Abstract

We report the design, synthesis, and evaluation of novel 5-fluorouracil (5FU) prodrugs 1a,1b that are efficiently activated by the high level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cancer cells. Prodrugs 1a,1b selectively kill cancer cells over normal cells and are well-tolerated in mice. The strategy described herein can extend application of chemotherapeutic drugs.

Keywords: 5-Fluorouracil, prodrugs, reactive oxygen species, anticancer

The FDA-approved chemotherapy drug 5-fluorouracil (5FU, Figure 1) was first introduced by Heidelberger et al. in 1957 as an antineoplastic antimetabolite of the uracil anabolic pathway.1 In the human body, 5FU interferes with DNA synthesis by blocking the activity of the nucleotide synthesis enzyme thymidylate synthase (TS), which catalyzes the conversion of deoxyuridylic acid to thymidylic acid.2 As a single agent or in combination with other chemotherapeutics, 5FU has been widely prescribed for a variety of solid tumors including breast cancer, colorectal cancer, stomach cancer, pancreatic cancer, and cervical cancer by injection and skin cancer as a cream. While remarkably benefiting cancer patients, 5FU also possesses major side effects such as myelosuppression, central neurotoxicity, and gastrointestinal toxicity.3 Moreover, 5FU is metabolically unstable with the majority of the dose converted to 3-fluoroalanine by the pyrimidine degrading enzyme dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD).4

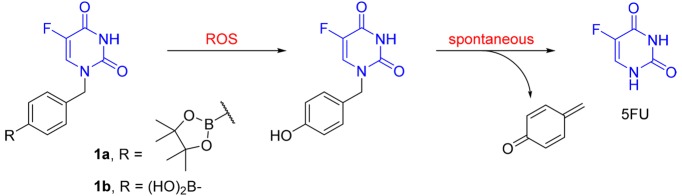

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of 5FU and clinically used 5FU-prodrugs.

To overcome the limitation of 5FU, prodrug strategies have been actively pursued. Among numerous small molecule 5FU-prodrugs described in the literature,5 four have been successfully used in the clinic, including tegafur, doxifluridine, carmofur, and capecitabine (Figure 1). These compounds are orally available and activated in the human body via different mechanisms. Activation of tegafur involves either a 5′-hydroxylation catalyzed by the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP2A66 or an enzymatic cleavage of the N1–C2′ bond of the molecule.7 Doxifluridine is a second-generation of nucleotide-based prodrug of 5FU that has been approved in several Asian countries.8 Its activation in tumors is achieved by either thymidine phosphorylase9 or pyrimidine-nucleoside phosphorylase.10 The lipophilic 5FU analogue carmofur overcomes the problem of 5FU degradation by DPD.11 The carbamoyl group of carmofur is enzymatically removed in the human body to release 5FU. Finally, capecitabine is another carbamate-based 5FU-prodrug that is activated in the liver and cancer cells through sequential reactions catalyzed by carboxylesterase and cytidine deaminase.12

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), the metabolic byproducts of oxygen metabolism, play an important role in maintaining cellular redox homeostasis. Unlike the normal cell environment where the ROS level is controlled by balancing its production and elimination, cancer cells exhibit enhanced levels of ROS such as superoxide (O2•–),13 hydrogen peroxide (H2O2),14 and hydroxyl radical (HO•)15 due to increased metabolic activities and mitochondrial malfunction. It has been shown that high levels of ROS in cancer cells are also associated with DNA mutations that lead to tumor angiogenesis16 and metastasis17 and drug resistance.18 At the same time, the growth and transformation of cancer cells are promoted with the condition of a modest rise of intracellular ROS.19

While ROS themselves have been exploited for the development of tumor-selective therapeutics by amplifying oxidative stress,20−22 ROS-activated prodrugs have also been developed to obtain tumor selective agents.23,24 As commonly used bioprecursors, arylboronic acids and esters have been widely employed as specific ROS-activated groups for various drugs including SAHA,25 aminopterin and methotrexate,26 SN-38,27 nitrogen mustards,28,29 nitric oxide donors,30,31 aminoferrocene,32−34 and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) inhibitors.35 To the best of our knowledge, a similar strategy has not been described for 5FU.

