Abstract

Four new cyclohexylideneacetonitrile derivatives 1–4, named menisdaurins B–E, as well as three known cyclohexylideneacetonitrile derivatives—menisdaurin (5), coclauril (6), and menisdaurilide (7)—were isolated from the hypocotyl of a mangrove (Bruguiera gymnorrhiza). The structures of the isolates were elucidated on the basis of extensive spectroscopic analysis. Compounds 1–7 showed anti-Hepatitis B virus (HBV) activities, with EC50 values ranging from 5.1 ± 0.2 μg/mL to 87.7 ± 5.8 μg/mL.

Keywords: antiviral, Bruguiera gymnorrhiza, cyclohexylideneacetonitrile derivative

1. Introduction

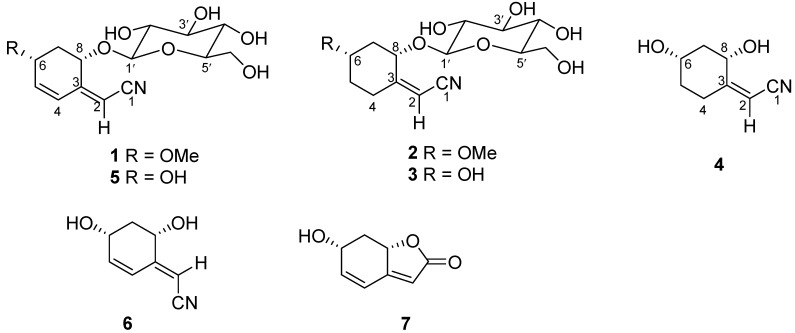

Bruguiera gymnorrhiza (L.) Savigny (Rhizophoraceae) is a common buttressed tree found in the mangrove forests [1] which are native to many countries of southern and eastern Africa, Asia, and northern Australia [2]. Different parts of these mangrove plants have traditionally been used as herbal medicines in Thailand and China [2]. Previous phytochemical investigations on B. gymnorrhiza have shown the presence of diterpenes, triterpenes, flavonoids, aromatic compounds, and sulfur-containing compounds [1,2,3,4,5,6]. As part of our continuing program aimed at exploring the bioactive natural products from mangrove plants collected on the coast of South China Sea [7,8], four new cyclohexylideneacetonitrile derivatives 1–4 (Figure 1), which have been named menisdaurins B–E, as well as three known cyclohexylideneacetonitrile derivatives—menisdaurin (5) [9], coclauril (6) [10], and menisdaurilide (7) [11]—were isolated from the hypocotyl of a mangrove B. gymnorrhiza. Herein, we will discuss the isolation, structural elucidation, and antiviral activity of these secondary metabolites.

Figure 1.

Secondary metabolites 1–7.

2. Results and Discussion

The molecular formula of menisdaurin B (1), a yellow powder, was established as C15H21NO7 based on the NMR and HRESIMS data ([M − H]−, m/z: 326.1238; calcd. for C15H20NO7 m/z: 326.1240). A characteristic, sharp band at 2225 cm−1 in the IR spectrum and a signal at δC 117.9 (C-1) in the 13C-NMR showed the presence of an α,β-unsaturated nitrile [9]. The 1H- and 13C-NMR (Table 1) data suggested the presence of a sugar joined to an aglycone by an α,β-glycosidic linkage (anomeric proton and carbon; δH 4.38 (1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz, H-1′) and δC 102.3 (C-1′), respectively). The acid hydrolysis of 1 with HCl gave a d-glucose, which was confirmed by TLC. In the 1H-NMR spectrum of the aglycone in 1 (Table 1), two olefinic protons at δH 6.20 (1H, d, J = 10.0 Hz, H-4) and 6.18 (1H, dd, J = 10.0, 2.5 Hz, H-5), two methine protons at δH 4.72 (1H, dd, J = 10.2, 3.5 Hz, H-8) and 4.45 (1H, ddd, J = 9.0, 5.5 and 2.5 Hz, H-6), and one methene proton at δH 2.39 (1H, ddd, J = 12.5, 5.5 and 3.5 Hz, H-7a) and 1.62 (1H, ddd, J = 12.5, 10.2 and 9.0 Hz, H-7b), and also from the COSY and HMQC, the sequence from C-4 to C-8 was established as –CH–CH–CH(O)–CH2–CH(O)–. The remaining methine signal (δC 97.2 (C-2) and δH 5.66 (1H, d, J = 1.8 Hz, H-1)) and a quaternary carbon (δC 155.2 (C-3)) resembled the cyanomethylene group of menisdaurin (1) [9] also isolated from the same plant B. gymnorrhiza, whose structure was confirmed by comparison the [α]D, IR spectrum and detailed NMR data with those in the literature [9,12,13]. In contrast to the low optical rotation of a (−145°, in MeOH, c 0.5) reported for menisdaurin in [12], we measured an (−78.2°, in MeOH, c 0.2) for our isolated menisdaurin (5). Although this differs from the value given for menisdaurin in [12], it is acceptable considering the compound 5 was the same substance, namely menisdaurin. This is underlined by a characteristic sharp band at 2223 cm−1 in the IR spectrum and a signal at δC 118.5 (C-1) in the 13C-NMR showed the presence of an α,β-unsaturated nitrile, which are in good agreement with those of menisdaurin in [9,13]. Finally the detailed NMR data given for 5 fit the reported data of menisdaurin in [9,12,13].

