Abstract

The cytotoxic lymphomas of the skin constitute a heterogeneous group of rare lymphoproliferative diseases that are derived from mature T cells and natural killer (NK) cells that express cytotoxic molecules (T-cell intracellular antigen-1, granzyme A/B, and perforin). Although frequently characterized by an aggressive course and poor prognosis, these diseases can have variable clinical behavior. This review delivers up-to-date information about the clinical presentation, histopathologic features, differential diagnosis, and therapy of extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type, primary cutaneous gamma delta T-cell lymphoma, and primary cutaneous CD8+ aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma.

Occasionally patients present with natural killer (NK)/T or T-cell lymphomas compartmentalized within the skin, which are clinically distinct from mycosis fungoides (MF) and the CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders, and which generally share the discerning characteristic immunomorphologic features of a high-grade process with a cytotoxic phenotype. This group of lymphomas is derived from mature T cells and NK cells that express cytotoxic molecules (T-cell intracellular antigen (TIA)-1, granzyme A/B, and perforin). Patients with these diseases typically undergo an aggressive course with poor outcome, with reported exceptions. The World Health Organization (WHO)/European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) classification of primary cutaneous lymphoma currently categorizes primary cutaneous gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma (PCGDTCL) as a definitive entity and primary cutaneous CD8+ aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma (PCAE-TCL) as a provisional entity within the arm of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.1,2 NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type is considered separately from the cutaneous T-cell lymphomas; we include this entity here, as it sometimes falls within the diagnostic spectrum of specifically cytotoxic hematolymphoid neoplasms arising solely in the skin.

Importantly, MF,3 CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders such as primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, and subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL)1 may express cytotoxic markers. By convention, these otherwise welldefined clinicopathologic entities are not considered within the rubric of the cytotoxic lymphomas.

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma (ENKTL) is a well-defined cytotoxic lymphoma that has a strong association with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection. It is more common in Asia and Central and South America1 than in Europe and North America, accounting for 5%−10% of all non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma cases in the former geographic regions versus 2% in the latter.4 ENKTL commonly affects the nasopharynx and upper aerodigestive tract, with the skin and subcutaneous tissue being the most common sites of secondary spread.5 Approximately 10% of ENKTL cases manifest as primary cutaneous disease.6 Both primary and secondary skin disease show aggressive clinical behavior, with most patients dying within a few months of diagnosis.7–9 Extracutaneous involvement predicts an even poorer outcome (median survival of 4 months compared to 27 months in patients with only skin lesions).7 Additional poor prognostic factors are extranasal location, disease stage, performance status, number of extranodal involved sites,10,11 and EBV viral load in tumor tissues.12

The term “ENKTL nasal type” was adopted by WHO in 200113 and was later included in the WHO/EORTC classification of cutaneous lymphomas.1 In most cases, the tumor cells have an NK-cell phenotype, although a cytotoxic T-cell phenotype can be found of either αβ or γδ T cells.14

Clinical features

ENKTL nasal type presents within the adult population as multiple erythematous to violaceous plaques or tumors, usually ulcerated, involving the trunk and extremities (Figure 1). Clinical examination or imaging studies may elucidate nasal or midfacial destructive and/or necrotic tumors.1 Upper respiratory tract and oral cavity involvement may manifest in nasal obstruction or epistaxis. Fever, malaise, and weight loss may occur, with occasional hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH).1,5

FIGURE 1.

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type, variable clinical presentation. (A) Ulcerated plaques on the lower extremities. (B) Numerous erythematous-violaceous plaques on the chest. (C) Annular and round plaques of 1–2 cm with hemorrhagic crusts in volving the thigh. Abbreviation: NK, natural killer.

Histopathologic features

Architecturally, ENKTL localizes to vascular structures as multinodular plus/minus interstitial-to-diffuse dermal and subcutaneous infiltrates that encroach upon epithelial and connective tissues to cause cytotoxic damage (Figure 2A and 2B). Angiocentricity and vascular destruction1 are prominent and are accompanied by necrosis.5 Predominant involvement of the subcutis may be observed, mimicking panniculitis-like T-lymphoma (Figure 2C).15 Cell size ranges from small to large, but most infiltrates are composed of medium-sized, pleomorphic, hyperchromatic NK or T cells.1 Heavy reactive infiltrates of small lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils are not uncommon.1

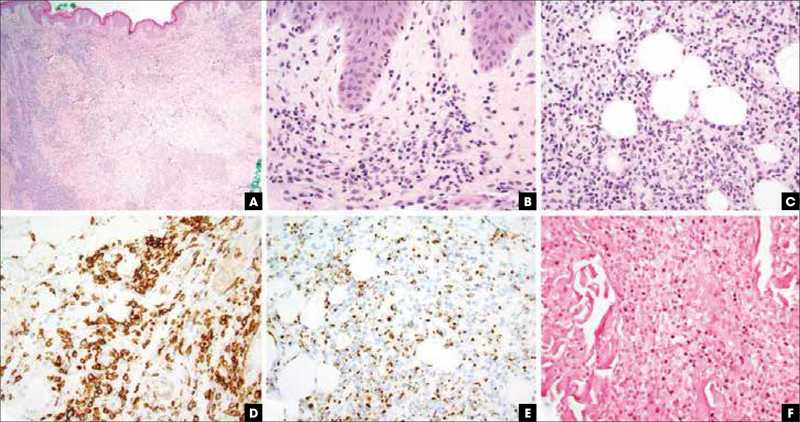

FIGURE 2.

