Abstract

Sulfonamide is present in many important drugs, due to its unique chemical and biological properties. In contrast, naturally occurring sulfonamides are rare, and their biosynthetic knowledge are scarce. Here we identify the biosynthetic gene cluster of sulfonamide antibiotics, altemicidin, SB-203207, and SB-203208, from Streptomyces sp. NCIMB40513. The heterologous gene expression and biochemical analyses reveal unique aminoacyl transfer reactions, including the tRNA synthetase-like enzyme SbzA-catalyzed L-isoleucine transfer and the GNAT enzyme SbzC-catalyzed β-methylphenylalanine transfer. Furthermore, we elucidate the biogenesis of 2-sulfamoylacetic acid from L-cysteine, by the collaboration of the cupin dioxygenase SbzM and the aldehyde dehydrogenase SbzJ. Remarkably, SbzM catalyzes the two-step oxidation and decarboxylation of L-cysteine, and the subsequent intramolecular amino group rearrangement leads to N-S bond formation. This detailed analysis of the aminoacyl sulfonamide antibiotics biosynthetic machineries paves the way toward investigations of sulfonamide biosynthesis and its engineering.

Sulfonamide is in many important drugs yet is rare in nature and little is known about the synthesis of sulfonamide containing antibiotics. Here, the authors report on a detailed analysis of the biosynthesis machineries of the aminoacyl sulfonamide antibiotics.

Introduction

Actinomycetical alkaloids exhibit remarkable structural diversity, as represented by peptide, aminobenzoate, oxazole, thiazole, and indolocarbazole-derived secondary metabolites1–5. Their biosynthetic pathways are rich in rare enzymes, including those that catalyze heteroatom–heteroatom (X–X) bond-forming reactions, thereby appending important biological functions to the molecules6. While several enzymes involved in the N–N bond formation have been identified recently; e.g., CreDEM in cremeomycin biosynthesis7,8, KtzIT in piperazate biosynthesis9, and Spb38 and 40 in s56-p1 biosynthesis10, only two examples have been reported for N–S bond formation. Thus, the FAD-dependent monooxygenase XiaH catalyzes the radical-mediated N–S bond-forming reaction in the biosynthesis of sulfadixiamycins A11, and the putative aminotransferase AcmN was proposed to be involved in the N–S bond formation in 2-deschloro-dealanylascamycin biosynthesis12. Considering the presence of hundreds of N–S bond containing alkaloids in nature5, many unusual enzyme reactions remain unexplored for the N–S bond-forming chemistries.

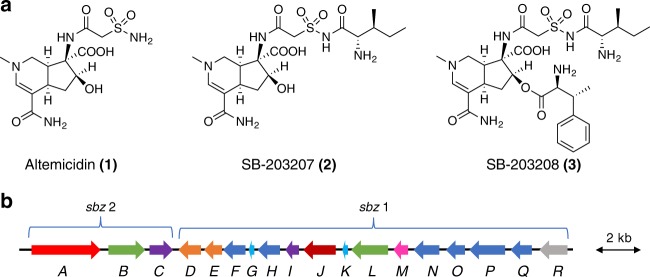

The sulfonamide functional group exhibits less basicity and more rigid structural properties, as compared with carboxamide, and thereby contributes to biological activities such as sweeteners, and drugs functioning as diuretics, uricosurics, hypoglycemic treatments, antimicrobial agents, and herbicides13. This functional group is widely used in medicinal chemistry through the coupling methodology of sulfonyl chloride and amide, whereas its biosynthesis still remains to be rigorously investigated. For example, altemicidin (1), consisting of sulfonamide and 6-azatetrahydroindane moieties, was first isolated from Streptomyces sioyaensis SA-1758 as an insecticidal and acaricidal antibiotic14,15. In contrast, its aminoacylated derivatives, SB-203207 (2) and SB-203208 (3), were isolated from Streptomyces sp. NCIMB 40513 as isoleucyl tRNA synthetase inhibitors16,17 (Fig. 1a). Their unique chemical structures and biological activities have attracted the interest of synthetic chemists, leading to the recent total syntheses of 1 and 218–20. In contrast, since no biosynthetic studies have been reported, we conducted investigations of the biogenesis of 1–3 in Streptomyces sp. NCIMB 40513.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of the aminoacyl sulfonamide antibiotics and the gene organization of sbz cluster. a Structures of the aminoacyl sulfonamide antibiotics and b the organization of the sbz cluster (Please see Supplementary Table 1 for more details.)

Here, we report the identification of the biosynthetic gene cluster of 1–3, and its successful heterologous expression in the Streptomyces lividans host. Furthermore, biochemical analyses disclose three aminoacyl transfer reactions and the biogenesis of sulfonamide through N–S bond formation. Thus, we elucidate the three aminoacyl transfer reactions, including the tRNA synthetase-like enzyme SbzA-catalyzed installation of L-isoleucine onto 1 to afford 2, and the biogenesis of a sulfonamide from L-cysteine by the cupin dioxygenase SbzM. These unusual biosynthetic machineries lead to the construction of the rare aminoacyl sulfonamide molecular scaffold.

Results

Identification of the biosynthetic gene cluster

First, we sought to identify the biosynthetic gene cluster of SB-203208 (3), an Ile-tRNA synthetase inhibitor, with one sulfonamide, two carboxamides, one ester, L-isoleucine, and β-methylphenylalanine partial structures (Fig. 1a), from the genome sequence of Streptomyces sp. NCIMB 40513. Since the resistance gene for a specific antibiotic is often clustered with its biosynthetic genes, we focused on the Ile-tRNA synthetase genes in the genome. As a result, a BLASTp search using Escherichia coli Ile-tRNA synthetase (accession number P00956.5) as the query revealed two Ile-tRNA synthetase genes, Ssp-IleRS (27% amino acid identity) and sbzA (25% identity). Interestingly, sbzA is located in a 20-kb gene cluster (sbz cluster) encoding 18 genes, including those of two adenylate-forming enzymes (sbzB and sbzL) and two acyl carrier proteins (sbzG and sbzK), which are thought to be involved in amide bond-forming reactions21 (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 1). In addition, the sbz cluster includes one gene (sbzD) that exhibits 40% identity to MppJ, a methyltransferase that produces β-methylphenylalanine in mannopeptimycin biosynthesis22. Based on these observations, we assigned the sbz cluster as a candidate biosynthetic gene cluster of 1–3. Interestingly, the sbz cluster consists of two operons, sbz2 (sbzA-C) and sbz1 (sbzD-R), and thus it is suitable for heterologous expression since only two promoters are sufficient for the expression of all of the genes.

Heterologous expression of the sbz cluster

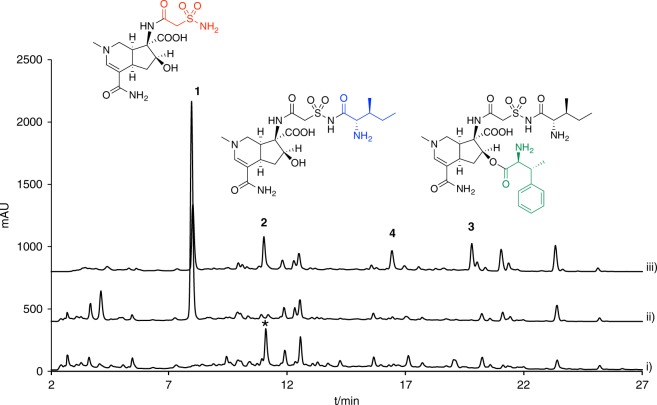

We cloned the sbz1 and sbz2 operons under the control of the ermE promoter on two phage-integration vectors, and introduced them into the Streptomyces lividans TK21 strain (Supplementary Data set 1). First, we analyzed the water extract of the S. lividans culture expressing sbz1 by HPLC, and found one peak at Rt = 8.0 min that was not present in the negative control (Fig. 2). The product 1 (10 mg/L) was thus purified from the large-scale culture. By comparing its NMR and HR-MS data with those in the literature18, we identified the product as altemicidin (1) (Supplementary Figs. 1–3). Next, we examined the extract from S. lividans expressing both the sbz1 and sbz2 operons, and detected 2 (1.1 mg/L) and 3 (1.8 mg/L) as their products (Fig. 2). Comparisons of the NMR data unambiguously established that they are identical to SB-203207 (2) and SB-203208 (3), respectively17 (Supplementary Figs. 4–8). The compound 4 whose m/z was consistent with β-methylphenyalanyl-1 was also detected as a product (Supplementary Fig. 1). In addition, we analyzed the β-methylphenylalanine hydrolyzed from 3 by chiral HPLC, and confirmed its stereochemistry as 2S, 3R23 (Supplementary Fig. 9). These data clearly demonstrated that 1 was produced by the enzymes encoded in the sbz1 operon, and the enzymes encoded in the sbz2 operon were required for the installation of L-isoleucine and β-methylphenylalanine onto 1, to yield 2 and 3.