Table 1.

1H- and 13C-NMR data of 1–4.

| No. | δC, Mult | 1 a | 2 a | 3 a | 4 b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δH (J in Hz) | δC, Mult | δH (J in Hz) | δC, Mult | δH (J in Hz) | δC, Mult | δH (J in Hz) | ||

| 1 | 117.9, C | 117.1, C | 118.7, C | 116.8, C | ||||

| 2 | 97.2, CH | 5.66 (d, 1.8) | 94.7, CH | 5.53 (d, 1.5) | 94.3, CH | 5.51 (d, 1.8) | 89.4, CH | 5.6 (s) |

| 3 | 152.2, C | 166.0, C | 166.5, C | 170.5, C | ||||

| 4a | 125.4, CH | 6.20 (d, 10.0) | 29.7, CH2 | 2.46 (d, 11.9) | 29.6, CH2 | 2.45 (d, 11.0) | 25.2, CH2 | 2.79 (d, 11.0) |

| 4b | 2.25 (dd, 11.9, 7.8) | 2.11 (dd, 11.0, 7.8) | 2.59 (dd, 11.0, 7.8) | |||||

| 5a | 144.3, CH | 6.18 (dd, 10, 2.5) | 36.4, CH2 | 1.86–1.92 (m) | 36.3, CH2 | 1.69–1.74 (m) | 33.5, CH2 | 1.87–1.93 (m) |

| 5b | 1.19–1.24 (m) | 1.36–1.42 (m) | 1.61–1.67 (m) | |||||

| 6 | 62.8, CH | 4.45 (ddd, 9.0, 5.5, 2.5) | 63.9, CH | 3.92–3.87 (m) | 67.2, CH | 3.75–3.70 (m) | 67.7, CH | 4.48–4.54 (m) |

| 7a | 37.1, CH2 | 2.39 (ddd, 12.5, 5.5, 3.5) | 36.1, CH2 | 1.87 (ddd, 11.5, 5.2, 3.5) | 41.1, CH2 | 2.09 (ddd, 11.3, 5.0, 3.8) | 42.9, CH2 | 2.18 (ddd, 10.1, 5.0, 3.3) |

| 7b | 1.62 (ddd, 12.5, 10.2, 9.0) | 1.17 (ddd, 11.5, 9.7, 8.8) | 1.55 (ddd, 11.3, 9.4, 8.5) | 1.56 (ddd, 10.1, 9.3, 8.5) | ||||

| 8 | 73.2, CH | 4.72 (dd, 10.2, 3.5) | 73.9, CH | 3.08 (dd, 9.7, 3.5) | 74.8, CH | 3.10 (dd, 9.4, 3.8) | 65.7, CH | 4.17 (dd, 9.3, 3.3) |

| 1′ | 102.3, CH | 4.38 (d, 7.8) | 102.8, CH | 4.15 (d, 7.3) | 102.6, CH | 4.27 (d, 7.6) | ||

| 2′ | 73.8, CH | 3.16 (ddd, 8.7, 7.8, 4.5) | 75.9, CH | 2.95 (ddd, 8.5, 7.3, 4.3) | 75.8, CH | 3.09 (ddd, 8.4, 7.6, 4.3) | ||

| 3′ | 77.4, CH | 3.39 (ddd, 8.7, 8.7 4.2) | 77.6, CH | 3.10 (ddd, 8.7, 8.5, 4.5) | 78.8, CH | 3.11 (ddd, 8.4, 8.3, 4.5) | ||

| 4′ | 70.6, CH | 3.01 (ddd, 8.7, 8.7, 5.4) | 70.4, CH | 3.04 (ddd, 8.7, 8.7, 5.2) | 71.9, CH | 3.01 (ddd, 8.3, 7.8, 5.2) | ||

| 5′ | 77.3, CH | 3.11 (ddd, 8.7, 6.8, 6.2) | 77.5, CH | 2.94 (ddd, 8.7, 6.4, 2.4) | 78.6, CH | 3.05 (ddd, 7.8, 6.4, 2.2) | ||

