Abstract

Malaria is a major tropical disease where important needs are to mitigate symptoms and to prevent the establishment of infection. Cyclopeptides containing N-methyl amino acids with in vitro activity against erythrocytic forms as well as liver stage are presented. The synthesis, parasitological characterization, physicochemical properties, in vivo evaluation, and mice pharmacokinetics are described.

Keywords: Antiplasmodial, cyclopeptides, synthesis, physicochemical properties

Malaria is an infectious disease caused by Plasmodium spp. parasites and transmitted to human by the Anopheles vector mosquito. Among the six species that cause malaria in humans, P. falciparum is the most lethal. The World Health Organization 2017 report estimated 216 million malaria cases in 2016, principally in the sub-Saharan region.1 Efforts to control the disease, have decreased significantly the burden since 2000. However, this progression seems to be slowed and the estimated deaths in 2016 were 445,000, a number similar to the previous year, with the majority of infants under five years old.

The emergence of malaria parasite resistance to the available drugs including artemisinin and its derivatives,2−4 and the Anopheles vector resistance to the currently used insecticides, threaten malaria control efforts. Therefore, there is an urgent need of new and safe drugs capable to combat this illness. Recent investigations in antimalarial drug discovery have been centered on nonclassical chemical structures, new targets, and vaccines.5 A recent review by Burrows et al. enumerates the changes in antimalarial target candidate (TCP) and target product profiles (TPP) during the last years.6 In recent times, the development of new drugs has been directed to investigations of compounds that not only treat disease symptoms but also contribute toward the elimination and eradication of malaria. In order to accomplish eradication, new drugs should inhibit different parasite stages. However, most current antimalarials only mitigate the symptoms caused by the asexual erythrocytic stages of the parasite.7 Few types of these drugs, including atovaquone, a cytochrome bc1 inhibitor, and pyrimethamine, an antifolate drug, are active against liver as well as erythrocytic stage. Therefore, these compounds possess prophylactic activity as they are able to prevent the establishment of infection as well as to treat the disease symptoms.

In the last years, a significant number of macrocycles, with very interesting biological activities, have been described in the literature.8,9 This type of compounds are considering promising candidates in the discovery and development of new drugs, due to their properties. Briefly, they could adopt bioactive conformations and provide selectivity to the receptors as well as metabolic stability.10 In addition, it was demonstrated that multiple backbone N-methylation of cyclic peptides remarkably improves their cell permeability and therefore can be utilized in the design of new orally available drugs.11−13

Recently, our group has reported the synthesis of cyclopeptides and their evaluation as antiplasmodial candidates.14,15 Based on the potential for macrocycles as drugs and on our previous work, we decided to prepare analogs of cyclopeptides, containing N-methyl amino acids (N-Me-AA) to evaluate how N-methylation affects the bioactivity of these antimalarial compounds. In this work we disclose, the synthesis of nine cyclopeptides, their physicochemical properties, and their intraerythrocytic antiplasmodial activity and selectivity. In addition, two compounds were evaluated against the liver stage of the parasite and two cyclopeptides were selected to assess the in vivo activity in mice infected with P. berghei. Moreover, animal pharmacokinetics for one of these compounds was determined.

