Abstract

Background:

Dentine hypersensitivity (DH) is a relatively common problem which may affect the adult population. The etiology remains multi-factorial with interactions between stimulus and pre-disposing factors causing its aggravation.

Aim:

To study the prevalence of DH and associated factors and also to find the association between various factors and DH.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional study was carried out and a total of 5091 patients, both male and females, were evaluated through questionnaire. Out of the total only 1400 patients were included in the study and were further evaluated clinically. A complete demographic data was obtained and the DH was confirmed by the use of air -water jet of the dental chair and scratching the suspected tooth with a dental probe. The pain response of the subject was recorded using the visual analog scale (VAS) and verbal rating scale (VRS). The data obtained was statistically evaluated and Chi-square test was applied for comparison of different demographic factors with DH.

Results:

The overall prevalence of DH was 27.4%. Various demographic factors were found to affect DH such as age, gender, education, and diet. The most common stimulus was found to be cold (21.4%) and common predisposing factor was gingival recession and attrition (28.6%). Clinical examination yielded a statistically significant association between VAS and VRS scores for DH and demographic factors.

Conclusion:

The prevalence of DH in present study was 27.4% which is attributed to gingival recession as predisposing factor and cold stimuli as the precipitating factor.

Keywords: Abrasion, dentin hypersensitivity, oral pain, recession, tooth wear

INTRODUCTION

DH is a relatively common problem faced by almost every individual and is also referred to as the common cold of dentistry. It can be defined as a short, sharp pain that arises from exposed dentin in response to stimuli (typically thermal, evaporative, tactile, osmotic or chemical) and that cannot be ascribed to any other form of dental defect or pathology.[1] The etiology remains multi-factorial, with interactions between stimulus and pre-disposing factors causing its aggravation. Many theories explain the outbreak of the painful response but, Hydrodynamic theory is the most accepted amongst them. It states that the peripheral stimuli are transmitted to the pulp surface through fluid movement inside the dentin ducts, causing pain.[2]

DH affects a significantly large proportion of the adult population and several studies have reported its prevalence among adult population to be ranging from 2.8% to 74%.[3,4,5] In India, the prevalence varies from place to place depending upon the local oral practices.[6] Few studies in Punjab, Chandigarh, Andhra Pradesh etc., stated that the prevalence of DH to be 25%, 47.8% and, 32%, respectively.[6,7,8] However, there is no available data on the prevalence of DH in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). Therefore, the aim of this study was to find the prevalence of DH, and also to find the association between various factors and DH in district Jammu of J&K.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A cross-sectional study was carried out in the Department of Periodontology, over a period of 6 months from September 2017 to March 2018. A total of 5091 patients, both male and females, were examined during the period. Out of the total patients examined, 1400 patients were included in the study.

The study was conducted in accordance with Helsinki declaration[9] approved by the Institutional ethics committee. An informed consent from the patient was also obtained prior to it.

Inclusion criteria

The patients between the age of 20 and 69 years, and with at least 20 functional teeth were included in the study. The patients who were not willing to sign the consent, medically compromised/pregnant/lactating mother(s), extensive carious and/restored tooth, tooth with prosthesis, fractured tooth were not included in the study.

Study design

A cross-sectional study was conducted to find the prevalence of DH and associated factors, and also to find the association between various factors and DH. The study was divided into two parts, i.e., Questionnaire and clinical examination.

The questionnaire was read to the subjects and answers were recorded by the examiner. The subjects who reported of hypersensitivity were clinically examined and were further diagnosed by the same examiner.

Questionnaire and clinical examination

The questionnaire (contact the corresponding author) included the detailed demographic data of the subject i.e., age, sex, location, education qualification, type of diet, provoking factors/stimulus, sensitivity episodes etc., The information was written down on the questionnaire by the examiner. Out of the 5091 subjects, 1400 subjects reported having hypersensitivity symptoms and were further assessed clinically.