Fig. 2.

HPLC analysis (monitored at 300 nm) of the water extracts from the S. lividans strain expressing sbz gene cluster. The HPLC traces of the extracts from i) S. lividans TK21, ii) S. lividans TK21/sbz1, and iii) S. lividans TK21/sbz1&2. * indicates the compound with 275 nm UV max which is not relevant to 1–4

Enzymes involved in aminoacyl transfer reactions

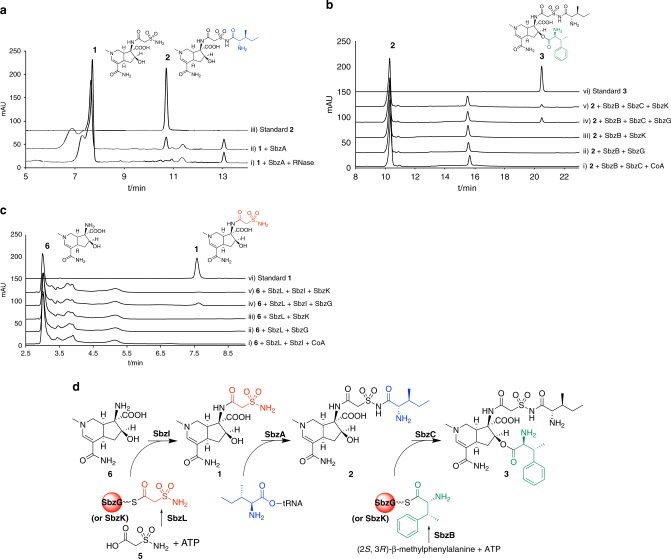

To understand the functions of the three enzymes encoded in the sbz2 operon, the purified His-tagged recombinant proteins of SbzA (Ile-tRNA synthetase-like enzyme), SbzB (adenylate-forming enzyme), and SbzC (GNAT family enzyme) (Supplementary Fig. 10, Supplementary Table 1) were subjected to in vitro enzyme reactions. The results demonstrated that SbzA efficiently catalyzes the N-aminoacyl transfer reaction of L-isoleucine onto the primary sulfonamide of 1 to yield 2, in the presence of Ile-tRNAE.coliIle, which was supplied by an in vitro translation kit based on an E. coli lysate (Fig. 3a, d). The addition of RNase to the reaction mixture completely abolished the production of 2 (Fig. 3a), and thus it suggested that Ile-tRNA is essential for the SbzA enzyme reaction. We also conducted the SbzA enzyme reaction with 1 and Ile-tRNASspIle, which was synthesized by Ssp-IleRS from bulk tRNA isolated from Streptomyces sp. NCIMB40513, and detected 2 as a product (Supplementary Fig. 11). This result clearly reconfirmed the dependency of SbzA reaction on Ile-tRNA. Interestingly, SbzA alone can also produce a trace amount of 2 in the absence of Ssp-IleRS, even though the yield is 94% less than SbzA + Ssp_IleRS reaction. These data suggested that SbzA can also catalyze the isoleucyl transfer reaction onto tRNAIle, but with much less efficiency than that of Ssp_IleRS.

Fig. 3.

HPLC analysis (monitored at 300 nm) of the in vitro aminoacyl transfer enzyme reactions. a The assay of SbzA with altemicidin (1) and Ile-tRNA as substrates; (i) SbzA + RNase, (ii) SbzA, and (iii) the authentic standard of SB-203207 (2). b The assay of SbzBCG (or BCK) with 2 and β-methylphenylalanine as substrates; (i) SbzB + SbzC + CoA, (ii) SbzB + SbzG, (iii) SbzB + SbzK, (iv) SbzB + SbzC + SbzG, (v) SbzB + SbzC + SbzK, and (vi) the authentic standard of SB-203208 (3). c The assay of SbzILG (or ILK) with 6; (i) SbzL + SbzI + CoA, (ii) SbzL + SbzG, (iii) SbzL + SbzK, (iv) SbzL + SbzI + SbzG, (v) SbzL + SbzI + SbzK, and (vi) the authentic standard of 1. d Proposed mechanisms of the aminoacyl transfer enzyme reactions by SbzABCGIL (or SbzABCILK)

We then investigated the enzymes involved in the O-acyltransfer of β-methylphenylalanine onto 2 to yield the final product 3 (Fig. 3d). We thus tested the adenylate-forming enzyme SbzB with various amino acids, including β-methylphenylalanine, as substrates24. As a result, SbzB indeed selectively adenylated (2S, 3R)-β-methylphenylalanine as the best substrate (Supplementary Fig. 12), whereas other stereoisomers of β-methylphenylalanine were not accepted for the enzyme reaction (Supplementary Fig. 9). Since the candidate acyltransferase SbzC (GNAT family enzyme) shares similarity with mycothiol acetyltransferase, which accepts acetyl-CoA25, we incubated SbzB and SbzC with 2, ATP, and CoA, anticipating that the CoA thioester of β-methylphenylalanine thus formed may serve as a substrate for the SbzC-catalyzed acyltransfer reaction. However, the reaction did not yield the expected product 3 (Fig. 3b), suggesting that the adenylate-forming enzyme SbzB utilizes an acyl carrier protein to load β-methylphenylalanine, as in the case of the NRPS system. Indeed, when we added an acyl carrier protein, SbzG or SbzK, encoded in the sbz1 operon (Supplementary Table 1), to the assay mixture, the enzyme reaction afforded the β-methylphenylalanine-loaded SbzG or SbzK carrier protein, as confirmed by an LC-ESI-MS analysis (Supplementary Fig. 13). Interestingly, SbzB accepted both SbzG and SbzK with almost the same preference in vitro, and the subsequent O-acyltransfer reaction by SbzC successfully yielded the small amount of final product 3 (Fig. 3b, d). We also tested 1 as an acceptor substrate for SbzBCG reaction, to detect 4 as a product, but with much less efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 14).

Finally, the second adenylate-forming enzyme SbzL, encoded in the sbz1 operon (Supplementary Table 1), was shown to be responsible for the N-acyltransfer of 2-sulfamoylacetic acid (5) onto 6 to yield altemicidin (1) (Fig. 3d). SbzL thus selectively accepts 5 as a substrate, while the other tested amino acids, including L-cysteine, L-cysteic acid, and L-cysteine sulfinic acid, were not the substrates of SbzL (Supplementary Fig. 12). As in the case of SbzB, SbzL also accepted both SbzG and SbzK as acyl carrier proteins (Supplementary Fig. 13). Furthermore, in vitro analyses clearly established that the second GNAT N-acyltransferase, SbzI, installs 2-sulfamoylacetate from the carrier protein onto the amino group of 6 to yield 1 (Fig. 3c, d). This suggested that the sulfonamide 5 is biosynthesized before it is loaded onto the acyl carrier protein. Notably, most of the GNAT family acyltransferases accept CoA-linked substrates26, but some known exceptions include the N-acyl amino acid synthase FeeM, which uptakes its substrates from the acylated carrier protein prepared by adenylate-forming enzymes27. This would probably increase the specificity of substrate recognition, as in the cases of SbzC and SbzI.

Enzymes involved in biogenesis of sulfonamide

To elucidate the biosynthesis of sulfonamide and the N–S bond-forming reaction, we tested the gene deletions of sbzF, H, J, and M–Q (Supplementary Table 1). As a result, all of the mutant strains no longer produced 1 (Supplementary Fig. 15a), indicating that all of the tested genes are essential for the production of 1. The mutants were further analyzed for their metabolites by Hilic–LC–MS. While the ΔsbzF, H, and N–Q mutants still yielded 5, ΔsbzM and ΔsbzJ no longer produced it (Supplementary Fig. 15b). In addition, when 5 was supplemented into the ΔsbzJ and ΔsbzM culture media, both of the mutants resumed the production of 1 (Supplementary Fig. 15c). These results confirmed that SbzM (cupin dioxygenase) and SbzJ (aldehyde dehydrogenase) (Supplementary Table 1) are essential for the biogenesis of the sulfonamide 5.

