Abstract

Photoperiod response of flowering determines plant adaptation to different latitudes. Soybean, a short-day plant, has gained the ability to flower under long-day conditions during the growing season at higher latitudes, mainly through dysfunction of phytochrome A genes (E3 and E4) and the floral repressor E1. In this study, we identified a novel molecular genetic basis of photoperiod insensitivity in Far-Eastern Russian soybean cultivars. By testcrossing these cultivars with a Canadian cultivar Harosoy near-isogenic line for a recessive e3 allele, followed by association tests and fine mapping, we determined that the insensitivity was inherited as a single recessive gene located in an 842-kb interval in the pericentromeric region of chromosome 4, where E1-Like b (E1Lb), a homoeolog of E1, is located. Sequencing analysis detected a single-nucleotide deletion in the coding sequence of the gene in insensitive cultivars, which generated a premature stop codon. Near-isogenic lines (NILs) for the loss-of-function allele (designated e1lb) exhibited upregulated expression of soybean FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) orthologs, FT2a and FT5a, and flowered earlier than those for E1Lb under long-day conditions in both the e3/E4 and E3/E4 genetic backgrounds. These NILs further lacked the inhibitory effect on flowering by far-red light–enriched long-day conditions, which is mediated by E4, but not that of red-light–enriched long-day conditions, which is mediated by E3. These findings suggest that E1Lb retards flowering under long-day conditions by repressing the expression of FT2a and FT5a independently of E1. This loss-of-function allele can be used as a new resource in breeding of photoperiod-insensitive cultivars, and may improve our understanding of the function of the E1 family genes in the photoperiod responses of flowering in soybean.

Keywords: soybean, Glycine max, flowering, E1Lb, photoperiodism, adaptation

Introduction

Photoperiod response of flowering determines the adaptation of crops to a wide range of latitudes with different daylengths during growing seasons. Its regulatory mechanisms vary with plant species, and may rely on both evolutionally conserved and species-specific gene systems. In Arabidopsis, a long-day (LD) plant, CONSTANS (CO) plays a key role in regulation of photoperiodic flowering; transcriptional and post-translational regulation of CO results in accumulation of the CO protein in the late afternoon under LD conditions, which in turn activates FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) florigen gene expression (reviewed by Andrés and Coupland, 2012; Song et al., 2013). Similarly, in rice, a short-day (SD) plant, a CO ortholog, Heading date 1 (Hd1) (Yano et al., 2000), regulates the FT orthologs Heading date 3a (Hd3a) and Rice FT-like 1 (RFT1) (Kojima et al., 2002; Tamaki et al., 2007). However, unlike in Arabidopsis, Hd1 activates Hd3a expression under inductive SD conditions, but suppresses it under non-inductive LD conditions (Izawa et al., 2002). This functional switch, which is absent in Arabidopsis, is controlled by a complex of Hd1 with the monocot-specific CCT domain protein Grain number, plant height and heading date 7 (Ghd7) (Xue et al., 2008); Ghd7 represses the expression of the B-type response regulator Early heading date 1 (Ehd1) (Doi et al., 2004), an activator of Hd3a and RFT1 expression, by binding to its cis-regulatory region (Nemoto et al., 2016).

Soybean (Glycine max) has multiple CO orthologs (Fan et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2014), of which two pairs of homoeologs, CO-like (COL) 1a/COL1b and COL2a/COL2b, fully complement the function of CO in Arabidopsis (Wu et al., 2014). COL1a overexpression in soybean causes late flowering, and artificial COL1b mutants flower significantly earlier than the wild type, indicating that both COL1a and COL1b function as floral suppressors under LD conditions, as in rice (Cao et al., 2015). However, unlike in the case of Hd1, the overexpression of COL1a does not promote flowering under inductive SD conditions, although it up-regulates major soybean FT orthologs, FT2a and FT5a (Kong et al., 2010; Cao et al., 2015).

Despite the conserved roles of CO and COL genes across plant species in photoperiodic flowering, there is no report that any COL genes are involved in the genetic variation of flowering time in soybean. Among the 11 major genes for flowering that have been reported so far (E1–E9 and J, reviewed by Cao et al., 2017; E10, Samanfar et al., 2017), four maturity genes, E1 to E4, are the main contributors to soybean adaptation to a wide range of latitudes (Liu et al., 2011; Jia et al., 2014; Jiang et al., 2014; Langewisch et al., 2014; Tsubokura et al., 2014; Zhai et al., 2014; Lu et al., 2015; Kurasch et al., 2017; Li et al., 2017). The floral repressor E1 encodes a protein that contains a bipartite nuclear localization signal and a region distantly related to the B3 domain, and is a possible transcription factor that represses FT2a and FT5a expression (Xia et al., 2012). E1 expression is up-regulated under LD conditions under the control of the phytochrome A (phyA) proteins E3 and E4 (Liu et al., 2008; Watanabe et al., 2009; Xia et al., 2012). E2, a soybean ortholog of Arabidopsis GIGANTEA (GI) (Watanabe et al., 2011), inhibits flowering under LD conditions through a pathway distinct from the phyA-regulated E1 pathway (Xu et al., 2015; reviewed by Cao et al., 2017). E1 has two homologs, E1-like-a (E1La) and E1Lb, encoded 10,640 kb apart from each other in the homoeologous region of chromosome 4 (Xia et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2015). Down-regulation of the E1L genes by virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) in a cultivar deficient in the E1 gene leads to early flowering and abolishes the night-break response, suggesting that the two E1L genes are also involved in the photoperiod responses of soybean (Xu et al., 2015).

Photoperiod insensitivity in soybean is conditioned by combinations of various alleles at E1, E3, and E4 (Tsubokura et al., 2013, 2014; Xu et al., 2013; Zhai et al., 2015). E3 and E4 were originally identified as major genes for different responses of flowering to artificially induced LD conditions, where natural daylength was extended to 20 h with red light (R)-enriched cool white fluorescent lamps (fluorescent-long daylength; FLD) or far red light (FR)-enriched incandescent lamps (incandescent-long daylength; ILD) (Buzzell, 1971; Buzzell and Voldeng, 1980; Saindon et al., 1989). e3 conditions flowering under the FLD condition (Buzzell, 1971), whereas e4 does so under the ILD condition in the e3 background (Saindon et al., 1989), suggesting that E3 and E4 are functionally diverged and have an epistatic relationship. On the basis of the functions of alleles at the three loci, Xu et al. (2013) classified ILD-insensitive cultivars into three genotypic groups: (group 1) the dysfunction of both E3 and E4; (group 2) the dysfunction of E1 in combination with that of either E3 or E4; and (group 3) a combination of e1-as (hypomorphic allele), e3, and E4. Because E4 inhibits flowering under ILD conditions (Saindon et al., 1989; Cober et al., 1996; Abe et al., 2003; Liu and Abe, 2010), the group 3 cultivars have novel genes that abolish or reduce ILD sensitivity. One such gene is an early-flowering allele at qDTF-J, a QTL for days to flowering in linkage group J, which encodes FT5a; early flowering is caused by its increased transcriptional activity or mRNA stability associated with an insertion in the promoter and/or deletions in the 3′ UTR (Takeshima et al., 2016). Here, we describe a novel loss-of-function allele at the E1Lb locus, which is most likely involved in the gain of photoperiod insensitivity in group 3 soybean cultivars. Our data suggest that E1Lb inhibits flowering under LD conditions, independently of E1, and play major roles in the control of flowering in soybean.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Segregation Analysis

