Abstract

Neurocysticercosis (NCC) is an important neurological disease in countries with high prevalence of Taenia solium infection and is emerging as a serious public health and economic problem. The aim of this study was to estimate the prevalence of NCC in Angónia district, Tete province, Mozambique based on: prevalence of human T. solium cysticercosis assessed by antigen Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (Ag-ELISA) seropositivity, history of epilepsy, and brain computed tomography (CT) scan results. A cross sectional study was conducted between September and November 2007 in Angónia district. Questionnaires and blood samples were collected from 1,723 study subjects. Brain CT-scans were carried out on 151 study subjects with confirmed history of epilepsy. A total of 77 (51.0% (95% CI, 42.7–59.2)) and 38 (25.2% (95% CI, 18.5–32.9)) subjects met the criteria for definitive and probable diagnosis of NCC, respectively. T. solium Ag-ELISA seropositivity was found in 15.5% (95% CI, 12.8–16.2) of the study subjects. The estimated life time prevalence of epilepsy was 8.8% (95% CI, 7.5–10.2). Highly suggestive lesions of NCC were found on CT-scanning in 77 (71.9%, (95% CI, 62.4–80.2)) of the seropositive and 8 (18.1%, (95% CI, 8.2–32.7)) of the seronegative study subjects, respectively. The present findings revealed a high prevalence of NCC among people with epilepsy in Angónia district. Determination of effective strategies for prevention and control of T. solium cysticercosis are necessary to reduce the burden of NCC among the affected populations.

Keywords: Taenia solium cysticercosis, Neurocysticercosis, Epilepsy, Computed tomography scan, Antigen Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent, Assay, Mozambique

1. Introduction

Neurocysticercosis (NCC) is an important neurological disease in countries with high prevalence of Taenia solium infection and is reported to be a re-emerging problem in high income countries (Fabiani and Bruschi, 2013; Serpa and White, 2012). The condition develops when a person ingests parasite eggs present in stool of patients with taeniosis (Roman et al., 2000). Taeniosis is acquired by eating raw or undercooked infected pork. While patients with taeniosis generally exhibit little or no clinical signs and symptoms, a different scenario is observed in patients with NCC. Epilepsy is a common clinical presentation (Carabin et al., 2011; Del Brutto and Del Brutto, 2012; Del Brutto and Garcia, 2013; Winkler et al., 2009b) and leading cause of morbidity in patients with NCC (Dewhurst et al., 2013; Tegueu et al., 2013). Epilepsy is considered a major health problem in low and middle income countries, where the prevalence has shown to be much higher than in high income countries (Ngugi et al., 2010). Two systematic reviews have recently provided an updated estimate for the overall prevalence of epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa but did not include data from Mozambique (Ngugi et al., 2010; Paul et al., 2012). Ndimubanzi et al. (2010) estimated in a systematic review that NCC occurred in 29% of people with epilepsy, while Quet et al. (2010) revealed a significant association between cysticercosis and epilepsy in a meta-analysis including only African studies (Ndimubanzi et al., 2010; Quet et al., 2010). Several studies on porcine cysticercosis have been carried out in Tete province, Mozambique and have provided an indication that the zoonotic parasite is wide spread in the area (Pondja et al., 2010; Pondja et al., 2015). The burden it poses on the human population has not been assessed so far. The aim of this study was to estimate the prevalence of NCC in Angónia district, a rural area of Mozambique based on: prevalence of human T. solium cysticercosis assessed by antigen Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) seropositivity, history of epilepsy, and brain computed tomography (CT) scan results.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethical statement

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee of the Medical Faculty of Eduardo Mondlane University, the National Bioethics Committee of Mozambique, the Danish National Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics, Denmark and the Faculty of Health Sciences Ethics Committee at the University of Pretoria, South Africa.

Written informed consent was obtained from all study subjects before interview and sample collection. Study subjects who could not sign their name used fingerprint. Participation was voluntary and study subjects were free to withdraw from the study at any time. All patients’ data from the study were anonymized. Treatment was offered free of charge according to national treatment guidelines. If at any time the study subject developed any clinical complication or side effect, the study subject, parent or guardian was instructed to report immediately to the local health care center.