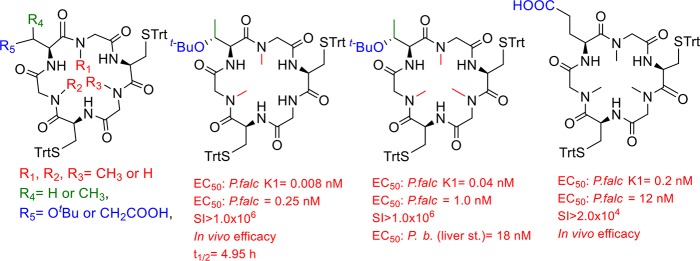

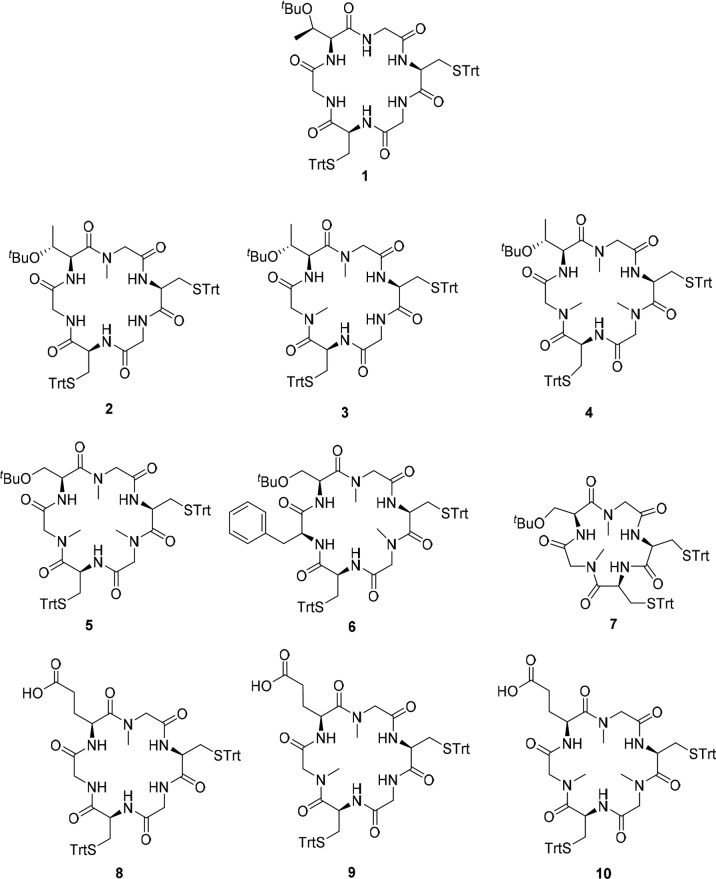

Previously, our research team reported the synthesis and antiplasmodial activity of compound 1 (EC50 = 28 nM, Figure 1).15 In this study, we concluded that the presence of three Gly, one Thr, and two Cys in the cyclohexapeptide had a great impact on the biological activities. Based on this structure, we prepared three analogs, 2, 3, and 4 containing one, two, or three N-Me-Gly, respectively, to investigate how these changes affect the inhibitory activity of this series. In addition, Thr(OtBu) in 4 was replaced by Ser(OtBu) to obtain 5. Cyclohexapeptide 6 and cyclopentapeptide 7 were obtained by substitution of N-Me-Gly with Phe or elimination of one N-Me-Gly in 5, respectively. That substitution was based in our previous results,14 where the presence of Phe in cyclopeptide sequence improved the antiplasmodial activity. Compounds 8–10 are close analogs of 2–4, respectively, which were obtained by replacements of Thr(OtBu) with Glu in order to increase solubility at pH = 7.4.

Figure 1.

Cyclopeptides analogs synthesized in this work (2–10) and lead compound 1.15

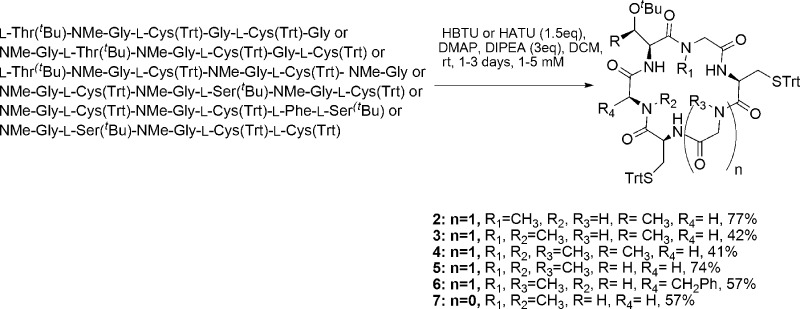

Compounds 2–7 were synthesized employing SPPS and solution macrocyclization (Scheme 1). The 2-chlorotrityl resin (2-CTC) was used to decrease the diketopiperazine formation,16 and HBTU and DIPEA were employed as coupling reagents in most cases. HCTU and DIPEA resulted in a more effective reagent for the coupling of the next amino acid to N-Me-Gly. DIC and Cl-HOBt were employed to activate the Fmoc-l-Cys(Trt)-OH and perform the coupling to the peptide attached to the resin, in order to minimize racemization of Cys residue.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Cyclopeptides by Solution Macrocyclization.

