Abstract

Potassium ion (K+) homeostasis and dynamics play critical roles in biological activities. Here we describe three genetically encoded K+ indicators. KIRIN1 (potassium (K) ion ratiometric indicator) and KIRIN1-GR are Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based indicators with a bacterial K+ binding protein (Kbp) inserting between the fluorescent protein FRET pairs mCerulean3/cp173Venus and Clover/mRuby2, respectively. GINKO1 (green indicator of K+ for optical imaging) is a single fluorescent protein-based K+ indicator constructed by insertion of Kbp into enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP). These indicators are suitable for detecting K+ at physiologically relevant concentrations in vitro and in cells. KIRIN1 enabled imaging of cytosolic K+ depletion in live cells and K+ efflux and reuptake in cultured neurons. GINKO1, in conjunction with red fluorescent Ca2+ indicator, enable dual-color imaging of K+ and Ca2+ dynamics in neurons and glial cells. These results demonstrate that KIRIN1 and GINKO1 are useful tools for imaging intracellular K+ dynamics.

Yi Shen et al. report two classes of genetically encoded fluorescent potassium indicators, based on FRET (KIRIN1 and KIRIN1-GR) or single-wavelength fluorescence change (GINKO1). These K+ indicators enable imaging of intracellular K+ dynamics in live cells with a multiplexing potential.

Introduction

Intracellular and extracellular potassium ion (K+) concentration affects all aspects of cellular homeostasis1. Normal levels of K+ concentration (~150 mM for intracellular K+; ~5 mM for extracellular K+) are vital for the proper functioning of neuronal2,3, cardiovascular4, and immune systems5–7. Abnormal K+ concentration levels are often associated with disease conditions8,9. Measuring K+ concentration has predominantly relied on K+-specific glass capillary electrodes10. Although sensitive and accurate, such electrode-based measurements are invasive, time consuming, and low throughput. Electrode-based measurements also provide little to no spatiotemporal information on K+ dynamics in biological samples. Alternatively, synthetic small molecule-based K+-sensitive fluorescent dyes have been developed, but these dyes usually have poor selectivity and bind to Na+ with similar affinity11,12. K+-sensitive dyes with improved selectivity have been recently reported13,14, but the use of synthetic dyes still involves cumbersome loading and washing steps. In addition, it is generally impractical to target synthetic dyes to specific cells within a tissue.

Much as genetically encoded calcium ion (Ca2+) indicators have revolutionized the study of cell signaling and Ca2+ biology in vivo, so might genetically encoded K+ indicators revolutionize the study of K+ homeostasis and dynamics in live cells and in vivo. Genetically encoded K+ indicators would allow accurate measurement of K+ concentration in specific cell types or cellular organelles with high spatial and temporal resolution. The key to designing such indicators is to identify or develop a suitable sensing domain with a high degree of specificity toward K+ as well as sufficient levels of conformational change upon binding to K+. Recently, an Escherichia coli K+ binding protein (Kbp) was identified and structurally characterized15. Kbp is a small (149 residues, 16 kDa) cytoplasmic protein that binds K+ with high specificity. It contains two domains: BON (bacterial OsmY and nodulation)16 at the N terminus and LysM (lysin motif)17 at the C terminus. Small-angle X-ray scattering structural analysis of Kbp revealed that the protein exhibits a global conformational change upon K+-dependent association of the BON and LysM domains15. Such a conformational change is an important prerequisite for developing an effective genetically encoded K+ indicator.

Genetically encoded indicators have been widely used for studying various biochemical activities in live cells18,19. Among these indicators, intramolecular Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based indicators are particularly useful for detecting binding-induced protein conformational changes20. The design principle of such indicators is straightforward and well established: a sensing domain is attached to two fluorescent proteins as a single polypeptide chain. Upon analyte binding, the conformational change of the sensing domain affects the FRET efficiency between the attached fluorophores, thus altering the ratiometric fluorescence emission21. FRET ratio is independent of protein expression levels, and therefore it can be utilized for quantitative imaging in live cells. A drawback of FRET-based indicators is that they each span a large portion of the visible spectrum due to the employment of two fluorescent proteins, limiting their applications in multiplexed imaging experiments. Single fluorescent protein-based indicators typically utilize the conformational change of the sensing domain to allosterically alter the fluorescent protein chromophore environment, resulting in an intensiometric change in fluorescence22. Due to their narrower spectral profiles, single fluorescent protein-based indicators are more suitable for multiparameter imaging23.

The development of fluorescent protein-based genetically encoded indicators for Ca2+, Zn2+, Mg2+, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), neurotransmitters, membrane voltage, and various enzyme activities has led to numerous new biological insights24–32. However, analogous indicators for monovalent metal cations have been absent from this toolkit until the recent report of FRET-based potassium (K+) indicators, known as GEPIIs (genetically encoded potassium ion indicators), based on Kbp and the mseCFP/cpVenus FRET pair32,33. GEPIIs were successfully used to quantify K+ in biological samples in vitro and to visualize K+ concentrations in cells33.

Here we report an independent and parallel effort to engineer and characterize genetically encoded K+ indicators based on Kbp. We describe both a cyan-yellow potassium (K) ion ratiometric indicator (KIRIN1) and green-red (KIRIN1-GR) FRET-based K+ indicators, as well as a single fluorescent protein-based green indicator of K+ for optical imaging (GINKO1). Considering their independent origins, KIRIN1 and GEPII are remarkably similar in terms of design and performance, although different donor fluorescent proteins were utilized in KIRIN1 and the GEPIIs. KIRIN1-GR is a spectrally distinct FRET-based indicator, while GINKO1 is single fluorescent protein-based K+ indicator. These indicators enable imaging of intracellular K+ concentrations in live mammalian cell lines and dissociated neurons as proof-of-principle demonstrations.

Results

Development of FRET-based K+ indicators

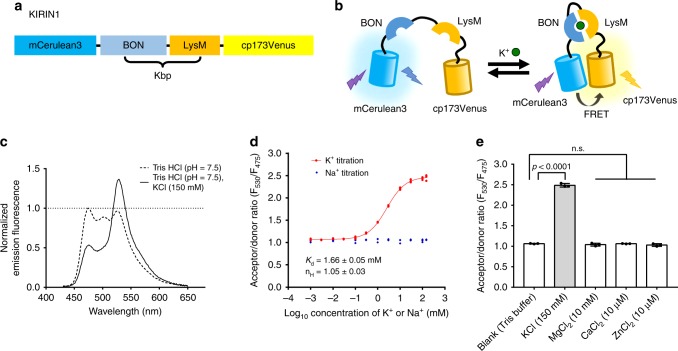

We designed genetically encoded K+ indicators based on the fusion of a fluorescent protein donor–acceptor FRET pair to the termini of Kbp (Fig. 1a). Apo-Kbp adopts an elongated conformation with N/C termini relatively far away from each other; the K+-bound Kbp showed a globular conformation with its N/C termini close to each other15. Upon K+ binding, the conformational change of Kbp brings the fused fluorescent protein donor and acceptor closer together, thus increasing the FRET efficiency and resulting in a ratiometric fluorescence change (donor emission fluorescence decrease and acceptor emission fluorescence increase) (Fig. 1b). We constructed a fusion protein consisting of the cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) mCerulean3 as the FRET donor34 and a variant of yellow fluorescent protein (YFP), cp173Venus35, as the FRET acceptor. The donor, mCerulean3, is the brightest CFP currently available36 with a high quantum yield at 0.80. The acceptor, cp173Venus, is a bright FRET acceptor that has been optimized for high FRET efficiency with a CFP-based donor35. mCerulean3 is linked to the N terminus of Kbp (residues 2–149) and cp173Venus is attached to the C terminus (Fig. 1a, b). The resulting construct was designated KIRIN1.

