Abstract

Enamel renal syndrome is a unique syndrome associated with kidney agenesis associated with kidney agenesis, amelogenesis imperfecta, and gingival hyperplasia. The prevalence rate of this rare syndrome is <1/1,000,000. A 17-year-old male patient came to the department of periodontics, with a chief complaint of dislodged crown in the anterior teeth region. On clinical examination, the patient had teeth with mottled enamel and gingival enlargement. The orthopantomograph and gingival biopsy revealed pulpal calcification and gingival calcification, respectively. Furthermore, the renal ultrasonography revealed absence/agenesis of the left kidney. Thus, based on radiographical, histological, and ultrasound investigations, the patient was diagnosed with nephrocalcinosis syndrome. The patient was treated with periodontal therapy and prosthodontic full-mouth rehabilitation. This case report highlights the need of a periodontist to be acquainted about the signs and symptoms of the syndrome to benefit an individual in the right diagnosis and treatment plan.

Keywords: Amelogenesis imperfecta, gingival enlargement, nephrocalcinosis syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Enamel renal syndrome is a disorder characterized by autosomal recessive pattern featuring severe enamel hypoplasia, intrapulpal calcification, failed tooth eruption, and nephrocalcinosis. It is an extremely rare disorder. It is known by various syndromes such as amelogenesis imperfecta (AI) syndrome, MacGibbon syndrome, and Lubinsky-MacGibbon syndrome. It affects <1 in 100,000 people in the world population. It has been found out that the reason behind this syndrome is the FAM20A gene mutation.[1] Ever since the first report documented by MacGibbon in 1972, there have been only 10 other cases documented.[2,3]

The present case report describes a patient showing the typical features of AI, gingival hyperplasia, and nephron calcifications. In recent findings, genetic predisposition to nephrocalcinosis was found; however, the specific genetic and epigenetic factors are still not clear.

Various correlations have been observed showing gene polymorphism related to stone formation for calcium-sensing receptors and Vitamin D receptors. Repeated calcium stones associated with medullary sponge kidney may be related to an autosomal dominant mutation of a still unknown gene.[4]

In conjunction with the gene research, is another theory of how the disease manifests. This is called the free particle theory. This theory says that the primary core of lithogenic solutes along the segment of the nephrons leads to the formation, growth, and agglomeration of crystals that might get trapped in the tubular lumen and begin the outgrowth of stone formation. Some of the evidence behind this theory is the spurt of growth and crystals, diameter of segments of nephron, and transit time in the nephron. All of these combined showed more and more support for this theory.[5,6,7]

The purpose of the present case report is to describe a patient showing the typical feature of AI, gingival hyperplasia, and nephrocalcification/kidney agenesis and to highlight the important role of the dentist and periodontist in recognizing this unique syndrome.

CASE REPORT

A 17-year-old male child reported to the department of periodontics with the chief complaint of dislodged crown for a week duration. There was no history of any drug intake/allergies or systemic disease. The extraoral examination was unremarkable. On intraoral examination, there was bilateral missing canine and all the permanent teeth had a distinct yellow with an irregular and flaky hard surface. General attrition was observed which resulted in reduced vertical dimensions during occlusion. On soft tissue examination, the patient had pink and fibrotic gingiva in respect to maxillary arch and erythematous, soft, and boggy gingiva in respect to mandibular arch. The gingivae of both the arches bled on probing suggestive of generalized moderate inflammatory gingival enlargement as contemplated in Figure 1. The patient confirmed that his parents and a healthy sibling were systemically healthy and did not show any similar clinical abnormalities.

Figure 1.