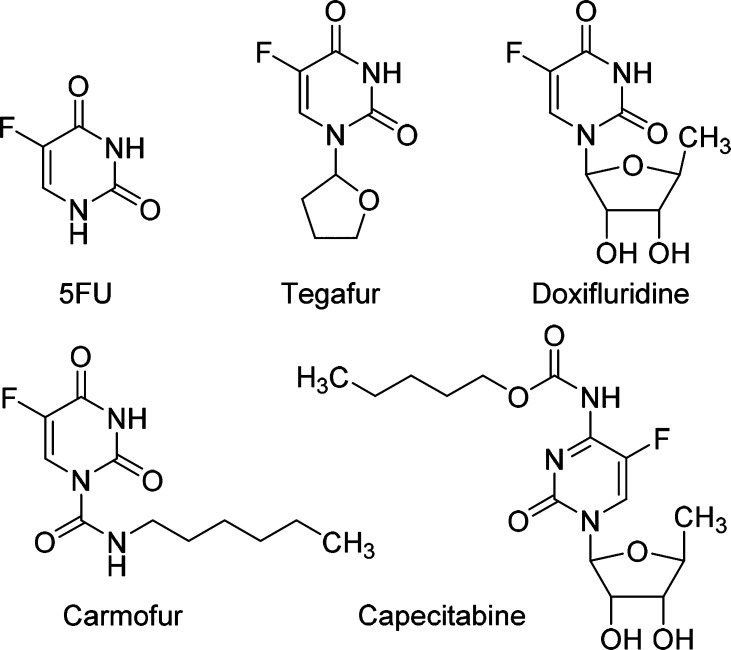

Herein we report the design and evaluation of novel arylboronate-based prodrugs 1a,1b of 5FU (Figure 2). The p-boronate-benzyl group was introduced to the N1 position to limit the metabolic degradation by DPD. The arylboronate groups are designed as ROS-sensitive triggers, which react with H2O2 to generate the corresponding phenol intermediate. Spontaneous breakdown of this intermediate will release 5FU, along with a highly reactive byproduct 4-methylenecyclohexa-2,5-dien-1-one, which is rapidly hydrolyzed in aqueous environment to give the nontoxic 4-(hydroxymethyl)phenol.36

Figure 2.

ROS-activated 5FU prodrugs 1a,1b.

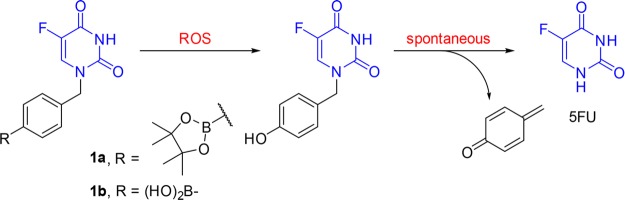

The synthesis of prodrugs 1a,1b and a control compound 1c is detailed in Scheme 1. The N1-selective benzylation of 5FU using either compound 2 or compound 3 in the presence of 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) as the base generated phenylboronate ester 1a and control 1c in modest yields. Then compound 1a was treated with NaIO4 in the presence of NH4OAc to yield compound 1b in modest yields.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Compounds 1a–1c.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 5FU, DBU, DMF, rt, 12 h, 37% for 1a and 49% for 1c; (b) NaIO4, NH4OAc, rt, 16 h, 69%.