Fig. 1.

Design and in vitro characterization of KIRIN1. a Design and construction of the genetically encoded K+ indicator KIRIN1. mCerulean3 (residues 1–228) at the N terminus is linked with Kbp (residues 2–149), followed by cp173Venus (full length) at the C terminus. b Schematic representation of the molecular sensing mechanism of KIRIN1. Binding of K+ induces a structural change in the Kbp protein, increasing the FRET efficiency between mCerulean3 and cp173Venus in KIRIN1. c KIRIN1 emission fluorescence spectrum (excitation 410 nm, emission 430 nm to 650 nm) in Tris HCl buffer with (solid) and without (dashed) K+. d FRET acceptor-to-donor fluorescence ratio (F530/F475) of purified KIRIN1 protein at various concentrations (1 µM to 150 mM) of K+ (red) and Na+ (blue) solutions, data are expressed as individual data points. e FRET acceptor-to-donor fluorescence ratio of purified KIRIN1 protein upon addition of various physiologically relevant ions including Mg2+ (10 mM), Ca2+ (10 µM), and Zn2+ (10 µM), data are expressed as mean ± SD

To investigate the potential utility of KIRIN1 as a K+ indicator, the protein was purified and characterized in vitro. To determine the K+-induced FRET efficiency change, we first measured the emission spectrum (430 nm to 650 nm) of KIRIN1 protein in Tris buffer (Fig. 1c). Upon adding 150 mM K+, the mCerulean3 emission (~475 nm) decreased by ~50% and cp173Venus (~530 nm) emission increased by ~30%, indicating an increase in FRET efficiency. The maximum FRET acceptor and donor fluorescence emission intensity ratio (R = F530/F475) change (ΔR/Rmin) was 130%, which is a relatively large change compared to other first-generation CFP-YFP-based FRET sensors. However, it is not as large as changes for highly optimized FRET-based indicators35,37.

To determine the K+ affinity of KIRIN1, we measured the mCerulean3 and cp173Venus fluorescence emission ratio (F530/F475) in the presence of K+ concentrations ranging from 1 µM to 150 mM (Fig. 1d). The indicator showed FRET ratio changes over concentrations ranging from 0.1 mM to 100 mM K+. The K+ titration curve was fitted with a one-site saturation model, yielding an apparent dissociation constant (Kd) of 1.66 ± 0.05 mM and an apparent Hill coefficient (nH) of 1.05 ± 0.03 (Fig. 1d). To test the selectivity for K+ relative to Na+, we incubated KIRIN1 with Na+ at concentrations from 1 µM to 150 mM. The emission ratio remained unchanged upon the addition of Na+ even at 150 mM (Fig. 1d), indicating that KIRIN1 has a high degree of selectivity for K+ over Na+. Furthermore, KIRIN1 exhibited no significant FRET ratio change upon the addition of physiologically relevant concentrations of other ions including Mg2+ (10 mM), Ca2+ (10 µM), and Zn2+ (10 µM) (Fig. 1e), further demonstrating the specificity of KIRIN1 for K+. We also carried out kinetic characterization using stopped-flow fluorescence, which revealed a kon of 28.5 ± 0.8 mM−1 s−1 and a koff of 105.5 ± 5.3 s−1 for K+ binding to KIRIN1. These results indicate that KIRIN1 has a rapid kinetic response to changes in K+ concentration (Supplementary Fig. 1a).

To compare KIRIN1 with previously published GEPII, we measured the FRET spectral change, K+ affinity, and ion specificity of GEPII1.0 in parallel with KIRIN1. GEPII1.0 showed a maximum ΔR/Rmin of 220%, which is higher than 130% of KIRIN1. The apparent Kd for binding K+ is similar with GEPII1.0 exhibiting a Kd of 2.63 ± 0.02 mM and KIRIN1 exhibiting a Kd of 1.66 ± 0.05 mM. Both indicators had highly similar selectivity toward K+ over other physiologically relevant ions as expected (Supplementary Fig. 2).

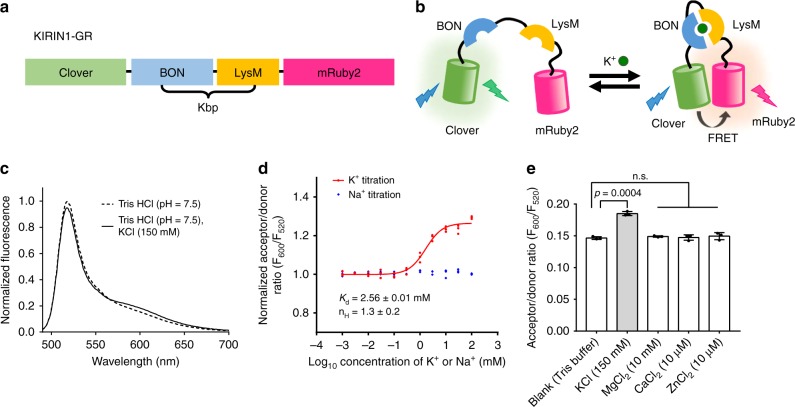

In a parallel effort, we constructed a red-shifted FRET-based K+ indicator using the Clover green fluorescent protein (GFP) and the mRuby2 red fluorescent protein (RFP) pair38 (Fig. 2a, b). The resulting indicator, KIRIN1-GR (KIRIN1 with GFP and RFP), exhibited a Kd of 2.56 ± 0.01 mM for K+. Like KIRIN1, it was selective for K+, though the in vitro K+–induced ΔR/Rmin was just 20% (Fig. 2c–e).

Fig. 2.