| 6′a | 61.8, CH2 | 3.45 (ddd, 11.8, 6.2, 5.2) | 61.4, CH2 | 3.39 (ddd, 11.3, 6.2, 5.1) | 63.0, CH2 | 3.39 (ddd, 11.0, 6.2, 5.1) | ||

| 6′b | 3.98 (ddd, 11.8, 6.8, 2.3) | 3.65 (ddd, 11.3, 6.8, 2.2) | 3.65 (ddd, 11.0, 6.5, 2.2) | |||||

| 6-OMe | 49.2, CH3 | 49.2, CH3 | ||||||

| 6-OH | 4.79 (d, 3.5) | |||||||

| 2′-OH | 4.97 (d, 4.5) | 5.09 (d, 4.3) | 5.02 (d, 4.3) | |||||

| 3′-OH | 4.94 (d, 4.2) | 5.04 (d, 4.5) | 5.01 (d, 4.5) | |||||

| 4′-OH | 4.93 (d, 5.4) | 5.02 (d, 5.2) | 4.99 (d, 5.2) | |||||

| 6′-OH | 4.17 (d, 5.2) | 4.15 (d, 5.1) | 4.13 (d, 5.1) | |||||

a In DMSO-d6, 600 MHz for 1H- and 150 MHz for 13C-NMR; b In CD3OD, 600 MHz for 1H- and 150 MHz for 13C-NMR.

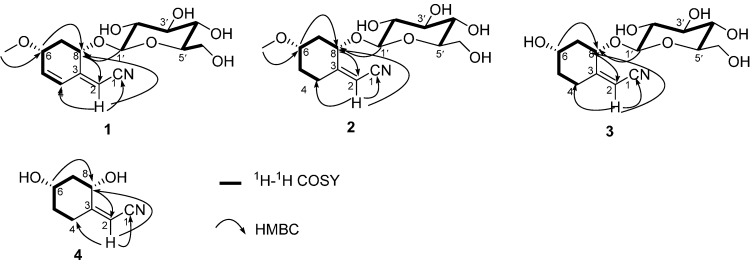

The spin systems of H-1′/H-2′/H-3′/H-4′/H-5′/H2-6′ and H-4/H-5/H-6/H2-7/H-8 present in 1, as the analysis of the 1H-1H COSY correlations revealed, were assembled with the assistance of the HMBC correlations (Figure 2). The structure of 1 was further confirmed by the HMBC spectrum (Figure 2). There were significant long range couplings between H-2 and C-1, C-4 and C-8, which further established the position of the α,β-unsaturated nitrile. The anomeric proton H-1′ has a long range correlation with C-8 which showed that the sugar moiety is attached to C-8 of the aglycone. Moreover, the methoxyl attached to C-6 was secured by the HMBC correlation of OCH3 to C-6.

Figure 2.

Selected 1H-1H COSY and HMBC correlations of 1–4.

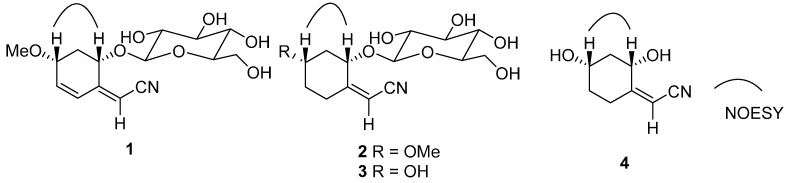

The stereochemistry of 1 was established by a comprehensive analysis of the 1H-NMR coupling constants, NOESY (Figure 3), 13C-NMR and CD data. The large coupling characteristics showed the pseudodiaxial relationships of H-7b (ddd, J7b,8 = 10.2 Hz, J7b,6 = 9.0 Hz, and J7a,7b = 12.5 Hz) with both H-6 and H-8, together with a NOE correlation between H-6 and H-8 in the NOESY spectrum (Figure 3), and demonstrated that H-6, H-7b and H-8 occupied the pseudodiaxial positions and that H-6 and H-8 were oriented on the same side of the ring system in 1. Compound 1 showed a in MeOH of −44.7°. The reported value for menisdaurin was negative ( −145°) [12], whose stereochemistry of the aglycone and β-glucosyl residue have been established by the X-ray single crystallographic analysis [14] and enzymatic hydrolysis [15], respectively. Moreover, the NMR data of in C-8 (δC 73.2) in 1 is identical to that of C-8 (δC 73.2) observed in menisdaurin [13], which indicated that C-8 in 1 has the same absolute stereostructure as C-8 in menisdaurin. Finally, the absolute configurations of C-6 and C-8 were further confirmed by its CD spectrum, in which a negative Cotton effect by the cyclohexene group was show at 215 nm (Δε215nm−25.5). The appplicaton of the octant rule [16] to the compound depicted in the formula of 1 found that the expected sign of the Cotton effect should be negative. Accordingly, the absolute configurations at the chiral centres C-6 and C-8 of the aglycone in 1 were assigned as S and R, respectively. The structure of 1 is thus predicted to be as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 3.