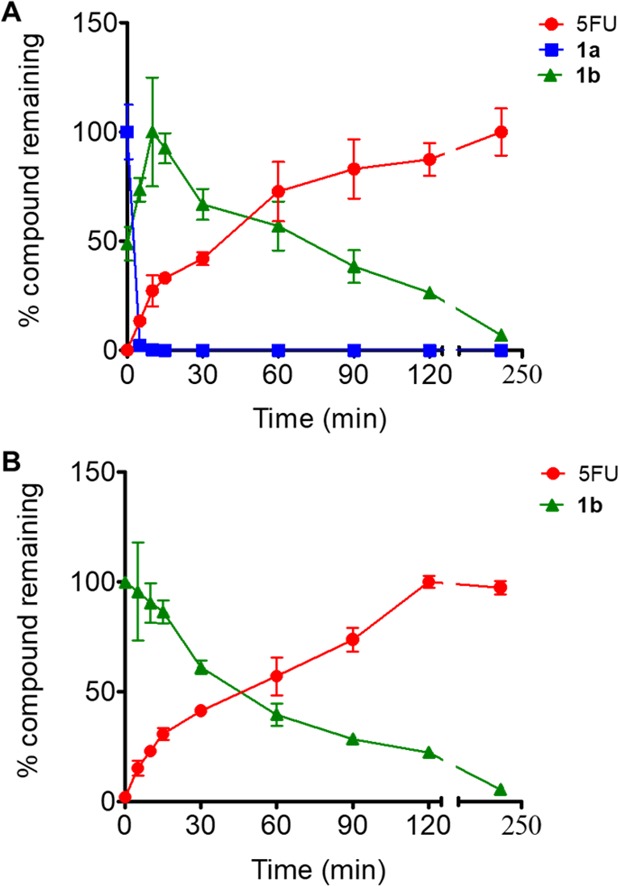

We first tested the efficiency of new prodrugs 1a,1b in releasing the parent drug 5FU in the presence of the ROS H2O2 (Figure 3). Compounds 1a,1b were incubated in a mixture of DMSO in PBS buffer (30%) with the addition of H2O2 (5 equiv) at 37 °C. The conversion of prodrugs 1a,1b and the production of 5FU were followed using RP-UPLC-MS. Both prodrugs were activated efficiently by H2O2 to release 5FU. Interestingly, under the assay conditions, the boronic ester 1a hydrolyzed rapidly to generate boronic acid 1b (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Release of 5FU from compounds 1a,1b. The incubation of each prodrugs (100 μM) was carried out in the presence of 5 equiv of H2O2: (A) prodrug 1a and (B) 1b. The conversion of prodrugs 1a,1b and release of 5FU was determined. The data represent mean ± SD of triplicates.

Next, we studied the anticancer effects of compounds 1a,1b against 60 human cancer cell lines (the Developmental Therapeutics Program of NCI). The cell lines were derived from different cancer types including leukemia, nonsmall-cell lung cancer, colon cancer, CNS cancer, melanoma, ovarian cancer, renal cancer, prostate cancer, and breast cancer (Supporting Information (SI), Table S1). The assay protocol can be found at: https://dtp.cancer.gov/default.htm. Compound 1a caused over 50% growth inhibition for most of the tested cell lines. In particular, it exhibited the most significant inhibition (81–96%) against the lung cancer NCI-H522 cells, melanoma MDA-MB-435 cells, ovarian cancer OVCAR-3 cells, and breast cancer MCF7 and MDA-MB-468 cells (Table 1). In general, boronic ester 1a demonstrated larger effects than the boronic acid analogue 1b (SI, Table S1). We reasoned that the differences in anticancer effects between compounds 1a,1b may be due to the more favorable membrane permeability of the boronic ester 1a.

Table 1. Anticancer Effects of Compounds 1a,1b.

| inhibition (%)a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| tumor type | cell line | 1a | 1b |

| lung cancer | NCI-H522 | 90 | 44 |

| melanoma | MDA-MB-435 | 96 | 65 |

| ovarian cancer | OVCAR-3 | 95 | 30 |

| breast cancer | MCF7 | 81 | 33 |

| MDA-MB-468 | 87 | 22 | |

Each cell line was treated with either compound 1a or compound 1b at the concentration of 50 μM for a period of 48 h. Then the growth inhibition (%) values were determined.

