pathologic complete response rates did not differ with respect to concurrent or sequential administration of trastuzumab with FEC. Herein we report, with a median follow-up of 5.1 years, that the DFS and OS also did not differ with respect to concurrent or sequential administration of trastuzumab with FEC. Therefore, concurrent administration of trastuzumab with FEC was not found to offer additional clinical benefit and is not warranted.

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Patient and Tumor Characteristics

eTable 2. Disease Events

eTable 3. Sites of Distant Disease Recurrence and Second Primaries

References

- 1.Caudle AS, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Hunt KK, et al. Impact of progression during neoadjuvant chemotherapy on surgical management of breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(4):932-938. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1390-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cain H, Macpherson IR, Beresford M, Pinder SE, Pong J, Dixon JM. Neoadjuvant therapy in early breast cancer: treatment considerations and common debates in practice. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2017;29(10):642-652. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2017.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaufmann M, von Minckwitz G, Rody A. Preoperative (neoadjuvant) systemic treatment of breast cancer. Breast. 2005;14(6):576-581. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2005.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubin I, Yarden Y. The basic biology of HER2. Ann Oncol. 2001;12(suppl 1):S3-S8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/12.suppl_1.S3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loibl S, von Minckwitz G, Raab G, et al. Surgical procedures after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in operable breast cancer: results of the GEPARDUO trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13(11):1434-1442. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9011-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gianni L, Eiermann W, Semiglazov V, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with trastuzumab followed by adjuvant trastuzumab versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone, in patients with HER2-positive locally advanced breast cancer (the NOAH trial): a randomised controlled superiority trial with a parallel HER2-negative cohort. Lancet. 2010;375(9712):377-384. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61964-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rochette L, Guenancia C, Gudjoncik A, et al. Anthracyclines/trastuzumab: new aspects of cardiotoxicity and molecular mechanisms. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2015;36(6):326-348. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2015.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buzdar AU, Suman VJ, Meric-Bernstam F, et al. ; American College of Surgeons Oncology Group investigators . Fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide (FEC-75) followed by paclitaxel plus trastuzumab versus paclitaxel plus trastuzumab followed by FEC-75 plus trastuzumab as neoadjuvant treatment for patients with HER2-positive breast cancer (Z1041): a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(13):1317-1325. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70502-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buzdar AU, Ibrahim NK, Francis D, et al. Significantly higher pathologic complete remission rate after neoadjuvant therapy with trastuzumab, paclitaxel, and epirubicin chemotherapy: results of a randomized trial in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive operable breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(16):3676-3685. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slamon D, Eiermann W, Robert N, et al. ; Breast Cancer International Research Group . Adjuvant trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(14):1273-1283. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blum JL, Flynn PJ, Yothers G, et al. Anthracyclines in early breast cancer: the ABC Trials-USOR 06-090, NSABP B-46-I/USOR 07132, and NSABP B-49 (NRG Oncology). J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(23):2647-2655. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.4147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tolaney SM, Barry WT, Dang CT, et al. Adjuvant paclitaxel and trastuzumab for node-negative, HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(2):134-141. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cortazar P, Zhang L, Untch M, et al. Pathological complete response and long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer: the CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet. 2014;384(9938):164-172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62422-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carey LA, Berry DA, Cirrincione CT, et al. Molecular heterogeneity and response to neoadjuvant human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 targeting in CALGB 40601, a randomized phase III trial of paclitaxel plus trastuzumab with or without lapatinib. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):542-549. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuerer HM, Krishnamurthy S, Rauch GM, Yang WT, Smith BD, Valero V. Optimal selection of breast cancer patients for elimination of surgery following neoadjuvant systemic therapy [published online October 23, 2017]. Ann Surg. 2017. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lesurf R, Griffith OL, Griffith M, et al. Genomic characterization of HER2-positive breast cancer and response to neoadjuvant trastuzumab and chemotherapy-results from the ACOSOG Z1041 (Alliance) trial. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(5):1070-1077. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Minckwitz G, Procter M, de Azambuja E, et al. ; APHINITY Steering Committee and Investigators . Adjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in early HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(2):122-131. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1703643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan A, Delaloge S, Holmes FA, et al. ; ExteNET Study Group . Neratinib after trastuzumab-based adjuvant therapy in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer (ExteNET): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(3):367-377. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00551-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Azambuja E, Holmes AP, Piccart-Gebhart M, et al. Lapatinib with trastuzumab for HER2-positive early breast cancer (NeoALTTO): survival outcomes of a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial and their association with pathological complete response. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(10):1137-1146. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70320-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Untch M, Loibl S, Bischoff J, et al. ; German Breast Group (GBG); Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynäkologische Onkologie-Breast (AGO-B) Study Group . Lapatinib versus trastuzumab in combination with neoadjuvant anthracycline-taxane-based chemotherapy (GeparQuinto, GBG 44): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(2):135-144. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70397-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN guidelines. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx#site. Accessed May 22, 2018.

- 22.Lousberg L, Collignon J, Jerusalem G. Resistance to therapy in estrogen receptor positive and human epidermal growth factor 2 positive breast cancers: progress with latest therapeutic strategies. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2016;8(6):429-449. doi: 10.1177/1758834016665077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Patient and Tumor Characteristics

eTable 2. Disease Events

eTable 3. Sites of Distant Disease Recurrence and Second Primaries