Selected NOESY correlations of 1–4.

Menisdaurin C (2), was obtained as a yellow powder, and had the molecular formula C15H23NO7 as deduced from the HR-ESI-MS ([M − H]−, m/z: 328.1394; calcd for C15H22NO7 m/z: 328.1396) and NMR data (Table 1). Furthermore, its NMR spectra and the sharp band at 2222 cm−1 in the IR spectrum established that 1 possessed an α,β-unsaturated nitrile [9] and a β-glucosyl moiety, which were greatly similar to those of 1 and menisdaurin (5), indicating that 2, 1, and 5 are structurally related. A careful comparison of the 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra of 2 with those of 1 revealed that the C-4 and C-5 are double bonds in 1, while C-4 and C-5 in 2 are methylene groups.

It was possible to differentiate between the separate spin systems of H-1′/H-2′/H-3′/H-4′/H-5′/H2-6′ and H2-4/H2-5/H-6/H2-7/H-8 from the 1H-1H COSY spectrum of 2 (Figure 2). These data, together with the key HMBC correlations between H-1′/C-8; H-2/C-1, C-4, and C-8; and MeO-6/C-6 (Figure 2), permitted the elucidation of the carbon skeleton of 2.

The relative configuration of the aglycone in 2 was determined by the NOESY experiment (Figure 3) and 1H-NMR J values. In the 1H-NMR, a large coupling constant (J7b,8 = 9.7 Hz) was observed for H-8, which required a trans-diaxial relationship between H-8 and H-7b. In addition, a NOESY correlation between H-8 and H-6 indicated that these two protons were in the axial orientations and cis to one another.

Compound 2 showed a in MeOH of −56.2°. The corresponding reported value for menisdaurin was negative ( −145°) [12], and the observed value for 1 was −44.7°. The NMR data of C-8 (δC 73.9) in 2 was very similar to that observed at C-8 (δC 73.2) in compound 1 and C-8 (δC 73.2) in menisdaurin [13], which suggested that the absolute configuration of C-8 was the same as those of C-8 in compound 1 and menisdaurin. Furthermore, the absolute configurations of C-6 and C-8 were confirmed by its CD spectrum, in which a negative Cotton effect caused by the nitrylidenecyclohexane group appeared at 215 nm (Δε215nm−22.7), the applicaton of the octant rule to the compound depicted as compound 2 found that the expected sign of the Cotton effect should be negative [17]. Therefore, the absolute configuration of the aglycone in 2 was assigned as S and R, respectively. Compound 2 is thus determined as shown in Figure 1 on the basis of the above spectroscopic evidence.

Menisdaurin D (3), was obtained as a yellow powder, and the molecular formula C14H21NO7 was obtained from the HR-ESI-MS ([M − H]−, m/z: 314.1238; calcd for C14H20NO7 m/z: 314.1240) and NMR spectral data (Table 1). The molecular formula indicated that 3 was a derivative of 2. Comparison of the 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra of 3 with those of 2 confirmed the overall similarity between their structures. However, a careful comparison of the 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra of 3 with those of 2 revealed that the major differences between 2 and 3 were the 6-OMe in 2 and an especially downfield signal of the hydroxyl group 6-OH at δH 4.79 in 3, and the relative up shift of C-6 at δC 67.2 in 3.

The molecular framework was established by the 1H-1H COSY and HMBC correlations (Figure 2). The comprehensive analysis of the 1H-1H COSY correlations of 3 established the spin systems of H-1′/H-2′/H-3′/H-4′/H-5′/H2-6′ and H2-4/H2-5/H-6/H2-7/H-8. The MeO-6 group attached to C-6 was confirmed by the HMBC correlations from MeO-6 to C-6. The planar structure of 3 was further confirmed by the HMBC correlations between H-2 and C-1, C-4, and C-8, which established the position of the α,β-unsaturated nitrile, and the correlations between the anomeric proton H-1′ and C-8, which showed that the sugar moiety is attached to C-8 of the aglycone.

The NOESY correlation of H-8 and H-6 (Figure 3) and the a large coupling constant (J7b,8 = 9.4 Hz) confirmed that these two protons were cofacial and were at the axial positions. Compound 3 showed a in MeOH of −76.2°. The reported value for menisdaurin was negative ( −145°) [12], and the observed values for 1 and 2 were −44.7° and −56.2°, respectively. Combined with the NMR data of C-8 (δC 74.8) in 3 is greatly similar with that of C-8 (δC 73.9) observed in 2 and the key NOESY correlation of H-6 and H-8, the configurations of C-6 and C-8 in compound 3 should be the same as those of C-6 and C-8 in 2, namely S and R, respectively. Moreover, the Cotton effect values of both 2 and 3 showed negative Cotton effects at 215 nm (Δε215nm−22.7) and (Δε215nm−42.6), respectively. Compound 3 is identified as a derivative of 2 on the basis of the above spectroscopic evidence.

