Abstract

Background:

Follicular involvement of lentigo maligna (LM) is considered a histopathologic hallmark, but its prevalence and characteristics have not been well-defined. The depth of intrafollicular extension by neoplastic melanocytes may have clinical importance in the treatment of lentigo maligna.

Objective:

To describe the prevalence and features of follicular involvement in LM, including depth of follicular growth by melanocytes.

Methods & Materials:

Single-center retrospective study of 100 consecutive cases of surgically excised LM treated from 2013 to 2015. Slide review for cases with residual LM on debulk specimen was performed by a dermatologic surgeon and dermatopathologist to characterize follicular involvement.

Results:

Seventy-two of 100 specimens met inclusion criteria for histopathologic evaluation. Follicular involvement was seen in 95.8% of specimens (95% CI: 88.3%−99.1%), with a mean 68% of follicles involved in a single specimen. The mean depth of intrafollicular growth by lesional melanocytes was 0.45 mm (SD=0.23, range 0.1 mm to 1.1 mm). Tumor cells were confined to the infundibular portion of the hair follicle in 60.9% of specimens.

Conclusion:

Superficial follicular involvement is a ubiquitous finding in LM. When considering treatment options for LM with a depth-dependent modality aiming for tumor clearance, mean and maximum depths of involvement should be considered.

Introduction

Lentigo maligna (LM) and lentigo maligna melanoma (LMM) are subtypes of melanoma in situ and melanoma, respectively, occurring typically in elderly individuals on sun-damaged skin, most commonly on head and neck locations.(1) Surgical excision, whether staged local excision, or Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), is generally the preferred choice of treatment.(2) However, non-surgical treatment modalities such as off-label imiquimod or radiation may be used at the provider’s discretion based on patient age, coexisting medical comorbidities, lesion size, and location, and patient preference after discussion of risks and benefits.(2–8)

Standard guidelines for melanoma histopathologic reporting exist; however, the presence, absence, and extent of follicular involvement is usually not recorded subtype.(9) Supplemental diagnostic modalities such as dermoscopy and reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) are increasingly utilized and have suggested follicular involvement as one means of distinguishing LM from benign facial pigmented lesions.(10–12) Most importantly, however, follicular involvement, particularly the depth of atypical melanocytes extending along adnexa, may have clinical significance in LM treatment. The depth of atypical adnexal melanocytes likely impacts the efficacy of tissue-sparing surgeries in these cosmetically and functionally important areas as well as depth-dependent therapies such as radiation and topical agents where epidermal penetration is limited. Follicular involvement by melanoma in situ may also account for some cases of locally persistent lentigo maligna after surgery. If neoplastic melanocytes are located deep within a follicular unit and the surgical excision transects such follicles, which may be overlooked during margin assessment, this increases the risk for local recurrence.

The tumor cells of melanomas in the head and neck region have been shown to extend much deeper when compared to other anatomic locations.(13) A higher recurrence rate for LM after non-surgical treatment on the nose has been reported when compared to other facial locations such as the cheek.(3) Greveling et al. studied the histologic parameters of their recurrences and identified that the nose had a significantly higher density of pilosebaceous units (PSU) when compared to the cheek, as well as a significantly greater maximum depth of the PSU.(3) This included a comparative greater depth of extension of the atypical melanocytes along the PSU. This data suggests that not only is anatomic location a key consideration for LM treatment and recurrence, but perhaps the primary reason behind the anatomic differences lies in the depth and density of the follicular units. This may have a profound treatment implication as a higher PSU density may harbor a greater collection of neoplastic melanocytes in deeper portions of the appendages.

The aim of our study is: (1) to characterize the incidence of follicular involvement in LM, and (2) to define the extent of follicular involvement seen, including the depth of lesional melanocytes.

Methods

This was a single-center retrospective study. Institutional Review Board (IRB) exemption was obtained. The first 100 consecutive patients who underwent staged excision for biopsy-proven lentigo maligna at our institution from 2013 to 2015 were reviewed.(14, 15)

Pathology reports for each patient were reviewed. For all patients with residual LM on the tumor debulking specimen noted in the pathology report, slides were pulled and examined by a board-certified dermatopathologist and fellowship-trained Mohs surgeon. Cases with > 75% of the specimen with scar from biopsy obliterating adnexal structures and those with invasive or microinvasive disease were excluded from evaluation to limit cases to melanoma in situ, as invasive melanoma may have different tendencies for follicular involvement. One case was excluded due to reactive changes complicating the histologic interpretation, and 1 outside case was excluded due to inability to obtain the biopsy slides for review and confirmation. A total of 72 cases remained for analysis. The most representative section with complete epidermis was used from each glass slide for analysis. Lesion location, follicular involvement, percentage of residual in situ disease, and the degree of scar noted (none, minimal, moderate, severe) were recorded.

