Abstract

Background:

All around the world, infertility, in many ways, is recognized as a stressful and a critical experience that can have impact on social and marital life of a couple. Infertility stress may affect the treatment and its outcome for such couples. The objective of the present study is to assess the predictors of high stress of infertility among married couples.

Materials and Methods:

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 120 couples (240 patients) who were diagnosed with primary and secondary infertility from June 2017 to June 2018. A psychological self-assessment questionnaire (Perceived Stress Scale-10) was used as a tool to evaluate the presence of high infertility stress among couples after obtaining their consent. Furthermore, other socioepidemiological data of patients were collected.

Statistical Analysis:

Data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 20). Univariate statistical analysis was used followed by multiple logistic regressions between high infertility stress and the predictor variables.

Results and Discussion:

The prevalence of high infertility stress was 53.3% among women and 40.8% among men. For women, multivariate analysis showed leading associations of high infertility stress with level of education, infertility type, infertility duration, and etiologies of infertility. However, for men, multivariate analysis showed leading associations between high infertility stress and alcohol status and inadequate sleep and infertility type.

KEYWORDS: Couples, diagnosis, infertility stress, predictors

INTRODUCTION

Everywhere in the world, having children is of a huge importance to individuals, couples, families, and societies. The prevalence of infertility is largely depending on the cultural and familial values.[1] In our country, most of the married couples wish to become parents because they believe that childbearing is important in the stability of any couple. Infertility is defined by the failure to achieve a natural pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected sexual intercourse.[2] Infertility is one of the most stressful experiences in a couple's life and a complex crisis causing a psychological threat and emotional pressure.[3] Infertility stress is specifically the thoughts and emotions related to infertility that the person tries to break free.[4] Mental health professionals refer to stress as “a dynamic condition in which an individual is confronted with an opportunity, constraint, or demand related to what he or she desires and for which the outcome is perceived to be both uncertain and important”.[5] According to the World Health Organization, the term primary infertility is used when a woman has never conceived and secondary infertility is the incapability to conceive in a couple who had at least one successful conception in the past.[6] It can negatively affect social, personal, and marital relationships, leading to divorce.[7] Worldwide, the prevalence of infertility affects 50–80 million couples at some point in their reproductive lives.[8] It is estimated to affect 10%–15% of all couples and, in almost half of such cases, a male factor is involved, but 15%–24% have unexplained etiology.[9,10]

To overcome this stress of infertility, assisted reproductive technology (ART) is considered the solution, and it is responsible for between 219,000 and 246,000 babies born each year worldwide.[11]

At the beginning of treatment, couples expect the treatment to be effective and hope that they will have a pregnancy.[12] Although these technologies have brought fresh hope to infertile couples, they have imposed great stress during diagnosis and longer periods of treatment.[13] Diagnosis of infertility, treatment failures, and implantation failures constitute unexpected and critical incidents that can overwhelm the individual's ability to respond adaptively. In addition, the application of these technologies had caused much emotional physical burden and much stress.[14,15] Women in emotional distress during treatment could not become pregnant.[16,17] Men's responses to infertility were similar to those of women only when their infertility was attributable to a male factor.[18] Sometimes, couples are very optimistic that the treatment would be a success for them, and sometimes they become pessimistic and feel that it does not work for them.[19] Unfortunately, in the majority of fertility centers, the medical components of infertility are often emphasized in spite of other psychological, spiritual, and sociocultural components, whereas they must be treated simultaneously.[20,21]

The more we understand the emotional and psychological barriers faced by patients in need of infertility treatment, the better we are able to help them to manage this process successfully.[22] To our knowledge, the prevalence and predictors of infertility stress in our country have not been studied so far, and hence the aim of this study was to assess the prevalence and predictors of high infertility stress among couples who were diagnosed for the first time at our public fertility center.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted at our fertility center. This institute which is part of the Ibn Sina hospital Center located in Rabat in Morocco, is the national reference center for ART where most of the cases of infertility are diagnosed and treated.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our Medicine Faculty. The sample included 120 couples attending our fertility center between June 2017 and June 2018. The nonprobability reasoned sampling technique was used to collect the data. Couples aged between 19 and 50 years, who were diagnosed for the first time at the center with primary and secondary infertility, and those who were consenting to participate were included in the study. The study excluded foreign couples and who are under treatment for psychopathology.