Menisdaurin E (4) was obtained as colorless plates, and the molecular formular C8H11NO2 was obtained from the HR-ESI-MS data ([M + Na]+, m/z: 176.0679; calcd for C8H11NO2Na m/z: 176.0687) and NMR spectral data (Table 1). A characteristic, sharp band at 2219 cm−1 in the IR spectrum and a signal at δC 116.8 (C-1) in the 13C-NMR showed the presence of an α,β-unsaturated nitrile [9]. Analyses of the 13C-NMR data indicated that 4 is the aglycone of compound 3.

The molecular framework was established by the 1H-1H COSY and HMBC correlations (Figure 2). The comprehensive analysis of the 1H-1H COSY correlations of 4 established the spin system of H2-4/H2-5/H-6/H2-7/H-8. The planar structure of 4 was further confirmed by the HMBC correlations between H-2 and C-1, C-4, and C-8, which established the position of the α,β-unsaturated nitrile.

The NOESY correlation of H-8 and H-6 (Figure 3) and the large coupling constant (J7b,8 = 9.3 Hz) confirmed that these two protons were cofacial and were at the axial positions. Compound 4 showed a in MeOH of −47.3°. The observed value for 3 was −76.2°. Moreover, the Cotton effect values of both 3 and 4 showed negative Cotton effects at 215 nm (Δε215nm −42.6) and (Δε215nm −33.4), respectively. Compound 4 is identified as the aglycone of 3 on the basis of the above spectroscopic evidence.

A comparison of the anti-HBV activities for selected sets of 1–7 are displayed in Table 2. The standard deviations listed in Table 2 for the EC50 and CC50 values were calculated using the coefficients of variance produced by each regression analysis. A selectivity index (SI) was calculated for each compound and is expressed as the ratio of CC50 to EC50 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Anti-HBV activity of 1–7.

| Compounds | EC50 (μg/mL) | CC50 (μg/mL) | SI (CC50/EC50) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 23.8 ± 0.5 | 178.2 ± 13.3 | 7.5 |

| 2 | 30.7 ± 1.0 | 164.9 ± 10.4 | 5.4 |

| 3 | 19.4 ± 0.3 | 182.0 ± 6.8 | 9.4 |

| 4 | 8.7 ± 1.1 | 72.3 ± 4.1 | 8.3 |

| 5 | 5.1 ± 0.2 | 57.8 ± 3.9 | 11.3 |

| 6 | 7.6 ± 0.5 | 83.9 ± 2.3 | 11.0 |

| 7 | 80.7 ± 5.8 | 214.8 ± 14.7 | 2.7 |

| Lamivudine | 0.1 ± 0.03 | / | / |

According to the results described in Table 2, it is easy to understand that most of the tested compounds 1–7 showed moderate antiviral properties. In general, this study revealed the activity order as 5 > 6 > 4 > 3 > 1 > 2 > 7. Compound 5 had the most effective activity against HBV replication in the human hepatoblastoma cell line. Compound 7, by comparison, demonstrated a lesser degree of specific activity against HBV replication.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. General Procedures

UV spectra were recorded in MeOH on a Lambda 35 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer, Wellesley, MA, USA). The IR spectra were measured in KBr on a WQF-410 FT-IR spectrophotometer (Beifen-Ruili, Beijing, China). NMR spectra were recorded on an AV 600 MHz NMR spectrometer with TMS as an internal standard (Bruker, Bremen, Germany). HRESIMS data were obtained from a Bruker Maxis mass spectrometer (Bruker). A Waters-2695 HPLC system, using a Sunfire™ C18 column (150 mm × 10 mm i.d., 10 μm, Waters, Milford, MA, USA) coupled to a Waters 2998 photodiode array detector was used. Optical rotation data were measured by a Perkin-Elmer Model 341 polarimeter. CD spectra were recorded on a MODEL J-810-150S spectropolarimeter (MODEL J-810-150S, Tokyo, Japan). The silica gel GF254 used for TLC was supplied by the Qingdao Marine Chemical Factory (Qingdao, China). Spots were detected on TLC under UV light or by heating after spraying with 5% H2SO4 in EtOH. All solvent ratios are measured v/v.

3.2. Plant Material

The hypocotyl of B. gymmorrhiza was collected from Beilun, Guangxi Province, China, in May 2012. The specimen was identified by Professor Hangqing Fan from the Guangxi Mangrove Research Center, Guangxi Academy of Sciences. A voucher specimen (2012-GXAS-001) was deposited in the Guangxi Key Laboratory of Marine Environmental Science, Guangxi Academy of Sciences, China.

