Abstract

The use of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) to control multiple pathogens that affect different crops was studied, namely, Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae in kiwifruit, Xanthomonas arboricola pv. pruni in Prunus and Xanthomonas fragariae in strawberry. A screening procedure based on in vitro and in planta assays of the three bacterial pathogens was successful in selecting potential LAB strains as biological control agents. The antagonistic activity of 55 strains was first tested in vitro and the strains Lactobacillus plantarum CC100, PM411 and TC92, and Leuconostoc mesenteroides CM160 and CM209 were selected because of their broad‐spectrum activity. The biocontrol efficacy of the selected strains was assessed using a multiple‐pathosystem approach in greenhouse conditions. L. plantarum PM411 and TC92 prevented all three pathogens from infecting their corresponding plant hosts. In addition, the biocontrol performance of PM411 and TC92 was comparable to the reference products (Bacillus amyloliquefaciens D747, Bacillus subtilis QST713, chitosan, acibenzolar‐S‐methyl, copper and kasugamycin) in semi‐field and field experiments. The in vitro inhibitory mechanism of PM411 and TC92 is based, at least in part, on a pH lowering effect and the production of lactic acid. Moreover, both strains showed similar survival rates on leaf surfaces. PM411 and TC92 can easily be distinguished because of their different multilocus sequence typing and random amplified polymorphic DNA profiles.

Keywords: bacterial plant diseases, Lactobacillus plantarum, Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae, Xanthomonas arboricola pv. pruni, Xanthomonas fragariae

1. INTRODUCTION

Increased global trade, together with climate change and the limitations in plant protection products, has favoured the emergence and establishment of new plant diseases which, in turn, cause significant crop losses (Lamichhane et al., 2015; Yáñez‐López et al., 2012). Fruit production, for instance, is threatened by several bacterial plant diseases such as the bacterial canker of kiwifruit caused by Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae (Psa), the bacterial spot of stone fruits caused by Xanthomonas arboricola pv. pruni (Xap) and the angular leaf spot of strawberry caused by Xanthomonas fragariae (Xf) (Donati et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2016; Lamichhane, 2014). The European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO) lists Psa, Xap and Xf as quarantine organisms.

Managing these diseases mainly relies on preventive applications of bactericides containing copper compounds or antibiotics (Cameron & Sarojini, 2014; Lamichhane, 2014). However, the selection of resistant pathogen populations and phytotoxicity are the main drawbacks to this practice (Lalancette & McFarland, 2007; McManus, Stockwell, Sundin, & Jones, 2002). Overall, reliance on conventional pesticides needs to be reduced and an integrated pest management (IPM) framework implemented (Lamichhane et al., 2015). The plant defence elicitor acibenzolar‐S‐methyl (ASM) has been reported as being a potential alternative compound for managing bacterial canker of kiwifruit (Cellini et al., 2014) and angular leaf spot of strawberry (Braun & Hildebrand, 2013). Likewise, chitosan exhibits antimicrobial activity and acts as an elicitor of plant defence mechanisms, making it a potential alternative agent for managing bacterial canker of kiwifruit (Cameron & Sarojini, 2014). Nevertheless, phytotoxicity and a high variability in the response in host plants in the field have been reported, which raises questions about their feasibility in crop protection (Reglinski et al., 2013). Therefore, interest in selecting beneficial microorganisms with which to develop biological control agents (BCAs) has increased as a result of microbial biopesticides being an indispensable and powerful tool in IPM (Matyjaszczyk, 2015). While strains of bacteria, fungi and viruses to manage plant diseases and pests are now commercially available (Matyjaszczyk, 2015; Montesinos & Bonaterra, 2017), because of the influence biotic and abiotic factors have, the efficacy of the biological products may vary between trials or decrease in field conditions (Sundin, Werner, Yoder, & Aldwinckle, 2009). Such limitations have stimulated the search for novel strains of microorganisms that have a broad spectrum of antagonistic activity against plant pathogens. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are an interesting group often found in a plant‐associated microbiome (Trias, Bañeras, Badosa, & Montesinos, 2008; Zwielehner et al., 2008).

LAB are good candidates to develop microbial biopesticides with, because they include some strains which have been categorised by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as Generally Regarded as Safe and by the European Food Safety Authority as having Qualified Presumption of Safety. Furthermore, many LAB strains show antimicrobial activity thanks to the production of active metabolites such as organic acids, bacteriocins and several inhibitory bioactive compounds (Reis, Paula, Casarotti, & Penna, 2012). LAB have been widely reported as being biopreservatives of vegetables and fruits, inhibiting the growth of foodborne bacterial pathogens and spoilage fungi (Crowley, Mahony, & Van Sinderen, 2013; Trias, Bañeras, Badosa, & Montesinos, 2008; Trias, Bañeras, Montesinos, & Badosa, 2008). In addition, some LAB strains have also been reported as being potential BCA against several bacterial plant pathogens (Roselló et al., 2013; Tsuda et al., 2016; Visser, Holzapfel, Bezuidenhout, & Kotze, 1986).

BCA must be carefully selected because not all species or strains confer plant protection against pathogens. Screening strategies enabling the selection of strains with pathogen suppressive activity include in vitro antagonism tests and the assessment of infection prevention in detached plant organs and whole plants (Haidar et al., 2016; Köhl, Postma, Nicot, Ruocco, & Blum, 2011; Roselló et al., 2013). Moreover, keen commercial interest in LAB has fuelled studies to typify the most promising strains, as their identification and characterisation is a requirement for BCA registration. Typing techniques are based on DNA analysis and two of the most commonly used are multilocus sequence typing (MLST) (de las Rivas et al., 2006; Tanganurat et al., 2009) and random amplified polymorphic DNA‐PCR (RAPD‐PCR) (López, Torres, & Ruiz‐Larrea, 2008).

The aims of the present study were fourfold: (a) screen plant‐associated LAB using in vitro tests and select antagonistic strains with broad‐spectrum activity against Psa, Xap and Xf, (b) assess the biocontrol efficacy of the selected strains in preventing infections by the three pathogens in potted plants (kiwifruit, Prunus and strawberry) in the greenhouse, (c) compare the biocontrol performance of the selected strains to reference products in semi‐field and field experiments and (d) characterise the selected strains in regards to the mechanisms involved in the in vitro antibacterial activity against Psa, Xap and Xf and MLST and RAPD‐PCR profiling.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Bacterial strains and culture conditions

A total of 55 plant‐associated LAB isolates from the culture collection of the Institute of Food and Agricultural Technology and Center for Innovation and Development of Plant Health (INTEA‐CIDSAV) were selected for this study (Table 1). Spontaneous rifampicin resistant mutants of wild‐type Lactobacillus plantarum PM411 and TC92 (PM411R and TC92R) were used in the plant colonisation studies (Roselló et al., 2013).

Table 1.

Lactic acid bacteria and bacterial plant pathogen strains used in this study

| Species | Code straina | Host | Geographical origin | Growth mediumb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactic acid bacteriac | ||||

| Lactobacillus plantarum | AC58, AC59, AC73, AC81, AC84 | Aubergine | Spain | MRS |

| BC24, BC30, BC37, BC50, BC66 | Chard | Spain | MRS | |

| CC31, CC100, CC121 | Cucumber | Spain | MRS | |

| CC70, CC85, CC93 | Cabbage | Spain | MRS | |

| CM450 | Courgette | Spain | MRS | |

| CM466 | Persimmon | Spain | MRS | |

| FC248, FC534 | Fig | Spain | MRS | |

| NC568 | Loquat | Spain | MRS | |

| PC40, PC49, PC67 | Potato | Spain | MRS | |

| PM314, PM340, PM411, PM411Rd | Pear | Spain | MRS | |

| RC526 | Blackberry | Spain | MRS | |

| TC26, TC28, TC35, TC41, TC43, TC44, TC46, TC54, TC60, TC69, TC71, TC92, TC92Rc, TC97, TC101, TC102, TC110, TM106 | Tomato | Spain | MRS | |

| Lactobacillus pentosus | SE217, SE294, SE304, SE307 | Soya beans | Spain | MRS |

| BM305 | Broccoli | Spain | MRS | |

| Leuconostoc mesenteroides | CM160 | Cherry | Spain | MRS |

| CM209 | Lettuce | Spain | MRS | |

| PM366 | Peach | Spain | MRS | |

| Lactococcus lactis | SE303 | Soya beans | Spain | MRS |

| Non‐identified | FC560 | Fig | Spain | MRS |

| Bacterial plant pathogens | ||||

| Psa | CFBP7286, CFBP7286‐GFPuve | Actinidia chinensis | Italy | Luria‐Bertani |

| NCPPB3739 | Actinidia deliciosa | Japan | Luria‐Bertani | |

| IVIA 3700‐1f | A. deliciosa | Portugal | Luria‐Bertani | |

| Xap | CFBP3894 | Prunus salicina | New Zealand | Luria‐Bertani |

| CFBP5563 | Prunus persica | France | Luria‐Bertani | |

| Xf | IVIA XF349‐9Af | Fragaria vesca | Spain | B medium |

| CECT549 | Fragaria chiloensis var. ananassa | USA | B medium | |

CECT: Colección Española de Cultivos Tipo; CFBP: La Collection Française de Bactéries Phytopathogènes; INTEA‐CIDSAV: Institute of Food and Agricultural Technology and Center for Innovation and Development of Plant Health; IVIA: Instituto Valenciano de Investigaciones Agrarias; LAB: lactic acid bacteria; NCPPB: National Collection of Plant Pathogenic Bacteria; Psa: Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae; Xap, Xanthomonas arboricola pv. pruni; Xf, Xanthomonas fragariae.

CFBP (Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA), France); CECT (Valencia, Spain); IVIA (Valencia, Spain); NCPPB (Fera, UK).

MRS (de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe), B medium (Hazel & Civerolo, 1980).