Preoperative view

Orthopantomograph examination revealed enamel hypoplasia of all the teeth. The canine on either side of the maxillary quadrant were impacted. Pulpal calcifications were also seen in most of the teeth as observed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Orthopantomograph view

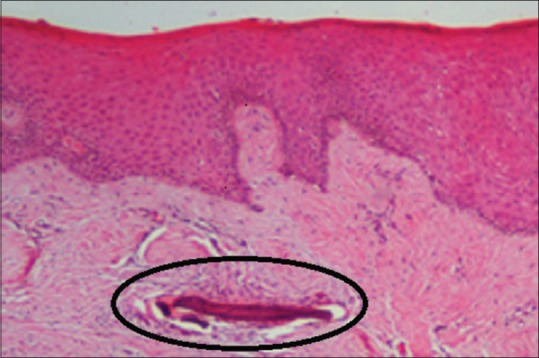

The hyperplastic gingival tissue was sent for histopathological examination which showed hyperplastic parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium. The underlying connective tissue was dense, fibrous showing thick collagen bundles with a focus of chronic inflammation consisting predominantly of plasma cells. Dystrophic gingival calcification was also seen in one area of the specimen as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Histopathological slide of gingival biopsy showing an encircled dystrophic gingival calcification

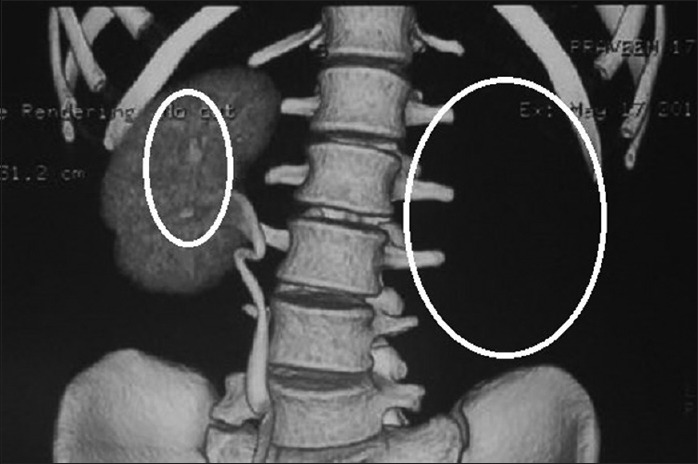

On further investigation, a renal ultrasound showed that agenesis of the left kidney and slight calcification in the right kidney were observed as seen in Figure 4. Laboratory findings including serum electrolytes, calcium, phosphate, urea, creatinine, alkaline phosphatase, and parathormone levels were all normal. The vital signs including blood pressure and respiratory rate were within normal range.

Figure 4.

Computed tomography showing agenesis of the left kidney and slight calcification in the right kidney (encircled)

Case management and clinical outcome

Initial treatment began with oral hygiene instructions followed by thorough supragingival and subgingival scaling and curettage. Plaque control reduced the gingival enlargement to an extent. Since a full-mouth rehabilitation with crowns was planned, periodontal flap with bone contouring (crown lengthening) was done for all the teeth in a quadrant-wise approach as viewed in Figure 5. After complete healing of the periodontal tissues, the all-ceramic crowns for the anterior teeth and metal crown for the posterior teeth were given as contemplated in Figure 6. The patient remains under regular dental and medical follow-up till date as observed in Figure 7.

Figure 5.

Periodontal flap surgery

Figure 6.

Postoperative healing and crown preparation

Figure 7.

Full-mouth crown rehabilitation after 1 month

DISCUSSION

AI represents a group of developmental conditions, along with a genomic influence affecting the structure and clinical appearance of enamel of all or nearly all the teeth in a more or less regular manner. The prevalence varies from 1:700 to 1:14,000 according to the population studies.[3] On the basis of clinical criteria, AI has been subdivided into hypoplastic or hypocalcified varieties. AI is also shown to be familial and can be inherited as autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, or X-linked dominant and X-linked recessive.[8]

The parents of this patient and his brother or any relatives had shown no similar condition, and thus, his parents could be accepted as heterozygous carriers of recessive gene or a new mutation may be an alternative explanation.

Generalized gingival enlargement may be due to a variety of causes including leukemia, genetics, nutrition, systemic conditions, and consumption of certain drugs, being some of them. These conditions were ruled out during the case history recording. The main reason of the enlargement was seen to be plaque induced and since the enlargement drastically reduced with scaling and thus, a diagnosis of plaque-induced gingival enlargement was confirmed.