We then performed feeding experiments by supplying [13C3, 15N1]-L-cysteine to the culture medium, and analyzed the NMR spectra of 1. As a result, the 13C NMR signals at C-12 and C-13 and the 15N NMR signal (δ 89.5), corresponding to the primary amine, were significantly enhanced (Supplementary Fig. 16a–c), which clearly supported the incorporation of cysteine into sulfonamide. Interestingly, the m/z values of 1 and 5 from the fed culture were 3 Da larger than the original one (Supplementary Fig. 16d, e). This indicated that the 15N atom of the labeled cysteine was retained in the sulfonamide, as were the two 13C atoms after the decarboxylation reaction. Based on these observations, we propose that L-cysteine undergoes the sequential oxidation of the sulfur atom and the decarboxylation. The subsequent intramolecular rearrangement of the amino group onto the oxidized sulfur atom leads to the S–N bond formation, during the enzyme reactions catalyzed by SbzM (cupin dioxygenase) and SbzJ (aldehyde dehydrogenase) (Fig. 4d).

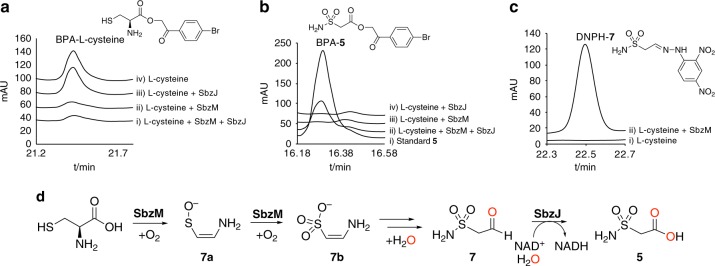

Fig. 4.

HPLC analysis of the products of SbzM and SbzJ reactions. The substrate L-cysteine was derivatized with 4-bromophenacyl (4-BPA) bromide. a (i) SbzM+SbzJ, (ii) SbzM, (iii) SbzJ, and (iv) no enzyme, and the reaction products were derivatized with 4-BPA. b (i) Standard 5, (ii) SbzM + SbzJ, (iii) SbzM, and (iv) SbzJ, or 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) hydrochloride. c (i) No enzyme and (ii) SbzM. The chromatogram represents the UV absorbance at 254 nm. d It was demonstrated that L-cysteine is converted into 2-sulfamoylacetic acid (5) by the collaboration of SbzM and SbzJ. In contrast, the cupin dioxygenase SbzM produces 2-sulfamoylacetic aldehyde (7) from L-cysteine via (Z)-(2-aminovinyl)sulfanolate (7a) and (Z)-2-aminoethanone-1-sulfonate (7b). The oxygens derived from water are colored red

To further clarify the biosynthesis of sulfonamide, we performed in vitro enzyme reactions of SbzJ and SbzM with L-cysteine as the substrate. To monitor the enzyme reaction, the carboxyl groups were derivatized with 4-bromophenacyl (4-BPA) bromide, and the results clearly demonstrated that L-cysteine is efficiently converted into the sulfonamide 5 by the collaboration of SbzM and SbzJ (Fig. 4a, b). Next, we analyzed the cupin dioxygenase SbzM enzyme reaction product, 2-sulfamoylacetic aldehyde (7), by 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) hydrochloride derivatization (Fig. 4c) (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 17–21, Supplementary Table 2). To unambiguously determine the product, the SbzM enzyme reaction was performed in an NMR tube with 13C-enriched [13C3, 15N1]-L-cysteine as the substrate, and analyzed by 13C NMR, DEPT135, and HMQC spectroscopy. The analyses detected a single product that possessed one methylene (δ1H 3.40, δ13C 60.2 (d, J = 179.5 Hz)) and one methine (δ1H 5.34, δ13C 86.4 (d, J = 179.5 Hz)), and its m/z was 140.0022 (Cal. 140.0023, C2H6NO4S−) (Supplementary Figs. 22–25). These data indicated that the detected product was a geminal diol28, which is the hydrate form of the sulfonamide aldehyde 7.

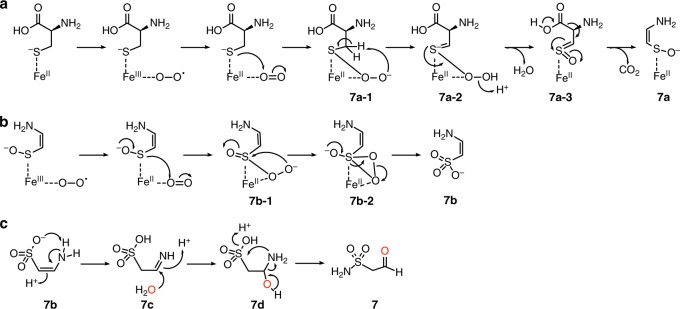

Taken together, for the biosynthesis of the sulfonamide 5, we propose that the cupin dioxygenase SbzM catalyzes the decarboxylation coupled with monooxygenation to yield (Z)-(2-aminovinyl)sulfanolate 7a and dioxygenation of L-cysteine to yield the reactive sulfonate–enamine 7b. The subsequent N–S bond-forming intramolecular rearrangement of the amino group, and the oxidation of the resulting sulfonamide aldehyde 7 by the aldehyde dehydrogenase SbzJ, finally generate 5 (Fig. 4d). Based on the annotation of the aldehyde dehydrogenase SbzJ and the fact that we could not detect any additional intermediates from the SbzJ/SbzM enzyme reaction in the absence of NAD+ (Supplementary Fig. 26), we concluded that SbzJ catalyzes only the dehydrogenation of the aldehyde 7 to yield 5. The structure of 7b was determined as (Z)-2-aminoethanone-1-sulfonate, from the structure of the dansylated-7b (Supplementary Figs. 1, 27–30, Supplementary Table 3).

When L-cysteine was incubated with SbzM and SbzJ in the presence of H218O, the m/z of 5 increased by 4 Da (Supplementary Fig. 31), indicating that the second H218O molecule was incorporated in addition to the one incorporated in the SbzJ aldehyde dehydrogenase reaction. Furthermore, the LC–MS analysis of the SbzM enzyme reaction product with m/z = 121.9912, corresponding to the aldehyde 7, was 18O-labeled when we employed H218O as the solvent (Supplementary Fig. 32). These data clearly suggested that 7 was generated through the hydrolysis of 7b (Figs. 4d, 5c).

Fig. 5.

The proposed reaction mechanism of SbzM. a L-cysteine is transformed into (Z)-(2-aminovinyl)sulfanolate (7a) via the decarboxylation coupled with sulfur monooxygenation. b 7a is dioxygenated into (Z)-2-aminoethanone-1-sulfonate (7b). 7b was tautomerized into 7c, the hydration of the imine of 7c, and the hydrolyzed amine in 7d attacks the protonated sulfonate to yield 7 with the release of water. The Fe can be substituted with Ni. The oxygens derived from water are colored red

Finally, since the presence of a metal ion is reported to be crucial for the cupin enzyme activity, we examined the metal ion dependency of the SbzM enzyme reaction by the metal chelation and restoration method28. Thus, after an incubation with EDTA, various metal ions (Fe2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Mn2+, Ni2+, and Co2+) were added and the enzyme activities were evaluated. As a result, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Fe2+ restored the activity to 52, 45, and 40%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 33). Furthermore, we confirmed that the contents of Ni2+ and Fe2+ increased while no increase for other metal ions in each of the enzymes by ICP-MS analyses. Therefore, we concluded that Fe2+ and Ni2+ bind to the enzyme and are essential for the SbzM enzyme reaction. On the other hand, the enzyme incubated with Cu2+ precipitated after the successive dialysis to reduce the concentration of metal to significantly lower than the enzyme concentration. Notably, the preference for the Ni ion is rare for the cupin enzymes, but was also reported for the dimethylsulfoniopropionate lyase DddK29,30 and Streptomyces quercetinase QueD31,32. The KM and kcat/KM values for L-cysteine were 0.53 ± 0.08 mM and 1.67 × 103 min−1mM−1 (n = 2) (Supplementary Fig. 33), respectively, which are comparable with those of other cupin family enzymes29.

Discussion

In this study, we identified the biosynthetic gene cluster of the antibiotics with rare sulfonamide and 6-azatetrahydroindane scaffolds, altemicidin (1), SB-203207 (2), and SB-203208 (3), from Streptomyces sp. NCIMB40513, and succeeded in heterologous gene expression in S. lividans TK21. Furthermore, in vitro biochemical analyses revealed three unique aminoacyl transfer enzyme reactions, including that of the GNAT family enzyme SbzI-catalyzed installation of 2-sulfamoylacetic acid (5) onto the 6-azatetrahydroindane precursor to yield 1, the tRNA synthetase-like enzyme SbzA-catalyzed L-isoleucine transfer to yield 2, and the second GNAT enzyme SbzC-catalyzed β-methylphenylalanine transfer to yield the final product 3 (Fig. 3d). Moreover, we elucidated the N–S bond-forming reaction in the biogenesis of the sulfonamide 5 from L-cysteine, by collaboration of the cupin dioxygenase SbzM and the aldehyde dehydrogenase SbzJ (Fig. 4d). These unusual biosynthetic machineries successfully led to the construction of the rare aminoacyl sulfonamide molecular scaffold.