Sample size

Anticipating the prevalence of infertility stress in infertile couples as 50%, using the formula developed by Schwartz, the minimum number of participants required for this study[23] was observed to be 96 couples for a relative precision of 10% and 95% confidence level. The required sample size interested 120 couples (240 patients) who attended the Assisted Reproductive Health Center between June 2017 to June 2018.

Variables

The dependent variable was high infertility stress perceived. The independent variables under study were as follows: age, level of education, perceived income level, smoking status, alcohol status, inadequate sleep, sports activities, etiologies of infertility, duration of infertility, and infertility type.

Data collection

The consenting patients were interviewed for the first assessment on relevant socioepidemiological variables. The second assessment is a rating scale evaluation of the stress level-related infertility using the “Perceived Stress Scale-”-10. This adapted scale of Cohen and Williamson is one of the most used for assessing the perception of stress level.[24] It was the subject of various translations including the classical Arabic language.[25,26] It is composed of ten items and answer choices ranging from 0 to 4 for each item. The score is obtained by first reversing the scores of the positive items which are 4, 5, 7, and 8, where 4 = 0; 3 = 1; and 2 = 2. The total score is the sum of scores obtained from 0 to 40 points. The result will be indicated by the interpretation of the obtained score. The perceived stress is normal if total score obtained ranges of 0-10 points, it's weak of 11–20 points; moderate of 21–30 points; and high of 31–40 points.

In this study, the prevalence of high infertility stress among the participants' sample was an interesting factor, and therefore a score ≤30 has been coded “0,” which means “no high stress.” On the other hand, a score ≥31 has been coded “1,” indicating “existing high stress.” The duration of filling of the assessment requires between 3 and 5 min. Once the data were collected, the analysis was performed using SPSS (SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0, Released 2011, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp, USA) statistical software version 20.

The analysis of the quantitative data has been completed using frequency tables; univariate analysis followed by multivariate logistic regression to find the association between high infertility stress and predictor factors. All variables which were statistically significant on univariate analysis, at P < 0.20 levels, were included in the multivariate analysis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Procedure

A pretest of questionnaire for ten couples was first conducted to verify the feasibility of the research topic. For data collection, a report was built with the couples. Consent was obtained, and then the participants were informed to complete the assessment. All interviews were conducted by the searcher. The data were collected in a quiet room in the public fertility center; confidentiality was respected for the data collected. Finally, the data were connoted using the standardized connotation model of the test and coded by the researcher.