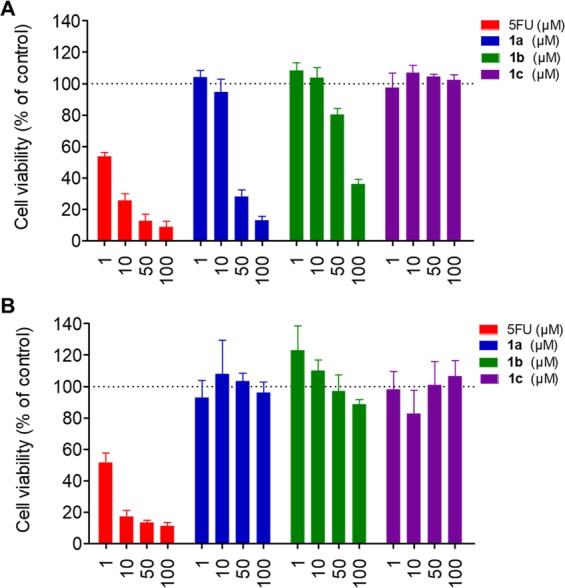

We further evaluated the anticancer effects of compounds 1a,1b in detail using the breast cancer MCF7 cells and normal MEC1 cells (Figure 4). Compound 1a exerted potent but lower antiproliferative activity as compared to 5FU, while compound 1b indicated much weaker effects. We reasoned that the decreased anticancer effects of the prodrugs may be due to the diminished cell membrane permeability. Cellular uptake of 5FU is facilitated by organic anion transporter 2 (OAT2) and reduced folate carrier 1 (RFC1),37 which would probably not contribute to the penetration of compounds 1a,1b. On the other hand, compared to 5FU, both prodrugs 1a,1b demonstrated no toxicity toward the normal MEC1 cells (cell viability >95%) at concentrations up to 100 μM. These differential killing results highlight the specificity of the new prodrugs 1a,1b for cancer cells over normal cells. Moreover, the control compound 1c, without the ROS-reactive group in its structure, exhibited no obvious antiproliferative effects against the MCF7 cells, indicating that prodrugs 1a,1b achieved their anticancer effects through the reactivity of the boronic acid or ester groups toward the ROS. To further verify the role of ROS in the drug release process, we performed the MTT assays using MCF7 cells pretreated with the ROS scavenger N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC). Upon pretreatment of NAC, the anticancer effects of prodrugs 1a,1b decreased significantly (SI, Figure S1), confirming that the new prodrugs exerted their cytotoxicity depending on ROS activation.

Figure 4.

Anticancer effects and selectivity of 5FU and compounds 1a–1c. Cell viability was analyzed after the breast cancer MCF7 cells (A), and normal MEC1 cells (B) were treated with 5FU or compounds 1a–1c at different concentrations. Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 4.