2.2. Study area and population

The study was conducted in Angónia district, Tete province, Mozambique. The district has two administrative posts – Ulongue and Domue – and sixteen towns which are subdivided into 307 villages and communities. In 2005 the total population of the district was 330,378 people. The main economic activity of the district was mixed farming, including pig rearing. Health care access was limited to one rural hospital, four health centres and three health points. Inhabitants of the area also consult traditional healers (Direcção Distrital de Agricultura de Angónia, 2005).

2.3. Study design and sampling

A community-based cross sectional study was conducted between September and November 2007. Sample size estimation was calculated based on an expected prevalence of human cysticercosis of 20% in the study area (Vilhena and Bouza, 1994). Using single proportion calculation and the following formula n = Z2p(1-p)/d2, the sample size was estimated to be 1600 in the district (p = 0.2, SE = 0.0196) (Wayne, 1999). Sampling with probability proportional to size was used to select the villages. Systematic random sampling was used to select the households to be included. At each household a list of all members was obtained from which one of the available participants was then randomly selected (Chromy, 2008). Criteria of eligibility were: living in the household. Prior to the start of the survey, an initial field visit was made in order to explain the purpose of the study to the local authorities and villagers. In total 1,723 study subjects originating from 18 villages and towns of Angónia district were included.

2.4. Questionnaire

A field tested questionnaire, based on the one developed by the Cysticercosis Working Group of Eastern and Southern Africa, was administered to the study subjects to record data on risk factors for T. solium cysticercosis and other related information, such as pig ownership, pork consumption and history of epileptic seizures (Mwanjali et al., 2013). All questionnaires were translated from English to the local language Chichewa, and back translated to English. Interviews were conducted by paramedical staff that spoke the local language and who had received training during the preparation phase of the study. Study subjects, who during the questionnaire reported having had epileptic seizures in the past, were further interviewed by the principal investigator (first author) to confirm a history of epilepsy.

2.5. Definition of epilepsy

Epilepsy was defined, according to the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE), as two or more unprovoked epileptic seizures separated by at least 24 h and unrelated to acute metabolic disorders or to withdrawal of drugs or alcohol (Fisher et al., 2005; ILAE International League Against Epilepsy, 1993). Lifetime prevalence of epilepsy (LPE) was defined as the proportion of patients identified with a history of epilepsy at any time, regardless of treatment or recent seizure activity. Lifetime prevalence of epilepsy included patients with active epilepsy or epilepsy in remission with or without treatment (ILAE International League Against Epilepsy, 1993).

2.6. Blood sampling

A venous blood sample (4.5 ml) was obtained from each study subject. Serum was separated by centrifugation in the field and stored at −20 °C in cryotubes (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) in the blood bank of the Rural Hospital. The samples were transported from Tete to Maputo in dry ice and stored at the division of Parasitology, Medical Faculty, Eduardo Mondlane University, in Mozambique before transport to School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Zambia, in Zambia. Here the serum samples were tested for circulating antigens of the metacestode of T. solium (Ag-ELISA (B185/B60) using the Ag-ELISA assay (Brandt et al., 1992; Dorny et al., 2000; Nguekam et al., 2003). The Ag-ELISA assay has shown to have a sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 98% in detecting current infection with T. solium metacestodes (Praet et al., 2010). Negative reference control sera from local people and one positive control reference serum from a patient with confirmed cysticercosis were included in each ELISA run. The optical density (OD) of each serum sample was compared with the mean of the eight negative reference sera at a probability level of p-value = 0.001 to determine the result using a modified Student’s t-test (Sokal and Rohlf, 1995). The ELISA ratio was calculated by dividing the OD of the sample by the calculated cut-off value of the eight negative controls. An ELISA ratio bigger than one (ratio > 1) was considered positive (Dorny et al., 2004; Somers et al., 2006).

2.7. Brain CT-scan

Study subjects with confirmed history of epilepsy were transported to Beira Central Hospital, in Sofala province to have a CT-scan of the brain to ascertain presence of lesions suggestive of NCC. Brain CT-scan examinations were carried out using a Somatom emotion helicoidal, version A45A (Germany). In case lesions suggestive of NCC were found, the intravascular contrast agent Ultravist-370 was used. Each patient was monitored by a physician before, during and after contrast injection. Brain CT-scans were analysed independently by two neurologists from Beira and Maputo Central Hospital.

Brain lesions were classified as: vesicular, colloidal, nodular-granular and calcified (Escobar and Weidenheim, 2002). Any cystic lesion without scolex was categorized as lesion highly suggestive of NCC (Del Brutto et al., 2001).

