Abstract

Background:

In the present era, demand of beauty and esthetics has increased rapidly. Interdental papilla construction, especially in the esthetic zone, is one of the most challenging tasks. Interdental papilla loss might occur due to several reasons as a consequence of periodontal surgery, trauma, and others.

Aim and Objective:

The present study was aimed to prepare economically feasible injectable form of hyaluronic acid (HA) gel in three different concentrations – 1%, 2%, and 5% HA to evaluate its efficacy in the enhancement of deficient interdental papilla (IDP).

Materials and Methods:

A total of 42 sites (mean age range was 29.6–30.6 years) was categorized into three groups; 1% HA group (16 sites), 2% HA group (14 sites), and 5% HA group (12 sites). Total 35 sites were followed up out of 42 in which 2% HA group included only 7 sites. Both maxillary (17 sites) and mandibular (18 sites) sites were included in this study. HA was injected at 2 mm apical to papillary tip at weekly interval for 3 weeks. The IDP augmentation was measured using UNC-15 probe and modified stent at 1, 3, and 6 months. The photographic analysis was done using Image J software.

Results:

On clinical measurement, 5% of HA showed highly significant enhancement (P = 0.001) of 19.2%, 20.6% 18.2% at 1, 3, and 6 months, respectively. On photographic analysis, 5% of HA showed 41%, 42.9%, and 39.8% at 1, 3, and 6 months, respectively. However, intergroup comparison showed nonsignificant improvement.

Conclusion:

This study results suggest that the use of 5% of HA is effective for interdental deficiency treatment with minimal rebound at the end of 6 months. The modified stent for IDP measurement used in this study for the first time in the literature is highly recommended. The photographic analysis using image J Analyzer serves a useful and dependable tool. Further, long-term clinical studies would throw more insight in this regard.

Keywords: Esthetics, hyaluronic acid, interdental papillary deficiency, modified stent

INTRODUCTION

The esthetic area is defined as the visible area during functioning and includes the anterior maxillary and mandibular teeth.[1] Interdental “black triangles” were considered as the third most disliked and less attractive esthetic problem after caries and crown margins.[2,3] The loss of gingival papillary height results in open gingival embrasures which leads to several problems in phonetics, esthetic concerns, and food impaction.[4,5] This loss of interdental papillae (IDP) commonly known as “black holes”[5,6] or “black triangles.”[7,8] The gingival black space is the distance from the cervical black space to the interproximal contact.[8]

Different surgical and nonsurgical approaches are proposed in the periodontal literature to provide satisfactory IDP reconstruction.[9] Several nonsurgical and surgical techniques for the reconstruction of lost IDP remains elusive. The compromised blood supply, scarring, and trauma in thin gingival biotypes increase the failure risk.[10]

There are several safer and less invasive studies related to the application of commercial hyaluronic acid in IDP e deficiency.[11,12,13,14,15] which are expensive and not readily available in India. Therefore, in the present study, hyaluronic acid (HA) was prepared without adding any crosslinking agents (known to cause allergic reaction). MEDLINE search on comparative studies using different HA concentration on IDP enhancement does not exist. Earlier studies have assessed the IDP augmentation using only photographic analysis. The lack of clinical measurement of IDP improvement was a major lacunae. To overcome the lacuna, a modified stent was prepared to measure the clinical improvement in IDP for the first time. Hence, in the current study, a first attempt was made for clinical and photographic evaluation of IDP-treated sites using different concentrations (1%, 2%, and 5%) of HA injection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study was a human prospective, clinical trial for the treatment of IDP deficiency for 6 months. A total of 42 papillary recession defects in 10 systemically and periodontally healthy controls of both sexes of age group 25–40 years satisfying the determined inclusion criteria were selected. The study protocol was approved by Institutional Review Board (Ref. No. CODS/1977/2015-2016) fulfilling the criteria of RGUHS, India. All patients were informed about the nature of the study, injection procedure involved, potential benefits and risk associated with the injection procedure and written consent were obtained from all patients.

The inclusion criteria included the participants with clinically normal periodontium other than deficient papilla with Cardaropoli Papilla Presence Index (PPI)[16] score 2 and 3 and with full mouth plaque score <10%.[17] The patients with known allergy to hyaluronic acid, poor plaque control, medically compromised, teeth with hopeless prognosis, parafunctional habits, traumatic occlusion, patient who had undergone periodontal plastic surgery for the selected area in the last 1 year, adjacent teeth with caries, fixed prosthesis, or orthodontic appliance, drug-induced gingival overgrowth, pregnant and lactating woman, and smokers were excluded from the study.