INTEA‐CIDSAV culture collection (Roselló et al., 2013; Trias, Bañeras, Badosa, & Montesinos, 2008; Trias, Bañeras, Montesinos, & Badosa, 2008). LAB strains were identified at species level based on 16S rDNA sequences. L. plantarum “group” was confirmed using species‐specific primers (PLANT1/LOWLAC) (Chagnaud, Machinis, Coutte, Marecat, & Mercenier, 2001) by PCR amplification. Positive isolates for species‐specific PCR were then tested by multiplex PCR in a second step for the identification of L. plantarum, L. paraplantarum and L. pentosus with recA gene‐based primers paraF, pentF, planF and pREV (Torriani, Felis, & Dellaglio, 2001).

Spontaneous mutants of L. plantarum PM411 and TC92 strains resistant to rifampicin.

Courtesy of Dr. F. Spinelli, Department of Agricultural and Food Sciences, University of Bologna, Italy (Spinelli, Donati, Vanneste, Costa, & Costa, 2011).

Courtesy of Dra M. M. Lopez, IVIA, Valencia, Spain.

Three strains of P. syringae pv. actinidiae (Psa) and two strains of Xap and Xf were used as target bacteria in the in vitro antagonism tests and biocontrol efficacy assays (Table 1). Psa CFBP7286‐GFPuv, which is resistant to kanamycin, was used for the colonisation studies in kiwifruit plants (Spinelli et al., 2011).

Cultures were prepared for routine use from the isolates preserved at −80°C. LAB were grown on de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) at 23°C for 48 h. Psa and Xap were grown on Luria‐Bertani agar at 23°C for 24 hr and Xf was grown on B medium (Hazel & Civerolo, 1980) at 23°C for 24 hr. Bacterial suspensions were prepared in distilled water at 1‐5 x 108 colony forming units (CFU)/mL.

2.2. Plant material and greenhouse conditions

Two‐year‐old kiwifruit plants and 15‐ to 30‐day‐old kiwifruit plantlets (Actinidia chinensis var. deliciosa cv. Hayward), 15‐ to 30‐day‐old Prunus amygdalus × Prunus persica plantlets (cv. GF‐677), and cold‐stored strawberry plants (Fragaria × ananassa cv. Darselect) were obtained from commercial nurseries (SolJardí, Jafre, Spain; Vitroplant, Cesena, Italy; Agromillora Iberica, Barcelona, Spain; and Planasa, Valtierra, Spain, respectively). Potted plants with about 8 to 10 leaves per plant were used and were kept in a greenhouse at 26 ± 2°C, 60 ± 10% relative humidity (RH) and a 16:8 hr light:dark photoperiod. Standard nitrogen‐phosphate‐potassium (NPK) fertilisation and irrigation, as well as insecticide and miticide sprays were applied. Plants inoculated with Psa, Xap or Xf were maintained in a class II greenhouse (i.e., an EPPO A2 level quarantine biosafety greenhouse).

2.3. In vitro antagonistic activity

The antagonistic activity of 55 LAB isolates was assayed in vitro on Psa (NCPPB3739 and IVIA 3700‐1), Xap (CFBP3894 and CFBP5563) and Xf (IVIA XF349‐9A and CECT549). The experiment was performed twice using two procedures. One assay was carried out with the agar spot test in lactose‐bromocresol purple agar (LBP) as in Trias, Bañeras, Badosa, and Montesinos (2008), albeit with some modifications. Specifically, LBP soft agar (0.7% agar) was mixed with Psa or Xap suspension, while B medium soft agar was mixed with Xf suspension. For the other assay, 5‐mm‐in‐diameter discs cut from 24‐h‐old cultures of LAB isolates on MRS agar were deposited on the surface of plates containing cultures of the target pathogen. 0.5 mL of the target pathogen suspension at 5 × 107 CFU/mL was mixed in 4.5 mL of Luria‐Bertani (Psa and Xap) or with B medium (Xf) soft agar (0.7% agar) and overlaid on the plate containing the same media. Plates were incubated at 23°C, and the diameter of the zone of inhibition was measured after 24 and 48 hr.

2.4. Biocontrol efficacy assays under greenhouse conditions

A total of five LAB isolates (L. plantarum CC100, PM411, TC92 and Leuconostoc mesenteroides CM160 and CM209) were evaluated. Potted two‐year‐old kiwifruit plants, Prunus, and strawberry plants were sprayed to runoff with a 108 CFU/mL suspension of LAB cells using a hand‐sprayer (Herkules, Nuair, Robassomero, Italy). The plants were then kept in plastic bags in the greenhouse in order to reach high RH conditions. After 24 hr, plants were inoculated with a suspension of the corresponding pathogen at 1–5 × 108 CFU/mL (IVIA 3700‐1 of Psa, CFBP5563 of Xap or CECT549 of Xf). The pathogen suspensions were mixed with diatomaceous earth (1 mg/mL) and applied to runoff using a hand‐sprayer. Once again, the plants were covered with plastic bags for 24 hr and kept in a class II greenhouse. Streptomycin‐treated (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) (100 mg/L) and water‐treated plants were included as controls. Disease incidence was calculated as the percentage of infected leaves and was determined in each replicate at 15 to 21 days post inoculation.

2.5. Survival of L. plantarum PM411 and TC92 on leaves

The potted plants were sprayed to runoff with a 108 CFU/mL cell suspension of PM411R (in the case of strawberry and 15‐ to 30‐day‐old kiwifruit plantlets) or TC92R (Prunus), then covered with plastic bags and maintained in the greenhouse as described above. The monitoring of PM411R and TC92R population levels was performed as Roselló, Francés, Daranas, Montesinos, and Bonaterra (2017) described. Three leaves were taken from each replicate at 0, 1, 2, 5, 8 and 10 days post inoculation. The population levels of PM411R and TC92R were expressed as Log10 CFU per leaf.

2.6. Effect of L. plantarum PM411 on Psa survival in kiwifruit plants

Potted kiwifruit plants (15‐ to 30‐day‐old plantlets) were sprayed with a 108 CFU/mL cell suspension of PM411, covered with plastic bags and maintained in the greenhouse as described above. After 24 hr, the plants were inoculated with Psa suspension at 1–5 × 108 CFU/mL (CFBP7286‐GFPuv) to runoff using a hand‐sprayer, covered with plastic bags and maintained in the greenhouse. Streptomycin‐treated (Sigma) (100 mg/L) and water‐treated plants were included as controls. To monitor epiphytic and endophytic Psa populations, three leaves per replicate were sampled at 1 and 4 days post inoculation. Leaves were weighed and vigorously homogenised in 20 mL of 50‐mM sterile phosphate buffer and 0.1% peptone for 5 min to collect the epiphytic population. The same leaves were also used to assess the endophytic population consistent with Cellini et al. (2018). Appropriate dilutions of epiphytic and endophytic samples were seeded onto Luria‐Bertani agar plates amended with 100 μg/mL of kanamycin (Sigma) to select CFBP7286‐GFPuv and 100 μg/mL of cycloheximide (Sigma) to avoid fungal growth. Plates were incubated at 23°C for 48 hr, and the green fluorescent colonies were counted under UV light. The epiphytic and endophytic population levels of Psa were expressed as Log10 CFU per leaf or g, respectively.

2.7. Biocontrol efficacy assays under semi‐field conditions

The efficacy of L. plantarum PM411 and TC92 in controlling Psa, Xap and Xf was studied in semi‐field assays and compared to reference products. The semi‐field assays consisted of treatment applications in the field and keeping plants there for 7 days before being transported to a class II greenhouse for pathogen inoculation.

Potted two‐year‐old kiwifruit plants were taken to an experimental orchard located in Zevio (Verona, Italy). The treatments administered were: (a) PM411 cell suspension at 108 CFU/mL prepared as described above, (b) Bacillus amyloliquefaciens D747 (Amylo‐X, 25% w/w a.i., 5 × 1010 CFU/g; Biogard, Monza Brianza, Italy) at 0.375 g a.i. L−1, (c) copper oxide (Nordox, 75% w/w a.i.; Comercial Química Massó, Barcelona, Spain) at 0.45 g a.i. L−1.

Potted Prunus and strawberry plants were taken to the experimental orchard located at the Mas Badia Agricultural Experiment Station (Girona, Spain). The treatments performed were: (a) TC92 or PM411 cell suspension at 108 CFU/mL prepared as described above, (b) Bacillus subtilis QST713 (Serenade Max, 15.67% w/w a.i.; Bayer Crop Science, Monheim am Rhein, Germany) at 0.55 g a.i. L−1, (c) chitosan (Biorend, 2.5% v/v a.i.; Bioagro, Santiago, Chile) at 7.5 g a.i. L−1, (d) ASM (Bion, 50% w/w a.i.; Syngenta, Basel, Switzerland) at 0.075 g a.i. L−1, (e) copper hydroxide (Kocide, 35% w/w a.i; Certis, Elche, Spain) at 1.05 g a.i. L−1 and (f) kasugamycin (Kasumin, 8% w/w a.i; Lainco, Barcelona, Spain) at 0.16 g/L. In all the experiments, water‐treated plants were included as controls. All the treatments, except for kasugamycin, were applied twice, 7 and 1 days before inoculation, using a hand‐sprayer to runoff.

Plants were spray‐inoculated with the corresponding pathogen suspension at 108 CFU/mL (Psa CFBP7286, Xap CFBP5563, Xf CECT549) as described in the greenhouse experiments. After inoculation, plants were covered with plastic bags for 48 hr and maintained in the class II greenhouse. The disease incidence was determined as described earlier (see greenhouse experiments) for each replicate at 15–21 days post inoculation.