Follicular involvement was defined as atypical melanocytes that were microscopically judged to be part of the lentigo maligna melanoma in situ present in follicular epithelium, typically at the infundibular stromal junction. It was further characterized as percentage of follicles involved, deepest involvement along the follicle in millimeters (distance from the surface of the follicular ostium to the most deeply located intrafollicular neoplastic melanocyte), and the deepest anatomic portion of the follicle involved.

Descriptive statistics and graphical methods were used to describe the surgical and histologic characteristics of these lentigo maligna. Ninety percent exact binomial confidence intervals were used to provide a range of prevalence estimates for follicular involvement based on our sample size. Of the 72 samples in the dataset, 69 exhibited follicular involvement. These 69 lesions were evaluated for depth of involvement, and deepest involvement along the follicle. Linear regression was used to assess the any differences in depth of involvement and deepest involvement by anatomic site of the surgical procedure. All analyses were performed with Stata v.14.2, Stata Corporation, College Station, TX.

Results

Seventy-two of 100 total pathology specimens met inclusion criteria of melanoma in situ with residual tumor present on debulking tissue. Tumor location was the cheek in the majority of cases (29), followed by the forehead (9), scalp (9), and nose (8). There were 4 cases on the ear, and 3 cases on the eyelid. There were 2 cases each involving the chin, lip, and neck, followed by 1 case each involving the eyebrow, glabella, temple, and leg.