3.3. Extraction and Isolation

The hypocotyls of B. gymmorrhiza (25.4 kg) were exhaustively extracted with EtOH–CH2Cl2 (2:1, 30 L) at 25 °C for 4 days three times in a large metal bowl (diameter 80 cm, volume 50 L). The solvent was evaporated in vacuo (0.09 MPa, 40 °C, rotary evaporator) to afford a syrupy residue (435 g) that was suspended in distilled water (1.5 L) and extracted successively with petroleum ether (3 × 2 L), ethyl acetate (3 × 2 L) and n-butanol (3 × 2 L). The ethyl acetate portion (52.3 g) was subjected to column chromatography on silica gel, using CHCl3/Me2CO (from 10:0 to 5:4) and CHCl3/MeOH (from 10:1 to 0:10) as gradient eluents, giving twelve fractions (A−L). Fraction E was subjected to column chromatography on silica gel, using petroleum/ethyl acetate (from 10:0 to 0:10) as an eluent, giving six sub-fractions (E1−E6), then the sub-fraction E6 was separated by HPLC, using mixtures of MeOH/H2O (5:95) to yield 7 (4.1 mg, Rt = 27.0 min). Fraction F was separated by HPLC, using mixtures of MeOH/H2O (10:90) to yield 6 (1.6 mg, Rt = 18.7 min). Fraction G was separated by HPLC, using mixtures of MeOH/H2O (5:95) to yield 4 (1.2 mg, Rt = 19.0 min). The n-butanol soluble portion (171.4 g) was subjected to column chromatography on silica gel, using CHCl3/MeOH (from 10:0 to 0:10) as an eluent, giving fourteen fractions (An−Nn). Fraction Nn was subjected to a Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography with MeOH, then separated by HPLC, using mixtures of MeOH/H2O (5:95) to yield 5 (1.6 mg, Rt = 15.2 min), 1 (3.4 mg, Rt = 27.2 min), 2 (1.9 mg, Rt = 33.2 min) and 3 (3.7 mg, Rt = 48.3 min), respectively.

Menisdaurin B (1): Yellow powder; −44.7° (c 0.54, MeOH); CD (MeOH) Δε215nm−25.5; UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) nm: 271 (4.12); IR (KBr) νmax 3381 (OH), 2225 (CN), and 1621 (C=C) cm−1; 1H- (DMSO-d6) and 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6), see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 326.1238 (calcd for C15H21NO7 − H, 326.1240).

Menisdaurin C (2): Yellow powder; −56.2° (c 0.47, MeOH); CD (MeOH) Δε215nm−22.7; UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) nm: 267 (3.72); IR (KBr) νmax 3398 (OH), 2222 (CN), and 1620 (C=C) cm−1; 1H- (DMSO-d6) and 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6), see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 328.1394 (calcd for C15H23NO7 − H, 328.1396).

Menisdaurin D (3): Yellow powder; −76.2° (c 0.63, MeOH); CD (MeOH) Δε215nm−42.6; UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) nm: 270 (4.53); IR (KBr) νmax 3428 (OH), 2220 (CN), and 1623 (C=C) cm−1; 1H- (DMSO-d6) and 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6), see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 314.1238 (calcd for C14H21NO7 − H, 314.1240).

Menisdaurin E (4): Colorless plates; −47.3° (c 0.51, MeOH); CD (MeOH) Δε215nm−33.4; UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) nm: 269 (4.51); IR (KBr) νmax 3425 (OH) and 2219 (CN) cm−1; 1H (CD3OD) and 13C-NMR (CD3OD), see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 176.0679 (calcd for C8H11NO2 + Na, 176.0687).

3.4. Acid Hydrolysis of 1–3

Acid hydrolysis of 1−3 afforded glucose, which was identified in comparison with standard sugars as described in the literature [15,18,19]. Compounds 1−3 (1 mg each) were hydrolysed with 2 mol/L of HCl in H2O for 6 h at 85 °C. The reaction mixtures were concentrated. The reaction mixtures of 1−3 and the authentic D-glucose were subjected to TLC, using Me2CO/CH3CH(OH)CH3/H2O (26:14:7) as an eluent. The Rf values for the reaction mixtures of 1−3 (Rf for compounds 1−3 were 0.382, 0.383, and 0.382, respectively) were greatly similar to this of the authentic D-glucose (Rf = 0.384) under the same conditions.

3.5. Antiviral Assay

Antiviral activity and toxicity of 1−7 were assessed using a standardized culture assay [20], which uses cultures of the HBV-producing, human hepatoblastoma cell line [21]. This cell line, which chronically produces infectious HBV [22], has been shown to be an accurate and predictive model for all measured aspects of cellular HBV replication [23].