2.8. Biocontrol efficacy assays in orchard conditions

The field experiment was carried out in 2017 at a commercial orchard (A. chinensis var. deliciosa, cv. Hayward) located in Sarna, close to Faenza (Emilia Romagna, Italy). The disease had been present in this orchard in previous years with a moderate pressure. Standard cultural management (i.e., fertigation, green and winter pruning, thinning and assisted pollination) was adopted. For each plant (experimental design explained below), four shoots without Psa symptoms were selected and tagged at the beginning of the experiment. The treatments performed were: (a) PM411 cell suspension at 108 CFU/mL prepared as described above, (b) B. amyloliquefaciens D747 (Amylo‐X 5 × 1010 CFU/g) at 0.375 g a.i. L−1, and (c) copper oxide (Nordox) at 0.45 g a.i. L−1. Water‐treated plants were included as controls. All the treatments were applied every 14 days or after each rainfall (≥4 mm of rain), in the case the rain event occurred at 7 or more days after the treatment. Copper applications started at bud break (phenological Biologische Bundesanstalt, Bundessortenamt und CHemische Industrie (BBCH) 03) and were repeated until fruit grew to 30% of the final size (BBCH 73). BCA applications were performed at 10, 50 and 100% of blooming and were repeated until BBCH 73 was reached. Psa incidence was assessed twice during the season, with the second assessment taking place once disease progression had been halted and was calculated as the percentage of symptomatic leaves on 20 shoots per repetition. Psa symptomatology was confirmed by molecular identification following Gallelli, Talocci, L'aurora, and Loreti (2011).

2.9. Characterising PM411 and TC92 strains

The role the different metabolites played on the antibacterial activity of PM411 and TC92 strains against target pathogens was studied together with a genotypic characterisation.

2.9.1. Metabolite profiling

Agar diffusion assays using cell‐free supernatants (CFSs) were performed. PM411 and TC92 strains were grown in MRS broth for 24 hr at 30°C with shaking (100 rpm). CFS were obtained by centrifugation (10,000 g for 10 min) (5,810 R; Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) and were filtered (Whatman FP30/0.45; Millipore, Bedford, MA). 20 μL of CFS was deposited on the surface of plates containing cultures of the target pathogens (Psa IVIA 3700‐1, Xap CFBP3894, and Xf IVIA XF349‐9A) prepared as described above (see in vitro antagonism tests, Luria‐Bertani for Psa and Xap and B medium for Xf). Plates were incubated at 23°C, and the diameter of zone of inhibition was examined at 24 and 48 hr. Fractions of CFS were exposed to different treatments (neutralised CFS, and neutralised CFS treated with proteinase K, trypsin, α‐chymotrypsin or catalase) as described by Trias, Bañeras, Montesinos, and Badosa (2008), and the antimicrobial activity was assessed by agar diffusion assay (as described above). Three independent replicates for each CFS fraction were performed. Lactic acid was quantified in CFS using an Enzytec D‐/L‐Lactic Acid commercial kit (Boehringer Mannheim/R‐Biopharm AG, Darmstadt, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions. 1:10 diluted CFS with redistilled water was used for the measurement. Two experiments were carried out with three independent replicates.

2.9.2. Molecular characterisation of PM411 and TC92

DNA extraction. Genomic DNA from cell suspensions at 108 CFU/mL of the 45 L. plantarum isolates (INTEA‐CIDSAV culture collection, Table 1) was extracted as described by Llop, Caruso, Cubero, Morente, and López (1999). The concentration and purity of the DNA was assessed using a NanoDrop ND‐1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

PCR amplifications and conditions. Amplification mixtures and PCR conditions for MLST and RAPD‐PCR analysis are described in Table 2. The amplification products were separated by electrophoresis on a 1.5% (w/v) agarose gel in 1× Tris‐acetate Disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate dihydrate (EDTA) and stained with Sybr Safe (SYBR Safe, Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Gel images were captured with an imaging system (FX‐20M; Vilvert, Lourmat, France).

MLST analysis. The housekeeping genes encoding the following proteins were chosen for analysis: phosphoglucomutase (pgm), D‐alanine‐D‐alanine ligase (ddl), B subunit of DNA gyrase (gyrB), ATPase subunit of the phosphoribosylaminoimidazole carboxylase (purK1), glutamate dehydrogenase (gdh) and DNA mismatch repair protein (mutS). The amplification and sequencing primers used have been previously described by de las Rivas et al. (2006), except for the gdh gene where the primers were designed in this work (gdhF 5′‐GGTTACACCCATCCGTTAAT‐3′ and gdhR 5′‐TTCTTCAAAAGTCCAGTCA‐3′, 901‐bp fragment). Amplification products were purified with a desalting and concentrating DNA solutions kit QIAEX (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany) for direct sequencing using the Automatic Sequencer 3730XL (Macrogen, Seoul, South Korea). Sequence alignments and comparisons were performed using a BioEdit Sequencing Editor (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/bioedit/bioedit.html). For each gene, the sequences obtained in this study from the 45 L. plantarum isolates (Table 1) were compared to each other and to the sequences of 26 L. plantarum isolates previously reported (de las Rivas et al., 2006; Tanganurat et al., 2009). Allele numbers were assigned following the codes previously described (de las Rivas et al., 2006; Tanganurat et al., 2009). New allele sequences were deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers KT247498 (allele 4 pgm), KT247499 (allele 7 ddl), KT247496 (allele 9 purK1), KT247497 (allele 10 purK1), KT247501 (allele 11 gdh) and KT247500 (allele 9 mutS). Each strain was defined by an allele profile or sequence type (ST) as described in de las Rivas et al. (2006).

RAPD‐PCR analysis. PCR amplification of the 45 L. plantarum isolates was carried out. The primers P3 (Tailliez, Tremblay, Dusko Ehrlich, & Chopin, 1998), Inva1 (Rahn et al., 1992), 512Fb (Holt & Cote, 1998), P4 and P7 (Di Cagno et al., 2010), with arbitrarily chosen sequences, were used singly in separate reactions. Pattern analyses were performed with Image Lab version 4.1 software (Bio‐Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Table 2.

Amplification mixtures and PCR conditions

| PCR approach | Amplification mixturea | PCR conditionsb |

|---|---|---|

| MLST | 1× PCR buffer, 2.5‐mM MgCl2, 0.2‐mM dNTPs, 0.2 μM each primer, 1 U Taq and 20‐ng DNA (reaction vol, 25 μL) | 95°C for 10 min; 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 54°C (gdh) or 48°C (pgm, ddl, gyrB, purK1, mutS) for 60 s, 72°C for 60 s; and elongation 72°C for 10 min. |

| RAPD‐PCR | 1× PCR buffer, 1.5‐mM MgCl2, 0.2‐mM dNTPs, 0.2 μM each primer, 3.75 U Taq, and 50‐ng DNA (reaction vol, 25 μL) | For P3 and P4: 94°C for 3 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 36°C for 2 min, 72°C for 2 min; and elongation at 72°C for 2 min. For 512Fb, Inva1 and P7: 94°C for 4 min; 45 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 35°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min; and elongation at 72°C for 5 min. |

dNTPs: deoxynucleotides; MLST: multilocus sequence typing; RAPD‐PCR: random amplified polymorphic DNA‐PCR.

dNTPs (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA); primers (Sigma Aldrich, Barcelona, Spain); Taq, Taq DNA polymerase (Biotools, Madrid, Spain for MLST and Invitrogen for RAPD‐PCR).

PCR was carried out in a GeneAmp PCR system 9,700 (Applied Biosystems).

2.10. Experimental designs and data analysis

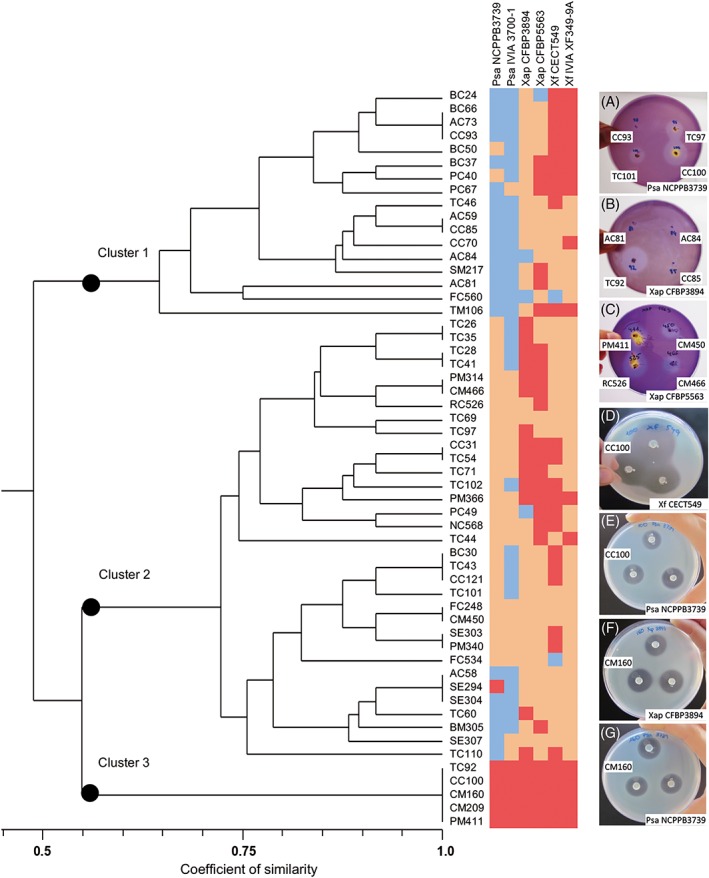

In vitro antagonism tests consisted of three independent replicates of each LAB and were performed twice. The diameters of the zones of inhibition were transformed into binary data (“1” for presence and “0” for absence of inhibition zone) for hierarchical cluster analysis. The simple matching coefficient of similarity using the unweighted pair group method with the arithmetic average (UPGMA) as the cluster algorithm was used (Numerical Taxonomy System program package NTSYSpc, Exeter Software, New York City, NY). For each target pathogen strain, a value of “0” in both assays was considered as no inhibition activity, a value of “1” in only one assay was considered as moderate inhibition activity, while a value of “1” in both assays was considered as high inhibition activity.