Remarkably, SbzA is a tRNA synthetase-like enzyme that catalyzes aminoacyl transfer from the corresponding aminoacyl-tRNA (aa-tRNA) to a non-peptide secondary metabolite. A homology model of SbzA constructed with Swiss-Prot, using Ile-tRNA synthetase from Thermus thermophilus33,34 (1JZQ, 37.6% identity) as the template, showed that it belongs to the class Ia aa-tRNA synthetases, which consist of multiple domains, including the Rossmann fold, editing, and zinc-binding domains (Supplementary Fig. 34)33–35. The in vitro assay of SbzA with bulk tRNA showed that Ssp_IleRS aminoacylates tRNAIle, and then, SbzA installs isoleucyl moiety on 1. Thus, we concluded that Ssp_IleRS catalyzes the tRNA aminoacylation, and SbzA in the gene cluster catalyzes the aminoacyl transfer from Ile-tRNA onto 1 to yield 2. Interestingly, SbzA can also catalyze aminoacylation of tRNAIle, but with much less efficiency than that of Ssp_IleRS. Notably, SbzA possesses conserved “HIGH” and “KMSKS" sequences that are signature ATP-binding motifs in the Rossmann fold of class I aaRS35, even though there are slight modifications (Supplementary Fig. 34), which could support the observation that SbzA also catalyzes the tRNA acylation. The detailed structure–function relationship on SbzA should be the subject of our future study. The aminoacyl moieties introduced by the known aa-tRNA-dependent transferases in secondary metabolism are Ser, Leu, Gly, Ala, Phe, Tyr, and Trp, and this is a report of the installation of Ile by a tRNA-dependent aminoacyl transferase36.

In the biogenesis of a sulfonamide, we proposed that the cupin dioxygenase SbzM catalyzes the sequential two-step oxidations of L-cysteine to yield the reactive (Z)-2-aminoethanone-1-sulfonate (7b) via (Z)-(2-aminovinyl)sulfanolate (7a), and the subsequent intramolecular rearrangement of the amino group onto the sulfur atom (N–S bond formation) generates the sulfonamide aldehyde 7 (Fig. 4d).

The reaction from L-cysteine to 7a was hypothesized as below (Fig. 5a). The cysteine binding to the enzyme changes the coordination of the iron, followed by the binding of the molecular oxygen to the ferrous ion and successive nucleophilic addition to yield 7a–1, in a similar manner to cysteine dioxygenase37. The resultant oxide anion abstracts the Cβ proton and the carbon–sulfur double bond is newly formed in 7a–2. This Cβ proton might be supported through ionic interaction with the amino acid residues in SbzM as seen in EpiD, a flavin-dependent cysteine decarboxylase38. An evolving negative charge on sulfur moves to oxygen, resulting in 7a–3 sulfene structure, which is generated through elimination of HCl from sulfinyl chloride in chemical synthesis39. Finally, this intermediate generates a more stable ene-thioaldehyde S-oxide40 7a.

The oxidation mechanism of 7a to 7b is predicted to resemble that proposed based on the the X-ray structure of the cupin-type cysteine dioxygenase complexed with cysteine persulfenate37 (Fig. 5b). The ferrous-bound molecular oxygen is attacked by the electron from the sulfanolate in nucleophilic addition mechanism to give 7b–1. The addition of the negatively charged distal oxygen to the sulfoxide generates thiadioxirane 7b–2. The migration of the lone pair on the sulfur driven by the electron migration from the sulfanolate and the cleavage of the O–O bond yield 7b. However, we cannot exclude the possibility of the S–O bond formation through radical mechanism in this step, as discussed in the literature37. Finally, 7b tautomerizes to 7c, the resultant imine of 7c is hydrolyzed, and the hydrolyzed amine in 7d attacks the protonated sulfonic acid, resulting in 7 accompanied with elimination of water as a leaving group (Fig. 5c).

The multistep reaction from L-cysteine to 7 triggered by SbzM is intriguing, as such a cascade reaction initiated by a cupin oxidase has rarely been reported, except for the one catalyzed by the recently reported fungal cupin enzyme in phenalenone biosynthesis41. The cupin enzyme that oxidizes the sulfur of cysteine42 and the one that abstracts the methylene proton at the α-position of dimethylsulfoniopropionate29,30 were known; however, SbzM is a cupin-type cysteine decarboxylase. Oxalate decarboxylase is a cupin-type decarboxylase43, but its reaction mechanism is likely to be different from the one that we proposed. The structural studies on SbzM are now in progress to further clarify its reaction mechanism.

It should be noted that the BLASTp search in JGI (https://img.jgi.doe.gov/) and NCBI (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) indicated that there are four paralog gene clusters in Streptomyces melanosporofaciens DSM 40318, Streptomyces sp. NRRL S-1868, Streptomyces antioxidans MUSC 164, and Streptomyces sp. NRRL F-5053 (Supplementary Fig. 35). In addition, homologs of the cupin dioxygenase SbzM are encoded in the genomes of several bacteria, and interestingly, some of them are clustered with secondary metabolism-like genes (Supplementary Figs. 35 and 36), suggesting the distribution of the SbzM-catalyzed cysteine metabolism that generates the reactive sulfonate–enamine compounds.

In conclusion, this study identified the biosynthetic gene cluster for the class of alkaloids with a 6-azatetrahydroindane and sulfonamide structure, and illuminated the biosynthetic machineries for the biogenesis of sulfonamide antibiotics. Importantly, the cupin dioxygenase SbzM catalyzes the cysteine-processing reactions to generate a sulfonamide, which is further modified by successive and unusual aminoacyl transfers. This knowledge will pave the way toward investigations of sulfonamide biosynthesis, as well as its engineering, to produce biologically active, unnatural sulfonamide antibiotics.

Methods

General experimental procedures

Solvents and chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Wako Chemicals Ltd., or Kanto Chemical Co., Inc., unless noted otherwise. Oligonucleotide primers were purchased from Eurofins Genetics or Sigma-Aldrich. PCR was performed using a TaKaRa PCR Thermal Cycler Dice® Gradient (TaKaRa), with Prime STAR Max DNA Polymerase (TaKaRa). Sequence analyses were performed by Eurofins Genetics. HPLC analysis was performed on a Shimadzu Prominence HPLC system with a Separar C18G column (4.6 mm I.D. × 250 mm, Rikaken Co. Ltd., Nagoya, Japan). The LC–MS analysis was performed on a Bruker Compact qTOF mass spectrometer with a Shimadzu Prominence HPLC system, using a COSMOSIL 5C18-AR-II column (2.0 mm I.D. × 150 mm, Nacalai Tesque, Inc., Kyoto, Japan). NMR spectra were obtained with JEOL ECX-500 or ECZ-500 spectrometers. Streptomyces sp. NCIMB 40513 was purchased from NCIMB, with the permit from GSK, Inc.

Genome sequencing

The sequencing was performed with an Ion PGM sequencer (Life Technologies), with a total number of 2,953,291 sequence reads (~300 bp). These sequences were assembled using the de novo assembler MIRA (v3.4.2.0). Further assembly to produce larger contigs was achieved with the Geneious assembler (Biomatters), with the default medium sensitivity. The putative protein-coding sequences (CDSs) were determined by a combination of 2ndFind (http://biosyn.nih.go.jp/2ndfind/).

Heterologous expression in Streptomyces lividans TK21

The proposed gene cluster was divided into two parts, sbzD-R as sbz 1 and sbzA-C as sbz 2. The sbz 1 part was amplified from the genome of Streptomyces sp. NCIMB 40513 with the primers I-VI (Supplementary Data set 1) into three fragments, and inserted into the EcoRI and HindIII sites of the pUC19 vector by in-fusion cloning. The fragment comprising ϕBT1, the aac(3)IV apramycin resistance gene, and the ermE promotor was amplified with the primers VII-VIII and inserted into the pUC19-sbz 1 vector by λ RED-mediated recombination with the pKD78 vector. The resultant vector was renamed pZH1-sbz1. The sbz 2 part was amplified with the primers IX-X and inserted into the pUC19 vector, along with ϕC31, the tsr thiostrepton resistance gene, and the ermE promotor, by in-fusion cloning. The resultant vector was renamed pZH2-sbz2.

