Abstract

The superior colliculus (SC) is a major site of sensorimotor integration in which sensory inputs are processed to initiate appropriate motor responses. Projections from the primary visual cortex (V1) to the SC have been shown to exert a substantial influence on visually-induced behavior, including “freezing”. However, it is unclear how V1 corticotectal terminals affect SC circuits to mediate these effects. To investigate this, we used anatomical and optogenetic techniques to examine the synaptic properties of V1 corticotectal terminals. Electron microscopy revealed that V1 corticotectal terminals labeled by anterograde transport primarily synapse (93%) on dendrites that do not contain gamma amino butyric acid (GABA). This preference was confirmed using optogenetic techniques to photoactivate V1 corticotectal terminals in slices of the SC maintained in vitro. In a mouse line in which GABAergic SC interneurons express green fluorescent protein (GFP), few GFP-labeled cells (11%) responded to activation of corticotectal terminals. In contrast, 67% of nonGABAergic cells responded to activation of V1 corticotectal terminals. Biocytin-labeling of recorded neurons revealed that wide-field vertical (WFV) and non-WFV cells were activated by V1 corticotectal inputs. However, WFV cells were activated in the most uniform manner; 85% of these cells responded with excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) that maintained stable amplitudes when activated with light trains at 1–20HZ. In contrast, in the majority of non-WFV cells, the amplitude of evoked EPSPs varied across trials. Our results suggest that V1 corticotectal projections may initiate freezing behavior via uniform activation of the WFV cells, which project to the pulvinar nucleus.

Keywords: superior colliculus, synapse, widefield vertical, electron microscopy, excitatory postsynaptic potential, GABA, GAD67, channelrhodopsin, RRID:AB_10015246, RRID:AB_91337, RRID:AB_477652, RRID: nif-000-30467

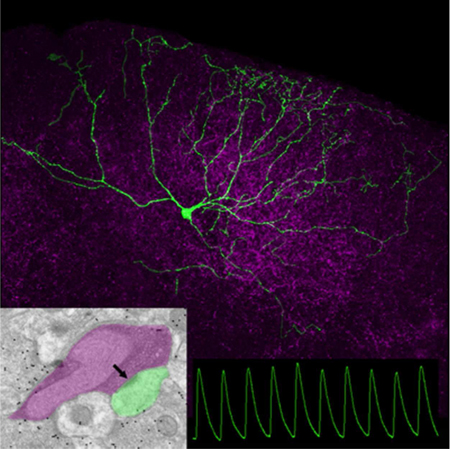

Graphical Abstract Legend

Electron microscopy revealed that the majority of corticotectal terminals (purple overlay) contact (arrow) small nonGABAergic dendrites (green overlay). Excitatory postsynaptic responses (green traces) to optogenetic activation of corticotectal terminals (purple) were recorded in vitro in a variety of cell types; wide field vertical cells (green neuron) displayed the most uniform responses.

Introduction

The superior colliculus (SC) is a major site of sensorimotor integration in which sensory inputs are processed to initiate appropriate motor responses. The superficial layers of the SC (the stratum griseum superficiale or SGS, and stratum opticum, or SO) receive dense inputs from both the retina and the primary visual cortex (V1), and these inputs interact with SC circuits to elicit apt behaviors (for review see Basso and May, 2017). While many of the receptive field properties of superficial SC neurons, such as direction selectivity, are directly inherited from their retinal afferents (Shi et al., 2017), corticotectal inputs have been shown to exert a substantial influence on the ultimate output of the SC, and the initiation of visually-induced behavior. For example, optogenetic silencing of V1 corticotectal inputs reduces the gain of collicular responses to looming visual stimuli that mimic approaching objects (Zhao et al., 2014), and blocks behavioral arrest (“freezing”) triggered by sudden flashes of light (Liang et al., 2015). Furthermore, optogenetic activation of V1 corticotectal inputs can induce freezing behavior, even in the absence of visual triggers (Liang et al., 2015).

A key pathway for the initiation of freezing behavior is a projection from the superficial SC to neurons within the lateral posterior (pulvinar) nucleus that project to the cortex, striatum and amygdala (Wei et al., 2015; Zingg et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2018). SC projections to the pulvinar nucleus arise from a unique class of cells known as wide field vertical cells (WFV; Zhou et al., 2017). These glutamatergic cells have very large dendritic fields that extend vertically to the dorsal surface of the SC. WFV cells have been shown to respond best to small spots moving across the visual field, but also respond to approaching objects (Wu et al., 2005; Gale and Murphy, 2016).

Transynaptic viral labeling techniques have revealed that V1 corticotectal terminals directly innervate WFV cells, but additionally innervate other projection neurons subtypes, as well as intrinsic GABAergic interneurons within the superficial SC (Zingg et al., 2017). Do these V1 corticotectal connections provide an indiscriminate gain control of all superficial SC cell types, or do corticotectal connections most effectively activate WFV cells? To address this question, we examined the synaptic properties of corticotectal terminals that originate from V1 using anatomical techniques to examine the ultrastructure of their postsynaptic targets, and in vitro optogenetic techniques to examine the postsynaptic responses elicited in various SC cell types, including WFV cells.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All breeding and experimental procedures were approved by the University of Louisville Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees. Experiments were carried out using mice, of either sex, of a C57BL/6J (Jax Stock No: 000664), or a line in which neurons that contain the 67KD isoform of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD67) express green fluorescent protein (GFP; Jax Stock No: 007677, G42 line)

Biotinylated dextran amine (BDA) injections

To label corticotectal axon projections via anterograde transport, C57BL/6J or GAD67-GFP adult mice were deeply anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (100–150 mg/kg) and xylazine (10–15 mg/kg). The analgesic meloxicam (1–2 mg/kg) was also injected prior to surgery. The animals were then placed in a stereotaxic apparatus (Angle Two Stereotaxic, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). An incision was made along the scalp, and a small hole was drilled in the skull. A glass pipette (20–40 μm tip diameter) containing a 5% solution of biotinylated dextran amine (BDA, Molecular Probes) in saline was lowered into V1 (3.8 mm caudal to Bregma, and 0.5 mm from the cortical surface) and BDA was iontophoretically ejected using 3 μA continuous positive current for 20 minutes. After removal of the pipette, the scalp skin was sealed with tissue adhesive (n-butyl cyanoacrylate), lidocaine was applied to the wound, and the animals were placed on a heating pad until mobile. Post-surgery, animals were carefully monitored for proper wound healing, and oral meloxicam (1–2 mg/kg) was administered for 48 h.

AAV injections

To label and activate corticotectal projections, an adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotype 2/1 carrying a vector for the Channelrhodopsin variant Chimera EF with I170 mutation (ChIEF) fused to the red fluorescent protein, tdTomato (production details in Jurgens et al., 2012) was injected unilaterally or bilaterally into V1 (3.8 mm caudal to Bregma, and 0.5 mm from the cortical surface). For virus delivery, P22–60 C57BL/6J or GAD67-GFP mice were deeply anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine and xylazine as described above. An incision was made along the scalp, and a small hole created in the skull above the left and/or right V1. Virus was delivered via a 34-gauge needle attached to a Nanofil syringe inserted in an ultramicropump. A volume of 75–200 nl was injected at each site at a rate of 20nl/minute.