Biocontrol efficacy assays in greenhouse and semi‐field conditions consisted of three independent biological replicates per treatment with five plants per replicate. Two independent experiments were performed in all three pathosystems in the greenhouse and semi‐field experiments except for the semi‐field and monitoring assays in Psa that were performed once. The biocontrol efficacy assay for Psa in the field consisted of four randomised blocks of five plants per treatment. Each block was repeated in separated rows. Disease incidence and Psa population levels were subjected to analysis of variance, and mean values were compared using the least significant difference test at p < .05. The analysis was performed with the General Linear Model (GLM) procedure of the Statistical Analysis System for Personal Computers (PC‐SAS) (Version 8.2; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

The monitoring of the LAB populations consisted of three independent biological replicates with five plants per replicate and two independent experiments.

The allelic profile of each L. plantarum strain obtained with MLST analysis was used to investigate clonal complexes (CCs) using the minimum spanning tree (MST) method (Bionumerics v7.5, Applied‐Maths, Sint‐Martens‐Latem, Belgium). Polymorphic DNA bands obtained with RAPD analysis were transformed into a binomial matrix (“1” for presence and “0” for absence of fragments). A dendrogram with the five series of RAPD‐PCR profiles of the 45 L. plantarum isolates was generated using the Dice coefficient of similarity and the UPGMA method (NTSYSpc).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Antagonistic activity against bacterial plant pathogens

Several LAB isolates severely inhibited growth (inhibition zone diameter > 10 mm) of Psa (NCPPB3739 and IVIA 3700‐1), Xap (CFBP3894 and CFBP5563) and Xf (IVIA XF349‐9A and CECT549). However, differences in sensitivity among Psa, Xap and Xf towards LAB were observed (see photographs Figure 1). The cluster analysis showed three main groups of antagonism spectrum at a similar level of 0.55 (Figure 1). Cluster 1 included 17 strains that generally showed no activity against Psa, moderate activity against Xap and moderate or high activity against Xf. Cluster 2 included 33 strains that generally showed no or moderate activity against Psa, and moderate or high activity against Xap and Xf. Interestingly, Cluster 3 included five strains—CC100, CM160, CM209, PM411 and TC92—that displayed broad and generally high activity against all the target pathogens.

Figure 1.

Dendrogram of the in vitro antagonism spectrum of 55 lactic acid bacteria (LAB) strains. The target pathogens are listed at the top and correspond to strains NCPPB3739 and IVIA 3700‐1 of Psa, strains CFBP3894 and CFBP5563 of Xap and strains CECT549 and IVIA XF349‐9A of XF. Two independent experiments were performed. Clusters of strains are indicated by a dot. Colour legend indicates the inhibition activity: Pale grey, negative in both experiments; dark grey, positive in one experiment; black, positive in both experiments. Cluster analysis was performed using the UPGMA and with the simple matching coefficient of similarity. The photographs A, B, and C show the antimicrobial activity obtained by the agar spot test in LBP, and the photographs D, E, F and G show the antimicrobial activity obtained by the disc test. IVIA, Instituto Valenciano de Investigaciones Agrarias; Psa: Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae; Xap, Xanthomonas arboricola pv. pruni; UPGMA, unweighted pair group method with the arithmetic average; XF, Xanthomonas fragariae

3.2. Psa, Xap and Xf control in plants under greenhouse conditions

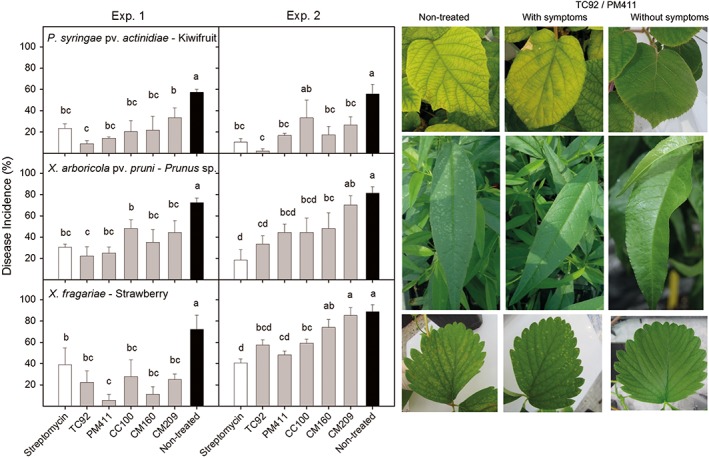

L. mesenteroides CM160 and CM209 and L. plantarum CC100, PM411 and TC92 were selected for efficacy assays in greenhouse conditions thanks to their broad and high in vitro antagonism against Psa, Xap and Xf. PM411 and TC92 strains consistently reduced Psa, Xap and Xf disease incidence in kiwifruit, Prunus and strawberry plants, respectively, in comparison with the non‐treated controls in both experiments performed (Figure 2). The efficacy of the L. plantarum strains in kiwifruit ranged from 84.5 to 96.3% for TC92 and from 70.0 to 75.4% for PM411, while in Prunus it ranged from 59.1 to 69.3% for TC92 and from 45.5 to 65.5% for PM411 and in strawberry from 35.4 to 69.2% for TC92 and from 45.8 to 92.3% for PM411. PM411 and TC92 did not differ significantly from streptomycin, except for PM411 in one experiment with the Xf‐strawberry pathosystem. CC100, CM160 and CM209, however, did not reduce disease incidence when compared to non‐treated plants in some experiments.

Figure 2.

Effect of the treatments with LAB strains (grey bars) on Psa, Xap and XF infections in kiwifruit, Prunus and strawberry plants, respectively, under greenhouse conditions. The effect of strains on disease incidence (%) was compared with streptomycin (white bars) and a non‐treated control (black bars). Two independent experiments were performed (left and right panels). Values are the mean of three replicates and error bars represent the SE of the mean. Bars with the same letter in the same panel do not differ significantly (p < 0.05) according to the LSD test. LSDPsa‐Exp.1 = 22.4; LSDPsa‐Exp.2 = 28.8; LSDXap‐Exp.1 = 23.4; LSDXap‐Exp.2 = 29.0; LSDXf‐Exp.1 = 32.8; LSDXf‐Exp.2 = 16.8. The photographs show the symptoms observed in non‐treated and treated plants. LAB, lactic acid bacteria; LSD, least significant difference; Psa, Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae; Xap, Xanthomonas arboricola pv. pruni; XF, Xanthomonas fragariae

3.3. Survival of L. plantarum PM411 and TC92 on leaves

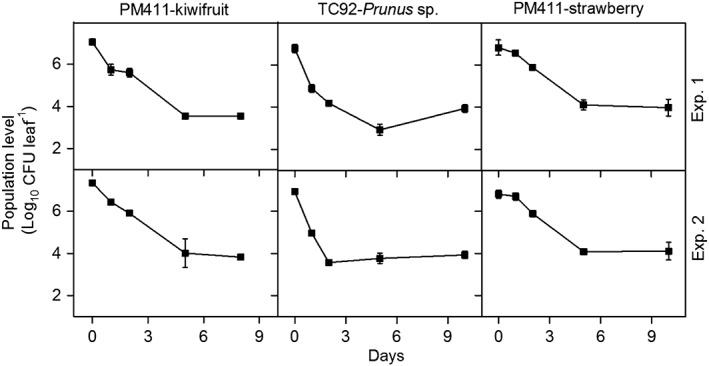

L. plantarum PM411 and TC92 survival on kiwifruit and strawberry plant leaves (PM411) and the leaves of Prunus plants (TC92) under greenhouse conditions was monitored (Figure 3). After inoculation, the population level decreased approximately two log units between the 1st and 10th day. In fact, the drop in population was observed during the first 5 days and the viable population remained stable thereafter at around 104 CFU per leaf.

Figure 3.

Survival of Lactobacillus plantarum PM411 in kiwifruit and strawberry plants and survival of L. plantarum TC92 in Prunus plants under controlled environmental conditions. Survival is shown as the population level (Log10 CFU leaf−1). Values are the mean of the three replicates, and error bars represent the SE of the mean. Two independent experiments were performed (top and bottom panels). CFU, colony‐forming units

3.4. Control of Psa, Xap and Xf in plants in semi‐field and field conditions

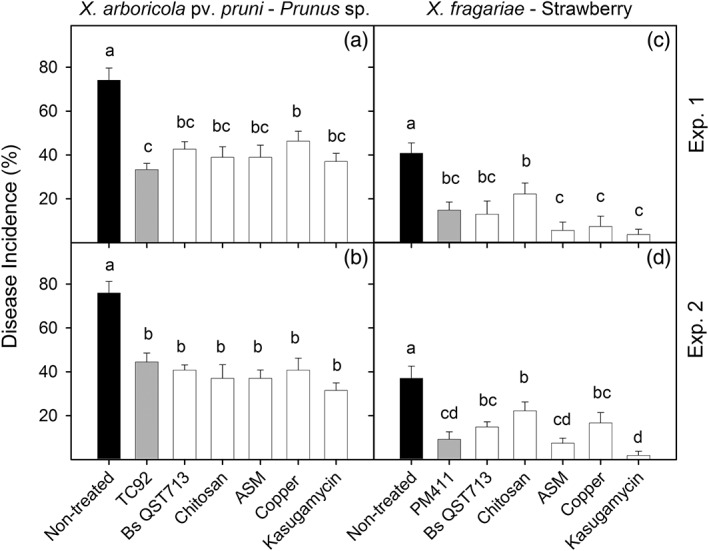

The efficacy of TC92 and PM411 in controlling Xap and Xf, respectively, was compared to reference products in semi‐field experiments (Figure 4). The incidence of infection attained in Prunus plants treated with L. plantarum TC92 was significantly lower than that of the non‐treated controls in both experiments performed. TC92 efficacy in controlling Xap on Prunus (41.5–55%) was not significantly different from B. subtilis QST713, chitosan, ASM and kasugamycin in either experiment or from copper in only one experiment. In both experiments, strawberry plants treated with L. plantarum PM411 showed a lower incidence of infection than the non‐treated controls did. PM411 efficacy (63.6–75%) in controlling Xf on strawberry did not differ significantly from B. subtilis QST713, ASM, copper and kasugamycin in either experiment or from chitosan in only one experiment.

Figure 4.