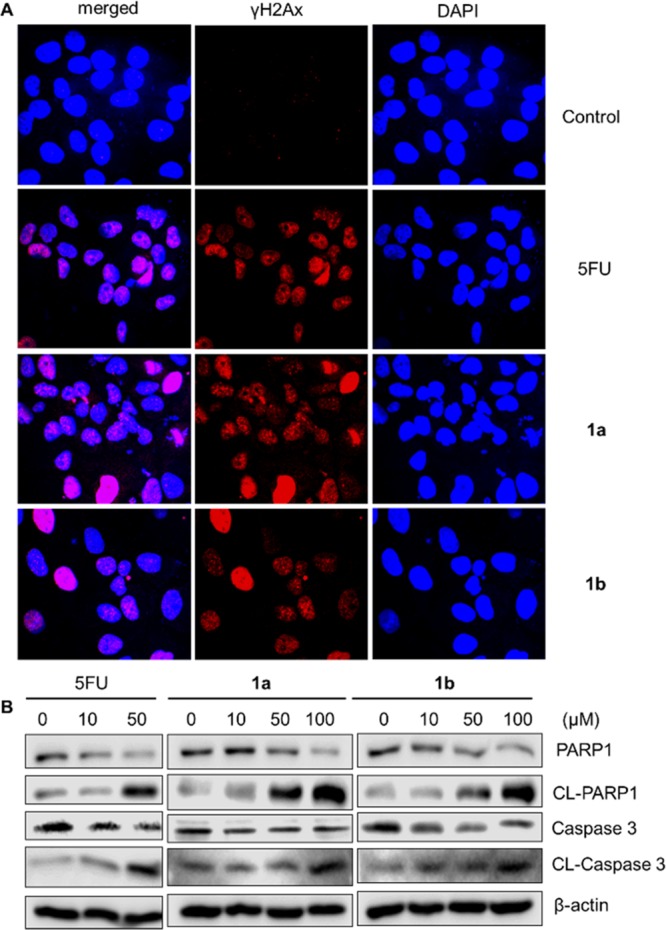

To understand the mechanism of action for prodrugs 1a,1b, we examined the impact of the treatment of compounds 1a,1b on γH2AX formation in MCF7 cells using an immunofluorescence assay. The γH2AX formation is a sensitive marker to visualize and quantify DNA double-strand breaks and the consequential cell apoptosis.38,39 As shown in Figure 5A, upon treatment of compounds 1a,1b, the cells showed dramatical increases in γH2AX formation, which was consistent with the effect of their parent 5FU. In addition, we also evaluated the effects of prodrugs 1a,1b on the PARP1 and caspase 3 cleavage in MCF7 cells using Western blots assays (Figure 5B). Activation of PARP1 and caspase 3, through cleavage, leads to cell apoptosis.40,41 Compared to vehicle-treated cells, treatment of prodrugs 1a,1b, similar to 5FU, reduced the levels of both PARP1 and caspase 3 in MCF7 cells. Interestingly, the same treatments of compounds 1a,1b, similar to that of 5FU, significantly increased the levels of cleaved PARP1 (CL-PARP1) and cleaved caspase 3 (CL-caspase 3) in MCF7 cells, as compared with those in the vehicle-treated controls. Therefore, prodrugs 1a,1b, similar to 5FU, can induce MCF7 cell apoptosis, which might contribute to their pharmacological actions.

Figure 5.

Effects of compounds 1a,1b in causing cell apoptosis. (A) Immunofluorescence of DNA cleavage protein γH2Ax was enhanced by using 5FU and prodrugs 1a,1b. (B) Immunoblot analysis of MCF-7 cells treated with 5FU, prodrugs 1a,1b for apoptosis markers PARP1, and caspase 3. The cells were treated for 48 h with the indicated concentrations of the compounds.

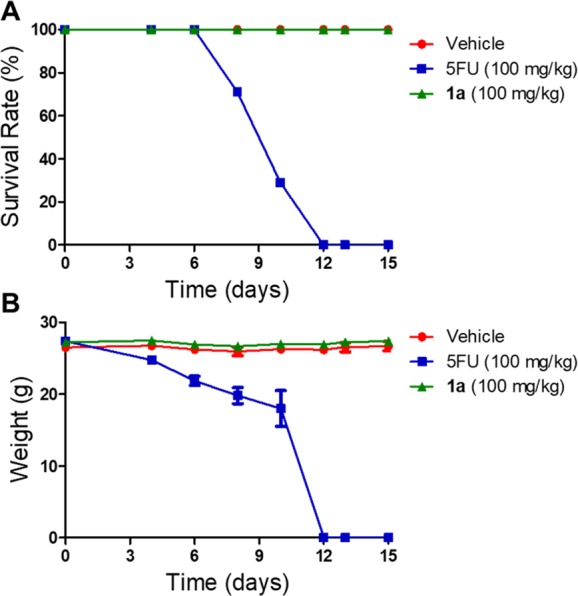

To evaluate the safety profile of the new prodrugs, we tested the acute toxicity of compound 1a in wild-type C57BL/6 male mice (Figure 6). While treatment with a high dose (100 mg/kg) of 5FU killed all mice on the twelfth day (Figure 6A), the same dose of compound 1a did not cause animal death or abnormality in eating, drinking, or activity throughout the period. While body weights of the mice in the 5FU treated group significantly decreased as compared to those of the vehicle group, no obvious changes were observed in the prodrug 1a treated group (Figure 6B). These results indicate that, compared with the parent 5FU, prodrug 1a had more favorable drug safety, exhibiting reduced toxicity in normal tissues. This prodrug would benefit further research on its potential as an effective targeted therapy.