The clinical parameters assessed were as follows: Plaque Control Record Index,[17] Gingival Bleeding Index,[18] Modified Gingival Index, and[19] Cardaropoli PPI[16] and pain assessment scale by numeric rating scale (NRS).[20] All clinical measurements were carried out by a single calibrated examiner to ensure an unbiased evaluation and rule out interexaminer variability. Injection procedure was performed by the second operator to avoid intraoperator variation. The selected participants were categorized into three groups in which one of the three different concentrations of HA was injected. Group 1 with 1% HA injection, Group 2 with 2% of HA and Group 3 with 5% of HA. The preparation of injectable form of HA from raw powder was performed in college of Pharmacy. The 1%, 2%, and 5% of HA solutions were prepared by dissolving 10, 20, and 50 mg/ml of HA powder (Herb supply, LLC, LasVegas, NV) in aseptic conditions. The prepared HA were stored in sterile vials closed with a rubber stopper, sealed with an aluminum cap using vial sealer, and stored in cool dry place.

A modified occlusal stent was used to measure IDP measurement and rounded off to the nearest 0.5 mm [Figure 1].[21] An occlusal stent used for vertical probing was modified to measure IDP measurement. The occlusal stents for IDP measurement were fabricated with cold-cure clear acrylic resin on the cast model obtained from the alginate impression. The stent covered the incisal surface of the tooth being treated and extended to incisal surface of at least one tooth in the mesial and distal directions. It also extended apically on the labial and lingual surfaces to cover the coronal third of the teeth.[22] The interdental part of stent was trimmed to the incisal edge from the labial side to place probe parallel to the tooth surface to measure tip of papilla from reference point (apical extent of stent) and the lower border of the stent was marked with black pen to facilitate the easy probe readings, i.e., the millimeter markings on the probe coincides with the black pen mark was recorded and rounded off to nearest millimeter.[21]

Figure 1.

UNC 15 Probe to measure interdental papillae. The occlusal stent modification and black mark at the coronal end of the stent assisted the probe measurement

Clinical and photographic measurements were recorded at baseline, 1, 3, and 6 months. The above-mentioned clinical parameters were recorded using UNC-15 probe (Hu-Friedy, Chicago, IL, U SA).

The selected site was anesthesthetized using lignocaine 2%, 1:80,000 adrenaline and <0.2 ml of the HA gel was injected using insulin syringe (BD Ultra-Fine™ Needle Insulin Syringe) with 0.2 mm (31G) × 6 mm needle at the respective sites 2–3 mm apical to the coronal tip of the papilla[11] [Figure 2]. The area was gently massaged for 1 min. The patient was instructed to avoid the use of dental floss at the treatment sites and use of soft toothbrush coronal to the gingival margin. Injection was repeated on 2nd and 3rd weeks. Patients were followed up for 1, 3, and 6 months.

Figure 2.

Topical injection of hyaluronic acid in interdental papillae

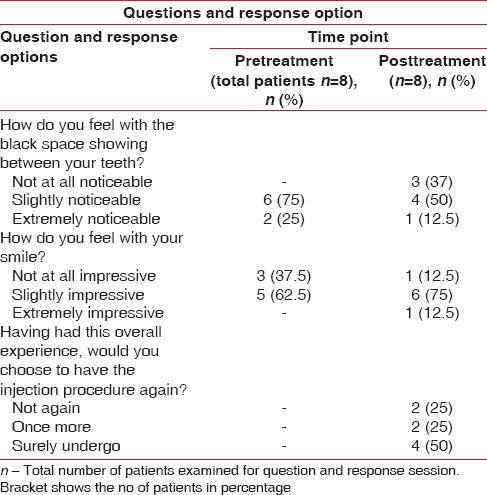

Postoperative adverse reactions, such as severe pain, itching, redness, ulcers to the local area or at lip, granulomatous lesion, swelling, any abnormal patch, tenderness, and bruising to the local site, were inspected from 24 h to 1 week of postinjection. The patient's response was recorded in the prescribed format [Table 1].

Table 1.