2.8. Diagnostic criteria for NCC

Neurocysticercosis was diagnosed according to modified criteria proposed by Del Brutto et al. (2001). A modification of one major diagnostic criteria was made as the positive Enzyme-linked Immunoelectrotransfer Blot (EITB) test was replaced by the serum Ag-ELISA test (Gabriel et al., 2012; Praet et al., 2010). The latter counted together with the presence of highly suggestive lesions of NCC on CT-scan, as two major criteria. Epilepsy was considered a clinical manifestation suggestive of NCC and counted as one minor criteria. Study subjects with two major, one minor and one epidemiological criteria were considered to have a definitive diagnosis of NCC, while study subjects with one major, one minor and one epidemiological criteria were considered to have a probable diagnosis of NCC (Del Brutto, 2012; Del Brutto et al., 2001).

2.9. Data management and analysis

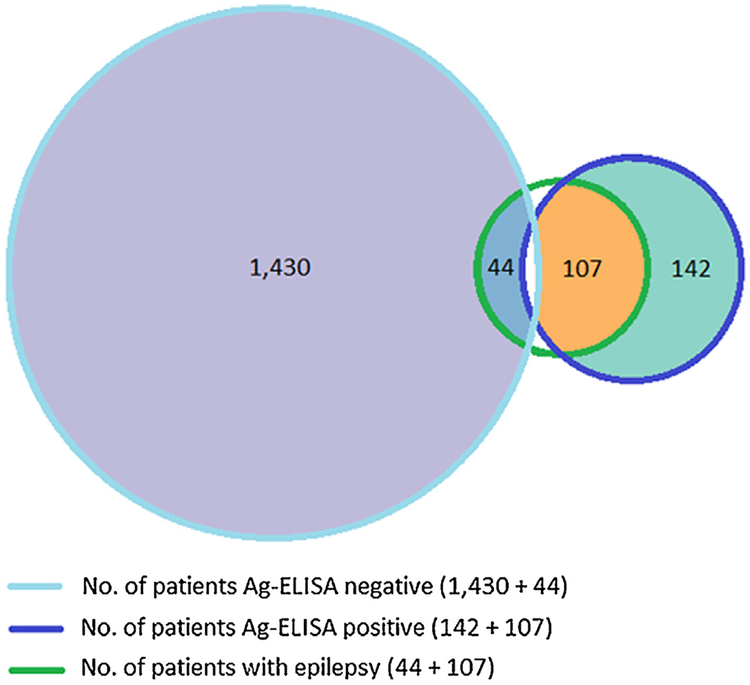

All record forms were checked for consistency using EpiInfo software 2002 (Center for Disease Control, Atlanta, Georgia, USA) and analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Scientist (SPSS) version 20 (SPSS Corp., Chicago, IL). A multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the potential association between T. solium Ag-ELISA seropositivity and factors such as: gender, presence of a latrine at household level, consuming pork, keeping pigs and source of water, however non-significant risk factors were excluded from the model. Crude odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used for the interpretation of the multivariate analysis. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant. Lifetime prevalence of epilepsy was calculated by dividing the total number of study subjects with confirmed history of epilepsy by the total number of interviewed people. Positive predictive values (PPV) for the questionnaire were computed by dividing the number of cases with confirmed history of epilepsy by the number of study subjects who reported having had epileptic seizures in the questionnaire. A Venn diagram was used to allocate subjects according to Ag-ELISA seropositivity with and without a confirmed history of epilepsy.

3. Results

3.1. Serological results

Out of 1,723 interviewed study subjects, 27.5% were males and 72.5% were females. The average age was 30 ± 15.5 years. All 1,723 study subjects provided a blood sample for Ag-ELISA test. The test was positive in 249 (15.5% (95% CI, 12.8–16.2)) study subjects. Multiple logistic regression analysis indicated that males had a higher risk for a positive test in comparison to females (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.6–2.8). Furthermore it was observed that absence of a latrine at household level (OR 0.6, 95% CI, 0.4–0.8) was significantly associated with a positive test. Eating pork, keeping pigs and source of drinking water were not found to be significantly associated with a positive test.