To reduce the possibility of racemization and also the steric hindrance during ring closure reaction,17 the peptide precursor of 2 was started with glycine at the C-terminus. The first attempts to prepare peptide precursors of 3, 6, and 7 using N-Me-Gly as the first or second amino acid attached to the resin resulted in low yields probably due to the formation of diketopiperazine favored by the turn-inducing N-Me amino acid. For this reason, to obtain these precursors in high yield, we selected sequences where N-Me-Gly was not the first or second amino acid. However, the peptide precursors of 4 and 5 were obtained in very good yields, using N-Me-Gly as first or second amino acid attached, respectively. In addition, the macrocyclizations proceeded in good yields, and no racemization was observed by the HPLC analyses and the NMR spectra.

Concerning the macrocyclization reaction, the longest reaction time is for the synthesis of 2, which contains only one turn-inducing N-Me-Gly. Cyclopeptides 2 and 5 were obtained in very good yields (77 and 74%) and the rest of the cyclopeptides (3, 4, 6, and 7) in good yields (41–57%).

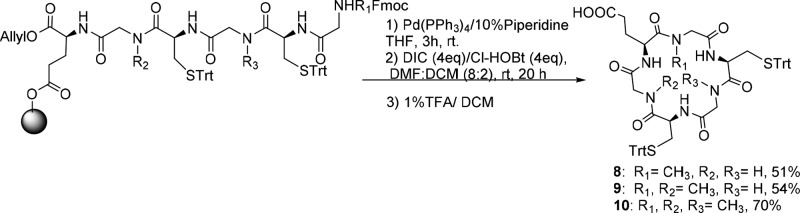

Compounds 8, 9, and 10 were synthesized employing on-resin macrocyclization, Scheme 2.15 First, Fmoc-l-Glu-OAll was anchored to 2-CTC resin with DIPEA, and then, Fmoc SPPS protocol was followed. After the removal of the allyl ester and Fmoc group with [Pd(PPh3)4] in a solution of 10% piperidine in THF, the ring closure was performed using DIC and Cl-HOBt. The HPLC chromatograms and the NMR spectra of the crude cyclopeptide did not show the presence of undesired diastereomers, which would be obtained if macrocyclization occurred with racemization. Therefore, the overall yields for the synthesis of cyclopeptides, based on the determination of the resin loading, were between 51 to 70%.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Cyclopeptides by On-Resin Cyclization.

The obtained compounds were evaluated in vitro against chloroquine resistant P. falciparum K1 (24 h incubation, 3H-hypoxanthine incorporation readout),18 and drug sensitive P. falciparum 3D7 (SYBR Green assay),19Table 1. The results for compounds 2 and 3, which present the same sequence as that of compound 1, allowed us to conclude that the activity against both parasite strains is improved with the growing number of N-Me-Gly. However, cyclopeptide 4, which presents three N-Me-Gly is less active than 3. The substitution of Thr(tBu) in 4 by Ser(tBu) in 5 diminishes the activity against both strains. Moreover, the EC50 is higher for cyclopentapeptide 7 where one N-Me-Gly in 5 was eliminated. Cyclohexapeptide 6 which presents a Phe instead of N-Me-Gly in 5 is less active against the two strains. Compounds 8 and 9, analogs to 2 and 3 (Glu by Thr(tBu)), are inactive against P. falciparum 3D7. However, cyclopeptide 10, analog to 4, showed subnanomolar EC50 against K1 and 12 nM against 3D7 strain. It seems that when a Glu, with the free carboxyl group, is present, three N-Me-Gly would be required to maintain the activity. Moreover, all active compounds are not toxic against murine macrophage or HepG2 cells, showing excellent selectivity (SI).