The clinical examination was also performed by the same examiner after seating the subject on the dental chair. An air-water jet was used to blast air and water at the subjects tooth for 3 s at a distance of 1cms from the tooth surface (buccal, lingual and occlusal) and also the suspected tooth/teeth were scratched with a dental probe. The pain response of the subject was recorded using the visual analog scale (VAS) and verbal rating scale (VRS). A VAS consists of a 10cm line with anchors designed as 0, no pain; 2, mild pain; 4, moderate pain; 6, severe pain and; 10, worst pain.[10] The subjects had to mark on the scale at a point that corresponded to his/her reaction. The VRS consists of scores from 0 to 3 indicating the pain reaction, where 0 indicate no discomfort, 1 indicate mild discomfort, 2 indicate marked discomfort and, 3 indicate marked discomfort that lasts for more than 10 s.[11]

All the subjects were also examined for the tooth surface loss, such as attrition, erosion, gingival recession, abrasion or any of the combinations.

Statistical analysis

The data obtained was tabulated and put to statistical analysis using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM, USA). The categorical variables were presented as number and percentages. Chi-square test was applied for comparison of different demographic factors with DH and, a P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A cross-sectional study was conducted to find the prevalence of DH and associated factors, and also to find the association between various demographic factors and DH in which 1400 subjects suffering from DH were included in the study and evaluated.

The overall results in Table 1 demonstrated that out of 1400 patients of DH, the majority of the participants were in the age group 20–29 years (35.7%), followed by 50–59 years (28.6%) then 30–39 years (21.4%) and, 60–69 years and 40–49 years showing the least participants with only 7.1%. On comparison between gender, males demonstrated a higher percentage than females with 57.1% and 42.9%, respectively. The distribution of participants according to education level showed a high percentage of undergraduates (71.4%) and illiterates showed 14.3%, whereas graduates and post graduates share equal percentages of 7.1% each. The participants showed no variation in distribution according to location i.e. rural and urban. However, non-vegetarians (71.4) showed a higher number of DH cases than vegetarians (28.6%).

Table 1.

Distribution of participants according to demographic factors such as; age, gender, education, location and diet

The overall results in Table 1 demonstrated that out of 1400 patients of DH, the majority of the participants were in the age group 20–29 years (35.7%), followed by 50–59 years (28.6%) then 30–39 years (21.4%) and, 60–69 years and 40–49 years showing the least participants with only 7.1%. On comparison between gender, males demonstrated a higher percentage than females with 57.1% and 42.9%, respectively. The distribution of participants according to education level showed a high percentage of undergraduates (71.4%) and illiterates showed 14.3%, whereas graduates and post graduates share equal percentages of 7.1% each. The participants showed no variation in distribution according to location i.e., rural and urban. However, non-vegetarians (71.4) showed a higher number of DH cases than vegetarians (28.6%).

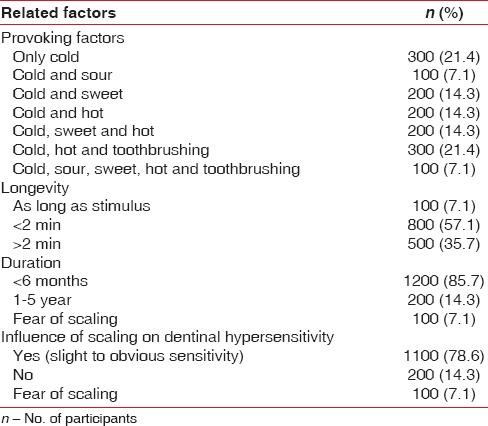

Table 2 shows that the majority of the participants had only cold (21.4%) and cold, hot and tooth-brushing (combination) (21.4%) as the provoking factors (stimulus) for DH whereas, only 7.1% were affected by combination of cold and sour. In the studied population, majority of the participants had <2 min (57.1%) as the longevity of their DH and only 7.1% participants showing longevity to be as long as the stimulus remains. The results also demonstrated that majority of the participants had a duration of <6 months (85.7%) of their DH and a majority had slight to obvious sensitivity (78.6%) as an influence of scaling on DH.

Table 2.

Distribution of participants according to dentin hypersensitivity related factors

Graph 1 show that for majority of the participants the treatments were not undertaken for DH because of time/economic status of the participants, playing as major factors (42.9%), however participants who had undertaken treatment in the past majority showed complete inefficiency (14.2%) and no participant demonstrated a complete elimination of sensitivity.

Graph 1.

Distribution of participants according to the professional treatment for dentinal hypersensitivity

In Graph 2 a distribution of participants on the basis of predisposing factors are demonstrated. The majority of the participants had gingival recession and attrition (28.6%) as the predisposing factor for DH and, combination of gingival recession, attrition and abrasion; combination of gingival recession and abrasion and; only gingival recession accounting for 21.4% followed by only attrition accounting for 7.1%.