3.2. Lifetime prevalence of epilepsy

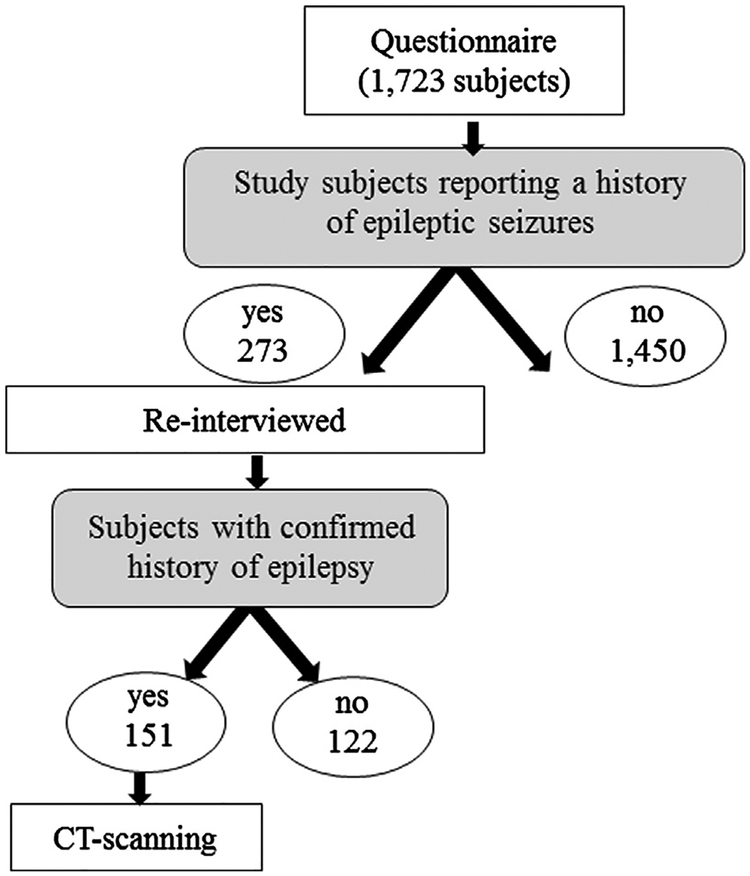

Out of 1,723 interviewed study subjects, 273 reported a history of epileptic seizures (15.8%, (95% CI, 14.2–17.7)). Of those, 151 were confirmed to have a history of epilepsy and underwent brain CT-scanning (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Diagram showing the flow chart from questionnaire to CT-scanning.

Of the people with confirmed history of epilepsy, only 14.6% (95% CI, 9.4–21.2) had previously been treated. The average age at first seizure onset was 18 ± 14.7 years.

Based on the number of study subjects with confirmed history of epilepsy, the estimated LPE was 8.8% (95% CI, 7.5–10.2). The overall PPV of the screening questionnaire for confirmed history of epilepsy was 55.3% (95% CI, 49.2–61.3).

A total of 107 (70.9 % (95% CI, 62.9–78.0)) study subjects with confirmed history of epilepsy were Ag-ELISA positive (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Three-set Venn diagram. Number of study subjects Ag-ELISA positive or negative and number of study subjects Ag-ELISA positive or negative with confirmed history of epilepsy.

3.3. Brain CT-scan results

A total of 151 study subjects with confirmed history of epilepsy underwent a CT-scan of the brain. The average age of the study subjects was 29 ± 7.4 years. Out of 151 study subjects with confirmed history of epilepsy, 107 (70.9%, (95% CI, 62.9–78.0)) were Ag-ELISA positive. Highly suggestive lesions of NCC were found on CT-scans in 77 (71.9%, (95% CI, 62.4–80.2)) of the seropositive and 8 (18.1%, (95% CI, 8.2–32.7)) of the seronegative study subjects, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number and percentage (%) of study subjects Ag-ELISA seropositive and seronegative with a confirmed history of epilepsy and respective brain CT-scan findings.*

| Brain CT-scan findings | Ag-ELISA positive + epilepsy | Ag-ELISA negative + epilepsy | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of study subjects | % | No. of study subjects | % | |

| Vesicular | 19 | 18.8 | 1 | 2.3 |

| Colloidal | 8 | 7.5 | 1 | 2.3 |

| Nodular-granular | 4 | 3.7 | 4 | 9.1 |

| Calcified | 35 | 32.7 | 2 | 4.5 |

| Fibrous arachnoiditis | 1 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Cysticercotic encephalitis | 3 | 2.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Vesicular + calcified | 7 | 6.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Normal CT-scan | 30 | 28.0 | 36 | 81.8 |

| Total | 107 | 100 | 44 | 100 |

CT: computed tomography scan; Ag-ELISA: antigen-Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay.

