Abstract

In this work a photosubstitution strategy is presented that can be used for the isolation of chiral organometallic complexes. A series of five cyclometalated complexes Ru(phbpy)(N−N)(DMSO-κS)](PF6) ([1]PF6-[5]PF6) were synthesized and characterized, where Hphbpy = 6′-phenyl-2,2′-bipyridyl, and N–N = bpy (2,2′-bipyridine), phen (1,10-phenanthroline), dpq (pyrazino[2,3-f][1,10]phenanthroline), dppz (dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine, or dppn (benzo[i]dipyrido[3,2-a,2′,3′-c]phenazine), respectively. Due to the asymmetry of the cyclometalated phbpy– ligand, the corresponding [Ru(phbpy)(N–N)(DMSO-κS)]+complexes are chiral. The exceptional thermal inertness of the Ru–S bond made chiral resolution of these complexes by thermal ligand exchange impossible. However, photosubstitution by visible light irradiation in acetonitrile was possible for three of the five complexes ([1]PF6-[3]PF6). Further thermal coordination of the chiral sulfoxide (R)-methyl p-tolylsulfoxide to the photoproduct [Ru(phbpy)(phen)(NCMe)]PF6, followed by reverse phase HPLC, led to the separation and characterization of the two diastereoisomers of [Ru(phbpy)(phen)(MeSO(C7H7))]PF6, thus providing a new photochemical approach toward the synthesis of chiral cyclometalated ruthenium(II) complexes. Full photochemical, electrochemical, and frontier orbital characterization of the cyclometalated complexes [1]PF6-[5]PF6 was performed to explain why [4]PF6 and [5]PF6 are photochemically inert while [1]PF6-[3]PF6 perform selective photosubstitution.

Introduction

Since the clinical approval of cisplatin a great number of inorganic complexes with anticancer properties have been described, among which several ruthenium complexes have reached clinical trials. Currently, most research is focused on either compounds based upon the piano-stool Ru(II)η6-arene scaffold pioneered by the groups of Dyson and Sadler1,2 or ruthenium(II) polypyridyl complexes, of which several (photoactive) candidates have been developed by the groups of Dunbar,3 Gasser,4 Glazer,5 Renfrew,6 Keyes,7,8 Kodanko,9,10 or Turro.11 More recently cyclometalated analogues of these complexes have emerged as a new subclass of light-activatable anticancer complexes.3,12,13 In this type of compounds, one nitrogen atom in a polypyridyl ligand has been replaced by a carbon atom, resulting in an organometallic metallacycle.14−17 As a consequence, cyclometalated compounds often show enhanced properties for chemotherapy or photodynamic therapy (PDT) than their noncyclometalated analogons.14 In particular, the lower charge of cyclometalated complexes leads to an increased lipophilicity, which in turn increases uptake in cancer cells18 and often leads to higher cytotoxicity19 toward cancer cells. In addition, cycloruthenated polypyridyl complexes have increased absorption in the red region of the spectrum, which is excellent for photochemotherapy. Whereas polypyridyl ruthenium complexes typically absorb between 400 and 600 nm,20 a bathochromic shift is usually observed for cyclometalated compounds due to the destabilization of t2g orbitals by the π-donating cyclometalated carbanionic ligand, potentially allowing activation of these compounds in the photodynamic window, (600–1000 nm) where light penetrates further into biological tissue.21 Although cyclometalation often leads to a significant decrease of the photosubstitution properties of ruthenium complexes, the group of Turro has reported two cyclometalated complexes, cis-[Ru(phpy)(phen)(MeCN)2]PF6 and cis-[Ru(phpy)(bpy)(MeCN)2]PF6, (phpy = 2-phenylpyridine), that are capable of exchanging their acetonitrile ligand upon light irradiation and are phototoxic in cancer cells.22

Inspired by this work and following our investigation of caged ruthenium complexes with the general formula [Ru(tpy)(N–N)(L)]2+ in which L is a sulfur-based ligand and tpy = 2,2′;6′,2″-terpyridine, we herein investigated the preparation and properties of cycometalated analogues of this family of complexes where the carbanion is introduced in the tridentate ligand. Five complexes [1]PF6–[5]PF6 with the general formula [Ru(phbpy)(N–N)(DMSO-κS)]PF6 with Hphbpy = 6′-phenyl-2,2′-bipyridyl and N–N = bpy (2,2′-bipyridine, [1]PF6), phen (1,10-phenanthroline, [2]PF6), dpq (pyrazino[2,3-f][1,10]phenanthroline, [3]PF6), dppz (dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine), [4]PF6), and dppn (benzo[i]dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine, [5]PF6), respectively, were considered. Interestingly, by replacing one of the lateral nitrogen atoms of terpyridine in [Ru(tpy)(N–N)(L)]2+ by a carbon ligand, these ruthenium complexes become chiral, and using chiral monodentate sulfoxides should allow for separating their diastereomers.23−25 However, these cyclometalated complexes turned out to be substitutionally inert under thermal conditions, preventing displacement of DMSO in the racemic precursor. In order to achieve the resolution of [1]PF6, it was therefore necessary to design a photochemical route. By investigating the photophysical properties and photoreactivity of these complexes, three of these complexes were found suitable for this approach, of which one was resolved using a chiral monodentate sulfoxide ligand.

Results

Synthesis and Crystal Structures

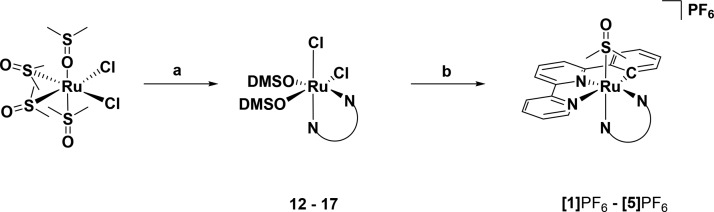

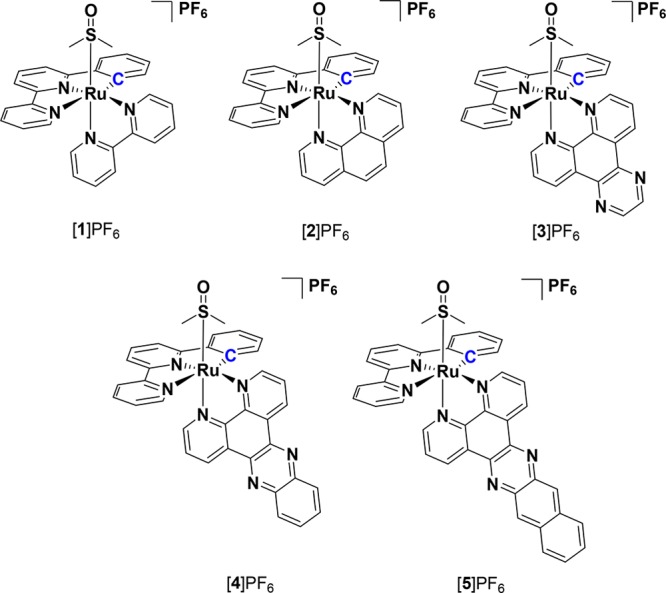

The first attempted route toward the synthesis of compounds [1]PF6–[5]PF6 (Figure 1), inspired by the report of Ryabov and co-workers,26 consisted of the coordination of the terpyridine analogon Hphbpy to the ruthenium benzene dimer [(η6-C6H6)RuCl(μ-Cl)]2. However, this approach afforded the intermediate species [Ru(phbpy)(MeCN)3]PF6 in a maximum yield of only 32% and proved to be difficult to scale up. Therefore, an alternative route depicted in Scheme 1 was developed. Starting from cis-[RuCl2(DMSO-κS)3(DMSO-κO)], the reaction of the bidentate ligand N–N = bpy, phen, dpq, dppz, or dppn was realized first, followed by cyclometalation using Hphbpy in the presence of a catalytic amount of N-methylmorpholine, affording the five compounds [Ru(phbpy)(N–N)(DMSO-κS)]PF6 ([1]PF6–[5]PF6) as a racemic mixture of enantiomers in good yield (65–74%).

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of the complexes presented in this study. [Ru(phbpy)(N–N)(DMSO-κS)]+, where N-N = bpy, phen, dpq, dppz, or dppn.

Scheme 1. Reagents and Conditions.