The indeterminate Far-Eastern Russian soybean cultivars Zeika (ZE), Yubileinaya (YU), and Sonata were crossed with the Canadian indeterminate cultivar Harosoy (L58-266; HA); ZE and YU were also crossed with a Harosoy near-isogenic line (NIL) for e3 (PI547716; H-e3). The three Russian cultivars have the same genotype as H-e3 at five maturity loci, E1, E2, E3, E4, and E9 (e1-as/e2/e3/E4/E9), but unlike H-e3 they flower without any marked delay under ILD conditions in comparison with natural daylength (ND) conditions (maximum daylength, 15.2 h) in Sapporo, Japan (43°07′N, 141°35′E) (Xu et al., 2013). The ILD condition was set at an experimental farm of Hokkaido University by extending the ND to 20 h by supplemental lighting from 2:00 to 7:00 and from 18:00 to 22:00 with incandescent lamps with a red-to-far-red (R:FR) quantum ratio of 0.72 (Abe et al., 2003). Seeds of F2 populations and parents were sown in paper pots (Paperpots No. 2, Nippon Beet Sugar Manufacturing Co., Tokyo, Japan) on 28 May 2013 for the crosses with HA and 26 May 2014 for crosses with H-e3. The pots were put under the ILD condition, and 12 days later seedlings were transplanted into soil. The progeny test was carried out for 48 F2 plants randomly selected from the H-e3 × ZE cross and recombinant plants used in fine mapping. Seeds of these plants were sown in paper pots on late May in 2015 to 2017 (25 May, 2015; 28 May, 2016; and 26 May, 2017). After 12 days under the ILD condition, 15 seedlings per plant were transplanted into the same field. The number of days from sowing to the first flower opening (R1) (Fehr et al., 1971) of each plant was recorded.

Association Test, Linkage Map Construction, and Fine Mapping

A total of 16 F2 plants from the H-e3 × ZE cross were used to test the association of ILD sensitivity with simple sequence repeat (SSR) marker genotypes. They were selected based on the segregation pattern in their progeny, and included 8 plants fixed for ILD insensitivity and 8 plants fixed for ILD sensitivity. SSR markers were chosen from those located in genomic regions that harbored the soybean orthologs of Arabidopsis flowering genes (Song et al., 2004; Watanabe et al., 2012). The SSR markers significantly associated with ILD sensitivity were genotyped for a total of 306 F2 plants from the H-e3 × ZE and H-e3 × YU crosses to confirm the detected association. Plants recombinant in the targeted region were subjected to fine mapping; the genotypes for the target gene were estimated based on the segregation of flowering under the ILD condition in the progeny and were compared with the graphical genotypes constructed by using additional 11 BARCSOY SSR markers (Song et al., 2010) (Supplementary Table S1).

Development of NILs

Four sets of NILs, each including one NIL for ILD insensitivity and another one for sensitivity, were developed from heterozygous inbred F5 plants derived from different F2 plants (#4 and #21) from the H-e3 × ZE cross and those (#11 and #20) from the HA × ZE cross. The former two sets of NILs had the recessive e3 allele, whereas the latter two had the dominant E3 allele. These lines, together with parents and an ILD-insensitive NIL of HA for e3 and e4 (PI546043; H-e3e4), were cultivated in a growth chamber (25°C, 20-h daylength) with an average photon flux of 120 μmol m-2 s-1 and an R:FR ratio of 2.2 at 1 m below light sources, or in the field under the ILD condition (sowing date, May 26, 2018), as described above. For comparison, indeterminate NILs for alleles, e1-nl and e1-as, at E1 (NIL-E1; e2/E3/E4/E9), which were developed from a heterozygous inbred F5 plant derived from a cross between the Japanese determinate cultivar Toyomusume (e1-nl/e2/E3/E4/e9) and HA, were included in the evaluation of flowering under the ILD condition.

DNA Extraction and SSR Marker Analysis

Total DNA was extracted from trifoliate leaves of each of 150 H-e3 × ZE and 156 H-e3 × YU F2 plants as described by Doyle and Doyle (1990), and from each of 492 seeds from two F2 plants from the H-e3 × ZE cross, as described by Xia et al. (2012). Each PCR mixture for SSR marker analysis contained 30 ng of total genomic DNA as a template, 0.2 μl of each primer (10 μM), 0.8 μl of dNTPs (2.5 mM), 0.1 μl of Taq DNA polymerase (Ampliqon), and 1 μl of 10× ammonium buffer (Ampliqon) in a total volume of 10 μl; amplification conditions were 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in 10.5% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized under UV light.

Expression Analysis

A new fully expanded leaflet was sampled from each of four plants per parent and NIL at Zeitgeber time 3 in two different growing stages, the 2nd and 3rd leaf stages. The sampled leaves were bulked, immediately frozen in liquid N2, and stored at -80°C. Total RNA was isolated from frozen tissues with TRIzol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). DNase I (Takara) was used to remove genomic DNA. The complementary DNAs (cDNAs) were synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA by using the M-MLV reverse transcriptase system (Invitrogen) with an oligo (dT) 20 primer in a volume of 20 μL. Transcript levels of E1, E1La, E1Lb, FT2a, and FT5a were determined by quantitative real-time PCR. The PCR mixture (20 μL) contained 0.1 μL of the cDNA synthesis reaction mixture, 5 μL of 1.2 μM primer premix, and 10 μL SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Takara). A CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad) was used. The PCR cycling conditions were 95°C for 3 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 59°C for 30 s, 72°C for 20 s, and 78°C for 2 s. Fluorescence was quantified before and after the incubation at 78°C to monitor the formation of primer dimers. The mRNA for β-tubulin was used for normalization. A reaction mixture without reverse transcriptase was also used as a control to confirm the absence of genomic DNA contamination. Amplification of a single DNA fragment was confirmed by melting curve analysis and gel electrophoresis of the PCR products. Averages and standard errors of relative expression levels were calculated from PCR results for three independently synthesized cDNAs. Primer sequences used in expression analyses are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Sequencing and Marker Analysis of E1Lb

The coding sequences of the three gene models, Glyma.04G143300, Glyma.04G143400 and Glyma.04G143500, were analyzed for H-e3 and ZE. The coding sequences were amplified from the cDNAs by using primers listed in Supplementary Table S1. The amplified fragments were cloned into a pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega) and sequenced with a BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing kit and an ABI PRISM 3100 Avant Genetic Analyzer (both from Applied Biosystems, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A derived cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence (dCAPS) marker targeting a single-base deletion observed in ZE was developed to discriminate the functional E1Lb allele of H-e3 from the loss-of-function e1lb allele of ZE. The 275-bp DNA fragment amplified from ZE by PCR with the forward primer 5′-GTGTAAACACTCAAAGTCCTT-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-CGTCTTCTTGATCTTCCAACG-3′ was digested with HpyCH4IV (New England Biolabs Japan) into two fragments, 254 bp and 21 bp, but the 276-bp fragment amplified from H-e3 was resistant to HpyCH4IV digestion. The PCR products were treated with HpyCH4IV for 1 h and then separated by electrophoresis in 2.5% NuSieve 3:1 gel (Lonza), stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized under UV light.

Survey of the Dysfunctional Allele in ILD-Insensitive Accessions

A total of 62 ILD-insensitive accessions including the three Russian cultivars were surveyed for the E1Lb genotype using the allele-specific DNA marker. They included 9 accessions from northern Japan, 26 from north-eastern China, 16 from Far-Eastern Russia, 8 from Ukraine, and 3 from Poland (Supplementary Table S2). The maturity genotypes at E1 to E4 of 50 accessions were determined previously by Xu et al. (2013), and those of the remaining 12 accessions were assayed according to Xu et al. (2013) and Tsubokura et al. (2014).

Results

Segregation of Flowering Time in F2 and F3 Populations

The three Russian cultivars are photoperiod insensitive (Xu et al., 2013). They flowered 45–47 days after sowing (DAS) under the ND condition of Sapporo, whereas H-e3 and HA flowered approximately 5 and 10 days later, respectively. Under the ILD condition, the three cultivars and H-e3 flowered 2–4 days and around 20 days later than under ND, respectively, whereas HA continued vegetative growth and did not develop any flower buds until the end of light supplementation (10 August, 76 DAS).

