Abstract

Concurrent delivery of multiple drugs using nanoformulations can improve outcomes of cancer treatments. Here we demonstrate that this approach can be used to improve the paclitaxel (PTX) and alkylated cisplatin prodrug combination therapy of ovarian and breast cancer. The drugs are co-loaded in the polymeric micelle system based on amphiphilic block copolymer poly(2-methyl-2-oxazoline-block-2-butyl-2-oxazoline-block-2-methyl-2-oxazoline) (P(MeOx-b-BuOxb-MeOx). A broad range of drug mixing ratios and exceptionally high two-drug loading of over 50 wt.% drug in a stable micellar solution is demonstrated. The drugs co-loading in the micelles result in a slowed-down release to serum, improved pharmacokinetics and increased tumor distribution for both drugs. A superior anti-tumor activity of co-loaded PTX/CP drug micelles compared to single drug micelles or their mixture was demonstrated in cisplatin-resistant human ovarian carcinoma A2780/CisR xenograft tumor and multidrug resistant breast cancer LCC-6-MDR orthotopic tumor models. The improved tumor delivery of co-loaded drugs was related to decreased drug release rates as confirmed by simulation for micelle, serum and tumor compartments in a three-compartmental model. Overall, the results provide support for the use of PTX and cisplatin co-loaded micelles as a strategy for improved chemotherapy of ovarian and breast cancer and potential for the clinical translation.

Keywords: cancer, combination chemotherapy, poly (2-oxazoline), polymeric micelle, nanoformulation

Introduction

The combination chemotherapy using sequential administration of paclitaxel (PTX) followed by a platinum-based regimen is currently the first-line therapy for ovarian cancer as well as common treatment for breast cancer [1, 2]. PTX is a member of taxanes family, which arrest cells in the G2/M phase by binding to the β-tubulin subunits, inhibiting depolymerization of microtubules and cause apoptosis through cell-signaling cascades [3]. However, taxanes, including PTX, are very poorly soluble and thereby require the use of toxic excipients in clinical formulations, such as Cremophor EL in Taxol, which can cause severe hypersensitivity reactions in patients. Platinum anticancer drugs, such as cisplatin, the most potent member of the platinum drug family, penetrate into the nucleus of cancer cells and form adducts with DNA leading to apoptosis [4]. Clinical use of cisplatin is complicated by the dose-limiting side effects as well as rapid development of drug resistance [5]. Moreover, cisplatin also has formulation issues such as relatively low solubility in both aqueous and organic solvents [6].

Co-delivery of drug combinations in the same vehicle may improve the chemotherapy of tumors by synchronizing their exposure to the drugs and achieving synergistic pharmacological action in the tumor cells [7]. Hence, the delivery of multiple chemotherapeutic agents in a single nanoparticle carrier has attracted attention as a strategy for improving treatment responses, reducing side effects, and overcoming drug resistance [8]. One major success of this strategy is exemplified by a recent approval by the US Food and Drug Administration of Vyxeos (CPX-351), a liposomal combination of daunorubicin and cytarabine, for newly diagnosed therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia (t-AML) in adult patients and AML with myelodysplasia-related changes (AML-MRC) [7]. Moreover, several preclinical formulations of multiple drugs co-loaded into various nanoparticle carriers have also been evaluated and shown some promise for the treatment of cancers [9, 10].

A principal bottleneck in the development of co-loaded drug nanoformulations is that many drugs have poor miscibility with each other and many nanoparticle carriers have a fairly low loading threshold for such drugs. One novel drug carrier system that stands apart from the others in that regard is polymeric micelles [11], based on amphiphilic block copolymers of poly(2-alkyl-2-oxazoline)s and specifically the poly[(2-methyl-2-oxazoline)-b-(2-butyl-2-oxazoline)-b-(2-methyl-2-oxazoline)] (P(MeOx-BuOx-MeOx) triblock copolymer [12]. Interestingly, despite the mild hydrophobicity of the core-forming PBuOx block, we have found that triblock copolymer P(MeOx-BuOx-MeOx) exhibits an unprecedentedly high capacity for solubilization of extremely hydrophobic drugs, including taxanes, and several drug combinations [13, 14]. For many drugs, the aqueous POx micelle solutions can be readily prepared that contain 10 to 50 g/L of extremely poorly soluble drug and are stable for days and weeks. The solubility of these drugs in POx micelles system is increased by a factor of 1,000 to 100,000 times. The amount of POx micelles excipient needed to prepare such solutions is dozens to hundreds of times less than the amounts of excipients used in current formulations of water-insoluble drugs. Specifically, PTX POx micelles have ca. 4 to 100 times higher drug loading and ca. 10 to 20 times higher drug concentration than the current PTX clinical formulations Taxol, Genexol-PM, and Abraxane. This alone have been shown to be highly beneficial for cancer treatment in animal tumor models by decreasing the excipient-related toxicity, widening the therapeutic index and allowing high dose PTX therapy [15]. Here demonstrate possibilities of the POx micelle platform for the co-delivery of PTX and hydrophobic cisplatin prodrugs (CP) to significantly improve the treatment of ovarian and breast cancer in animal tumor models and discuss possible rationale for the improved drug delivery and anti-cancer activity of co-loaded drugs compared to single drug loaded micelles and their combination.

Materials and methods

Materials

Amphiphilic triblock copolymers P(MeOx37-b-BuOx21-b-MeOx36), Mn=10.0 kg/mol, Đ (Mw/Mn) = 1.14 were synthesized as previously described [15]. PTX was purchased from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA). Hydrophobic derivatives of cisplatin, with aliphatic chains of different length (n = 4, 6, 8 and 10 carbon atoms) at the axial positions, C6CP, C8CP, and C10CP, were synthesized as previously described [16]. (see Supplementary materials and Supplementary Figures S1–S3 for the details of the synthesis and characterization). All other materials were from Fisher Scientific Inc. (Fairlawn, NJ), all reagents were HPLC grade and used as received. The A2780 cells and A2780/CisR (cisplatin resistant) cells were originally obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. MDA435/LCC-6-mdr1 (LCC-6-MDR) cells were originally obtained from Dr. R. Clarke, Georgetown University Medical School, Washington, DC. LCC-6-MDR cells, which express high levels of P-glycoprotein (P-gp), were derived from LCC-6-WT (wildtype) cells stably transfected with a retrovirus engineered to constitutively express the mdr1 gene [11]. The parent LCC-6-WT cells were derived from estrogen receptor (ER)-negative, aggressive and metastatic MDA-MB-435 cells. A2780 and A2780/CisR cells were cultured in RPMI1640 medium (Gibco 11875–093), and LCC-6-MDR cells were cultured in DMEM medium (Gibco 11965–092) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Nude mice were purchased from UNC DLAM animal facility.

Methods

Preparation and characterization of POx-based polymeric micelles

PTX/CP PM were prepared by a thin film method as previously described [15]. Briefly, pre-determined volumes of POx, PTX and CP stock solutions (5 g/L in ethanol) were mixed, followed by complete evaporation of ethanol. Appropriate amounts of normal saline were used to rehydrate the dried thin-film (under heating at 50–60°C for PTX PM and CP/PTX PM and room temperature for CP PM) for up to 15 min in order to obtain drug loaded PM. The excess of non-incorporated drug was removed by centrifugation. The resulting micelle formulation was stored as aqueous solution in refrigerator for up to 2 weeks or as lyophilized powder for long-term storage. We did not observe effects of long term-storage on the particle size or drug loading.

The drug concentrations in PM were determined by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method using an Eclipse XDB-C18–5μm column (150 mm × 4.6 mm) and Agilent 1200 HPLC. Each sample was diluted 20 times in mobile phase (acetonitrile/water; 50/50, v/v) and 20 L of the diluted sample was injected into the HPLC. The drugs were detected by a gradient method consisting of solvent A (water) and B (acetonitrile), where the gradient started at 50% B and kept for 3 min; changed to 20% B in 4 min and kept for 3 min; and changed back to 50% B in 2 min and kept for 3 min. The retention times of C4CP, C6CP, C8CP, C10CP and PTX were approximately 2.9 min, 6.9 min, 9.7 min, 12.6 min, and 4.7 min, and the detection wavelength was 245 nm and 227 nm (PTX) while the flow rate was 1.0 mL/min and column temperature was 30°C. A standard curve range from 5 μg/mL to 1000 μg/mL was used to calibrate the quantity of each drug.

The drug loading capacity, and loading efficiency (LE) were calculated using following equations (1)–(2): where Mdrug and Mexcipient are the weight amounts of the loaded (solubilized) drug and polymer excipient in the dispersion, while Mdrug added is the weight amount of the drug initially added to the dispersion.

| (1) |

| (2) |

A Nano-ZS (Malvern Instruments Inc., UK) dynamic light scattering (DLS) equipment was used to measure size distribution of POx micelles. Briefly, each sample was diluted 10 times with DI H2O to yield 1 g/L final polymer concentration before the measurement. The intensity-mean z-averaged particle size (effective diameter) and the polydispersity index (PDI) of PM were determined by cumulate analysis. Results are the average of three independent micelle samples measurements. The morphology of PM was studied using a LEO EM910 TEM operating at 80 kV (Carl Zeiss SMT Inc., Peabody, MA). Digital images were obtained using a Gatan Orius SC1000 CCD Digital Camera in combination with Digital Micrograph 3.11.0 software (Gatan Inc., Pleasanton, CA). One drop of each PM solutions (diluted 200 times using DI H2O) was deposited on a copper grid/carbon film for 5 min and excess solution was wicked off using fine filter paper. Then one drop of staining solution (1% uranyl acetate) was added and allowed to dry for 10 s prior to the TEM imaging.

In vitro drug release studies

The drug release PTX/CP PM was studied by membrane dialysis under the “perfect sink conditions”. Briefly, drug loaded PM were diluted to 0.1 g/L total drug in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4 containing 40 g/L bovine serum albumin (BSA). The micelle solutions (100 μL) were placed in floatable Slide-A-Lyzer MINI dialysis devices (100 μL, 20 kDa MWCO; Thermo Scientific) and dialyzed against 20 mL PBS containing 40 g/L BSA. Three devices were used for every time point. At each time point the samples were withdrawn from dialysis device and remaining drug amounts were determined quantified by HPLC and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). Drug release profiles were constructed by plotting the amount of drug(s) released over time.