(a) N–N = bpy in EtOH/DMSO (15:1), reflux, 86%; (b) HPhbpy, cat. N-methylmorpholine in MeOH/H2O (5:1), reflux, 65%. For N–N = phen = 77% and 68%, N–N = dpq = 95% and 74%, N–N = dppz = 87% and 73%, NN = dppn = 96% and 65%.

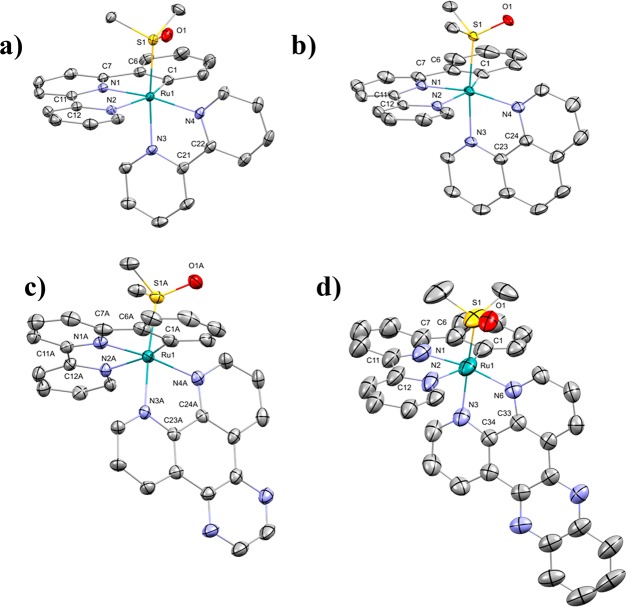

Single crystals suitable for X-ray structure determination were obtained by slow vapor diffusion of ethyl acetate in dichloromethane for [1]PF6, hexane in dichloromethane for [2]PF6 and [3]PF6, and toluene in DCM for [4]PF6. All compounds crystallized in space groups having an inversion center, thus containing a (1:1) mixture of enantiomers. A selection of bond lengths and angles is shown in Table 1. As expected, the ruthenium centers in these compounds have a distorted octahedral geometry similar to that of their terpyridyl analogues.27 Compared to [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(DMSO-κS)](OTf)2 replacing the nitrogen within this scaffold with an anionic carbon atom has only a modest effect on the corresponding bond length, with Ru1−C1 in [1]PF6 (2.043(2) Å) being almost as long as Ru1−N1 in its terpyridine analogue (2.079 Å).28 Furthermore, compared to its noncyclometalated analogon the trans-influence of the carbon atom in phbpy– results in an elongation of the Ru1–N2 bond length in [Ru(phbpy)(bpy)(DMSO-κS)]2+ (2.173(2) Å), whereas in [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(DMSO-κS)]2+ the Ru1–N3 length is 2.073(3) Å.29 In contrast, the ruthenium–sulfur bond length is shorter in [1]PF6 (2.2558(7) Å) than in [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(DMSO-κS)]2+ (2.282(1) Å) as a result of the increased electron density on ruthenium, leading to stronger backbonding into the π* orbital of the S-bound DMSO ligand. Overall, this electronic effect barely affects the angles between C1–Ru1–N3 for [1]PF6 (158.67(12) Å) and N1–Ru1–N3 for [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(DMSO-κS)]2+ (157.92(8) Å), confirming their high structural similarity (Figure 2).

Table 1. Selected Bond Distances (Å) and Bond Angles (deg) for Complexes [1]PF6, [2]PF6, [3]PF6, and [4]PF6.

| [1]PF6 | [2]PF6 | [3]PF6 | [4]PF6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ru1–S1 | 2.2558(7) | 2.2359(4) | 2.2405(9) | 2.210(3) |

| Ru1–C1 | 2.043(2) | 2.041(3) | 2.029(5) | 2.030(1) |

| Ru1–N1 | 2.002(2) | 2.004(2) | 2.005(5) | 2.019(7) |

| Ru1–N2 | 2.173(2) | 2.164(2) | 2.176(3) | 2.180(1) |

| Ru1–N3 | 2.088(2) | 2.110(2) | 2.089(3) | 2.094(3) |

| Ru1–N4 | 2.079(2) | 2.091(2) | 2.083(4) | 2.071(4) |

| S1–O1 | 1.486(2) | 1.489(2) | 1.485(3) | 1.501(6) |

| C1–Ru1–N2 | 157.92(8) | 158.45(9) | 158.5(2) | 155.6(7) |

| N3–Ru1–N4 | 78.07(7) | 78.67(7) | 78.9(1) | 78.2(1) |

| S1–Ru1–N4 | 96.25(5) | 97.29(5) | 96.6(1) | 96.0(1) |

Figure 2.

Displacement ellipsoid plots (50% probability level) of the cationic part of the crystal structure of [1]PF6 (a), [2]PF6 (b), [3]PF6 (c), and [4]PF6 (d). Hydrogen atom and counterions have been omitted for clarity.

Thermal Stability

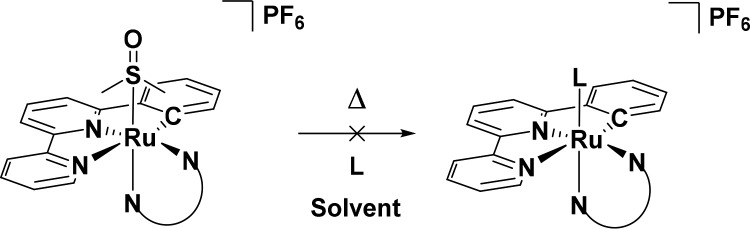

With compounds [1]PF6–[5]PF6 in hand, we first attempted to obtain diastereomers by the thermal reaction of several chiral ligands as shown in Scheme 2 and summarized in Table 2 (entries 1–6). Heating [1]PF6 and (R)-methyl p-tolylsulfoxide at increased temperatures (up to 120 °C) in DMF resulted in the formation of ruthenium(III) species, as observed by a green color, whereas lower temperatures only led to the recovery of starting materials. Further attempts to substitute the monodentate ligand with nonchiral ligands (entries 7 and 8) such as LiCl, pyridine, or acetonitrile also proved to be unsuccessful. This thermal inertness was highly unexpected, since terpyridine analogues of these complexes are known to readily exchange their monodentate ligand in similar or much milder conditions.30 The only thermal substitution possible, observed with [4](PF6)2, was obtained by prolonged heating (16 h) in acetic acid, which resulted in the partial formation of [Ru(phbpy)(dppz)(AcOH)]+ as proven by mass spectrometry (found m/z 675.1, calcd. m/z 675.1). However, this species could not be isolated. Overall, the exceptional thermal inertness of the DMSO ligand in [1]PF6–[5]PF6 required the development of an alternative strategy for the resolution of this family of chiral complexes.

Scheme 2. General Approach for the Thermal Conversion of Complexes [1]PF6, [2]PF6, and [4]PF6 with Different Monodentate Ligands L.

Table 2. Attempts of Ligand Exchange for [1]PF6, [2]PF6, and [4]PF6.

| entry | complex | ligand (L) | solvent | T (°C) | substitution | reaction time (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [1]PF6 | (R)-methyl p-tolylsulfoxide (5 equiv) | DMF | 120 | 16 | |

| 2 | [1]PF6 | (R)-methyl p-tolylsulfoxide (5 equiv) | DMF | 80 | 16 | |

| 3 | [1]PF6 | (R)-methyl p-tolylsulfoxide (5 equiv) | EtOH 3:1 H2O | 80 | 16 | |

| 4 | [4]PF6 | biotin (20 equiv) | EtOH 3:1 H2O | 80 | 16 | |

| 5 | [4]PF6 | N-acetyl-l-methionine (20 equiv) | EtOH 3:1 H2O | 80 | 16 | |

| 6 | [4]PF6 | N-acetyl-l-cysteine methyl ester (20 equiv) | EtOH 3:1 H2O | 80 | 16 | |

| 7 | [4]PF6 | l-histidine methyl ester 2HCl (20 equiv) | EtOH 3:1 H2O | 80 | 16 | |