Design and in vitro characterization of KIRIN1-GR. a Design and construction of the genetically encoded K+ indicator KIRIN1-GR. b Schematic of the molecular sensing mechanism of KIRIN1-GR. c Emission fluorescence spectrum of KIRIN1-GR with (solid) and without (dashed) K+. d K+ titration curve (red) and Na+ titration (blue) of KIRIN1-GR according to FRET acceptor-to-donor fluorescence ratio (F600/F520), data are expressed as individual data points. e FRET acceptor-to-donor fluorescence ratio of the genetically encoded K+ indicator elicited by adding different physiologically relevant ions including Mg2+ (10 mM), Ca2+ (10 µM), and Zn2+ (10 µM), data are expressed as mean ± SD

Development of a single fluorescent protein-based K+ indicator

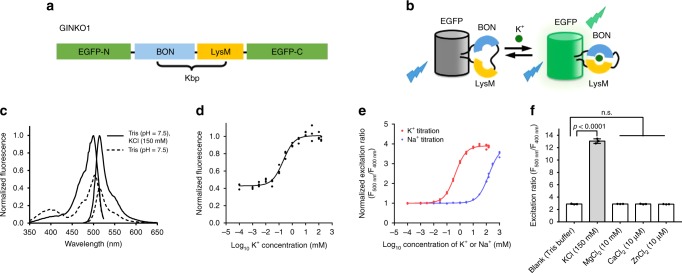

We next sought to engineer a single fluorescent protein-based K+ indicator. We first attempted to engineer such an indicator based on a circularly permutated (cp) enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) scaffold similar to the design of GCaMP39 series of Ca2+ indicators. In this design, the BON and LysM domains of Kbp were split and fused to the N and C termini, respectively, of cpEGFP. The resulting protein exhibited green fluorescence, but this fluorescence did not change upon addition of K+, possibly because the K+-binding function of Kbp was abolished by the genetic splitting of the two domains. We next explored an alternate indicator topology by inserting an intact Kbp into a fluorescent protein. This approach has been previously used for Ca2+ and glutamate indicators40–42. We found that insertion of Kbp into the EGFP scaffold of GCaMP6s at residue 144 yielded a functional green fluorescent indicator for K+ (Fig. 3a, b). This indicator was designated as GINKO1.

Fig. 3.

Design and in vitro characterization of GINKO1. a Design and construction of the genetically encoded K+ indicator GINKO1. b Schematic representation of the molecular sensing mechanism. c GINKO1 excitation and emission fluorescence spectrum in buffer with (solid) and without (dashed) K+. d Normalized emission intensity of purified GINKO1 protein at various concentrations of K+, data are expressed as individual data points. e Excitation ratio of purified GINKO1 protein at various concentrations of K+ (red) and Na+ (blue) solutions, data are expressed as individual data points. f Excitation fluorescence ratio of purified GINKO1 protein upon addition of various physiologically relevant ions, data are expressed as mean ± SD

To characterize GINKO1, we first measured the fluorescence excitation and emission spectrum of purified indicator in Tris buffer with and without K+ (Fig. 3c). The excitation and emission maxima of apo-GINKO1 are 502 and 514 nm, respectively. In the K+-bound state, the excitation maximum is slightly blue-shifted to 500 nm, most likely due to an alteration of chromophore environment. Upon the addition of 150 mM K+, the green fluorescence emission (514 nm) intensity increased to ~250% of its initial intensity (Fig. 3c, d). This increased intensity is attributed to an increase in extinction coefficient from 17,600 M−1 cm−1 to 37,300 M−1 cm−1. The quantum yield remained essentially unchanged (0.20 in the absence of K+ and 0.21 in the presence of K+). GINKO1 also exhibited a K+-dependent 3.5-fold change in excitation ratio, making it both an intensiometric and excitation ratiometric indicator (Fig. 3d, e). To determine the K+ affinity of GINKO1, we measured the green fluorescence excitation ratio (F500/F400) over K+ concentrations ranging from 1 µM to 150 mM (Fig. 3e). The K+ titration curve revealed an apparent Kd of 0.42 ± 0.03 mM and an apparent Hill coefficient (nH) of 1.05 ± 0.03 (Fig. 3e). To test the selectivity for K+ relative to Na+, we titrated Na+ over the concentration range from 1 µM to 1 M (higher concentrations of Na+ lead to sensor protein precipitation). GINKO1 fluorescence excitation ratio (F500/F400) exhibited an ~3-fold change upon addition of 1 M Na+ (Fig. 3e). Fitting of the Na+ titration curve revealed an apparent Kd of 153 ± 8 mM and an apparent nH of 1.04 ± 0.05 (Fig. 3e). The apparent Kd for Na+ is over 350 times higher than that for K+, indicating that GINKO1 is highly selective towards K+ over Na+. It is possible that the insertion of Kbp into cpEGFP resulted in a structural change in the ion binding site of Kbp, leading to increased affinity for both K+ and Na+. GINKO1 exhibited no significant excitation ratio change upon the addition of other ions including Mg2+ (10 mM), Ca2+ (10 µM), or Zn2+ (10 µM) (Fig. 3f), confirming its K+ specificity. Stopped-flow kinetic characterization of GINKO1 revealed kon = 9.32 ± 0.25 mM−1 s−1 and koff = 85.9 ± 1.6 s−1 for K+ binding, similar to the kinetic constants for KIRIN1 (Supplementary Fig. 1b).

Imaging intracellular K+ in HeLa cells

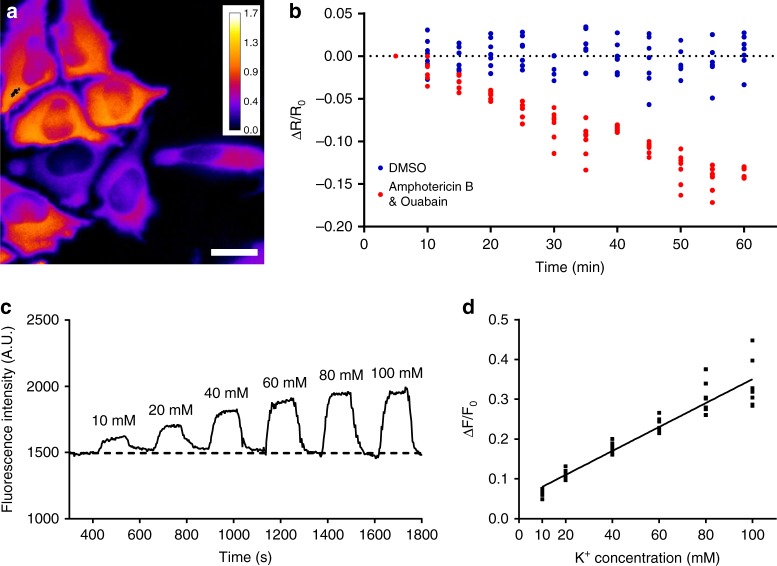

The in vitro characterization suggested that Kbp-based genetically encoded K+ indicators could be utilized for visualizing intracellular K+ dynamics in live cells. To test the performance of KIRIN1, HeLa cells (an immortalized human cervical cancer cell line) were transfected with the plasmid encoding KIRIN1. Changes in intracellular K+ concentrations were then induced pharmacologically using amphotericin B, an antifungal drug that induces K+ efflux, and ouabain, an inhibitor of sodium-potassium ion pump (Na/K-ATPase). Addition of both amphotericin B and ouabain to HeLa cells has been reported to deplete intracellular K+ content43,44. Cells were imaged in both the CFP (excitation 436/20 nm emission 483/32 nm) and FRET (excitation 438/24 nm, emission 544/24 nm) channels, and the FRET ratio image of KIRIN1 was calculated by dividing the FRET channel image by the CFP channel image (Fig. 4a). Upon treatment with 5 µM amphotericin B and 10 µM ouabain, the indicator exhibited a gradual decrease of 15% in FRET ratio over a period of ~60 min, signaling a decrease of K+ concentrations in cells (Fig. 4b). The control experiment using KIRIN1-expressing cells treated with dimethyl sulfoxide vehicle revealed no significant change in FRET ratio over the same time period (Fig. 4b). Under similar testing conditions KIRIN1-GR gave an 8% decrease in FRET ratio upon amphotericin B and ouabain treatment (Supplementary Fig. 3). These findings demonstrate that KIRIN1 and KIRIN1-GR are capable of monitoring intracellular K+ changes across a population of live cells in real time.