3.4. Diagnosis and prevalence of NCC

A total of 77 (51.0% (95% CI, 42.7–59.2)) and 38 (25.2% (95% CI, 18.5–32.9)) study subjects with confirmed history of epilepsy that underwent CT-scanning met the criteria for definitive and probable diagnosis of NCC, respectively. Study subjects diagnosed with definitive NCC had highly suggestive NCC lesions and were Ag-ELISA positive. Among study subjects with a probable diagnosis of NCC, 30 were Ag-ELISA positive and 8 had highly suggestive lesions on CT-scan. As only study subjects with confirmed history of epilepsy and originating from Angónia district (considered a T. solium endemic area (Pondja et al., 2010)) were sent for CT-scanning, all study subjects had at least one minor and one epidemiological criteria.

4. Discussion

Based on the results of the study a total of 77 (51.0% (95% CI, 42.7–59.2)) and 38 (25.2% (95% CI, 18.5–32.9)) study subjects were diagnosed with definitive and probable diagnosis of NCC, respectively. This is the first study on NCC in Angónia district and the results provide the evidence that people living in rural areas of Tete province, where T. solium is wide spread, are suffering. A high proportion of study subjects with NCC was expected, as most of them were Ag-ELISA positive, highly suggestive lesions of NCC were prevalent and only subjects with epilepsy were sent for CT-scanning. The proportion of study subjects with NCC was similar to the proportion in the study on NCC in Burkina Faso by Millogo et al. (2012) but higher than the proportion of the imaging study carried out in Tanzania by Winkler et al. (2009a). Yet, in the latter study, results were based on hospital records only, which may provide an explanation for the difference. First of all, people living in remote areas have limited or no access to health care systems. Among those who have access, only the ones with severe symptoms are usually referred to a hospital (Mbuba et al., 2012), hence results based on hospital records might not provide the true picture. The systematic review on the frequency of NCC among people with epilepsy reported a proportion of 29% (95% CI, 22.9–35.5). This result should be interpreted with caution as it was based on 13 studies, of which only the study carried out in Tanzania was included for Africa (Ndimubanzi et al., 2010). In the present study more than 15% (95% CI, 12.8–16.2) of the study subjects were Ag-ELISA positive. The results of the multiple regression analysis indicated that males had a higher risk for a positive T. solium Ag-ELISA test in comparison to females. Absence of latrines at household level was an additional risk factor for Ag-ELISA positivity. These results are in accordance with findings in studies in Tanzania by Mwanjali et al. (2013), Senegal by Secka et al. (2011) and Burkina Faso by Carabin et al. (2009) but higher compared to other studies from West Africa (Carabin et al., 2009; Nguekam et al., 2003). Angónia district is considered a highly endemic area for cysticercosis. Pondja et al. (2010) carried out a study on porcine cysticercosis in the same area and found 35% (95% CI, 22.1–66.7) of the sampled pigs Ag-ELISA positive. Pigs were free roaming, meat inspection was absent and pork was commonly consumed by people. Latrines were accessible to pigs and no awareness of how the infection is transmitted or ways to control it were present among the population (Pondja et al., 2010).

In the present study the estimated LPE was 8.8% (95% CI, 7.5–10.2). This result was twice as high as the recently estimated LPE in rural Burkina Faso (4.5%) (Nitiema et al., 2012). The LPE in the present was also higher compared to the results of the systematic review on the prevalence of epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa, where the LPE ranged from 0% to 3.4% (Paul et al., 2012). Many studies on epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa are hospital based and may therefore not reflect the true disease burden. Health facilities in rural endemic areas are often not easily accessible hence patients may not have the possibility to seek specialized help which might generate a bias in the prevalence of epilepsy (Ndimubanzi et al., 2010; Preux and Druet-Cabanac, 2005; Winkler et al., 2009b). Furthermore in Africa, epilepsy is often believed to be linked to supernatural forces which further aggravate stigmatization, marginalization and exclusion of suffering people. This might further contribute to a lower percentage of people with epilepsy wanting to seek help at a health care facility (Atadzhanov et al., 2010; Jilek-Aall et al., 1997).

