Abstract

Background:

Increased oxidative stress has emerged as one of the prime factors in the pathogenesis of periodontitis. Hence, antioxidant therapy may become a promising tool in the treatment of periodontal disease. Uric acid (UA) being a major antioxidant in saliva can be used as a marker to assess the total antioxidant capacity.

Aim:

The aim of the study was to investigate the influence of orally administered antioxidants (lycopene and green tea extract) on periodontal health and salivary UA levels in gingivitis patients as an adjunct to scaling and root planing (SRP).

Materials and Methods:

Thirty systemically healthy participants having generalized gingivitis were randomly distributed into two groups. Control group participants received full mouth oral prophylaxis, while test group participants received oral lycopene and green tea extract (CLIK®) for 45 days along with complete oral prophylaxis. Plaque index (PI), sulcular bleeding index (SBI), and salivary UA levels were evaluated at baseline and 45 days after SRP. Data were analyzed with t-test, using SPSS software (PASW, Windows version 18.0).

Results:

Both treatment groups demonstrated statistically highly significant (P ≤ 0.001) reduction in plaque and SBI. After treatment, a highly significant increase (P ≤ 0.001) in the test group and significant (P ≤ 0.05) increase in the control group was observed for salivary UA levels. Posttreatment comparison between test and control group delineated statistically significant results in PI (P ≤ 0.001), SBI (P ≤ 0.001), and salivary UA levels (P ≤ 0.01).

Conclusion:

Lycopene with green tea extract may prove to be a promising adjunctive prophylactic and therapeutic modality in the treatment of gingivitis patients. However, further studies are needed to evaluate the additive effect of antioxidants with routine oral prophylaxis therapy.

Keywords: Antioxidants, gingivitis, lycopene, oxidative stress, uric acid

INTRODUCTION

Periodontal disease is an inflammatory event leading to progressive deterioration of the periodontal attachment apparatus, eventually causing tooth loss. Gingivitis is its mildest form, manifesting as inflammation of gingiva. The primary etiological factor causing periodontal disease is periodontal pathogens; however, multiple factors are involved in its pathogenesis. Oxidative stress is one of them; although it is not clear, whether it is a cause or consequence of the disease process.[1] This is supported by scientific literature which demonstrated higher levels of oxidative damage products of DNA, lipids, and proteins[2,3] and lower level of antioxidant enzymes in chronic periodontitis inflammation.[4,5,6]

Oxidative stress occurs; when during an inflammatory response, the reactive oxygen species (ROS) overwhelm the endogenous antioxidant defense system of body.[7,8] ROS is generated by polymorphonuclear leukocyte in the process of oxidative burst during phagocytosis. Inflammatory process could be attenuated by exogenous antioxidants in the form of dietary supplements which strengthens the body's antioxidant defense system. However, current evidence-based guidelines provide sparse recommendations for the nutritional management of participants with periodontal disease.

Lycopene is an effective natural antioxidant and most efficient biological carotenoid exhibiting highest physical quenching rate with singlet oxygen (twice as high as that of beta-carotene and ten times higher than that of α-tocopherol).[9] It reverses the DNA damage induced by hydrogen peroxide. Serum and tissue lycopene levels are inversely related to chronic disease risk. Lycopene participates in a cascade of chemical reactions, protecting critical cellular biomolecules, including lipids, proteins, and DNA[10] and believed to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, osteoporosis, and in some cases, even male infertility.[9]

Green tea contains many polyphenolic components known as catechins such as epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) and epigallocatechin, which possess higher antioxidant activity than Vitamin C and E. Their antioxidant action involves scavenging of ROS or chelation of transition metals while indirectly, they upregulate Phase II antioxidant enzymes.[11] Catechin has been shown to inhibit the growth of Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, and Prevotella nigrescens and the adherence of P. gingivalis onto human buccal epithelial cells in in vitro studies.[12] Recently, EGCG has been shown to downregulate the activity and expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) as MMP-2 and MMP-9 (collagenase and gelatinase) by suppressing the phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase involved in mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway.[13] In addition, green tea may restrict the bone loss in periodontitis patients as EGCG has been shown to inhibit the osteoclast formation and it induces the apoptotic cell death of bone-resorbing osteoclast cells in a dose-dependent manner.[13] In the present study, we used a commercially available combination of 100% natural lycopene with green tea extract as an antioxidant supplement.