Slice preparation and optogenetic stimulation

Eight to 12 days following virus injections, mice were deeply anesthetized with avertin (0.5mg/kg). Mice used for slice preparation ranged in age from P29-P37 (average age P31). Mice were either directly decapitated or transcardinally perfused with cold (4°C), oxygenated (95%O2/5%CO2) slicing solution containing the following (in mM): 2.5 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 10 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 234 sucrose, and 11 glucose, before rapid decapitation (in mice older than P35). The brain was removed from the head, chilled in the cold slicing solution described above for 2 mins, and was quickly transferred into a petri dish with room temperature slicing solution to block the brain for subsequent sectioning. Coronal slices (300μm) were cut in room temperature slicing solution using a vibratome (Leica VT1000 S). Then slices were transferred into an incubation solution of oxygenated (95%O2/5%CO2) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (in mM): 126 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, and 10 glucose at 32°C for 30 mins, and later maintained at room temperature.

Individual slices were transferred into a recording chamber, which was maintained at 32°C by an inline heater and continuously perfused with room temperature oxygenated ACSF (2.5ml/min, 95%O2/5%CO2). Slices were stabilized by a slice anchor or harp (Warner Instruments 64–0252). Neurons were visualized on an upright microscope (Olympus BX51WI) equipped with both differential interference contrast optics and filter sets for visualizing CTB-488 and YFP (Chroma 49002) or tdTomato (Chroma 49005) using a 4x or 60x water-immersion objective (Olympus) and a CCD camera. Recording electrodes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries (World Precision Instrument Inc.) by using a MODEL P-97 puller (Sutter Instrument Co., Novato, CA). The electrode tip resistance was 4–6 MΩ when filled with an intracellular solution containing the following (in mM): 117 K-gluconate, 13.0 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.07 CaCl2, 0.1 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 2 Na2-ATP, and 0.4 Na2-GTP with PH adjusted to 7.3 with KOH and osmolarity 290–295 mOsm. Biocytin (0.5%) was added to this intracellular solution to allow morphological reconstruction of the recorded neurons.

Whole-cell recordings were obtained from the superficial layers of the SC. For V1 injection experiments in C57BL/6J mice, SC cells within the corticotectal termination zones were targeted for recording. For V1 injection experiments in GAD67-GFP mice, GFP-positive or GFP-negative cells within the corticotectal termination zones were targeted for recording. Video images of the patched cell locations, and the presence or absence of GFP within patched cells, were recorded using the CCD camera.

Recordings were obtained with an AxoClamp 2B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) and a Digidata 1440A was used to acquire electrophysiological signals. The stimulation trigger was controlled by Clampex 10.3 software (Molecular Devices). The signals were sampled at 20 kHz and data were analyzed offline by pClamp 10.0 (Molecular Devices). Series resistance was compensated by a bridge protocol and only recordings with stable series resistance and overshooting action potentials were included in the analysis. For current clamp recordings, voltage signals were obtained from cells with resting potentials of −50mV to –65mV. For voltage clamp recordings, membrane currents were obtained at −60mV to −65mV. An 8mV Junction potential was added for all voltage recordings.

For photoactivation of corticotectal terminals, light from a blue light emitting diode (Prizmatix UHP 460) or laser (Coherent Cube 449) was reflected into a 60X water immersion objective. This produced a spot of blue light onto the submerged slice with an approximate diameter of 0.3 mm. Pulse duration and frequency were under computer control. For repetitive stimulation, pulse duration was either 1 or 10 ms. Synaptic responses were recorded using light intensities of 5–60 mW/mm2, and light pulse frequencies of 1Hz, 2Hz, 5Hz, 10Hz and 20Hz.

Morphological analysis of cells filled during physiological recording

Following recording, slices were placed in a fixative solution of 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M phosphate buffer pH 7.4 (PB) for at least 24 hours. The sections were then rinsed in PB and incubated overnight in a 1:1000 dilution of streptavidin-conjugated to Alexafluor-633 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in PB containing 1% Triton X-100. The following day the slices were washed in PB, pre-incubated in 10% normal goat serum (NGS) in PB and then incubated overnight in a 1:500 dilution (0.5 μg/ml) of a rabbit anti-DSred antibody in PB with 1% NGS (Clontech Laboratories, Inc. Mountainview, CA, catalogue #632496, RRID:AB_10015246, created with immunogen DsRed Express, a variant of Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. All DSred antibody binding was confined to cells and terminals that contained TdTomato, as determined by their fluorescence under green epifluorescent illumination; no staining was detected in sections that did not contain TdTomato). The following day the sections were rinsed in PB, and incubated for 1 hour in a 1:100 dilution of a goat-anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to Alexafluor-546 (Invitrogen). The sections were then rinsed in PB and mounted on slides to be imaged with a confocal microscope (Olympus FV1200BX61). For presentation of cell types in relation to surrounding corticotectal terminals, confocal images were imported into Adobe Photoshop software (San Jose, CA) and any extracellular biocytin labeling was removed. The “cleaned” cells were then merged with the unaltered images of the surrounding corticotectal terminals. Finally, Adobe Photoshop software was used to adjust the brightness and contrast of each color channel. Confocal images of labeled cells were categorized based on the following criteria: location of soma, orientation and spread of dendritic fields (as described in Gale and Murphy, 2014), or the presence or absence of GFP in the soma.

Histology for tissue used for anatomical analyses

For animals that were not used for physiological experiments, 1–2 weeks following injection of tracers and/or viruses, mice were deeply anesthetized with Avertin (0.5mg/gm) and transcardially perfused with a fixative solution of 4% paraformaldehyde, or 2% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde in PB. In each case, the brain was removed from the skull and 70 μm thick coronal sections were cut using a vibratome (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). Sections that contained fluorescent labels were mounted on slides and imaged using a confocal microscope (Olympus FV1200BX61), or additionally stained using antibodies as described below.

Selected sections that contained GFP were incubated overnight in a 1:1000 dilution (0.1 μg/ml) of a rabbit anti-GFP antibody in PB with 1% NGS (Millipore, Billerica, MA, catalogue #AB3080, RRID:AB_91337, created with highly purified native GFP from Aequorea victoria as an immunogen. All GFP antibody binding was confined to cells and terminals that contained GFP, as determined by their fluorescence under blue epifluorescent illumination; no staining was detected in sections that did not contain GFP). Sections incubated in the GFP antibody, or sections that contained BDA were incubated in a 1:100 dilution of a biotinylated goat-anti-rabbit antibody (1 hour), followed by avidin and biotinylated horseradish peroxidase (ABC solution, Vector Laboratories, 1 hour) and reacted with nickel-enhanced diaminobenzidine (DAB). The sections were then mounted on slides and imaged using transmitted light, or processed for electron microscopy as described below.