In vitro cytotoxicity assays

In vitro cytotoxicity of free and micelle incorporated drugs was determined using [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] (MTT) assay in A2780 and A2780/CisR ovarian cancer cell lines as well as LCC-6-MDR breast cancer cell line. Briefly, cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 3000 cells/well 24 h prior to drug treatment and then treated with drugs serially diluted in full medium. After 72 h the medium was removed and MTT (100 g/well) in 100 L of fresh medium was added for additional 4h at 37°C. Then the medium was discarded, the formed formazan salt dissolved in 100 L of dimethyl sulfoxide and absorbance at 562 nm recorded using a plate reader (SpectraMax M5, Molecular Devices). Cell survival rates were calculated in comparison to control untreated wells. Data represent average of six wells in means ± standard deviation [17]. The mean drug concentration required for 50% growth inhibition (IC50) was determined using Graphpad Prism 5 software. The combination Index [18] analysis based on the Chou and Talalay method [19] was done using CompuSyn software. Briefly, for each level of factor Fa the CI of binary drug combinations were calculated using: CI=(D)1/(Dx)1+(D)2/(Dx)2, where (Dx)1 and (Dx)2 are the concentrations of each drug alone resulting in Fa × 100% growth inhibition, while (D)1 and (D)2 are the concentrations of each drug in the combination leading to Fa × 100 % growth inhibition. CI values of the drug combinations were plotted as a function of Fa. Generally, the CI values between Fa = 0.2 and Fa = 0.8 are considered valid. The best-fit CI value at IC50 is used to show and compare the synergistic effects of drug combinations with different drug ratios or for different cell lines. CI values below 1 or above 1 suggest drug synergy and antagonism respectively. CI values below 0.3 are considered strong synergy [13, 17].

Pharmacokinetics [20] and tumor accumulation

Female athymic nude mice (6–8 weeks) with well-developed 100 mm3 A2780/CisR xenograft tumors were administered intravenously [17] via tail vein with a single dose of the following formulations: 1) C6CP/PTX PM (20 mg/kg C6CP and 20 mg/kg PTX mouse body weight), 2) C8CP/PTX PM (20 mg/kg C8CP and 20 mg/kg PTX mouse body weight), 3) C6CP PM (20 mg/kg C6CP), 4) C8CP PM (20 mg/kg C8CP), and 5) PTX PM (20 mg/kg PTX). All injections contained 64Cu-labelled POx (4 μCi/mouse) and PTX injections contained 3H-PTX (5 μCi/mouse). 64Cu-labelled POx was synthesized as described in Supplementary methods. At various time points 0.083, 0.5, 1, 2, 6, and 15 h post injection three animals from every treatment group were euthanized, the blood was collected by cardiac puncture, the organs (spleen, liver, kidney) and the tumor was removed, washed in ice-cold saline, weighted and homogenized in a glass tissue homogenizer (Tearor™, BioSpec Products, Inc.). Polymer and drug concentrations in plasma, organs and tumors were measured by radioactivity counts using a γ-counter (PerkinElmer) for 64Cu-labelled POx, and liquid scintillation counter, Tricarb 4000 for 3H-PTX or by determining platinum content by ICP-MS for C6CP or C8CP. PK parameters were determined with Phoenix WinNonlin (version 6.0) software using non-compartmental analysis.

Efficacy and tumor accumulation studies

The maximal tolerated dose (MTD) was estimated prior to the in vivo efficacy studies. Healthy 6–8 weeks old female nude mice, which received escalating doses of the combination drugs: 1) 10/10, 20/20 or 30/30 mg/kg of PTX/C6CP PM (2/2/10) or PTX/C8CP PM (2/2/10), or 2) 40/3, 60/4.5 and 80/6 mg/kg of PTX/C6CP PM (40/3/50), using a q4d x 4 regimen (total 4 times repeated dosing). Mice well-being and body weight changes were monitored daily over two weeks in all groups. The highest dose that did not cause animal death or noticeable toxicity (as defined by a median body weight loss of 15% of the control or abnormal behavior including hunched posture and rough coat) was used as MTD for efficacy experiments.

A2780/CisR ovarian cancer xenograft model

Female athymic nude mice (6-week-old) were subcutaneously (s.c.) inoculated in the right flank with 8 × 106 human A2780/CisR ovarian cancer cell resuspended in 50% growth medium and 50% Matrigel. Animals were randomized into groups of five or six mice, each group having approximately same mean tumor volumes of ~ 300 mm3, and then administered via tail vein using q4d x 4 regimen (days 0. 4. 8. 12) with the test articles. In one study the injection solutions were: 1) PTX/C6CP PM (2/2/10) (20 mg/kg PTX and 20 mg/kg C6CP); 2) PTX/C8CP PM (2/2/10) (20 mg/kg PTX and 20 mg/kg C8CP); 3) PTX PM (2/10) and C6CP PM (2/10) mixture (20 mg/kg PTX and 20 mg/kg C6CP); 4) PTX PM (2/10) and C8CP PM (2/10) mixture (20 mg/kg PTX and 20 mg/kg C8CP); 5) PTX PM (2/10) (20 mg/kg PTX); 6) C6CP PM (2/10) (20 mg/kg C6CP); 7) C8CP (2/10) PM (20 mg/kg C8CP); 8) cisplatin (3 mg/kg), and 9) saline. In another study the injected solutions were: 1) PTX/C6CP PM (40/3/50) (60 mg/kg PTX and 4.5 mg/kg C6CP); 2) PTX PM (40/50) and C6CP PM (3/50) mixture (60 mg/kg PTX and 4.5mg/kg C6CP); 3) PTX PM (40/50) (60 mg/kg PTX); 4) C6CP PM (3/50) (4.5 mg/kg C6CP); 5) 3 mg/kg cisplatin and 6) saline. Tumor volume and survival were monitored twice weekly and end-points defined by tumor volume (> 2000 mm3), animal weight loss (> 15%), or animals becoming moribund. Tumor length (L), width (W) were measured and tumor volume (TV) was calculated as TV =1/2 × L × W2. Mice well-being and body weight changes were monitored daily. No obvious signs of toxicity were observed during treatment prior to reaching the end points in accordance to approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) protocols. The IACUC criteria for toxicity include 15% weight loss during the treatment.

Orthotopic model of LCC-6-MDR human triple-negative breast cancer model

Briefly, 100 μl of dispersion containing 5×106 LCC-6-MDR cells and 50% Matrigel were implanted into mammary fat pad of 6-week-old female nude mice using a 25 gauge needle. When tumor volumes reached about 200 mm3, animals were randomized into the groups of five and injected with the test articles using q4d x 4 regimen. The injected solutions were: 1) PTX/C6CP PM (40/3/50) (60 mg/kg PTX and 4.5 mg/kg C6CP); 2) PTX PM (40/50) and C6CP PM (3/50) mixture (60 mg/kg PTX and 4.5mg/kg C6CP); 3) PTX PM (40/50) (60 mg/kg PTX); 4) C6CP PM (3/50) (4.5 mg/kg C6CP); 5) 3 mg/kg cisplatin and 6) saline. Tumor volume and survival were monitored every other day. Mice were sacrificed when tumor reached volume of 2,000 mm3 or developed ascites metastasis.

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative results were expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical comparisons for drug release, PK, tumor accumulation, and tumor inhibition data were done using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Holm-Sidak post-hoc test for multiple comparisons. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 7.03 software. Statistical comparison of animal survival was done by Log-rank test. Differences were considered to be statistically significant if the p value was less than 0.05.

Pharmacokinetic Simulation

Simulation was used to evaluate the disposition of a drug, administered i.v. in the form of a PM micelle bolus. A three-compartmental model assuming first-order processes was developed using the computational modeling platform ADAPT5 [21]. Graphs were created in GraphPad Prism 7.02 for Windows, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA. Areas under the curve (AUCs) were computed using the trapezoidal rule. The simulated amounts of drug (in the tumor compartment) at various time points were evaluated to determine hypothetical maximum plasma concentrations, Cmax (assuming a volume of 1, with arbitrary units). The simulated elimination half-lives, t1/2 were determined using non-linear regression with least squares (ordinary) and robust fitting methods (GraphPad Prism 7.02).

Results

Preparation and characterization of PTX and CP loaded POx PM

The drug-containing PM were prepared using the thin film method as described in the experimental section. To prepare two drugs co-loaded PM we set the polymer concentration to a fixed value (10 g/L or 50 g/L) and examined different PTX and CP feed concentrations. Two ranges of the drug concentrations were evaluated (Table 1). In the first range the PTX and CP concentrations were kept relatively close to each other, PTX/CP/POx wt. ratios 1/3/10, 2/2/10 and 3/1/10. As a result, the PTX/CP molar ratios varied from ~0.2 to ~1.9 PTX/C6CP or ~0.25 to ~2.25 for PTX/C10CP, and were close to PTX/cisplatin dose ratios used in the clinical chemotherapy regimens [18]. The overall LC values in these PM formulations were high ~28 %, but not maximal for this PM system. In the second range, used for PTX/C6CP combination only, we kept the PTX concentration maximal and added smaller amounts of C6CP, so that the PTX/C6CP molar ratios varied from ~1.4 to ~15.8. As a result, the overall LC and the total drug concentration in these formulations were maximized reaching as much as ~46 % and ~43 g/L, respectively. In this case, we followed our recently published study on the high dose – high concentration PTX PM formulation that have shown extremely high anti-tumor activity in animal models [15]. In the context of the present work we were interested to determine whether addition of the cisplatin derivative to such high capacity formulation could further improve its anticancer efficacy.

Table 1 |.

Characteristics of PTX/CP PMa.

| Feeding ratio (g/L) |

LE (%) | LC (%) | Drug concentration in solution (g/L) | Deff(nm) | PDI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTX | CP | PTX | CP | PTX+CP | PTX | CP | PTX+CP | |||

| PTX/C6CP/POx | ||||||||||

| 1/3/10 | 100 | 99.7 | 7.2 | 21.4 | 28.6 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 86.4 ± 0.6 | 0.12 ± 0.05 |

| 2/2/10 | 100 | 100 | 14.3 | 14.3 | 28.6 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 79.7 ± 0.3 | 0.11 ± 0.07 |

| 3/1/10 | 100 | 100 | 21.4 | 7.14 | 28.4 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 54.2 ± 0.5 | 0.12 ± 0.01 |

| 20/3/50 | 99.3 | 92.7 | 27.3 | 3.8 | 31.1 | 19.9 | 2.8 | 22.7 | 34.2 ± 0.2 | 0.16 ± 0.01 |

| 20/5/50 | 92.9 | 33.5 | 26.4 | 2.4 | 28.8 | 18.6 | 1.7 | 20.3 | 35.7 ± 0.4 | 0.14 ± 0.01 |

| 45/1/50 | 81.1 | 100 | 41.7 | 1.2 | 42.2 | 36.5 | 1.0 | 37.5 | 74.2 ± 0.8 | 0.20 ± 0.01 |

| 45/2/50 | 85.8 | 100 | 42.6 | 2.2 | 44.8 | 38.6 | 2.0 | 40.6 | 69.7 ± 0.7 | 0.19 ± 0.01 |

| 45/3/50 | 89.6 | 100 | 43.2 | 3.2 | 46.4 | 40.3 | 3.0 | 43.3 | 66.4 ± 0.6 | 0.18 ± 0.01 |

| PTX/C8CP/POx | ||||||||||

| 1/3/10 | 100 | 96.3 | 7.20 | 20.8 | 28.0 | 1.00 | 2.89 | 3.89 | 110.4 ± 0.8 | 0.11 ± 0.01 |

| 2/2/10 | 100 | 98.5 | 14.3 | 14.1 | 28.4 | 2.00 | 1.97 | 3.97 | 97.8 ± 0.9 | 0.12 ± 0.01 |

| 3/1/10 | 100 | 100 | 21.4 | 7.14 | 28.54 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 68.7 ± 0.6 | 0.11 ± 0.02 |

| PTX/C10CP/POx | ||||||||||

| 1/3/10 | 100 | 92.3 | 7.26 | 20.1 | 27.36 | 1.00 | 2.77 | 3.77 | 141.4 ± 0.6 | 0.14 ± 0.03 |

| 2/2/10 | 100 | 94.5 | 14.4 | 13.6 | 28.0 | 2.00 | 1.89 | 3.89 | 121.8 ± 0.4 | 0.17 ± 0.02 |

| 3/1/10 | 100 | 97.0 | 21.5 | 6.94 | 28.44 | 3.00 | 0.97 | 3.97 | 99.2 ± 0.7 | 0.15 ± 0.02 |