Uric acid (UA) is the major antioxidant in saliva with ascorbic acid being secondary and imparts approximately 70% of salivary total antioxidant capacity (TAC).[14] It is a widely used biomarker to assess the antioxidant potential of body fluids and has displayed direct relation to periodontal health.[15] The aim of our study was to investigate the influence of orally administered lycopene and green tea extract as an adjunct to scaling and root planing (SRP) in gingivitis patients by evaluating its effect on clinical parameters and salivary UA levels.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This is a prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial study. Thirty systemically healthy participants (age range 18–40 years) having generalized gingivitis with probing depth <3 mm, plaque index (PI)[16] < 1, and no loss of attachment and bone loss assessed radiographically with orthopantomograph were enrolled for the study with no gender discrimination. Sample size was determined before the study by statistician. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of college committee on human studies. All participants received detailed information on the study and informed written consent was read and signed, after fulfilling the selection criteria. Participants with systemic illness, having attachment loss, smokers, and who received antibiotics/antioxidant therapy in the past 3 months were excluded from the study. Females during puberty, ovulation, pregnancy, and lactation as elicited in history were ruled out as there is an increase in the production of sex steroid hormones which may represent gingivitis, increased bleeding on probing, gingival crevicular fluid flow, change in gingival microbial flora, and gingival enlargement.[17]

Participants were randomly assigned equally (n = 15) into two groups (test and control) using lottery method. Full mouth SRP was performed in both the groups and oral hygiene instructions were given. Periodontal assessment at baseline 1 h after SRP was done with clinical parameters (modified Quigley-Hein PI[18] and sulcular bleeding index [SBI][19]) by a single examiner. The modified Quigley-Hein PI provided a comprehensive method for evaluating plaque control procedures adopted by participants and SBI indicated gingival inflammation. Test group was prescribed, the commercially available anti-oxidant, CLIK® (Idem Healthcare Pvt. Limited) containing natural lycopene (16 mg) with green tea extract (300 mg). The patient was instructed to take the capsule once daily for 45 days as per recommended dose. Postoperative clinical parameters and UA estimation in saliva samples were done after 45 days by the same examiner.

Clinical evaluation

Modified Quigley-Hein PI (Turesky S et al.,)[18] and SBI[19] were recorded at six sites per tooth using a primary care provider University of North Carolina 15 periodontal probe (Hu-Friedy, Chicago, IL, USA) at baseline (1 h after SRP) and after 45 days.

Saliva collection

Sample collection was done for both the groups at baseline and at 45th day. From each patient, 5 ml of unstimulated saliva (to avoid dilution of saliva) was collected in sterile saliva collecting bottles by allowing saliva to passively flow into them [Figure 1]. All samples were stored at 2°C–8°C in airtight containers.

Figure 1.

Labeled collection tubes for saliva sampling

Uric acid estimation

UA estimation was carried by commercially available ELISA kit (Sincere®) [Figure 2] according to the manufacturer's instruction, and readings were recorded through ELISA reader.

Figure 2.

ELISA kit (Sincere®) for uric acid estimation

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with t-test, using SPSS software (PASW, Windows version 18.0). Intra- and inter-group differences were analyzed using paired and unpaired t-test, respectively.

RESULTS

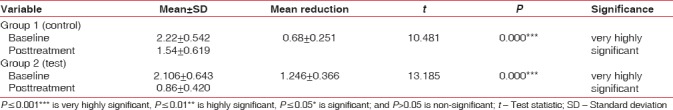

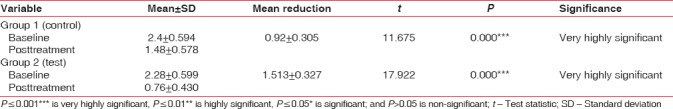

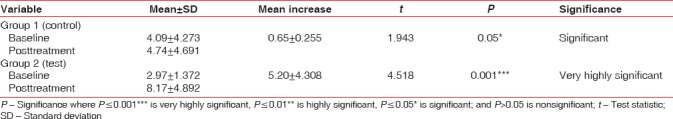

Intragroup comparison in both the groups as shown in Tables 1 and 2 revealed very highly significant (P ≤ 0.001) decrease in both modified Quigley-Hein plaque and SBI from baseline to 45 days. After treatment, very highly significant increase (P ≤ 0.001) in test group and significant (P ≤ 0.05) increase in control group were observed in salivary UA levels [Table 3].

Table 1.