Questions and response option

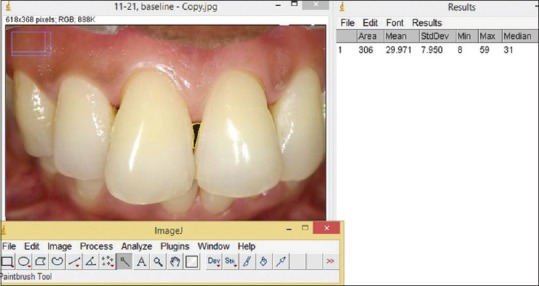

The photographic evaluation of papillary deficiency (black space) was measured as the distance between reference point (apical margin of the stent) and the tip of papilla using Image J software (National Institutes of Health, United States).[12] Using clinical photographs, change in the area of interest was calculated at baseline 1, 3, and 6 months [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Photographic analysis using Image J software

For the first time, two types of measurement, such as clinical and photographic analysis, were done in this study. For clinical assessment, measurement was taken from contact point to tip of the papilla using the fixed reference point (FRP) of stent at baseline, 1, 3, and 6 months. In clinical measurement, the linear measurement from the papillary tip to FRP in the stent was recorded to minimize the errors and was reproducible. This linear measurement recorded the papillary enhancement. The actual change in black space cannot be measured clinically. Therefore, the clinical term for improvement after papillary deficiency treatment was reported as a papillary enhancement rather than black space reduction. Photographically, reduction in black space and clinically reduction in linear measurement were suggestive of papillary enhancement.

Individual papillae were the unit of analysis as suggested by Awartani and Tatakis.[13] In the follow-up period, clinical and photographic parameters were recorded, and the data were subjected to statistical analysis using one-way ANOVA test, repeated measures test, Friedman test, and Kruskal–Wallis test.

RESULTS

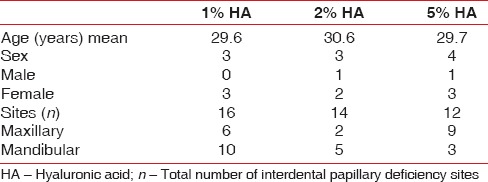

Totally 35 sites were followed up out of 42 sites (mean age range was 29.6–30.6 years) which was divided in three groups; 1% HA of group (16 sites), 2% of HA group (7 sites) and 5% of HA group (12 sites). Both maxillary (17 sites) and mandibular (18 sites) were included in this study. The reason for dropout was that patient did not report follow-up injection. Distribution of sites among three groups was similar (12–16 sites) [Table 2]. The plaque reduction, gingival bleeding, and modified gingival index were nonsignificant in all three groups from baseline to 6 months. The patient response form regarding their esthetic concern, smile and need for treatment is shown in Table 1.

Table 2.

Demographic table

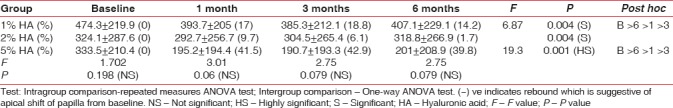

On clinical intrameasurement, in intragroup 1% and 5% of HA showed improvement in papillary enhancement from baseline to different study intervals, i.e., 13.9%, 10.5%, 4.5%, 19.2%, 20.6% and 18.2%, respectively. Nearly 1% of HA showed significant (P = 0.004), and 5% of HA showed highly significant (P = 0.001) improvement in papillary enhancement whereas 2% of HA group did not show any significant improvement (P = 0.125). Intergroup comparison showed nonsignificant improvement [Table 3]. On photographic analysis, intragroup results showed significant black space reduction from baseline to different study intervals in all three groups that is 1% (P = 0.004), 2% (P = 0.004), 5% (P = 0.001). Intergroup comparison revealed no significant difference between the groups. However, 5% HA showed clinically demonstrable enhancement of 41%, 42.9%, and 39.8% at 1, 3, and 6 months, respectively [Table 4].

Table 3.

Stent measurement

Table 4.

Photographic analysis

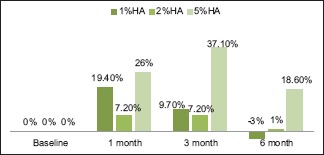

There were three types of post-HA injection outcomes. They were grouped as those sites which showed continuous improvement, improvement, and rebound at different intervals and no improvement from baseline to 6 months [Graphs 1, 2 and Figures 4-6]. The sites with no improvement were found to be least in 5% of HA group followed by 2% of HA and 1% of HA sites. However, it was not statistically significant (P = 0.427).