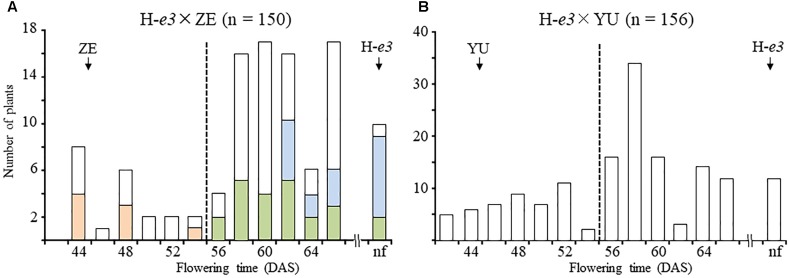

Flowering time under the ILD condition in F2 populations of the H-e3 × ZE and H-e3 × YU crosses varied continuously from that of ILD-insensitive parents (45 DAS for ZE and 46 DAS for YU) to the end of light supplementation; 10 out of 150 and 12 out of 156 plants had no flower buds in the H-e3 × ZE and H-e3 × YU F2 populations, respectively (Figure 1). In both populations, the distribution of flowering time tended to be bi-modal; plants which flowered at 56 DAS and later or remained vegetative segregated more than those which flowered earlier. We randomly selected 48 H-e3 × ZE F2 plants and tested their progeny for flowering time segregation under the ILD condition. Based on the segregation pattern, the 48 F2 plants could be classified into three groups: (1) plants fixed for ILD insensitivity (all F3 plants tested flowered as ZE did; e/e); (2) those segregating for flowering time (E/e) and (3) those fixed for ILD sensitivity (all F3 plants tested showed delayed or no flowering; E/E) (Figure 1A). The number of plants was 8 in e/e, 23 in E/e, and 17 in E/E, in consistence with a monogenic 1:2:1 ratio (χ2 = 3.81, df = 2, p = 0.18), suggesting the involvement of a single recessive gene for ILD insensitivity. Based on the results of the progeny test, we classified 306 F2 plants into early-flowering ILD-insensitive plants, which flowered before 56 DAS, and late- or non-flowering ILD-sensitive plants (Figure 1). The segregation ratios of the two classes fit the expected 3:1 ratio (χ2 = 0.33, df = 1, p = 0.56 for H-e3 × ZE, χ2 = 3.28, df = 1, p = 0.07 for H-e3 × YU), confirming that ILD insensitivity is controlled mainly by a single recessive gene.

FIGURE 1.

Segregation of flowering time in F2 populations of crosses between a Harosoy NIL for e3 (H-e3) and the incandescent-long daylength (ILD)-insensitive cultivars Zeika (ZE) and Yubileinaya (YU) under far red light–enriched ILD conditions. (A) H-e3 × ZE; (B) H-e3 × YU. In a cross between H-e3 and ZE, 48 F2 plants were selected for the progeny test; ILD-sensitivity genotypes were estimated based on the segregation in the progeny. Pink bars, homozygotes for ILD insensitivity (e/e); yellow–green bars, heterozygotes (E/e); light-blue bars, homozygotes for ILD sensitivity (E/E). Arrows indicate mean values of flowering time in parents. Dotted vertical lines indicate the threshold for classification of F2 plants into early-flowering ILD-insensitive and late- or non-flowering ILD-sensitive. nf, no flower buds by the end of light supplementation. DAS, days after sowing.

We also examined the segregation of flowering time under the ILD condition for the crosses between HA and the three Russian cultivars. Because HA had the E3 allele and the three cultivars had the e3 allele, we predicted that, in addition to the gene for ILD insensitivity segregated in the crosses with H-e3, the E3 locus would also segregate in the F2 populations. In the three crosses, however, ILD-insensitive plants segregated at frequencies of 21.1–33.9%; the remaining plants remained vegetative until the end of light supplementation (Table 1). These segregation frequencies were thus inconsistent with those of a two-gene model, but were close to those expected from monogenic inheritance, as in the crosses with H-e3 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Segregation of ILD-insensitivity in F2 of crosses of an ILD-sensitive cultivar Harosoy with ILD-insensitive Russian cultivars.

| Cross combination | Number of plants |

χ2 value for 1:3 | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ILD-insensitive | ILD-sensitive | Total | |||

| Harosoy × Zeika | 19 | 37 | 56 | 3.57 | 0.059 |

| Harosoy × Yubileinaya | 28 | 105 | 133 | 1.66 | 0.198 |

| Harosoy × Sonata | 19 | 54 | 73 | 0.06 | 0.803 |

Association Test, Linkage Map Construction, and Fine Mapping

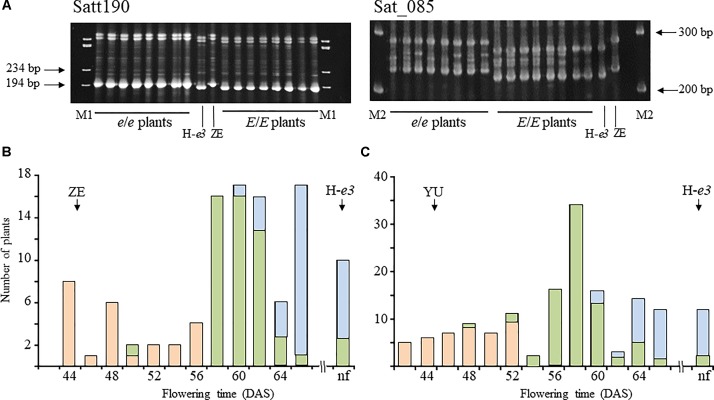

To determine the genomic position of the gene for ILD insensitivity from ZE, we tested the association between ILD sensitivity and SSR marker genotypes. Based on the results of the progeny test, we selected 16 F2 plants from the H-e3 × ZE cross, 8 homozygous for ILD insensitivity (e/e), and 8 homozygous for ILD sensitivity (E/E). Among the SSR markers tested, Satt190 and Sat_085 in linkage group C1 (chromosome 4; Chr04) showed genotypic variation in complete accordance with the ILD sensitivity (Figure 2A). Then we determined the genotypes of the two markers in the whole F2 plants of H-e3 × ZE and H-e3 × YU populations (Figures 2B,C). The two markers were tightly linked to each other with a recombination value of 2.1, and were closely associated with ILD sensitivity. All of the plants homozygous for the allele from ILD-insensitive parents at Sat_085 (I/I) flowered before 56 DAS (H-e3 × ZE) or 52 DAS (H-e3 × YU), whereas those homozygous for the allele from ILD-sensitive H-e3 (S/S) flowered at ≥60 DAS or did not flower in both crosses. Heterozygous plants (I/S) mostly flowered at ≥58 DAS (H-e3 × ZE) or ≥54 DAS (H-e3 × YU), which partly overlapped with the flowering date ranges of the S/S plants; only a few plants flowered as early as the I/I plants. These results strongly suggested that a gene for ILD insensitivity is located near the two SSR markers.

FIGURE 2.

Simple sequence repeat (SSR) marker analyses in F2 plants from a Harosoy isoline for e3 (H-e3) × Zeika (ZE) cross. (A) Gel electrophoresis for the analysis of Satt190 and Sat_085. Eight plants homozygous for the ILD-insensitive allele (e/e) and 8 plants homozygous for the ILD-sensitive allele (E/E) were selected on the basis of the results of the progeny test. M1, φX174/HaeIII digest; M2, 100 bp DNA ladder. (B,C) Association between Sat_085 and flowering time in H-e3 × ZE (B) and H-e3 × YU (C). F2 plants were classified based on the genotype at Sat_085. Pink bars, homozygotes for the allele from ILD-insensitive parents (I/I); yellow-green bars, heterozygotes (I/S); light-blue bars, homozygotes for the allele from ILD-sensitive H-e3 (S/S). Arrows indicate mean values of flowering time in parents. DAS, days after sowing.