Table 1. Parasite Growth Inhibition Expressed as EC50 (nM) and Selectivity Indexa.

| cyclopeptide | EC50/EC90P. falciparum K1 (nM)b | EC50P. falciparum 3D7 (nM)c | SI IC50d/EC50PfK1 | SI IC50e/EC50Pf3D7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 8.0 ± 0.5/39 ± 3 | 3.8 ± 0.1 | >12500 | >6.6 × 104 |

| 3 | 0.008 ± 0.004/1.0 ± 0.5 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | >1.3 × 107 | >1.0 × 106 |

| 4 | 0.040 ± 0.006/1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | >2.5 × 106 | >2.5 × 105 |

| 5 | 0.13 ± 0.04/4.0 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | >7.7 × 105 | >1.8 × 105 |

| 6 | 9.0 ± 0.5/59 ± 3 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | >1.1 × 104 | >1.4 × 105 |

| 7 | 150 ± 5/900 ± 9 | nt | nt | nt |

| 8 | nt | 5400 ± 100 | nt | >46 |

| 9 | nt | 210 ± 10 | nt | >1.2 × 103 |

| 10 | 0.20 ± 0.04/4.0 ± 0.6 | 12 ± 1 | 5 × 105 | >2 × 104 |

Values represent the mean ± SD (n = 2).

Control: chloroquine, EC50 = 0.47 μM; Artemisinin, EC50 = 20 nM; Artesunate, EC50 = 3 nM.

Control: Pyrimethamine, EC50 = 35 nM; Artesunate, EC50 = 5 nM.

Cytotoxicity against murine macrophages J774.

Cytotoxicity against HepG2 cells; nt: not tested.

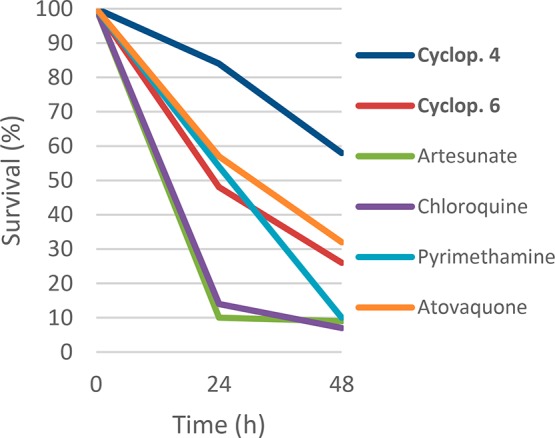

Then, compounds 4 and 6 were assessed in an in vitro assay where the capability of drug treated parasite to undergo new invasions is used as surrogate of parasite viability.20 A double-colorimetric FACTS analysis is used to quantify new invasions of prestained hRBCs by drug treated parasites. This assay uses a two-time-point drug treatment to distinguish rapidly parasiticidal compounds from moderate or slow acting antimalarials. Figure 2 shows the in vitro results for 4, 6, and four standard antimalarial drugs (chloroquine, atovaquone, pyrimethamine, and artesunate), which were included to validate the results produced and allow a comparative classification of the killing behavior of the compounds tested. Both compounds displayed estimated effects over parasite viability comparable to slow agents: atovaquone and pyrimethamine, which finally impair pyrimidine biosynthesis. These results point to an antimalarial mode of action that does not produce a rapid effect on parasite viability.

Figure 2.

Killing profile against P. falciparum 3D7A strain for compound 4, 6, artesunate, chloroquine, atovaquone, and pyrimethamine tested at 10 times the EC50 (number of replicates n = 2).

To assess the prophylactic potential of this series, we used the luciferase-based phenotypic screen of malaria exoerythrocytic stage. This assay uses the exoerythrocytic stage of the rodent malaria parasite, Plasmodium berghei, and a human hepatoma cell line.21 As cyclopeptides 4 and 6 differ in the amino acid sequence and in the number of N-Me, they were selected to evaluate their effect in the liver stage of the parasite, showing low and submicromolar EC50 values (0.018 and 0.335 μM, respectively; control: atovaquone, EC50 = 2.8 nM).