RESULTS

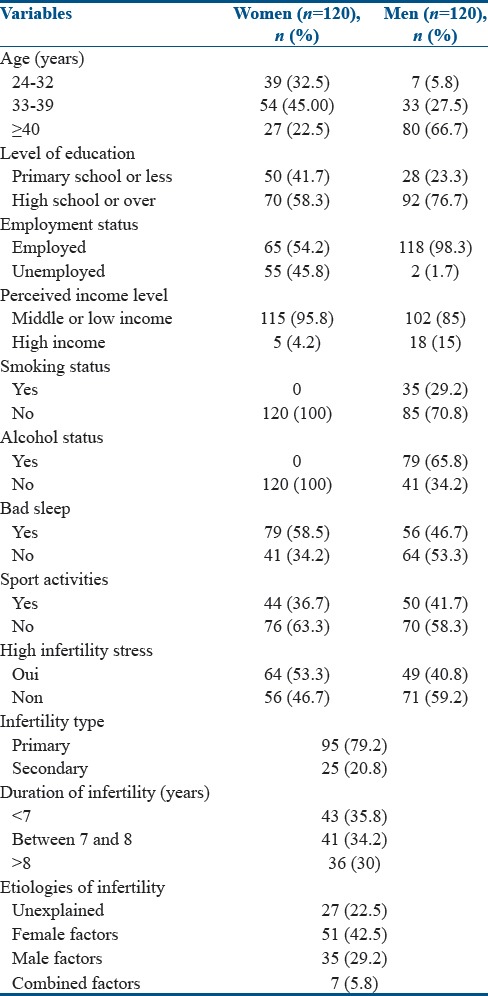

Table 1 shows the numbers and frequencies of the socioepidemiological variables. Out of the 120 couples diagnosed with infertility who participated in this study, most of the women (45%) were between <33 and 39 years old and most of the men (66.7%) belonged to an age range of ≥40 years with a mean age of 37.5 ± 5.16 years compared to 31.97 ± 4.104 years for women. Among all the respondents, 23.3% of men and 41.7% of women had a basic level of education. Furthermore, 58.3% of women and 76.7% of men had a high level of education. No cases of woman smokers or drinkers were detected in our sample, whereas 29.2% of men were smokers and 79 (65.8%) men were drinkers. The majority of respondents had a middle or low income (95.8% among women and 85% among men). Among participants with high perceived income levels, men represented (15%) compared to women (4.2%). The percentage of women who had inadequate sleep was (58.5%) compared to that of men (46.7%). As far as sports activities were concerned, the percentage of participants who do not practise sport is high, with 63.3% of women and 58.3% of men.

Table 1.

Summary of demographic and baseline characteristics

In each couple, wife and her husband had the same duration of infertility and the same type of infertility. The duration of infertility ranged from 3 to 22 years. The mean duration of infertility of the 120 couples is (7.55 ± 3.48). Forty-three couples (majority) had duration of infertility lower than 7 years (35.8%). In addition, primary infertility was the most dominant type, which occurred in 95 couples (79.2%), compared with 25 couples (20.8%) in secondary infertility. Analyzing the etiologies of infertility, 22.5% of the couples had unexplained factor, 42.5% were found to have female factor, 29.2% had male factor, and 5.8% of couples were known cases of combined factor.

Results showed that the prevalence of high infertility stress among patients was 53.3% of women and 40.8% of men [Table 1]. The results of univariate and multivariate analyses are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

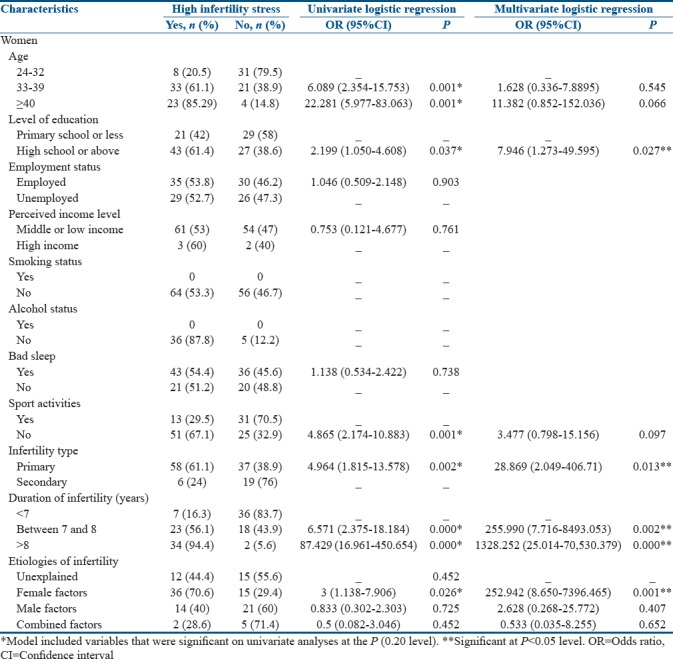

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis predictors for high infertility stress among women