Satt190 and Sat_085 are located 17.3 Mb from each other in the pericentromeric region of Chr04 (Schmutz et al., 2010) (Phytozome v12.1/Glycine max Wm82.a2.v1). To delimit the genomic region of the gene for ILD insensitivity more precisely, we selected plants with recombination between the two markers (7 from 306 F2 plants from the H-e3 × ZE and H-e3 × YU crosses and 3 from 492 F3 plants from the H-e3 × ZE cross) and constructed their graphical genotypes with 11 SSR markers. A comparison of the graphical genotypes with the genotype of ILD insensitivity estimated by the progeny test revealed that the gene for ILD insensitivity was located between SSR markers M5 (BARC-18g-0889) and M6 (BARC-18g-0895) (Figure 3). The physical distance between the two markers was 842 kb, and the delimited region contained only 6 annotated genes (Phytozome v12.1/Glycine max Wm82.a2.v1) (Figure 3 and Table 2). RNA-sequencing Atlas in Phytozome v12.1/Glycine max Wm82.a2.v1 indicates that Glyma.04G143000, Glyma.04G143100 and Glyma.04G143200 are expressed only in flower or root tissues, whereas Glyma.04G143300, Glyma.04G143400, and Glyma.04G143500 are expressed in leaves (Severin et al., 2010). Because ZE exhibited significantly higher expressions for FT2a and FT5a in leaves in the 2nd and 3rd trifoliate leaf stages than H-e3 under R-enriched LD condition (Supplementary Figure S1), we focused on the three genes expressed in leaves as a possible candidate of the gene for ILD insensitivity that upregulates the two FT genes.

FIGURE 3.

Fine mapping of a locus for ILD insensitivity (E/e) and annotated genes in the delimited region of Williams 82 chromosome 4 (Glycine max Wm82.a2.v1). M1 to M10, BARCSOY-SSR markers; Pink bars, homozygotes for the allele from ILD-insensitive parents (I/I); yellow–green bars, heterozygotes (I/S); light blue bars, homozygotes for the allele from ILD-sensitive H-e3 (S/S). The E genotype for ILD insensitivity was estimated from the segregation patterns in the progeny. Six genes annotated in the region between M5 and M6 are shown at the bottom.

Table 2.

Genes annotated in an 842-kb genomic region in chromosome 4 delimited by fine-mapping.

| No. | Gene | Annotation (Phytozome V12.1/Glycine max Wm82.a2.v1) | Expressed tissues |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | Glyma.04G143000 | Diacylglycerol kinase 7 | Flower |

| (2) | Glyma.04G143100 | RNA-binding (RRM/RBD/RNP motifs) family protein | Root |

| (3) | Glyma.04G143200 | Pectin lyase-like superfamily protein | Flower |

| (4) | Glyma.04G143300 | AP2/B3-like transcriptional factor family protein, E1Lb | Leaf |

| (5) | Glyma.04G143400 | Cytidine/deoxycytidylate deaminase family protein | Leaf, root |

| (6) | Glyma.04G143500 | Mitochondrial substrate carrier family protein | Flower, leaf |

Data on expressed tissues are referred from Glycine max Wm82.a2.v1. (Severin et al., 2010).

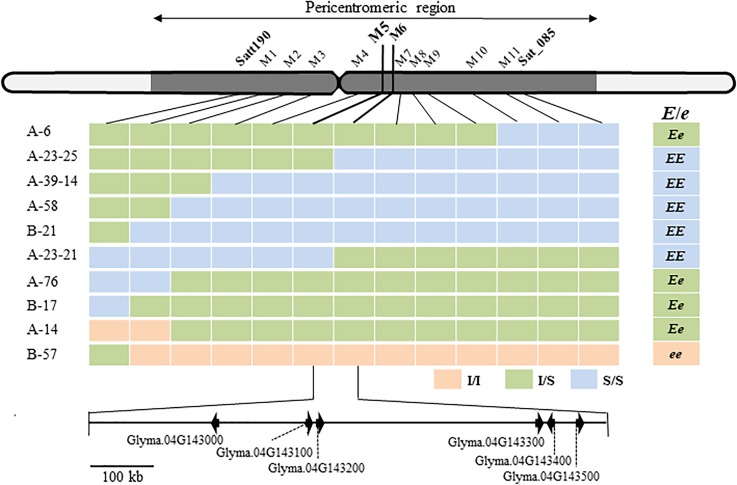

Sequence Analysis

Sequence analysis revealed that ZE and H-e3 possessed identical sequences for Glyma.04G143400 and Glyma.04G143500, whereas one of cytosines at the 162th nucleotide to 164th nucleotide from the adenine of the start codon was deleted in the Glyma.04G143300 from ZE; this deletion generated a premature stop codon, and the Glyma.04G143300 from ZE was predicted to encode a truncated protein of 61 amino acids (Figure 4). Glyma.04G143300 is E1Lb, one of two homoeologs (E1La and E1Lb) of floral repressor E1 (Xia et al., 2012). Because the down-regulation of E1La and E1Lb expressions by VIGS promotes flowering under non-inductive conditions such as LD and night break (Xu et al., 2015), we considered the loss-of-function allele of E1Lb (designated e1lb hereafter) as the most probable causal factor for the ILD-insensitivity.

FIGURE 4.

DNA and predicted amino acid sequences of Glyma.04G143300 (E1Lb) in Williams 82 (W82), Harosoy isoline for e3 (H-e3), and Zeika (ZE). (A) DNA sequences of the 138th nucleotide to 177th nucleotide from the adenine of the stat codon. One of cytosines at the 162th nucleotide to 164th nucleotide underlined was deleted in ZE. (B) Predicted amino acid sequences.

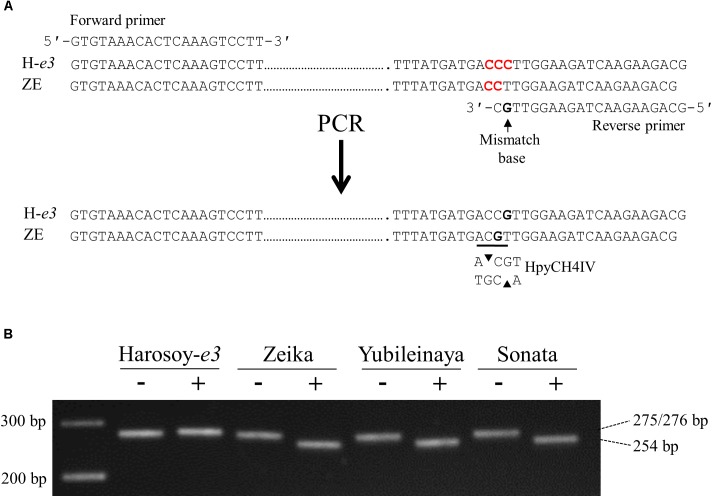

We developed a dCAPS marker to discriminate e1lb from E1Lb (Figure 5). The PCR-amplified fragment of 275 bp from ZE produced a shorter fragment of 254 bp when digested with HpyCH4IV, whereas that from H-e3 (276 bp) was not digested. The digestion of the PCR products from YU and Sonata (Russian cultivar) produced 254-bp fragments, indicating that these two cultivars had the same deletion as ZE (Figure 5B). Therefore, the segregation of ILD-insensitive plants in the crosses of these cultivars with HA and H-e3 were most likely caused by e1lb.

FIGURE 5.

Derived cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence (dCAPS) marker analysis to detect the single-base deletion in the e1lb allele. (A) Primers designed and the generation of an HpyCH4IV restriction site. One of three cytosines marked by red was deleted in ZE. (B) Gel electrophoresis of PCR products without (–) or with (+) HpyCH4IV digestion. H-e3, Harosoy NIL for e3; ZE, Zeika.