Another important finding, in this case, was the presence of gingival, pulpal, and renal calcifications (nephrocalcinosis). Ectopic calcification has been reported in patients with disorders of calcium and phosphorus metabolism. However, in this patient, the serum levels of calcium and phosphorous metabolism were within normal limits. These findings were not in accordance to the cases presented by MacGibbon,[2] Lubinsky M,[3] Hall et al.,[9] and Hunter et al.,[10] where all the cases had impaired renal considerations and abnormalities in calcium and phosphorus metabolism, and hence, nephrocalcinosis may be a risk factor for renal impairment.[11]

Kantaputra et al. in 2014 examined a case having localized aggressive periodontitis, gingival fibromatosis, AI, nephrocalcinosis, and soft tissue calcification. Hence, they coined the term enamel–renal–gingival syndrome.[12] Similar features were seen in the case report described in this article with the patient having AI, generalized plaque-induced gingival enlargement, pulpal and gingival calcification, and nephrocalcinosis.

This is a rare autosomal disorder that has been proven to be associated with mutation in FAM20A gene. However, the mutation test was not possible in the present study due to financial constraints.

CONCLUSION

Concluding we have described a patient with AI, nephrocalcinosis syndrome with plaque-induced gingival enlargement (enamel–renal–gingival syndrome). The patient had normal renal function, and he was oblivious that he had this syndrome. Hence, if a patient having AI since young age with generalized gingival enlargement, the dentists who are often the first to notice these oral symptoms should consider referring the patient for renal examination to exclude the presence of the rare disorder.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.de la Dure-Molla M, Quentric M, Yamaguti PM, Acevedo AC, Mighell AJ, Vikkula M, et al. Pathognomonic oral profile of enamel renal syndrome (ERS) caused by recessive FAM20A mutations. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:84. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-9-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacGibbon D. Generalized enamel hypoplasia and renal dysfunction. Aust Dent J. 1972;17:61–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1972.tb02747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martelli-Júnior H, dos Santos Neto PE, de Aquino SN, de Oliveira Santos CC, Borges SP, Oliveira EA, et al. Amelogenesis imperfecta and nephrocalcinosis syndrome: A case report and review of the literature. Nephron Physiol. 2011;118:62–5. doi: 10.1159/000322828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lubinsky M, Angle C, Marsh PW, Witkop CJ., Jr Syndrome of amelogenesis imperfecta, nephrocalcinosis, impaired renal concentration, and possible abnormality of calcium metabolism. Am J Med Genet. 1985;20:233–43. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320200205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dellow EL, Harley KE, Unwin RJ, Wrong O, Winter GB, Parkins BJ, et al. Amelogenesis imperfecta, nephrocalcinosis, and hypocalciuria syndrome in two siblings from a large family with consanguineous parents. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:3193–6. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.12.3193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elizabeth J, Lakshmi Priya E, Umadevi KM, Ranganathan K. Amelogenesis imperfecta with renal disease – A report of two cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:625–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butler WT, Brunn JC, Qin C. Dentin extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins: Comparison to bone ECM and contribution to dynamics of dentinogenesis. Connect Tissue Res. 2003;44(Suppl 1):171–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crawford PJ, Aldred M, Bloch-Zupan A. Amelogenesis imperfecta. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:17. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall RK, Phakey P, Palamara J, McCredie DA. Amelogenesis imperfecta and nephrocalcinosis syndrome. Case studies of clinical features and ultrastructure of tooth enamel in two siblings. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;79:583–92. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(05)80100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunter L, Addy LD, Knox J, Drage N. Is amelogenesis imperfecta an indication for renal examination? Int J Paediatr Dent. 2007;17:62–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2006.00782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirzioglu Z, Ulu KG, Sezer MT, Yüksel S. The relationship of amelogenesis imperfecta and nephrocalcinosis syndrome. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;14:e579–82. doi: 10.4317/medoral.14.e579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kantaputra PN, Kaewgahya M, Khemaleelakul U, Dejkhamron P, Sutthimethakorn S, Thongboonkerd V, et al. Enamel-renal-gingival syndrome and FAM20A mutations. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164:1–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]