Figure 6.

Survival rate (A) and body weight (B) curves of the mice received vehicle, 5FU, or 1a. The 21 mice were randomly distributed into three groups (seven mice in each group): vehicle (5% DMSO and 15% polyethylene glycol in saline), 100 mg/kg of 5FU, and 100 mg/kg of prodrug 1a. Mice were treated every other day by intraperitoneal (ip) injection for 15 days, and the survival and body weights of the mice were recorded during the treatment.

In conclusion, we have designed, synthesized, and evaluated novel arylboronate-based 5FU prodrugs 1a,1b. These prodrugs are activated by high levels of ROS in cancer cells and efficiently release 5FU. Prodrugs 1a,1b exhibited high specificity for cancer cells over normal cells. Furthermore, prodrug 1a demonstrated a more favorable safety profile as compared to parent 5FU. These findings suggest that ROS-activated prodrugs offer an effective way to improve the therapeutic effectiveness and selectivity of current anticancer chemotherapeutic agents.

Acknowledgments

We thank the American Association for Cancer Research grant 00167155 to F.X., the Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation, and the Leukemia Lymphoma Society for grant to F.X. The National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) supported the research by Y.S. [R01GM099742]. Y.S. is a cofounder for and owns equity in Optivia Biotechnology.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00539.

Experimental procedures and compound characterization for all new compounds (PDF)

Author Contributions

∥ Y.A. and O.N.B. contributed equally to the work.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Y.S. is a co-founder for and owns equity in Optivia Biotechnology.