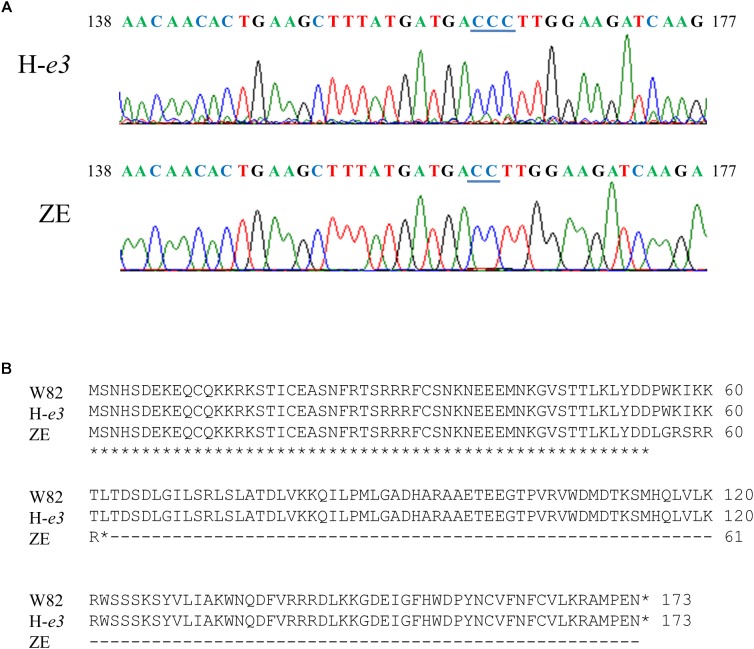

Comparison of Flowering Time and Gene Expression Among NILs

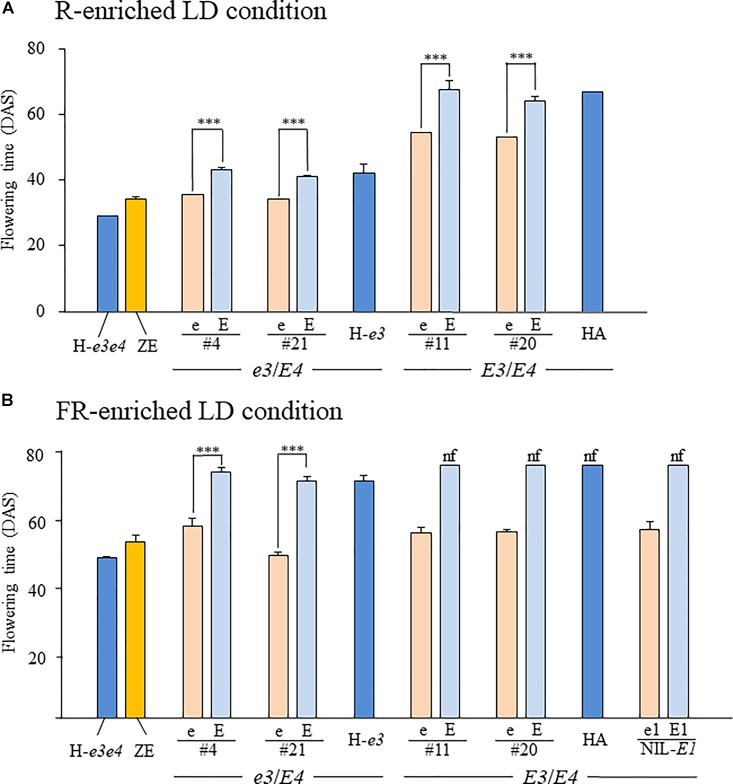

We evaluated the allelic effects of E1Lb and e1lb on flowering under the R-enriched LD condition (daylength, 20 h) in four sets of NILs, each for E1Lb and e1lb, developed from different F2 plants from the H-e3 × ZE cross (#4 and #21) and the HA × ZE cross (#11 and #20). In the two sets of the e3/E4 NILs, each NIL for e1lb flowered at the same or almost the same time (#4, 31.7 DAS; #21, 30.3 DAS) as ZE (30.3 DAS); this was on average 6.7–7.6 days earlier than the respective NILs for E1Lb, which flowered at almost the same time as H-e3 (Figure 6A). Flowering times of the E3/E4 NILs were around 20 days or more later than those of the e3/E4 NILs. e1lb also promoted flowering in the E3/E4 background: each NIL for e1lb flowered around 10 days earlier than the respective NIL for E1Lb and HA. This flowering-promoting effect of e1lb versus E1Lb under the R-enriched LD condition was smaller than that of e4 vs. E4 and that of e3 vs. E3, because H-e3e4 and H-e3 flowered, on average, 13 and 25 days earlier than H-e3 and HA (E3E4), respectively.

FIGURE 6.

Flowering time in NILs for the e1lb (e) and E1Lb (E) alleles under R-enriched and FR-enriched LD conditions. Two sets of NILs (#4 and #21) have the e3/E4 genotype, similar to H-e3, whereas the other two (#11 and #20) have the E3/E4 genotype, similar to HA. A set of E3/E4 NILs for e1-nl (e1) and e1-as (E1) at E1 locus (NIL-E1) were also evaluated for the flowering under the FR-enriched LD condition. Plants were grown under 20-h (A) R-enriched LD or (B) FR-enriched ILD conditions. Data are presented as mean and standard error (n = 5). nf, no flower buds by the end of light supplementation, DAS, days after sowing, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

We also evaluated the effect of e1lb vs. E1Lb on flowering under the FR-enriched ILD condition (Figure 6B). e1lb induced flowering at 58 DAS (#4) or 49 DAS (NILs #21) in the e3/E4 genetic background and at 56 DAS (#11 and #20) in the E3/E4 genetic background. All these NILs produced pods of up to 3 cm in length at the end of light supplementation, similar to those of ZE and H-e3e4. In contrast, the e3/E4 NILs for E1Lb and H-e3 flowered around 20 days later, and E3/E4 NILs for E1Lb and HA continued vegetative growth and did not produce any flower buds until the end of light supplementation. Therefore, e1lb was sufficient to induce flowering under the ILD condition, irrespective of the E3 genotype (Figure 6B). Interestingly, a similar flowering-promoting effect was observed in the NIL-E1 for a loss-of-function allele e1-nl (e1); it initiated flowering under the ILD condition, as the E3/E4 NILs for e1lb, whereas the NIL for e1-as (E1) did not (Figure 6B).