Fig. 4.

Imaging intracellular K+ in HeLa cells. a Representative FRET acceptor (excitation 438/24 nm, emission 544/24 nm) to donor (excitation 436/20 nm emission 483/32 nm) fluorescence ratio (R = Facceptor/Fdonor) image of live HeLa cells expressing KIRIN1 (scale bar = 20 µm). b Trace (red) of FRET acceptor-to-donor fluorescence ratio change (ΔR/R0) after treatment of live HeLa cells expressing KIRIN1 with 5 µM amphotericin B and 10 µM ouabain (n = 7), trace (blue) of FRET acceptor-to-donor fluorescence percentage ratio change (ΔR/R0) without chemical treatment (n = 13) on live HeLa cells expressing KIRIN1, data are expressed as individual data points. c Representative trace for a HeLa cell permeabilized using valinomycin for K+ and perfused with a series buffer with different K+ concentrations for in situ calibration of GINKO1. d Fluorescence intensity changes (ΔF/F0) (n = 7) plotted against corresponding known K+ concentrations, data are expressed as individual data points

To characterize the capability of GINKO1 for measuring intracellular K+, we expressed the gene in HeLa cells via transient transfection. Cells were permeabilized with K+-specific ionophore valinomycin, which enables the K+ concentrations in cells to be externally manipulated. Solutions of different K+ concentrations (10 to 100 mM) were perfused sequentially. In between each perfusion, cells were washed with culture medium containing 3 mM K+. The GINKO1 fluorescence intensity was recorded (Fig. 4c) and the fluorescence intensity changes (ΔF/F0) were plotted against the extracellular K+ concentrations (Fig. 4d). GINKO1 fluorescence intensity increased in proportion to K+ concentrations over the range of 3 mM to 100 mM. This result demonstrates the potential of using GINKO1 to detect and potentially quantify a wide range of K+ concentrations in cells.

Imaging intracellular K+ dynamics in neurons with KIRIN1

K+ plays an essential role in maintaining the normal neuronal physiology. Previous studies45–50, using electrode-based measurements of extracellular K+ concentration, have revealed that overactivation of glutamate receptors using glutamate mediates a strong K+ efflux from neurons. The K+ efflux is followed by slower influx to restore membrane potential after glutamate is removed. We examined whether these changes in intracellular K+ can be detected optically using KIRIN1. We utilized cultured primary cortical neurons isolated from rat and expressed KIRIN1 using transient transfection. KIRIN1 fluorescence was distributed evenly throughout the cytosol (Fig. 5a–c). After perfusion of glutamate for a short period (30 s), neurons expressing KIRIN1 underwent a 15% decrease in FRET ratio within 200 s. Following washing out of glutamate, the FRET ratio of KIRIN1 returned close to the baseline in ~400 s (Fig. 5d, e), suggesting a slow re-equilibration of intracellular K+ concentration in neurons. The observed FRET change is consistent with previous measurements using both electrodes48 and a synthetic fluorescent K+ indicator dye12.

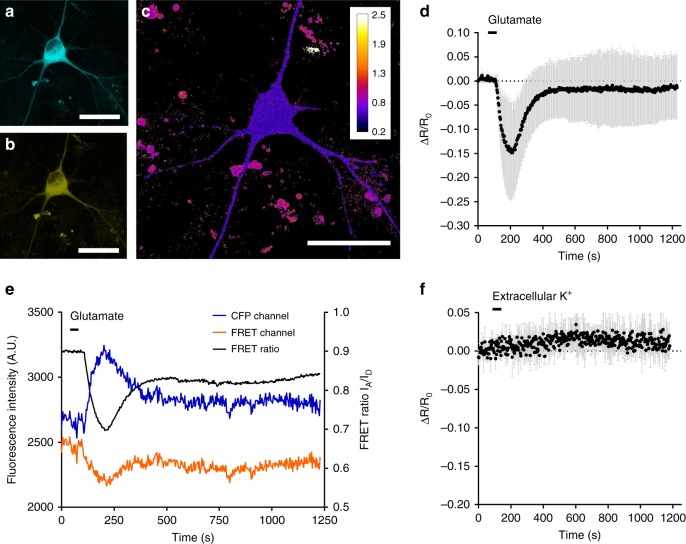

Fig. 5.

Imaging neuronal K+ dynamics using KIRIN1. a Representative donor channel image of dissociated cortical neuron expressing KIRIN1 (scale bar = 30 µm). b Representative FRET channel image (scale bar = 30 µm). c Representative FRET ratio image (scale bar = 30 µm). d FRET acceptor-to-donor fluorescence percentage ratio change time course with the treatment of glutamate (500 µM, n = 3), data are expressed as mean ± SD. e Representative traces of CFP channel intensity (blue), FRET channel intensity (orange), and FRET acceptor-to-donor fluorescence ratio (black) with the treatment of glutamate (500 µM). f FRET acceptor-to-donor fluorescence percentage ratio change time course with treatment with a high concentration (30 mM) of extracellular K+ (n = 3), data are expressed as mean ± SD

To further confirm that the FRET ratio change was due to K+ concentration changes, rather than other cellular changes associated with neuronal activities, we performed the same set of experiments but replaced glutamate stimulation with a high extracellular concentration of K+ (30 mM)51. This condition depolarizes neurons but does not cause a major K+ efflux, possibly due to the fact that the K+ gradient across the membrane is reduced and thus the driving force for outward K+ current is attenuated46–50. Under these conditions, neurons expressing KIRIN1 did not undergo any detectable decrease in FRET ratio (Fig. 5f), confirming that KIRIN1 FRET changes specifically reflect K+ dynamics during neuronal activity.