Size (Deff) and PDI of POx polymeric micelles as measured by DLS. Drug concentration in solution as measured by HPLC. LE and LC calculated using equations (1)–(2) in the methods section. Drug solubilization studies were done at 10 g/L or 50 g/L POx. All DLS measurements were carried out at 1 g/L POx. All data mean ± SD, n=3.

The actual amount of the poorly soluble drug that incorporates into PM formulations is defined by the LE. As seen in Table 1 with almost all feed concentrations the LE for PTX was close to 100%, except for the very highly loaded micelle formulations, for which the PTX LE varied between ~80 % to ~90 %. As far as the incorporation CP is concerned it was nearly complete except for the PTX/C6CP PM (20/5/50), for which the LC decreased to ~33.5 %. Also, there appeared to be a consistent trend for different CP in the PM composition: as the length of the aliphatic tail in the cisplatin derivative increased, the LE for this derivative also decreased (Table 1).

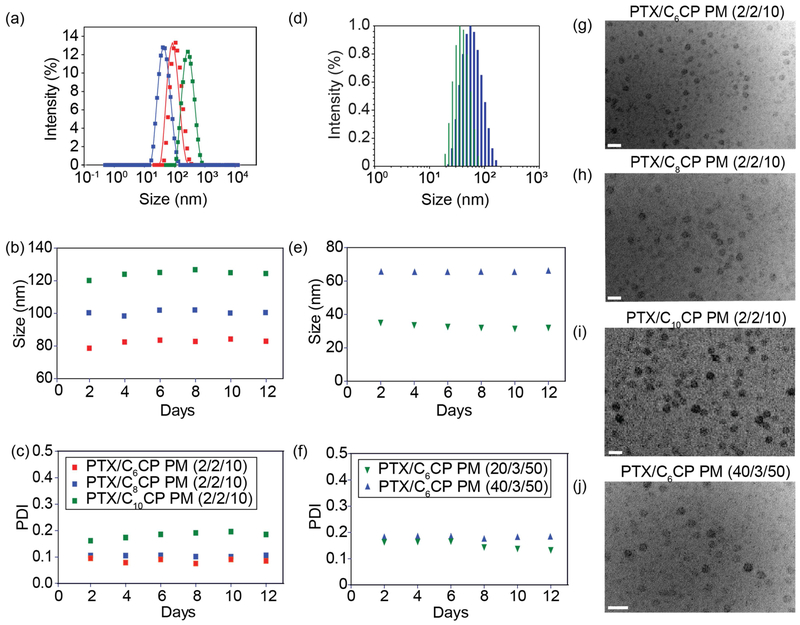

The particle sizes and PDI values varied, although in this case there was also a clear tendency for the particle size increase upon incorporation of increasing amount of CP (Table 1, Figure 1a–f). Moreover, at the same weight fraction of the CP the particle size appeared to become larger as the length of the alkyl chain increased (Table 1, Figure 1d). All prepared PM formulations remained quite stable in dispersion displaying little if any changes of the particle sizes and no drug precipitation for at least as long as 12 days (Figure 1b–f). No significant differences in the particle morphology was found between various PM as their shapes were nearly spherical by TEM (Figure 1g–j).

Figure 1 |. Physicochemical characterization of PTX/CP PM.

Size (Deff) distribution (a, d) and time dependence of size (b, e) and PDI (c, f) of PTX/CP PM measured by DLS. (a-c) PTX/C6CP (red), PTX/C8CP (blue), and PTX/C10CP [11] PM, all 2/2/10; (d-f) 20/3/50 [11] and 40/3/50 (blue) PTX/C6CP PM. The DLS measurements were done at 1 g/L POx. (g-j) TEM micrographs of PTX/C6CP (g, j), PTX/C8CP PM (h), and PTX/C10CP (i) PM. The TEM measurements were done at 10 g/L POx or 50 g/L POx. Scale bar = 100 nm.

The drug-loaded micelles were additionally characterized using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), energy dispersive X-ray spectrometry and proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) (Supplementary Figures S4–6). The XPS analysis suggests that the CP prodrug contains both Pt(IV) and Pt(II) ~76:24, which can be reduced by ascorbate to ~29:71. Incorporation of the prodrug in the PM micelles results in increase in the Pt(II) content to ~62:38, which may be due to partial reduction of the Pt(IV) during the rehydration step in the micelle preparation. However, even in the presence of major portion of PTX in PTX/C6CP PM (40/3/50) sample the prodrug remains mostly intact in the co-loaded micelles. This conclusion in reinforced by the 1H NMR analysis that did not reveal any chemical reactions between the CP (C6CP) and PTX during co-loading of the drugs in the micelles. Moreover, the co-loaded PTX and CP were quantitatively recovered by HPLC and each drug retention time was the same as that of the respective free drug analytical standard.

Drug co-loading in the PM slows down drug release compared to single-drug PM

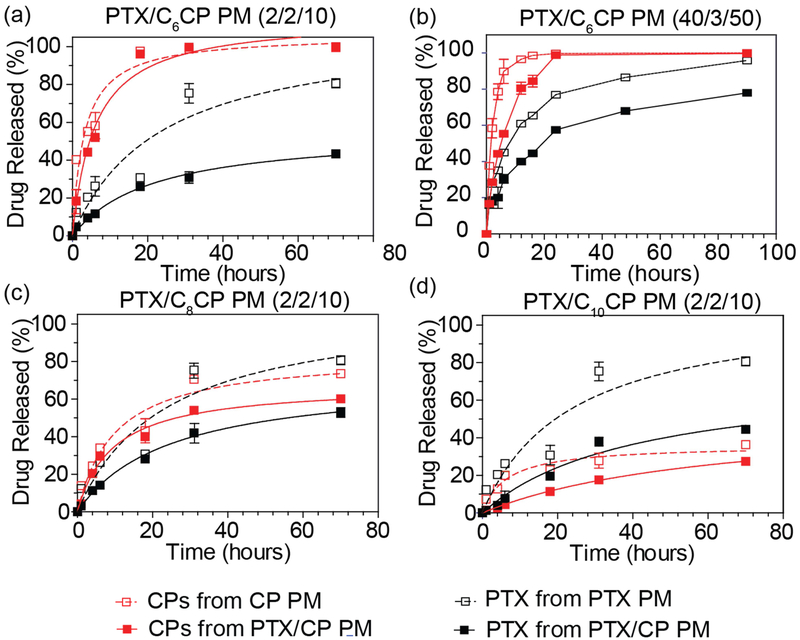

The drug release profiles of the PM were examined under sink conditions (Figure 2). For the CP containing micelles there was a clear trend observed - as the length of the aliphatic tail in the cisplatin derivative increased the rate of the release decreased. As a result while for C6CP was released faster than PTX form both single and combination drug micelle (Figure 2a,b) for the C8CP these rates were close to each other (Figure 2c), while for C10CP the situation was inverse and with this hydrophobic cisplatin derivative being released slower than PTX (Figure 2d). Strikingly, there was a clear evidence of drug-drug interactions in the micelle core as the release of both drugs from combination micelles was slower that their release from the single drug PM. This effect was the most pronounced for PTX in all combination formulations, was quite noticeable for high loaded PTX/C6CP PM as well as combination drug micelles containing two more hydrophobic cisplatin prodrugs (Figure 2).

Figure 2 |. Drug release profiles of PTX and CP from single and combination drug PM containing PTX and (a, b) C6CP, (c) C8CP and (d) C10CP.

The drug/polymer feed ratios were 2/2/10 (a, c, d) or 40/3/50 (b) for combination PM and 2/10 (a, c, d) or 40/50 and 3/50 (b) for single drug PM. The studies were performed at sink conditions at 37°C in PBS, pH 7.4 in the presence of 40 g/L BSA. Data are mean ± SD, (n=3)

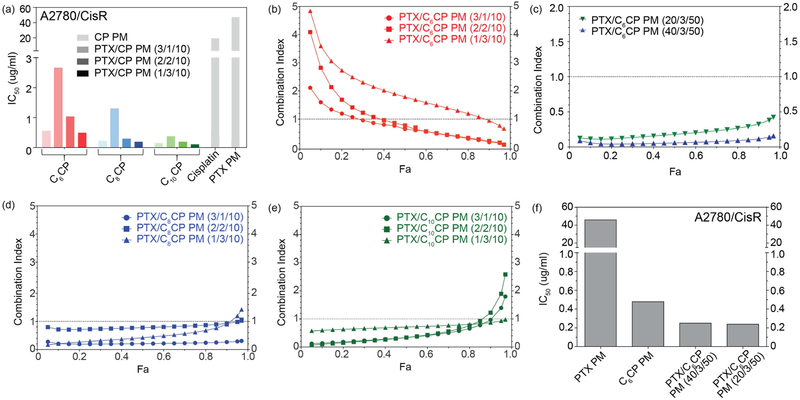

Drug combination micelles exhibit synergy in ovarian cancer cells

The cytotoxicities of the single and combination drug micelles was examined in two ovarian cancer cell lines one of which, A2780/CisR, was cisplatin-resistant and another, A2780, cisplatin-sensitive (Supplementary Figure S7). In the sensitive A2780 cell line, the IC50 values of single CP loaded PM were 0.309 μg/mL, 0.058 μg/mL and 0.045 μg/mL for C6CP, C8CP and C10CP PM, respectively, as compared to cisplatin of 1.141 μg/mL (Supplementary Figure S8). Therefore, the prodrug with the longer alkyl chain (C10CP) was ~30 times more toxic compared to cisplatin, while the prodrug with the shorter alkyl chain (C6CP) was only ~4 times more toxic. Same trend was observed in A2780/CisR cell line (Figure 3a). In this case the IC50 values were 0.546 μg/mL, 0.219 μg/mL, and 0.149 μg/mL for C6CP, C8CP and C10CP PM, respectively, as compared to cisplatin of 10.88 μg/mL. There was practically no difference in the cytotoxicity of the single PTX PM in these two cell lines with the IC50 values measuring 38.66 μg/mL and 47.36 μg/mL in the A2780 and A2780/CisR cells, respectively (Figure 3a).