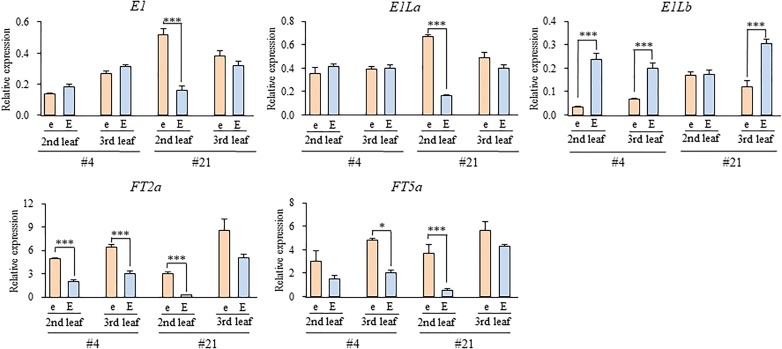

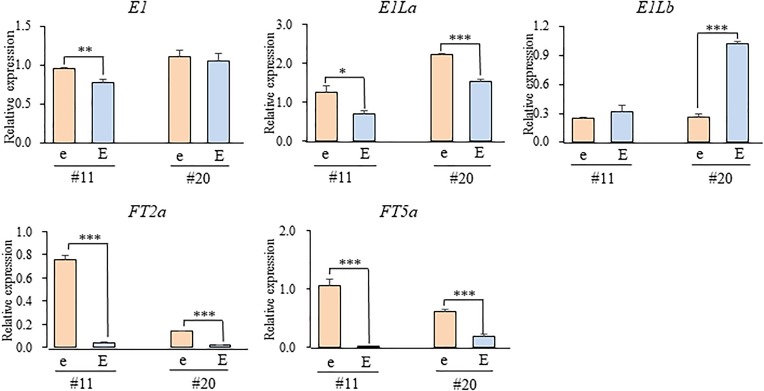

We tested the expression levels of E1, two E1L genes, and two FT orthologs in two different growing stages (the 2nd and 3rd leaf stages) in the e3/E4 NILs grown under the R-enriched LD condition (Figure 7). The expression levels of E1 and E1La were similar between the NILs for E1lb and e1lb at both stages in NILs #4 or at the 3rd stage in NILs #21; both E1 and E1La were significantly up-regulated in the 2nd leaf stage in NILs (#21) for e1lb relative to those for E1Lb. On the other hand, the expression of E1Lb was significantly down-regulated in the NILs for e1lb at both stages (#4) or at the 3rd leaf stage (#21). In contrast, the expression of both FT2a and FT5a was up-regulated at both stages in the NILs for e1lb relative to those for E1Lb in both NIL sets. The similar effect of e1lb vs. E1Lb on the expression of FT2a and FT5a was also observed at the 3rd leaf stage in both sets of E3/E4 NILs (#11 and #20; Figure 8). As observed in the e3/E4 NILs for e1lb, the expression levels of FT2a and FT5a were significantly upregulated in the E3/E4 NIL for e1lb.

FIGURE 7.

Expression levels of E1, E1-Like, and FT genes at the second and third leaf stages in two sets of e3/E4 NILs for the e1lb (e) and E1Lb (E) alleles under R-enriched LD (20 h) conditions. Relative mRNA levels (mean and standard error, n = 3) are expressed as the ratios to β-tubulin transcript levels. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.005.

FIGURE 8.

Expression levels of E1, E1-Like, and FT genes at the third leaf stage in two sets of E3/E4 NILs for the e1lb (e) and E1Lb (E) alleles under R-enriched LD (20 h) conditions. Relative mRNA levels (mean and standard error, n = 3) are expressed as the ratios to β-tubulin transcript levels. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.005.

Survey of the e1lb Allele in ILD-Insensitive Soybean Accessions

To determine whether or not the deletion in the E1Lb gene is region specific, we surveyed polymorphism in the ILD-insensitive soybean accessions analyzed for the genotypes of E1 to E4 by using the developed dCAPS marker. In addition to the three Russian cultivars, we found that another two Russian cultivars, Salyut 216 and DYA-1, had the e1lb allele, whereas all the other accessions had the functional E1Lb allele (Supplementary Table S2). All of Russian cultivars with e1lb possessed the maturity genotype of e1-as/e3/E4. There was no cultivar which has loss-of-function alleles at both E1 and E1Lb loci.

Discussion

The soybean maturity loci, E1 to E4, are major flowering loci that determine the ability of cultivars to adapt to different latitudes. Diverse allelic combinations at the E1, E3, and E4 loci, each of which has multiple loss-of-function alleles (Tsubokura et al., 2013, 2014; Xu et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2014; reviewed by Cao et al., 2017), have resulted in cultivars with various sensitivities to photoperiod. Photoperiod insensitivity is an adaptive trait for cultivars at high latitudes; such cultivars are classified into three genotypic groups according to the allelic functions at each of the three loci (Xu et al., 2013). Among the ILD accessions tested, the predominant group has the loss-of-function alleles of the phyA genes E3 and E4 (e3/e4), followed by a group which has the loss-of-function of the E1 repressor for FT2a and FT5a in combination with a dominant E3 or E4 allele. Cultivars of the third group have a novel genetic mechanism that abolishes or reduces sensitivity to daylength, because they have the same genotype (e1-as/e3/E4) as an HA NIL for e3, which is sensitive to FR-enriched ILD conditions (Saindon et al., 1989; Cober et al., 1996; Abe et al., 2003; Liu and Abe, 2010; Xu et al., 2013). Takeshima et al. (2016) carried out QTL analysis of ILD insensitivity by a testcross of a Chinese cultivar of group 3 with the HA NIL for e3 and demonstrated that an early-flowering allele at qDTF-J, which encodes the FT5a protein, up-regulates FT5a expression by cis-activation in the presence of E4 to induce flowering under ILD conditions.

In the present study, we detected a novel loss-of-function allele that resulted from a frameshift mutation at the E1Lb locus in Far-Eastern Russian group 3 photoperiod-insensitive cultivars. E1Lb and its tandemly linked homolog, E1La, have high sequence similarity to E1, suggesting their functional similarity, although a certain degree of subfunctionalization is suggested by the presence of a number of amino acid substitutions and indels between the E1 and E1L genes (Xia et al., 2012). Down-regulation by VIGS revealed that, similar to E1, E1L genes inhibit flowering under LD and night-break conditions (Xu et al., 2015), but the function of each homolog has remained undetermined. Comparison of NILs for E1Lb and e1lb in this study suggests that e1lb promotes flowering under both R-enriched and FR-enriched LD conditions. In particular, the effect of e1lb vs. E1Lb in the FR-enriched LD condition was similar to that of e4 vs. E4, irrespective of the E3 genotype, suggesting that e1lb completely cancels the inhibitory effect of FR-enriched LD on flowering modulated by E4. These flowering-promoting effects are most likely due to the up-regulation of FT2a and FT5a; their expression levels were not associated with the expression levels of E1 and E1La. One likely explanation for this observation is that the total expression level and/or activity of E1, E1La and E1lb may be important for the repression of FT2a and FT5a expression. The induction of flowering by e1lb in the E3/E4 genetic background under ILD conditions is in good accordance with monogenic segregation observed in the crosses of HA with Russian ILD-insensitive cultivars. e1lb also promoted flowering under R-enriched LD conditions, but its effect was small and it could not cancel flowering inhibition by E3 as efficiently as e3 did. The function of E1Lb may therefore depend on light quality of LD. Interestingly, e1-nl (loss-of-function allele at the E1 locus) could also cancel the inhibitory effect of FR-enriched LD conditions on flowering, as efficiently as e4 could. Because the effects of e1lb under the e1-as background were similar to those of e1-nl under the E1Lb background (Figure 6B), E1 and E1Lb may inhibit flowering under LD conditions, independently of each other. It may be tempting in a further study to develop double recessive lines for the loss-of-function alleles at the E1 and E1Lb loci not only to elucidate the interaction between the two genes and the function of another E1 homolog, E1La, but also to explore the regulatory mechanisms of these E1 family genes by E3 and E4 under different light conditions. In addition, a further study is also needed to determine why the loss-of-function allele at E1Lb can singly upregulate the FT2a and FT5a expression under LD condition, even though the remaining E1 family genes are expressed normally.

E1, E2, and E3 have large effects on flowering in a wide range of latitudes, whereas the allelic effect of E4 is rather limited to high latitudes (Yamada et al., 2012; Tsubokura et al., 2013, 2014; Xu et al., 2013; Lu et al., 2015). Among these four soybean genes, E1 has the most marked effect on time to flowering (McBlain et al., 1987; Upadhyay et al., 1994; Tsubokura et al., 2014). The polymorphism of E1 (or its flanking genomic region) largely accounts for the variation in flowering time and related agronomic traits in segregating populations of different genetic backgrounds (Yamanaka et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2004; Funatsuki et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2007; Zhai et al., 2015). In contrast to the E1 gene, only a few reports have demonstrated the presence of major genes or QTLs for flowering and maturing associated with the genomic region of Chr04 harboring E1La and E1Lb (Cober et al., 2010; Cheng et al., 2011; Watanabe et al., 2017; Kong et al., 2018). Cober et al. (2010) determined that the E8 gene, which was identified in a photoperiod-insensitive genetic background, is located in a genomic region harboring two E1L genes 10, 640 kb apart from each other (Xu et al., 2015), suggesting either of E1La and E1Lb as a candidate for E8. The QTLs for flowering and maturity were also detected in the positions of Chr04 similar to that of E8 (Cheng et al., 2011; Watanabe et al., 2017; Kong et al., 2018). It would be interesting to determine whether the E8 gene is E1La or E1Lb and to identify the responsible genes for these QTLs. Genotyping with an allele-specific DNA marker in this study revealed that e1lb is a rare and region-specific allele even in early maturing photoperiod-insensitive cultivars, suggesting that e1lb has neither largely contributed to the diversity of flowering behaviors nor been used widely in soybean breeding. The e1lb allele may therefore be useful as a new resource to broaden the genetic variability of soybean cultivars for flowering under LD conditions at high latitudes.