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type, pathologic features. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 20x, leukemic appearing multinodular, perivascular, and periadnexal mononuclear cell infiltrate. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 400x, vacuolar interface alteration at the dermoepidermal junction and extravasated erythrocytes admixed with perivascular NK and/or T cells, evidencing cytotoxic damage. (C) Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 400x, lobular panniculitic infiltrates. (D) CD56 immunohistochemistry highlights the atypical NK cells. (E) Granzyme B immunohistochemistry is diffusely positive. (F) Epstein–Barr virus encoded RNA in situ hybridization study revealing nuclear virus positivity in many of the atypical cells. NK, natural killer.

Immunohistochemically, the neoplastic cells are positive for CD2, CD56, and cytotoxic proteins (TIA-1, granzyme B, perforin; Figure 2D-E). T-cell surface markers such as CD3, CD4, CD8, CD5, CD7, TCRβ, and TCRδ are negative within NK-cell phenotypes, while about 10% of ENKTL are of T-cell origin and may show CD4 or CD8 positivity with TCR αβ or γδ.14 Cytoplasmic CD3 labeling in the context of negative membranous labeling can be used to favor this diagnosis with flow cytometry. The use of CD3 localization as a discriminant purely on fixed tissues is less reliable.

EBV is almost always demonstrated by in situ hybridization in the majority of the neoplastic cells (Figure 2F).8,16 In rare CD56 negative cases, the detection of EBV and expression of cytotoxic proteins are required for diagnosis.1 A negative EBV result should raise serious doubts on the diagnosis of ENKTL. Measuring circulating EBV DNA can be used to determine a treatment algorithm and provide prognostic information.4,16

Germline configuration of the T-cell receptor (TCR) genes is most often seen.17 Clonal rearrangement of the TCR genes can be seen in T-cell-derived ENKTL cases. T-cell ENKTL cases are not distinguished clinically from NK-phenotype ENKTL nasal type.4,14

Differential diagnosis

In most cases of ENKTL, the tumor cells have an NK phenotype; however, a subset of ENKTLs are of T-cell origin.14 The combination of negative T-cell markers, germline rearrangement of TCR genes, and EBV detection in neoplastic cells strongly supports ENKTL; however, distinction from other aggressive cutaneous lymphomas such as PCGDTCL can be difficult. Strong EBV positivity would be difficult to accept in PCGDTCL, would favor ENKTL or an immunodeficiency-related peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), and should prompt a more thorough evaluation. Lack of CD5 expression and polyclonal TCR gene rearrangements would favor an NK-cell process over PCGDTCL.14

ENKTL nasal type can mimic MF clinically in early stages. While epidermotropism can be seen in both MF and ENKTL, classic (CD4+) lesions of MF should not exhibit morphologic evidence of cytotoxic damage to the dermoepidermal junction or underlying structures. Such a finding should prompt further evaluation. Absence of CD4, germline TCR configuration, and CD56 and EBV positivity should enable the correct diagnosis18 in these cases. Subcutaneous ENKTL nasal type mimicking SPTCL, confined to the subcutaneous fat, can be distinguished by the absence of CD8 and present EBV positivity and polyclonal TCR gene rearrangements in progressing disease.15 Hydroa-vacciniforme (HV), HV-like lymphoma, and hypersensitivity to mosquito bites2 may also be included in the clinical differential diagnosis but may be distinguished by clinical features.

Other EBV-positive lymphomas such as lymphomatoid granulomatosis (LYG) or EBV-positive mucocutaneous ulcer (MCU) are of B-cell origin and usually express pan-B-cell markers.2 However, variants of MCU including therapy-related lesions may show mixed or T-cell lineage, complicating the diagnosis, and LYG involving skin may exhibit few B cells, requiring a high index of suspicion and extensive clinical correlation; the identification of systemic, often pulmonary disease usually helps to clarify the diagnosis of LYG. The differential diagnosis may also include other NK malignancies, such as aggressive NK-cell leukemia, which presents in younger patients with an absence of mass-forming lesions, greater CD16 positivity and rapid decline,19 and PTCL cases that are CD56 positive but EBV negative.6

ENKTL-NT can resemble clinically other sinonasal and oropharyngeal disorders, such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis), invasive fungal infections,4 or nasopharyngeal malignancies such as squamous cell carcinoma. Biopsy should facilitate these differential diagnoses.