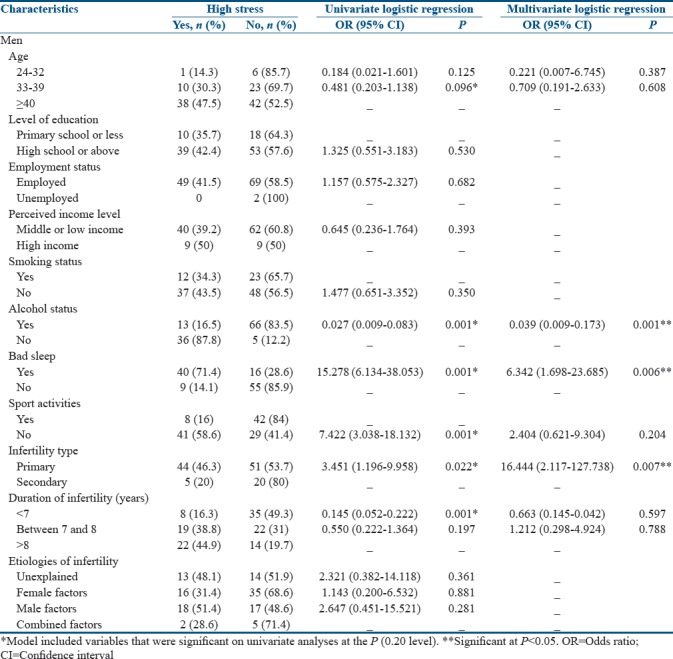

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis predictors for high infertility stress among men

Univariate analysis summarized in Table 2 illustrates that odds ratio (OR) of high infertility stress in women is predicted significantly by variables such as age range 33–39 years and ≥40 years and level of education for high school or higher. The sports activities were considered as a risk factor for high infertility stress. Other risk factors were also confirmed by the results of this study such as primary infertility and infertility duration concerning two classes of duration that (between 7 and 8 years) and (more than 8 years). Also, etiologies of infertility for female factor were considered as a risk factor for high infertility stress.

Multivariate analysis in women showed that only level of education, infertility type, duration of infertility, and etiologies of infertility were found significantly associated with high infertility stress. There is a low risk of high infertility stress occurring in women with primary school or less, (P = 0.027), however a high risk was observed in women with: (a) primary infertility (adjusted OR = 28.869, CI: 2.049-406.71, P = 0.013); (b) infertility duration ranged between 7 and 8 years (adjusted OR = 255.990, CI: 7.716-8493.053, P = 0.002); (c) infertility duration >8 years (Adjusted OR = 1328.252, CI: 25.014-70530.379, P < 0.001); and for women with female infertility factor (Adjusted OR = 252.942, CI: 8.650-7396.465, P = 0.001).

According to Table 3, univariate analysis in men showed that odds of high infertility stress were predicted significantly by many variables such as age range (33–39 years), alcohol status for drinkers, and duration of infertility (<7 years) which were found as protector factors, but bad sleep, sports activities, and infertility type were found as risk factors for high infertility stress. On the other hand, multivariate analysis in men showed that only alcohol status, bad sleep, and infertility type were observed significantly associated with high infertility stress. Alcohol status for drinkers was found as a protector factor for high infertility stress (adjusted OR = 0.039, CI: 0.009–0.173, P = 0.001), but high risk was observed in men who had inadequate sleep (adjusted OR = 6.342, CI: 1.698–23.685, P = 0.006) and who had a primary infertility (adjusted OR = 16.444, CI: 2.117–127.738, P = 0.007).

DISCUSSION

In our country, having children is very important for the stability of any couple. Expectations from society, family, and friends place the couple, especially the woman, in a very embarrassing situation. In this finding, the prevalence of high infertility stress indicated that women were found high stressed with infertility when diagnosed than men: 53.3% in women compared with 40.8% in men. This result is in agreement with studies conducted by Luk and Loke,[27] Dooley et al.,[28] and El Kissi et al.[29] who had showed that women reported more stress than men. Hence, there is a need for quality care through support and information and a greater awareness of society in this regard.