Figure 3 |. In vitro cytotoxicity of PTX/CP PM in A2780/CisR human ovarian cancer cell lines.

(a, f) IC50 and (b-e) CI values of PTX/C6CP, PTX/C8CP and PTX/C10CP PMs. (a, e) For the combination drug micelles the IC50 values correspond to the total amount of both drugs.

In both cancer cell models the combination drug PM were substantially more active than either of the single drugs (Figure 3a,f, and supplementary Figure S8). Moreover, in all cases as content of the CP in the combination micelles increased in the cytotoxicity also increased. However, a consideration of the drug pharmacological synergy by the analysis CI using the isobologram equation of Chou–Talalay [22], suggested that the synergy strongly depends on the drug ratio. It is critical that the optimized doses and ratios of combined drugs are examined to promote synergistic rather than antagonistic effects [23]. In these cases, the CI values of less than 1, indicating drug synergy, were observed for PM with relatively high content of PTX and lower content of the cisplatin prodrug (Figure 3b–e, and supplementary Figure S8). In contrast, the compositions with relatively higher content of CP displayed CI values exceeding 1, suggesting antagonism of the two drugs. This trend was observed for each cisplatin derivative but was perhaps the most pronounced for the PTX/C6CP PM (Figure 3b,c). In this case we also compared five PM compositions with high and super-high drug loadings. The micelles with feed ratios 1/3/10 and 2/2/10 displayed no or minimal synergy, while the higher PTX content micelles 3/1/10 and high-loaded micelles 20/3/50 and 40/3/50 were showing pronounced and clear synergistic effect with CI value < 1 over a wider range Fa values from 0.1 to 1.0 (Figure 3b,c).

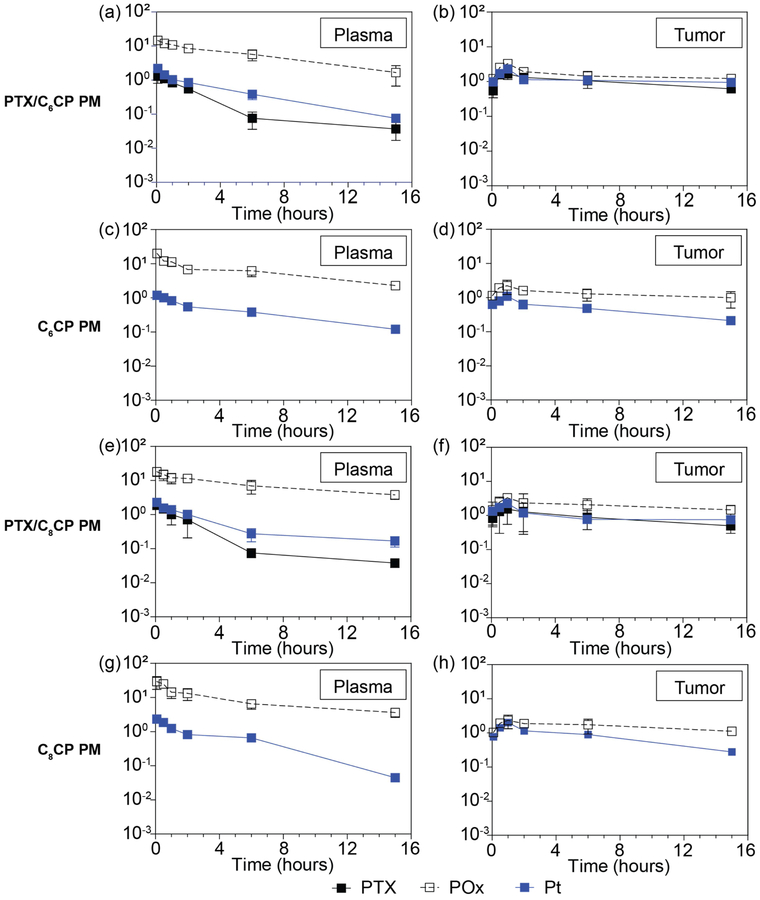

PK and tumor accumulation in A2780/CisR ovarian tumor bearing mice

The drug PK and distribution profiles for PTX/C6CP PM (2/2/10) and PTX/C8CP PM (2/2/10) at MTD were compared to those of the single drug micelles in A2780/CisR tumor bearing mice (Figure 4). The drug PK parameters calculated using a non-compartment model are presented in Tables 2 and 3. The PK parameters of the POx polymers for the same drug PM formulations are presented in the Supplementary Table S1. In the case of PTX/C6CP PM (2/2/10) it is apparent that the co-loading of C6CP and PTX in the PM increased the plasma half-life of each drug when compared to the respective single drug micelles (t1/2, α 7.67 h vs. 6.20 h for C6CP and 5.12 h vs. 3.67 h for PTX) (Table 2). Still the half-life of both drugs was less than that of the POx polymer alone (t1/2, α 12.6 h), which may indicate that the drugs are at least partially released from the circulating POx micelles. The Cmax in the plasma was increased ~2.0 fold for C6CP and ~1.4 fold for PTX, when compared to the single drug micelles. Moreover, there was ~1.9 fold increase in the plasma AUC of PTX (~1.5 fold decrease in CL) as well as ~1.3 fold increase Vdobs of this drug. At the same time, practically no changes in the plasma AUC and CL of C6CP was observed. In addition to the overall improved plasma PK the PTX/C6CP PM formulation also displayed considerable improvements in the tumor Cmax and AUC of both drugs as compared to the single drug PM. Specifically, the Cmax increased by ~2.3 fold for C6CP and ~1.6 fold for PTX (Table 2). The peak concentrations of both drugs in the tumors were observed at ~1 h post injection for all investigated formulations. The tumor AUC were increased ~2.9 fold for C6CP and ~1.3 fold for PTX.

Figure 4 |. PK and biodistribution in A2780/CisR human ovarian tumor bearing mice.

Plots of PTX, platinum (Pt) and POx concentrations in (a, c, e, g) plasma and (b, d, f, h) tumor over 15 h after single i.v. injection of co-loaded (a, b) PTX/C6CP PM (2/2/10), and (e, f) PTX/C8CP PM (2/2/10) as well as single drug loaded (c, d) C6CP PM (2/10) and (g, h) C8CP PM (2/10). Data are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 3 for all groups.

Table 2 |.

PK parameters of C6CP and PTX in plasma and tumor after administering PM in A2780/CisR tumor bearing mice.

| Parametersa | C6CP, 20 mg/kg | PTX, 20 mg/kg | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTX/C6CP PM | C6CP PM | Parameter ratio (PTX/C6CP PM : C6CP PM) |

PTX/C6CP PM | PTXPM | Parameter ratio (PTX/C6CP PM : PTX PM) |

||

| Plasma | t1/2, α (h) | 7.67 | 6.20 | 1.24 | 5.12 | 3.67 | 1.40 |

| Cmax (μg/mL) | 9.40 | 4.73 | 1.99 | 6.51 | 4.62 | 1.41 | |

| AUClast (h*μg/mL) | 34.80 | 30.00 | 1.16 | 18.41 | 9.78 | 1.88 | |

| C1obs (mL/h/kg) | 527.40 | 541.00 | 0.97 | 984.06 | 1434.66 | 0.69 | |

| Vdobs (mL/kg) | 5077.11 | 7963.56 | 0.64 | 10112.89 | 7689.6 | 1.32 | |

| Tumor | AUClast (h*μg/g) | 110.92 | 38.68 | 2.87 | 111.14 | 87.28 | 1.27 |

| Cmax (μg/g) | 9.86 | 4.34 | 2.27 | 8.34 | 5.38 | 1.55 | |

| Tmax (h) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

t1/2, α, half-life at the biodistribution phase; Cmax, maximum plasma concentration; AUClast, area under the curve from time 0 to 15 h; Clobs, observed total body clearance; Vdobs, total volume of distribution observed; Tmax, time of maximum concentration.

Table 3 |.

PK parameters of C8CP and PTX in plasma and tumor after administering PM in A2780/CisR tumor bearing mice.

| Parametersa | C8CP, 20 mg/kg | PTX, 20 mg/kg | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTX/C8CP PM | C8CP PM | Parameter ratio (PTX/C8CP PM : C8CP PM) |

PTX/C8CP PM | PTXPM | Parameter ratio (PTX/C8CP PM : PTX PM) |

||

| Plasma | t1/2, α (h) | 6.54 | 7.40 | 0.88 | 5.68 | 3.67 | 1.55 |

| Cmax (μg/mL) | 9.50 | 10.92 | 0.87 | 9.39 | 4.62 | 2.03 | |

| AUClast (h*μg/mL) | 37.23 | 45.89 | 0.81 | 21.69 | 9.78 | 2.22 | |

| Clobs (mL/h/kg) | 416.82 | 421.87 | 0.99 | 850.12 | 1434.66 | 0.59 | |

| Vdobs (mL/kg) | 6417.86 | 3066.92 | 2.09 | 8197.41 | 7689.6 | 1.07 | |

| Tumor | AUClast (h*μg/g) | 86.85 | 76.77 | 1.13 | 95.18 | 87.28 | 1.09 |

| Cmax (μg/g) | 9.38 | 9.34 | 1.00 | 7.74 | 5.38 | 1.44 | |

| Tmax (h) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

t1/2, α, half-life at the biodistribution phase; Cmax, maximum plasma concentration; AUClast, area under the curve from time 0 to 15 h; Clobs, observed total body clearance; Vdobs, total volume of distribution observed; Tmax, time of maximum concentration.