Therapy

Because of its rarity and the lack of randomized controlled trials, a standard treatment for ENKTL is still unknown. Cases with skin involvement alone should be treated in the same manner as those with extracutaneous involvement.7 Radiotherapy (RT), systemic chemotherapy, or combined therapy are considered as the first choice of treatment, but the results are disappointing and relapses are frequent.7,20 A meta-analysis showed that radiochemotherapy does not improve the outcomes compared to RT alone.21 Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT) should be considered in some cases; however the role and timing of autologous and allogeneic HSCT are still unclear.4

Primary cutaneous CD8+ aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma

PCAE-TCL is a rare cutaneous lymphoma, representing <1% of all cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) cases.22 It is characterized by a proliferation of cytotoxic CD8-positive T cells with preferential localization to the epidermis resulting in extensive keratinocyte necrosis and clinical ulceration. PCAE-TCL is characterized by aggressive clinical behavior with rapid progression and poor response to conventional therapies. The 5-year overall survival rate ranges from 18%−32%.23,24 The median overall survival ranges from 12–32 months.23,25 PCAE-TCL was classified as a provisional cutaneous lymphoma entity by the WHO/EORTC in 2005.1,23,25,26

Clinical features

PCAE-TCL affects mostly middle-aged and elderly male patients,23,24,26 who clinically present with the abrupt onset of an ulcerating skin eruption that progresses quickly. Papules, plaques, and tumors with central necrosis and hemorrhagic crust are distributed mostly on the extremities and the trunk (Figure 3) with occasional involvement of the oral cavity or the genitals. Localized disease to one anatomic region or a solitary lesion has been described in a minority of cases; this presentation should prompt close evaluation of the diagnosis.23,24,26 In some cases, a chronic course longer than 6 months with poorly characterized preceding skin lesions is depicted by the patient.23 Bona fide bone marrow and lymph node involvement are uncommon; however, small reactive lymphadenopathy may be noted.23,26 Disease may disseminate rapidly to visceral sites, including the lung,23 adrenal glands,23 testis,25 and the central nervous system.25

FIGURE 3.

Primary cutaneous CD8+ aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma, clinical examples. (A) Papules with hemorrhagic crust on the back. (B) Papules and diffuse plaques with focal necrosis and hemorrhagic crust on the back and upper extremities.

Histopathologic features

Histopathology shows a prominent epidermotropic proliferation of small-medium or medium-large atypical lymphocytes (Figure 4A), which may exhibit blastic nuclei.1,25 A pagetoid array of lymphocytes involving either the lower levels or the full thickness of the epidermis with or without aggregates of lymphocytes resembling Pautrier’s microabscesses can be observed.23 Focal to confluent keratinocyte necrosis and ulceration are frequently seen; however, signs of cytotoxicity may be limited to subtle vacuolar interface alteration and sparse dermal melanophages. Upper dermal extravasation of erythrocytes is common (Figure 4B), and biopsies of clinical tumors show dermal and subcutaneous infiltration, the latter without adipocyte rimming. Invasion and destruction of cutaneous adnexa can be found (Figure 4C), usually without follicular mucinosis or destruction of the follicular unit.23 Angiocentricity and angioinvasion are inconsistently reported.23,26

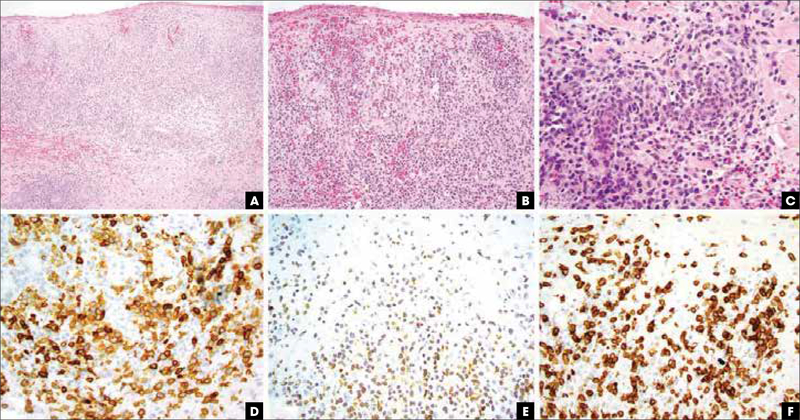

FIGURE 4.

Primary cutaneous CD8+ aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma, pathologic features. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin, 20x, epidermal and dermal infiltration by a high-grade lymphoma. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin, 400x, epidermotropic lymphocytes in aggregates and in a buckshot pattern with hemorrhage. (C) Hematoxylin and eosin, 400x, destruction of eccrine ducts by large cytotoxic lymphocytes. (D) Immunohistochemistry for CD8 highlights malignant cells. (E) Immunohistochemistry for T-cell receptor beta chain showing diffuse positive aberrant labeling of the same population. (F) Immunohistochemistry for CD7 shows retention of this pan-T-cell marker, assisting in a distinction from mycosis fungoides.