The brain CT-scan results revealed that more than half of the study subjects had lesions highly suggestive of NCC. Similar proportions were found in a study in South Africa (Vanas and Joubert, 1991). Moreover more than two thirds of the subjects with a positive CT-scan were Ag-ELISA positive. These results are in line with the studies carried out in Cameroon and Tanzania by Nguekam et al. (2003) and Mwanjali et al. (2013), respectively. Finally, the results presented are in accordance with the results of a WHO-commissioned review, where epilepsy was the most common manifestation observed in people with NCC (Carabin et al., 2011).

There are a number of limitations to this study. The study population did not reflect the gender distribution as our study population was predominantly female. Especially the male working class was underrepresented as at the time where the study was implemented the men were working, due to the economic instability of their country, in the neighboring countries Malawi and Zambia. Furthermore in the area where the study was carried out, more than 16% of families were monoparental with a woman as head of the family (Direcção Distrital de Agricultura de Angónia, 2005), partly explaining the larger proportion of females available for the study. As the EITB test was not available the Ag-ELISA test was used to measure current infection. Hence one major criteria of the Del Brutto et al. (2001) criteria for diagnosis of NCC had to be modified, namely the EITB test was replaced by Ag-ELISA. The aim of this study was not to estimate the prevalence of epilepsy, hence all study subjects with a history of epilepsy were sent for brain CT-scannig. This choice might have led to an overestimation of the study subjects with probable NCC as the diagnostic criteria included also study subjects with a positive Ag-ELISA and with a history of epilepsy without signs of an abnormal CT-scan.

5. Conclusions

This is the first study on NCC among study subjects with confirmed history of epilepsy in a remote, rural district of Mozambique. Findings of this study revealed a high proportion of NCC among people with epilepsy of Angónia district and support the idea that NCC is a cause of epilepsy in Africa. The parasite T. solium is present in the area and is causing morbidity among the affected population. Many cases of epilepsy could potentially be prevented if strategies to control T. solium cysticercosis were available. Hence identification of subjects with NCC and determination of effective strategies for prevention and control of T. solium cysticercosis are necessary to reduce the burden of disease among the inhabitants of the area. As T. solium cysticercosis has shown to be an important public health issue in Angónia district, further studies are warranted to ascertain these findings in other parts of the country.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the Serviços Provinciais de Pecuária de Tete, Serviços Distritais de Agricultura de Angónia, Estação Zootécnica de Angónia, the community authorities and the study participants for their valuable co-operation.

The study was supported by the Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA) with its two projects: CESA-project (Cross-disciplinary risk assessment of Cysticercosis in Eastern and Southern Africa), funded by, file no. 104.Dan.8.L.721 and SLIPP-project (Securing rural Livelihoods through Improved smallholder Pig Production in Mozambique and Tanzania), funded by, file no. 09–007LIFE.

References

- Atadzhanov M, Haworth A, Chomba EN, Mbewe EK, Birbeck GL, 2010. Epilepsy-associated stigma in Zambia: what factors predict greater felt stigma in a highly stigmatized population? Epilepsy Behav 19, 414–418, 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt JRA, Geerts S, Dedeken R, Kumar V, Ceulemans F, Brijs L, Falla N, 1992. A monoclonal antibody-based ELISA for the detection of circulating excretory antigens in Taenia saginata cysticercosis. Int. J. Parasitol 22, 471–477, 10.1016/0020-7519(92)90148-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carabin H, Millogo A, Praet N, Hounton S, Tarnagda Z, Ganaba R, Dorny P, Nitiema P, Cowan LD, Faso E, 2009. Seroprevalence to the antigens of Taenia solium cysticercosis among residents of three villages in Burkina Faso: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis 3, e555, 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carabin H, Ndimubanzi PC, Budke CM, Nguyen H, Qian YJ, Cowan LD, Stoner JA, Rainwater E, Dickey M, 2011. Clinical manifestations associated with neurocysticercosis: a systematic review. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis 5, e1152, 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chromy JR, 2008. Probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling In: Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, California, USA, pp. 620–622. [Google Scholar]