In case of PTX/C8CP PM, the effects of co-loading were less dramatic and seen mainly for PTX but not for C8CP (Table 3). In fact, for the co-loaded drug formulation the plasma half-life of C8CP was even slightly decreased when compared to the single drug micelles (t1/2, α 6.54 h vs. 7.40 h), although the half-life of PTX was still increased (t1/2, α 5.68 h vs. 3.67 h). Likewise, although there was a slight (~1.1 fold) decrease in the Cmax of C8CP in the plasma, the Cmax of PTX increased ~2.0 fold. The improvement in the PK of PTX in the PTX/C8CP PM formulation was further evidenced by ~2.2 fold increase in the plasma AUC of this drug (~1.7 fold decrease in CL) and slight (~1.1 fold) increase in the Vdobs. Again, the plasma AUC of C8CP in the co-loaded micelles was slightly decreased, although, surprisingly, these was almost ~2.1 fold increase in Vdobs. Consistent with the plasma PK, the Cmax of PTX in PTX/C8CP PM was increased ~2.0 fold while the Cmax of C8CP remained unchanged when compared to single drug micelles. Interestingly, the tumor AUCs for both C8CP and PTX in the PTX/C8CP PM (2/2/10) increased by only ~1.1 fold.

Further analysis suggests that the tumor to plasma AUC ratios for C6CP in the co-loaded drug micelles, PTX/C6CP PM (2/2/10), exceeded the same ratio for C6CP in the single drug micelles, C6CP PM (2/10), by only ~1.1 times (Supplementary Table S2). The similar tumor to plasma AUC ratio for PTX in co-loaded drug micelles exceeded the ratio for PTX in the single drug micelles by ~1.5 times. The tumor to plasma AUC ratios for C8CP in the co-loaded drug micelles, PTX/C8CP PM (2/2/10), exceeded the ratio for C8CP in the single drug micelles, C8CP PM (2/10), by ~1.4 times; and ~1.1 times exceeded for PTX. In other words, there is slight or considerable increase of the tumor delivery for each of the drugs in the co-loaded drug micelles.

Overall the co-loaded drug micelles displayed a considerably improved PK and biodistribution in the blood and tumor of either one or both drugs as compared to the single drug micelles. Analysis of the tumor PK parameters also suggests that the PTX/C6CP or PTX/C8CP ratios actually recorded in the tumor did not differ substantially from the drug ratios in the initial co-loaded drug micelle formulations. Thus, the tumor Cmax ratios were ~0.8 for both formulations, and the tumor AUC ratios were 1.0 and 1.1 for PTX/C6CP and PTX/C8CP, respectively. Therefore, one could expect that the delivered drugs would exhibit a synergistic anticancer effect on the tumor.

In vivo efficacy

The in vivo anti-tumor activity of the PM formulations was evaluated in the cisplatin-resistant human ovarian carcinoma xenograft A2780/CisR tumor model and multidrug resistant breast cancer LCC-6-MDR orthotopic tumor model. The animals were treated with the combination drug micelles, PTX/C6CP PM or PTX/C8CP PM, the single drug micelles or their mixture. In all experiments, the treatment groups also included free cisplatin. Since PTX PM have been previously consistently superior to the PTX formulations compared to Taxol and Abraxane (two nanoformulations being used in the clinic) [15] the latters were not included in treatment comparisons. All micellar drugs were administered at the MTD of either high or super-high loaded drug combination PM. The MTD values were determined in healthy 6–8 week old female nude mice using a q4d x 4 regimen. These MTD were 1) 20 mg PTX/kg and 20 mg CP/kg for PTX/CP PM (2/2/10), and 2) 60 mg/kg PTX and 4.5 mg/kg C6CP for PTX/C6CP PM (40/3/50). The MTD of the free cisplatin was 3 mg/kg.

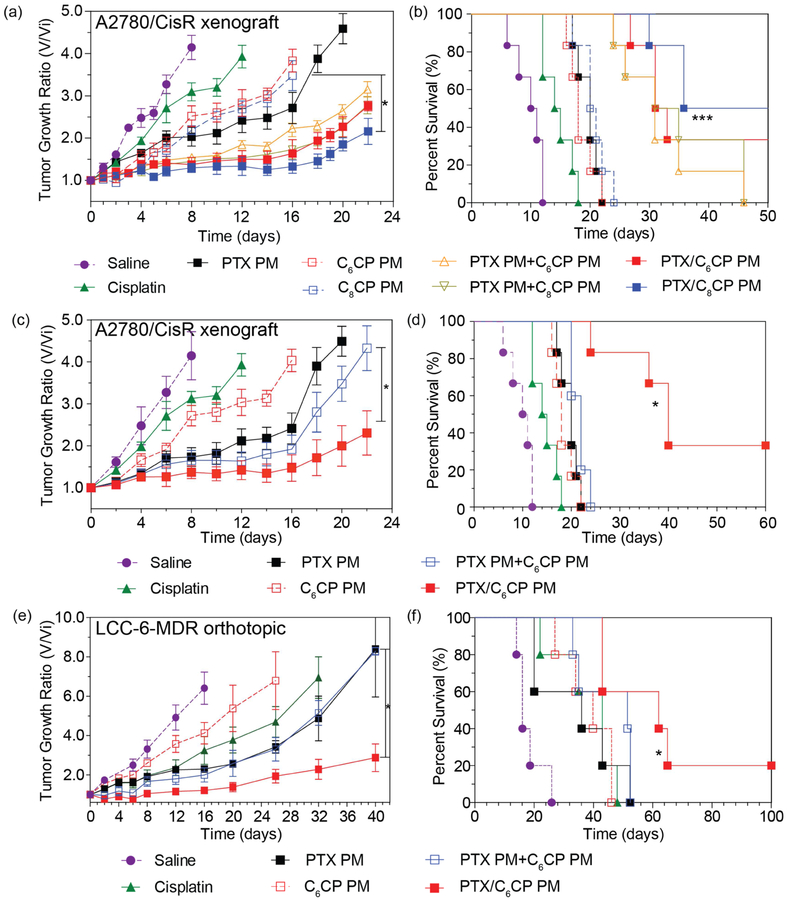

First, we compared the anti-tumor effects of PTX/C6CP (2/2/10) PM and PTX/C8CP (2/2/10) PM with the same doses of single drug micelles, PTX PM, C6CP PM and C8CP PM, or their mixtures in the A2780/CisR tumor model. This tumor is very aggressive and rapidly grows within the first week of the study, with the animals median lifespan of 10.5 days (Figure 5a,b). Free cisplatin had small but significant effect by delaying the tumor growth and extending the median lifespan to 14.5 days. The treatments with the single micelle drugs including PTX PM and both cisplatin prodrug forms, C6CP PM and C8CP PM resulted in a longer delay of the tumor growth and a significant increase in the median lifespan to ~18–20 days (see also Supplementary Tables S3 and S4). However, there was no statistical difference between any of the single drug PM groups. A major improvement in the anti-tumor treatment was observed with both combination drug PMs (PTX/C6CP (2/2/10) PM and PTX/C8CP (2/2/10) PM) which resulted in a pronounced tumor growth inhibition and a very significant increase of the median lifespan to ~46.5–55.4 days. It also has to be mentioned that in the co-drug loaded PM cohorts, 2 of 6 (PTX/C6CP (2/2/10) PM) and 3 of 6 (PTX/C8CP (2/2/10) PM) long-term survivors (beyond day 50) were observed. However, the differences between these two-combination drug micelle treatment groups in the tumor growth inhibition and animal lifespan were not significant. Interestingly, the co-loaded drug micelles, appeared to be more efficient than the mixtures of the single drug micelles PTX PM and C6CP PM (or C8CP PM). No long-term survivors were observed for any of the studied single drug micelles mixture (Figure 5b). While the differences in the tumor inhibition between these groups were not significant, the co-loaded PTX/C8CP PM group had a statistically higher lifespan than the respective PTX PM and C8CP PM single drug mixture (Tables S3 and S4).

Figure 5 |. Anti-tumor effects of the single and combination drug polymeric micelles in the (a-d) cisplatin-resistant human ovarian carcinoma xenograft A2780/CisR tumor and (e, f) multidrug resistant breast cancer LCC-6-MDR orthotopic tumor models.

(a, c, e) Tumor volume changes and (b, d, f) Kaplan-Meier survival plots. The treatments regimen was q4d x 4. Drug injection doses were: (a, b) 20 mg PTX/kg and/or 20 mg CP/kg for PTX/C6CP PM (2/2/10), PTX/C8CP PM (2/2/10), PTX PM (2/10) and C6CP PM (2/10) mixture, PTX PM (2/10) and C8CP PM (2/10) mixture, PTX PM (2/10), C6CP PM (2/10) and C8CP (2/10) PM; (c-f) 60 PTX mg/kg and/or 4.5 C6CP mg/kg for PTX/C6CP PM (40/3/50), PTX PM (40/50) and C6CP PM (3/50) mixture, PTX PM (40/50), C6CP PM (3/50); (a-f) and 3 mg/kg cisplatin. (a, c, e) Data are mean ± SD, n = 5. (a-f) * p<0.05. *** p<0.001, (n = 6 (a-d) or 5 (e, f)). For detailed statistical comparisons see Supplementary Tables S3 and S4.

Next, we examined the treatments effects of a super-high drug loaded combination micelle, PTX/C6CP PM (40/3/50). In this case along with the free cisplatin and single drug micelles we also examined a mixture of single drug-loaded micelles, PTX PM (40/50) and C6CP PM (3/50) that were administered simultaneously and at the same drug doses as the combination micelles. Interestingly, C6CP PM (3/50), had a similar effect on the tumor growth and animal lifespan as C6CP PM (2/10) administered in the above study at ~4.4-times higher dose of the cisplatin prodrug (Figure 5c,d). However, in this case the difference between the free drug and C6CP PM (3/50) in tumor growth curves was not significant (Supplementary Table S3). The treatment with PTX PM (40/50) had the greatest effect of the single drug micelles both in the tumor growth inhibition and the increased lifespan. Surprisingly, however, the two single drug micelles mixture PTX PM (40/50) and C6CP PM (3/50) did not exhibit statistically significant improvement compared to PTX PM (40/50) alone (Figure 5c,d). In contrast, the same dose of the two drugs co-formulated together PTX/C6CP PM (40/3/50) had a profound therapeutic effect superior to any of the other treatment or control groups. Like in the previous case of combination drug micelles these effects were not only statistically significant but also resulted in 2/5 long-term survivors (beyond day 60).

Finally, to validate the observed phenomena, we evaluated same treatment regimens in the MDR LCC-6-MDR orthotopic tumor model. It has been previously reported that Taxol at MTD is not therapeutically active in this model [14]. Surprisingly, however, cisplatin alone (3mg/kg) produced considerable antitumor effect, which was superior in this case to the single drug micelles carrying the cisplatin prodrug, C6CP PM (3/50) (Figure 5e,f). Like in the previous case PTX PM (40/50) had a somewhat greater effect by decreasing the tumor growth rate compared to any other single drug group but this effect was not significant and neither were the difference in the lifespan compared to these treatment groups. Like in the previous case, the effects of the two single drug micelles mixture PTX PM (40/50) and C6CP PM (3/50) on the tumor growth were practically indistinguishable from that of the PM (40/50). The combination drug micelles PTX/C6CP PM (40/3/50) had the greatest effect surpassing any of the treatment groups in both the inhibition of the tumor growth and in the prolongation of the lifespan to a median of (Figure 5e,f, Supplementary Tables S3 and S4). In this treatment group, there was 1/5 long-term survivor (beyond day 100).