Graph 1.

Continuous improvement from baseline to 6 months

Graph 2.

Improvement and rebound from baseline to 6 months

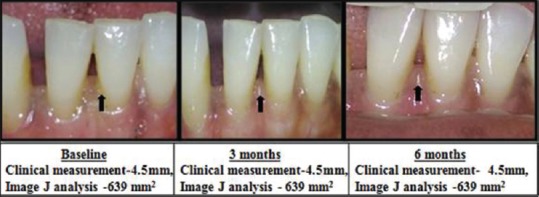

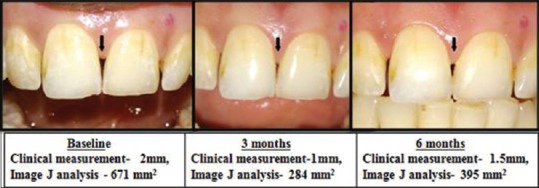

Figure 4.

Continuous Improvement Shown With Clinical Measurement (mm) using stent And Photographic Measurement (area) using image J at different intervals

Figure 6.

No improvement

Figure 5.

Improvement And Rebound Shown With Clinical Measurement (mm) using stent And Photographic Measurement (area) using image J at different intervals

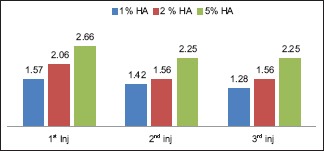

The NRS scale for pain assessment was used and analyzed at different injection frequency. There was no significant (P = 0.096) perception of pain in 1% and 2% of HA groups at 1st, 2nd, and 3rd injection. However, in 5% of HA group, there was pain perception at all three injection frequencies. On intergroup comparison, there was significant pain perception at 1st injection time [Graph 3].

Graph 3.

Pain assessment scale

DISCUSSION

HA is approved by the Federal Food and Drug Administration.[11] It is nonimmunogenic, enzymatically degradable and relatively nonadhesive to cells and protein[23] and capable of interacting with a number of receptors resulting in the activation of signaling cascades that influence cell migration, proliferation, and gene expression.[24]

The results of this study are discussed as follows: in all the three concentrations of HA group, dichotomous plaque levels of 10%–20% and 10% of bleeding score was maintained during the study due to good maintenance by patients. On clinical measurement using modified stent in all the concentrations, 5% of H A group showed higher improvement (18.2%) in the form of papillary enhancement till the end of 6 months than 1% HA (4.5%). At 6 months, there was 7.5% apical shift of papilla from the baseline level. In 5% HA of group, one sites showed 100% improvement. The 2% HA requires to be further studied as the patient did not complete the follow-up. On photographic analysis, all the three concentrations showed improvement at 6 months from baseline. The higher percentage of improvement was shown by 5% HA group (39.8%) and least by 2% HA group (1.7%). In 5% of HA group, one site showed 100% improvement. Hence, while dealing with the IDP deficiency treatment, it is recommended that both clinical and photographic analysis have to be carried out to ascertain finer changes in tiny little IDP area.

Although the intergroup comparison was not statistically significant in papillary enhancement, the clinical papillary enhancement and photographic analysis were highly appreciable in 5% of HA group. Most often, clinical significance needs to be considered than statistically significant. Clinical interpretation of research on treatment outcomes is important because of its influence on clinical decision-making including patient safety and efficacy. Furthermore, statistically significant differences between data sets may not always result in an appropriate change in clinical practice.[25]

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study where modified stent was used to clinically measure the papillary loss. None of the previous studies[11,12,13,14,15] have clinically measured the IDP loss. The occlusal stent modification and black mark at the coronal end of the stent-assisted the measurement which was reproducible and convenient. In the IDP deficiency treatment in diastema cases (lack of contact point), this modified stent would provide a good reference point.

Due to the interdental deficiency, the distance between contact point and papilla tip increases resulting in black space formation. The clinical measurement of black space is not possible as the area has to be measured. Hence, two types of measurement, such as clinical and photographic analysis were done in this study for the first time. In clinical measurement, the linear measurement from the papillary tip to FRP of the stent was recorded to minimize errors, and the measurements were reproducible. This linear measurement provides the papillary deficiency/enhancement. The actual change in black space cannot be measured clinically. Hence, the clinical term for improvement after papillary deficiency treatment needs to be papillary enhancement than black space/black triangle reduction as few authors have used them interchangeably. None of the authors have reported clinical measurement as performed in our study.