- Del Brutto OH, 2012. Diagnostic criteria for neurocysticercosis, revisited. Pathog. Global Health 106, 299–304, 10.1179/2047773212Y.0000000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Brutto OH, Del Brutto VJ, 2012. Calcified neurocysticercosis among patients with primary headache. Cephalalgia 32, 250–254, 10.1177/0333102411433043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Brutto OH, Garcia HH, 2013. Neurocysticercosis. Handbook of clinical neurology 114, 313–325. 10.1016/b978-0-444-53490-3.00025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Brutto OH, Rajshekhar V, White AC, Tsang VCW, Nash TE, Takayanagui OM, Schantz PM, Evans CAW, Flisser A, Correa D, Botero D, Allan JC, Sarti E, et al. , 2001. Proposed diagnostic criteria for neurocysticercosis. Neurology 57, 177–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewhurst F, Dewhurst MJ, Gray WK, Aris E, Orega G, Howlett W, Warren N, Walker RW, 2013. The prevalence of neurological disorders in older people in Tanzania. Acta Neurol. Scand 127, 198–207, 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2012.01709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Direcção Distrital de Agricultura de Angónia (2005). Perfil do Distrito de Angónia, Provincia de Tete. Relatório Anual De Actividades. Ministério da Administração Estatal, República de Moçambique, Moçambique, p. 63. [Google Scholar]

- Dorny P, Phiri IK, Vercruysse J, Gabriel S, Willingham AL, Brandt J, Victor B, Speybroeck N, Berkvens D, 2004. A Bayesian approach for estimating values for prevalence and diagnostic test characteristics of porcine cysticercosis. Int. J. Parasitol 34, 569–576, 10.1016/j.ijpara.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorny P, Vercammen F, Brandt J, Vansteenkiste W, Berkvens D, Geerts S, 2000. Sero-epidemiological study of Taenia saginata cysticercosis in Belgian cattle. Vet. Parasitol 88, 43–49, 10.1016/s0304-4017(99)00196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar A, Weidenheim KM, 2002. The pathology of neurocysticercosis In: Singh G, Prabhakar S (Eds.), Taenia Solium Cysticercosis. From Basic to Clinical Science CAB International, Oxon, UK, pp. 289–305. [Google Scholar]