Electron microscopy

Sections that contained terminals labeled by the anterograde transport of BDA, or cells and terminals labeled with the GFP antibody, were postfixed in 2% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in an ethyl alcohol series, and flat embedded in Durcupan resin between two sheets of Aclar plastic (Ladd Research, Williston, VT). Durcupan– embedded sections were first examined with a light microscope to select areas for electron microscopic analysis. Selected areas were mounted on blocks, ultrathin sections (70–80 nm, silver-gray interference color) were cut using a diamond knife, and sections were collected on Formvar-coated nickel slot grids. Selected sections were stained for the presence of gamma amino butyric acid (GABA). A postembedding immunocytochemical protocol described previously (Chomsung et al., 2008, 2010; Day-Brown et al., 2010) was employed. Briefly, we used a 0.25 μg/ml concentration of a rabbit polyclonal antibody against GABA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, catalogue #A2052, RRID:AB_477652, immunogen was GABA conjugated to bovine serum albumin using glutaraldehyde; the GABA antibody shows positive binding with GABA and GABA-keyhole limpet hemocyanin, but not bovine serum albumin (BSA), in dot blot assays (manufacturer’s product information). In mouse tissue, the GABA antibody stains most neurons in the thalamic reticular nucleus and a subset of neurons in the dorsal thalamus and cortex. This labeling pattern is consistent with other GABAergic markers used in a variety of species (Houser et al., 1980; Fitzpatrick et al., 1984; Montero and Singer, 1984; Montero and Zempel, 1985). The GABA antibody was tagged with a goat-anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to 15-nm gold particles (BBI Solutions USA, Madison, WI). The sections were air dried and stained with a 10% solution of uranyl acetate in methanol for 30 minutes before examination with an electron microscope.

Ultrastructural analysis

For analysis of GABA content, ultrathin sections from GAD67-GFP mice were examined using an electron microscope. The gold particle density overlying GFP-labeled profiles was compared to the gold particle density overlying retinotectal terminals (identified by their ultrastructural characteristics) to determine the gold particle density required to identify GABAergic profiles. For analysis of corticotectal synapses, all labeled BDA-terminals involved in a synapse were imaged. The pre- and postsynaptic profiles were characterized on the basis of size (measured using Image J, RRID: nif-000–30467, or Maxim DL © 5 software), the presence or absence of synaptic vesicles, and overlying gold particle density. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons post-test were used for statistical analyses of ultrastructural data. For presentation of ultrastructural features, electron microscopic images were imported into Adobe Photoshop software (San Jose, CA), and the brightness and contrast were adjusted.

Results

Distribution and ultrastructure of V1 corticotectal terminals

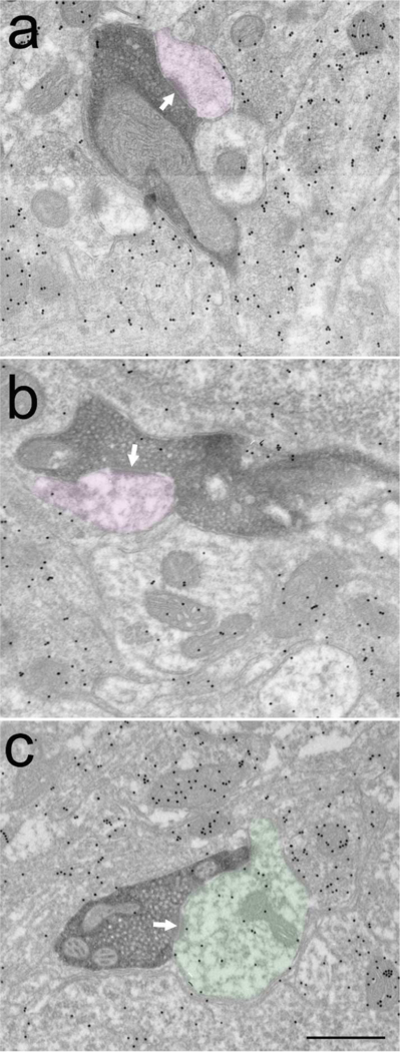

Iontophoretic injections of BDA or AAV in mouse V1 labeled terminals that were distributed in restricted regions of the superficial layers of the SC (as previously described, Wang and Burkhalter, 2013). Corticotectal terminals originating from V1 were distributed in a topographic manner, and restricted to the SGS and SO (Figure 1A,B). Using electron microscopy, tissue containing BDA-labeled terminals was examined and images were collected of all terminals involved in synapses (case 1, n = 101; case 2, n = 113; total n = 214). BDA-labeled corticotectal terminals (Figure 2A-C) were observed to be small profiles (0.38 ± 0.21 μm2; Figure 3C) that contained densely packed round vesicles. Corticotectal terminals primarily contacted (arrows, Figure 2A-C) small caliber (0.31 ± 0.21 μm2; Figure 3C) dendrites with thick postsynaptic densities.

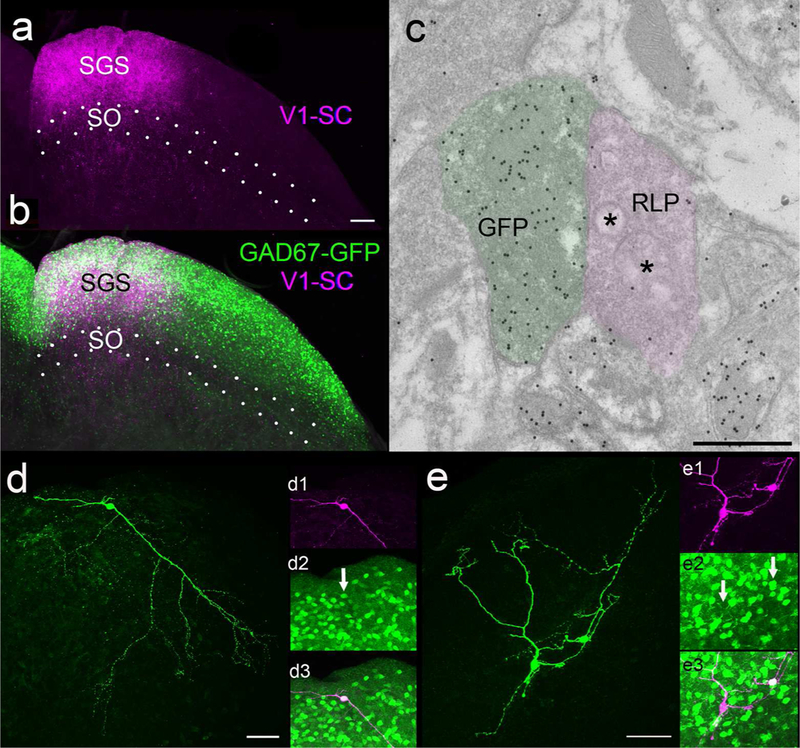

Figure 1:

A) Virus injections in V1 labeled terminals in the stratum griseum superficiale (SGS, A, purple) which overlapped the distribution of cells that contain green fluorescent protein (GFP, B, green) in the GAD67-GFP mouse line. C) Electron microscopic examination of SGS tissue from GAD67-GFP mice stained with a GABA antibody tagged with gold particles revealed a high density of gold particles overlying GFP-labeled profiles (green overlay) and a low density overlying large profiles with round vesicles and pale mitochondria (RLP profiles, purple overlay). D) Example of a biocytin-filled GFP+ neuron (green). D1) The neuron illustrated in D pseudocolored purple. D2) GFP label in the biocytin-filled cell (arrow). D3) Biocytin and GFP are contained in the same cell (white). E) Examples of a biocytin-filled GFP+ and GFP- neurons (green). E1) The neurons illustrated in E pseudocolored purple. E2) GFP label in the upper, but not the lower biocytin-filled cell (arrows). E3) Biocytin and GFP are contained in the upper (white) but not the lower cell (purple). Scale in A = 100 μm and applies to B, Scale in C = 600 nm, Scale in D = 50 μm and applies to D1-D3. Scale in E = 50 μm and applies to E1-E3.

Figure 2:

Corticotectal terminals labeled with diaminobenzidine (dark reaction product) primarily contact (white arrows) non-GABAergic dendrites (purple overlay, A,B). A small percentage of corticotectal terminals contact GABAergic dendrites (C, green overlay). Scale bar = 0.5 μm and applies to all panels.

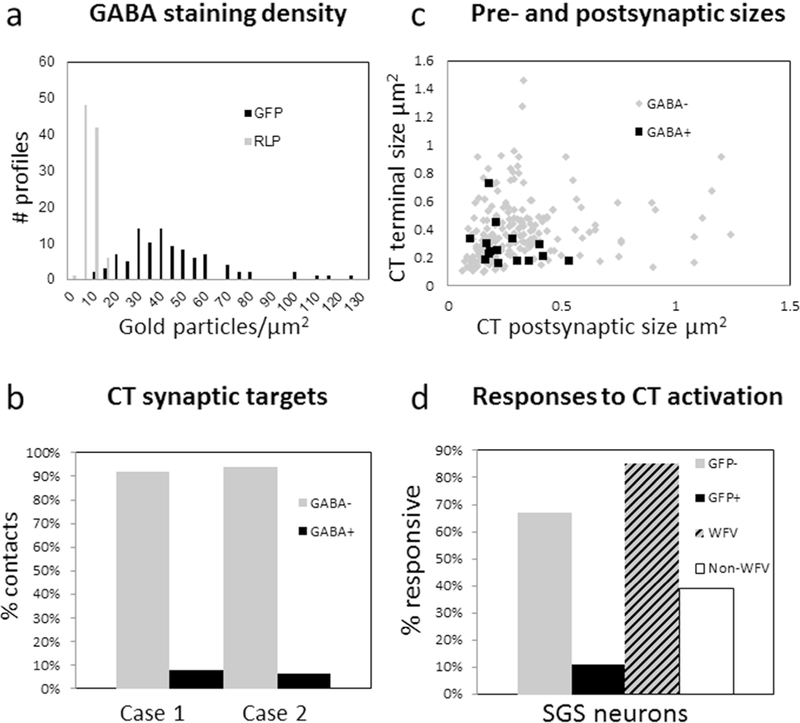

Figure 3:

A) In tissue from GAD67-GFP mice stained with a GABA antibody tagged with gold particles, the gold particle density overlying GFP-labeled profiles (black bars) is greater than the gold particle overlying RLP profiles (gray bars). B) Percentage of corticotectal terminals (CT) found to contact GABAergic (GABA+, black bars) and nonGABAergic (GABA-, gray bars) dendrites (case 1, n = 101, case 2 n = 113). C) Corticotectal terminals were found to be relatively small profiles (0.38 ± 0.21 μm2) that contacted small dendritic profiles (0.31 ± 0.21 μm2). Contacts on nonGABergic dendrites are indicated with gray dots and contacts on GABAergic dendrites are indicated by black squares. The sizes of GABAergic and nonGABAergic postsynaptic dendrites were not found to be statistically different (Mann Whitney, p = 0.6139). D) In slices from GAD67 mice, the majority of cells that did not contain GFP (GFP-, 67%) responded to photoactivation of corticotectal terminals. In contrast, only 11% of cells that contained GFP in GAD67-GFP mice responded to photoactivation of corticotectal terminals. In slices from C57BL/6J mice, the majority of WFV cells (85%) recorded in C57/BLK6 mice responded to photoactivation of corticotectal terminals. In contrast, 39% of the remaining cells (non-WFV) responded to photoactivation of corticotectal terminals.

Tissue containing BDA-labeled terminals was also stained with an antibody against gamma amino butyric acid (GABA) that was tagged to gold particles. The staining density required to identify GABAergic profiles was standardized in tissue from the GAD67-GFP line (Figure 1C); the gold particle density overlying GFP-labeled profiles (n = 98; average of 41.93 ± 22.18 gold particles/μm2) was compared to the gold particle density overlying surrounding glutamatergic retinotectal terminals (n = 97; average 5.11 ± 2.8 gold particles/μm2; identified by their unique “pale” mitochondria with widened cristae; RLP profiles, Boka et al., 2006; Figure 1C, 3A). This analysis revealed that GABAergic profiles could be identified by a density of > 20 gold particles/μm2 (this density was greater than the maximum density overlying retinotectal terminals, and the gold particle density overlying 95% of GFP-labeled profiles was greater than this value). Using this criterion, corticotectal terminals were found to primarily contact nonGABAergic dendrites (case 1: 92%, case 2: 94%; Figure 2A,B) and few GABAergic dendrites (case 1: 8%, case 2: 6%; Figure 2C, 3B).

Optogenetic activation of V1 corticotectal terminals

To activate corticotectal terminals, viral vector injections were placed in V1 of C57BL/6J mice or GAD67-GFP mice to induce the expression of TdTomato and ChIEF in V1 cells and their axon projections (Figure 1A,B). In coronal slices of the SC, whole cell recordings were obtained from neurons in the regions innervated by V1 (n = 122; 85 in slices from 28 successfully injected C57BL/6J mice and 37 in slices from 5 successfully injected GAD67-GFP mice). Pulses of blue light (1 or 10 ms in duration) through the microscope objective were used to activate the light-sensitive channels expressed by the corticotectal terminals. This induced EPSPs with short (2.5 ± 1.2 ms), fixed latencies in 43% of the recorded neurons (53 of 122).