Graph 2.

Distribution of participants according to the predisposing factors

The Graph 3 shows the distribution of the participants according to the tooth/teeth involved, with the majority showing mandibular anterior and posterior teeth (28.6%) as the tooth involved in DH.

Graph 3.

Distribution of participants according to the tooth involved

Table 3 shows that out of 1400 patients of DH, 21.4% of the 20–29 years and 14.3% of the 30–39 years had severe discomfort. 35.7% of the males and 14.3% of the females had moderate discomfort. Also, 42.9% of the undergraduates had moderate discomfort. 28.6% of the rural population and 21.4% of the urban population had moderate discomfort. It was also seen that 28.6% of the non-vegetarians and 21.4% of the vegetarians had moderate discomfort. There is a statistically significant association between VAS scores for DH and demographic factors. (P = 0.00).

Table 3.

Association of Visual Analogue Scale scores with demographic factors

Table 4 shows that 7.1% of the 20–29 years and 60–69 years had severe discomfort. 35.7% of the males and 14.3% of the females had moderate discomfort. Also, 42.9% of the undergraduates had moderate discomfort. 28.6% of the rural population and 21.4% of the urban population had moderate discomfort. It was also seen that 28.6% of the non-vegetarians and 21.4% of the vegetarians had moderate discomfort. There is a statistically significant association between VRS scores for DH and demographic factors (P = 0.00).

Table 4.

Association of Verbal Rating Scale scores with demographic factors

DISCUSSION

In this cross-sectional study, the prevalence of DH was observed to be 27.4%, which was calculated on the basis of the studied population.

The females are known to be more affected by DH which is previously shown in several studies.[5,12,13] The present study demonstrated that the males were more affected by the DH than females (1.33:1). The DH between subjects’ age groups was greatest in the age group 20–29 and was least in 60–69 and 40–49. This may be due to development of secondary or sclerotic dentine with advancing age, thereby reducing the DH.[12]

In the present study, the maximum subjects found with DH were either illiterate and/undergraduates which is in accordance with the study conducted by Sood et al.[7] and Que et al.,[14] in which illiterate and low socioeconomic status people were found to have DH. Our study also demonstrates that the maximum people did not undergo any treatment for the DH because of the lack of time, unawareness and/or low economic status.

In a study conducted by Sood et al.,[7] it was demonstrated that majority of DH was observed among the vegetarians than non-vegetarians. Whereas, in the present study it was observed that non-vegetarians were more prone to the DH as compared to vegetarians, which may be because of the intake of highly coarse diet.

The rural and urban population showed no difference in the distribution of the DH in the present study, this observation was not in accordance with the previous studies.[3,7]

The response to cold was cited as the most common stimulus, which was in accordance with the previous studies.[15,16,17,18] The reason may be due to the extreme climate in the state especially in district Jammu. The people tend to have different diet patterns both in winters and summers to adjust with the climate change. There was sensitivity to sweet, sour and tooth brushing stimuli as well seen in our study.

The majority of the subjects suffering from the DH claimed to have endured the condition for <6 months (85.7%) and the longevity of the stimulus to be <2 min (57.1%). The findings were in contrast to the previous findings.[7,17,18]

It was observed in the present study that the teeth often affected by DH were the mandibular anterior and posterior teeth, which is in accordance to the previous literature.[3,4,7,12,15]

Majority of the individuals do not visit a professional for the DH as they might not consider the condition to be too bad to warrant treatment and/it might be due to lack of knowledge.[7,17] Our study demonstrates that the maximum people did not undergo any treatment for the DH and approximately 21.3% individual underwent a professional treatment for DH and out of those majority (14.2%) found the treatment to be ineffective. The reason could be the patient compliance or inefficacy of the treatment.

The previous studies reported that gingival recession is the most predisposing factor associated with DH,[7,4,19,20,21] which is in accordance with the present study. The other predisposing factors are abrasion, and attrition. The reason for hypersensitivity in such conditions is due to the exposure of the root surface to acidic environment of the oral cavity after loss of attachment, causing the exposure of dentinal tubules to the environmental changes.