Transformation of the vectors was performed by the general protoplast-PEG mediated transformation for S. lividans TK21. The resultant strains were named S. lividans/sbz 1 and S. lividans/sbz 1 and 2.

Analysis of metabolites

Fermentation of the heterologous expression strains was performed in 500 mL-baffled flasks containing 100 mL A3M medium, consisting of 2.0% starch, 2.0% glycerol, 0.5% glucose, 1.5% Pharma media (Archer Daniels Midland Co.), 1.0% HP-20 (Nihon Rensui), and 0.3% yeast extract (pH 7.0), for 6 days at 30 °C and 160 min−1. The culture broth was centrifuged and analyzed directly. The HPLC solvent system was H2O containing 50 mM NH4OAc (solvent A) and CH3OH (solvent B), with a gradient of 5–100% B over 30 min at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The target compounds were monitored at 300 nm.

Isolation and structure elucidation

Altemicidin 1 (10 mg) was isolated from a 1.0 L culture of the S. lividans/sbz 1 strain. The culture broth was freeze-dried and subjected to ODS open-column (Cosmosil 75C18-OPN, Nacalai Tesque, Inc.) chromatography, eluted with 50 mM ammonium acetate. The fractions containing 1 were combined, freeze-dried, and further purified by semi-preparative HPLC with a Triant C18 column (10.0 mm I.D. × 250 mm, YMC, Kyoto, Japan), using 5% CH3CN/H2O as the solvent.

Altemicidin (1): white powder; UV (CH3OH) λmax: 300 nm; [a]30D = +7.5 (c = 0.1, H2O); 1H NMR (500 MHz, D2O) δ 7.38 (1H, s), 4.36 (1H, d, J = 14.4 Hz), 4.28 (1H, d, J = 14.4 Hz), 4.28 (1H, overlapping), 2.96 (3H, s), 2.86 (4H, m, overlapping), 2.65 (1H, m), 1.25 (1H, m); 13C NMR (125 MHz, D2O) δ 178.9, 173.4, 163.6, 146.6, 96.3, 75.3, 68.3, 59.6, 44.7, 42.5, 40.6, 40.1, 30.9; HR–ESI–MS m/z [M-H]− 375.0989 (calc. 375.0980, C13H19N4O7S1−)18.

SB-203207 2 (2.2 mg) was isolated from a 2.0 L culture of the S. lividans/sbz 1 and 2 strain. The culture broth was freeze-dried and subjected to ODS open-column chromatography, eluted with CH3OH/H2O (50 mM ammonium acetate) with a gradient from 0 to 50% CH3OH. The fractions containing 2 were combined, freeze-dried, and further purified by semi-preparative HPLC with a Triant C18 column (10.0 mm I.D. × 250 mm, YMC), using 5% CH3CN/H2O (50 mM ammonium acetate) as the solvent.

SB-203207 (2): white powder; UV (CH3OH) λmax: 299 nm; 1H NMR (500 MHz, D2O) δ 7.26 (1H, s), 4.25 (1H, d, J = 14.2 Hz), 4.15 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz), 4.03 (1H, d, J = 14.2 Hz), 3.59 (1H, d, J = 4.3 Hz), 2.86 (3H, s), 2.73 (4H, m, overlapping), 2.54 (1H, m), 1.92 (1H, m), 1.39 (1H, m), 1.13 (2H, m, overlapping), 0.90 (3H, d, J = 7.2 Hz), 0.80 (3H, t, J = 7.5 Hz); 13C NMR (125 MHz, D2O) δ 175.7, 175.5, 173.4, 164.2, 146.6, 96.2, 75.2, 69.3, 60.3, 57.4, 44.7, 42.6, 40.6, 40.0, 36.3, 30.9, 24.0, 14.6, 11.0. HR–ESI–MS m/z [M-H]− 488.1819 (calc. 488.1821, C19H30N5O8S1−)17.

SB-203208 3 (3.5 mg) was isolated from a 2.0 L culture of the S. lividans/sbz 1 and 2 strain. The culture broth was freeze-dried and subjected to ODS open-column chromatography, eluted with CH3OH/H2O (50 mM ammonium acetate) with a gradient from 0 to 50% CH3OH. The fractions containing 3 were combined, freeze-dried, and further purified by semi-preparative HPLC with a COSMOSIL Hilic column (10.0 mm I.D. × 250 mm, Nacalai Tesque, Inc.) using 75% CH3CN/H2O (50 mM ammonium acetate) as the solvent.

SB-203208 (3): white powder; UV (CH3OH) λmax: 297 nm; [α]30 D = +54.7 (c = 0.43, H2O); 1H NMR (500 MHz, D2O) δ 7.25 (6H, m, overlapping), 5.48 (1H, m), 4.16 (1H, d, J = 5.7 Hz), 4.15 (1H, d, J = 14.0 Hz), 4.05 (1H, d, J = 14.0 Hz), 3.56 (1H, d, J = 4.2 Hz), 3.34 (1H, m), 3.05 (1H, dd, J = 12.9 & 5.4 Hz), 2.93 (3H, s), 2.70 (3H, m, overlapping), 2.47 (1H, m), 1.90 (1H, m), 1.35 (3H, d, J = 7.0 Hz), 1.35 (1H, m, overlapping), 1.12 (1H, m), 0.90 (3H, d, J = 7.0 Hz), 0.85 (1H, m), 0.80 (3H, d, J = 7.4 Hz); 13C NMR (125 MHz, D2O) δ 176.3, 175.7, 173.1, 166.7, 164.2, 146.2, 138.5, 129.3, 128.5, 127.9, 97.6, 78.9, 69.9, 60.2, 58.7, 57.1, 44.3, 42.5, 41.5, 40.6, 39.2, 36.3, 30.3, 24.1, 16.6, 14.6, 11.0; HR–ESI–MS m/z [M-H]− 649.2666 (calc. 649.2661, C29H41N6O9S1−)17.

Compound 4; HR–ESI–MS m/z [M-H]− 536.1835 (calc. 536.1821, C23H30N5O8S1−).

For DNPH-7, the enzyme reaction was performed on a 200 μL scale, consisting of 1 mM L-cysteine, 2 mM TCEP, and 10 μM SbzM, in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) at 30 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, 100 x reactions were set up for structure determination. The mixture was then labeled with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine hydrochloride (TCI) (see below for the labeling method), concentrated, and subjected to semi-preparative HPLC with a Triant C18 column (10.0 mm I.D. × 250 mm, YMC), using 55% CH3CN/H2O as the solvents, to afford DNPH-7 (1 mg). UV (CH3CN) λmax: 224 nm, 258 nm 359 nm; 1H and 13C NMR see Supplementary Table 2. HR–ESI–MS m/z [M-H]− 302.0193 (calc. 302.0195).

For DNS-7b, the enzyme reaction was performed on a 200 μL scale, consisting of 1 mM L-cysteine, 2 mM TCEP, and 10 μM SbzM in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer, at 30 ºC for 1 h. Subsequently, 100 x reactions were set up for structure determination. The mixture was then labeled with dansyl chloride (TCI) (see below for the labeling method), concentrated, and subjected to semi-preparative HPLC with a Triant C18 column (10.0 mm I.D. × 250 mm, YMC), using CH3CN (0.1% FA, B) / H2O (0.1% FA, A) as solvents with a gradient from 60% B to 100% B over 15 min, to afford DNS-7b (1 mg). UV (CH3CN) λmax: 207 nm, 255 nm 357 nm; 1H and 13C NMR see Supplementary Table 3. HR–ESI–MS m/z [M+H] + 357.0561 (calc. 357.0573, C14H17N2O5S2+).

Triacetyl-3 was prepared by the acetylation of 3. SB-203208 (3, 1 mg) was dissolved in 2 mL of pyridine, and 10 μL of acetyl chloride was added three times every 30 min. The reaction was monitored by LC–MS. The diacetyl-3 was generated immediately and gradually transformed into the triacetyl-3. Once the diacetyl-3 was completely consumed, 1 mL of water was added. The reaction mixture was freeze-dried and purified by semi-preparative HPLC with a YMC-Triant C18 column (10.0 mm I.D. × 250 mm), using 55% CH3OH/H2O (50 mM ammonium acetate) as the solvents. Triacetyl-3 (0.3 mg): white powder; UV (CH3OH) λmax: 320 nm; [α]30 D = +5.2 (c = 0.025, H2O); 1H NMR (500 MHz, D2O) δ 7.54 (1H, s), 7.14 (5H, m), 5.05 (1H, m), 4.07 (2H, m), 4.03 (1H, d, J = 6.3 Hz), 3.63 (1H, m), 3.12 (5H, m), 2.85 (2H, m), 2.60 (1H, m), 2.48 (1H, m), 2.05 (3H, s), 1.95 (3H, m), 1.90 (3H, m), 1.79 (1H, m), 1.35 (1H, m), 1.19 (1H, m), 1.15 (3H, d, J = 7.3 Hz), 1.07 (1H, m), 0.83 (3H, d, J = 7.0 Hz), 0.75 (3H, t, J = 7.0 Hz). HR–ESI–MS m/z [M-H]− 775.2979 (calc. 775.2978, C35H47N6O12S1−)17.