Corticotectal responses in GAD67-GFP mice

To determine whether activation of V1 corticotectal terminals can elicit responses in GABAergic interneurons of the SGS, we carried out a limited number of experiments using GAD67-GFP mice (Figure 1B, D, E), which express GFP in GABAergic interneurons of the SC (Whyland et al., 2017), and targeted our recordings to GFP+ (n = 28) or GFP- (n= 9) cells. In these experiments, 67% of the GFP- cells, but only 11% of the GFP+ cells, responded to photoactivation of V1 corticotectal terminals (Figure 3D). Importantly, responsive GFP- cells and unresponsive GFP+ cells were recorded side by side in the same slices (Figure 1E).

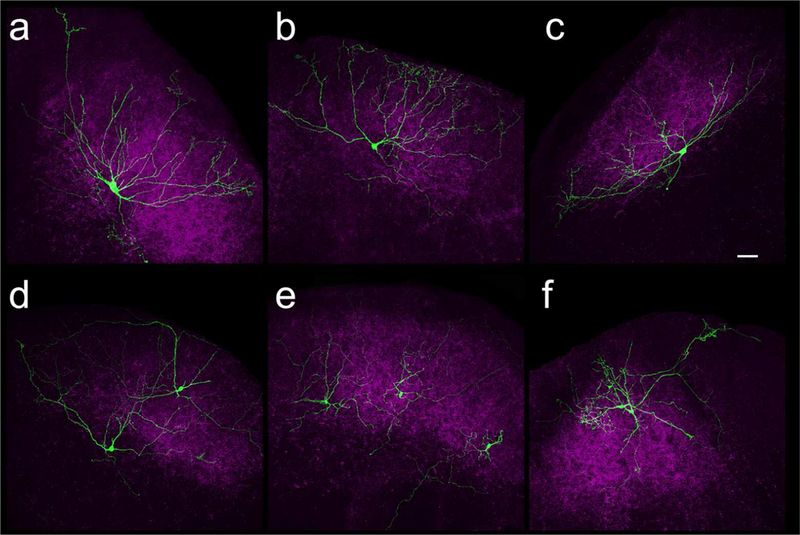

Identification of WFV and non-WFV cells

Pipettes included biocytin so that the morphology of recorded cells and their location relative to TdTomato-labeled corticotectal terminals could be established after recording (of 122 recorded cells, 79 were recovered, and the labeling of 59 of these cells was sufficiently complete to categorize their morphology). We used the following criteria to identify WFV cells: 1) somata located in the lower SGS or upper SO (150–400 um from the surface of the SC), 2) ≥ 3 primary dendrites that radiated from the soma toward the surface of the SC, 3) dendritic field width of ≥ 250 μm and height of at least 50% of the distance from the soma to the SC surface and 4) an angular distance between the most medial and most lateral dendrites of ≥ 100o and ≤ 175o (n = 13; Figure 4A-C). All other biocytin-filled cells were categorized as non-WFV (Figure 4D-F).

Figure 4:

Confocal images of WFV cells (A-C, green) and non-WFV cells (D-F, green). Corticotectal terminals labeled by virus injections in V1 are shown in purple. Scale = 50 μm and applies to all panels.

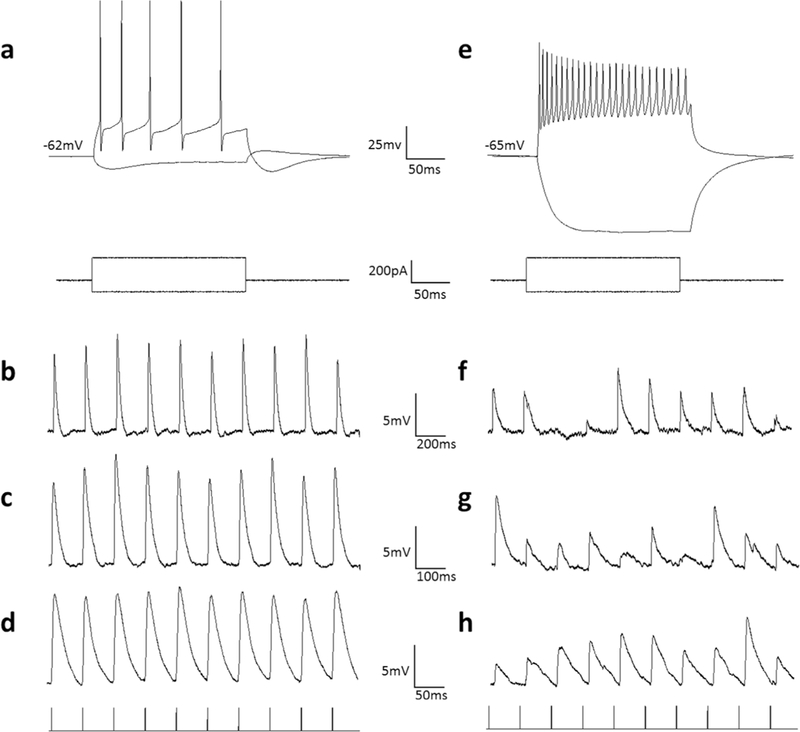

As previously reported (Endo et al., 2008; Gale and Murphy, 2016), the morphologically-identified WFV cells exhibited relatively depolarized membrane potentials (−55 ± 6.8 mV), low membrane resistances (145 ± 75 MΩ), and a strong depolarizing sag in response to hyperpolarizing current injection (> 8 mV depolarization in response to - 50 nA current injection; example illustrated in Figure 5A). In contrast, most non-WFV cells displayed much higher membrane resistances (521 ± 326 MΩ), and resting membrane voltages (−65 ± 7.1 mV; non-WFV example illustrated in Figure 5E).

Figure 5:

WFV and non-WFV cell membrane properties and responses to photoactivation (60 mW/mm2) of corticotectal terminals. A) Voltage responses of a WFV cell to injection of depolarizing and hyperpolarizing current steps. WFV cells display a low membrane resistance and a depolarizing sag in response to hyperpolarizing current steps. B-C) Excitatory postsynaptic potentials evoked in the WFV of panel A in response to 5Hz (B), 10Hz (C) and 20Hz (D) photoactivation of surrounding corticotectal terminals. WFV cell corticotectal response amplitudes remained stable at all frequencies. E) Voltage responses of a non-WFV cell to injection of depolarizing and hyperpolarizing current steps. F-G) Excitatory postsynaptic potentials evoked in the non-WFV of panel E in response to 5Hz (F), 10Hz (G) and 20Hz (H) photoactivation of surrounding corticotectal terminals. Non-WFV cell corticotectal response amplitudes varied widely; increasing photoactivation frequency did not induce consistent facilitation or depression of responses.