Hyaluronic acid degrades naturally in the body, and therefore, the duration of maintenance of the injectable HA gel is critical. In the present study, the post-HA injection outcomes were categorized into three groups to find out clinically suitable HA concentration for IDP deficiency treatment. They were categorized into (1) continuous improvement, (2) improvement and rebound at different intervals and (3) no improvement from baseline to 6 months. In the previous studies, none of the authors have categorized the sites similar to our study. In the current study, three types of clinical outcomes were recorded for the first time in literature. In 1% and 5% HA groups, 3–7 sites showed continuous improvement of 22.3% and 24%, respectively. In all the three concentrations, 5% of HA group showed higher percentage of improvement with less rebound from 3 (37.1%) to 6 months (18.6%). Nearly 1% HA showed maximum rebound of (−3%) at 6 months suggestive of apical shift of papilla from baseline level. In 1%, 2%, and 5% of HA groups, 4, 2, and 3 sites did not show any improvement, respectively. There is a possibility that the injection of HA into the tissues might not have reached the satisfactory level to bring about changes in all the three groups. The three outcomes presented in this study suggested the efficacy of different concentrations of HA at different intervals. It provides a clinical guidance for further HA injections.

Some of the previous studies showed relapse between 4 and 6[13,14] months and partial IDP reconstruction,[14] whereas few studies did not report any relapse.[11,12] Such disparities may relate to the specific material used and the apparent difference in size of the treated defects.[13]

In the present study, the pain perception was measured using NRS. The postinjection pain was least in 1% of HA group and more in 5% HA of group. However, in all the groups, pain perception decreased from 1st to 3rd injections and there were no adverse reactions of different concentration. Mild pain or discomfort was reported in the patients for 24 h at each visit of injection unlike Becker et al. study where all patients considered treatment to be painless. The possible reason for pain could be the highly hygroscopic nature of HA (1 g HA can bind up to 6 L of water)[26] which exerted progressively an external vascular compression and at least partial occlusion of neighboring blood vessels.[27]

No adverse reactions were noticed at the injection site unlike other studies which reported severe pain,[15] swelling,[13,15] tenderness,[13] and granuloma formation.[15] The study participants were asked to respond regarding their black space and esthetic issues in a prescribed format before and after treatment. In the current study, regarding appreciation of smile, 37.5% expressed that their smile was not at all impressive and 62.5% participants expressed as slightly impressive before the IDP deficiency treatment; after treatment, 12.5%, 75%, and 12.5% found their smile not at all impressive, slightly impressive, and extremely impressive. Regarding their interest to persuade the treatment, 50% participants wanted to undergo treatment surely, 25% of them did not want injection, and 25% of participants wanted to try once more. In the current study, 25% and 75% participants found interdental black space extremely and slightly noticeable before and after IDP deficiency treatment, respectively. Whereas 12.5% participants found extremely noticeable, 50% found it noticeable, and 25% participants found it not at all noticeable in posttreatment period [Table 1]. The patient response on black space as esthetic issues, smile nature, and option to get treated showed response variations which could be based on their individual esthetic appreciation and need for correction. The degree of esthetic and functional interference would make an individual to avail the benefit of treatment. In local scenario, the IDP deficiency corrections are mostly up to dentists responsibility to create awareness on black space and its treatment availability. Awartani and Tatakis reported such response form wherein the queries were different from our study.[13]

There are few authors,[11,12,13,14,15] who have used HA injections for IDP deficiency treatment. Their methodology differs from our study regarding the concentration of HA used, no of sites included, commercial preparation with crosslinking agent, number of injection at different time intervals, duration of assessment, and criteria used for inclusion of IDP deficiency participants. None of the authors have used the clinical measurements for expression of the effectiveness of their treatment. Hence, their study reports are presented below, and no effort is made to compare with our study results.