Immunohistochemical evaluation shows that the tumor cells are CD3+, CD8+ (Figure 4D), cytotoxic granule positive (granzyme B, perforin, and TIA-1), βF1+ (Figure 4E), CD45RA+, and CD45RO–. CD7 is often positive (Figure 4F), while CD2, CD4, and CD5 are negative in the tumor cells. EBV should be negative for a definitive diagnosis. The Ki-67 proliferation index is high.25,26 The neoplastic cells have clonal TCR gene rearrangements.1,24

Cases with CD4/CD8 double-negativity and cases with αβ/γδ double-positive or double-negative expression that otherwise fulfilled the clinical and pathological characteristics of this entity have been presented with the suggestion that the wider term “primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma” may be better suited for these tumors, which would group cases regardless of CD8 or TCR status, as long as at least one T-cell marker and one marker of cytotoxicity are expressed.23

Differential diagnosis

Differentiating PCAE-TCL from other types of CTCL expressing a CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell phenotype is often dependent upon clinicopathological correlation. CD8+ MF patients present with a history of a prolonged course of patches and plaques unlike the more common acute onset and rapid progression in PCAE-TCL. CD8+ MF often correlates with clinically hypopigmented, hyperpigmented, or poikilodermatous lesions that do not ulcerate and infrequently progress to tumor stage, although these lesions have also been said to have a course indistinguishable from conventional CD4+ MF.27 The non-robust infiltration and limited localization of smaller T cells as a “lining” at the dermoepidermal junction with rare necrotic keratinocytes typical for CD8+ MF would not be sufficient for a diagnosis of PCAE-TCL.

Pagetoid reticulosis (PR) or Woringer-Kolopp disease is a localized variant of MF characterized by a solitary psoriasiform or hyperkeratotic patch or plaque that is usually localized on the extremities and does not disseminate.1 PR shows marked pagetoid epidermotropic infiltration by T cells with frequent CD8 predominance28; the clinical history is critical for the correct diagnosis in these patients.

Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) is a CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by waxing and waning papules and small nodules that can centrally ulcerate but overall has a favorable prognosis. Type D LyP2,29 is a cytotoxic variant of LyP often composed of medium-sized pleomorphic CD8+ lymphocytes infiltrating the epidermis in a pagetoid pattern. CD30 is not definitively helpful as PCAE-TCL with CD30 has been reported.23 LyP type D is usually diagnosed in young adults (mean age of 29) who present with self-resolving or treatment-responsive papular rashes rather than the progressive ulcerated large plaques and tumors in patients with PCAE-TCL.29,30

The rare PCAE-TCL can be clinically misdiagnosed as more common inflammatory dermatoses such as pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis or Mucha-Haberman disease that often has a CD8+ phenotype and possible monoclonal TCR rearrangement,29,31 and pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema multiforme.32 Histology and immunohistochemical studies allow a distinction between these entities.

Therapy

Because of its aggressive and rapidly progressing course, PCAETCL should be accurately and timely diagnosed, and aggressive treatment strategies such as multiagent chemotherapy and HSCT are needed. In a retrospective study, 34 patients were treated with different modalities, including oral bexarotene, romidepsin, etoposide, gemcitabine, liposomal doxorubicin, local radiation, and total skin electron beam therapy, and none showed significant survival advantage. Allogeneic HSCT resulted in prolonged partial or complete remissions in 5 of 6 patients.23 Few case reports of complete response after allogeneic and autologous HSCT suggest that it should be included early in the therapeutic consideration in selected cases of PCAE-TCL.33,34

Primary cutaneous gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma

PCGDTCL is a distinct entity composed of a clonal proliferation of mature, activated T cells expressing TCR γ/δ and cytotoxic molecules, with a relatively heterogeneous spectrum of clinical and histologic features.1,35,36 PCGDTCL is rare, comprising <1% of all skin lymphomas,1 and its incidence is low. The γ/δ phenotype in T-cell lymphoma is usually associated with therapy resistance and poor prognosis.1,36,37 PCGDTCL patients have 5-year overall survival rates ranging from 11%−33%36–39 and a median survival of 15 months.36 Individuals with subcutaneous infiltrates were shown to have a statistically significant decreased survival in comparison to individuals who have epidermal or dermal involvement (median of 13 versus- 29 months),36 although the authors’ experience does not confirm this finding.

The first cases of PCGDTCL, which were characterized and reported in 1991, showed diverse clinical presentations and histological patterns,40,41 overlapping with other cytotoxic and non-cytotoxic CTCL subtypes. PCGDTCL was classified as a provisional cutaneous lymphoma entity by the WHO/EORTC in 20051 and as a definitive entity in the 2008 WHO lymphoma classification.39 A lack of reliable immunohistochemical markers for the detection of the TCR γ/δ chains, controversy over the positive predictive value of absent TCR α/β labeling, the presence of reactive γδ T-cell subsets in indolent cutaneous lymphoma types,42 and inexperience in the interpretation of these infiltrates have made this a challenging diagnosis.