| 8 | [2]PF6 | LiCl (20 equiv) | EtOH 3:1 H2O | 80 | 16 | |

| 9 | [4]PF6 | MeCN | 80 | 16 | ||

| 10 | [4]PF6 | pyridine | 80 | 16 | ||

| 11 | [4]PF6 | acetic acid | 80 | yes | 16 |

Photosubstitution

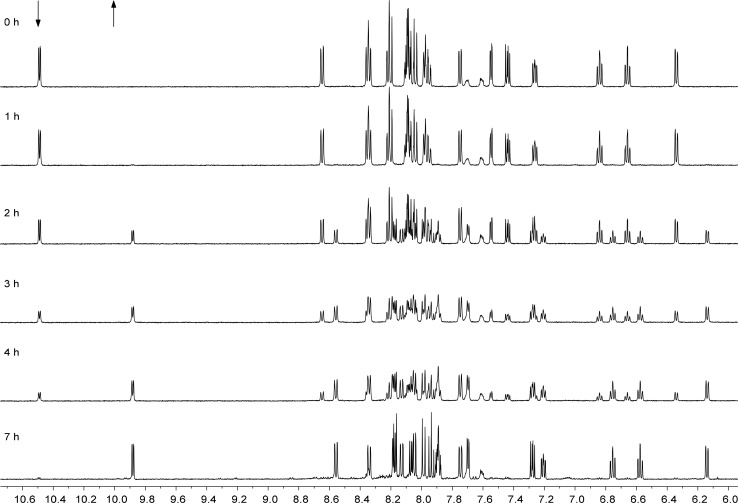

Replacing the DMSO ligands in these complexes was therefore attempted photochemically, monitoring the reaction using 1H NMR. When a sample of [2]PF6 was irradiated in acetonitrile with white light (hν ≥ 410 nm, Scheme 3), a clean photoconversion to a new species was observed, which was confirmed to be the acetonitrile adduct by mass spectrometry. As shown in Figure 3, the 1H NMR spectra clearly demonstrate the formation of the single species [Ru(phbpy)(phen)(MeCN)]+ ([7]+) characterized by a doublet appearing at 9.88 ppm, while the doublet of the starting material at 10.49 ppm quantitatively disappeared. This photochemical behavior is comparable to the photosubstitution occurring in [Ru(tpy)(N–N)(X)]2+.31 In a similar fashion, the DMSO ligand in [1]PF6 and [3]PF6 could also be exchanged upon photoirradiation by deuterated acetonitrile to afford [Ru(phbpy)(bpy)(CD3CN)]+ ([6]+) and [Ru(phbpy)(dpq)(CD3CN)]+ ([8]+), respectively. However, [4]PF6 and [5]PF6 were not photosubstitutionally active, in contrast to the noncyclometalated analogons [Ru(tpy)(dppz)(SRR′)] and [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(SRR′)] (SRR′ = 2-(2-(2-(methylthio)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethyl-β-d-glucopyranoside)27 that both exchange their thioether ligand upon light irradiation.27

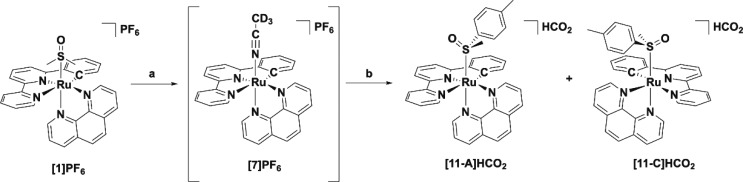

Scheme 3. Reagents and Conditions for the Synthesis of [11-A/C]HCO2.

(a) hv ≥ 410 nm in CD3CN. (b) i. (R)-Methyl p-tolylsulfoxide in MeOH, reflux, 16 h; ii. Reverse-phase HPLC (0.1% HCO2H in MeCN/H2O). (5% over two steps for [11-A]HCO2, 4% over two steps for [11-C]HCO2).

Figure 3.

Evolution of the 1H NMR spectra of [2]PF6 in CD3CN (3.0 mg in 0.6 mL) upon irradiation with white light (>410 nm) from a 1000 W xenon Arc lamp fitted with 400 nm cutoff filter 1 cm from the light source at T = 298 K. Spectra were taken every 1 h, with tirr = 7 h.