Intragroup comparison of test and control group for modified plaque index immediately after scaling and root planing (baseline) and at 45th day after scaling and root planing/antioxidant supplementation (posttreatment) by paired t-test

Table 2.

Intragroup comparison of test and control group for sulcular bleeding index immediately after scaling and root planing (baseline) and at 45th day after scaling and root planing/antioxidant supplementation (posttreatment) by paired t-test

Table 3.

Intragroup comparison of test and control group for uric acid level (mg/dL) in saliva immediately after scaling and root planing (baseline) and at 45th day after scaling and root planing/antioxidant supplementation (posttreatment) by paired t-test

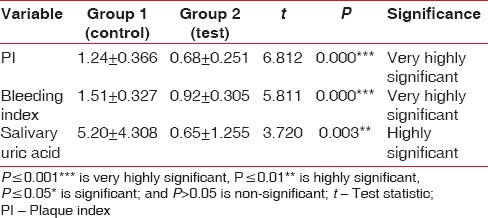

Intergroup comparison between test and control group was done using unpaired t-test. The difference in mean scores of modified Quigley-Hein PI and SBI was significantly higher (P ≤ 0.001) in test group as compared to control group, depicting a greater improvement in gingival status of test than control group. Posttreatment salivary UA levels were significantly higher (P = 0.003) in the test group, demonstrating enhanced antioxidant profile and TAC on receiving systemic antioxidants compared to control group without antioxidant supplements [Table 4].

Table 4.

Intergroup comparison of mean changes in plaque index, bleeding index, and salivary uric acid level (mg/dL) from baseline to 45 days posttreatment by unpaired t-test

DISCUSSION

Lycopene is the most predominant carotenoid in human plasma. It is an acyclic isomer of beta-carotene as it contains conjugated double bonds in high proportion. It is considered as one of the most potent antioxidants in saliva.[20,21] Various experimental studies were carried out to evaluate the impact of dietary lycopene on a number of periodontal variables. The common essence perceptible in these interventional studies was that the ingestion of tomatoes containing natural lycopene improves levels of antioxidants in plasma.[22,23] However, Hininger et al. reported no direct influence of supplementation of β-carotene, lutein, or lycopene on oxidative stress, concluding that carotenoid supplementation does not lead to significantly measurable improvement in antioxidant defenses in apparently healthy participants.[24]

Green tea, one of the most extensively consumed beverages,[25] has the highest concentration of polyphenols which have strong antioxidant properties.[26] Earlier studies have demonstrated that polyphenols reduce MMPs and induce apoptotic cell death of osteoclast, inhibiting bone and tissue destruction in periodontitis.[12] Tagashira et al.[27] and Sakanaka et al. demonstrated that the presence of green tea polyphenols inhibits the cellular adherence of microbes to buccal mucous membrane and growth of P. gingivalis. An animal study showed that green tea extract suppresses the onset of loss of attachment and alveolar bone resorption in a rat model of experimental periodontitis.[28]

Antioxidant effects of lycopene and green tea have been shown to have beneficial effects on periodontal health as it reduces oxidative stress, improves the antioxidant status, and decreases markers of inflammation.[29,30,31,32,33,34] Green tea and lycopene have proved effective in periodontitis patients when used as topical agents.[35] Behfarnia et al. showed that the green tea chewing gum improved the SBI and approximal PI and effectively reduced the level of Interleukin-1β in participants with gingivitis.[36] In an in vitro study, Gadagi et al. revealed a reduction in pocket probing depth and clinical attachment level in the group receiving green tea extract as local drug delivery. Furthermore, prevalence of P. gingivalis reduced from baseline (75%) to 4th week (25%).[37]

In the present study, we found a direct positive correlation between periodontal health and adjunctive antioxidant supplementation (lycopene + green tea extract) with nonsurgical therapy (SRP). Improvement in clinical parameters was found to be statistically significant in both groups following therapy compared to baseline. Although SRP is a standard means of controlling inflammation,[38] the improvement in test group receiving antioxidant therapy were statistically significant (P = 0.001) and greater as compared to the control group.