Concurrent imaging of K+ and Ca2+ dynamics in neurons

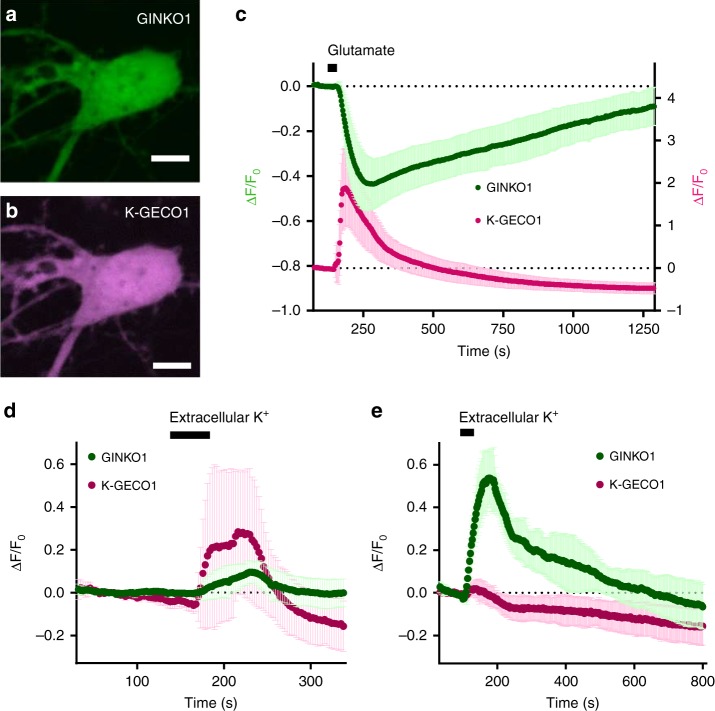

One of the advantages of single fluorescent protein-based indicators is that, relative to FRET-based indicators, they can be readily combined with other fluorescent proteins for multiparameter imaging. To explore whether GINKO1 could be used with a red fluorescent Ca2+ indicator for imaging of K+ and Ca2+ dynamics in the same cell, we co-expressed GINKO1 and K-GECO1 (ref. 52) in cultured cortical neurons (Fig. 6a, b). Neuronal activity was evoked by a short exposure (30 s) to glutamate (500 µM). Following this treatment, the red fluorescence from K-GECO1 rapidly increased by an average of 188% within 10 s, followed by a gradual decrease back to baseline in 300 s (n = 10) (Fig. 6c, magenta trace). The green fluorescence of GINKO1 underwent a relatively slow, but substantial, decrease of 43% in 120 s, and then recovered back to baseline level after 900 s (n = 10) (Fig. 6c, green trace), consistent with the results from KIRIN1 in neurons with glutamate stimulation.

Fig. 6.

Dual-Color imaging of K+ and Ca2+ dynamics in cultured cortical dissociated neurons and glial cells. a Representative GFP channel fluorescence image of neuron soma region expressing GINKO1 (scale bar = 5 µm). b Representative RFP channel fluorescence image of neuron soma region expressing K-GECO1 (scale bar = 5 µm). c Normalized fluorescence intensity change (ΔF/F0) time course of GINKO1 and K-GECO1 with stimulation (30 s, 500 µM) of glutamate on neurons (n = 10), data are expressed as mean ± SD. d Normalized fluorescence intensity change (ΔF/F0) time course of GINKO1 and K-GECO1 with stimulation by a high concentration (30 mM) of extracellular K+ on neurons (n = 7), data are expressed as mean ± SD. e Normalized fluorescence intensity change (ΔF/F0) time course of GINKO1 and K-GECO1 with stimulation by a high concentration (30 mM) of extracellular K+ on glial cells (n = 4), data are expressed as mean ± SD

We further imaged neuronal K+ and Ca2+ changes with stimulation using high extracellular concentrations of K+ (30 mM). Cultured dissociated cortical neurons were perfused for 60 s with 30 mM extracellular K+. Following the stimulation, a 28% increase in K-GECO1 red fluorescence was observed due to neuronal depolarization and Ca2+ influx (n = 7) (Fig. 6d, magenta trace). In the same cells, GINKO1 green fluorescence exhibited a 9% increase (Fig. 6d, green trace), indicating a K+ influx. This K+ influx was not detected by KIRIN1 under the same experimental conditions, suggesting that GINKO1 is a more sensitive indicator for reporting intracellular K+ concentration elevation.

Building upon this insight, we continued to explore the K+ and Ca2+ dynamics in (astrocytic) glial cells using GINKO1 and K-GECO1. Compared to neurons, glial cells have relatively hyperpolarized resting membrane potentials and high K+ permeability53,54. These electrophysiological properties of glial cells contribute to their function in maintaining and regulating extracellular K+ concentration. Accordingly, an elevated extracellular K+ concentration should trigger K+ uptake by glial cells, leading to an increase in intracellular K+ concentration49,50,55,56. Glial cells expressing both GINKO1 and K-GECO1 were stimulated using 30 mM extracellular K+ for 60 s. Upon treatment, GINKO1 green fluorescence intensity increased by 53% (n = 4) (Fig. 6e, green trace), a more substantial increase than the 9% increase observed for identically treated neurons. K-GECO1 red fluorescence showed a slight increase of 4% (n = 4) (Fig. 6e, magenta trace). These results support the notion that glial cells regulate extracellular K+ homeostasis57, and also reveal the differential response of glial cells versus neurons in handling K+ and Ca2+ under depolarized conditions.

Discussion

We have developed a genetically encoded FRET-based K+ indicator, KIRIN1, based on bacterial Kbp and the FRET pair of mCerulean3 and cp173Venus. Characterization of KIRIN1 revealed that the FRET efficiency changes over the physiologically relevant range of K+ concentrations. The dynamic range (based on FRET emission ratio) of KIRIN1 in vitro is 130%, which is comparable to some optimized FRET-based indicators58,59. Importantly, KIRIN1 is much more selective for K+ than Na+, due to the inherent K+ selectivity of Kbp15. Our findings on KIRIN1 are largely consistent with the similarly designed K+ indicator, GEPII1.0, which also uses Kbp and a cyan/yellow FRET pair33. The main difference between GEPII1.0 and KIRIN1 is the use of mseCFP versus mCerulean3, respectively, as FRET donors. Both indicators use Kbp as a sensing domain and cp173Venus as a FRET acceptor. In addition to KIRIN1, we constructed another K+ indicator, KIRIN1-GR, based on the green and red fluorescent protein FRET pair Clover/mRuby2. However, the change in FRET ratio of KIRIN1-GR is substantially smaller than that of KIRIN1. The decreased FRET ratio change may be due to the relatively low quantum yield of the mRuby2 (0.38) FRET acceptor60 and the absence of a weak dimerization effect, which is present in the CFP/YFP pair61,62. Nonetheless, due to its red-shifted spectrum and large difference in fluorescence hue between donor and acceptor, the GFP/RFP FRET-based KIRIN1-GR may offer a high signal-to-background ratio with minimal spectral bleed-through60. Future efforts to increase the KIRIN1-GR FRET change could be directed at replacing the Clover/mRuby2 FRET pair with brighter GFPs such as mClover3 or mNeonGreen, and brighter RFPs such as mRuby3 or mScarlet38,63,64. These findings provide further support for the conclusion of Bischof et al.33, who found that Kbp-based FRET K+ indicators are well suited for sensing K+ in vitro and in live cells.