Effect of the treatment with Lactobacillus plantarum TC92 and PM411 (grey bars) on Xap infections in potted Prunus plants and on Xf infections in potted strawberry plants, respectively, in semi‐field experiments. The effect of strains on disease incidence (%) was compared with different reference products, such as B. subtilis QST713, chitosan, ASM, copper, and kasugamycin (white bars) and a non‐treated control (black bars). Two independent experiments were performed. Values are the mean of three replicates and error bars represent the SE of the mean. Bars with the same letter in the same panel do not differ significantly (p < 0.05) according to the LSD test. LSDXap‐Exp.1 = 12.7; LSDXap‐Exp.2 = 13.0; LSDXf‐Exp.1 = 12.8; LSDXf‐Exp.2 = 10.6. LSD, least significant difference; Xap, Xanthomonas arboricola pv. pruni; Xf, Xanthomonas fragariae

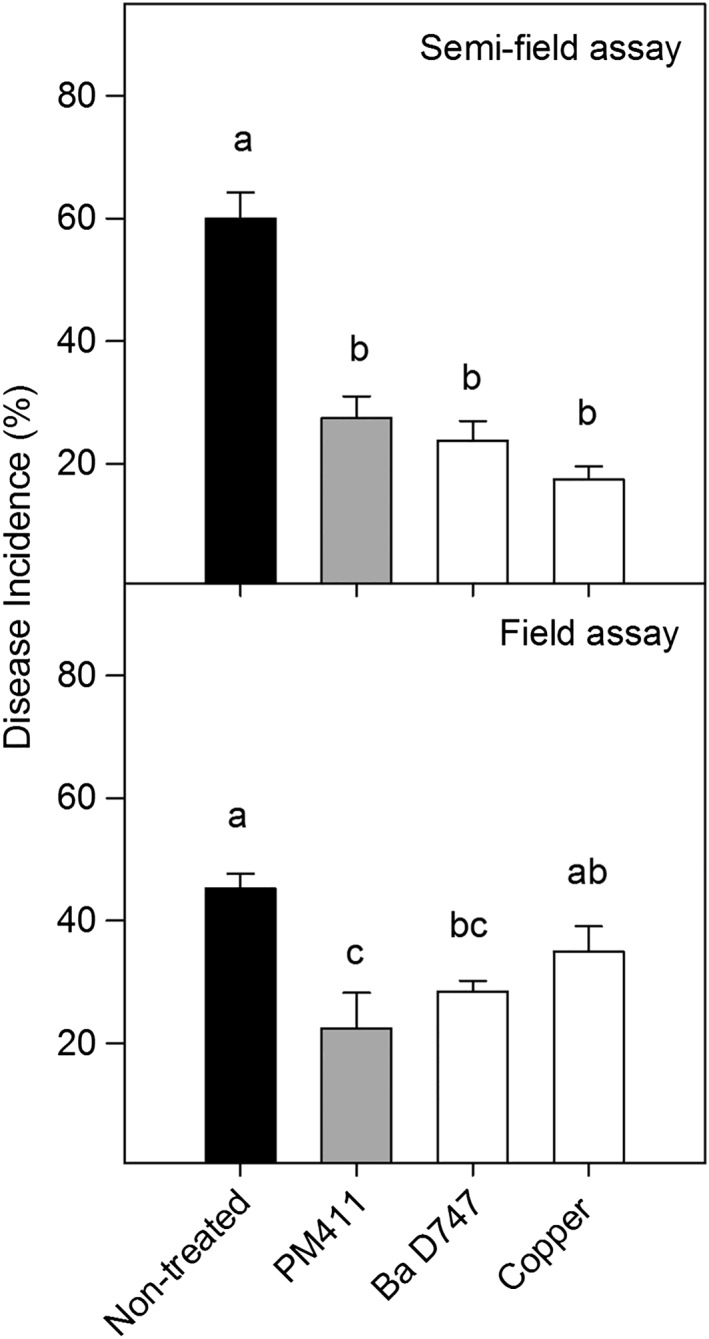

The efficacy of PM411 in controlling Psa was compared to reference products in a semi‐field experiment (Figure 5). PM411 was able to halve disease incidence in kiwifruit plants in comparison to non‐treated controls with significant differences. PM411 efficacy in controlling Psa on kiwifruit (54.2%) was similar to that of B. amyloliquefaciens D747 and copper without any significant differences between them.

Figure 5.

Effect of the treatment with Lactobacillus plantarum PM411 (grey bars) on Psa infections in kiwifruit plants in semi‐field and field experiments. The effect of PM411 on disease incidence (%) was compared with reference products such as B. amyloliquefaciens D747 and copper (white bars), and a non‐treated control (black bars). Values are the mean of three replicates and error bars represent the SE of the mean. Bars with the same letter in the same panel do not differ significantly (p < 0.05) according to the LSD test. LSDSemi‐field = 13.5; LSDField = 11.7. Ba, B. amyloliquefaciens; LSD, least significant difference; Psa, Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae

In the field experiment performed in a commercial kiwifruit orchard, the natural Psa incidence in non‐treated plants was 45.3%. PM411 was the most effective treatment in lowering the incidence of disease, reaching a 50.3% efficacy and no significant differences were observed in comparison with B. amyloliquefaciens D747 as a reference product, which showed a 22.7% efficacy (Figure 5). Copper did not significantly reduce disease incidence in comparison to non‐treated controls, showing a 37.1% efficacy.

3.5. Psa population suppression by PM411

The epiphytic and endophytic populations of Psa on the leaves of the potted kiwifruit plants treated with PM411 were monitored for 4 days post pathogen inoculation (dpi) in high RH conditions (Table 3). The Psa population recovered from the leaves of the plants treated with PM411 was lower than that of the untreated plants. Specifically, for the epiphytic population, the reduction (1 log unit) was significant at 1 dpi, while for the endophytic population it was observed as being 4 dpi. A reduction in the Psa population from 1.5 to 2 log units was observed in streptomycin‐treated plants.

Table 3.

Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum PM411 treatment on survival of Psa in kiwifruit plants

| Psa population levelsa | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epiphytic (Log10 CFU leaf−1) | Endophytic (Log10 CFU g−1) | |||||||

| Treatmentb | 1 day | 4 days | 1 day | 4 days | ||||

| PM411 | 6.1 | b | 5.5 | ab | 3.7 | A | 2.8 | b |

| Streptomycin | 5.4 | c | 5.0 | b | 2.7 | B | <2c | c |

| Non‐treated | 7.2 | a | 6.5 | a | 4.0 | A | 3.6 | a |

| LSD | 0.48 | 1.02 | 0.58 | 0.23 | ||||

CFU: colony‐forming units; LSD: least significant difference; Psa: Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae.

Values of Psa population levels are the mean of the three replicates one and 4 days post Psa inoculation on plants. Values with different letters in the same column are significantly different (p < 0.05) according to the LSD test.

Treatments were carried out 1 day before Psa inoculation.

Log10 CFU g−1 value under detection limit.

3.6. Metabolite and genotypic characterisation of PM411 and TC92

To understand the antibacterial activity of PM411 and TC92, CFS were analysed. While CFS without pH adjustment (pH 3.8) showed antibacterial activity against the three target pathogens (Psa, Xap and Xf), the inhibitory activity was completely lost after CFS pH neutralisation and enzymatic treatments (tripsin, α‐chymotrypsin, proteinase K and catalase) had no impact on the inhibitory effect (data not shown). A similar amount of a mixture of D‐ and L‐lactic acid obtained from both strains was quantified in CFS (75.75 ± 0.63 mM for PM411 and 74.86 ± 1.02 mM for TC92), with D‐lactic acid being the predominant optical isomer in the mixture.

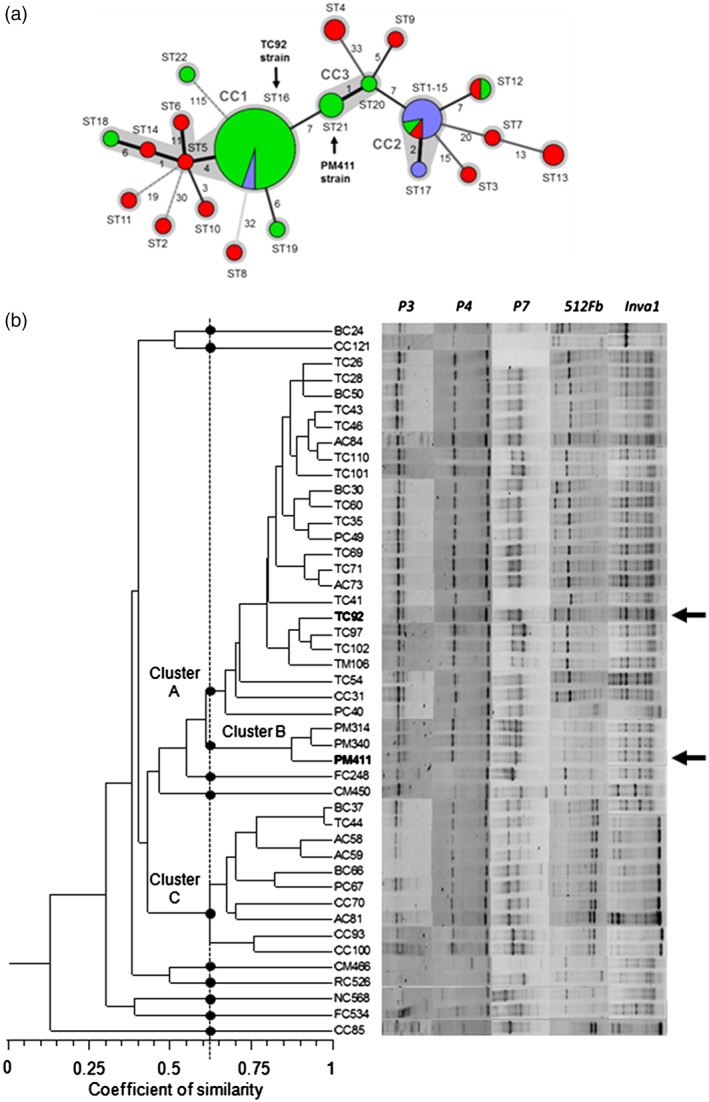

In relation to genotypic characterisation, the MST analysis of different L. plantarum strains based on MLST data (Figure S1, Supporting Information) is shown in Figure 6. Specifically, PM411 and TC92 were analysed together with other isolates of which 43 came from the INTEA‐CIDSAV culture collection and 26 from other studies. The six housekeeping genes yielded a total of 21 STs and the majority of the strains (66%) represented ST16 (n = 38) and ST1‐15 (n = 9). The 21 STs were grouped into three CCs. CC1 consisted of five STs that accounted for 42 strains, including ST5 as the putative primary founder. CC2 consisted of ST1‐15 represented by nine strains and ST17, which included one strain. CC3 was composed of ST20 and ST21 with four strains. The remaining STs were considered singletons. Specifically, PM411 and TC92 were found in two different CCs: TC92 in CC1 and PM411 in CC3. Strain PM411 shared ST21 with two strains from the INTEA‐CIDSAV collection. Strain TC92 shared ST16 with another 35 strains from the INTEA‐CIDSAV collection and with two strains studied by Tanganurat et al. (2009). The differences between TC92 and PM411 were found in purK1 and gdh.