Supplementary Material

References

- Heidelberger C.; Chaudhuri N. K.; Danneberg P.; Mooren D.; Griesbach L.; Duschinsky R.; Schnitzer R. J.; Pleven E.; Scheiner J. Fluorinated pyrimidines, a new class of tumour-inhibitory compounds. Nature 1957, 179, 663–666. 10.1038/179663a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longley D. B.; Harkin D. P.; Johnston P. G. 5-fluorouracil: mechanisms of action and clinical strategies. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2003, 3, 330–338. 10.1038/nrc1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald J. S. Toxicity of 5-fluorouracil. Oncology (Williston Park) 1999, 13, 33–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heggie G. D.; Sommadossi J. P.; Cross D. S.; Huster W. J.; Diasio R. B. Clinical pharmacokinetics of 5-fluorouracil and its metabolites in plasma, urine, and bile. Cancer Res. 1987, 47, 2203–2206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton J.; Lu X.; Hollenbaugh J. A.; Cho J. H.; Amblard F.; Schinazi R. F. Metabolism, biochemical actions, and chemical synthesis of anticancer nucleosides, nucleotides, and base analogs. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 14379–14455. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K.; Yoshisue K.; Matsushima E.; Nagayama S.; Kobayashi K.; Tyson C. A.; Chiba K.; Kawaguchi Y. Bioactivation of tegafur to 5-fluorouracil is catalyzed by cytochrome P-450 2A6 in human liver microsomes in vitro. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000, 6, 4409–4415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Sayed Y. M.; Sadée W. Metabolic activation of R,S-1-(tetrahydro-2-furanyl)-5-fluorouracil (ftorafur) to 5-fluorouracil by soluble enzymes. Cancer Res. 1983, 43, 4039–4044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoffski P. The modulated oral fluoropyrimidine prodrug S-1, and its use in gastrointestinal cancer and other solid tumors. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2004, 15, 85–106. 10.1097/00001813-200402000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono A.; Hara Y.; Sugata S.; Karube Y.; Matsushima Y.; Ishitsuka H. Activation of 5′-deoxy-5-fluorouridine by thymidine phosphorylase in human tumors. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1983, 31, 175–178. 10.1248/cpb.31.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishioka M.; Miyamoto H.; Kurita N.; Higashijima J.; Yoshikawa K.; Miyatani T.; Shimada M. Pyrimidine nucleoside phosphorylase and dihydropyrimidine dihydrogenase activities as predictive factors for the efficacy of doxifluridine together with mitomycin C as adjuvant chemotherapy in primary colorectal cancer. Hepatogastroenterology 2007, 54, 1089–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto J.; Oba K.; Matsui T.; Kobayashi M. Efficacy of oral anticancer agents for colorectal cancer. Dis. Colon Rectum 2006, 49, S82–91. 10.1007/s10350-006-0601-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimma N.; Umeda I.; Arasaki M.; Murasaki C.; Masubuchi K.; Kohchi Y.; Miwa M.; Ura M.; Sawada N.; Tahara H.; Kuruma I.; Horii I.; Ishitsuka H. The design and synthesis of a new tumor-selective fluoropyrimidine carbamate, capecitabine. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2000, 8, 1697–1706. 10.1016/S0968-0896(00)00087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hileman E. O.; Liu J.; Albitar M.; Keating M. J.; Huang P. Intrinsic oxidative stress in cancer cells: a biochemical basis for therapeutic selectivity. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2004, 53, 209–219. 10.1007/s00280-003-0726-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szatrowski T. P.; Nathan C. F. Production of large amounts of hydrogen peroxide by human tumor cells. Cancer Res. 1991, 51, 794–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyokuni S.; Okamoto K.; Yodoi J.; Hiai H. Persistent oxidative stress in cancer. FEBS Lett. 1995, 358, 1–3. 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01368-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushio-Fukai M.; Alexander R. W. Reactive oxygen species as mediators of angiogenesis signaling: role of NAD(P)H oxidase. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2004, 264, 85–97. 10.1023/B:MCBI.0000044378.09409.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa K.; Takenaga K.; Akimoto M.; Koshikawa N.; Yamaguchi A.; Imanishi H.; Nakada K.; Honma Y.; Hayashi J. ROS-generating mitochondrial DNA mutations can regulate tumor cell metastasis. Science 2008, 320, 661–664. 10.1126/science.1156906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dharmaraja A. T. Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in therapeutics and drug resistance in cancer and bacteria. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 3221–3240. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold R. S.; Shi J.; Murad E.; Whalen A. M.; Sun C. Q.; Polavarapu R.; Parthasarathy S.; Petros J. A.; Lambeth J. D. Hydrogen peroxide mediates the cell growth and transformation caused by the mitogenic oxidase Nox1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001, 98, 5550–5555. 10.1073/pnas.101505898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelicano H.; Feng L.; Zhou Y.; Carew J. S.; Hileman E. O.; Plunkett W.; Keating M. J.; Huang P. Inhibition of mitochondrial respiration: a novel strategy to enhance drug-induced apoptosis in human leukemia cells by a reactive oxygen species-mediated mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 37832–37839. 10.1074/jbc.M301546200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trachootham D.; Alexandre J.; Huang P. Targeting cancer cells by ROS-mediated mechanisms: a radical therapeutic approach?. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2009, 8, 579–591. 