PK modeling of micellar drug distribution to tumor

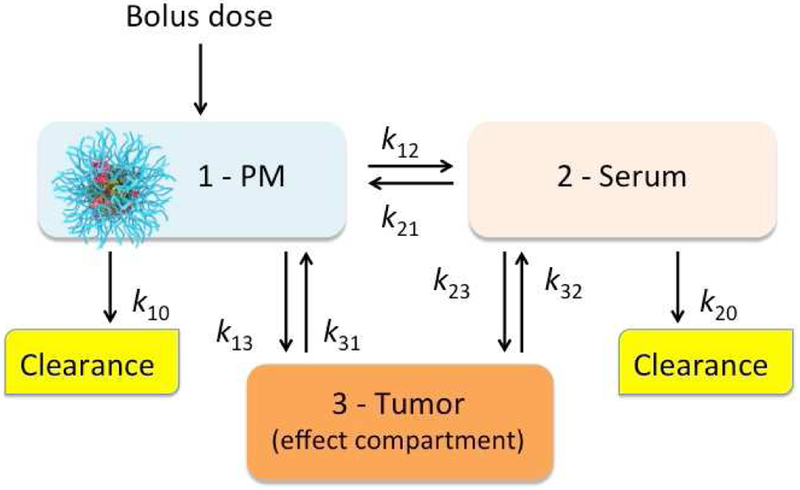

Assuming that the antitumor efficacy of a drug is directly related to the amount of this drug delivered to the tumor, we conducted PK modeling to estimate effects of various parameters on the tumor distribution of the micellar drugs. The assumptions made during this analysis are summarized in Figure 6. The models were simulated under the two basic scenarios: A – the tumor permeability of the micellar drug is much less than that of the serum-bound drug (k13 ≪ k23); and B - the tumor permeability of the micellar and serum-bound drug is similar (k13 = k23). For both scenarios we assume that the clearance rate of the serum-bound drug is much faster than that of the drug in PM (k10 ≪ k20), which is generally consistent with our previous data comparing PK of PTX POx PM and Taxol that rapidly releases drug to the serum [15].

Figure 6 |. A three-compartmental model describing the PM drug delivery to a tumor.

The drug is administered as bolus in the form of PM (1) and is subsequently distributed between the serum (2) and tumor (3) compartments. The PK constants correspond to: k12 - rate of drug transfer from PM to serum; k21 - rate of drug re-capture from serum to PM; k13 - rate of transfer (permeability) of the micellar drug to tumor; k23 - rate of transfer of the serum-bound drug to tumor; k31 and k32 – rates of drug reabsorption from tumor to PM and serum, respectively; k10 and k20 - micellar and serum-bound drug clearances, respectively. The model assumes that the drug solubility in blood is very low and the free drug form in the blood is therefore neglected.

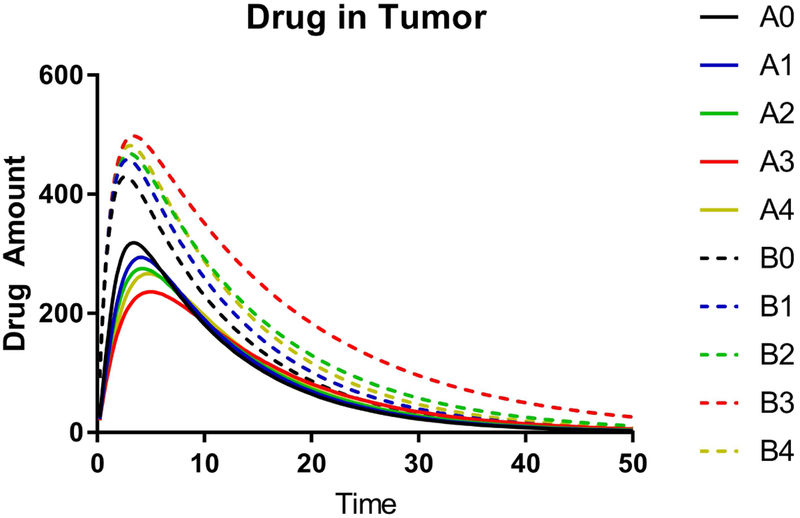

In each scenario the parameters corresponding to the distribution of the drug between different compartments were varied to elucidate influence of these parameters in each compartment (Supplementary Table S8). Specifically, for each basic model we considered cases in which the retention of the drug in the micelles vs. its binding to the serum was altered. This was achieved by altering the rate of release from the PM to serum, k12, and the rate of reabsorption to PM from the serum-bound state, k21. In both basic scenarios the concentration profiles and AUC values for PM compartment increase and the respective values for the serum-bound drug compartment decrease as the retention of the drug in the micelles increases (Table 4, Supplementary Figure S9). This pattern is seen 1) when the rate of the micellar drug transfer to serum decreases (A0 vs. A1, or A4; B0 vs. B1, or B4), or 2) when the rate of reabsorption to micelles increases (A1 vs. A2; B1 vs. B2), or 3) when both parameters are correspondingly altered (A0 vs. A3; B0 vs. B3). However, there is a drastic difference in the results for the tumor compartment between the basic scenarios A and B (Table 4, Figure 7). When the micellar drug permeability to the tumor is much less than that of the serum bound drug (scenario A) the effects of alteration of the drug retention in the micelle upon the tumor AUC are negligible (less than 0.024 % of the calculated AUC value), although some changes in the shape of the drug concentration curves in the tumor are observed. In contrast, when the micelles and serum protein permeability to the tumor are comparable (scenario B) the increase of the retention of the drug in the micelles results in a strong increase in the drug accumulation in the tumor. The different scenarios in our model also exhibit diverging trends in the tumor Cmax values. Specifically, as the drug retention in the micelles increases, Cmax decreases in scenario A, but increases in scenario B. Therefore, for the model and assumptions used here the micelle permeability to the tumor is the decisive parameter for the drug distribution to the tumor compartment. In contrast, in both basic scenarios A and B the half-lives increase as drug retention in the micelles increases. This trend is observed for every compartment: micelles, serum, tumor, as well as the total drug concentration in blood (the micelle and serum compartments combined) (Supplementary Table S6). The trend is a result of a lower micelle vs. serum clearance rates assumed and it appears to be consistent with the experimental data in Table 2 and 3 for PTX and C6CP.

Table 4 |.

AUC values calculated for the three-compartmental model presented in Figure 6.

| Compartment | AUC (arbitrary units)a | ||||

| Basic scenario A (k13 << k23) | |||||

| A0 | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | |

| (1) Micellar drug | 945.5 | 1714 | 2524 | 4685 | 2718 |

| (2) Serum-bound drug | 1757 | 1611 | 1449 | 1022 | 1414 |

| (3) Drug in Tumor | 4165 | 4165 | 4165 | 4165 | 4165 |

| Compartment | Basic scenario B (k13 = k23) | ||||

| B0 | B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | |

| (1) Micellar drug | 712.5 | 1121 | 1736 | 3047 | 1520 |

| (2) Serum-bound drug | 1806 | 1732 | 1610 | 1356 | 1656 |

| (3) Drug in Tumor | 5625 | 6323 | 7353 | 9563 | 6997 |

Arbitrary numerical value of AUC from 0 to infinity. The parameters used in the calculation are shown in Supplementary Table S5. The PK time profiles are presented in Supplementary Figure S9.

Figure 7 |. The drug amount-time profiles for the tumor obtained using a three-compartmental model.

Simulations for basic scenarios A (solid lines) and B (dashed lines) are shown. The three-compartmental model is presented in Figure 6 and the values of the PK parameters used in simulation are listed in Supplementary Table S8. The complete drug amount profiles for all three compartments are shown in Supplementary Figure S9. All units are arbitrary.

Discussion

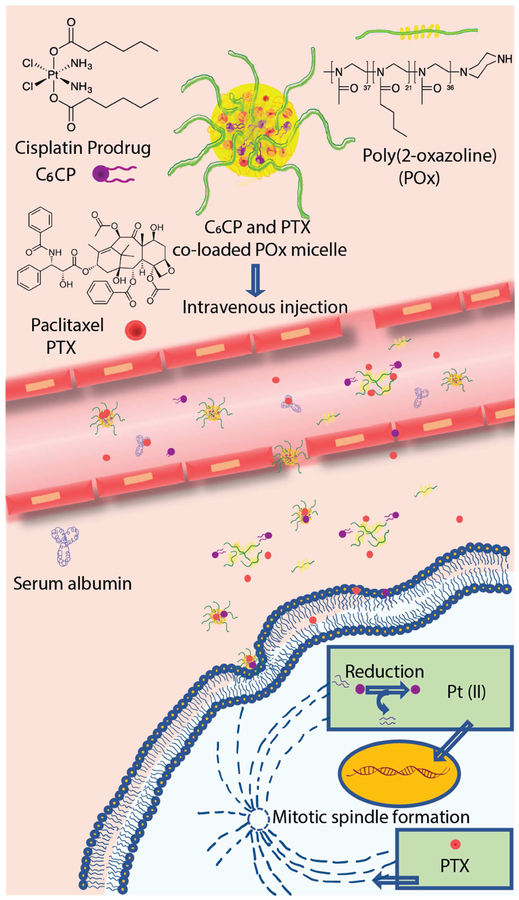

The strategy employing the POx micelles for the co delivery of the PTX and CP prodrugs is schematically presented in Figure 8. In this study, we co-loaded PTX and CP in POx micelles resulting in the micellar formulations with LC from ~28 % to ~46 % of the total drug in the dispersed phase, and the total drug concentration in the solution from about 3 g/L to over 40 g/L. We also varied the PTX and CP ratios (wt.) in a broad range from excess of CP vs. PTX (3:1) to a considerable excess of PTX vs. CP (45:1). In most cases, except for the very highly drug (PTX) loaded systems, both drugs incorporated in the PM nearly completely (LE ~100%). The nanoparticles in the obtained formulations were small, mostly uniform (PDI 0.11 to 0.2), and stable upon storage for over 12 days. We did not observe any chemical reaction between PTX and CP in the co-formulated micelles. However, the process of incorporation of CP in the micelles would need to be optimized in the future as Pt(IV) appears to be partially reduced to Pt(II) during preparation of the samples. Unexpectedly, we discovered that co-loading of the drugs in the micelles slowed down the release of these drugs, especially PTX, to the external media containing serum albumin when compared to the release rates observed with the single-drug PM.

Figure 8 |. The strategy using POx micelles for the co-delivery of PTX and CP prodrug.