Clinical features

The clinical presentation of PCGDTCL is variable. Patients generally present with large and deep indurated plaques, tumors, or nodules that may resemble panniculitis and commonly show superimposed superficial erosive or ulcerated or necrotic features (Figure 5A-B).38 PCGDTCL usually involves the extremities, but other sites can be affected.1,37,39 Some patients present with MF-like or psoriasis-like erythematous and scaly patches that later evolve into aggressive disease with ulceration (Figure 5C-D).39 While PCGDTCL can appear as generalized disease or as solitary or multiple lesions confined to one anatomic site, the skin tumor burden does not appear to correlate with prognosis.39 Mucosal and gastrointestinal lesions are rare,39 and lymph node and bone marrow are mostly uninvolved.1,39 The patients often have B symptoms, including fever, night sweats, and weight loss. HLH including fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and cytopenia may accompany this disease, especially in patients with subcutaneous lesions.37,43

FIGURE 5.

Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma, variable clinical presentation. (A) Ulcerated nodule on the anterior leg. (B) Violecous patches and plaques with focal erosions on the thighs. (C-D) Erythematous and scaly patches resembling mycosis fungoides on the legs that later evolved to ulcerated plaques.

Histopathologic features

Similarly to the NK/T-cell lymphomas in skin, common features of PCGDTCL are of perivascular infiltrates with cytotoxic damage to the dermoepidermal junction and underlying dermal and subcutaneous tissues (Figure 6A). PCGTCL has been described as exhibiting epidermotropic, dermal, and subcutaneous patterns (Figure 6B-C),37,39 each of which can be present in the same patient and are not infrequently found within the same lesion.1 A subcutaneous pattern similar to that of SPTCL shows tumor cells that infiltrate the fat lobules with focal involvement of the septae and rimming of individual adipocytes, but with more exuberant infiltration of the dermis and/or epidermis.36,38 Epidermal involvement can be composed of an interface reaction with vacuolar degeneration or by pagetoid lymphocytes accompanied by intraepidermal vesiculation and necrotic keratinocytes. Dermal involvement ranges from mild perivascular to deep nodular to diffuse lymphoid infiltrates.39 Tumor cells are usually characterized by medium-to large-sized pleomorphic cells. Apoptotic cells are frequent, and areas of hemorrhage and necrosis and signs of vascular invasion are common.1 Large macrophages engulfing neoplastic lymphocytes or other blood cells can be seen with or without HLH.37,38

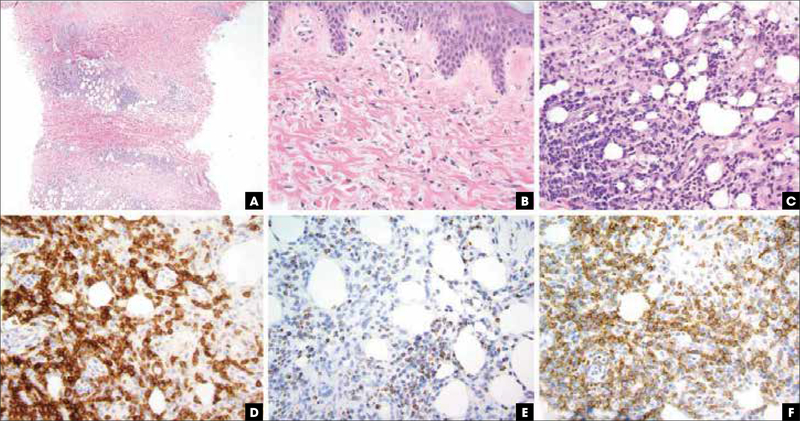

FIGURE 6.

Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma, pathologic features. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin, 20x, zonal dermal and subcutaneous infiltrates of atypical and hyperchromatic cells. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin, 400x, interface changes with subtle dermal alteration suggestive of connective tissue damage by cytotoxic mediators. (C) Hematoxylin and eosin, 400x, lobular panniculitis composed of high-grade-appearing lymphocytic infiltrate, with absence of clear adipocyte rimming. (D) Immunohistochemistry for TCR delta chain with strong diffuse labeling. (E) Immunohistochemistry for TIA-1. (F) Immunohistochemistry for CD56 highlighting malignant cells. TCR, T-cell receptor; TIA, T-cell intracellular antigen.

Immunohistochemical stains show that the cells are typically positive for CD3, TCRδ (Figure 6D),44 and TCRγ and are negative for CD5. CD4 and CD8 are often simultaneously negative (“double negative”), though CD8 may be expressed in some cases.37 We have seen PCGTCL patients who harbor both CD8+ and double negative tumors. At least a subset of cells typically express cytotoxic molecules (Figure 6E).39 CD7 and CD56 may be positive or negative (Figure 6F). The neoplastic T cells express TCR γ and δ chains rather than TCR α/β, as demonstrated by immunolabeling of TCR γ or δ chain on fresh-frozen tissue or formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections or indirectly by the lack of βF1 expression.1,37 EBV is generally not present in the neoplastic cells.1 Molecular studies typically show a monoclonal rearrangement of the TCR genes.37,39

Differential diagnosis

γδ-expressing T cells are not wholly limited to PCGDTCL and are also present in low-grade cutaneous lymphomas, lymphoproliferative disorders,45 and inflammatory skin disorders as part of the innate immune response.46,47 Other cutaneous disorders may have a small population of γδ T cells as part of the mononuclear cell infiltrate. Moreover, lymphoid infiltrates with a predominant γδ phenotype are not unequivocally associated with aggressive disease and can be found in cases of indolent lesions such as lym-phomatoid papulosis and pityriasis lichenoides.42,48 However, the majority of PCGDTCL can be efficiently diagnosed with an adequate cutaneous punch or core biopsy and accurate clinicopathologic correlation. Often difficulties in diagnosing this disease arise from inadequate (eg, too superficial or too narrow) biopsy material or poor clinical history.