4. Conclusions

To our best knowledge, cyclohexylideneacetonitrile derivatives have been found in many sources [10,13,24,25,26,27,28], and some of molecules possessed prominent biological properties, such as anti-HBV [14], antioxidant [29], insecticidal [30], antifeedant [30], and antifungal [30] activities. In our work, four new cyclohexylideneacetonitrile derivatives, menisdaurins B–E (compounds 1–4), as well as three known cyclohexylideneacetonitrile derivatives, menisdaurin (5), coclauril (6), and menisdaurilide (7), were isolated from the hypocotyl of the mangrove B. gymnorrhiza. Compounds 1–7 showed moderate anti-HBV activities. Compounds 1–7 were isolated for the first time from B. gymnorrhiza, which enriches the class of cyclohexylideneacetonitrile molecules originated from marine resources.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31100260, 81260480), Guangxi Laboratory on Applied Techniques and Product Development of Beibu Gulf Marine Chinese Materia Medica (2013-8-2-16), the Project of Development of TCM Ph.D Degree, Guangxi University of Chinese Medicine (201410-02), Guangxi Key Laboratory on Generic Technology Research and Development of TCM Preparation (14-6-70), Guangxi Key Laboratory of Marine Environmental Science, Guangxi Academy of Sciences (GXKLHY13-06), the Foundation of Key Laboratory of Plant Resources Conservation and Sustainable Utilization, South China Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. 201210ZS), Guangxi Key Laboratory of Efficacy Study on Chinese Materia Medica (10-046-04), the Key Project of Science and Technology Department of Guangxi (No. 15104001-11).

Author Contributions

X.-X.Y. and J.-G.D. contributed in writing the manuscript. R.-M.H. conceived and designed the format of the manuscript. X.-T.H. and Y.X. were responsible for structure identification. H.-X.H. and Z.-C.D. were responsible for the isolation of the compounds. F.L. and C.-H.G. were in charge of the biological activity. E.-W.H. and Z.-P.W. were responsible for the analysis of the data of the biological activity.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are not available from the authors.