Due to the very good miscibility of both drugs in the POx PM systems, we were able to analyze the pharmacological synergy of the drugs at different ratios as assessed by the CI values in the cisplatin-resistant and cisplatin-sensitive breast cancer cells. There was a trend for the synergy enhancement upon increase of the relative content of PTX vs. CP. The most pronounced drug synergy was observed in the very high PTX-loaded micelles, PTX/C6CP PM (40/3/50). This was one formulation selected for the animal efficacy studies. The two other formulations evaluated in the animal models were PTX/C6CP PM (2/2/10), and PTX/C8CP PM (2/2/10), containing two different cisplatin derivatives. Since the drug synergy displayed by these formulations in the cell culture was moderate to high (depending on the cell model), a possible shift in the concentrations of the drugs that would actually reach tumors could be of potential concern for treatment. Therefore, we characterized the PK and tumor distribution of both drugs in these formulations in the animal model of drug-resistant ovarian cancer. Surprisingly, based on the PK data the resulting PTX/C6CP or PTX/C8CP ratios in the tumor did not differ substantially from the drug ratios in the initial co-loaded drug micelle formulations. Consistent with this, the efficacy studies suggested that these co-loaded micelles are superior to any of the single drug micelle formulation and even the mixture of the single drug micelles administered at the same dose. In the tumor treatment study, the drug doses used in a mouse were 20 mg/kg PTX and ~11.1 mg/kg cisplatin equivalent (PTX/C6CP PM (2/2/10)) or ~10.2 mg/kg cisplatin equivalent (PTX/C8CP PM (2/2/10)). When recalculated to the human equivalent dose (HED) based on the body surface area [24] these doses corresponded to ~60 mg/m2 (~1.6 mg/kg) for PTX and ~31–33 mg/m2 (~0.83–0.89 mg/kg) for cisplatin, which is approximately half of the doses used in clinic for the PTX (135 mg/m2) and cisplatin (75 mg/m2) combination [18]. Even more striking effects of the co-loading of the drugs on the anti-tumor activity of the PM formulation were observed for the highly loaded PTX/C6CP PM (40/3/50) in drug resistant ovarian and breast cancer models. In this case the treatment doses in a mouse were 60 mg/kg for PTX and ~2.55 mg/kg for cisplatin equivalent, which correspond to HED of ~180 mg/m2 (~4.8 mg/kg) for PTX and ~7.5 mg/m2 (~0.89 mg/kg) for cisplatin. The HED of PTX is therefore very similar to the clinical dose of Taxol (175 mg/m2) [25]. The results suggest a possibility of developing a novel high capacity PM combination drug regimen of PTX combined with low dose of cisplatin, which is superior to high capacity PTX PM micelles alone [15].

Overall, the data provide support of the beneficial effect of co-loading of drugs into the micelles as a strategy for improved chemotherapy. Several prior studies have reported the nanoformulations simultaneously containing PTX and cisplatin, including formulations based on polymeric micelles formed by amphiphilic block copolymers [26–28], mesoporous carbon-silica nanospheres [29], and prodrug hydrogels [30]. Although some of these studies demonstrated a synergistic effect of two drugs in vitro, and in select cases superior anti-tumor effect of co-formulated two drugs compared to single drugs in vivo, the reported systems have constrains due to different mechanisms of drug loading. Compared to POx PM in our study, these systems displayed considerably lower drug loadings and less flexibility in changing the drug ratio, which is essential for optimizing synergistic drug combinations. The simplicity of our approach based on simple mixing of the components along with the ultra-high loading capacity of POx micelles provides in our view advantages for clinical translation. A drastic efficacy enhancement of the co-loaded drug POx micelles compared to same drugs mixture observed in this study in vivo is highly promising for the development of novel drug therapies.

To understand the underlying mechanism for the observed efficacy increases we compared the PK of co-loaded drugs to the single drug micelles. The results were quite insightful and suggested an overall improvement of the PK and distribution of both drugs as a result of their co-loading in one PM system. Specifically, there were increases in the plasma half-life, Cmax, AUCs, and decreases in the clearance of both drugs observed for the co-loaded micelles PTX/C6CP PM (2/2/10), containing a relatively less hydrophobic cisplatin derivative, C6CP. There was also a considerable improvement in Cmax and AUC of both drugs in the tumor. Notably, the ICP-MS technique used for determination of CP prodrugs in PK studies does not distinguish between different forms of platinates. In the case of the co-loaded micelles PTX/C8CP PM (2/2/10), containing a relatively more hydrophobic cisplatin derivative C8CP, improved plasma PK was observed for PTX only, but not for C8CP. Likewise, the improvement in drug delivery to the tumor using co-loaded micelles PTX/C8CP PM (2/2/10) was less pronounced when compared with PTX/C6CP PM (2/2/10). However, a detailed analysis of the PK data suggests that the apparent differences in the effect of the co-loading for the drug pairs are a result of the difference in the PK behavior of the single drug micelles, C6CP PM (2/10) and C8CP PM (2/10), rather than that of the co-loaded micelles. Indeed, C8CP PM (2/10) appears to have considerably higher Cmax and AUC both in plasma and in tumor when compared with C6CP PM (2/10), while the PK parameters of the respective drugs in PTX/C8CP PM (2/2/10) and PTX/C6CP PM (2/2/10) are similar.

Interestingly, the rates of release of relatively more hydrophobic C8CP from both single drug and co-loaded drug micelles are nearly twice lower than those of the less hydrophobic C6CP. Thus, it is tempting to suggest that the differences in the PK appear to correlate with the drug release results. Specifically, a decrease in the release rate of C6CP observed as a result of co-loading of this drug with PTX may be responsible for a relatively better retention of C6CP in the co-loaded micelles in plasma and improvement in the plasma and tumor PK as result of co-loading. In contrast, the retention of C8CP in either co-loaded or single drug micelles is relatively good, and therefore the differences in the PK for this drug in the co-loaded and single drug micelles are attenuated.

The relationship between the drug release kinetics from the nanoparticles and the therapeutic efficacy and toxicity of the drugs delivered using these nanoparticles has been previously reported [31]. For nanoparticles having same size, shape and surface charge a decrease in the rates of release of drugs (docetaxel, wortmannin) was accompanied by an increase in the anti-tumor effects in vivo. It was also reported that a decrease in drug release kinetics was accompanied by a decrease in the hepatotoxicity of CLS NP wortmannin. However, the relationship of the drug release rate and the PK and tumor distribution of micellar drugs has been relatively less explored. Our recent study reported that co-loading of etoposide and C6CP in POx micelles resulted in considerable decrease in the release rates and increase in the tumor distribution of both drugs along with the increased anticancer activity of the co-loaded formulation compared to the single drug micelles [20]. However, in that study the co-loading also resulted in a drastic change of the particles shape, which has complicated dissecting the effect of the release kinetics. Our present work reinforces that altering the release rates by co-loading two drugs in one micelle is one possible way of increasing drug distribution to the tumor and improving the anti-tumor effect in vivo.

Since micelles are dynamic structures they are expected to exchange their components with the environment. Specifically, the block copolymer chains are partitioned between the micelles and external solution (individually dissolved block copolymer chains or unimers), while the hydrophobic drugs, such as PTX and CP, are partitioned between the micelles and serum proteins present in the blood. As a result, complex equilibriums should establish in a steady state condition, although an existence of any such equilibrium in the body should not be assumed automatically, because the redistribution of the solutes between the PM and environment could be quite slow [32]. As the concentration of the components of the PM in the circulation decreases due to their clearance, the equilibriums are expected to shift. Thereby the PK of each component that is redistributed between various circulating formats (micelles, unimers for POx chains, serum-bound drugs) should be an integral result of the PK properties of an individual format as well as their redistribution kinetics. Despite of the obvious complexity of the resulting picture, it is possible to dissect some individual formats behavior from the PK data. For example, our previous study of the plasma PK and biodistribution of Pluronic P85 was carried out at the critical micelle concentration (CMC), when only unimers were present, and well above this concentration, when both unimers and micelles were present [33]. It was discovered, that clearance was independent on the concentration, which was indicative of the renal clearance of the unimers but not the micelles (that were above the renal clearance limit).

With this consideration in mind, comparing the PK results for the drugs and POx block copolymers can provide further insight into the behavior of the drug-containing micelles in vivo. As already mentioned the drugs plasma half-life even in the co-loaded micelles (when the drug half-life was increased compared to the single drug micelles) was less than that of the POx copolymer. That means that the drugs were cleared faster than the micelles and suggests at least partial release of the drugs from the micelles to serum proteins. Moreover, Vdobs of the drugs was from about 7.5- to about 27-fold higher than the Vdobs of the POx copolymer. A drastic, 5- to 20-fold difference in the Tumor AUC/Plasma AUC and Tumor Cmax/Plasma Cmax ratios between the drugs and POx copolymer also suggests that the drugs are partitioned to the tumor more efficiently than the copolymer. One possible explanation is that the drug molecules are transferred to the serum proteins and then accumulate in the tumors, perhaps, in a serum-bound state, along with the micelles that can also carry the drug to the tumor. There is no doubt that the serum bound drug is active upon tumors as the release of the drug, in particular PTX, to the serum is a putative mechanism of the anti-tumor activity of Taxol [34], and another blockbuster PTX-based drug, Abraxane, represents the complex of PTX with serum albumin [35].

This hypothesis on a surface is counterintuitive. On one hand, based on our data, the stronger the drug is retained in the micelles, the greater the plasma exposure is, and the greater the tumor accumulation of this drug is. On the other hand the drug appears to be delivered to the tumor, at least in part separately from the micelles. However, one needs to appreciate that sustained circulation of the drug in the form of the micelles, with continuous transfer of the drug molecules to the serum proteins (and possibly back to the micelles), also enhances the overall exposure of the tumor to both serum-bound and micelle-bound formats combined. To illustrate this phenomenon, we carried out a PK simulation for a three-compartmental model under a simplified assumption that the micelles are stable and do not disintegrate to unimers. The results of the simulation suggest that an increase of the retention of a drug in the micelle can indeed result in an increase in the overall amount of the drug in the tumor compartment, albeit only in the case when the permeability of the micellar and serum-bound drugs to the tumor are comparable. This conclusion is consistent with the prior studies suggesting that the tumor permeability as the well as the size of the nanoparticles (including polymeric micelles of different type) are critically important for nanoparticle drug distribution to tumors and the resulting anticancer effects [36–38].