Author Contributions

JZ, BL, and JA conducted the experiments. JZ, RT, and KH conducted genetic analyses, fine-mapping, and sequencing analyses. JZ and MX developed allele-specific DNA markers and analyzed the variation of genotypes in soybean accessions. JZ, MX, and TY conducted the expression analyses. JZ and JA drafted the manuscript with edits from RT, KH, MX, FK, BL, TY, and AK. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Drs. AY Ala (All Russian Research Institute of Soybean, Russia) and ER Cober (Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Canada) for providing us seeds of soybean cultivars and experimental lines.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (17K07579) to JA, by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31501330) to MX, the Program of the General Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31771815) to BL, and by the Natural Key R&D Program of China (2017YFE0111000 and 2016YFD0100400) to FK.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2018.01867/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abe J., Xu D., Miyano A., Komatsu K., Kanazawa A., Shimamoto Y. (2003). Photoperiod-insensitive Japanese soybean landraces differ at two maturity loci. Crop Sci. 43 1300–1304. 10.2135/cropsci2003.1300 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andrés F., Coupland G. (2012). The genetic basis of flowering responses to seasonal cues. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13 627–639. 10.1038/nrg3291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzzell R. I. (1971). Inheritance of a soybean flowering response to fluorescent-daylength conditions. Can. J. Genet. Cytol. 13 703–707. 10.1139/g71-100 21556700 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buzzell R. I., Voldeng H. D. (1980). Inheritance of insensitivity to long daylength. Soyb. Genet. Newsl. 7 26–29. 10.1093/jhered/esp113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao D., Li Y., Lu S., Wang J., Nan H., Li X., et al. (2015). GmCOL1a and GmCOL1b function as flowering repressors in soybean under long-day conditions. Plant Cell Physiol. 56 2409–2422. 10.1093/pcp/pcv152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao D., Takeshima R., Zhao C., Liu B., Abe J., Kong F. (2017). Molecular mechanisms of flowering under long days and stem growth habit in soybean. J. Exp. Bot. 68 1873–1884. 10.1093/jxb/erw394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L., Wang Y., Zhang C., Wu C., Xu J., Zhu H., et al. (2011). Genetic analysis and QTL detection of reproductive period and post-flowering photoperiod responses in soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 123 421–429. 10.1007/s00122-011-1594-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cober E. R., Molnar S. J., Charette M., Voldeng H. D. (2010). A new locus for early maturity in soybean. Crop Sci. 50 524–527. 10.2135/cropsci2009.04.0174 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cober E. R., Tanner J. M., Voldeng H. D. (1996). Genetic control of photoperiod response in early-maturing, near-isogenic soybean lines. Crop Sci. 36 601–605. 10.2135/cropsci1996.0011183X003600030013x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doi K., Izawa T., Fuse T., Yamanouchi U., Kubo T., Shimatani Z., et al. (2004). Ehd1, a B-type response regulator in rice, confers short-day promotion of flowering and controls FT-like gene expression independently of Hd1. Genes Dev. 18 926–936. 10.1101/gad.1189604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle J. J., Doyle J. L. (1990). Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus 12 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fan C., Hu R., Zhang X., Wang X., Zhang W., Zhang Q., et al. (2014). Conserved CO-FT regulons contribute to the photoperiod flowering control in soybean. BMC Plant Biol. 14:9. 10.1186/1471-2229-14-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr W. R., Caviness C. E., Burmood D. T., Pennington J. S. (1971). Stage of development descriptions for soybeans, Glycine max (L.) merrill. Crop Sci. 11 929–931. 10.2135/cropsci1971.0011183X001100060051x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Funatsuki H., Kawaguchi K., Matsuba S., Sato Y., Ishimoto M. (2005). Mapping of QTL associated with chilling tolerance during reproductive growth in soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 111 851–861. 10.1007/s00122-005-0007-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izawa T., Oikawa T., Sugiyama N., Tanisaka T., Yano M., Shimamoto K. (2002). Phytochrome mediates the external light signal to repress FT orthologs in photoperiodic flowering of rice. Genes Dev. 16 2006–2020. 10.1101/gad.999202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia H., Jiang B., Wu C., Lu W., Hou W., Sun S., et al. (2014). Maturity group classification and maturity locus genotyping of early-maturing soybean varieties from high-latitude cold regions. PLoS One 9:e94139. 10.1371/journal.pone.0094139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang B., Nan H., Gao Y., Tang L., Yue Y., Lu S., et al. (2014). Allelic combinations of soybean maturity loci E1, E2, E3 and E4 result in diversity of maturity and adaptation to different latitudes. PLoS One 9:e106042. 10.1371/journal.pone.0106042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima S., Takahashi Y., Kobayashi Y., Monna L., Sasaki T., Araki T., et al. (2002). Hd3a, a rice ortholog of the Arabidopsis FT gene, promotes transition to flowering downstream of Hd1 under short-day conditions. Plant Cell Physiol. 43 1096–1105. 10.1093/pcp/pcf156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong F., Liu B., Xia Z., Sato S., Kim B. M., Watanabe S., et al. (2010). Two coordinately regulated homologs of FLOWERING LOCUS T are involved in the control of photoperiodic flowering in soybean. Plant Physiol. 154 1220–1231. 10.1104/pp.110.160796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong L., Lu S., Wang Y., Fang C., Wang F., Nan H., et al. (2018). Quantitative trait locus mapping of flowering time and maturity in soybean using next-generation sequencing-based analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 9:995. 10.3389/fpls.2018.00995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurasch A. K., Hahn V., Leiser W. L., Vollmann J., Schori A., Bétrix C. A., et al. (2017). Identification of mega-environments in Europe and effect of allelic variation at maturity E loci on adaptation of European soybean. Plant Cell Environ. 40 765–778. 10.1111/pce.12896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langewisch T., Zhang H., Vincent R., Joshi T., Xu D., Bilyeu K. (2014). Major soybean maturity gene haplotypes revealed by SNPViz analysis of 72 sequenced soybean genomes. PLoS One 9:e94150. 10.1371/journal.pone.0094150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Wang X., Song W., Huang X., Zhou J., Zeng H., et al. (2017). Genetic variation of maturity groups and four E genes in the Chinese soybean mini core collection. PLoS One 12:e0172106. 10.1371/journal.pone.0172106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Abe J. (2010). QTL mapping for photoperiod insensitivity of a Japanese soybean landrace Sakamotowase. J. Hered. 101 251–256. 10.1093/jhered/esp113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Fujita T., Yan Z. H., Sakamoto S., Xu D., Abe J. (2007). QTL mapping of domestication-related traits in soybean (Glycine max). Ann. Bot. 100 1027–1038. 10.1093/aob/mcm149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Kanazawa A., Matsumura H., Takahashi R., Harada K., Abe J. (2008). Genetic redundancy in soybean photoresponses associated with duplication of the phytochrome A gene. Genetics 180 995–1007. 10.1534/genetics.108.092742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Kim M. Y., Kang Y. J., Van K., Lee Y. H., Srinives P., et al. (2011). QTL identification of flowering time at three different latitudes reveals homeologous genomic regions that control flowering in soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 123 545–553. 10.1007/s00122-011-1606-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S., Li Y., Wang J., Srinives P., Nan H., Cao D., et al. (2015). QTL mapping for flowering time in different latitude in soybean. Euphytica 206 725–736. 