Resolving Diastereomers

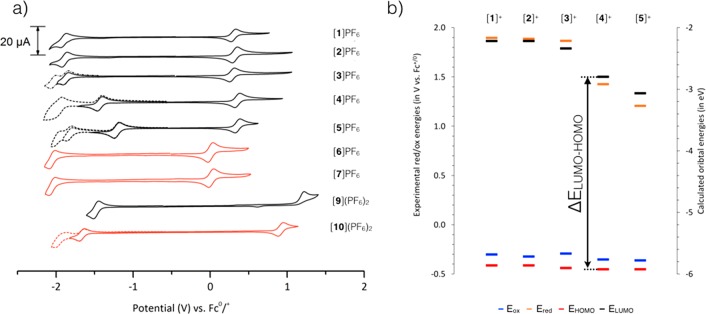

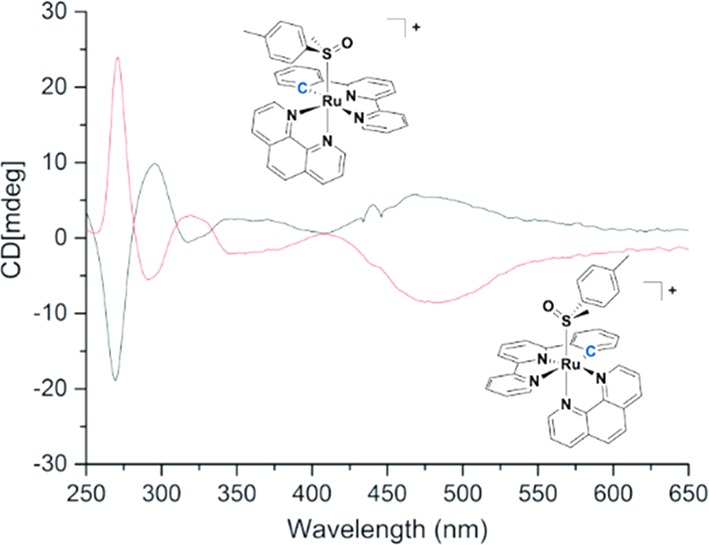

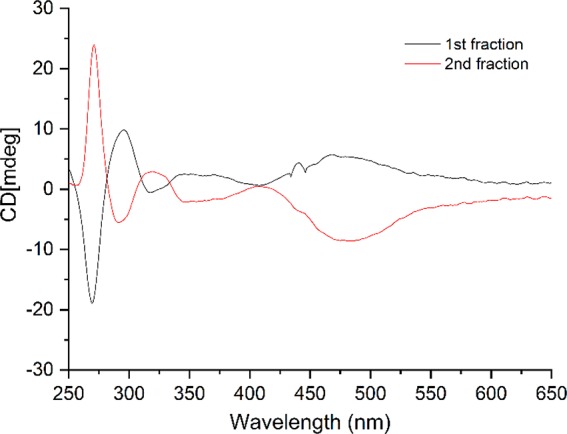

The photoactivity of [1]PF6–[3]PF6 therefore allowed us to investigate separation of their enantiomers. [2]PF6 was used as representative example. In a first attempt, [2]PF6 was converted to [7]PF6 using white light irradiation in deuterated acetonitrile (∼7 h). However, neither chiral HPLC nor crystallization using sodium (+)-tartrate allowed for resolving this intermediate. Instead, an alternative approach was used: racemic [7]PF6 was allowed to react with an excess of enantiomerically pure (R)-methyl p-tolylsulfoxide in MeOH, affording a (1:1) mixture of diastereomers of (anticlockwise/clockwise) A/C-[Ru(phbpy)(phen)(R)-Methyl p-tolylsulfoxide)]PF6, [11-A/C]HCO2 (Scheme 3). Subsequent purification over a reverse phase HPLC column afforded [11-A]HCO2 and [11-C]HCO2 as their respective diastereomers in 9% yield (5% over two steps for [11-A]HCO2 and 4% over two steps for [11-C]HCO2 (Figure S6). 1H NMR confirmed that fraction 1 corresponded to the R-C diastereomer, which is most apparent because of its more shielded α-proton of phen appearing at 10.64 ppm (Figure 4). Fraction 2 contained the R-A diastereomer, with a doublet appearing at 10.74 ppm (Figure 4). This deshielding effect on the α-proton on phen is most likely attributed to the interaction of the tolyl group with the bidentate ligand. This assumption was supported by NOESY experiments (Figure S8), which showed the absence of interaction between the methyl of the sulfoxide and phen, whereas a weak interaction was observed for [11-A]HCO2 (Figure S8). Both [11-A]HCO2 and [11-C]PF6 are diastereomers and not enantiomers, so that specific rotation would not give any valuable information on their chirality. Circular dichroism (CD) was used instead to demonstrate they are related to the two enantiomers [2-A]+ and [2-C]+. The CD spectra of [11-A]PF6 and [11-C]PF6 in MeCN (Figure 5) displayed symmetrical curves typical for enantiomers, except in the region below 250 nm where the contribution of the chiral (R)-tolylsulfoxide ligand to the absorption becomes non-negligible.32 Around 450 nm, either positive or negative Cotton effects were observed for [11-A]PF6 or [11-C]PF6, respectively, which must originate from the 1MLCT transitions. Theoretically, resolution of these complexes by performing blue light irradiation in acetonitrile may be tempting. However, photosubstitution is usually accompanied by racemization of the coordination sphere, so that thermal ligand substitution would be preferred.33 This was however not possible due to the exceptional thermal stability of the sulfoxide cyclometalated complexes (see above) that prevented thermal displacement of the chiral sulfoxide to obtain isolated enantiomers of [A-7]+, [C-7]+, [A-2]+, or [C-2]+. However, the mirrored CD spectra of the diastereoisomers [11-A]HCO2 and [11-C]HCO2 provided a clear proof of the opposite chirality of these complexes.

Figure 4.

1HNMR spectrum (850 MHz) of [11-C]PF6 (top) and [11-A]PF6 (bottom).

Figure 5.

Superposition of CD spectra of first fraction (black, [11-C]HCO2) and second fraction (red, [11-A]HCO2) eluted diastereoisomers. T = 293 K, c = 5 × 10–5 M in MeCN.

Photophysical and Photochemical Characterization

The difference in photoreactivity between [1]+–[3]+ and [4]+–[5]+ was not straightforward to understand, and therefore a full photophysical characterization of the five complexes was carried out. The electronic absorption spectra (Figure S1) of these complexes show that they have a considerable bathochromic shift (∼40 nm, Table 3) and a significant broadening of their 1MLCT band compared to [9]2+ (411 nm, Table 3). [4]+ and [5]+ have additional absorption bands around 370 and 410 nm, respectively. These are most likely π–π* transitions arising from the dppz and dppn ligand. The spectra of [6]+–[8]+ in acetonitrile also showed a shift of the 1MLCT band of ∼50 nm compared to [10]2+. This bathochromic shift is common for cyclometalated ruthenium complexes12,34 and is mostly ascribed to an increase in the energy of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO, t2g).12

Table 3. Lowest-Energy Absorption Maxima (λmax), Molar Absorption Coefficients at λmax (ε in M–1 cm–1), Photosubstitution Quantum Yields in Acetonitrile (Φ450) at 298 K, 1O2 Quantum Yields (ΦΔ) at 293 K, and Phosphorescence Quantum Yield (ΦP) for [1]PF6–[10](PF6)2.

| complex | formula | λmax (εmax in M–1 cm–1)a | λem (nm) | ΦΔb | ΦPb | Φ450 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1]PF6 | [Ru(phbpy)(bpy)(DMSO-κS)]PF6 | 476 (50 × 102) | 786 | 3.2 × 10–2 | 1.6 × 10–4 | 4.1 × 10–5 |

| [2]PF6 | [Ru(phbpy)(phen)(DMSO-κS)]PF6 | 450 (57 × 102) | 800 | 3.9 × 10–2 | 2.1 × 10–4 | 1.3 × 10–5 |

| [3]PF6 | [Ru(phbpy)(dpq)(DMSO-κS)]PF6 | 451 (83 × 102) | 787 | 1.1 × 10–1 | 2.1 × 10–4 | 2.2 × 10–5 |

| [4]PF6 | [Ru(phbpy)(dppz)(DMSO-κS)]PF6 | 450 (84 × 102) | 618 | 7.0 × 10–3 | 2.6 × 10–4 | <10–6 |

| [5]PF6 | [Ru(phbpy)(dppn)(DMSO-κS)]PF6 | 450 (75 × 102) | 672 | <10–3 | 8.4 × 10–5 | <10–6 |

| [6]PF6 | [Ru(phbpy)(bpy)(CD3CN)]PF6 | 525 (71 × 102) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| [7]PF6 | [Ru(phbpy)(phen)(CD3CN)]PF6 | 503 (63 × 102) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| [8]PF6 | [Ru(phbpy)(dpq)(CD3CN)]PF6 | 495 (119 × 102) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| [9](PF6)2 | [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(DMSO-κS)](PF6)2 | 411 (75 × 102) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 1.6 × 10–2 |

| [10](PF6)2 | [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(MeCN)](PF6)2 | 455 (91 × 102) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

In MeCN.

in CD3OD.

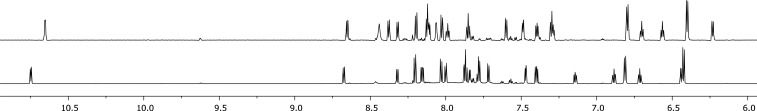

Visible light excitation of ruthenium polypyridyl complexes typically leads to (1) ligand exchange, (2) phosphorescence and/or, (3) singlet oxygen generation. First, the ability of [1]PF6–[5]PF6 to exchange the DMSO ligand for a solvent molecule was quantified by UV–vis spectroscopy (Figure 6). As observed under white light irradiation (>450 nm), monochromatic blue light irradiation in acetonitrile (450 nm) left [4]PF6 and [5]PF6 unaffected, while [1]PF6–[3]PF6 converted to the acetonitrile complexes [6]PF6–[8]PF6 with clear isosbestic points (441 and 490 nm for [1]PF6, 470 nm for [2]PF6, and 455 nm for [3]PF6) confirming the selectivity of the photoconversion. ESI-MS spectra taken after each reaction confirmed the formation of the acetonitrile photoproducts. The photosubstitution quantum yields (Φ450) were found to be 4.1 × 10–5 for [1]PF6, 1.3 × 10–5 for [2]PF6, and 2.2 × 10–5 for [3]PF6, which is a thousand times lower than that measured for [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(DMSO-κS)]2+(Φ450 = 1.6 × 10–2). This decreased reactivity is most likely caused by the destabilization of the 3MC state due to increased electron density at the metal center brought by the strong σ-donor C atom, whereas stabilization of the 3MLCT leads to a larger energy gap between the 3MLCT and 3MC state, therefore making thermal population of the latter rather unlikely.34 This interpretation is supported by previous work of the Turro group, who has demonstrated that the efficiency of the photosubstitution in sterically congested cyclometalated complexes is very low or absent.12,22

Figure 6.

Time evolution of the electronic absorption spectra of [1]PF6–[3]PF6 and [9](PF6)2 in deoxygenated MeCN upon irradiation at 450 nm at T = 298 K. Spectra measured every 30 min (every 0.5 min for [9]PF6). (a) [1](PF6) tirr = 16 h, [Ru]tot = 5.78 × 10–5 M, photon flux = 1.68 × 10–7 mol s–1. (b) [2](PF6), tirr = 23 h, [Ru]tot = 6.08 × 10–5 M, photon flux = 1.67 × 10–7 mol s–1. (c) [3]PF6, tirr = 16 h, [Ru]tot = 4.06 × 10–5 M, photon flux = 1.68 × 10–7 mol s–1. (d) [9](PF6)2, tirr = 1 h, [Ru]tot = 6.52 × 10–5 M, photon flux = 5.54 × 10–8 mol s–1.