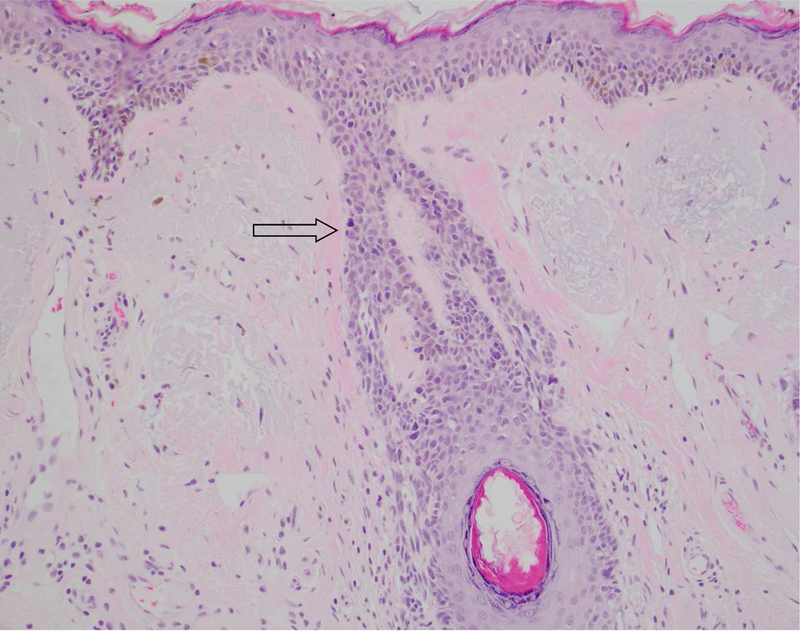

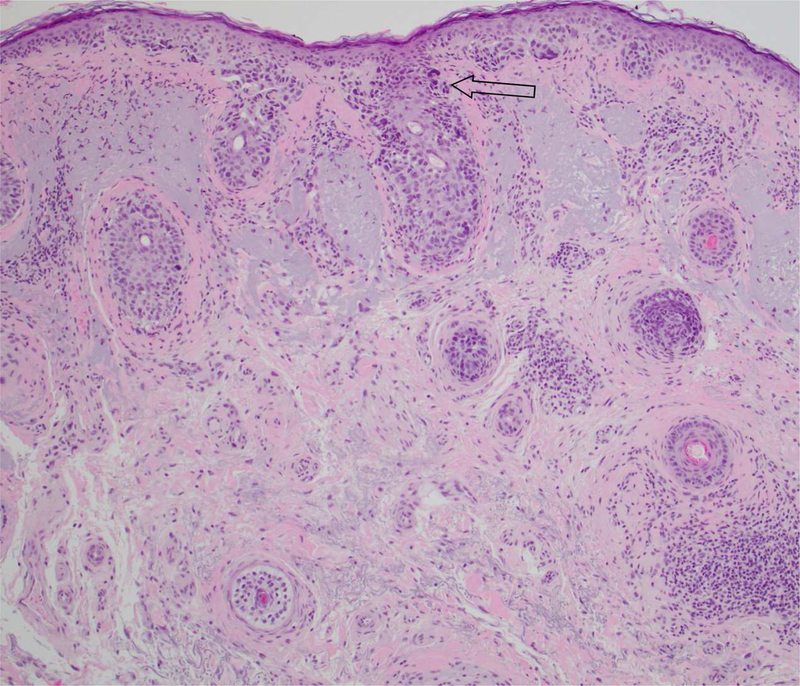

Slide review revealed follicular involvement in 69/72 specimens (95.8%, 95% CI: 88.3%−99.1%). Figure 1a and 1b show typical cases of follicular involvement. The mean percentage of follicles involved in a single histologic section was 68.4% (SD=24.3%). The mean depth of atypical melanocyte extension within the adnexa was 0.45 mm (SD=0.23, range 0.1 mm to 1.1 mm), corresponding to infundibular involvement in 42/69 (60.9%, 95% CI:48.4%−72.4%) specimens. Seven of 69 specimens (10.1%, 95% CI 4.1%−19.8%) demonstrated atypical melanocytes reaching the sebaceous duct, and 19/69 (28%, 95% CI:17.4%−39.6%) of cases showed involvement of the sebaceous lobule. One case extended to the level of the eccrine glands (1%), with a maximum depth of 1.1 mm.

Figure 1.

A, Lentigo maligna melanoma in situ with follicular involvement. An increased density of solitary units of melanocytes with nuclear atypia is seen at the dermoepidermal follicular dermal junction (arrow)

B, Lentigo maligna melanoma in situ with follicular involvement. Nests and solitary units of melanocytes are present at the dermoepidermal and follicular infundibular stromal junction.

(A-B Hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnification: 10x objective)

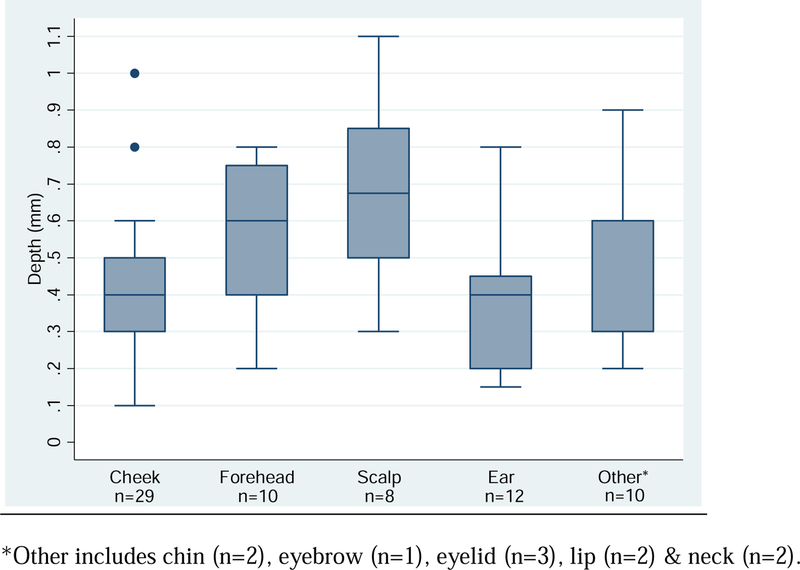

Anatomic site-specific differences were observed for deepest involvement along the follicle. Figure 2 presents boxplots of depth by anatomic location. Compared to lesions on the cheek, with an average depth of 0.41mm (SD=0.20), lesions on the forehead (depth = 0.57mm, SD=0.21) and scalp (depth = 0.68mm, SD=0.26) were significantly deeper, p-values of 0.05 and 0.002, respectively. No significant differences in depth were observed between cheek lesions and lesions on the ear or other combined anatomic locations (chin, eyebrow, eyelid & neck).