10.1007/s10681-015-1501-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McBlain B. A., Hesketh J. D., Bernard R. L. (1987). Genetic effects on reproductive phenology in soybean isolines differing in maturity genes. Can. J. Plant Sci. 67 105–115. 10.4141/cjps87-012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto Y., Nonoue Y., Yano M., Izawa T. (2016). Hd1a, CONSTANS ortholog in rice, functions as an Ehd1 repressor through interaction with monocot-specific CCT-domain protein Ghd7. Plant J. 86 221–223. 10.1111/tpj.13168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saindon G., Voldeng H. D., Beversdorf W. D., Buzzell R. I. (1989). Genetic control of long daylength response in soybean. Crop Sci. 29 1436–1439. 10.2135/cropsci1989.0011183X002900060021x 11872321 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samanfar B., Molnar S. J., Charette M., Schoenrock A., Dehne F., Golshani A., et al. (2017). Mapping and identification of a potential candidate gene for a novel maturity locus, E10, in soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 130 377–390. 10.1007/s00122-016-2819-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmutz J., Cannon S. B., Schlueter J., Ma J., Mitros T., Nelson W., et al. (2010). Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature 463 178–183. 10.1038/nature08670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severin A. J., Woody J. L., Bolon Y. T., Joseph B., Diers B. W., Farmer A. D., et al. (2010). RNA-seq atlas of Glycine max: a guide to the soybean transcriptome. BMC Plant Biol. 10:160. 10.1186/1471-2229-10-160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Q., Jia G., Zhu Y., Grant D., Nelson R. T., Hwang E. Y., et al. (2010). Abundance of SSR motifs and development of candidate polymorphic SSR markers (BARCSOYSSR_1.0) in soybean. Crop Sci. 50 1950–1960. 10.2135/cropsci2009.10.0607 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song Q., Marek L. F., Shoemaker R. C., Lark K. G., Concibido V. C., Delannay X., et al. (2004). A new integrated genetic linkage map of the soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 109 122–128. 10.1007/s00122-004-1602-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Ito S., Imaizumi T. (2013). Flowering time regulation: photoperiod- and temperature-sensing in leaves. Trends Plant Sci. 18 575–583. 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshima R., Hayashi T., Zhu J., Zhao C., Xu M., Yamaguchi N., et al. (2016). A soybean quantitative trait locus that promotes flowering under long days is identified as FT5a, a FLOWERING LOCUS T ortholog. J. Exp. Bot. 67 5247–5258. 10.1093/jxb/erw283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaki S., Matsuo S., Wong H. L., Yokoi S., Shimamoto K. (2007). Hd3a protein is a mobile flowering signal in rice. Science 316 1033–1036. 10.1126/science.1141753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubokura Y., Matsumura H., Xu M., Liu B., Nakshima H., Anai T., et al. (2013). Genetic variation in soybean at the maturity locus E4 is involved in adaptation to long days at high latitudes. Agronomy 3 117–134. 10.3390/agronomy3010117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubokura Y., Watanabe S., Xia Z., Kanamori H., Yamagata H., Kaga A., et al. (2014). Natural variation in the genes responsible for maturity loci E1, E2, E3 and E4 in soybean. Ann. Bot. 113 429–441. 10.1093/aob/mct269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay A. P., Ellis R. H., Summerfield R. J., Roberts E. H., Qi A. (1994). Characterization of photothermal flowering responses in maturity isolines of soyabean [Glycine max (L.) Merrill] cv. Clark. Ann. Bot. 74 87–96. 10.1093/aob/74.1.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Graef G. L., Procopiuk A. M., Diers B. W. (2004). Identification of putative QTL that underlie yield in interspecific soybean backcross populations. Theor. Appl. Genet. 108 458–467. 10.1007/s00122-003-1449-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S., Harada K., Abe J. (2012). Genetic and molecular bases of photoperiod responses of flowering in soybean. Breed. Sci. 61 531–543. 10.1270/jsbbs.61.531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S., Hideshima R., Xia Z., Tsubokura Y., Sato S., Nakamoto Y., et al. (2009). Map-based cloning of the gene associated with the soybean maturity locus E3. Genetics 182 1251–1262. 10.1534/genetics.108.098772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S., Tsukamoto C., Oshita T., Yamada T., Anai T., Kaga A. (2017). Identification of quantitative trait loci for flowering time by a combination of restriction site-associated DNA sequencing and bulked segregant analysis in soybean. Breed. Sci. 67 277–285. 10.1270/jsbbs.17013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S., Xia Z., Hideshima R., Tsubokura Y., Sato S., Yamanaka N., et al. (2011). A map-based cloning strategy employing a residual heterozygous line reveals that the GIGANTEA gene is involved in soybean maturity and flowering. Genetics 188 395–407. 10.1534/genetics.110.125062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Price B. W., Haider W., Seufferheld G., Nelson R., Hanzawa Y. (2014). Functional and evolutionary characterization of the CONSTANS gene family in short–day photoperiodic flowering in soybean. PLoS One 9:e85754. 10.1371/journal.pone.0085754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Z., Watanabe S., Yamada T., Tsubokura Y., Nakashima H., Zhai H., et al. (2012). Positional cloning and characterization reveal the molecular basis for soybean maturity locus E1 that regulates photoperiodic flowering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 E2155–E2164. 10.1073/pnas.1117982109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M., Xu Z., Liu B., Kong F., Tsubokura Y., Watanabe S., et al. (2013). Genetic variation in four maturity genes affects photoperiod insensitivity and PHYA-regulated post-flowering responses of soybean. BMC Plant Biol. 13:91. 10.1186/1471-2229-13-91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M., Yamagishi N., Zhao C., Takeshima R., Kasai M., Watanabe S., et al. (2015). The soybean-specific maturity gene E1 family of floral repressors controls night-break responses through down-regulation of FLOWERING LOCUS T orthologs. Plant Physiol. 168 1735–1746. 10.1104/pp.15.00763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue W., Xing Y., Weng X., Zhao Y., Tang W., Wang L., et al. (2008). Natural variation in Ghd7 is an important regulator of heading date and yield potential in rice. Nat. Genet. 40 761–767. 10.1038/ng.143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T., Hajika M., Yamada N., Hirata K., Okabe A., Oki N., et al. (2012). Effects on flowering and seed yield of dominant alleles at maturity loci E2 and E3 in a Japanese cultivar, Enrei. Breed. Sci. 61 653–660. 10.1270/jsbbs.61.653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka N., Nagamura Y., Tsubokura Y., Yamamoto K., Takahashi R., Kouchi H., et al. (2000). Quantitative trait locus analysis of flowering time in soybean using a RFLP linkage map. Breed. Sci. 50 109–115. 10.1270/jsbbs.50.109 11347903 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yano M., Katayose Y., Ashikari M., Yamanouchi U., Monna L., Fuse T., et al. (2000). Hd1, a major photoperiod sensitivity quantitative trait locus in rice, is closely related to the Arabidopsis flowering time gene CONSTANS. Plant Cell 12 2473–2483. 10.1105/tpc.12.12.2473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai H., Lü S., Wang Y., Chen X., Ren H., Yang J., et al. (2014). Allelic variations at four major maturity E genes and transcriptional abundance of the E1 gene are associated with flowering time and maturity of soybean cultivars. PLoS One 9:e97636. 10.1371/journal.pone.0097636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai H., Lü S., Wu H., Zhang Y., Zhang X., Yang J. (2015). Diurnal expression pattern, allelic variation, and association analysis reveal functional features of the E1 gene in control of photoperiodic flowering in soybean. PLoS One 10:e0135909. 10.1371/journal.pone.0135909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Wang Y., Luo G., Zhang J., He C., Wu X., et al. (2004). QTL mapping of ten agronomic traits on the soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) genetic map and their association with EST markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 108 1131–1139. 10.1007/s00122-003-1527-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.