Second, emission maxima (λem) and emission quantum yields (ΦP) for [1]PF6–[5]PF6 were measured in acetonitrile (Table 3). All compounds were found very weakly emissive with a slightly higher phosphorescence quantum yield compared to the polypyridyl complex [Ru(phbpy)(tpy)]+ (ΦP = 5 × 10–6).35 The emission wavelengths found for [1]+–[3]+ are comparable to those of [Ru(phbpy)(tpy)]+ (786–800 nm versus 797 nm)35 and are similar to complexes reported by the group of Turro and Sauvage.12,35 For complexes [4]+ and [5]+ a blue-shifted emission (618 and 672 nm) was observed compared to [Ru(phbpy)(tpy)]+, which suggested a different type of excited state compared to [1]+–[3]+. Third, singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ) were determined in deuterated methanol by measuring the emission of 1O2 at 1270 nm. ΦΔ values lower than 0.04 were found for all complexes with the exception of [3]PF6, which produced 1O2 with a photoefficiency (ΦΔ) of 0.11. Interestingly, [Ru(phbpy)(dppn)(DMSO-κS)]+ did not show any singlet oxygen production, whereas its noncyclometalated analogues [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(CD3OD)]2+ and [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(py)]2+ both have been demonstrated to be excellent 1O2 generators.36,37 Overall, changing terpyridine into phenylbipyridine had great consequences on the photochemical and photophysical properties of this series of complexes. Therefore, to further understand the photophysical differences between complexes [1]+–[3]+and [4]+–[5]+ electrochemical studies and DFT calculations were carried out.

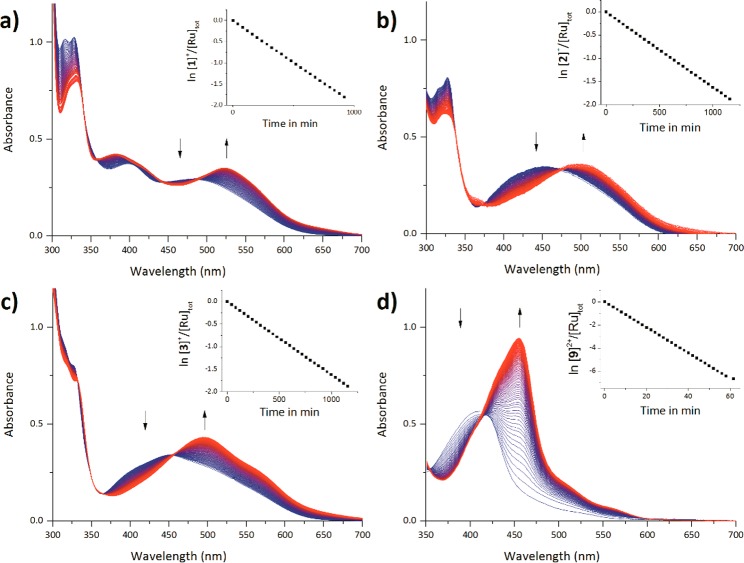

Electrochemistry and DFT

The electrochemical properties of complexes [1]PF6–[7]PF6 and [9](PF6)2–[10](PF6)2 were determined with cyclic voltammetry (Figure 7 and Table 4) to provide insight into the frontier orbitals of the cyclometalated complexes.38 As summarized in Table 4, the cyclometalated DMSO complexes [1]PF6–[5]PF6 show quasi-reversible oxidation processes (Ipa/Ipc ≈ 1) with RuIII/RuII couples near ∼+0.30 V vs Fc0/+ whereas [9](PF6)2 showed an irreversible RuII → RuIII oxidation at +1.23 V vs Fc0/+. Although the irreversibility of the oxidation of [9](PF6)2 does not strictly speaking allow to analyze this oxidation potential to a HOMO energy level, for [1]PF6–[5]PF6 the low-lying, reversible oxidation suggests that the Ru(dπ)-based HOMO of the cyclometalated complexes is very high in energy, due to the π-donating character of the phbpy– ligand.12 As the irreversibility of the oxidation of [9](PF6)2 is attributed to linkage isomerization of DMSO from S-bound to O-bound,39 cyclometalation also appears to prevents redox-induced linkage isomerization of the DMSO ligand, most likely due to the increased electron density on ruthenium. The quasi-reversible RuIII/II couple of the DMSO complexes [1]PF6–[2]PF6 also appeared at a higher potential (+0.30 V vs Fc0/+) compared to that of the acetonitrile compounds [6]PF6–[7]PF6 (0.00 V vs Fc0/+), which can be explained by the electronic effects of the monodentate ligand; κS-DMSO is a stronger π-acceptor than CD3CN and therefore has a stronger electron withdrawing effect on ruthenium(II).40 The ligand-based reductions for [1]PF6–[3]PF6 was found to have very similar energies, with quasi-reversible reductions around −2.0 V vs Fc+/0, suggesting that these are phbpy-based. For [4]PF6 and [5]PF6 however the L0/- appeared to occur at much less negative potentials (−1.4 V vs Fc+/0 for [4]PF6 and −1.2 V vs Fc+/0 for [5]PF6) due to the strong electron-accepting properties of the dipyridophenazine moieties. These first reductions being essentially reversible, the LUMO of these two complexes is dppz- or dppn-based, respectively.41 The experimental HOMO – LUMO gaps ΔEexp, which can be approximated, for quasi-reversible redox couples, to the difference between Eox and Ered (Figure 7, left), followed similar trends to the theoretical HOMO – LUMO gaps ΔEth calculated by DFT (Table 4). ΔEth were found very comparable indeed for complexes [1]PF6–[3]PF6 (ΔEexp ≈ 2.2 V and ΔEth ≈ 3.6 V) and much higher than that of [4]PF6 and [5]PF6 (ΔEexp = 1.8 and 1.6 V, respectively, and ΔEth = 3.13 and 1.86 V). The particularly low value of ΔE found for [4]PF6 and [5]PF6 suggested that the dppz and dppn ligands may generate low-lying excited states, which would explain the absence of photosubstitution with these two complexes.

Figure 7.

(a) Cyclic voltammograms of cyclometalated complexes [1]PF6–[7]PF6 and noncyclometalated complexes [9](PF6)2 and [10](PF6)2. Scan rate 100 mV s–1, with the exception of [4]PF6, [6]PF6, [7]PF6, and [9]PF6 which were measured at 200 mV s–1. L = DMSO-κS or CD3CN. (b) Experimental (Eox and Ered from cyclic voltammetry, in V vs. Fc+/0, left axis) and calculated (from DFT, in eV, right axis) values of the HOMO energy, LUMO energy, and ΔE energy gap.

Table 4. Electrochemical Properties As Measured with Cyclic Voltammetry and Theoretical HOMO – LUMO Gaps Calculated by DFTa.

| Eox (V) | Ipa/Ipc | Ered (V) | Ipc/Ipa | ΔEexp (V)c | ΔEth (eV)d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Ru(phbpy)(bpy)(DMSO-κS)]PF6 | [1]PF6 | +0.30 | 0.99 | –1.90 | 1.47 | 2.20 | 3.65 |

| [Ru(phbpy)(phen)(DMSO-κS)]PF6 | [2]PF6 | +0.32 | 1.02 | –1.89 | 1.11 | 2.21 | 3.65 |

| [Ru(phbpy)(dpq)(DMSO-κS)]PF6 | [3]PF6 | +0.29 | 1.01 | –1.87, −1.95 | 0.66, 2.23 | 2.16 | 3.57 |

| [Ru(phbpy)(dppz)(DMSO-κS)]PF6 | [4]PF6 | +0.35 | 1.04 | –1.43, −2.00 | 1.03 | 1.78 | 3.13 |

| [Ru(phbpy)(dppn)(DMSO-κS)]PF6 | [5]PF6 | +0.36 | 1.05 | –1.21, −1.82, −2.01 | 1.07, 1.52 | 1.57 | 2.86 |

| [Ru(phbpy)(bpy)(CD3CN)]PF6 | [6]PF6 | 0.00 | 1.00 | –2.05 | 1.34 | 2.05 | |

| [Ru(phbpy)(phen)(CD3CN)]PF6 | [7]PF6 | +0.02 | 1.04 | –2.05 | 1.38 | 2.07 | |

| [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(DMSO)](PF6)2 | [9](PF6)2 | +1.23b | –1.48 | 1.00 | 2.71 | ||

| [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(MeCN)](PF6)2 | [10](PF6)2 | +0.92 | 0.95 | –1.67 | 1.06 | 2.59 | 4.12 |

Potentials given vs. Fc0/Fc+ in MeCN with 0.1 M [Bu4N]PF6 as supporting electrolyte. Complexes were measured at 298 K with a scan rate of 100 mV s–1, with the exception of [4]PF6, [6]PF6 [7]PF6, and [9]PF6 which were measured at 200 mV s–1.