Gene deletion of sbzF, sbzH, sbzJ, sbzM, sbzN, sbzO, sbzP, sbzQ

In general, sbz1 was divided into two parts to remove the target gene. The first part was amplified and inserted into the pZH1 vector, while the second part was inserted into the pZH2 vector (Supplementary Data set 1). After the sequences were confirmed by gene sequencing, these two vectors were transformed together into the host Streptomyces lividans TK21. These gene deletion strains were cultured in A3M medium, along with the S. lividans TK21 and S. lividans/sbz 1 strains, for 3 days. Subsequently, 1 mL of each culture broth was collected and mixed with the same amount of acetonitrile. After centrifugation and filtration, these samples were analyzed by LC–MS. The LC–MS analysis was performed on a Bruker Compact qTOF mass spectrometer with a Shimadzu Prominence HPLC system, using a HILIC pak VG-50 2D column (2.0 mm I.D. × 150 mm, Shodex, Tokyo, Japan) with a gradient from 80% CH3CN–H2O (0.5% NH3) to 10% over 20 min. The flow rate was 0.2 mL/min. The target was monitored by the negative mode.

The S. lividans/ΔsbzM strain and the S. lividans/ΔsbzJ strain were each inoculated into 50 mL of A3M medium. After culturing the strains for 2 days, 5 mg of 2-sulfamoylacetic acid (5, Enamine) was added to each culture. After an additional 3 days of culture, the broth was centrifuged and mixed with the same amount of acetonitrile. The samples were subjected to an LC–MS analysis after filtration.

Chiral HPLC analysis of β-methylphenylalanine

The chiral HPLC analysis was performed on a Shimadzu Prominence HPLC system equipped with a Chirex phase 3126 (4.6 mm I.D. x 250 mm) column, using 2 mM CuSO4 in 85% H2O/15% CH3CN, at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min, monitored at 210 nm.

The reaction mixture (50 μL) for the assay of SbzB contained 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM β-methylphenylalanine, and 20 μM SbzB in Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer, and was incubated at 30 °C for 1 h. The reactions were quenched by the addition of 50 μL of methanol. Precipitated proteins were removed by centrifugation. A 100 μL portion of the supernatant was subjected to the HPLC analysis, as described above.

Cloning, expression, and purification of recombination proteins

The sbzA, sbzB, sbzC, sbzG, sbzI, sbzJ, sbzK, sbzL, sbzM, and Ssp_IleRS genes were amplified from pZH1-sbz1, pZH2-sbz2, or gDNA of Streptomyces sp. NCIMB 40513 using the primer pairs listed in Supplementary Data set 1, and inserted into the pET28a vector at the HindIII and NdeI sites. The sbzL gene was further amplified from pET28a-sbzI and inserted into the pHSA81 vector. The sbzA, sbzB, sbzC, sbzI, sbzJ, sbzM, and Ssp_IleRS genes were expressed in Rosetta2 (DE3) cells by induction with 0.1 mM IPTG at 16 ºC. The sbzG and sbzK genes were expressed in BLR cells, along with pACYC-sfp, by induction with 0.1 mM IPTG at 16 ºC. pHSA81-sbzL was expressed in S. lividans TK21 in 500-mL baffled flasks containing 100 mL of YEME medium, consisting of 0.3% yeast extract, 0.3% malt extract, 0.5% peptone (Bacto), 1% glucose, 3.4% sucrose, 5 mM MgCl2, and 1% glycine (pH 7.2), for 3 days at 30 °C and 160 min−1. For protein purification, the pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 5 mM imidazole) and lysed by sonication on ice. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation (13,000×g, 60 min, 4 °C). The supernatant was loaded onto Ni-NTA agarose resin (Qiagen) in a gravity flow column, which was washed with Buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol) with 20 mM imidazole followed by elution with Buffer A containing 500 mM imidazole. The purified proteins were concentrated and buffer exchanged into Buffer A, using Amicon Ultra filters. The purified proteins were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

The assay of SbzA

The reaction mixture (50 μL) contained 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM L-isoleucine, 1 mM altemicidin, 10 μL of S30 Premix Plus, 9 μL of T7 S30 Extract (from the S30 T7 High-Yield Protein Expression System, which provides all of the necessary components for translation, Promega), and 10 μM SbzA in Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer, and was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h with shaking. The reactions were quenched by the addition of 50 μL of methanol. Precipitated proteins were removed by centrifugation. A 20 μL portion of the supernatant was subjected to an HPLC analysis, as described above.

The bulk RNA was isolated from Streptomyces sp. NCIMB 40513 culture incubated in YEME medium (0.3% yeast extract, 0.3% malt extract, 0.5% peptone, 1% glucose, 34% sucrose, 1% glycine, 0.1% MgCl2 6H2O, pH 7.0) at 30 ºC for 3 days with the combination of cell wall breakage by phenol and stepwise precipitation with isopropanol44. The reaction mixture (50 μL) contained 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM L-isoleucine, 0.1 mM 1, 3.75 mg/mL bulk RNA and 10 μM SbzA and/or Ssp-IleRS in HEPES (pH 8.0) buffer, and was incubated at 30 °C for 3 h. The reactions were quenched by the addition of 50 μL of acetonitrile. Precipitated proteins were removed by centrifugation. A 20 μL portion of the supernatant was subjected to LC–MS analysis. The LC–MS analysis was performed with a HILIC pak VG-50 2D column (2.0 mm I.D. × 150 mm, Shodex), with a gradient from 80% CH3CN–H2O (0.5% NH3) to 10% over 20 min, at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min.

The substrate screening of AMP-ligases (SbzB and SbzL)

The purified protein (10 μM) was incubated with 1 mM substrate in 100 μL of buffer, containing 2.8 mM hydroxylamine, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.4 U/mL pyrophosphatase (Sigma), 0.5 mM ATP, 10 mM MgCl2, and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). The reaction was incubated for 30 min at 30 °C. Subsequently, a 50 μL portion of the mixture was quenched by adding 100 μL of the working reagent from the malachite green phosphate assay kit (Enzo). After a 20 min incubation at room temperature, the absorbance at 620 nm was measured. The control A620 value was subtracted from the A620 value of the reaction mixture, and then the relative adenylation activity was calculated.

LC–MS analysis of PCPs (SbzG and SbzK)

The analysis was performed on a Bruker Compact qTOF mass spectrometer with a Shimadzu Prominence HPLC system, using a COSMOSIL Protein-R column (2.0 mm I.D. × 150 mm, Nacalai Tesque, Inc.). A gradient elution method was used by employing Solvent A (H2O with 0.1% TFA) for 5 min, followed by a gradient to 100% solvent B (CH3CN with 0.1% TFA) over 20 min, at flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. The mass spectrometric analyses were performed with an electrospray ion source operating in the positive mode. The instrument parameters were as follows: capillary voltage 4500 V; nebulizer gas 3.0 L/min; dry gas 6 L/min; dry temperature 200 ºC; funnel 1RF 400 Vpp; funnel 2RF 400 Vpp; hexapole RF 500 Vpp; collision energy 10 eV; collision RF 1000 Vpp.

The samples were prepared from the reactions of SbzB/L and SbzG/K. The reactions (50 μL) contained 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM β-methylphenylalanine/2-sulfamoylacetic acid, 20 μM SbzB/L, and 250 μM SbzG/K in Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer, and were incubated at 30 ºC for 1 h. The reactions were quenched by the addition of 0.1% TFA, followed by centrifugation and filtration. A 20 μL portion of each sample was subjected to the LC–MS analysis, as described above.