Next, determination of physicochemical properties, Log D, solubility, and permeability was performed, Table 2. Taking into account the three properties of the most active compounds (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 10), compounds 2, 3, and 10 could be selected as the more promising to intend the in vivo evaluation, as they are the most soluble or present higher Pe. However, as 3 and 10 had lower EC50 values against the two P. falciparum strains than 2 (Table 1), they were chosen as representative compounds to assess the in vivo activity.

Table 2. Physicochemical Properties Determined for the Cyclopeptides.

| cyclopeptide | Log D, pH 7.0a | solubility PBS, pH 7.4/pH 1.0 (μM)b | PAMPA (Pe × 10–6 cm/s)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 5.8 | 0.94/1.17 | 0.6 |

| 3 | 6.0 | 0.38/3.46 | 1.0 |

| 4 | 3.7 | 0.55/0.38 | 0.2 |

| 5 | 6.3 | 0.18/0.74 | 0.3 |

| 6 | 8.0 | 0.71/5.32 | 0.2 |

| 7 | 7.7 | 0.12/0.21 | 2.0 |

| 8 | 3.1 | nd | d |

| 9 | 3.7 | nd | e |

| 10 | 3.9 | 436.52/28.33 | 0.2 |

Measured (see Supporting Information).

Number of replicates, n = 2.

Number of replicates, n = 3; nd: not determined.

Compound was not detected in the acceptor compartment (lower limit of quantitation, LLOQ = 0.02 μM).

Compound was not detected in the acceptor compartment (lower limit of quantitation, LLOQ = 0.03 μM).

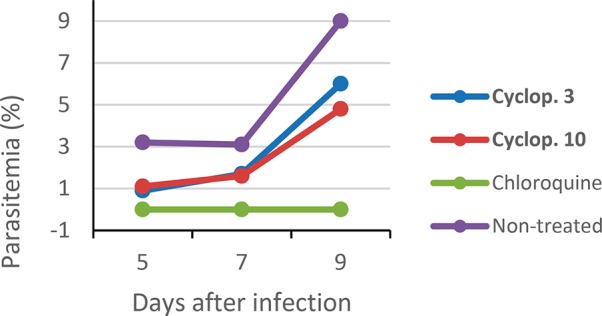

A suppressive growth test was used with P. berghei NK65 strain infected mice as described previously.22 Briefly, Swiss outbred mice were inoculated with infected red blood cells. On days 2, 3, and 4, administration of a single oral dose of each compound (50 mg·kg–1) was carried out. Two control groups were used, one treated with chloroquine and the other with vehicle. Blood smears from the mouse tails were prepared on days 5, 7, and 9 postinfection, then the parasitemia was evaluated and the percent inhibition of parasite growth calculated (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

In vivo evaluation of cyclopeptides 3 and 10 (number of replicates n = 3).

Cyclopeptides 3 and 10 were actives against P. berghei parasites reducing 71 and 66% of the parasitemia on day 5, respectively. Even though it was not possible to obtain a 100% reduction during this study, the parasitemia was reduced until day 9. In order to evaluate the oral bioavailability, plasma pharmacokinetic of compound 3 in male Swiss Albino mice following a single oral administration was investigated.23 Animals were administered with solution formulation of 3 via oral route at 50 mg/kg. The blood samples were collected at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h. Plasma concentrations of 3 were quantifiable up to 12 h (lower limit of quantitation 5.16 ng/mL). The determinate pharmacokinetic parameters are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Cyclopeptide 3 (Number of Replicates, n = 3).

| Tmax (h) | Cmax (ng/mL) | AUClast (h·ng/mL) | AUCinf (h·ng/mL) | T1/2 (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.00 | 61.1 | 314.8 | 390.7 | 4.93 |

The results demonstrate that compound 3 reaches maximum concentration at 2 h, with T1/2 = 4.93 h. It is worth noting that the mean plasma concentrations between 0.5 to 12 h were higher than 9 ng/mL (see Supporting Information).