Figure 2.

Boxplot of follicular depth by anatomic site (n=69).

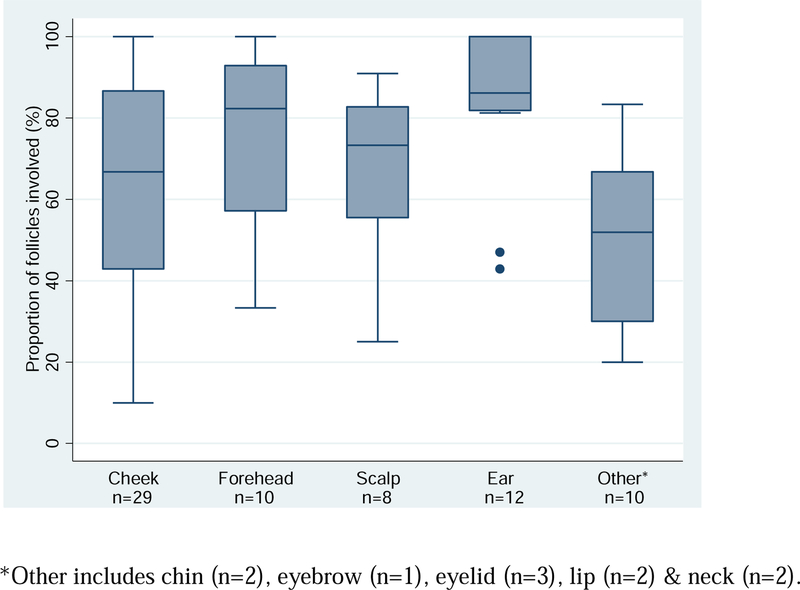

The average percent of follicles involved for each specimen was 68.3% (SD=24.3%). Figure 3 presents the distribution of the percent follicles involved by anatomic site of the surgical procedure. Compared to lesions on the cheek, with an average percent involvement of 65.4%, only lesions on the ear (percent involvement = 83.2%) showed significant difference, p-value = 0.03. All other sites, forehead (percent involvement = 77.0%), scalp (percent involvement = 67.3%), and other combined anatomic locations (chin, eyebrow, eyelid & neck), showed no statistical difference.

Figure 3.

Boxplot of proportion of follicles involved per lesion by anatomic site (n=69).

Discussion

Follicular involvement by lentigo maligna is a common phenomenon and its extent is relevant for treatment. In this study, we systematically examined cases from staged excision specimens with two independent readers to better quantify the presence of atypical melanocytes within distinct anatomic regions of the hair follicle. We demonstrated that 95.8% of all LM debulking specimens contained atypical melanocytes involving follicular units. Furthermore, a majority of follicles in each section had some degree of involvement, indicating a high frequency of occurrence even within each specimen. This is consistent with prior reports highlighting follicular involvement as a hallmark for the LM subtype. However, despite the ubiquity of follicular involvement, it is under recognized and deep follicular extension is not routinely documented in pathology reports of LM. Clinical providers must be aware that the lack of reporting does not exclude the existence of follicular involvement; rather follicular extension should be assumed in cases of LM based on our findings and prior studies.

With comparable results, another study analyzed 100 cases of primary cutaneous melanomas of various histologic subtypes and revealed 82% of cases of melanoma in situ (MIS) possessed tumor cells within one or more hair follicles, 69.5% of cases limited to the follicular infundibulum.(13) Extension of tumor cells to the isthmus occurred in 29.3% of cases with only 1 case (1%) demonstrating tumor cells beneath the hair follicle bulge. Pozdnyakova et al included LM as well as superficial spreading subtypes, each of which had cases of follicular involvement as well as follicular sparing. Of note, 97% of their LM cases showed some degree of follicular involvement, along with 97.2% of cases on the head and neck compared to non-head and neck regions which only showed 73.4% involvement. Tumors of the head and neck demonstrated a greater tendency to extend deeper compared to non-head and neck tumors. The face is known to have a higher density of PSUs(16) with certain facial regions demonstrating more deeply located PSUs as well,(3) which may offer an explanation for the deeper tumor extension of the head and neck. Pozdnyakova et al. did not observe any differences in involvement between types of follicles (large terminal and small vellus) or stage of development of the hair follicle.(13)

The diagnosis of LM and LMM relies on a multitude of histologic features, and it is important to recognize that follicular involvement alone does not confirm the diagnosis. The presence of superficial follicular involvement has been noted in normal, yet sun-damaged skin,(17) as well as other types of melanoma such as the rare variant follicular melanoma,(1, 18, 19) and folliculotropic metastases of melanoma.(18) However, we advocate that the overall importance of follicular involvement within a confirmed diagnosis of LM should not be underestimated, as it may ultimately impact treatment success.