- Fabiani S, Bruschi F, 2013. Neurocysticercosis in Europe: still a public health concern not only for imported cases. Acta Trop 128, 18–26, 10.1016/j.acta.tropica.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RS, Boas WV, Blume W, Elger C, Genton P, Lee P, Engel J, 2005. Epileptic seizures and epilepsy: definitions proposed by the International League against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE). Epilepsia 46, 470–472, 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.66104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel S, Blocher J, Dorny P, Abatih EN, Schmutzhard E, Ombay M, Mathias B, Winkler AS, 2012. Added value of antigen ELISA in the diagnosis of neurocysticercosis in resource poor settings. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis 6, e1851, 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ILAE International League Against Epilepsy, 1993. Guidelines for epidemiologic studies on epilepsy. Commission on Epidemiology and Prognosis, International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia 34, 592–596, 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jilek-Aall L, Jilek M, Kaaya J, Mkombachepa L, Hillary K, 1997. Psychosocial study of epilepsy in Africa. Soc. Sci. Med 45, 783–795 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbuba CK, Ngugi AK, Fegan G, Ibinda F, Muchohi SN, Nyundo C, Odhiambo R, Edwards T, Odermatt P, Carter JA, Newton CR, 2012. Risk factors associated with the epilepsy treatment gap in Kilifi, Kenya: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol 11, 688–696, 10.1016/s1474-4422(12)70155-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millogo A, Nitiema P, Carabin H, Boncoeur-Martel MP, Rajshekhar V, Tarnagda Z, Praet N, Dorny P, Cowan L, Ganaba R, Hounton S, Preux P-M, Cisse R, 2012. Prevalence of neurocysticercosis among people with epilepsy in rural areas of Burkina Faso. Epilepsia 53, 2194–2202, 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03687.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwanjali G, Kihamia C, Kakoko DVC, Lekule F, Ngowi H, Johansen MV, Thamsborg SM, Willingham AL, 2013. Prevalence and risk factors associated with human Taenia Solium infections in Mbozi District, Mbeya Region, Tanzania. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis 7, e2102, 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndimubanzi PC, Carabin H, Budke CM, Nguyen H, Qian YJ, Rainwater E, Dickey M, Reynolds S, Stoner JA, 2010. A systematic review of the frequency of neurocyticercosis with a focus on people with epilepsy. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis 4, e870, 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguekam JP, Zoli AP, Zogo PO, Kamga ACT, Speybroeck N, Dorny P, Brandt J, Losson B, Geerts S, 2003. A seroepidemiological study of human cysticercosis in West Cameroon. Trop. Med. Int. Health 8, 144–149, 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngugi AK, Bottomley C, Kleinschmidt I, Sander JW, Newton CR, 2010. Estimation of the burden of active and life-time epilepsy: a meta-analytic approach. Epilepsia 51, 883–890, 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitiema P, Carabin H, Hounton S, Praet N, Cowan LD, Ganaba R, Kompaore C, Tarnagda Z, Dorny P, Millogo A, EFECAB, 2012. Prevalence case-control study of epilepsy in three Burkina Faso villages. Acta Neurol. Scand 126, 270–278, 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2011.01639.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul A, Adeloye D, George-Carey R, Kolcic I, Grant L, Chan KY, 2012. An estimate of the prevalence of epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic analysis. J. Global Health 2, 20405, 10.7189/jogh.02.020405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pondja A, Neves L, Mlangwa J, Afonso S, Fafetine J, Willingham AL 3rd, hamsborg SM, Johansen MV, 2015. Incidence of porcine cysticercosis in Angonia District, Mozambique. Prev. Vet. Med 118, 493–497, 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pondja A, Neves L, Mlangwa J, Afonso S, Fafetine J, Willingham AL III, hamsborg SM, Johansen MV, 2010. Prevalence and risk factors of porcine cysticercosis in Angonia District, Mozambique. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis 4, e594, 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praet N, Rodriguez-Hidalgo R, Speybroeck N, Ahounou S, Benitez-Ortiz W, Berkvens D, Van Hul A, Barnonuevo-Samaniego M, Saegerman C, Dorny P, 2010. Infection with versus exposure to Taenia solium: what do serological test results tell us? Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg 83, 413–415, 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preux P-M, Druet-Cabanac M, 2005. Epidemiology and aetiology of epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Neurol 4, 21–31, 10.1016/s1474-4422(04)00963-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quet F, Guerchet M, Pion SDS, Ngoungou EB, Nicoletti A, Preux P-M, 2010. Meta-analysis of the association between cysticercosis and epilepsy in Africa. Epilepsia 51, 830–837, 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman G, Sotelo J, Del Brutto O, Flisser A, Dumas M, Wadia N, Botero D, Cruz M, Garcia H, de Bittencourt PRM, Trelles L, Arriagada C, Lorenzana P, et al. , 2000. A proposal to declare neurocysticercosis an international reportable disease. Bull. World Health Organ 78, 399–406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secka A, Grimm F, Marcotty T, Geysen D, Niang AM, Ngale V, Boutche L, Van Marck E, Geerts S, 2011. Old focus of cysticercosis in a senegalese village revisited after half a century. Acta Trop 119, 199–202, 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serpa JA, White ACJ Jr., 2012. Neurocysticercosis in the United States. Pathog. Global Health 106, 256–260, 10.1179/2047773212y.0000000028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokal R, Rohlf F, 1995. Biometry: The Principles and Practice of Statistics in Biological Research, 3rd ed. W.H. Freeman, New York, pp. 887. [Google Scholar]

- Somers R, Dorny P, Nguyen VK, Dang TCT, Goddeeris B, Craig PS, Vercruysse J, 2006. Taenia solium taeniasis and cysticercosis in three communities in north Vietnam. Trop. Med. Int. Health 11, 65–72, 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegueu CK, Nguefack S, Doumbe J, Fogang YF, Mbonda PC, Mbonda E, 2013. The spectrum of neurological disorders presenting at a neurology clinic in Yaounde, Cameroon. Pan Afr. Med. J 14, 148, 10.11604/pamj.2013.14.148.2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanas AD, Joubert J, 1991. Neurocysticercosis in 578 black epileptic patients. S. Afr. Med. J 80, 327–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilhena M, Bouza M, 1994. Serodiagnóstica da cisticercose humana na cidade de Tete Mocambique. Rev. Med. Mocambique 5, 6–9, 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wayne DW, 1999. Biostatistics: A Foundation for Analysis in the Health Sciences, 7th ed. John Wiley & Sons, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler AS, Blocher J, Auer H, Gotwald T, Matuja W, Schmutzhard E, 2009a. Epilepsy and neurocysticercosis in rural Tanzania—an imaging study. Epilepsia 50, 987–993, 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler AS, Willingham AL, Sikasunge CS, Schmutzhard E, 2009b. Epilepsy and neurocysticercosis in sub-Saharan Africa. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr 121, 3–12, 10.1007/s00508-009-1242-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]