Figure 6.

Minimum spanning tree of 71 Lactobacillus plantarum isolates based on allelic profiles of the genes pgm, ddl, gyrB, purK1, gdh and mutS (A). Each circle corresponds to an ST, and the size of the circle is proportional to the number of isolates within any given ST. Colour codes of isolates: Green, INTEA‐CIDSAV collection; red, de las Rivas et al. (2006); and blue, Tanganurat et al. (2009). The type of line between isolates indicates the strength of the genetic relationship between them (black, strong relationship; grey, intermediate relationship; and dotted line, weak relationship). The number of mutations between STs is also indicated for each relationship. STs that belong to the same CC are shown as circles grouped in a grey area. Black arrows indicate that the PM411 strain with ST21 belongs to CC3, and the TC92 strain with ST16 belongs to CC1. Dendrogram of the RAPD‐PCR patterns of 45 L. plantarum strains (INTEA‐CIDSAV collection) using primers P3, P4, P7, 512Fb and Inva1 (B). Dots indicate the three main clusters as well as the singletons. Cluster analysis was performed using the (UPGMA), and with the Dice coefficient of similarity. Black arrows indicate TC92 and PM411 strains. CC, clonal complex; INTEA‐CIDSAV, Institute of Food and Agricultural Technology and Center for Innovation and Development of Plant Health; RAPD‐PCR, randomly amplified polymorphic DNA‐PCR; ST, sequence type; UPGMA: unweighted pair group method with the arithmetic average

PM411 and TC92, together with 43 L. plantarum strains, were subjected to RAPD‐PCR analysis (Figure 6). According to the band profiles, the strains were divided into three clusters at a coefficient of similarity greater than 0.6. TC92 shared cluster A with 22 strains and PM411 shared cluster B with two other strains.

4. DISCUSSION

The growing interest in sustainable management of plant diseases caused by Psa, Xap and Xf has stimulated the search for novel BCA. While several bacteria, such as Pseudomonas and Xanthomonas, have been selected for studies thanks to their biocontrol activity against these pathogens, the studies in question only focused on a single pathogen (Biondi, Dallai, Brunelli, Bazzi, & Stefani, 2009; Henry, Gebben, Tech, Yip, & Leveau, 2016; Kawaguchi, Inoue, & Inoue, 2014; Wicaksono, Jones, Casonato, Monk, & Ridgway, 2018). In this present work, a multi‐disease approach was taken to select antagonistic bacteria with broad‐spectrum activity. This strategy has been previously used to screen for BCA in other pathosystems (Haidar et al., 2016). As some LAB strains have shown antagonistic activity against bacterial and fungal plant pathogens (Fhoula et al., 2013; Trias, Bañeras, Montesinos, & Badosa, 2008; Visser et al., 1986; Wang et al., 2011) and biocontrol efficacy on plants (Roselló et al., 2013; Roselló et al., 2017; Shrestha, Kim, & Park, 2014; Tsuda et al., 2016), plant‐associated LAB have been considered as candidates for developing BCA.

Five out of 55 LAB strains (CC100, CM160, CM209, PM411 and TC92) were selected as they exhibited a broad spectrum of in vitro antagonism against Psa, Xap and Xf. Other reports have also demonstrated the high antagonistic activity of certain LAB strains against phytopathogenic bacteria such as Xanthomonas campestris, Pectobacterium carotovorum, P. syringae, Pseudomonas savastanoi and Ralstonia solanacearum (Fhoula et al., 2013; Shrestha et al., 2014; Trias, Bañeras, Montesinos, & Badosa, 2008). in vitro assays are commonly used for the preliminary selection of antagonist strains from a huge number of candidates, testing different target phytopathogens (Kavroulakis et al., 2010; Mora, Cabrefiga, & Montesinos, 2015). This strategy is mainly focused on selecting antagonists, such as LAB (Ben Omar et al., 2008), whose mode of action is the secretion of antimicrobial compounds (Köhl et al., 2011). Therefore, this method allowed BCA candidate strains to be preselected.

In planta tests based on a multiple‐pathosystem approach were apt for highlighting strains with potential biocontrol ability and broad‐spectrum activity from among those previously selected in the in vitro tests. The biocontrol activity of PM411 and TC92 against Psa, Xap and Xf was confirmed in plants under greenhouse conditions, as pathogen infections were reduced in the same way as streptomycin. In a previous study, both strains were also selected in a screening procedure because they exhibited a suppressive effect against Erwinia amylovora in plant assays (Roselló et al., 2013).

The biocontrol efficacy of PM411 and TC92 against Psa, Xap and Xf in the corresponding host plants was also observed in the semi‐field and field experiments, confirming that they could be useful in a wide range of conditions. Because of the European Union (EU) regulatory quarantine restrictions for pathogens, the assessment of disease management strategies in orchards affected with these pathogens is practically unworkable in designated protected zones such as Spain. Therefore, semi‐field experiments have been performed in this study as they have been previously reported as being comparable to field experiments for biocontrol testing (Cabrefiga, Francés, Montesinos, & Bonaterra, 2011).

Biocontrol efficacy of the selected LAB strains was comparable to B. amyloliquefaciens D747, B. subtilis QST713, chitosan, ASM, copper and kasugamycin. Because of the restrictions on the use of commercial products, LAB strains could be a promising alternative tool to be included in disease management strategies. In particular, phytotoxicity and pathogen resistance selections, in terms of copper compounds and antibiotics used for Psa, Xap and Xf control, have been reported (Colombi et al., 2017; Lalancette & McFarland, 2007; Roberts, Jones, Chandler, & Stall, 1997). However, with some plant, defence elicitors such as ASM (Reglinski et al., 2013) and commercial microbial biopesticides based on Bacillus spp. against Psa (Monchiero, Gullino, Pugliese, Spadaro, & Garibaldi, 2015), a lack of consistency in efficacy has been demonstrated under some limited conditions.

Because of their potential as biological control agents, PM411 and TC92 were characterised in terms of the mechanism involved in the antimicrobial activity against the pathogens as well as genetically typified for their development as BCA. CFSs obtained from cultures of both strains also showed an inhibitory effect, indicating the presence of antimicrobial compounds. In fact, lactic acid production was confirmed in PM411 and TC92 cell cultures. Meanwhile, plantaricin synthesis by both strains is to be expected as a result of the presence of biosynthetic genes (plnEF, plnJK) with similar levels of expression (Daranas, Badosa, Francés, Montesinos, & Bonaterra, 2018; Roselló et al., 2013). As the pH neutralisation of CFS eliminated the antibacterial effect, acidic pH or the presence of organic acids could account for the main antimicrobial activity. Other studies have reported organic acids as being one of the main mechanisms through which the antimicrobial activity of LAB is exerted against a broad spectrum of target bacteria (Arena et al., 2016). Although in this work plantaricins have not been proven to contribute to Psa, Xap and Xf inhibition, their role should not be dismissed because acidification or acid‐mediated cell membrane disruption may be required to exert an antagonistic effect (Alakomi et al., 2000). Although the role hydrogen peroxide plays in antimicrobial activity was not confirmed in CFS, its production is expected to be favoured on plant surfaces where there are aerobic conditions, and to contribute to pathogen suppression as has been previously reported (Pridmore, Pittet, Praplan, & Cavadini, 2008). It is hypothesized that when L. plantarum colonise the plant surfaces the pH will be acidic because of the production of lactic acid or other organic acids resulting from fermentation. Moreover, under aerobic conditions, the formation of hydrogen peroxide could also contribute to the antagonism. Therefore, to fully understand the multifactorial mode of the actions of PM411 and TC92 responsible for disease prevention in plants, further studies are required.

Besides the production of antimicrobial metabolites, the pre‐emptive colonisation of plant tissues susceptible to pathogen infection is an important mechanism underlying BCA effectiveness (Giddens, Houliston, & Mahanty, 2003). As Psa, Xap and Xf enter the host plant through natural openings, such as leaf stomata or wounds, the presence of PM411 and TC92 cells on the leaf surfaces prior to the arrival of pathogens might avoid infection. In particular, preventively spraying PM411 on plants inhibited endophytic and epiphytic Psa populations, indicating a direct effect on the pathogen and in keeping with the reduction in the incidence of disease in the plant experiments. This inhibitory effect that PM411 and TC92 have, was also observed for E. amylovora on pear plant surfaces (Roselló et al., 2017). The survival of PM411 and TC92 on kiwifruit, Prunus and strawberry plant leaves was confirmed in greenhouse experiments. Similar population levels were reached on the three different plant hosts and were in agreement with their survival previously reported for pear plants (Roselló et al., 2017). Although after spraying a decrease in the population was observed as a result of the harsh conditions on aerial plant surfaces, a constant level of 103 to 104 CFU leaf−1 of LAB strains was attained in the 10 days that followed. This decline in population on leaves was also reported for other L. plantarum BCA which, interestingly, attained higher population levels at the wounded sites of leaves (Tsuda et al., 2016). Changes in water availability and temperature, nutrient limitation or ultraviolet radiation on leaves can be transiently inadequate for BCA growth (Lindow & Brandl, 2003).