We have also developed a single fluorescent protein-based green fluorescent K+ indicator, GINKO1, which was constructed by inserting the Kbp domain into an EGFP scaffold. K+ binding induces conformational changes of Kbp and modulation of the fluorescent protein fluorescence, which is most likely associated with alteration of the equilibrium between the protonated and deprotonated forms of the EGFP chromophore65. This design enables the detection of K+ dynamics based on single emission wavelength fluorescence intensity changes. In vitro characterization of GINKO1 revealed that it has 2.5-fold fluorescent intensity change (Fmax/Fmin) upon K+ binding. Titration revealed that GINKO1 also responds to very high concentrations of Na+. Single fluorescent protein-based indicators offer several advantages relative to their FRET-based counterparts. Specifically, they can be more easily used for simultaneous multiparameter imaging with minimal spectral bleed-through. In addition, single fluorescent protein-based indicators have the potential to be engineered for larger intensity-based fluorescence changes, as demonstrated by the highly effective optimization of the GCaMP series of Ca2+ indicators66. Beyond the typical advantages of single fluorescent protein-based indicators, GINKO1 is also excitation ratiometric. With an approximately 4-fold K+ binding-induced excitation ratio change (Rmax/Rmin), GINKO1 is suitable for ratiometric imaging. Ratiometric imaging is preferable for quantitative imaging as it enables experimental correction for intensity differences that are due to variability in protein expression levels. Coupling GINKO1 with an ion-insensitive fluorescent marker (in a distinct spectral channel) could also correct for such imaging artifacts. For these reasons, we anticipate that further optimized versions of GINKO1 will ultimately be the most versatile tools for K+ imaging, and likely far surpass the performance of the FRET-based counterparts, KIRIN1 and GEPIIs.

Single fluorescent protein-based GINKO1, FRET-based KIRIN1, and the previously reported FRET-based GEPIIs33 are indicators with large dynamic range and high specificity, making them promising probes for K+ imaging. Our imaging experiments in cell lines and dissociated neurons have demonstrated that both KIRIN1 and GINKO1 are useful for imaging K+ dynamics intracellularly. The advent of Kbp-based K+ biosensors will open new avenues for investigation of cellular signaling associated with normal or abnormal K+ dynamics at the single-cell level or across large cell populations. As they are genetically encoded, these indicators are compatible with in vivo expression in animal models, either with viral vectors or through transgenic technology. Potential future applications include imaging K+ spatial buffering in glial cells56, studying extracellular K+ dynamics during cortical spreading depression67 and sleep/wake cycle68, and imaging K+ efflux during macrophage innate immunity NLRP3 activation69. Application of K+ indicators to these problems, and others, will ultimately provide a deeper understanding of the role of K+ dynamics in vivo.

Methods

Plasmid DNA construction

DNA encoding KIRIN1 was synthesized and cloned into the pET28a expression vector by GenScripts. For KIRIN1-GR, the Kbp sequence was synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) as a double-stranded DNA fragment; DNA encoding Clover and mRuby2 was obtained from Addgene (plasmid #49089). For GINKO1, the DNA sequence was synthesized by IDT as a double-stranded DNA fragment. For GEPII1.0, plasmid was purchased from NGFI Next Generation Fluorescence Imaging GmbH. DNA fragments of GINKO1 and GEPII1.0 were PCR amplified using Phusion polymerase and then cloned into the pBAD/His-B expression vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using Gibson assembly (New England Biolabs). KIRIN1, KIRIN1-GR, and GINKO1 genes were PCR amplified, digested, and ligated into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). pcDNA3.1-NES-KIRIN1 was constructed by PCR with the primer containing the nuclear exclusion signal (NES) encoding the sequence (LALKLAGLDIGS). All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

In vitro characterization

The indicator proteins were expressed as His-tagged recombinant proteins in E. coli, with an induction temperature of 30 °C overnight. Bacteria were harvested at 10,000 rpm, 4 °C for 10 min. Cell pallet was lysed using sonication, and then clarified using centrifuge at 14,000 rpm for 30 min. The protein was purified from the supernatant by affinity chromatography using Ni-NTA agarose resin (McLab). Eluted protein solution was then buffer exchanged using a PD-10 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) desalting column. For K+ Kd determination, purified protein was diluted into a series of buffers with K+ concentration ranging from 0 to 150 mM. The fluorescence spectrum of the KIRIN1 in each solution (100 µL) was measured using a Tecan Safire2 microplate reader with excitation at 410 nm and emission from 430 nm to 650 nm. The fluorescence spectrum of the KIRIN1-GR in each solution (100 µL) was measured using a Biotek microplate reader with excitation at 470 nm and emission from 490 nm to 700 nm. The fluorescence spectrum of the GINKO1 in each solution (100 µL) was measured using a Tecan Safire2 microplate reader. Titration experiments were performed in triplicate. The FRET ratios for KIRIN1 and KIRIN1-GR or excitation ratios for GINKO1 were plotted as a function of K+ concentrations. Graphpad Prism software was used to fit the data and obtain apparent Kd and the apparent Hill coefficient for K+ binding. The brightness of GINKO1 was measured in the presence and absence of K+. The purified GINKO1 protein was subject to buffer exchange to either K+ and Na+ free 50 mM Tris buffer or 150 mM KCl, 50 mM Tris buffer with PD-10 columns (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The concentration of GINKO1 was determined with base denaturation36 and the absorbance was measured with Backman Coulter DU 800 spectrophotometer to determine the extinction coefficient. The quantum yield was measured with EGFP as the control and the fluorescence was measured with a Tecan Safire2 microplate reader. Data were processed with Microsoft Excel. Stopped-flow kinetic measurements were performed on a SX20 Stopped-Flow Reaction Analyzer (Applied Photophysics). For KIRIN1, the excitation wavelength was 430 nm with 2 nm bandwidth and collected emitted light at 530 nm through a 10 mm path. For GINKO1, the excitation wavelength was 488 nm with 2 nm bandwidth and collected emitted light at 520 nm through a 10 mm path. A total of 200 data points were collected over 5 replicates throughout the reaction and the fluorescence changes were examined for 250 ms. Reactions were initiated by mixing equal volumes of diluted purified protein in Tris buffer (100 mM, pH = 7.50) and varying concentrations of KCl (2, 10, and 20 mM) at 20 °C. Data were analyzed with Graphpad Prism to obtain the observed rate constant Kobs and determine rate constants of association kon and dissociation koff.

Live cell imaging

For K+ imaging of mammalian cell line, HeLa cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Thermo Fisher Scientific), penicillin–streptomycin antibiotics (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and GlutaMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Hela cells with 60–70% confluence on 35 mm glass-bottom dishes (In Vitro Scientific) were transfected using Polyjet (SignaGen), Turbofect (Thermo Fisher Scientific), or Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were imaged 18–24 h after transfection. Medium was replaced with 1 mL of 20 mM HEPES buffered Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS; HHBSS) immediately before imaging. Imaging was performed with a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope with a 40× objective. HeLa cell images were acquired with Molecular Devices MetaMorph and processed using ImageJ.