Epa.

ΔEth = ELUMO – EHOMO at the DFT/PBE0/TZP/COSMO level in water.

ΔEexp = Eox – Ered,.

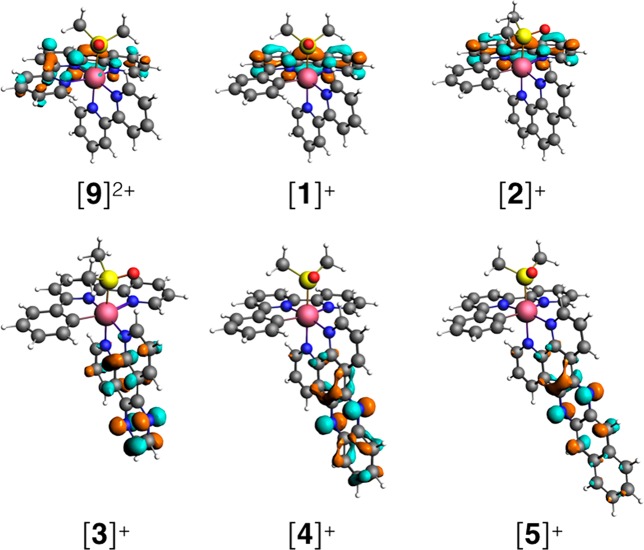

To confirm this hypothesis, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed for [1]+–[5]+ at the PBE0/TZP/COSMO level. The calculated HOMO energy, LUMO energy, and ΔEth = ELUMO – EHOMO of the minimized geometries followed the same trend as the experimental values (Table 4 and Figure 7b). For [1]+ and [2]+ the LUMO was located on the phbpy– ligand, for [4]+ and [5]+ it was localized on the dppz and dppn bidentate ligand, respectively (Figure S3–5), whereas for [3]+ empty orbitals localized both on phbpy– and dpq were found close in energy and near the LUMO level. Thus, like for the terpyridine series,41 extending the conjugation of the bidentate ligand in the cyclometalated series [1]+ to [5]+ resulted in a strong stabilization of the LUMO in [4]+ and [5]+, and in a shift of its localization, from the tridentate ligand in [1]+ and [2]+ to the bidentate ligand in [4]+ and [5]+, with [3]+ as borderline species (Figure 7b). The strong stabilization of the LUMO in [4]+ and [5]+ generates low-lying excited states, most likely of 3π–π* character.

Discussion

Recent examples of the group of Turro have shown that complexes such as cis-[Ru(phpy)(phen)(CH3CN)2]PF6 are as photoactive as their noncyclometalated counterparts, with a reported photosubstitution quantum yield (ΦP) of 0.25 in dichloromethane.22 A more recent report by Albani et al. has shown that for [Ru(biq)2(phpy)]PF6 the phpy– ligand increases the energy of the 3MC state, which in their case completely prevents photodissociation of the bidentate biq ligand.12 In the family of complexes [1]+–[5]+ presented here (Figure 8), cyclometalation of the terpyridine ligand allows photoinduced ligand exchange for three of the five complexes ([1]+–[3]+), while it is absent in the more conjugated analogues [4]+ and [5]+. The photoreactivity of ruthenium complexes is result of a delicate interplay of excited states of different natures and energies. In [1]+, [2]+, and [3]+ the emission maximum was close to 800 nm, irrespective of the nature of the bidentate ligand, because the 3MLCT excited states must be located on the phbpy ligand. By contrast, in the more conjugated complexes [4]+ and [5]+ the emission maxima depend significantly on the bidentate ligand, with a higher energy (λem = 618 nm) for the less conjugated dppz complex, compared to dppn (λem = 672 nm, see Table 3). Two results are apparently contradictory: the higher energy of the emitting (3MLCT) excited states vs the very low calculated and experimental ΔE values in [4]+ and [5]+, compared to [1]+, [2]+, and [3]+. This contradiction suggests that the lower triplet states centered on dppz and dppn and arising from the photochemical population of the low-lying LUMO-like orbitals are not emissive; they are probably of 3π–π* character and centered on the phenazine moiety of the dppz or dppn ligand. The weakly emissive states, on the other hand, most likely of 3MLCT character, are higher in energy in [4]+ and [5]+ because they are centered on the bpy moiety of dppz or dppn, while in [1]+, [2]+, and [3]+ they are centered on the more conjugated phenyl-functionalized bipyridine ligand. All in all, the ligand photosubstitution reactions occur from metal-centered 3MC states, which are high in energy for [1]+–[5]+ due to the excellent σ-donor properties of the cyclometalated ligand and probably poorly dependent on the conjugation of the bidentate ligand. Due to the presence of their low-lying 3π–π* states, [4]+ and [5]+ cannot perform any photosubstitution, as nonradiative decay pathways are faster.42 For [1]+, [2]+, and [3]+ these 3π–π* states are much higher in energy, so that the photogenerated, low-lying phbpy-based 3MLCT states, in spite of the higher-lying 3MC states, still leads to photosubstitution, though at a significantly lower rate than in the terpyridine analogue [9]2+.

Figure 8.

LUMO orbitals for [Ru(tpy)(bpy)L]2+ ([9]2+) and for [1]+–[5]+ at the DFT/PBE0/TZP/COSMO level in water.

Chiral-at-metal complexes based upon ruthenium, iridium, or rhodium have been extensively investigated by the group of Meggers,43−45 Barton,46 and others47−49 and have shown great promise in, e.g., asymmetric (photo)catalysis50,51 or as anticancer drugs.52 To resolve these types of complexes, a classical method consists of coordinating an enantiomerically pure chiral auxiliary to the metal center, resulting in a mixture of diastereomers which can be separated in preparative scales using normal phase chromatography such as silica.53 After separation, these diastereoisomers are typically treated with an achiral monodentate ligand of interest, thus resolving the two pure enantiomers. Other resolution methods involve direct recrystallization of enantiomers using chiral counterions such as Δ-TRISPHAT,32,54−56 or separation of the enantiomers on chiral HPLC.46 For [1]+–[5]+ these strategies could not be followed due on the one hand to the exceptional inertness of the coordination sphere and possibly to the very similar molecular shape of the cyclometalated vs. pyridyl side of the ruthenium-coordinated phbpy ligand. We hence relied on photochemical substitution to introduce a chiral sulfoxide ligand as resolving agent. The resulting diastereoisomeric ruthenium complexes [11-A]PF6 and [11-C]PF6 were inseparable on normal-phase silica. We therefore diverted to the use of reverse phase HPLC using 0.1% formic acid in the eluent. As a result, the isolation of the two diastereoisomers as their formate complexes was possible, but the presence of formic acid affected the overall yield (9%), most likely due to partial reprotonation of the cyclometalated ligand and subsequent (partial) degradation of the products. This is an issue that will be addressed in the future.

Conclusion

Replacing the terpyridine tridentate ligand in [Ru(tpy)(NN)L]2+ with phbpy has led to a new family of chiral-at-metal complexes [1]+–[5]+ with drastically altered thermal and photochemical properties compared to their polypyridine analogues. In particular, thermal substitution of the monodentate sulfoxide ligands becomes virtually impossible, while the ligand photosubstitution efficiency was reduced or even quenched due to the strong effect of cyclometalation on the energy of the HOMO and LUMO of the complexes. When N–N is a phenazine-based ligand ([4]+ or [5]+), the LUMO is based on the bidentate ligand and full quenching of the photoreactivity occurred, in great contrast to the photochemical behavior of terpyridine analogues such as [Ru(tpy)(dppz)(SRR’)]2+ or [Ru(tpy)(dppn)(SRR’)]2+ that undergo selective photosubstitution in water (Φ450 = 0.0227 and 0.00095,36 respectively). The resolution of photosubstitutionally and thermally inert chiral cyclometalated complexes such as [4]+ and [5]+ will thus require strategies that still need to be developed. However, when N–N is bpy, phen, or dpq ([1]+–[3]+), selective photosubstitution of DMSO by acetonitrile remained possible. The ability of [1]+–[3]+ to exchange DMSO by acetonitrile upon visible light irradiation can be exploited, as demonstrated here with [2]+, to labilize the thermally inert achiral DMSO ligand and replace it in two steps by a chiral sulfoxide ligand, thus allowing the separation of the two chiral isomers [11-A]+ and [11-C]+. This works demonstrates that photosubstitution reactions can be useful for the resolution of chiral-at-metal organometallic complexes, which opens new synthetic routes toward catalytically or biologically active chiral organometallic complexes.