Corticotectal responses in WFV and non-WFV cells

The majority of recordings were carried out in C57BL/6J mice in which neurons were randomly targeted for recording, within zones of TdTomato/ChIEF-expressing corticotectal terminals. In these experiments, 52% of the recorded neurons (44/85) responded to photactivation of V1 corticotectal terminals. Of 13 identified WFV cells, 11 (85%) were found to be responsive to photoactivation of corticotectal terminals (Figure 3D, WFV). The response rate of the remaining cells was considerably lower (33/85 or 39%, Figure 3D, non-WFV), but the membrane resistance and resting membrane potential of responsive (543 ± 241 MΩ; −65.8 ± 7.2 mV) and non-responsive cells (508 ± 368 MΩ; −67.9 ± 7.5 mV) were not found to be statistically different (p = 0.625; p = 0.76). It should be noted that this non-WFV cell category could include GABAergic neurons. Therefore our data does not allow us to determine the response rate of nonWFV/non-GABAergic cell types. In addition, only 21 of the 33 responsive non-WFV cells were successfully filled with biocytin and recovered. The morphologies of these cells were quite variable. Therefore, we did not subdivide the responsive non-WFV cells further based on morphological characteristics.

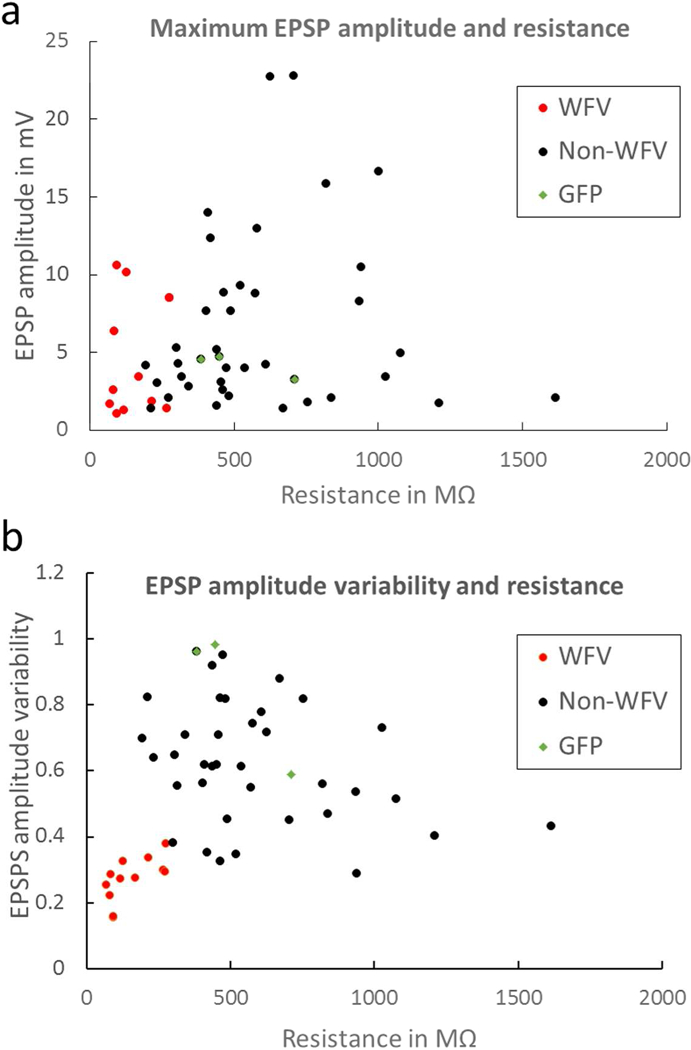

V1 corticotectal terminals were activated with trains of light pulses (1, 2, 5, 10, 20 Hz) to determine whether corticotectal responses exhibit frequency-dependent synaptic depression or facilitation. However, we found that, with the exception of WFV cells (Figure 5B-D), the majority of corticotectal responses were quite variable across trials (Figure 5 F-H) and did not exhibit consistent facilitation or depression of responses. To compare the variability of responses, we calculated the standard deviation of the EPSPs evoked by all frequencies. As illustrated in Figure 6B, the variability of responses was greatest in cells with membrane resistances > 200 MΩ, whereas all WFV cells exhibited stable responses across all frequencies. The maximum EPSP amplitudes recorded in response to photoactivation of V1 terminals are plotted in Figure 6A.

Figure 6:

A) The maximum EPSP amplitudes recorded (in response to a single pulse within a train, data from both C57BL/6J and GAD67-GFP mice) in WFV cells (red dots), non-WFV cells (black dots), and GFP+ cells (green diamonds), plotted as a function of input resistance. B) The variability in EPSP amplitudes (standard deviation, see text for details) plotted as a function of input resistance for WFV cells, non-WFV cells, and GFP+ cells. WFV cell response amplitudes were the least variable.

Discussion

The main findings of this study are that 1) corticotectal terminals rarely contact GABAergic SC interneurons, and 2) although V1 corticotectal terminals contact a variety of cells types in the superficial SC, their influence on WFV cells is the most uniform. Below we discuss features of corticotectal terminals and WFV cells that may account for this finding. In addition, we discuss how V1 corticotectal connections may enhance the behavioral output of the SC.

Ultrastructure of corticotectal terminals and their postsynaptic targets

The ultrastructure of V1 corticotectal terminals and their postsynaptic targets in the mouse are remarkably similar to those of our previous study of V1 corticotectal terminals in the rat (Boka et al., 2006). In both species, corticotectal terminals are restricted to the SGS and SO and are small terminals (mouse 0.38 ± 0.21 μm2; rat 0.44 ± 0.27 μm2) that contain densely packed round vesicles and contact small caliber dendrites (mouse 0.31 ± 0.21 μm2; rat 0.51 ± 0.69 μm2). Finally, in both species, using the same postembedding immunocytochemical techniques to detect GABA, we found that corticotectal terminals primarily contact nonGABAergic dendrites (93% in both species). Given that nearly half of the neurons in the SGS are GABAergic (Whyland et al 2017; Mize, 1988), these results suggest that V1 corticotectal terminals preferentially target nonGABAergic cells in the SGS.

The main caveat of these results is that our GABA staining may not detect all GABAergic profiles, particularly small dendrites that do not accumulate significant levels of GABA. However, the relative sparsity of corticotectal inputs on GABAergic neurons was confirmed by our in vitro recording experiments. We found that only 11% of GFP-labeled neurons in the GAD67-GFP mouse line responded to optogenetic activation of surrounding corticotectal terminals, whereas 67% of GFP-negative cells in the mouse line responded to corticotectal input (in many cases corticotectal responses were recorded in GFP-negative cells that were adjacent to non-responsive GFP-positive cells). In addition, comparison of GABA staining over GFP-labeled profiles and retinotectal terminals in GAD67-GFP demonstrated that our immunocytochemical techniques detected GABA in the vast majority of GFP-labeled profiles. Moreover, dendrites categorized as GABAergic were not larger than those categorized as nonGABAergic. Finally, identical postembedding immunocytochemical techniques detected GABA in 27% of profiles postsynaptic to retinotectal terminals (Boka et al., 2006).