10.1038/nrd2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J.; Seki T.; Maeda H. Therapeutic strategies by modulating oxygen stress in cancer and inflammation. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2009, 61, 290–302. 10.1016/j.addr.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. M.; Wilson W. R. Exploiting tumour hypoxia in cancer treatment. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 437–447. 10.1038/nrc1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X.; Gandhi V. ROS-activated anticancer prodrugs: a new strategy for tumor-specific damage. Ther. Delivery 2012, 3, 823–833. 10.4155/tde.12.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y.; Xu L.; Ou S.; Edwards H.; Luedtke D.; Ge Y.; Qin Z. H2O2/Peroxynitrite-Activated Hydroxamic Acid HDAC Inhibitor Prodrugs Show Antileukemic Activities against AML Cells. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 635–640. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiro Cadahia J.; Bondebjerg J.; Hansen C. A.; Previtali V.; Hansen A. E.; Andresen T. L.; Clausen M. H. Synthesis and evaluation of hydrogen peroxide sensitive prodrugs of methotrexate and aminopterin for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 3503–3515. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E. J.; Bhuniya S.; Lee H.; Kim H. M.; Cheong C.; Maiti S.; Hong K. S.; Kim J. S. An activatable prodrug for the treatment of metastatic tumors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 13888–13894. 10.1021/ja5077684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.; Balakrishnan K.; Kuang Y.; Han Y.; Fu M.; Gandhi V.; Peng X. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) inducible DNA cross-linking agents and their effect on cancer cells and normal lymphocytes. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 4498–4510. 10.1021/jm401349g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang Y.; Balakrishnan K.; Gandhi V.; Peng X. Hydrogen peroxide inducible DNA cross-linking agents: targeted anticancer prodrugs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 19278–19281. 10.1021/ja2073824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dharmaraja A. T.; Ravikumar G.; Chakrapani H. Arylboronate ester based diazeniumdiolates (BORO/NO), a class of hydrogen peroxide inducible nitric oxide (NO) donors. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 2610–2613. 10.1021/ol5010643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar G.; Bagheri M.; Saini D. K.; Chakrapani H. A small molecule for theraNOstic targeting of cancer cells. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 13352–13355. 10.1039/C7CC08526E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzenell P.; Hagen H.; Sellner L.; Zenz T.; Grinyte R.; Pavlov V.; Daum S.; Mokhir A. Aminoferrocene-based prodrugs and their effects on human normal and cancer cells as well as bacterial cells. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 6935–6944. 10.1021/jm400754c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen H.; Marzenell P.; Jentzsch E.; Wenz F.; Veldwijk M. R.; Mokhir A. Aminoferrocene-based prodrugs activated by reactive oxygen species. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 924–934. 10.1021/jm2014937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daum S.; Chekhun V. F.; Todor I. N.; Lukianova N. Y.; Shvets Y. V.; Sellner L.; Putzker K.; Lewis J.; Zenz T.; de Graaf I. A.; Groothuis G. M.; Casini A.; Zozulia O.; Hampel F.; Mokhir A. Improved synthesis of N-benzylaminoferrocene-based prodrugs and evaluation of their toxicity and antileukemic activity. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 2015–2024. 10.1021/jm5019548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major Jourden J. L.; Cohen S. M. Hydrogen peroxide activated matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors: a prodrug approach. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 6795–6797. 10.1002/anie.201003819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degner A.; Carlsson H.; Karlsson I.; Eriksson J.; Pujari S. S.; Tretyakova N. Y.; Törnqvist M. Discovery of novel N-(4-Hydroxybenzyl)valine hemoglobin adducts in human blood. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2018, 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.8b00173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino S.; Itoh A.; Matsuoka H.; Maeda K.; Kamoshida S. Immunohistochemical analysis of organic anion transporter 2 and reduced folate carrier 1 in colorectal cancer: Significance as a predictor of response to oral uracil/ftorafur plus leucovorin chemotherapy. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 1, 661–667. 10.3892/mco.2013.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podhorecka M.; Skladanowski A.; Bozko P. H2AX Phosphorylation: its role in DNA damage response and cancer therapy. J. Nucleic Acids 2010, 2010, 920161. 10.4061/2010/920161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.; Fan H.; Balakrishnan K.; Wang Y.; Sun H.; Fan Y.; Gandhi V.; Arnold L. A.; Peng X. Discovery and optimization of novel hydrogen peroxide activated aromatic nitrogen mustard derivatives as highly potent anticancer agents. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 9132–9145. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser A.; Cory S.; Adams J. M. Deciphering the rules of programmed cell death to improve therapy of cancer and other diseases. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 3667–3683. 10.1038/emboj.2011.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malanga M.; Althaus F. R. The role of poly(ADP-ribose) in the DNA damage signaling network. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2005, 83, 354–364. 10.1139/o05-038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.