Conclusion

We describe the PTX and cisplatin co-loaded in POx micelle formulations for combination therapy of tumors. This micellar system displays a broad range of drug mixing ratios and exceptionally high two-drug loading as well as the slowed-down release of the drugs to the serum as a result of their co-loading. Simulations of PK for the micelle, serum and tumor compartments in a three compartmental model suggest that the decreased rates of drug release from the micelles to the serum can result in improved tumor drug delivery provided that the micelles display high enough ability to penetrate in the tumor. The improved PK and increased tumor distribution for both drugs as a result of their formulation in one micelle is demonstrated for the animal tumor model. The superior performance of these formulations in vivo is further reinforced by an increased anti-tumor efficacy in breast and ovarian cancer models. The demonstrated superior efficacy of the PTX and cisplatin co-loaded micelles suggests that co-loading of drugs is one strategy for improved chemotherapy of cancer and the researched formulations may hold promise for the further translational development.

Supplementary Material

Table 5 |.

Tumor Cmax values calculated for the three-compartmental model presented in Figure 6.

| Compartment | Cmax (arbitrary units) a | ||||

| Basic scenario A (k13 << k23) | |||||

| A0 | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | |

| (3) Drug in Tumor | 318.8 | 294.1 | 275.4 | 236.3 | 266.9 |

| Compartment | Basic scenario B (k13 = k23) | ||||

| B0 | B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | |

| (3) Drug in Tumor | 429.5 | 458.5 | 468.4 | 498.1 | 481.9 |

Numerical value of Cmax with arbitrary units. The parameters used in the calculation are shown in Supplementary Table S8. The PK time profiles are presented in Supplementary Figure S9.

Acknowledgement:

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Alliance for Nanotechnology in Cancer (U54CA198999, Carolina Center of Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence). A.Z.W. was also supported by NCI (R21 CA182322). X.W. is grateful to the China Scholarship Council (CSC) for a pre-doctoral fellowship (2011601254). We also acknowledge Charlene Santos at MP1U of UNC for helping the development of the orthotopic breast cancer model and Nanomedicines Characterization Core (NCore) for ICP-MS measurements; Zibo Li and Hui Wang for designing and performing the 64Cu labeling of POx and assistance with the data analysis; William Zamboni for advice and oversight in PK calculations and analysis. The XPS and EDS studies were performed by Carrie Lynn Donley and Wallace W Ambrose respectively at the Chapel Hill Analytical and Nanofabrication Laboratory, CHANL, a member of the North Carolina Research Triangle Nanotechnology Network, RTNN, which is supported by the National Science Foundation, Grant ECCS-1542015, as part of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure (NNCI). AVK and RJ are listed as inventors on patents pertinent to the subject matter of the present contribution and co-founders of DelAqua Pharmaceuticals Inc. having intent of commercial development of POx based drug formulations.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Ozols RF, Advanced ovarian cancer: a clinical update on first-line treatment, recurrent disease, and new agents, J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2 (2004) S60–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Rhee EJ, Jeong HS, and Lee SS, Efficacy of Combination Chemotherapy with Paclitaxel and Cisplatin in Patients with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Cancer Res Treat 34 (2002) 28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Schiff PB, Fant J, Horwitz SB, Promotion of microtubule assembly in vitro by taxol, Nature 277 (1979) 665–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Florea AM, Busselberg D, Cisplatin as an anti-tumor drug: cellular mechanisms of activity, drug resistance and induced side effects, Cancers (Basel) 3 (2011) 1351–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Siddik ZH, Cisplatin: mode of cytotoxic action and molecular basis of resistance, Oncogene 22 (2003) 7265–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hall MD, Telma KA, Chang KE, Lee TD, Madigan JP, Lloyd JR, et al. , Say no to DMSO: dimethylsulfoxide inactivates cisplatin, carboplatin, and other platinum complexes, Cancer Res. 74 (2014) 3913–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lancet JE, Uy GL, Cortes JE, Newell LF, Lin TL, Ritchie EK, et al. , Final results of a phase III randomized trial of CPX-351 versus 7+ 3 in older patients with newly diagnosed high risk (secondary) AML, American Society of Clinical Oncology 34 (2016) 7000. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Qin M, Koo Lee YE, Ray A, Kopelman R, Overcoming cancer multidrug resistance by codelivery of doxorubicin and verapamil with hydrogel nanoparticles, Macromol Biosci.14 (2014) 1106–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ma L, Kohli M, Smith A, Nanoparticles for combination drug therapy, ACS Nano 7 (2013) 9518–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Tian J, Rodgers Z, Min Y, Wan X, Qiu H, Mi Y, et al. , Nanoparticle delivery of chemotherapy combination regimen improves the therapeutic efficacy in mouse models of lung cancer, Nanomedicine 13 (2017) 1301–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Leonessa F, Green D, Licht T, Wright A, Wingate-Legette K, Lippman J, et al. , MDA435/LCC6 and MDA435/LCC6MDR1: ascites models of human breast cancer, 73 (1996) 154–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Luxenhofer R, Han Y, Schulz A, Tong J, He Z, Kabanov AV, et al. , Poly(2-oxazoline)s as polymer therapeutics, Macromol Rapid Commun. 33 (2012) 1613–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Han Y, He Z, Schulz A, Bronich TK, Jordan R, Luxenhofer R, et al. , Synergistic combinations of multiple chemotherapeutic agents in high capacity poly(2-oxazoline) micelles. Mol Pharm. 9 (2012) 2302–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].He Z, Schulz A, Wan X, Seitz J, Bludau H, Alakhova DY, et al. , Poly(2-oxazoline) based micelles with high capacity for 3rd generation taxoids: preparation, in vitro and in vivo evaluation, J. Control. Release 208 (2015) 67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].He Z, Wan X, Schulz A, Bludau H, Dobrovolskaia MA, Stern ST, et al. , A high capacity polymeric micelle of paclitaxel: Implication of high dose drug therapy to safety and in vivo anti-cancer activity, Biomaterials 101 (2016) 296–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dhar S, Gu FX, Langer R, Farokhzad OC, Lippard SJ, Targeted delivery of cisplatin to prostate cancer cells by aptamer functionalized Pt(IV) prodrug-PLGA-PEG nanoparticles, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 105 (2008) 17356–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bijnsdorp IV, Giovannetti E, Peters GJ, Analysis of Drug Interactions, in Cancer Cell Culture: Methods and Protocols, Cree IA (Editor), Humana Press: Totowa, NJ: 2011, pp. 421–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Rosati G, Riccardi F, Tucci A, De Rosa P, Pacilio G, A phase II study of paclitaxel/cisplatin combination in patients with metastatic breast cancer refractory to anthracycline-based chemotherapy, Tumori. 86 (2000) 207–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chou TC, Talalay P, Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors, Adv. Enzyme Regul. 22 (1984) 27–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wan X, Min Y, Bludau H, Keith A, Sheiko SS, Jordan R, et al. , Drug Combination Synergy in Worm-like Polymeric Micelles Improves Treatment Outcome for Small Cell and Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, ACS Nano 12 (2018) 2426–2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].D’Argenio DZ, Schumitzky A, A program package for simulation and parameter estimation in pharmacokinetic systems, Comput, Programs Biomed, 9 (1979) 115–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chou TC, Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the Chou-Talalay method, Cancer Res. 70 (2010) 440–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Miao L, Guo S, Zhang J, Kim WY, Huang L, Nanoparticles with Precise Ratiometric Co-Loading and Co-Delivery of Gemcitabine Monophosphate and Cisplatin for Treatment of Bladder Cancer, Adv. Funct. Mater 24 (2014) 6601–6611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].FDA, Guidance for Industry, Estimating the Maximum Safe Starting Dose in Initial Clinical Trials for Therapeutics in Adult Healthy Volunteers in: U.S.D.o.H.a.H. Services, F.a.D. Administration, C.f.D.E.a.R.(CDER) (Eds.), Federal Register, Rockville, MD: 70 (2005) pp. 42346. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Seidman AD, One-hour paclitaxel via weekly infusion: dose-density with enhanced therapeutic index, Oncology (Williston Park) 12 (1998) 19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Xiao H, Song H, Yang Q, Cai H, Qi R, Yan L, et al. , A prodrug strategy to deliver cisplatin(IV) and paclitaxel in nanomicelles to improve efficacy and tolerance, Biomaterials 33 (2012) 6507–6519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Song W, Tang Z, Li M, Lv S, Sun H, Deng M, et al. , Polypeptide-based combination of paclitaxel and cisplatin for enhanced chemotherapy efficacy and reduced side-effects, Acta Biomater. 10 (2014) 1392–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].He Z, Huang J, Xu Y, Zhang X, Teng Y, Huang C, et al. , Co-delivery of cisplatin and paclitaxel by folic acid conjugated amphiphilic PEG-PLGA copolymer nanoparticles for the treatment of non-small lung cancer, Oncotarget. 6 (2015) 42150–42168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Fang Y, Zheng G, Yang J, Tang H, Zhang Y, Kong B, et al. , Dual-pore mesoporous carbon@silica composite core-shell nanospheres for multidrug delivery, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 53 (2014) 5366–5370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Shen W, Chen X, Luan J, Wang D, Yu L, Ding J, Sustained Codelivery of Cisplatin and Paclitaxel via an Injectable Prodrug Hydrogel for Ovarian Cancer Treatment, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9 (2017) 40031–40046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sethi M, Sukumar R, Karve S, Werner ME, Wang EC, Moore DT, et al. , Effect of drug release kinetics on nanoparticle therapeutic efficacy and toxicity, Nanoscale 6 (2014) 2321–2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kabanov AV, Alakhov VY, Pluronic block copolymers in drug delivery: from micellar nanocontainers to biological response modifiers, Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier Syst. 19 (2002) 1–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Batrakova EV, Li S, Li Y, Alakhov VY, Elmquist WF, Kabanov AV, Distribution kinetics of a micelle-forming block copolymer Pluronic P85, J. Control. Release 100 (2004) 389–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Paal K, Muller J, Hegedus L, High affinity binding of paclitaxel to human serum albumin, Eur. J. Biochem 268 (2001) 2187–2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Miele E, Spinelli GP, Miele E, Tomao F, Tomao S, Albumin-bound formulation of paclitaxel (Abraxane ABI-007) in the treatment of breast cancer, Int. J. Nanomedicine 4 (2009) 99–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Cabral H, Matsumoto Y, Mizuno K, Chen Q, Murakami M, Kimura M, et al. , Accumulation of sub-100 nm polymeric micelles in poorly permeable tumours depends on size, Nat. Nanotechnol 6 (2011) 815–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Yokoi K, Chan D, Kojic M, Milosevic M, Engler D, Matsunami R, et al. , Liposomal doxorubicin extravasation controlled by phenotype-specific transport properties of tumor microenvironment and vascular barrier, J. Control. Release 217 (2015) 293–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Yokoi K, Kojic M, Milosevic M, Tanei T, Ferrari M, Ziemys A, Capillary-wall collagen as a biophysical marker of nanotherapeutic permeability into the tumor microenvironment, Cancer Res. 74 (2014) 4239–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.