These results are in accordance with earlier studies which have reported inverse association between periodontal disease and antioxidant (lycopene and green tea) intake.[39,40,41,42,43,44] Supplementation with lycopene and green tea reported to result in reduction in mean pocket depth,[45] mean clinical attachment level,[45,46] bleeding on probing,[45] and halitosis.[47]

UA plays a major role as an antioxidant present in the whole saliva.[48,49] UA levels have been reported to be directly correlated with local and systemic TAC levels.[15] Earlier studies have proved that chronic periodontitis patients have lower levels of UA.[50,51] In the present study, we found that supplementation with lycopene and green tea extract resulted in an increase in mean salivary UA levels. In a recent systemic review, Zhang et al. concluded that drinking green tea might be positively associated with the serum UA level; however, current literature does not provide enough evidence establishing this hypothesis.[52] On the contrary, some authors demonstrated inverse relation of UA levels with circulating carotenoids including lycopene[53] and green tea.[54,55,56] These results indicate that nonsurgical therapy augmented with antioxidant supplementation resulted in improved clinical parameters and salivary UA levels. Inhibition of plaque formation and reduction in inflammation of gingiva reflects the beneficial contribution of antioxidants and induction of healing cascade in gingival tissues.

CONCLUSION

The present study concludes that oral lycopene and green tea extract supplementation is positively associated with salivary UA levels and plays an important role in the management of gingivitis. Although our study emphasized on gingivitis, whose results can be evaluated in 4–6 weeks, further longitudinal studies with larger sample size coupled with other inflammatory markers are required to establish the role of antioxidant therapy in periodontal diseases. Focus should be laid on research and nutritional supplementation of exogenous antioxidants in the management of gingivitis and periodontitis.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study was supported by Idem Pvt. Ltd. by providing test medicine.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr. Geetika Arora, Reader, Department of Community Dentistry, Inderprastha Dental College and Hospital, Sahibabad, Uttar Pradesh, for statistical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Iannitti T, Rottigni V, Palmieri B. Role of free radicals and antioxidant defences in oral cavity-related pathologies. J Oral Pathol Med. 2012;41:649–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2012.01143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Su H, Gornitsky M, Velly AM, Yu H, Benarroch M, Schipper HM, et al. Salivary DNA, lipid, and protein oxidation in nonsmokers with periodontal disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:914–21. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Aiuto F, Nibali L, Parkar M, Patel K, Suvan J, Donos N, et al. Oxidative stress, systemic inflammation, and severe periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2010;89:1241–6. doi: 10.1177/0022034510375830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trivedi S, Lal N, Mahdi AA, Mittal M, Singh B, Pandey S, et al. Evaluation of antioxidant enzymes activity and malondialdehyde levels in patients with chronic periodontitis and diabetes mellitus. J Periodontol. 2014;85:713–20. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.130066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bains VK, Bains R. The antioxidant master glutathione and periodontal health. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2015;12:389–405. doi: 10.4103/1735-3327.166169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeidán-Chuliá F, Gelain DP, Kolling EA, Rybarczyk-Filho JL, Ambrosi P, Terra SR, et al. Major components of energy drinks (caffeine, taurine, and Guarana) exert cytotoxic effects on human neuronal SH-SY5Y cells by decreasing reactive oxygen species production. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:791–5. doi: 10.1155/2013/791795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bazzano LA, He J, Ogden LG, Loria CM, Vupputuri S, Myers L, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of cardiovascular disease in US adults: The first national health and nutrition examination survey epidemiologic follow-up study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:93–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krauss RM, Eckel RH, Howard B, Appel LJ, Daniels SR, Deckelbaum RJ, et al. AHA dietary guidelines: Revision 2000: A statement for healthcare professionals from the nutrition committee of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2000;102:2284–99. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.18.2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Mascio P, Kaiser S, Sies H. Lycopene as the most efficient biological carotenoid singlet oxygen quencher. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1989;274:532–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(89)90467-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman M. Anticarcinogenic, cardioprotective, and other health benefits of tomato compounds lycopene, α-tomatine, and tomatidine in pure form and in fresh and processed tomatoes. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61:9534–50. doi: 10.1021/jf402654e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forester SC, Lambert JD. The role of antioxidant versus pro-oxidant effects of green tea polyphenols in cancer prevention. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2011;55:844–54. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201000641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakanaka S, Aizawa M, Kim M, Yamamoto T. Inhibitory effects of green tea polyphenols on growth and cellular adherence of an oral bacterium, Porphyromonas gingivalis. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1996;60:745–9. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niki E. Assessment of antioxidant capacity in vitro and in vivo . Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49:503–15. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore S, Calder KA, Miller NJ, Rice-Evans CA. Antioxidant activity of saliva and periodontal disease. Free Radic Res. 1994;21:417–25. doi: 10.3109/10715769409056594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lissi E, Salim-Hanna M, Pascual C, del Castillo MD. Evaluation of total antioxidant potential (TRAP) and total antioxidant reactivity from luminol-enhanced chemiluminescence measurements. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;18:153–8. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)00117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Löe H. The gingival index, the plaque index and the retention index systems. J Periodontol. 1967;38:610–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1967.38.6.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markou E, Eleana B, Lazaros T, Antonios K. The influence of sex steroid hormones on gingiva of women. Open Dent J. 2009;3:114–9. doi: 10.2174/1874210600903010114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turesky S, Gilmore ND, Glickman I. Reduced plaque formation by chlormethyl analogue of victamine C. J Periodontol. 1970;41:41–3. doi: 10.1902/jop.1970.41.41.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mühlemann HR, Son S. Gingival sulcus bleeding – A leading symptom in initial gingivitis. Helv Odontol Acta. 1971;15:107–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi J, Le Maguer M. Lycopene in tomatoes: Chemical and physical properties affected by food processing. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2000;20:293–334. doi: 10.1080/07388550091144212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riccioni G, Mancini B, Di Ilio E, Bucciarelli T, D’Orazio N. Protective effect of lycopene in cardiovascular disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2008;12:183–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hadley CW, Clinton SK, Schwartz SJ. The consumption of processed tomato products enhances plasma lycopene concentrations in association with a reduced lipoprotein sensitivity to oxidative damage. J Nutr. 2003;133:727–32. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.3.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fröhlich K, Kaufmann K, Bitsch R, Böhm V. Effects of ingestion of tomatoes, tomato juice and tomato purée on contents of lycopene isomers, tocopherols and ascorbic acid in human plasma as well as on lycopene isomer pattern. Br J Nutr. 2006;95:734–41. doi: 10.1079/bjn20051657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hininger IA, Meyer-Wenger A, Moser U, Wright A, Southon S, Thurnham D, et al. No significant effects of lutein, lycopene or beta-carotene supplementation on biological markers of oxidative stress and LDL oxidizability in healthy adult subjects. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20:232–8. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2001.10719037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang CS, Wang X, Lu G, Picinich SC. Cancer prevention by tea: Animal studies, molecular mechanisms and human relevance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:429–39. doi: 10.1038/nrc2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin YS, Tsai YJ, Tsay JS, Lin JK. Factors affecting the levels of tea polyphenols and caffeine in tea leaves. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:1864–73. doi: 10.1021/jf021066b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tagashira M, Uchiyama K, Yoshimura T, Shirota M, Uemitsu N. Inhibition by hop bract polyphenols of cellular adherence and water-insoluble glucan synthesis of mutans Streptococci. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1997;61:332–5. doi: 10.1271/bbb.61.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshinaga Y, Ukai T, Nakatsu S, Kuramoto A, Nagano F, Yoshinaga M, et al. Green tea extract inhibits the onset of periodontal destruction in rat experimental periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 2014;49:652–9. doi: 10.1111/jre.12147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bose KS, Agrawal BK. Effect of lycopene from cooked tomatoes on serum antioxidant enzymes, lipid peroxidation rate and lipid profile in coronary heart disease. Singapore Med J. 2007;48:415–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacob K, Periago MJ, Böhm V, Berruezo GR. Influence of lycopene and Vitamin C from tomato juice on biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation. Br J Nutr. 2008;99:137–46. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507791894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bub A, Watzl B, Abrahamse L, Delincee H, Adam S, Wever J, et al. Moderate intervention with carotenoid-rich vegetable products reduces lipid peroxidation in men. J Nutr. 2000;130:2200–6. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.9.2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chandra RV, Srinivas G, Reddy AA, Reddy BH, Reddy C, Nagarajan S, et al. Locally delivered antioxidant gel as an adjunct to nonsurgical therapy improves measures of oxidative stress and periodontal disease. J Periodontal Implant Sci. 2013;43:121–9. doi: 10.5051/jpis.2013.43.3.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reddy PV, Ambati M, Koduganti R. Systemic lycopene as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in chronic periodontitis patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2015;5:S25–31. doi: 10.4103/2231-0762.156520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Szulińska M, Stępień M, Kręgielska-Narożna M, Suliburska J, Skrypnik D, Bąk-Sosnowska M, et al. Effects of green tea supplementation on inflammation markers, antioxidant status and blood pressure in NaCl-induced hypertensive rat model. Food Nutr Res. 2017;61:1295525. doi: 10.1080/16546628.2017.1295525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kudva P, Tabasum ST, Shekhawat NK. Effect of green tea catechin, a local drug delivery system as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in chronic periodontitis patients: A clinicomicrobiological study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2011;15:39–45. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.82269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Behfarnia P, Aslani A, Jamshidian F, Noohi S. The efficacy of green tea chewing gum on gingival inflammation. J Dent (Shiraz) 2016;17:149–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gadagi JS, Chava VK, Reddy VR. Green tea extract as a local drug therapy on periodontitis patients with diabetes mellitus: A randomized case-control study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2013;17:198–203. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.113069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryan ME. Nonsurgical approaches for the treatment of periodontal diseases. Dent Clin North Am. 2005;49:611–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2005.03.010. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chandra RV, Prabhuji ML, Roopa DA, Ravirajan S, Kishore HC. Efficacy of lycopene in the treatment of gingivitis: A randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2007;5:327–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharma S, Bhuyan L, Ramachandra S, Sharma S, Dash KC, Dhull KS. Effects of green tea on periodontal health: A prospective clinical study. J Int Oral Health. 2017;9:39–44. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hirasawa M, Takada K, Makimura M, Otake S. Improvement of periodontal status by green tea catechin using a local delivery system: A clinical pilot study. J Periodontal Res. 2002;37:433–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2002.01640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramfjord SP, Caffesse RG, Morrison EC, Hill RW, Kerry GJ, Appleberry EA, et al. 4 modalities of periodontal treatment compared over 5 years. J Clin Periodontol. 1987;14:445–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1987.tb02249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deshpande N, Deshpande A, Mafoud S. Evaluation of intake of green tea on gingival and periodontal status: An experimental study. J Interdiscip Dent. 2012;2:108–12. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arora N, Avula H, Avula JK. The adjunctive use of systemic antioxidant therapy (lycopene) in nonsurgical treatment of chronic periodontitis: A short-term evaluation. Quintessence Int. 2013;44:395–405. doi: 10.3290/j.qi.a29188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kushiyama M, Shimazaki Y, Murakami M, Yamashita Y. Relationship between intake of green tea and periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 2009;80:372–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Belludi SA, Verma S, Banthia R, Bhusari P, Parwani S, Kedia S, et al. Effect of lycopene in the treatment of periodontal disease: A clinical study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2013;14:1054–9. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaneko K, Shimano N, Suzuki Y, Nakamukai M, Ikazaki R. Effects of tea catechins on oral odor and dental plaque. Oral Ther Pharmacol. 1993;12:189–97. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kutzing MK, Firestein BL. Altered uric acid levels and disease states. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:1–7. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.129031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Soukup M, Biesiada I, Henderson A, Idowu B, Rodeback D, Ridpath L, et al. Salivary uric acid as a noninvasive biomarker of metabolic syndrome. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2012;4:14. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Banu S, Jabir NR, Mohan R, Manjunath NC, Kamal MA, Kumar KR, et al. Correlation of toll-like receptor 4, interleukin-18, transaminases, and uric acid in patients with chronic periodontitis and healthy adults. J Periodontol. 2015;86:431–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2014.140414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fatima G, Uppin RB, Kasagani S, Tapshetty R, Rao A. Comparison of salivary uric acid level among healthy individuals without periodontitis with that of smokers and non-smokers with periodontitis. J Adv Oral Res. 2016;7:24–8. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang Y, Cui Y, Li XA, Li LJ, Xie X, Huang YZ, et al. Is tea consumption associated with the serum uric acid level, hyperuricemia or the risk of gout? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18:95. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1456-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ruggiero C, Cherubini A, Guralnik J, Semba RD, Maggio M, Ling SM, et al. The interplay between uric acid and antioxidants in relation to physical function in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1206–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01260.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Curb JD, Reed DM, Kautz JA, Yano K. Coffee, caffeine, and serum cholesterol in Japanese men in Hawaii. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;123:648–55. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chatzistamatiou E, Vagena IB, Konstantinidis D, Memo G, Moustakas G, Markou1 M, et al. Dietary patterns in hyperuricemic hypertensives. J Hypertens. 2015;1:e505–6. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jatuworapruk K, Srichairatanakool S, Ounjaijean S, Kasitanon N, Wangkaew S, Louthrenoo W, et al. Effects of green tea extract on serum uric acid and urate clearance in healthy individuals. J Clin Rheumatol. 2014;20:310–3. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]