Our results showed that the education level of women was found to be significantly associated with high infertility stress. A great risk of high infertility stress was observed in women who had educational level of high school or higher. This result is in contrast with that of Yusuf's study conducted in Pakistan in 2016 who showed that level of education did not appear to have any positive effect on the stress score[30] and in contrast with Alhassan's findings conducted in Ghana in 2014 who showed higher rates of negative psychological symptoms in infertile women who had little or no formal education.[1] This finding could be explained first by the differences between sociocultural and economic contexts and second by the fact that in our modern society, women are more and more educated. Thus, the level of education and career of these women decrease the age of childbearing and as a result, women experience infertility problems by the end of their (30s). The sense of the brevity of time as a biological clock is approaching the end of the childbearing age, which can tire their relationship as a couple, and therefore increases stress and guilt in them.

Our study did not demonstrate any association between age, sports activities, and high infertility stress for both men and women. However, an association was found between infertility type and high infertility stress in both women and men, so high risk was observed in patients who had a primary infertility. This result concurs closely with the available data in the Karabulut's study conducted in Turkey in 2013, which showed that secondary infertility in comparison to primary infertility would seem to be a less stressful situation with less psychological consequences.[31] This is because the couple who has a child should have more hope for medical recovery and at least partial fulfillment of the paternity wish and a life that fits into socially acceptable norms.

In men, we did not find any association between duration of infertility and high infertility stress, but in women, our result revealed that women having a duration of infertility of 7 years or higher were more likely to have a high stress than women who had duration of infertility <7 years. This can be explained by the fact that women's desire to have children increases more and more as the duration of infertility increases and so the stress becomes higher. This finding is also consistent with previous studies conducted by Karabulut et al.[31] and Wiweko et al. conducted in Indonesia in 2016,[32] in which they showed that the longer the duration of infertility, the more we can expect an increasingly important psychological dysfunction caused by the loss of hope of becoming fertile and the high perceived stress generated by this situation. Furthermore, women who had female factor as etiology of infertility were more likely to be highly stressed than women who had other etiologies of infertility such as male factors, unexplained factors, and combined factors. This result concurs closely with the available data in many other studies such as Navid et al.'s study conducted in Iran in 2017 that showed that in couples diagnosed with female factor infertility, wives showed significantly more stress and depression than their husbands.[33] Furthermore, the same result was confirmed in a study conducted in India in 2015 by Patel et al. who showed that wives with diagnosed female factors such as etiology of infertility experienced higher stress in self-esteem than wives experiencing a diagnosed male factor.[34] In addition, our results could be explained by the fact that in our country, like other Muslim countries, marriage and reproduction are considered of utmost importance to any couple. Hence, the expectations of society, family, and friends place the couple, especially the woman, in a very embarrassing situation. Men are often placed under pressure for a second or multiple marriages because religion and culture allow men to have more than one wife at the same time. This situation negatively affects the psychological state of women and increases their stress.

An interesting finding of this study showed that alcohol consumption in men was found as a protector factor against the high infertility stress. This result was consistent with a research conducted by Rice and Van Arsdale in Florida in 2010 who had found that using alcohol to cope with stress is a common reason for drinking, even though our findings demonstrated this association.[35]

Finally, another result of this study showed that the significant risk of high stress was observed in men who had less sleep time compared to those men who had adequate sleep time. This finding is further corroborated with the study conducted by Jensen et al. in Denmark in 2013 which showed that sleep disturbances may be associated with psychological stress.[36] Also, it is in line with studies conducted by Durairajanayagam in Malaysia in 2018[37] and by Choi et al. in Korea in 2016 which showed that there might be an important link in the relation between stress and sleep.[38]

CONCLUSION

This study showed that the prevalence of high infertility stress is strongly present among couples in the diagnosis of their infertility, especially in women. In addition, this finding showed that the predictors of high infertility stress differ by sex and the identified predictors include level of education, quality of sleep, alcohol consumption, duration of infertility, etiologies of infertility, and infertility type. For a good management of infertility, we suggest that it will be necessary to use a holistic care, including information, support approaches by nurses, and psychosocial approaches when needed. Further research is needed to explore other predictors of stress in infertile patients, especially in relation to sociological and cultural aspects.