Subcutaneously localized PCGDTCL shares some clinical and histologic features with SPTCL, including expression of cytotoxic molecules and the presence of an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate with rimming of adipocytes in the subcutis.36 Morphologically, the infiltrates of PCGDTCL do not limit themselves to the fat, and when they do, the infiltration of the fat is uneven. While adipocyte rimming is said to be less pronounced in gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma (GDTCL) compared to SPTCL,38 in our experience, adipocyte rimming in GDTCL is present but composed of the non-neoplastic components of the infiltrates. PCGDTCL tends to involve epidermis and dermis more significantly than SPTCL.36 Frank necrosis can be seen in PCGDTCL38 but is not characteristic of SPTCL. Most importantly, the tumor cells of PCGDTCL are TCR γ/δ+, CD4/CD8 double negative, while in SPTCL the cells are TCR α/β+ and CD8+.36 Of note, careful correlation of TCR-β and TCR-δ immunohistochemical stains and T-cell subset markers such as CD8 are warranted, as some cases of PCGDTCL seem to have a discrete prominent reactive component of CD8+ T cells, and SPTCLs may have up to 10%−20% γδ T cells within their infiltrates.49

Although some PCGDTCL cases present with epidermotropic involvement that can resemble MF clinically and histopathologically, unequivocal/bona fide PCGDTCL behaves differently than classic MF, and its characteristic ulcerations at presentation or soon after onset are uncommon in MF. The long-standing patches and plaques that characterize MF in preceding or accompanying tumor stage development are typically absent in PCGDTCL. The neoplastic cells in PCGDTCL lack the convoluted cerebriform morphology and expression of βF1 and CD4 that are commonly seen in MF.37 Classic MF does not typically show the prominent cytotoxic interface and perivascular destruction that may accompany PCGDTCL. There are occasional cases of MF-like cutaneous T-cell lymphoma with expression of γ and/or δ chains; however, these cases are poorly characterized and warrant further investigation.23

Panniculitic T-cell lymphomas, including PCGDTCL have overlapping features with lupus erythematosus panniculitis (LEP),50 and some of the patients occasionally have a prior diagnosis of LEP.39 Lymphoid atypia has been described in LEP, thus making differentiation between LEP and panniculitis-like lymphomas difficult.49 Clues such as lupus history, extracutaneous signs and symptoms, and serology data can help to differentiate these cases. Unlike inflammatory panniculitis, PCGDTCL is usually more extensive, with a progressive course of disease, a tendency to ulcerate, and a lack of response to therapy. Immunohistochemistry and molecular analysis should be correlated with clinical and histological features in such cases.50

The clinical impression of localized PCGDTCL lesions often includes conditions like cellulitis, hematoma, pyoderma, or an arthropod bite reaction. Histological features do not support the above benign diagnoses.39

The differential diagnosis of PCGDTCL includes other cytotoxic entities such as ENKTL nasal type14 and PCAE-TCL, and overlapping features make the diagnosis challenging; ancillary studies are essential to differentiate these entities. The distinction of PCGDTCL from systemic GDTCL (hepatosplenic gamma delta T-cell lymphoma [HSGDTCL]) requires correlation with the clinical history, radiologic imaging, and staging biopsies. Histologically, cutaneous involvement by HSGDTCL may show more diffuse infiltration of the skin by a more monomorphic population of γδ chain+ T cells than is seen in PCGDTCL.

Therapy

All therapies in PCGDTCL have shown modest effectiveness, and disease resistance to multi-agent chemotherapy is not uncommon.36,38,39 HSCT has been successful in some patients.38,39,51

Reports of indolent cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphomas were recently questioned and were suggested to be a result of short follow-up periods or misdiagnosis caused by lack of awareness to reactive γδ T cells in subcutaneous infiltrates.23 Systemic chemotherapy is the recommended approach in cases that present with aggressive clinical course, and HSCT should be considered in selected patients.

Conclusion

While indolent CTCL entities, such as MF and primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder, account for approximately 90% of all CTCL cases, rare CTCL types have an aggressive clinical course and are associated with poor treatment response and high mortality. These aggressive entities, derived from cytotoxic NK cells, CD8+ αβ T cells, and γδ T lymphocytes, have heterogeneous and typically atypical presentations and confer diagnostic and therapeutic challenges to dermatologists, pathologists, and oncologists.

In the past 20 years, persistent efforts have been made to better characterize these aggressive cutaneous lymphoma entities. Future studies will further delineate the pathogenesis of these aggressive CTCLs and will result in advanced diagnostic abilities and therapeutic options that will eventually improve outcomes in patients with aggressive cytotoxic lymphomas of the skin.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Disclosures: Dr Geller, Dr Myskowski, and Dr Pulitzer report grants from NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748, during the conduct of the study.