CONCLUSION

The cross-sectional study found that the prevalence of DH in adults attending the O.P.D in the Govt. Dental hospital at Jammu in North India was 27.4% according to the clinical examination. The study was very much successful in assessing the prevalence of hypersensitivity in the chosen demographic area and its association with the various factors.

Overall, the prevalence of DH decreased with age with minimum prevalence at the age of 60–69 years. The mandibular anterior and posterior teeth were the most commonly affected teeth. Only 21.3% of the patients with sensitive teeth used desensitizing paste; this is indicative of the fact that people in this region are not aware of their dental condition, because of lack of knowledge, they do not seek any treatment.

However, the study was performed in a limited group of population. It could have been useful if a larger sample of population was used. The author recommends more studies to be performed with a much larger sample.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Canadian Advisory Board on Dentin Hypersensitivity. Consensus-based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of dentin hypersensitivity. J Can Dent Assoc. 2003;69:221–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartold PM. Dentinal hypersensitivity: A review. Aust Dent J. 2006;51:212–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rees JS. The prevalence of dentine hypersensitivity in general dental practice in the UK. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:860–5. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027011860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rees JS, Addy M. A cross-sectional study of dentine hypersensitivity. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:997–1003. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.291104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Udoye CI. Pattern and distribution of cervical dentine hypersensitivity in a Nigerian tertiary hospital. Odontostomatol Trop. 2006;29:19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naidu GM, Ram KC, Sirisha NR, Sree YS, Kopuri RK, Satti NR, et al. Prevalence of dentin hypersensitivity and related factors among adult patients visiting a dental school in Andhra Pradesh, Southern India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:ZC48–51. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/9033.4859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sood S, Nagpal M, Gupta S, Jain A. Evaluation of dentine hypersensitivity in adult population with chronic periodontitis visiting dental hospital in Chandigarh. Indian J Dent Res. 2016;27:249–55. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.186239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhaliwal JS, Palwankar P, Khinda PK, Sodhi SK. Prevalence of dentine hypersensitivity: A cross-sectional study in rural Punjabi Indians. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2012;16:426–9. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.100924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Roy PG. Helsinki and the decleration of Helsinki. World Med J. 2004;50:9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collins SL, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. The visual analogue pain intensity scale: What is moderate pain in millimetres? Pain. 1997;72:95–7. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)00005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su-Hwan K, Jun-Beom P, Chul-Woo L, Ki-Tae K, Tae-Il K, Yang-Jo S, et al. The clinical effects of a hydroxyapatite containing toothpaste for dentine hypersensitivity. J Korean Acad Periodontol. 2009;39:87–94. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer C, Fischer RG, Wennberg A. Prevalence and distribution of cervical dentine hypersensitivity in a population in Rio De Janeiro, Brazil. J Dent. 1992;20:272–6. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(92)90043-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dababneh RH, Khouri AT, Addy M. Dentine hypersensitivity-an enigma? A review of terminology, mechanisms, aetiology and management. Br Dent J. 1999;187:606–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Que K, Ruan J, Fan X, Liang X, Hu D. A multi-centre and cross-sectional study of dentine hypersensitivity in china. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:631–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orchardson R, Collins WJ. Clinical features of hypersensitive teeth. Br Dent J. 1987;162:253–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4806096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chabanski MB, Gillam DG, Bulman JS, Newman HN. Prevalence of cervical dentine sensitivity in a population of patients referred to a specialist periodontology department. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:989–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb00525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flynn J, Galloway R, Orchardson R. The incidence of ‘hypersensitive’ teeth in the west of Scotland. J Dent. 1985;13:230–6. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(85)90004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gillam DG, Seo HS, Newman HN, Bulman JS. Comparison of dentine hypersensitivity in selected occidental and oriental populations. J Oral Rehabil. 2001;28:20–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2001.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chabanski MB, Gillam DG, Bulman JS, Newman HN. Clinical evaluation of cervical dentine hypersensitivity in a population of patients referred to a specialist periodontology department: A pilot study. J Oral Rehab. 1997;187:606–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.1997.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taani SD, Awartani F. Clinical evaluation of cervical dentin sensitivity (CDS) in patients attending general dental clinics (GDC) and periodontal specialty clinics (PSC) J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:118–22. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rees JS, Addy M. A cross-sectional study of buccal cervical sensitivity in UK general dental practice and a summary review of prevalence studies. Int J Dent Hyg. 2004;2:64–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5029.2004.00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]