Although the performance of PM411 and TC92 in supressing pathogens is similar and both strains were identified as L. plantarum, they were clearly discriminated by the RAPD‐PCR analysis and belong to different CCs according to the MLST. Interestingly, these strains were analysed together with other plant‐associated L. plantarum strains and both the RAPD‐PCR and the MLST analysis displayed similar groups.

L. plantarum PM411 and TC92 are effective as preventative treatments to control bacterial pathogens representing different genera (Pseudomonas, Xanthomonas) and affecting different hosts (kiwifruit, Prunus, strawberry). The broad‐spectrum antagonism against bacterial pathogens they exhibited is mainly based on antimicrobial metabolites. Moreover, they inhibited pathogen populations on plant surfaces by suppressing infections. However, population reduction by PM411 and TC92 under nonconductive conditions might compromise plant protection. To achieve the BCA population required for biocontrol, repeated spray applications may be necessary. Therefore, monitoring viable cells could aid the design of a suitable delivery schedule of applications (Daranas et al., 2018). Likewise, the improvement of BCA ecological fitness could be implemented (Daranas, Badosa, et al., 2018). Further studies under different agricultural and climatic conditions are needed to confirm the performance of PM411 and TC92 in the field.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Dendrogram according to the multilocus sequence typing (MLST) typing of 71 Lactobacillus plantarum strains, including 45 strains from this study (Roselló et al., 2013; Trias, Bañeras, Badosa, & Montesinos, 2008; Trias, Bañeras, Montesinos, & Badosa, 2008) and 26 strains from other studies. The analysis included allelic profiles of the genes pgm, ddl, gyrB, purK1, gdh and mutS. Colour codes of strains: green, this study; red, de las Rivas, Marcobal, and Muñoz (2006); and blue, Tanganurat, Quinquis, Leelawatcharamas, and Bolotin (2009). Cluster analysis was performed by MEGA version 5.1 software (http://www.megasoftware.net) using the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages (UPGMA) and the Kimura two‐parameter model (1,000 Bootstrap method). Bootstrap confidence intervals, origin of the isolates, sequence type (ST) and allelic profiles (in brackets) are indicated.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding was provided by AGL2015‐69876‐C2‐1‐R (Spain Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad and FEDER of the European Union), by FP7‐KBBE.2013.1.2‐04 613678 DROPSA of the European Union, and by the MPCUdG2016 grant (University of Girona). N. Daranas was recipient of the research grant 2015 FI_B00515 (Secretaria d'Universitats i Recerca, Departament d'Economia i Coneixement, Generalitat de Catalunya; ES, EU). The research group is accredited by SGR 2014‐697 and TECNIO net from the Department d'Economia i Coneixement‐ACCIÓ Catalonia.

Daranas N, Roselló G, Cabrefiga J, et al. Biological control of bacterial plant diseases with Lactobacillus plantarum strains selected for their broad‐spectrum activity. Ann Appl Biol. 2019;174:92–105. 10.1111/aab.12476

Funding information Universitat de Girona, Grant/Award Number: MPCUdG2016; Department d'Economia i Coneixement‐ACCIÓ Catalonia, Grant/Award Number: SGR 2014‐697; Secretaria d'Universitats i Recerca, Departament d'Economia i Coneixement, Generalitat de Catalunya, Grant/Award Number: 2015 FI_B00515; European Union FP7 Food, Agriculture and Fisheries, Biotechnology, Grant/Award Number: FP7‐KBBE.2013.1.2‐04 613678; Spain Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad and European Fund for Economic and Regional Development (FEDER) of the European Union, Grant/Award Number: AGL2015‐69876‐C2‐1‐R

REFERENCES

- Alakomi, H.‐L. , Skyttä, E. , Saarela, M. , Mattila‐Sandholm, T. , Latva‐Kala, K. , & Helander, I. M. (2000). Lactic acid permeabilizes Gram‐negative bacteria by disrupting the outer membrane. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 66, 2001–2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arena, M. P. , Silvain, A. , Normanno, G. , Grieco, F. , Drider, D. , Spano, G. , & Fiocco, D. (2016). Use of Lactobacillus plantarum strains as a bio‐control strategy against food‐borne pathogenic microorganisms. Frontiers in Microbiology, 7, 464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Omar, N. , Abriouel, H. , Keleke, S. , Sánchez Valenzuela, A. , Martínez‐Cañamero, M. , Lucas López, R. , … Gálvez, A. (2008). Bacteriocin‐producing Lactobacillus strains isolated from poto poto, a Congolese fermented maize product, and genetic fingerprinting of their plantaricin operons. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 127, 18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biondi, E. , Dallai, D. , Brunelli, A. , Bazzi, C. , & Stefani, E. (2009). Use of a bacterial antagonist for the biological control of bacterial leaf/fruit spot of stone fruits. IOBC/WPRS Bulletin, 43, 277–281. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, P. G. , & Hildebrand, P. D. (2013). Effect of sugar alcohols, antioxidants and activators of systemically acquired resistance on severity of bacterial angular leaf spot (Xanthomonas fragariae) of strawberry in controlled environment conditions. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology, 35, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrefiga, J. , Francés, J. , Montesinos, E. , & Bonaterra, A. (2011). Improvement of fitness and efficacy of a fire blight biocontrol agent via nutritional enhancement combined with osmoadaptation. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 77, 3174–3181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, A. , & Sarojini, V. (2014). Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae: Chemical control, resistance mechanisms and possible alternatives. Plant Pathology, 63, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Cellini, A. , Buriani, G. , Rocchi, L. , Eondelli, E. , Savioli, S. , Rodriguez Estrada, M. T. , … Spinelli, F. (2018). Biological relevance of volatile organic compounds emitted during the pathogenic interactions between apple plants and Erwinia amylovora . Molecular Plant Pathology, 19, 158–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cellini, A. , Fiorentini, L. , Buriani, G. , Yu, J. , Donati, I. , Cornish, D. A. , … Spinelli, F. (2014). Elicitors of the salicylic acid pathway reduce incidence of bacterial canker of kiwifruit caused by Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidae . Annals of Applied Biology, 165, 441–453. [Google Scholar]

- Chagnaud, P. , Machinis, K. , Coutte, L. A. , Marecat, A. , & Mercenier, A. (2001). Rapid PCR‐based procedure to identify lactic acid bacteria: Application to six common Lactobacillus species. Journal of Microbiological Methods, 44, 139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombi, E. , Straub, C. , Künzel, S. , Templeton, M. D. , McCann, H. C. , & Rainey, P. B. (2017). Evolution of copper resistance in the kiwifruit pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae through acquisition of integrative conjugative elements and plasmids. Environmental Microbiology, 19, 819–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, S. , Mahony, J. , & Van Sinderen, D. (2013). Broad‐spectrum antifungal‐producing lactic acid bacteria and their application in fruit models. Folia Microbiologica, 58, 291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daranas, N. , Badosa, E. , Francés, J. , Montesinos, E. , & Bonaterra, A. (2018). Enhancing water stress tolerance improves fitness in biological control strains of Lactobacillus plantarum in plant environments. PLoS One, 13, e0190931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daranas, N. , Bonaterra, A. , Francés, J. , Cabrefiga, J. , Montesinos, E. , & Badosa, E. (2018). Monitoring viable cells of the biological control agent Lactobacillus plantarum PM411 in aerial plant surfaces by means of a strain‐specific viability quantitative PCR method. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 84, e00107–e00118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de las Rivas, B. , Marcobal, A. , & Muñoz, R. (2006). Development of a multilocus sequence typing method for analysis of Lactobacillus plantarum strains. Microbiology, 152, 85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cagno, R. , Minervini, G. , Sgarbi, E. , Lazzi, C. , Bernini, V. , Neviani, E. , & Gobbetti, M. (2010). Comparison of phenotypic (biolog system) and genotypic (random amplified polymorphic DNA‐polymerase chain reaction, RAPD‐PCR, and amplified fragment length polymorphism, AFLP) methods for typing Lactobacillus plantarum isolates from raw vegetables and fruits. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 143, 246–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donati, I. , Buriani, G. , Cellini, A. , Mauri, S. , Costa, G. , & Spinelli, F. (2014). New insights on the bacterial canker of kiwifruit (Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae). Journal of Berry Research, 4, 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Fhoula, I. , Najjari, A. , Turki, Y. , Jaballah, S. , Boudabous, A. , & Ouzari, H. (2013). Diversity and antimicrobial properties of lactic acid bacteria isolated from rhizosphere of olive trees and desert truffles of Tunisia. BioMed Research International, 2013, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallelli, A. , Talocci, S. , L'Aurora, A. , & Loreti, S. (2011). Detection of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae, causal agent of bacterial canker of kiwifruit, from symptomless fruits and twigs, and from pollen. Phytopathologia Mediterranea, 50, 462–472. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, S. R. , Houliston, G. J. , & Mahanty, H. K. (2003). The influence of antibiotic production and pre‐emptive colonization on the population dynamics of Pantoea agglomerans (Erwinia herbicola) Eh1087 and Erwinia amylovora in planta. Environmental Microbiology, 5, 1016–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidar, R. , Deschamps, A. , Roudet, J. , Calvo‐Garrido, C. , Bruez, E. , Rey, P. , & Fermaud, M. (2016). Multi‐organ screening of efficient bacterial control agents against two major pathogens of grapevine. Biological Control, 92, 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hazel, W. , & Civerolo, E. (1980). Procedures for growth and inoculation of Xanthomonas fragariae, causal organism of angular leaf spot of strawberry. Plant Disease, 64, 178–181. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, P. M. , Gebben, S. J. , Tech, J. J. , Yip, J. L. , & Leveau, J. H. J. (2016). Inhibition of Xanthomonas fragariae, causative agent of angular leaf spot of strawberry, through iron deprivation. Frontiers in Microbiology, 7, 1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt, S. M. , & Cote, G. L. (1998). Differentiation of dextran‐producing Leuconostoc strains by a modified randomly amplified polymorphic DNA protocol. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 64, 3096–3098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavroulakis, N. , Ntougias, S. , Besi, M. I. , Katsou, P. , Damaskinou, A. , Ehaliotis, C. , … Papadopoulou, K. K. (2010). Antagonistic bacteria of composted agro‐industrial residues exhibit antibiosis against soil‐borne fungal plant pathogens and protection of tomato plants from Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. radicis‐lycopersici . Plant and Soil, 333, 233–247. [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi, A. , Inoue, K. , & Inoue, Y. (2014). Biological control of bacterial spot on peach by nonpathogenic Xanthomonas campestris strains AZ98101 and AZ98106. Journal of General Plant Pathology, 80, 158–163. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.‐R. , Gang, G.‐H. , Jeon, C.‐W. , Kang, N. J. , Lee, S.‐W. , & Kwak, Y.‐S. (2016). Epidemiology and control of strawberry bacterial angular leaf spot disease caused by Xanthomonas fragariae . The Plant Pathology Journal, 32, 290–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhl, J. , Postma, J. , Nicot, P. , Ruocco, M. , & Blum, B. (2011). Stepwise screening of microorganisms for commercial use in biological control of plant‐pathogenic fungi and bacteria. Biological Control, 57, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lalancette, N. , & McFarland, K. A. (2007). Phytotoxicity of copper‐based bactericides to peach and nectarine. Plant Disease, 91, 1122–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamichhane, J. R. (2014). Xanthomonas arboricola diseases of stone fruit, almond, and walnut trees: Progress toward understanding and management. Plant Disease, 98, 1600–1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamichhane, J. R. , Arendse, W. , Dachbrodt‐Saaydeh, S. , Kudsk, P. , Roman, J. C. , van Bijsterveldt‐Gels, J. E. , … Messéan, A. (2015). Challenges and opportunities for integrated pest management in Europe: A telling example of minor uses. Crop Protection, 74, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lindow, S. E. , & Brandl, M. T. (2003). Microbiology of the phyllosphere. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 69, 1875–1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llop, P. , Caruso, P. , Cubero, J. , Morente, C. , & López, M. M. (1999). A simple extraction procedure for efficient routine detection of pathogenic bacteria in plant material by polymerase chain reaction. Journal of Microbiological Methods, 37, 23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López, I. , Torres, C. , & Ruiz‐Larrea, F. (2008). Genetic typification by pulsed‐field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) of wild Lactobacillus plantarum and Oenococcus oeni wine strains. European Food Research and Technology, 227, 547–555. [Google Scholar]