References

- 1.Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105(10):3768–3785. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127(20):2375–2390. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-643569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Massone C, Crisman G, Kerl H, Cerroni L. The prognosis of early mycosis fungoides is not influenced by phenotype and T-cell clonality. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(4):881–886. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08761.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haverkos BM, Pan Z, Gru AA, et al. Extranodal NK/T Cell Lymphoma, Nasal Type (ENKTL-NT): An Update on Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, and Natural History in North American and European Cases. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2016;11(6):514–527. doi: 10.1007/s11899-016-0355-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaffe ES, Chan JK, Su IJ, et al. Report of the Workshop on Nasal and Related Extranodal Angiocentric T/Natural Killer Cell Lymphomas. Definitions, differential diagnosis, and epidemiology. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20(1):103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takata K, Hong ME, Sitthinamsuwan P, et al. Primary cutaneous NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type and CD56-positive peripheral T-cell lymphoma: a cellular lineage and clinicopathologic study of 60 patients from Asia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39(1):1–12. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bekkenk MW, Jansen PM, Meijer CJ, Willemze R. CD56+ hematological neoplasms presenting in the skin: a retrospective analysis of 23 new cases and 130 cases from the literature. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(7):1097–1108. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan JK, Sin VC, Wong KF, et al. Nonnasal lymphoma expressing the natural killer cell marker CD56: a clinicopathologic study of 49 cases of an uncommon aggressive neoplasm. Blood. 1997;89(12):4501–4513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fink-Puches R, Zenahlik P, Bäck B, Smolle J, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Primary cutaneous lymphomas: applicability of current classification schemes (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, World Health Organization) based on clinicopathologic features observed in a large group of patients. Blood. 2002;99(3):800805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi YL, Park JH, Namkung JH, et al. Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma with cutaneous involvement: ‘nasal’ vs. ‘nasal-type’ subgroups--a retrospective study of 18 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160(2):333–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08922.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki R, Suzumiya J, Yamaguchi M, et al. Prognostic factors for mature natural killer (NK) cell neoplasms: aggressive NK cell leukemia and extranodal NK cell lymphoma, nasal type. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(5):1032–1040. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsieh PP, Tung CL, Chan AB, et al. EBV viral load in tumor tissue is an important prognostic indicator for nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128(4):579–584. doi: 10.1309/MN4Y8HLQWKD9NB5E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Diebold J, et al. World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: report of the Clinical Advisory Committee meeting-Airlie House, Virginia, November 1997. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(12):3835–3849. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.12.3835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pongpruttipan T, Sukpanichnant S, Assanasen T, et al. Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type, includes cases of natural killer cell and αβ, γδ, and αβ/γδ T-cell origin: a comprehensive clinicopathologic and phenotypic study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(4):481–499. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31824433d8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massone C, Lozzi GP, Egberts F, et al. The protean spectrum of non-Hodgkin lymphomas with prominent involvement of subcutaneous fat. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33(6):418–425. doi: 10.1111/j.0303-6987.2006.00493.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pulitzer M Molecular diagnosis of infection-related cancers in dermatopathology. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2012;31(4):247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2012.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emile JF, Boulland ML, Haioun C, et al. CD5-CD56+ T-cell receptor silent peripheral T-cell lymphomas are natural killer cell lymphomas. Blood. 1996;87(4):1466–1473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massone C, Chott A, Metze D, et al. Subcutaneous, blastic natural killer (NK), NK/T-cell, and other cytotoxic lymphomas of the skin: a morphologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular study of 50 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(6):719–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nazarullah A, Don M, Linhares Y, Alkan S, Huang Q. Aggressive NK-cell leukemia: A rare entity with diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Hum Pathol: Case Rep. 2016;4:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ehpc.2015.08.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim K, Chie EK, Kim CW, Kim IH, Park CI. Treatment outcome of angiocentric Tcell and NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type: radiotherapy versus chemoradiotherapy. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2005;35(1):1–5. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyi006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng T, Zhang C, Zhang X, et al. Treatment outcome of radiotherapy alone versus radiochemotherapy in IE/IIE extranodal nasal-type natural killer/T cell lymphoma: a meta-analysis. PloS One. 2014;9(9):e106577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willemze R CD30-Negative Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphomas Other than Mycosis Fungoides. Surg Pathol Clin. 2014;7(2):229–252. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2014.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guitart J, Martinez-Escala ME, Subtil A, et al. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lymphomas: reappraisal of a provisional entity in the 2016 WHO classification of cutaneous lymphomas. Mod Pathol. 2017;30(5):761–772. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nofal A, Abdel-Mawla MY, Assaf M, Salah E. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma: proposed diagnostic criteria and therapeutic evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(4):748–759. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.07.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berti E, Tomasini D, Vermeer MH, Meijer CJ, Alessi E, Willemze R. Primary cutaneous CD8-positive epidermotropic cytotoxic T cell lymphomas. A distinct clinicopathological entity with an aggressive clinical behavior. Am J Pathol. 1999;155(2):483–492. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65144-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robson A, Assaf C, Bagot M, et al. Aggressive epidermotropic cutaneous CD8+ lymphoma: a cutaneous lymphoma with distinct clinical and pathological features. Report of an EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force Workshop. Histopathology. 2015;67(4):425–441. doi: 10.1111/his.12371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez-Escala ME, Kantor RW, Cices A, et al. CD8+ mycosis fungoides: A low-grade lymphoproliferative disorder. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(3):489–496. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haghighi B, Smoller BR, LeBoit PE, Warnke RA, Sander CA, Kohler S. Pagetoid reticulosis (Woringer-Kolopp disease): an immunophenotypic, molecular, and clinicopathologic study. Mod Pathol. 2000;13(5):502–510. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saggini A, Gulia A, Argenyi Z, et al. A variant of lymphomatoid papulosis simulating primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma. Description of 9 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(8):1168–1175. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181e75356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marschalkó M, Gyöngyösi N, Noll J, et al. Histopathological aspects and differential diagnosis of CD8 positive lymphomatoid papulosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43(11):963–973. doi: 10.1111/cup.12779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheng N, Li Z, Su W, et al. A Case of Primary Cutaneous Aggressive Epidermotropic CD8+ Cytotoxic T-cell Lymphoma Misdiagnosed as Febrile Ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann Disease. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96(1):136–137. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomasini C, Novelli M, Fanoni D, Berti EF. Erythema multiforme-like lesions in primary cutaneous aggressive cytotoxic epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma: A diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44(10):867–873. doi: 10.1111/cup.12995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Plachouri KM, Weishaupt C, Metze D, et al. Complete durable remission of a fulminant primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma after autologous and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3(3):196–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wehkamp U, Glaeser D, Oschlies I, Hilgendorf I, Klapper W, Weichenthal M. Successful stem cell transplantation in a patient with primary cutaneous aggressive cytotoxic epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(3):869–871. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaffe ES. The 2008. WHO classification of lymphomas: implications for clinical practice and translational research. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009:523–531. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2009.1.523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toro JR, Liewehr DJ, Pabby N, et al. Gamma-delta T-cell phenotype is associated with significantly decreased survival in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2003;101(9):3407–3412. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toro JR, Beaty M, Sorbara L, et al. gamma delta T-cell lymphoma of the skin: a clinical, microscopic, and molecular study. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136(8):1024–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Willemze R, Jansen PM, Cerroni L, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: definition, classification, and prognostic factors: an EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Group Study of 83 cases. Blood. 2008;111(2):838–845. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-087288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guitart J, Weisenburger DD, Subtil A, et al. Cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphomas: a spectrum of presentations with overlap with other cytotoxic lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(11):1656–1665. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31826a5038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berti E, Cerri A, Cavicchini S, et al. Primary cutaneous gamma/delta T-cell lymphoma presenting as disseminated pagetoid reticulosis. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96(5):718–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burg G, Dummer R, Wilhelm M, et al. A subcutaneous delta-positive T-cell lymphoma that produces interferon gamma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(15):1078–1081. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110103251506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guitart J, Martinez-Escala ME. γδ T-cell in cutaneous and subcutaneous lymphoid infiltrates: malignant or not? J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43(12):1242–1244. doi: 10.1111/cup.12830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tripodo C, Iannitto E, Florena AM, et al. Gamma-delta T-cell lymphomas. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6(12):707–717. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jungbluth AA F D, Fayad M, Pulitzer MP, Dogan A, Busam KJ, Imai N, Gnjatic S. Immunohistochemical Detection of γ/δ T-Lymphocytes in Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded Tissues Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2018. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodríguez-Pinilla SM, Ortiz-Romero PL, Monsalvez V, et al. TCR-γexpression in primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37(3):375–384. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318275d1a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dupuy P, Heslan M, Fraitag S, Hercend T, Dubertret L, Bagot M. T-cell receptorgamma/delta bearing lymphocytes in normal and inflammatory human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1990;94(6):764–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roullet M, Gheith SM, Mauger J, Junkins-Hopkins JM, Choi JK. Percentage of {gamma}{delta} T cells in panniculitis by paraffin immunohistochemical analysis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131(6):820–826. doi: 10.1309/AJCPMG37MXKYPUBE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martinez-Escala ME, Sidiropoulos M, Deonizio J, Gerami P, Kadin ME, Guitart J. γδ T-cell-rich variants of pityriasis lichenoides and lymphomatoid papulosis: benign cutaneous disorders to be distinguished from aggressive cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphomas. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(2):372–379. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Magro CM, Crowson AN, Kovatich AJ, Burns F. Lupus profundus, indeterminate lymphocytic lobular panniculitis and subcutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a spectrum of subcuticular T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28(5):235–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aguilera P, Mascaró JM Jr, Martinez A, et al. Cutaneous gamma/delta T-cell lymphoma: a histopathologic mimicker of lupus erythematosus profundus (lupus panniculitis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(4):643–647. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gibson JF, Alpdogan O, Subtil A, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma and refractory subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(6):1010–1015.e1015. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]