Becker et al.[11] reported 100% improvement in three sites and 88%–97% improvement in eight sites; one site showed 57% improvement. Furthermore, in Becker et al. study, follow-up duration (6–25 months; 25 months for only one patient) and number of injection (1–3 injections) were not same for all the patients. However, in the current study, maximum duration of follow-up was 6 months (at 1 3, and 6 months) and all patients received three injections for successive 3 weeks. Mansouri et al.[12] showed 1%–15%; 12%–83% and 22%–100% improvement at 3 weeks, 3 and 6 months after injection. In Awartani and Tatakis[13] study, the average reduction in black triangle area at 4 and 6 months was 62 and 41%, respectively. Lee et al.[14] reported complete papilla fill in 29 out of 43 sites and 14 sites improved from 39% to 96%. Contrary to the above studies, Bertl et al.[15] found no significant differences in test (HA injection) and control group (saline injection solution) injection groups neither at baseline nor at 3 and 6 months posttreatment. The inclusion of control group, by injecting saline solution is highly questionable. None of the above studies observed IDP deficiency through clinical measurement.

Various factors play a vital role in governing the IDP morphology clinically and histologically. These are underlying osseous support,[28] distance between interproximal contact positions to alveolar bone crest,[29] Interproximal space between teeth,[30] periodontal biotype,[31] tooth morphology,[32] diverging roots and postorthodontic treatment, and[33] patient age.[34,35] The continuous improvement sites would be possibly favored by the above factors than those sites which showed continuous improvement and rebound and no improvement sites. It appears that the papillary enhancement would depend on these factors posttreatment too.

The important clinical issue of this study is that HA formulation can be easily done which is cost-effective. The shelf life of the prepared is 1–2 months. Hence, it is affordable considering the economic status of the Indian population. The procedure of HA injection is simple and tolerable. Till 6 months, 5% of HA was able to maintain enhanced IDP levels successfully in majority of treated sites. Although 1% HA was clinically effective, it did not reach the consistent outcomes of 5% of HA. The clinically appreciable relevance is construction of modified stent for clinical measurement of IDP. The possible shortcoming of the study is number of sites included. Considering the results of this study, 5% of HA is recommended for IDP deficiency treatment. Further studies with large number of sites to confirm the current study results based on gingival thickness are required. The histologic evaluation of HA-injected sites may provide good insight into its action. From the current study results, 5% of HA injections as minimal invasive approaches is recommended for interdental and even for interimplant papillary deficiency treatment.