- Matyjaszczyk, E. (2015). Products containing microorganisms as a tool in integrated pest management and the rules of their market placement in the European Union. Pest Management Science, 71, 1201–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus, P. S. , Stockwell, V. O. , Sundin, G. W. , & Jones, A. L. (2002). Antibiotic use in plant agriculture. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 40, 443–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monchiero, M. , Gullino, M. L. , Pugliese, M. , Spadaro, D. , & Garibaldi, A. (2015). Efficacy of different chemical and biological products in the control of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae on kiwifruit. Australasian Plant Pathology, 44, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Montesinos, E. , & Bonaterra, A. (2017). Pesticides, microbial In Reference module in life sciences. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier; 10.1016/B978-0-12-809633-8.13087-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mora, I. , Cabrefiga, J. , & Montesinos, E. (2015). Cyclic lipopeptide biosynthetic genes and products, and inhibitory activity of plant‐associated Bacillus against phytopathogenic bacteria. PLoS One, 10, e0127738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pridmore, R. D. , Pittet, A.‐C. , Praplan, F. , & Cavadini, C. (2008). Hydrogen peroxide production by Lactobacillus johnsonii NCC 533 and its role in anti‐Salmonella activity. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 283, 210–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahn, K. , De Grandis, S. A. , Clarke, R. C. , McEwen, S. A. , Galán, J. E. , Ginocchio, C. , … Gyles, C. L. (1992). Amplification of an invA gene sequence of Salmonella typhimurium by polymerase chain reaction as a specific method of detection of Salmonella . Molecular and Cellular Probes, 6, 271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reglinski, T. , Vanneste, J. L. , Wurms, K. , Gould, E. , Spinelli, F. , & Rikkerink, E. (2013). Using fundamental knowledge of induced resistance to develop control strategies for bacterial canker of kiwifruit caused by Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae . Frontiers in Plant Science, 4, 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis, J. A. , Paula, A. T. , Casarotti, S. N. , & Penna, A. L. B. (2012). Lactic acid bacteria antimicrobial compounds: Characteristics and applications. Food Engineering Reviews, 4, 124–140. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, P. D. , Jones, J. B. , Chandler, C. K. , & Stall, R. E. (1997). Disease progress, yield loss, and control of Xanthomonas fragariae on strawberry plants. Plant Disease, 81, 917–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselló, G. , Bonaterra, A. , Francés, J. , Montesinos, L. , Badosa, E. , & Montesinos, E. (2013). Biological control of fire blight of apple and pear with antagonistic Lactobacillus plantarum . European Journal of Plant Pathology, 137, 621–633. [Google Scholar]

- Roselló, G. , Francés, J. , Daranas, N. , Montesinos, E. , & Bonaterra, A. (2017). Control of fire blight of pear trees with mixed inocula of two Lactobacillus plantarum strains and lactic acid. Journal of Plant Pathology, 99 (Special issue), 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, A. , Kim, B. S. , & Park, D. H. (2014). Biological control of bacterial spot disease and plant growth‐promoting effects of lactic acid bacteria on pepper. Biocontrol Science and Technology, 24, 763–779. [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli, F. , Donati, I. , Vanneste, J. L. , Costa, M. , & Costa, G. (2011). Real time monitoring of the interactions between Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae and Actinidia species. Acta Horticulturae, 913, 461–465. [Google Scholar]

- Sundin, G. W. , Werner, N. A. , Yoder, K. S. , & Aldwinckle, H. S. (2009). Field evaluation of biological control of fire blight in the eastern United States. Plant Disease, 93, 386–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tailliez, P. , Tremblay, J. , Ehrlich, S. D. , & Chopin, A. (1998). Molecular diversity and relationship within Lactococcus lactis, as revealed by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD). Systematic and Applied Microbiology, 21, 530–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanganurat, W. , Quinquis, B. , Leelawatcharamas, V. , & Bolotin, A. (2009). Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of Lactobacillus plantarum strains isolated from Thai fermented fruits and vegetables. Journal of Basic Microbiology, 49, 377–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torriani, S. , Felis, G. E. , & Dellaglio, F. (2001). Differentiation of Lactobacillus plantarum, L. pentosus, and L. paraplantarum by recA gene sequence analysis and multiplex PCR assay with recA gene‐derived primers. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 67, 3450–3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trias, R. , Bañeras, L. , Badosa, E. , & Montesinos, E. (2008). Bioprotection of Golden Delicious apples and Iceberg lettuce against foodborne bacterial pathogens by lactic acid bacteria. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 123, 50–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trias, R. , Bañeras, L. , Montesinos, E. , & Badosa, E. (2008). Lactic acid bacteria from fresh fruit and vegetables as biocontrol agents of phytopathogenic bacteria and fungi. International Microbiology, 11, 231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda, K. , Tsuji, G. , Higashiyama, M. , Ogiyama, H. , Umemura, K. , Mitomi, M. , … Kosaka, Y. (2016). Biological control of bacterial soft rot in Chinese cabbage by Lactobacillus plantarum strain BY under field conditions. Biological Control, 100, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, R. , Holzapfel, W. H. , Bezuidenhout, J. J. , & Kotze, J. M. (1986). Antagonism of lactic acid bacteria against phytopathogenic bacteria. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 52, 552–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. , Yan, H. , Shin, J. , Huang, L. , Zhang, H. , & Qi, W. (2011). Activity against plant pathogenic fungi of Lactobacillus plantarum IMAU10014 isolated from Xinjiang koumiss in China. Annals of Microbiology, 61, 879–885. [Google Scholar]

- Wicaksono, W. A. , Jones, E. E. , Casonato, S. , Monk, J. , & Ridgway, H. J. (2018). Biological control of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae (Psa), the causal agent of bacterial canker of kiwifruit, using endophytic bacteria recovered from a medicinal plant. Biological Control, 116, 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Yáñez‐López, R. , Torres‐Pacheco, I. , Guevara‐González, R. G. , Hernández‐Zul, M. I. , Quijano‐Carranza, J. A. , & Rico‐García, E. (2012). The effect of climate change on plant diseases. African Journal of Biotechnology, 11, 2417–2428. [Google Scholar]

- Zwielehner, J. , Handschur, M. , Michaelsen, A. , Irez, S. , Demel, M. , Denner, E. B. M. , & Haslberger, A. G. (2008). DGGE and real‐time PCR analysis of lactic acid bacteria in bacterial communities of the phyllosphere of lettuce. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research, 52, 614–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Dendrogram according to the multilocus sequence typing (MLST) typing of 71 Lactobacillus plantarum strains, including 45 strains from this study (Roselló et al., 2013; Trias, Bañeras, Badosa, & Montesinos, 2008; Trias, Bañeras, Montesinos, & Badosa, 2008) and 26 strains from other studies. The analysis included allelic profiles of the genes pgm, ddl, gyrB, purK1, gdh and mutS. Colour codes of strains: green, this study; red, de las Rivas, Marcobal, and Muñoz (2006); and blue, Tanganurat, Quinquis, Leelawatcharamas, and Bolotin (2009). Cluster analysis was performed by MEGA version 5.1 software (http://www.megasoftware.net) using the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages (UPGMA) and the Kimura two‐parameter model (1,000 Bootstrap method). Bootstrap confidence intervals, origin of the isolates, sequence type (ST) and allelic profiles (in brackets) are indicated.