The density and depth of follicular involvement in LM is pertinent when considering various treatment options. In our study, the infundibulum was the most common region of involvement, with the average depth of atypical melanocyte extension along adnexae of 0.45 mm. However, there were cases of deeper extension, with a maximum reported depth up to 1.1 mm, corresponding to the level of the eccrine glands. Tissue-sparing surgical modalities, while the gold standard of care, are likely to have higher rates of recurrence if the depth of surgery is not sufficient to remove the entire follicular unit. For instance, on more cosmetically sensitive regions such as the ear and nose, follicles are commonly transected in the interest of tissue sparing. Radiation therapy, which is highly depth-dependent, has been less effective at minimizing in-field recurrences with more superficially-directed treatment.(20) One large review recommends a treatment depth of at least 5 mm to achieve adequate clearance as their group identified follicles extending as deep as 4.5 mm in some regions.(20) The presence of extensive follicular involvement may explain why laser and light therapies are not effective, as the depth of penetration is limited. For example, the erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Er:YAG; 2940 nm) laser removes approximately 15–25 um per pass and the carbon dioxide (CO2; 10600 nm) laser approximately 100–150 um per pass; therefore numerous passes would be required to reach an adequate depth, and the risk of scarring or dyspigmentation may increase.(21, 22) The depth of penetration of topical agents rarely exceeds the epidermis. It is unclear if immune response modifiers such as imiquimod can herald an adequate inflammatory response substantially beyond the depth of penetration. However, it is well known that the hair follicle is an immune-privileged site, which may hold potential implications in the efficacy of imiquimod or other immune-modifying therapies in regions with concentrated PSUs.(23) Combination therapies have been proposed to increase depth of topical penetration though treatment success remains inferior to surgical modalities.(3, 24)

A few conflicting studies on follicular involvement in LM do exist within the literature. One study did not find statistical significance of follicular depth or involvement as prognostic indicators for LM recurrence post-imiquimod monotherapy, despite 78.2% occurrence of follicular involvement.(25) However, they did note significant risk of recurrence with an increased total number of melanocytes per millimeter, confirming a role for melanocyte density. Increased melanocyte density has been correlated in other studies with increased numbers of PSU.(3) Powell et al., observed a correlation between the presence of adnexal spread and a positive response to imiquimod therapy, which is difficult to explain as one would expect the opposite to be true.(26) This ambiguity heralds the need for further investigation into the presence, extent, and implications of follicular involvement in LM.

Conclusion

Follicular involvement in LM is very prevalent. The presence and depth of follicular involvement may have clinical implications for depth-dependent treatment modalities such as tissue-sparing surgery, radiation, and topical therapy. Extension of melanoma in situ into deeper portions of the follicles should be documented in pathology reports.

Capsule Summary.

Follicular involvement is a characteristic of lentigo maligna (LM) with unknown frequency.

95.8% of LM specimens demonstrated intrafollicular lesional melanocytes, with a mean depth of 0.45mm.

When managing LM, follicular involvement should be assumed.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: None Declared

This research was previously presented as a poster at the Annual American College of Mohs Surgery Meeting in April 2017

This research was granted an IRB waiver through the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center IRB.