Acknowledgments

NWO–CW (Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research) is kindly acknowledged for a VIDI grant to S.B. The European Research Council is kindly acknowledged for an ERC starting grant to S.B. The COST action CM1105 is acknowledged for stimulating scientific discussions. Dr. Jordi-Amat Cuello Garibo is kindly acknowledged for help with CD measurements. Prof. E. Bouwman is kindly acknowledged for support and scientific discussions.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.8b10264.

Synthetic procedures for the synthesis of [1]PF6-[8]PF6, [11-A/C]HCO2, [12]–[16]; quantum yield determination for [1]PF6, [2]PF6, [3]PF6, and [9]PF6; NMR irradiation experiments for [1]PF6–[3]PF6; electrochemistry experiments; CD spectra for [11-A/C]HCO2; DFT structures for [1]PF6–[5]PF6; and the NOESY spectrum of [11-A]HCO2 (PDF)

CIF files for the studied compounds (ZIP)

Author Contributions

§ These authors made an equal contribution to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Murray B. S.; Babak M. V.; Hartinger C. G.; Dyson P. J. The development of RAPTA compounds for the treatment of tumors. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 306, 86–114. 10.1016/j.ccr.2015.06.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dougan S. J.; Sadler P. J. The design of organometallic ruthenium arene anticancer agents. Chimia 2007, 61 (11), 704–715. 10.2533/chimia.2007.704. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pena B.; David A.; Pavani C.; Baptista M. S.; Pellois J. P.; Turro C.; Dunbar K. R. Cytotoxicity Studies of Cyclometallated Ruthenium(II) Compounds: New Applications for Ruthenium Dyes. Organometallics 2014, 33 (5), 1100–1103. 10.1021/om500001h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mari C.; Pierroz V.; Rubbiani R.; Patra M.; Hess J.; Spingler B.; Oehninger L.; Schur J.; Ott I.; Salassa L.; Ferrari S.; Gasser G. DNA intercalating Ru(II) polypyridyl complexes as effective photosensitizers in photodynamic therapy. Chem. - Eur. J. 2014, 20 (44), 14421–36. 10.1002/chem.201402796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachter E.; Heidary D. K.; Howerton B. S.; Parkin S.; Glazer E. C. Light-activated ruthenium complexes photobind DNA and are cytotoxic in the photodynamic therapy window. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48 (77), 9649–51. 10.1039/c2cc33359g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan H.; Ghrayche J. B.; Wei J.; Renfrew A. K. Photolabile Ruthenium (II)–Purine Complexes: Phototoxicity, DNA Binding, and Light-Triggered Drug Release. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 2017 (12), 1679–1686. 10.1002/ejic.201601137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burke C. S.; Byrne A.; Keyes T. E. Highly Selective Mitochondrial Targeting by a Ruthenium(II) Peptide Conjugate: Imaging and Photoinduced Damage of Mitochondrial DNA. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57 (38), 12420–12424. 10.1002/anie.201806002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke C. S.; Byrne A.; Keyes T. E. Targeting Photoinduced DNA Destruction by Ru(II) Tetraazaphenanthrene in Live Cells by Signal Peptide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (22), 6945–6955. 10.1021/jacs.8b02711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huisman M.; White J. K.; Lewalski V. G.; Podgorski I.; Turro C.; Kodanko J. J. Caging the uncageable: using metal complex release for photochemical control over irreversible inhibition. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52 (85), 12590–12593. 10.1039/C6CC07083C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A.; Yadav R.; White J. K.; Herroon M. K.; Callahan B. P.; Podgorski I.; Turro C.; Scott E. E.; Kodanko J. J. Illuminating cytochrome P450 binding: Ru(ii)-caged inhibitors of CYP17A1. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53 (26), 3673–3676. 10.1039/C7CC01459G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albani B. A.; Pena B.; Leed N. A.; de Paula N. A.; Pavani C.; Baptista M. S.; Dunbar K. R.; Turro C. Marked improvement in photoinduced cell death by a new tris-heteroleptic complex with dual action: singlet oxygen sensitization and ligand dissociation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136 (49), 17095–101. 10.1021/ja508272h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albani B. A.; Pena B.; Dunbar K. R.; Turro C. New cyclometallated Ru(II) complex for potential application in photochemotherapy?. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2014, 13 (2), 272–80. 10.1039/C3PP50327E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyva L.; Sirlin C.; Rubio L.; Franco C.; Le Lagadec R.; Spencer J.; Bischoff P.; Gaiddon C.; Loeffler J. P.; Pfeffer M. Synthesis of cycloruthenated compounds as potential anticancer agents. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 2007 (19), 3055–3066. 10.1002/ejic.200601149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Ji L. N.; Mei W. J. The development of ruthenium complexes as anticancer drugs activation and anticancer mechanism. PROG CHEM 2004, 16 (6), 969–974. [Google Scholar]