For K+ imaging of cultured dissociated neurons and (likely astrocytic) glial cells, dissociated E18 Sprague Dawley cortical neurons were grown on 35 mm glass-bottom dishes containing NbActiv4 medium (BrainBits LLC) with 2% FBS and penicillin–streptomycin antibiotics at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Half of the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium every 4–5 days. Neurons were transfected on day 8 using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with the following modifications. Briefly, 1–2 μg of plasmid DNA and 4 μL of Lipofectamine 2000 were added to 100 μL of NbActive4 medium to make the transfection medium. Half of the culture medium was removed and combined with an equal volume of fresh NbActiv4 medium to make a 1:1 mixture. All dishes were replenished with conditioned (at 37 °C and 5% CO2) NbActiv4 medium. Following the addition of transfection medium, cells were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 2–3 h. The medium was then replaced using conditioned 1:1 mixture medium. Cells were imaged 36–72 h after transfection. Fluorescence imaging was performed in HHBSS buffer using a Zeiss microscope with a 40× objective or Olympus FV1000 microscope with a 20× objective. Neuron images were acquired and processed using Olympus FluoView.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as individual data points or mean ± SD. Sample sizes (n) are listed for each experiment. For Figs. 1e, 2e, 3f, and Supplementary Fig. 1c, t-tests were used with p values indicated in the figures.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

S.-Y.W. is supported by a NSERC graduate scholarship and an Alberta Innovates Technology Futures scholarship. Work in the lab of R.E.C. is supported by grants from CIHR (FS 154310), NSERC (RGPIN 288338-2010), NIH (U01 NS094246 and U01 NS090565), and Brain Canada. K.B. acknowledges support by NSERC (RGPIN-2014-06484). M.D. acknowledges support from NIH (R01NS080833, R01AI132387, R01AI139087, R21NS106159), the NIH-funded Harvard Digestive Disease Center (P30DK034854), and Boston Children’s Hospital Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (P30HD18655). M.D. holds the Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. We thank the University of Alberta Molecular Biology Services Unit for technical support, Dr. Christopher W. Cairo for providing access to instrumentation, and Dr. Matthew D. Wiens for helpful discussion regarding the manuscript.

Author contributions

Y.S. performed design and construction of the indicators. Y.S., S.-Y.W. and A.A. performed in vitro characterization. Y.S, S.-Y.W. and S.-I.M. performed plasmid construction. Y.S. and S.-Y.W. performed live imaging in mammalian cell lines. V.R. and Y.Q. performed imaging in dissociated neurons. Y.S., K.B., R.E.C. and M.D. supervised the research. Y.S., R.E.C. and M.D. wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

The data supporting this research are available in Supplementary Data 1. Plasmid constructs encoding KIRIN1, KIRIN1-GR, and GINKO1 are available through Addgene.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yi Shen, Email: yi.shen@ualberta.ca.

Robert E. Campbell, Email: robert.e.campbell@ualberta.ca

Min Dong, Email: min.dong@childrens.harvard.edu.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s42003-018-0269-2.