The assay of SbzB, SbzC, and SbzG/K

The reaction mixture (50 μL) for the assay of SbzB, SbzC, and SbzG/K contained 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM β-methylphenylalanine (Enamine Ltd.), 1 mM altemicidin (1) or SB-203207 (2), 20 μM SbzB, 20 μM SbzC, and 250 μM SbzG/K in Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer, and was incubated at 30 ºC overnight. The reactions were quenched by the addition of 50 μL of methanol, followed by centrifugation to remove the precipitated proteins. A 20 μL portion of the supernatant was subjected to the HPLC analysis, as described above.

The assay of SbzL, SbzI, and SbzG/K

The reaction mixture (50 μL) contained 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM 2-sulfamoylacetic acid (6, Enamine Ltd.), 1 mM 5, 20 μM SbzL, 20 μM SbzI, and 250 μM SbzG/K in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer, and was incubated at 30 ºC overnight. The reactions were quenched by the addition of 50 μL of methanol. The precipitated proteins were removed by centrifugation. A 20 μL portion of the supernatant was subjected to the HPLC analysis, as described above.

The assay of SbzM and SbzJ

The reaction mixture (50 μL) contained 2 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), 1 mM L-cysteine, 1 mM NAD+, 10 μM SbzM, and 10 μM SbzJ, in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 8.0), and was incubated at 30 ºC for 30 min.

The analysis of the labeled compounds

For carboxy group labeling, 20 μL of the reaction mixture was treated with 20 μL of 100 mM KH2PO4 and 100 μL of 4-bromophenacyl bromide (TCI) solution, and incubated at 77 ºC for 60 min.

For amino group labeling, 50 μL of the reaction mixture was treated with 50 μL of 80 mM Li2CO3, 70 μL of CH3CN, and 30 μL of dansyl chloride (TCI), and incubated at 25 ºC for 1 h.

For aldehyde labeling, 50 μL of the reaction mixture (reaction in phosphate buffer instead of Tris buffer) was treated with 50 μL of 1 M HCl, 50 μL of CH3OH, and 50 μL of 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine hydrochloride (TCI), and incubated at 40 °C for 1 h.

After centrifugation, 20 μL of the supernatant was subjected to an HPLC analysis. The solvent system was H2O with 0.1% formic acid (solvent A) and CH3CN with 0.1% formic acid (solvent B), with a gradient of 5–100% B over 30 min. The target was monitored at 254 nm.

LC–MS analysis of the reactions with labeling was performed with a COSMOSIL 5C18-AR-II column (2.0 mm I.D. × 150 mm, Nacalai Tesque, Inc.) with a gradient from 5% CH3CN–H2O (50 mM ammonium acetate) to 100% over 20 min, at a flow rate of 0.1 mL/min.

LC–MS analysis of 5 and 7

The LC–MS analysis of the reactions without labeling (quenched by the addition of 50 μL of acetonitrile) was performed with a HILIC pak VG-50 2D column (2.0 mm I.D. × 150 mm, Shodex) with a gradient from 80% CH3CN–H2O (0.5% NH3) to 10% over 20 min, at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. The target was monitored by the negative mode.

H218O incorporation

H218O incorporation by SbzM and SbzJ was assessed in a reaction (50 μL), containing 2 mM TCEP, 1 mM L-cysteine, 1 mM NAD+, 10 μM SbzM, and 10 μM SbzJ in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) (43 μL of water), incubated at 30 ºC for 1 h. The reactions were quenched by the addition of 50 μL of CH3CN. The LC–MS analysis of the reactions was performed as described above.

H218O incorporation by SbzM was assessed in a reaction (50 μL), containing 2 mM TCEP, 1 mM L-cysteine, 10 μM SbzM, and 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) (45.5 μL of water), incubated at 30 °C for 1 h. The reactions were quenched by the addition of 50 μL of acetonitrile. The LC–MS analysis of the reactions was performed with a HILIC pak VG-50 2D column (2.0 mm I.D. × 150 mm, Shodex), with a gradient from 80% CH3CN–H2O (50 mM ammonium acetate, pH 8.0) to 10% over 20 min, at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. The target was monitored by the negative mode.

Kinetic analysis of SbzM

To determine the kinetic parameters of SbzM, the temperature, pH, and time course of the enzymatic assay were monitored. The optimized assays contained the substrate, L-cysteine (0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8 mM, in duplicate), and purified SbzM (6 μM). The substrate was mixed with TCEP for 30 min before the assay. The enzyme, in 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 9.0), was pre-incubated at 30 ºC for 3 min. A 1 μL portion of each substrate mixture was added and further incubated for 2 min at 30 ºC. The enzymatic reactions were stopped by the addition of 50 μL of acetonitrile. Consumption of the substrate was quantified by an LC–MS analysis. The kinetics values were calculated with GraphPad Prism 6.0 (San Diego, California, USA). The LC–MS analysis was conducted with a Bruker Compact qTOF mass spectrometer with a Shimadzu Prominence HPLC system, using a HILIC pak VG-50 2D column (2.0 mm I.D. × 150 mm, Shodex) with a gradient from 80% CH3CN/H2O (20 mM formic acid) to 10% over 15 min. The chromatograms were extracted at an m/z 122.0270 ± 0.01 ([M+H]+ for L-cysteine).

Metal chelation and reconstitution of SbzM

The purified SbzM enzyme was incubated with 1 mM EDTA at 30 °C for 1 h. The chelation of the active-site metal was verified by the loss of enzyme activity (dansyl chloride method as described above). The excess EDTA was subsequently removed by dialysis at 4 °C overnight. Different metal ions (Fe2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Mn2+, Ni2+, Co2+) were supplemented to the dialyzed apo-protein at a 2 mM concentration and incubated at 30 °C for 1 h. The recovery of the enzyme activity was subsequently measured.

ICP-MS analysis of SbzM

The metal contents of SbzM were determined by inductive-coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) using a Thermo iCAP-Q system under standard operating conditions. The protein samples were prepared as follows: the initial protein solution (10 μM) was taken as a positive control; the protein solution after 1 mM EDTA treatment and twice dialysis was taken as a negative control; then the protein solutions after 2 mM Fe, Cu, and Ni treatment and followed by twice dialysis were taken as Fe, Cu, and Ni, respectively (final metal concentration in the solution is 0.014 μM). This analysis indicated that the content of Fe and Ni increase significantly while no increase observed for other metals, respectively.

Hydrolysis of 1 to prepare 6

Altemicidin 1 (2 mg) was hydrolyzed with 4 M HCl (1.5 mL) at 50 °C overnight. The reaction mixture was freeze-dried and purified by chromatography on a Cosmosil HILIC column (10 mm I.D. × 250 mm, Nacalai Tesque, Inc.; flow rate 3 mL/min; 70% CH3CN/H2O containing 50 mM ammonium acetate). 6: white powder; UV (CH3OH) λmax: 294 nm; HR–ESI–MS m/z [M-H]− 254.1148 (calc. 254.1146, C11H16N3O4−).

Isotope-labeled precursor feeding

L-cysteine-13C3, 15N (100 mg) was fed to the altemicidin-producing strain (S. lividans/sbz 1) after 48 h, 60 h, and 72 h incubations in 100 mL of Hijacking medium (0.3% soy broth, 0.5% pharma media, 0.3% yeast extract, 2.0% black treacle, 2.0% glucose, and 0.4% CaCO3). After 6 days of fermentation, the labeled 1 was isolated as described above.

Reporting Summary

Further information on experimental design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (JSPS KAKENHI grant numbers JP16H06443, JP17H04763, and JP18K19139), JST/NSFC Strategic International Collaborative Research Program Japan–China, and Kobayashi International Scholarship Foundation. We appreciate GlaxoSmithKline for providing Streptomyces sp. NCIMB 40513 and Institute of Microbial Chemistry for providing the authentic sample of altemicidin. We also thank Dr. Kazuo Furihata for discussion on NMR, Dr. Hiroyasu Onaka for providing pTYM19ep, Dr. Michihiko Kobayashi for providing pHSA81, and Dr. Toshiyuki Kan for providing the authentic sample of SB-203207.

Author contributions

T.A. and I.A. designed the experiments. Z.H. and T.A. performed the experiments. Z.H., T.A., Z.M., and I.A. analyzed the data. Z.H., T.A., and I.A. wrote the paper.

Data availability

The DNA sequences of altemicidin, SB-203207, and SB-203208 biosynthetic gene clusters (sbz cluster) and Ile-tRNA synthetase gene from Streptomyces sp. NCIMB40513 (Ssp-IleRS) were registered as LC420052 and LC420053 in GenBank, respectively. The data that support the findings are available on request. A reporting summary for this article is available as a Supplementary Information file.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contributions to the peer review of this work. Peer Reviewer Reports are available.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Zhijuan Hu, Takayoshi Awakawa.