CONCLUSION

The use of 5% of hyaluronic acid is effective for interdental deficiency treatment which is cost-effective and safe to use. The use of modified stent for clinical improvement assessment of IDP is recommended. Further, long-term studies would throw more insight with this regard. Further histologic studies are required to assess the mechanism of hyaluronic action.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yu YC, Alamri A, Francisco H, Cho SC, Hirsch S. Interdental papilla length and the perception of aesthetics in asymmetric situations. Int J Dent 2015. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/125146. 125146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunliffe J, Pretty I. Patients’ ranking of interdental “black triangles” against other common aesthetic problems. Eur J Prosthodont Restor Dent. 2009;17:177–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kokich VG. Esthetics: The orthodontic-periodontic restorative connection. Semin Orthod. 1996;2:21–30. doi: 10.1016/s1073-8746(96)80036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahale SA, Jagdhane VN. Anatomiv variables affecting interdental papilla. J Int Clin Res Organ. 2013;5:14–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pradeep AR, Karthikeyan BV. Peri-implant papilla reconstruction: Realities and limitations. J Periodontol. 2006;77:534–44. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azzi R, Etienne D, Carranza F. Surgical reconstruction of the interdental papilla. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1998;18:466–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blatz MB, Hurzeler MB, Strub JR. Reconstruction of the lost interproximal papilla – Presentation of surgical and nonsurgical approaches. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1999;19:395406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ko-Kimura N, Kimura-Hayashi M, Yamaguchi M, Ikeda T, Meguro D, Kanekawa M, et al. Some factors associated with open gingival embrasures following orthodontic treatment. Aust Orthod J. 2003;19:19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prato GP, Rotundo R, Cortellini P, Tinti C, Azzi R. Interdental papilla management: A review and classification of the therapeutic approaches. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2004;24:246–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muthukumar S, Rangarao S. Surgical augmentation of interdental papilla – A case series. Contemp Clin Dent. 2015;6:S294–8. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.166836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Becker W, Gabitov I, Stepanov M, Kois J, Smidt A, Becker BE, et al. Minimally invasive treatment for papillae deficiencies in the esthetic zone: A pilot study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2010;12:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8208.2009.00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mansouri SS, Ghasemi M, Salmani Z, Shams N. Clinical application of hyaluronic acid gel for reconstruction of interdental papilla at the esthetic zone. J Islamic Dent Assoc Iran. 2013;25:152–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Awartani FA, Tatakis DN. Interdental papilla loss: Treatment by hyaluronic acid gel injection: A case series. Clin Oral Investig. 2016;20:1775–80. doi: 10.1007/s00784-015-1677-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee WP, Kim HJ, Yu SJ, Kim BO. Six month clinical evaluation of interdental papilla reconstruction with injectable hyaluronic acid gel using an image analysis system. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2016;28:221–30. doi: 10.1111/jerd.12216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bertl K, Gotfredsen K, Jensen SS, Bruckmann C, Stavropoulos A. Can hyaluronan injections augment deficient papillae at implant-supported crowns in the anterior maxilla? A randomized controlled clinical trial with 6 months follow-up. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2017;28:1054–61. doi: 10.1111/clr.12917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cardaropoli D, Re S, Corrente G. The papilla presence index (PPI): A new system to assess interproximal papillary levels. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2004;24:488–92. doi: 10.11607/prd.00.0596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Leary TJ, Drake RB, Naylor JE. The plaque control record. J Periodontol. 1972;43:38. doi: 10.1902/jop.1972.43.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ainamo J, Bay I. Problems and proposals for recording gingivitis and plaque. Int Dent J. 1975;25:229–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lobene RR, Weatherford T, Ross NM, Lamm RA, Menaker L. A modified gingival index for use in clinical trials. Clin Prev Dent. 1986;8:3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T, French M. Measures of adult pain: Visual analog scale for pain (VAS pain), numeric rating scale for pain (NRS pain), McGill pain questionnaire (MPQ), short-form McGill pain questionnaire (SF-MPQ), chronic pain grade scale (CPGS), short form-36 bodily pain scale (SF-36 BPS), and measure of intermittent and constant osteoarthritis pain (ICOAP) Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63(Suppl 11):S240–52. doi: 10.1002/acr.20543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Srinivas M, Chethana KC, Padma R, Suragimath G, Anil M, Pai BS, et al. A study to assess and compare the peripheral blood neutrophil chemotaxis in smokers and non smokers with healthy periodontium, gingivitis, and chronic periodontitis. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2012;16:54–8. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.94605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vandana KL, Gupta I. The location of cemento enamel junction for CAL measurement: A clinical crisis. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2009;13:12–5. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.51888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saranraj P, Naidu MA. Hyaluronic acid production and its applications – A review. Int J Pharm Biol Arch. 2013;4:853–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor KR, Trowbridge JM, Rudisill JA, Termeer CC, Simon JC, Gallo RL, et al. Hyaluronan fragments stimulate endothelial recognition of injury through TLR4. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:17079–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310859200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Page P. Beyond statistical significance: Clinical interpretation of rehabilitation research literature. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014;9:726–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sutherland IW. Novel and established applications of microbial polysaccharides. Trends Biotechnol. 1998;16:41–6. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(97)01139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bertl K, Gotfredsen K, Jensen SS, Bruckmann C, Stavropoulos A. Adverse reaction after hyaluronan injection for minimally invasive papilla volume augmentation. A report on two cases. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2017;28:871–6. doi: 10.1111/clr.12892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tal H. Relationship between the interproximal distance of roots and the prevalence of intrabony pockets. J Periodontol. 1984;55:604–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.1984.55.10.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tarnow DP, Magner AW, Fletcher P. The effect of the distance from the contact point to the crest of bone on the presence or absence of the interproximal dental papilla. J Periodontol. 1992;63:995–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.12.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cho HS, Jang HS, Kim DK, Park JC, Kim HJ, Choi SH, et al. The effects of interproximal distance between roots on the existence of interdental papillae according to the distance from the contact point to the alveolar crest. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1651–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.060023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kois JC. Predictable single tooth peri-implant esthetics: Five diagnostic keys. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2001;22:199–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmad I. Anterior dental aesthetics: Gingival perspective. Br Dent J. 2005;199:195–202. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burke S, Burch JG, Tetz JA. Incidence and size of pretreatment overlap and posttreatment gingival embrasure space between maxillary central incisors. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1994;105:506–11. doi: 10.1016/S0889-5406(94)70013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vandana KL, Savitha B. Thickness of gingiva in association with age, gender and dental arch location. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:828–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van der Velden U. Effect of age on the periodontium. J Clin Periodontol. 1984;11:281–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1984.tb01325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]