In conclusion, a new class of antimalarial cyclopeptides containing N-methyl Gly with enhanced antiplasmodial activity has been reported. The compounds were rapidly accessed using SPPS and solution or on-resin macrocyclization. The parasitological profiling demonstrated improved activity of cyclopeptides containing N-Me-Gly, compared with 1, with EC50 in a low nanomolar or subnanomolar range against P. falciparum K1 and 3D7. Cyclopeptides 4 and 6 showed parasite viability comparable to atovaquone and pyrimethamine, which impair pyrimidine biosynthesis. In addition, these compounds are active against the liver stage of the parasite showing submicromolar EC50. Cyclopeptides 3 and 10 have confirmed in vivo efficacy, and 3 presents a considerable half-life of 4.93 h. Investigations toward elucidating the mechanism of action underlying this series are in progress and will be reported in the due course.

Acknowledgments

Assistance from Medicines for Malaria Venture and Paul Willis is gratefully acknowledged. This work was supported by Grants from CSIC Grupos 983 (Universidad de la República), British Embassy in Uruguay, PEDECIBA (Uruguay), FAPESP (CEPID Grant 2013/07600-3), CNPq (Grant 405330/2016-2), and Serrapilheira Institute (Grant Serra-1708-16250). The authors acknowledge Ph.D. fellowships from ANII (Agencia Nacional de Investigación e Innovación) (Catherine Fagundez, Stella Peña) and an internship supported by PEDECIBA.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- SPPS

solid phase peptide synthesis

- SI

selectivity index

- RBCs

red blood cells

- PAMPA

parallel artificial membrane permeability assay

- Pe

experimental permeability

- AUC

area under plasma concentration–time curve

- Cmax

maximum concentration

- Tmax

time to reach maximum concentration

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00543.

Synthesis and analytical data of the obtained cyclopeptides, details for P. falciparum in vitro and in vivo assays, physicochemical and mouse pharmacokinetic studies (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