Contributor Information

Takayoshi Awakawa, Email: awakawa@mol.f.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Ikuro Abe, Email: abei@mol.f.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-08093-x.

References

- 1.Hesse, M. Alkaloids Nature's Curse or Blessing. (Verlag Helvetica Chimica Acta, Zürich, Switzerland, and Wiley-VCH Weinheim, Germany, 2002).

- 2.Jin Z. Muscarine, imidazole, oxazole and thiazole alkaloids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2013;30:869–915. doi: 10.1039/c3np70006b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh CT, Haynes SW, Ames BD. Aminobenzoates as building blocks for natural product assembly lines. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2012;29:37–59. doi: 10.1039/C1NP00072A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sánchez C, Méndez C, Salas JA. Indolocarbazole natural products: occurrence, biosynthesis, and biological activity. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2006;23:1007–1045. doi: 10.1039/B601930G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petkowski JJ, Bains W, Seager S. Natural products containing a nitrogen-sulfur bond. J. Nat. Prod. 2018;81:423–446. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waldman AJ, Ng TL, Wang P, Balskus EP. Heteroatom-heteroatom bond formation in natural product biosynthesis. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:5784–5863. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugai Y, Katsuyama Y, Ohnishi Y. A nitrous acid biosynthetic pathway for diazo group formation in bacteria. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016;12:73–75. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waldman AJ, Balskus EP. Discovery of a diazo-forming enzyme in cremeomycin biosynthesis. J. Org. Chem. 2018;83:7539–7546. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.8b00367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du YL, He HY, Higgins MA, Ryan KS. A heme-dependent enzyme forms the nitrogen-nitrogen bond in piperazate. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017;13:836–838. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuda K, et al. Discovery of an unprecedented hydrazine-forming machinery in bacteria. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:9083–9086. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b05354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baunach M, Ding L, Willing K, Hertweck C. Bacterial synthesis of unusual sulfonamide and sulfone antibiotics by flavoenzyme-mediated sulfur dioxide capture. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2015;54:13279–13283. doi: 10.1002/anie.201506541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao C, et al. Characterization of biosynthetic genes of ascamycin/dealanylascamycin featuring a 59-O-sulfonamide moiety in Streptomyces sp. JCM9888. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brooks, G. T. in Sulphur-containing Drugs and Related Organic Compounds, Vol. 1, part A (ed Damani, L. A.) 60–93 (Ellis Horwood, New York, 1989).

- 14.Takahashi A, Kurasawa S, Ikeda D, Okami Y, Takeuchi T. Altemicidin, a new acaricidal and antitumor substance. I. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation and physico-chemical and biological properties. J. Antibiot. 1989;42:1556–1561. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi A, Kurasawa S, Ikeda D, Okami Y, Takeuchi T. Altemicidin, a new acaricidal and antitumor substance. II. Structure determination. J. Antibiot. 1989;42:1562–1566. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stefanska AL, Cassels R, Ready SJ, Warr SR. SB-203207 and SB-203208, two novel isoleucyl tRNA synthetase inhibitors from a Streptomyces sp. I. Fermentation, isolation and properties. J. Antibiot. 2000;53:357–363. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.53.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Houge-Frydrych CSV, Gilpin ML, Skett PW, Tyler JW. SB-203207 and SB-203208, Two novel isoleucyl tRNA synthetase inhibitors from a Streptomyces sp. II. Structure determination. J. Antibiot. 2000;53:364–372. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.53.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kende AS, Liu K, Jos Brands KM. Total synthesis of (–)-altemicidin: a novel exploitation of the Potier–Polonovski rearrangement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:10597–10598. doi: 10.1021/ja00147a032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kan T, Kawamoto Y, Asakawa T, Furuta T, Fukuyama T. Synthetic studies on altemicidin: Stereocontrolled construction of the core framework. Org. Lett. 2008;10:169–171. doi: 10.1021/ol701940f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirooka, Y. et al. Enantioselective synthesis of SB-203207. Org. Lett. 16, 1646–1649 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Reimer JM, Haque AS, Tarry MJ, Schmeing TM. Piecing together nonribosomal peptide synthesis. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2018;49:104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang YT, et al. In vitro characterization of enzymes involved in the synthesis of nonproteinogenic residue (2S,3S)-β-methylphenylalanine in glycopeptide antibiotic mannopeptimycin. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:2480–2487. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nogle LM, Mann CW, Watts WL, Zhang Y. Preparative separation and identification of derivatized β-methylphenylalanine enantiomers by chiral SFC, HPLC and NMR for development of new peptide ligand mimetics in drug discovery. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2006;40:901–909. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2005.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakashima Y, Egami Y, Kimura M, Wakimoto T, Abe I. Metagenomic analysis of the sponge Discodermia reveals the production of the cyanobacterial natural product kasumigamide by ‘entotheonella’. PLoS One. 2016;11:1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newton GL, Fahey RC. Mycothiol biochemistry. Arch. Microbiol. 2002;178:388–394. doi: 10.1007/s00203-002-0469-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vetting MW, et al. Structure and functions of the GNAT superfamily of acetyltransferases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005;433:212–226. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Wagoner RM, Clardy J. FeeM, an N-acyl amino acid synthase from an uncultured soil microbe: structure, mechanism, and acyl carrier protein binding. Structure. 2006;14:1425–1435. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ye Y, et al. Unveiling the biosynthetic pathway of the ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptide ustiloxin b in filamentous fungi. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2016;55:8072–8075. doi: 10.1002/anie.201602611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lei L, Cherukuri KP, Alcolombri U, Meltzer D, Tawfik DS. The dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) lyase and lyase-like cupin family consists of bona fide DMSP lyases as well as other enzymes with unknown function. Biochemistry. 2018;57:3364–3377. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schnicker NJ, De Silva SM, Todd JD, Dey M. Structural and biochemical insights into dimethylsulfoniopropionate cleavage by cofactor-bound DddK from the prolific marine bacterium Pelagibacter. Biochemistry. 2017;56:2873–2885. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fetzner S. Ring-cleaving dioxygenases with a cupin fold. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:2505–2514. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07651-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merkens H, Kappl R, Jakob RP, Schmid FX, Fetzner S. Quercetinase QueD of Streptomyces sp. FLA, a monocupin dioxygenase with a preference for nickel and cobalt. Biochemistry. 2008;47:12185–12196. doi: 10.1021/bi801398x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nureki O, et al. Enzyme structure with two catalytic sites for double-sieve selection of substrate. Science. 1998;280:578–582. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakama T, Nureki O, Yokoyama S. Structural basis for the recognition of isoleucyl-adenylate and an antibiotic, mupirocin, by isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:47387–47393. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109089200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burbaum JJ, Schimmel P. Structural relationships and the classification of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:16965–16968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moutiez M, Belin P, Gondry M. Aminoacyl-tRNA-utilizing enzymes in natural product biosynthesis. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:5578–5618. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simmons CR, et al. A putative Fe2+-bound persulfenate intermediate in cysteine dioxygenase. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11390–11392. doi: 10.1021/bi801546n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blaesse M, Kupke T, Huber R, Steinbacher S. Crystal structure of the peptidyl-cysteine decarboxylase EpiD complexed with a pentapeptide substrate. EMBO J. 2000;19:6299–6310. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Opitz G. Sulfines and sulfenes - the S-oxides and S,S-dioxides of thioaldehydes and thioketones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1967;6:107–194. doi: 10.1002/anie.196701071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCaw PG, Buckley NM, Collins SG, Maguire AR. Generation, reactivity and uses of sulfines in organic synthesis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016;2016:1630–1650. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201501538. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao SS, et al. Biosynthesis of heptacyclic duclauxins requires extensive redox modifications of the phenalenone aromatic polyketide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:6991–6997. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b03705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stipanuk MH, Simmons CR, Karplus PA, Dominy JE. Thiol dioxygenases: unique families of cupin proteins. Amino Acids. 2011;41:91–102. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0518-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anand R, Dorrestein PC, Kinsland C, Begley TP, Ealick SE. Structure of oxalate decarboxylase from Bacillus subtilis at 1.75 Å resolution. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7659–7669. doi: 10.1021/bi0200965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ehrenstein G. von. Biochemistry. 1965;1273:588–596. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The DNA sequences of altemicidin, SB-203207, and SB-203208 biosynthetic gene clusters (sbz cluster) and Ile-tRNA synthetase gene from Streptomyces sp. NCIMB40513 (Ssp-IleRS) were registered as LC420052 and LC420053 in GenBank, respectively. The data that support the findings are available on request. A reporting summary for this article is available as a Supplementary Information file.