References

- 1.Hantschke M, Mentzel T, Kutzner H. Follicular malignant melanoma: a variant of melanoma to be distinguished from lentigo maligna melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol 2004;26:359–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLeod M, Choudhary S, Giannakakis G, Nouri K. Surgical treatments for lentigo maligna: a review. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al. ] 2011;37:1210–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greveling K, van der Klok T, van Doorn MB, Noordhoek Hegt V, et al. Lentigo maligna - anatomic location as a potential risk factor for recurrences after non-surgical treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017;31:450–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greveling K, de Vries K, van Doorn MB, Prens EP. A two-stage treatment of lentigo maligna using ablative laser therapy followed by imiquimod: excellent cosmesis, but frequent recurrences on the nose. Br J Dermatol 2016;174:1134–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bichakjian CK, Halpern AC, Johnson TM, Foote Hood A, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of primary cutaneous melanoma. American Academy of Dermatology . J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;65:1032–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garbe C, Peris K, Hauschild A, Saiag P, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of melanoma. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline--Update 2012. European journal of cancer 2012;48:2375–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ng E, Levine V Role of Topical Therapy: Imiquimod. In: Nehal KS, Busam KJ, editor. Lentigo Maligna Melanoma New York: Springer; 2017. p. 139–51. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barker CA. Role of Radiation. In: Nehal KS, Busam KJ, editor. Lentigo Maligna Melanoma New York: Springer; 2017. p. 153–66. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma of the skin New York: Springer International Publishing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomez-Martin I, Moreno S, Andrades-Lopez E, Hernandez-Munoz I, et al. Histopathologic and Immunohistochemical Correlates of Confocal Descriptors in Pigmented Facial Macules on Photodamaged Skin. JAMA dermatology 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Menge TD, Hibler BP, Cordova MA, Nehal KS, et al. Concordance of handheld reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) with histopathology in the diagnosis of lentigo maligna (LM): A prospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016;74:1114–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schiffner R, Schiffner-Rohe J, Vogt T, Landthaler M, et al. Improvement of early recognition of lentigo maligna using dermatoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;42:25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pozdnyakova O, Grossman J, Barbagallo B, Lyle S. The hair follicle barrier to involvement by malignant melanoma. Cancer 2009;115:1267–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGuire LK, Disa JJ, Lee EH, Busam KJ, et al. Melanoma of the lentigo maligna subtype: diagnostic challenges and current treatment paradigms. Plastic and reconstructive surgery 2012;129:288e–99e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hazan C, Dusza SW, Delgado R, Busam KJ, et al. Staged excision for lentigo maligna and lentigo maligna melanoma: A retrospective analysis of 117 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;58:142–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pagnoni A, Kligman AM, el Gammal S, Stoudemayer T. Determination of density of follicles on various regions of the face by cyanoacrylate biopsy: correlation with sebum output . Br J Dermatol 1994;131:862–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hendi A, Wada DA, Jacobs MA, Crook JE, et al. Melanocytes in nonlesional sun-exposed skin: a multicenter comparative study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;65:1186–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Machan S, El Shabrawi-Caelen L, Nikolay E, Kerl H, et al. Follicular malignant melanoma: primary follicular or folliculotropic? Am J Dermatopathol 2015;37:15–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chapman I, Horton S, Liu W. Follicular Malignant Melanoma: A Rare Morphologic Variant of Melanoma. Report of a Case and Review of the Literature. Am J Dermatopathol 2017;39:e69–e70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fogarty GB, Hong A, Scolyer RA, Lin E, et al. Radiotherapy for lentigo maligna: a literature review and recommendations for treatment. Br J Dermatol 2014;170:52–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ross EV, Naseef GS, McKinlay JR, Barnette DJ, et al. Comparison of carbon dioxide laser, erbium:YAG laser, dermabrasion, and dermatome: a study of thermal damage, wound contraction, and wound healing in a live pig model: implications for skin resurfacing. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;42:92–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinstein C Computerized scanning erbium:YAG laser for skin resurfacing. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al. ] 1998;24:83–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christoph T, Muller-Rover S, Audring H, Tobin DJ, et al. The human hair follicle immune system: cellular composition and immune privilege. Br J Dermatol 2000;142:862–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hyde MA, Hadley ML, Tristani-Firouzi P, Goldgar D, et al. A randomized trial of the off-label use of imiquimod, 5%, cream with vs without tazarotene, 0.1%, gel for the treatment of lentigo maligna, followed by conservative staged excisions. Arch Dermatol 2012;148:592–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gautschi M, Oberholzer PA, Baumgartner M, Gadaldi K, et al. Prognostic markers in lentigo maligna patients treated with imiquimod cream: A long-term follow-up study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016;74:81–87 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Powell AM, Robson AM, Russell-Jones R, Barlow RJ. Imiquimod and lentigo maligna: a search for prognostic features in a clinicopathological study with long-term follow-up. Br J Dermatol 2009;160:994–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]