This study was not without limitations. It is a cross-sectional study which was a limitation and we used only 120 couples, which was a small number, who managed to move to access this more specialized reproductive care in our country.

Implications of these study results

The results of this study suggest that there is a dynamic and complex interaction between infertility stress and its preachers. Also, they have shown that the prevalence of infertility stress in our context is high among couples seeking assisted reproductive technology treatments. This finding helped us to better understand the extent of the difficult situation our clients are facing, and it requires us as health service providers to adopt a holistic approach to infertility care in our center, which will include: (a) specialized scientific nursing consultations to inform, educate, support, and accompany couples adequately throughout the treatment process and to help them manage this stress; (b) psychological/psychiatric consultations if necessary for at-risk couples who are about to experience a deterioration in their physical and mental health; and (c) interventions by social workers and community support groups specialized in this field to help infertile couples. This holistic approach will undoubtedly contribute to: (a) normalize the subject of infertility and reduce the levels of stress and inferiority often felt by this population; (b) encourage these couples to continue their treatment and adapt better; (c) develop practice, education, and research in the field of reproductive health; (d) raise awareness among managers and decision makers about the stress of infertility in order to improve the psychological health and socioeconomic situation of infertile couples; and (e) extend this approach to all fertility centers in the country from this national reference center.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to all patients and their families and all health professionals at the Assisted Reproductive Technology Center of the Reproductive Health Center of Rabat, Moracco.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alhassan A, Ziblim AR, Muntaka S. A survey on depression among infertile women in Ghana. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14:42. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-14-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gurunath S, Pandian Z, Anderson RA, Bhattacharya S. Defining infertility – A systematic review of prevalence studies. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17:575–88. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammerli K, Znoj H, Berger T. What are the issues confronting infertile women? A qualitative and quantitative approach. Qual Rep. 2010;15:766–82. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin YN. Counselling a Taiwanese woman with infertility problems. Couns Psychol Q. 2010;15:209–15. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robbins SP. Essentials of Organizational Behavior. 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mascarenhas MN, Flaxman SR, Boerma T, Vanderpoel S, Stevens GA. National, regional, and global trends in infertility prevalence since 1990: A systematic analysis of 277 health surveys. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baghiani Moghadam MH, Aminian AH, Abdoli AM, Seighal N, Falahzadeh H, Ghasemi N, et al. Evaluation of the general health of the infertile couples. Iran J Reprod Med. 2011;9:309–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO. Challenges in reproductive health research: Biennial report 1992-1993. Geneva: WHO; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sikka SC. Relative impact of oxidative stress on male reproductive function. Curr Med Chem. 2001;8:851–62. doi: 10.2174/0929867013373039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashraf DM, Ali D, Azadeh DM. Effect of infertility on the quality of life, a cross – Sectional study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:OC13–5. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8481.5063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Degtyareva V. Defining family in immigration law: Accounting for nontraditional families in citizenship by descent. Yale Law J. 2011;120:862–908. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boden J. When IVF treatment fails. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2007;10:93–8. doi: 10.1080/14647270601142614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Latifnejad Roudsari R, Rasoulzadeh Bidgoli M, Mousavifar N, Modarres Gharavi M. The effects of participatory consultations on perceived stress of infertile women undergoing IVF. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2011;14:22–31. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dancet EA, Van Empel IW, Rober P, Nelen WL, Kremer JA, D'Hooghe TM, et al. Patient-centred infertility care: A qualitative study to listen to the patient's voice. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:827–33. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Empel IW, Hermens RP, Akkermans RP, Hollander KW, Nelen WL, Kremer JA, et al. Organizational determinants of patient-centered fertility care: A multilevel analysis. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:513–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durgun-Ozan Y, Okumuş H. Experiences of Turkish women about infertility treatment: A qualitative study. Int J Basic Clin Stud. 2013;2:56–64. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benyamini Y, Gozlan M, Kokia E. Variability in the difficulties experienced by women undergoing infertility treatments. Fertil Steril. 2005;83:275–83. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nachtigall RD, Becker G, Wozny M. The effects of gender-specific diagnosis on men's and women's response to infertility. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:113–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Awtani M, Mathur K, Shah S, Banker M. Infertility stress in couples undergoing intrauterine insemination and in vitro fertilization treatments. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2017;10:221–5. doi: 10.4103/jhrs.JHRS_39_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allan H. A 'good enough' nurse: Supporting patients in a fertility unit. Nurs Inq. 2001;8:51–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1800.2001.00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menning BE. The emotional needs of infertile couples. Fertil Steril. 1980;34:313–9. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)45031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rich CW, Domar AD. Addressing the emotional barriers to access to reproductive care. Fertil Steril. 2016;105:1124–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartz D. Statistical Methods for physicians and biologists. Paris, France: Madrigall Group, Edition Flammarion Medecins Sciences; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen S, Williamson G. The Social Psychology of Health: Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology. In: Spacapam S, Oskamp S, editors. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reis RS, Hino AA, Añez CR. Perceived stress scale: Reliability and validity study in Brazil. J Health Psychol. 2010;15:107–14. doi: 10.1177/1359105309346343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaaya M, Osman H, Naassan G, Mahfoud Z. Validation of the Arabic version of the Cohen perceived stress scale (PSS-10) among pregnant and postpartum women. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:111. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luk BH, Loke AY. The impact of infertility on the psychological well-being, marital relationships, sexual relationships, and quality of life of couples: A systematic review. J Sex Marital Ther. 2015;41:610–25. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2014.958789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dooley M, Dineen T, Sarma K, Nolan A. The psychological impact of infertility and fertility treatment on the male partner. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2014;17:203–9. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2014.942390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El Kissi Y, Romdhane AB, Hidar S, Bannour S, Ayoubi Idrissi K, Khairi H, et al. General psychopathology, anxiety, depression and self-esteem in couples undergoing infertility treatment: A comparative study between men and women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;167:185–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yusuf L. Depression, anxiety and stress among female patients of infertility; A case control study. Pak J Med Sci. 2016;32:1340–3. doi: 10.12669/pjms.326.10828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karabulut A, Özkan S, Oğuz N. Predictors of fertility quality of life (FertiQoL) in infertile women: Analysis of confounding factors. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;170:193–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiweko B, Anggraheni U, Detri Elvira S, Putri Lubis H. Distribution of stress level among infertility patients. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2017;22:145–8. DOI:10.1016/j.mefs.2017.01.005. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Navid B, Mohammadi M, Vesali S, Mohajeri M, Omani Samani R. Correlation of the etiology of infertility with life satisfaction and mood disorders in couples who undergo assisted reproductive technologies. Int J Fertil Steril. 2017;11:205–10. doi: 10.22074/ijfs.2017.4658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patel A, Sharma PS, Narayan P, Binu VS, Dinesh N, Pai PJ, et al. Prevalence and predictors of infertility-specific stress in women diagnosed with primary infertility: A clinic-based study. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2016;9:28–34. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.178630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rice KG, Van Arsdale AC. Perfectionism, perceived stress, drinking to cope, and alcohol-related problems among college students. Univ Fla J Couns Psychol. 2010;57:439–50. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jensen TK, Andersson AM, Skakkebæk NE, Joensen UN, Blomberg Jensen M, Lassen TH, et al. Association of sleep disturbances with reduced semen quality: A cross-sectional study among 953 healthy young Danish men. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:1027–37. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Durairajanayagam D. Lifestyle causes of male infertility. Arab J Urol. 2018;16:10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.aju.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi JH, Lee SH, Bae JH, Shim JS, Park HS, Kim YS, et al. Effect of sleep deprivation on the male reproductive system in rats. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31:1624–30. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.10.1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]