Features of WFV cells

WFV cells are unique in that their widespread dendrites express voltage-dependent Na+ channels which can generate dendritic spikes that propagate toward the soma (Luksch et al., 1998, 2001; Endo et al., 2008; Gale and Murphy, 2016). In addition, the dendrites of WFV cells express the hyperpolarization-activated cation channel 1 (HCN1) which facilitates the initiation and/or propagation of dendritic spikes (Endo et al., 2008). These features ensure that retinal signals are efficiently transferred from the superficial dendritic tips in the upper SGS to the soma, located in the lower SGS/SO. These features also likely contribute to the stable responses of WFV cells to optogenetic activation of V1 corticotectal terminals.

Two previous mechanisms have been identified that regulate the output of WFV cells. In birds, electron microscopic studies of WFV cells have revealed that their distal dendrites participate in glomerulus-like synaptic arrangements with terminals that originate from the retina and nucleus isthmi (homologue of the parabigeminal nucleus; González-Cabrera et al., 2016). These convergent inputs interact to boost the response of WFV cells to retinal input within restricted regions of the visual field (Marin et al., 2012). In the mouse, WFV cells have been demonstrated to receive convergent input from the retina and GABAergic interneurons (Gale and Murphy, 2016; Zingg et al., 2017). Retinal terminals and GABAergic interneurons also interact in glomerulus-like synaptic arrangements (Boka et al., 2006), which may restrict the responses of WFV cells to stimuli that are both small and moving; when interneuron input to WFV cells is inhibited, they respond to larger, looming visual stimuli (Gale and Murphy, 2016). Our results suggest that V1 corticotectal inputs provide a third mechanism to modulate WFV cell output, potentially increasing the gain of responses to looming visual stimuli (Zhao et al., 2014), via increased excitation of WFV cells that is not offset by increases in GABAergic interneuron inhibition.

Other postsynaptic targets of V1 corticotectal terminals

We found that most nonGABAergic cell types in the superficial SC responded to activation of V1 corticotectal terminals. Likewise, transynaptic viral tracing methods demonstrated that in addition to WFV cells, V1 corticotectal terminals innervate nonGABAergic cells that project to the parabigeminal nucleus (PBG), dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN), and pretectum (PT). Although the superficial SC sends GABAergic projections to the ventral lateral geniculate nucleus (vLGN), PT, PBG and contralateral SC (Gale and Murphy, 2014; Whyland et al., 2017), GABAergic cells transynaptically labeled after V1 viral injections were all found to be intrinsic interneurons (Zingg et al., 2017). Our results further suggest that few GABAergic interneurons are contacted by corticotectal terminals. We found that only 7% of corticotectal terminals contacted GABAergic dendrites, and only 11% of GAD67-GFP positive cells responded to optogenetic activation of corticotectal terminals. However, although we and others have demonstrated that the GAD67-GFP line labels GABAergic interneurons in the SGS (Whyland et al., 2017; Villalobos et al., 2018), it is possible GFP-labeled neurons in this line constitute only a subset of interneurons.

In contrast to the responses of WFV cells, the EPSP amplitudes recorded in the majority of non-WFV cells in response to photostimulation of corticotectal axons were quite variable during the course of stimulus trains. It is unlikely that this variability is an artifact of our optogenetic activation methods because we have used identical techniques to study corticogeniculate and tectogeniculate pathways and have found that these pathways exhibit frequency-dependent facilitation and depression, respectively (Jurgens et al., 2012; Bickford et al., 2015). It is possible that the non-WFV cells which exhibit variable response amplitudes receive sparse corticotectal input that is offset by their high input resistance to result in robust postsynaptic responses. In vivo spike triggered averaging/current source density analysis indicates that, as a population, corticotectal inputs exhibit frequency-dependent depression (Bereshpolova et al., 2006). Thus, sparse inputs could potentially result in greater fluctuation in EPSP amplitudes during stimulus trains.

Corticotectal enhancement of behavioral responses

Detection of rapidly approaching or looming objects is critical to survival; these stimuli must trigger quick responses to avoid collision. Looming visual stimuli have been shown to preferentially activate the human SC and pulvinar (Billington et al., 2011) or homologous structures across species (Sun and Frost, 1998; Wu et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2014). When mice are presented with overhead visual stimuli, they respond with escape or freezing behavior, dependent on the stimulus, the presence of a shelter during testing, as well as previous colony housing conditions (Yilmaz and Meister, 2013; De Franceschi et al., 2016; Vale et al., 2017). Our results suggest that V1 corticotectal projections may enhance these behavioral responses via a combination of a relatively weak influence on GABAergic interneurons, and sustained excitation of WFV cells. The subsequent convergence of inputs from multiple WFV cells onto individual pulvinar neurons (Chomsung et al., 2008; Masterson et al., 2010; Wei et al., 2011) may further boost the influence of V1 on SC-mediated behavior.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Arkadiusz Slusarczyk for his excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by the National Eye Institute (R01EY024173), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R21NS104807), and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P20GM1034236).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References cited:

- Basso MA, May PJ. 2017. Circuits for Action and Cognition: A View from the Superior Colliculus. Annu Rev Vis Sci [Internet] 3:annurev-vision-102016–061234. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28617660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bereshpolova Y, Stoelzel CR, Gusev AG, Bezdudnaya T, Swadlow HA. 2006. The Impact of a Corticotectal Impulse on the Awake Superior Colliculus. J Neurosci [Internet] 26:2250–2259. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16495452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickford ME, Zhou N, Krahe TE, Govindaiah G, Guido W. 2015. Retinal and Tectal “Driver-Like” Inputs Converge in the Shell of the Mouse Dorsal Lateral Geniculate Nucleus. J Neurosci [Internet] 35:10523–34. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26203147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billington J, Wilkie RM, Field DT, Wann JP. 2011. Neural processing of imminent collision in humans. Proc Biol Sci [Internet] 278:1476–81. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3081747&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boka K, Chomsung R, Li J, Bickford ME. 2006. Comparison of the ultrastructure of cortical and retinal terminals in the rat superior colliculus. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol [Internet] 288:850–8. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2561302&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomsung RD, Petry HM, Bickford ME. 2008. Ultrastructural examination of diffuse and specific tectopulvinar projections in the tree shrew. J Comp Neurol [Internet] 510:24–46. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18615501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomsung RD, Wei H, Day-Brown JD, Petry HM, Bickford ME. 2010. Synaptic organization of connections between the temporal cortex and pulvinar nucleus of the tree shrew. Cereb Cortex [Internet] 20:997–1011. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19684245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day-Brown JD, Wei H, Chomsung RD, Petry HM, Bickford ME. 2010. Pulvinar projections to the striatum and amygdala in the tree shrew. Front Neuroanat [Internet] 4:143 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21120139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Franceschi G, Vivattanasarn T, Saleem AB, Solomon SG. 2016. Vision Guides Selection of Freeze or Flight Defense Strategies in Mice. Curr Biol [Internet] 26:2150–2154. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27498569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo T,Tarusawa E, Notomi T, Kaneda K, Hirabayashi M, Shigemoto R, Isa T. 2008. Dendritic Ih ensures high-fidelity dendritic spike responses of motion-sensitive neurons in rat superior colliculus. J Neurophysiol [Internet] 99:2066–76. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18216232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick D, Penny GR, Schmechel DE. 1984. Glutamic acid decarboxylaseimmunoreactive neurons and terminals in the lateral geniculate nucleus of the cat. J Neurosci [Internet] 4:1809–29. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6376726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale SD, Murphy GJ. 2014. Distinct representation and distribution of visual information by specific cell types in mouse superficial superior colliculus. J Neurosci [Internet] 34:13458–71. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25274823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale SD, Murphy GJ. 2016. Active Dendritic Properties and Local Inhibitory Input Enable Selectivity for Object Motion in Mouse Superior Colliculus Neurons. J Neurosci [Internet] 36:9111–23. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27581453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Cabrera C, Garrido-Charad F, Mpodozis J, Bolam JP, Marín GJ. 2016. Axon terminals from the nucleus isthmi pars parvocellularis control the ascending retinotectofugal output through direct synaptic contact with tectal ganglion cell dendrites. J Comp Neurol [Internet] 524:362–379. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26224333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houser CR, Vaughn JE, Barber RP, Roberts E. 1980. GABA neurons are the major cell type of the nucleus reticularis thalami. Brain Res [Internet] 200:341–54. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7417821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurgens CWD, Bell KA, McQuiston AR, Guido W. 2012. Optogenetic stimulation of the corticothalamic pathway affects relay cells and GABAergic neurons differently in the mouse visual thalamus. PLoS One [Internet] 7:e45717 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23029198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang F, Xiong XR, Zingg B, Ji X-Y, Zhang LI, Tao HW. 2015. Sensory Cortical Control of a Visually Induced Arrest Behavior via Corticotectal Projections. Neuron [Internet] 86:755–67. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25913860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R-F, Niu Y-Q, Wang S- R. 2008. Thalamic neurons in the pigeon compute distanceto-collision of an approaching surface. Brain Behav Evol [Internet] 72:37–47. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18635928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luksch H, Cox K, Karten HJ. 1998. Bottlebrush dendritic endings and large dendritic fields: motion-detecting neurons in the tectofugal pathway. J Comp Neurol [Internet] 396:399–414. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9624592 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luksch H, Karten HJ, Kleinfeld D, Wessel R. 2001. Chattering and differential signal processing in identified motion-sensitive neurons of parallel visual pathways in the chick tectum. J Neurosci [Internet] 21:6440–6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11487668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin GJ, Duran E, Morales C, Gonzalez-Cabrera C, Sentis E, Mpodozis J, Letelier JC. 2012. Attentional Capture? Synchronized Feedback Signals from the Isthmi Boost Retinal Signals to Higher Visual Areas. J Neurosci [Internet] 32:1110–1122. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22262908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masterson SP, Li J, Bickford ME. 2010. Frequency-dependent release of substance P mediates heterosynaptic potentiation of glutamatergic synaptic responses in the rat visual thalamus. J Neurophysiol [Internet] 104:1758–67. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2944677&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero VM, Singer W. 1984. Ultrastructure and synaptic relations of neural elements containing glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) in the perigeniculate nucleus of the cat. A light and electron microscopic immunocytochemical study. Exp brain Res [Internet] 56:115–25. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6381084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero VM, Zempel J. 1985. Evidence for two types of GABA-containing interneurons in the A-laminae of the cat lateral geniculate nucleus: a double-label HRP and GABA-immunocytochemical study. Exp brain Res [Internet] 60:603–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2416585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranney Mize R 1988. Immunocytochemical localization of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the cat superior colliculus. J Comp Neurol [Internet] 276:169–187. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3220979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X, Barchini J, Ledesma HA, Koren D, Jin Y, Liu X, Wei W, Cang J. 2017. Retinal origin of direction selectivity in the superior colliculus. Nat Neurosci [Internet] 20:550–558. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28192394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Frost BJ. 1998. Computation of different optical variables of looming objects in pigeon nucleus rotundus neurons. Nat Neurosci [Internet] 1:296–303. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10195163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale R, Evans DA, Branco T. 2017. Rapid Spatial Learning Controls Instinctive Defensive Behavior in Mice. Curr Biol [Internet] 27:1342–1349. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28416117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villalobos CA, Wu Q, Lee PH, May PJ, Basso MA. 2018. Parvalbumin and GABA Microcircuits in the Mouse Superior Colliculus. Front Neural Circuits [Internet] 12:35 Available from: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fncir.2018.00035/full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Burkhalter A. 2013. Stream-Related Preferences of Inputs to the Superior Colliculus from Areas of Dorsal and Ventral Streams of Mouse Visual Cortex. J Neurosci [Internet] 33:1696–1705. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23345242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H, Masterson SP, Petry HM, Bickford ME. 2011. Diffuse and specific tectopulvinar terminals in the tree shrew: synapses, synapsins, and synaptic potentials. PLoS One [Internet] 6:e23781 Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3156242&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei P, Liu N, Zhang Z, Liu X, Tang Y, He X, Wu B, Zhou Z, Liu Y, Li J, Zhang Y, Zhou X, Xu L, Chen L, Bi G, Hu X, Xu F, Wang L. 2015. Processing of visually evoked innate fear by a non-canonical thalamic pathway. Nat Commun [Internet] 6:6756 Available from: http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/ncomms7756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyland KL, Whyland KL, Masterson SP, Slusarczyk AS, Govindaiah G, Guido W, Bickford ME (2017) Feedforward inhibitory circuits within the mouse superior colliculus. Society for Neuroscience abstract [Google Scholar]

- Wu L-Q, Niu Y-Q, Yang J, Wang S- R. 2005. Tectal neurons signal impending collision of looming objects in the pigeon. Eur J Neurosci [Internet] 22:2325–31. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16262670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz M, Meister M. 2013. Rapid innate defensive responses of mice to looming visual stimuli. Curr Biol [Internet] 23:2011–5. Available from:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24120636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Liu M, Cang J. 2014. Visual Cortex Modulates the Magnitude but Not the Selectivity of Looming-Evoked Responses in the Superior Colliculus of Awake Mice. Neuron [Internet] 84:202–213. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25220812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou NA, Maire PS, Masterson SP, Bickford ME. 2017. The mouse pulvinar nucleus: Organization of the tectorecipient zones. Vis Neurosci 34 E011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou N, Masterson SP, Damron JK, Guido W, Bickford ME. 2018. The Mouse Pulvinar Nucleus Links the Lateral Extrastriate Cortex, Striatum, and Amygdala. J Neurosci [Internet] 38:347–362. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29175956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zingg B, Chou X, Zhang Z, Mesik L, Liang F, Tao HW, Zhang LI. 2017. AAV-Mediated Anterograde Transsynaptic Tagging: Mapping Corticocollicular Input-Defined Neural Pathways for Defense Behaviors. Neuron [Internet] 93:33–47. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27989459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]