References

- 1.Homhual S., Zhang H.J., Bunyapraphatsara N., Kondratyuk T.P., Santarsiero B.D., Mesecar A.D., Herunsalee A., Chaukul W., Pezzuto J.M., Fong H.H. Bruguiesulfurol, a new sulfur compound from Bruguiera gymnorrhiza. Planta Med. 2006;72:255–260. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-873171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Homhual S., Bunyapraphatsara N., Kondratyuk T., Herunsalee A., Chaukul W., Pezzuto J.M., Fong H.H.S., Zhang H.J. Bioactive dammarane triterpenes from the mangrove plant Bruguiera gymnorrhiza. J. Nat. Prod. 2006;69:421–424. doi: 10.1021/np058112x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han L., Huang X.S., Sattler I., Dahse H.M., Fu H.Z., Lin W.H., Grabley S. New diterpenoids from the marine mangrove Bruguiera gymnorrhiza. J. Nat. Prod. 2004;67:1620–1623. doi: 10.1021/np040062t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han L., Huang X.S., Sattler I., Moellmann U., Fu H.Z., Lin W.H., Grabley S. New aromatic compounds from the marine mangrove Bruguiera gymnorrhiza. Planta Med. 2005;71:160–164. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-837784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun Y.Q., Guo Y.W. Gymnorrhizol, an unusual macrocyclic polydisulfide from the Chinese mangrove Bruguiera gymnorrhiza. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:5533–5535. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.05.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panyadee A., Sahakitpichan P., Ruchirawat S., Kanchanapoom T. 5-Methyl ether flavone glucosides from the leaves of Bruguiera gymnorrhiza. Phytochem. Lett. 2015;11:215–219. doi: 10.1016/j.phytol.2014.12.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao C.H., Yi X.X., Xie W.P., Chen Y.N., Xu M.B., Su Z.W., Yu L., Huang R.M. New antioxidative secondary metabolites from the fruits of a Beibu Gulf mangrove, Avicennia marina. Mar. Drugs. 2014;12:4353–4360. doi: 10.3390/md12084353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yi X.X., Chen Y., Xie W.P., Xu M.B., Chen Y.N., Gao C.H., Huang R.M. Four new jacaranone analogs from the fruits of a Beibu Gulf mangrove Avicennia marina. Mar. Drugs. 2014;12:2515–2525. doi: 10.3390/md12052515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ueda K., Yasutomi K., Mori I. Structure of a new cyanoglucoside from Ilex warburgii Loesn. Chem. Lett. 1983;1:149–150. doi: 10.1246/cl.1983.149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yogo M., Ishiguro S., Murata H., Furukawa H. Coclauril, a nonglucosidic 2-cyclohexen-1-ylideneacetonitrile, from Cocculus lauriforius DC. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1990;38:225–226. doi: 10.1248/cpb.38.225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi K., Matsuzawa S., Takani M. Studies on constituents of medicinal plants: 20. The constituent of vines of Menispermum dauricum DC. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1978;26:1677–1681. doi: 10.1248/cpb.26.1677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nahrstedt A., Wray V. Structural revision of a putative cyanogenic glucoside from Ilex aquifolium. Phytochemistry. 1990;29:3934–3936. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(90)85364-L. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakanishi T., Nishi M., Somekawa M., Murata H., Mizuno M., Iinuma M., Tanaka T., Murata J., Lang F.A., Inada A. Structures of new and known cyanoglucosides from a North-American plant, Purshia tridentata DC. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1994;42:2251–2255. doi: 10.1248/cpb.42.2251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geng C.A., Huang X.Y., Lei L.G., Zhang X.M., Chen J.J. Chemical constituents of Saniculiphyllum guangxiense. Chem. Biodivers. 2012;9:1508–1516. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201100270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka T., Ikeda T., Kaku N., Zhu X.H., Okawa M., Yokomizo K., Uyeda M., Nohara T. A new lignan glycoside and phenylethanoid glycosides from Strobilanthes cusia BREMEK. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2004;52:1242–1245. doi: 10.1248/cpb.52.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirk D.N. The chiroptical properties of carbonyl-compounds. Tetrahedron. 1986;42:777–818. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)87486-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burnett R.D., Kirk D.N. Chiroptical studies. 101. An empirical-analysis of circular-dichroism data for steroidal and related transoid α,β-unsaturated ketones. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1. 1981:1460–1468. doi: 10.1039/p19810001460. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prakash I., Chaturvedula V.S.P. Structures of some novel α-glucosyl diterpene glycosides from the glycosylation of steviol glycosides. Molecules. 2014;19:20280–20294. doi: 10.3390/molecules191220280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X.Y., Wang M.C., Xu M., Wang Y., Tang H.F., Sun X.L. Cytotoxic oleanane-type triterpenoid saponins from the rhizomes of Anemone rivularis var. flore-minore. Molecules. 2014;19:2121–2134. doi: 10.3390/molecules19022121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korba B.E., Gerin J.L. Use of a standardized cell-culture assay to assess activities of nucleoside analogs against Hepatitis B virus replication. Antivir. Res. 1992;19:55–70. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(92)90056-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sells M.A., Zelent A.Z., Shvartsman M., Acs G. Replicative intermediates of Hepatitis B virus in HepG2 cells that produce infectious virions. J. Virol. 1988;62:2836–2844. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.2836-2844.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Acs G., Sells M.A., Purcell R.H., Price P., Engle R., Shapiro M., Popper H. Hepatitis B virus produced by transfected HepG2 cells causes hepatitis in chimpanzees. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:4641–4644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.13.4641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korba B.E., Gerin J.L. Antisense oligonucleotides are effective inhibitors of Hepatitis B virus replication in vitro. Antivir. Res. 1995;28:225–242. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(95)00050-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seigler D.S., Pauli G.F., Frohlich R., Wegelius E., Nahrstedt A., Glander K.E., Ebinger J.E. Cyanogenic glycosides and menisdaurin from Guazuma ulmifolia, Ostrya virginiana, Tiquilia plicata, and Tiquilia canescens. Phytochemistry. 2005;66:1567–1580. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Damtoft S., Jensen S.R. Cyclohexyl butenolide glucosides from Epacridaceae. Phytochemistry. 1995;40:157–159. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(95)00181-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manga S.S.E., Messanga B.B., Sondengam B.L. 7,8-Dihydrobenzofuranones from Ouratea reticulata. Fitoterapia. 2001;72:706–708. doi: 10.1016/S0367-326X(01)00284-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sosa A., Winternitz F., Wylde R., Pavia A.A. Structure of a cyanoglucoside of Lithospermum purpureo-caeruleum. Phytochemistry. 1977;16:707–709. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)89236-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murakami A., Ohigashi H., Tanaka S., Hirota M., Irie R., Takeda N., Tatematsu A., Koshimizu K. Bitter cyanoglucosides from Lophira alata. Phytochemistry. 1993;32:1461–1466. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(93)85160-S. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silva T.M.S., Lins A.C.D., Sarmento-Filha M.J., Ramos C.S., Agra M.D., Camara C.A. Riachin, a new cyanoglucoside from Bauhinia pentandra and its antioxidant activity. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2013;49:685–690. doi: 10.1007/s10600-013-0707-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abbassy M.A., Abdelgaleil S.A.M., Belal A.S.H., Rasoul M.A.A.A. Insecticidal, antifeedant and antifungal activities of two glucosides isolated from the seeds of Simmondsia chinensis. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2007;26:345–350. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2007.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]