All animal experiments were performed according to national animal welfare regulations after authorization by the local authorities (Universidade Federal de São Paulo, CEUA N 6630080816).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- WHO . World Malaria Report 2017; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Dondorp A. M.; Nosten F.; Yi P.; Das D.; Phyo A. P.; Tarning J.; Lwin K. M.; Ariey F.; Hanpithakpong W.; Lee S. J.; Ringwald P.; Silamut K.; Imwong M.; Chotivanich K.; Lim P.; Herdman T.; An S. S.; Yeung S.; Singhasivanon P.; Day N. P.; Lindegardh N.; Socheat D.; White N. J. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 455. 10.1056/NEJMoa0808859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leang R.; Taylor W. R.; Bouth D. M.; Song L.; Tarning J.; Char M. C.; Kim S.; Witkowski B.; Duru V.; Domergue A.; Khim N.; Ringwald P.; Menard D. Evidence of Plasmodium falciparum Malaria Multidrug Resistance to Artemisinin and Piperaquine in Western Cambodia: Dihydroartemisinin-Piperaquine Open-Label Multicenter Clinical Assessment. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 4719. 10.1128/AAC.00835-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noedl H.; Se Y.; Schaecher K.; Smith B. L.; Socheat D.; Fukuda M. Evidence of artemisinin-resistant malaria in western Cambodia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 2619. 10.1056/NEJMc0805011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okombo J.; Chibale K. Recent updates in the discovery and development of novel antimalarial candidates. MedChemComm 2018, 9, 437. 10.1039/C7MD00637C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrows J.; Duparc S.; Gutteridge W. E.; Hooft van Huijsduijnen R.; Kaszubska W.; Macintyre F.; Mazzuri S.; Möhrle J. J.; Wells T. N. C. New developments in anti-malarial target candidate and product profiles. Malar. J. 2017, 16, 26. 10.1186/s12936-016-1675-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delves M.; Plouffe D.; Scheurer C.; Meister S.; Wittlin S.; Winzeler E. A.; Sinden R. E.; Leroy D. The activities of current antimalarial drugs on the life cycle stages of Plasmodium: a comparative study with human and rodent parasites. PLoS Medicine 2012, 9, e1001169 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordanetto F.; Kihlberg J. Macrocyclic Drugs and Clinical Candidates: What Can Medicinal Chemists Learn from their Properties?. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 278. 10.1021/jm400887j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña S.; Scarone L.; Serra G. Macrocycles as potential therapeutic agents in neglected diseases. Future Med. Chem. 2015, 7, 355. 10.4155/fmc.14.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallinson J.; Collins I. Macrocycles in new drug discovery. Future Med. Chem. 2012, 4, 1409. 10.4155/fmc.12.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt W. M.; Leung S. S. F.; Pye C. R.; Ponkey A. R.; Bednarek M.; Jacobson M. P.; Lokey R. S. Cell-Permeable Cyclic Peptides from Synthetic Libraries Inspired by Natural Products. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 715. 10.1021/ja508766b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doedens L.; Opperer F.; Cai M.; Beck J. G.; Dedek M.; Palmer E.; Hruby V. J.; Kessler H. Multiple N-methylation of MT-II backbone amide bonds leads to melanocortin receptor subtype hMC1R selectivity: pharmacological and conformational studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 8115. 10.1021/ja101428m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovadia O.; Greenberg S.; Chatterjee J.; Laufer B.; Opperer F.; Kessler H.; Gilon C.; Hoffman A. The effect of multiple N-methylation on intestinal permeability of cyclic hexapeptides. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2011, 8, 479. 10.1021/mp1003306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña S.; Fagundez C.; Medeiros A.; Comini M.; Scarone L.; Sellanes D.; Manta E.; Tulla-Puche J.; Albericio F.; Stewart L.; Yardley V.; Serra G. Synthesis of Cyclohexapeptides as Antimalarial and Anti-trypanosomal Agents. MedChemComm 2014, 5, 1309. 10.1039/C4MD00135D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fagundez C.; Sellanes D.; Serra G. Synthesis of Cyclic Peptides as Potential Anti-Malarials. ACS Comb. Sci. 2018, 20, 212. 10.1021/acscombsci.7b00154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlos K.; Gatos D.; Schäfer W. Synthesis of prothymosin a (ProTo)—a protein consisting of 109 amino acid residues. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1991, 30, 590. 10.1002/anie.199105901. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey J.; Chamberlin A. Chemical synthesis of natural product peptides: coupling methods for the incorporation of noncoded amino acids into peptides. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 2243. 10.1021/cr950005s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins R. E.; Canfield C. J.; Haynes D. E.; Chulay J. D. Quantitative assessment of antimalarial activity in vitro by a semiautomated microdilution technique. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1979, 16, 710. 10.1128/AAC.16.6.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smilkstein M.; Sriwilaijaroen N.; Kelly J. X.; Wilairat P.; Riscoe M. Simple and inexpensive fluorescence-based technique for high-throughput antimalarial drug screening. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 1803. 10.1128/AAC.48.5.1803-1806.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linares M.; Viera S.; Crespo B.; Franco V.; Gómez-Lorenzo M. G.; Jiménez-Díaz M. B.; Angulo-Barturen I.; Sanz L. M.; Gamo F. J. Identifying rapidly parasiticidal anti-malarial drugs using a simple and reliable in vitro parasite viability fast assay. Malar. J. 2015, 14, 441. 10.1186/s12936-015-0962-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann J.; Corey V.; Scherer C. A.; Kato N.; Comer E.; Maetani M.; Antonova-Koch Y.; Reimer C.; Gagaring K.; Ibanez M.; Plouffe D.; Zeeman A.-M.; Clemens H.; Kocken C. H. M.; McNamara C. W.; Schreiber S. L.; Campo B.; Winzeler E. A.; Meister S. ACS Infect. Dis. 2016, 2, 281–293. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.5b00143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters W. Drug resistance in Plasmodium berghei Vinckle and Lips, 1948. I. Chloroquine resistance. Exp. Parasitol. 1965, 17, 80–89. 10.1016/0014-4894(65)90012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- This study was performed at Sai Life Sciences Limited, India.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.