References

- 1.Palmer BF. Regulation of potassium homeostasis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015;10:1050–1060. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08580813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Padmawar P, Yao X, Bloch O, Manley GT, Verkman AS. K + waves in brain cortex visualized using a long-wavelength K+-sensing fluorescent indicator. Nat. Methods. 2005;2:825–827. doi: 10.1038/nmeth801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Florence G, Pereira T, Kurths J. Extracellular potassium dynamics in the hyperexcitable state of the neuronal ictal activity. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2012;17:4700–4706. doi: 10.1016/j.cnsns.2011.06.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sica DA, et al. Importance of potassium in cardiovascular disease. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2002;4:198–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2002.01728.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warny M, Kelly CP. Monocytic cell necrosis is mediated by potassium depletion and caspase-like proteases. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276:C717–C724. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.3.C717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yaron JR, et al. K(+) regulates Ca(2+) to drive inflammasome signaling: dynamic visualization of ion flux in live cells. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1954. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groß CJ, et al. K(+) efflux-independent NLRP3 inflammasome activation by small molecules targeting mitochondria. Immunity. 2016;45:761–773. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rastegar A, Soleimani M, Rastergar A. Hypokalaemia and hyperkalaemia. Postgrad. Med. J. 2001;77:759–764. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.77.914.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatterjee R, Yeh HC, Edelman D, Brancati F. Potassium and risk of Type 2 diabetes. Expert Rev. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;6:665–672. doi: 10.1586/eem.11.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frant MS, Ross JW., Jr. Potassium ion specific electrode with high selectivity for potassium over sodium. Science. 1970;167:987–988. doi: 10.1126/science.167.3920.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minta A, Tsien RY. Fluorescent indicators for cytosolic sodium. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:19449–19457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rimmele TS, Chatton JY. A novel optical intracellular imaging approach for potassium dynamics in astrocytes. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e109243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou X, et al. A new highly selective fluorescent K+sensor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:18530–18533. doi: 10.1021/ja207345s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kong X, et al. A highly selective mitochondria-targeting fluorescent K(+) sensor. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2015;54:12053–12057. doi: 10.1002/anie.201506038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashraf KU, et al. The potassium binding protein Kbp Is a cytoplasmic potassium sensor. Structure. 2016;24:741–749. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2016.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeats C, Bateman A. The BON domain: a putative membrane-binding domain. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:352–355. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buist G, Steen A, Kok J, Kuipers OP. LysM, a widely distributed protein motif for binding to (peptido)glycans. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;68:838–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlson HJ, Campbell RE. Genetically encoded FRET-based biosensors for multiparameter fluorescence imaging. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2009;20:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindenburg L, Merkx M. Engineering genetically encoded FRET sensors. Sensors. 2014;14:11691–11713. doi: 10.3390/s140711691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frommer WB, Davidson MW, Campbell RE. Genetically encoded biosensors based on engineered fluorescent proteins. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:2833–2841. doi: 10.1039/b907749a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell RE. Fluorescent-protein-based biosensors: modulation of energy transfer as a design principle. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:5972–5979. doi: 10.1021/ac802613w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baird GS, Zacharias DA, Tsien RY. Circular permutation and receptor insertion within green fluorescent proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:11241–11246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao Y, et al. An expanded palette of genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators. Science. 2011;333:1888–1891. doi: 10.1126/science.1208592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyawaki A, et al. Fluorescent indicators for Ca2+ based on green fluorescent proteins and calmodulin. Nature. 1997;388:882–887. doi: 10.1038/42264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindenburg LH, Vinkenborg JL, Oortwijn J, Aper SJA, Merkx M. MagFRET: the first genetically encoded fluorescent Mg2+sensor. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e82009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dittmer PJ, Miranda JG, Gorski JA, Palmer AE. Genetically encoded sensors to elucidate spatial distribution of cellular zinc. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:16289–16297. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900501200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conley JM, Radhakrishnan S, Valentino SA, Tantama M. Imaging extracellular ATP with a genetically-encoded, ratiometric fluorescent sensor. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0187481. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hires SA, Zhu Y, Tsien RY. Optical measurement of synaptic glutamate spillover and reuptake by linker optimized glutamate-sensitive fluorescent reporters. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:4411–4416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712008105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okumoto S, et al. Detection of glutamate release from neurons by genetically encoded surface-displayed FRET nanosensors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:8740–8745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503274102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lundby A, Mutoh H, Dimitrov D, Akemann W, Knöpfel T. Engineering of a genetically encodable fluorescent voltage sensor exploiting fast Ci-VSP voltage-sensing movements. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao X, Zhang J. Spatiotemporal analysis of differential Akt regulation in plasma membrane microdomains. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:4366–4373. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e08-05-0449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Imamura H, et al. Visualization of ATP levels inside single living cells with fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based genetically encoded indicators. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:15651–15656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904764106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bischof H, et al. Novel genetically encoded fluorescent probes enable real-time detection of potassium in vitro and in vivo. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1422. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01615-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Markwardt ML, et al. An improved cerulean fluorescent protein with enhanced brightness and reduced reversible photoswitching. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagai T, Yamada S, Tominaga T, Ichikawa M, Miyawaki A. Expanded dynamic range of fluorescent indicators for Ca(2+) by circularly permuted yellow fluorescent proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:10554–10559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400417101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cranfill PJ, et al. Quantitative assessment of fluorescent proteins. Nat. Methods. 2016;13:557–562. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fritz RD, et al. A versatile toolkit to produce sensitive FRET biosensors to visualize signaling in time and space. Sci. Signal. 2013;6:rs12. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bajar BT, et al. Improving brightness and photostability of green and red fluorescent proteins for live cell imaging and FRET reporting. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:20889. doi: 10.1038/srep20889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakai J, Ohkura M, Imoto K. A high signal-to-noise Ca2+probe composed of a single green fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:137–141. doi: 10.1038/84397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qian, Y., Rancic, V., Wu, J., Ballanyi, K. & Campbell, R. E. A bioluminescent Ca2+ indicator based on a topological variant of GCaMP6s. Chembiochem. 10.1002/cbic.201800255 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Wu J, et al. Genetically encoded glutamate indicators with altered color and topology. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018;13:1832–1837. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.7b01085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barykina NV, et al. A new design for a green calcium indicator with a smaller size and a reduced number of calcium-binding sites. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:34447. doi: 10.1038/srep34447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andersson B, Janson V, Behnam-Motlagh P, Henriksson R, Grankvist K. Induction of apoptosis by intracellular potassium ion depletion: using the fluorescent dye PBFI in a 96-well plate method in cultured lung cancer cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2006;20:986–994. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ohtsuka K, et al. Fluorescence imaging of potassium ions in living cells using a fluorescent probe based on a thrombin binding aptamer–peptide conjugate. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:4740–4742. doi: 10.1039/c2cc30536d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dirnagl U, Iadecola C, Moskowitz MA. Pathobiology of ischaemic stroke: an integrated view. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:391–397. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(99)01401-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu SP, Yeh C, Strasser U, Tian M, Choi DW. NMDA receptor-mediated K+ efflux and neuronal apoptosis. Science. 1999;284:336–339. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hösli L, Hösli E, Landolt H, Zehntner C. Efflux of potassium from neurones excited by glutamate and aspartate causes a depolarization of cultured glial cells. Neurosci. Lett. 1981;21:83–86. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(81)90062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ballanyi K, Grafe P. An intracellular analysis of gamma-aminobutyric-acid-associated ion movements in rat sympathetic neurones. J. Physiol. 1985;365:41–58. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grafe P, Ballanyi K. Cellular mechanisms of potassium homeostasis in the mammalian nervous system. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1987;65:1038–1042. doi: 10.1139/y87-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ballanyi K, Grafe P, ten Bruggencate G. Ion activities and potassium uptake mechanisms of glial cells in guinea-pig olfactory cortex slices. J. Physiol. 1987;382:159–174. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Belhage B, Hansen GH, Schousboe A. Depolarization by K+ and glutamate activates different neurotransmitter release mechanisms in GABAergic neurons: vesicular versus non-vesicular release of GABA. Neuroscience. 1993;54:1019–1034. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90592-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shen Y, et al. A genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator based on circularly permutated sea anemone red fluorescent protein eqFP578. BMC Biol. 2018;16:9. doi: 10.1186/s12915-018-0480-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuffler SW. Neuroglial cells: physiological properties and a potassium mediated effect of neuronal activity on the glial membrane potential. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1967;168:1–21. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1967.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ransom BR, Goldring S. Ionic determinants of membrane potential of cells presumed to be glia in cerebral cortex of cat. J. Neurophysiol. 1973;36:855–868. doi: 10.1152/jn.1973.36.5.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henn FA, Haljamäe H, Hamberger A. Glial cell function: active control of extracellular K+ concentration. Brain Res. 1972;43:437–443. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(72)90399-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Horio Y. Potassium channels of glial cells: distribution and function. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 2001;87:1–6. doi: 10.1254/jjp.87.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Olsen ML, et al. New insights on astrocyte ion channels: critical for homeostasis and neuron-glia signaling. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:13827–13835. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2603-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Horikawa K, et al. Spontaneous network activity visualized by ultrasensitive Ca(2+) indicators, yellow Cameleon-Nano. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:729–732. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thestrup T, et al. Optimized ratiometric calcium sensors for functional in vivo imaging of neurons and T lymphocytes. Nat. Methods. 2014;11:175–182. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lam AJ, et al. Improving FRET dynamic range with bright green and red fluorescent proteins. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:1005–1012. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nguyen AW, Daugherty PS. Evolutionary optimization of fluorescent proteins for intracellular FRET. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:355–360. doi: 10.1038/nbt1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burnier JV, et al. Engineering of weak helper interactions for high-efficiency FRET probes. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:1021–1027. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shaner NC, et al. A bright monomeric green fluorescent protein derived from Branchiostoma lanceolatum. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:407–409. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bindels DS, et al. mScarlet: a bright monomeric red fluorescent protein for cellular imaging. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:53–56. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barnett LM, Hughes TE, Drobizhev M. Deciphering the molecular mechanism responsible for GCaMP6m’s Ca2+-dependent change in fluorescence. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0170934. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen TW, et al. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature. 2013;499:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Enger R, et al. Dynamics of ionic shifts in cortical spreading depression. Cereb. Cortex. 2015;25:4469–4476. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ding F, et al. Changes in the composition of brain interstitial ions control the sleep-wake cycle. Science. 2016;352:550–555. doi: 10.1126/science.aad4821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.He Y, Hara H, Núñez G. Mechanism and regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016;41:1012–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this research are available in Supplementary Data 1. Plasmid constructs encoding KIRIN1, KIRIN1-GR, and GINKO1 are available through Addgene.