- Kreitner C.; Erdmann E.; Seidel W. W.; Heinze K. Understanding the Excited State Behavior of Cyclometalated Bis(tridentate)ruthenium(II) Complexes: A Combined Experimental and Theoretical Study. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54 (23), 11088–11104. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b01151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreitner C.; Heinze K. The photochemistry of mono- and dinuclear cyclometalated bis(tridentate)ruthenium(II) complexes: dual excited state deactivation and dual emission. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45 (13), 5640–58. 10.1039/C6DT00384B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreitner C.; Heinze K. Excited state decay of cyclometalated polypyridine ruthenium complexes: insight from theory and experiment. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45 (35), 13631–47. 10.1039/C6DT01989G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.; Zhang P.; Chen H.; Ji L.; Chao H. Comparison between polypyridyl and cyclometalated ruthenium(II) complexes: anticancer activities against 2D and 3D cancer models. Chem. - Eur. J. 2015, 21 (2), 715–25. 10.1002/chem.201404922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatzschneider U.; Niesel J.; Ott I.; Gust R.; Alborzinia H.; Wolfl S. Cellular uptake, cytotoxicity, and metabolic profiling of human cancer cells treated with ruthenium(II) polypyridyl complexes [Ru(bpy)2(N--N)]Cl2 with N--N = bpy, phen, dpq, dppz, and dppn. ChemMedChem 2008, 3 (7), 1104–9. 10.1002/cmdc.200800039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mari C.; Pierroz V.; Ferrari S.; Gasser G. Combination of Ru(ii) complexes and light: new frontiers in cancer therapy. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6 (5), 2660–2686. 10.1039/C4SC03759F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funaki T.; Yanagida M.; Onozawa-Komatsuzaki N.; Kasuga K.; Kawanishi Y.; Kurashige M.; Sayama K.; Sugihara H. Synthesis of a new class of cyclometallated ruthenium(II) complexes and their application in dye-sensitized solar cells. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2009, 12 (9), 842–845. 10.1016/j.inoche.2009.06.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer A. M.; Pena B.; Sears R. B.; Chen O.; El Ojaimi M.; Thummel R. P.; Dunbar K. R.; Turro C. Cytotoxicity of cyclometallated ruthenium complexes: the role of ligand exchange on the activity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc., A 2013, 371 (1995), 20120135. 10.1098/rsta.2012.0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z.; Gong L.; Celik M. A.; Harms K.; Frenking G.; Meggers E. Asymmetric coordination chemistry by chiral-auxiliary-mediated dynamic resolution under thermodynamic control. Chem. - Asian J. 2011, 6 (2), 474–81. 10.1002/asia.201000555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong L.; Mulcahy S. P.; Harms K.; Meggers E. Chiral-auxiliary-mediated asymmetric synthesis of tris-heteroleptic ruthenium polypyridyl complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131 (28), 9602–3. 10.1021/ja9031665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong L.; Wenzel M.; Meggers E. Chiral-auxiliary-mediated asymmetric synthesis of ruthenium polypyridyl complexes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46 (11), 2635–44. 10.1021/ar400083u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryabov A. D.; Le Lagadec R.; Estevez H.; Toscano R. A.; Hernandez S.; Alexandrova L.; Kurova V. S.; Fischer A.; Sirlin C.; Pfeffer M. Synthesis, characterization, and electrochemistry of biorelevant photosensitive low-potential orthometalated ruthenium complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44 (5), 1626–34. 10.1021/ic048270w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lameijer L. N.; Breve T. G.; van Rixel V. H. S.; Askes S. H. C.; Siegler M. A.; Bonnet S. Effects of the Bidentate Ligand on the Photophysical Properties, Cellular Uptake, and (Photo)cytotoxicity of Glycoconjugates Based on the [Ru(tpy)(NN)(L)](2+) Scaffold. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24 (11), 2709–2717. 10.1002/chem.201705388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rack J. J.; Winkler J. R.; Gray H. B. Phototriggered Ru(II)-dimethylsulfoxide linkage isomerization in crystals and films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123 (10), 2432–3. 10.1021/ja000179d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachford A. A.; Petersen J. L.; Rack J. J. Designing molecular bistability in ruthenium dimethyl sulfoxide complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44 (22), 8065–75. 10.1021/ic050778r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet S.; Collin J. P.; Gruber N.; Sauvage J. P.; Schofield E. R. Photochemical and thermal synthesis and characterization of polypyridine ruthenium(II) complexes containing different monodentate ligands. Dalton Trans. 2003, 24, 4654–4662. 10.1039/b310198c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbach R. E.; Rodriguez-Garcia I.; van Lenthe J. H.; Siegler M. A.; Bonnet S. N-acetylmethionine and biotin as photocleavable protective groups for ruthenium polypyridyl complexes. Chem. - Eur. J. 2011, 17 (36), 9924–9. 10.1002/chem.201101541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laleu B.; Mobian P.; Herse C.; Laursen B. W.; Hopfgartner G.; Bernardinelli G.; Lacour J. Resolution of [4]heterohelicenium dyes with unprecedented Pummerer-like chemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44 (12), 1879–83. 10.1002/anie.200462321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottle A. J.; Alary F.; Boggio-Pasqua M.; Dixon I. M.; Heully J. L.; Bahreman A.; Askes S. H.; Bonnet S. Pivotal Role of a Pentacoordinate (3)MC State on the Photocleavage Efficiency of a Thioether Ligand in Ruthenium(II) Complexes: A Theoretical Mechanistic Study. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55 (9), 4448–56. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b00268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barigelletti F.; Ventura B.; Collin J. P.; Kayhanian R.; Gavina P.; Sauvage J. P. Electrochemical and spectroscopic properties of cyclometallated and non-cyclometallated ruthenium(II) complexes containing sterically hindering ligands of the phenanthroline and terpyridine families. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2000, 2000 (1), 113–119. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collin J. P.; Beley M.; Sauvage J. P.; Barigelletti F. A Room-Temperature Luminescent Cyclometallated Ruthenium(Ii) Complex of 6-Phenyl-2,2’-Bipyridine. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1991, 186 (1), 91–93. 10.1016/S0020-1693(00)87936-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lameijer L. N.; Hopkins S. L.; Breve T. G.; Askes S. H.; Bonnet S. d- Versus l-Glucose Conjugation: Mitochondrial Targeting of a Light-Activated Dual-Mode-of-Action Ruthenium-Based Anticancer Prodrug. Chem. - Eur. J. 2016, 22 (51), 18484–18491. 10.1002/chem.201603066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoll J. D.; Albani B. A.; Durr C. B.; Turro C. Unusually efficient pyridine photodissociation from Ru(II) complexes with sterically bulky bidentate ancillary ligands. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118 (45), 10603–10. 10.1021/jp5057732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang H. J.; Hopkins S. L.; Siegler M. A.; Bonnet S. Frontier orbitals of photosubstitutionally active ruthenium complexes: an experimental study of the spectator ligands’ electronic properties influence on photoreactivity. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46 (30), 9969–9980. 10.1039/C7DT01540B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rack J. J.; Rachford A. A.; Shelker A. M. Turning off phototriggered linkage isomerizations in ruthenium dimethyl sulfoxide complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 42 (23), 7357–9. 10.1021/ic034918d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxon S. P.; Metcalfe C.; Adams H.; Webb M.; Thomas J. A. Electrochemical and photophysical properties of DNA metallo-intercalators containing the ruthenium(II) tris(1-pyrazolyl)methane unit. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46 (2), 409–16. 10.1021/ic0607134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White T. A.; Maji S.; Ott S. Mechanistic insights into electrocatalytic CO 2 reduction within [Ru II (tpy)(NN) X] n+ architectures. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43 (40), 15028–15037. 10.1039/C4DT01591F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoll J. D.; Albani B. A.; Turro C. New Ru(II) complexes for dual photoreactivity: ligand exchange and (1)O2 generation. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48 (8), 2280–7. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo H.; Shen X.; Wang C.; Zhang L.; Rose P.; Chen L. A.; Harms K.; Marsch M.; Hilt G.; Meggers E. Asymmetric photoredox transition-metal catalysis activated by visible light. Nature 2014, 515 (7525), 100–3. 10.1038/nature13892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Y.; Yuan W.; Gong L.; Meggers E. Aerobic Asymmetric Dehydrogenative Cross-Coupling between Two C(sp3)-H Groups Catalyzed by a Chiral-at-Metal Rhodium Complex. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54 (44), 13045–8. 10.1002/anie.201506273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meggers E. Asymmetric Synthesis of Octahedral Coordination Complexes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 2011 (19), 2911–2926. 10.1002/ejic.201100327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle K. M.; Barton J. K. A Family of Rhodium Complexes with Selective Toxicity toward Mismatch Repair-Deficient Cancers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (16), 5612–5624. 10.1021/jacs.8b02271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. Z.; Wen A. H.; Yao S. Y.; Ye B. H. Enantioselective syntheses of sulfoxides in octahedral ruthenium(II) complexes via a chiral-at-metal strategy. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54 (6), 2726–33. 10.1021/ic502898e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesek D.; Inoue Y.; Ishida H.; Everitt S. R. L.; Drew M. G. B. The first asymmetric synthesis of chiral ruthenium tris(bipyridine) from racemic ruthenium bis(bipyridine) complexes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41 (15), 2617–2620. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)00230-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hesek D.; Inoue Y.; Everitt S. R. L.; Ishida H.; Kunieda M.; Drew M. G. B. Conversion of a new chiral reagent Δ-[Ru(bpy)2 (dmso)Cl]PF6 to Δ-[Ru(bpy)2(dmbpy)]PF6Cl with 96.8% retention of chirality (dmbpy = 4,4′-dimethyl-2,2′-bipyridine). Chem. Commun. 1999, (5), 403–404. 10.1039/a809698h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huo H.; Fu C.; Harms K.; Meggers E. Asymmetric catalysis with substitutionally labile yet stereochemically stable chiral-at-metal iridium(III) complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136 (8), 2990–3. 10.1021/ja4132505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J.; Shen X.; Harms K.; Meggers E. Expanding the family of bis-cyclometalated chiral-at-metal rhodium(iii) catalysts with a benzothiazole derivative. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45 (20), 8320–3. 10.1039/C6DT01063F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Huang H.; Zhang Q.; Zhang P. Chirality in metal-based anticancer agents. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47 (12), 4017–4026. 10.1039/C8DT00089A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms M.; Lin Z. J.; Gong L.; Harms K.; Meggers E. Method for the Preparation of Nonracemic Bis-Cyclometalated Iridium(III) Complexes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 2013 (24), 4164–4172. 10.1002/ejic.201300411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lacour J.; Ginglinger C.; Grivet C.; Bernardinelli G. Synthesis and Resolution of the Configurationally Stable Tris(tetrachlorobenzenediolato)phosphate(V) Ion. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1997, 36 (6), 608–610. 10.1002/anie.199706081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lacour J.; Jodry J. J.; Ginglinger C.; Torche-Haldimann S. Diastereoselective Ion Pairing of TRISPHAT Anions and Tris(4,4′-dimethyl-2,2′-bipyridine)iron(II). Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998, 37 (17), 2379–2380. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacour J.; Goujon-Ginglinger C.; Torche-Haldimann S.; Jodry J. Efficient Enantioselective Extraction of Tris(diimine)ruthenium(II) Complexes by Chiral, Lipophilic TRISPHAT Anions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000, 39 (20), 3695–3697. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.