Abstract

Background: Due to the emerging trend of alternative medicine, patients inquire about natural remedies to alleviate their symptoms. Dermatologists should be aware of the efficacy and safety of topical botanical treatments available on the market. Mahonia aquifolium, native to the United States, has been recently shown to have anti-inflammatory properties useful in cutaneous disorders. Objective: Our aim was to review clinical trials that assess the efficacy and safety of Mahonia aquifolium in cutaneous disorders. Design: We searched PubMed, MEDLINE, and the Web of Science databases and performed a manual search of clinical trials in the references. We excluded in vivo and in vitro animal trials. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool. Results: Of the 502 articles identified, eight met the inclusion criteria. Specifically, seven trials studied the effects of Mahonia aquifolium in psoriasis and one studied that in atopic dermatitis. Clinical trials have not been identified in any other cutaneous disorder using this plant extract. Risk of bias of included trials were either unclear or low risk. Five of seven studies showed a statistically significant improvement with Mahonia aquifolium in psoriasis, while one study showed efficacy in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Conclusion: Several studies have shown that Mahonia aquifolium leads to a statistically significant improvement of symptoms in psoriasis and atopic dermatitis with minimal side effects.

Keywords: Dermatology, herbal, holistic medicine, randomized clinical trials

EMERGING AUTHORS IN DERMATOLOGY.

The editors of JCAD are pleased to present this bi-annual column as a means to recognize select medical students, PhD candidates, and other young investigators in the field of dermatology for their efforts in scientific writing. We hope that the publication of their work encourages these and other emerging authors to continue their efforts in seeking new and better methods of diagnosis and treatments for patients in dermatology.

Psoriasis and atopic dermatitis are common chronic inflammatory cutaneous disorders. Psoriasis is characterized by erythematous scaling plaques most commonly found on the scalp, extensor surfaces, and lower back,1 while atopic dermatitis is characterized by pruritic eczematous lesions associated with allergic triggers.2 Th17 lymphocytes play a key role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis, producing cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22, which induce keratinocyte proliferation. Tumor necrosis factor alpha accelerates the infiltration of inflammatory cells to the area, while antimicrobial peptides expressed in psoriatic skin lesions further activate dendritic cells, contributing to development of inflammation.3 The key inflammatory mediators involved in atopic dermatitis consist of IL4, IL-5, IL-13, and Th2 cells.4 The active component of Mahonia aquifolium, berberine, has displayed antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties, which contribute to its efficacy in this disease process. The mainstay treatment of both inflammatory diseases involves the use of immunomodulatory therapy and corticosteroids.5,6 Due to the emerging trend of integrative medicine and the chronicity of each disease, many patients are inquiring about natural remedies to alleviate their symptoms. This makes it vital that dermatologists are aware of the efficacy and safety of topical botanical treatments readily available to patients.

One example of such an alternative medication native to the United States is M. aquifolium (Oregon grape, barberry, berberis) belonging to the Berberidaceae family. Plants of this family have been extensively used in traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment of various conditions such as periodontitis, dysentery, tuberculous, wounds, eczema, and icterus.7 M. aquifolium is one of the most abundant plants of the genus Mahonia and the most extensively studied in terms of its medicinal properties.7 The root and wood contain isoquinolone alkaloids including jatorrhizamine, palmatine, berberine, beramine, and magnoflorine, which account for its therapeutic use. Specifically, its antiinflammatory properties have led to its recent use in dermatologic disease.8 In a review, clinical trials on the use of M. aquifolium in cutaneous disorders were compiled to assess its efficacy and safety.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data search. We searched MEDLINE, PubMed, and the Web of Science for articles published from 1960 to October 2017. The following Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were used in MEDLINE: “ Mahonia aquifolium “ or “Oregon grape” or “berberis” and “skin,” with further search terms including “cutaneous,” “dermatology,” and “inflammatory disease.” In both PubMed and the Web of Science, equivalent search terms were used. In PubMed specifically, we were able to further filter the results to include clinical trials and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) as part of our inclusion criteria. Citations were reviewed in each relevant article to identify additional sources.

Criteria for inclusion and exclusion. Studies that were included evaluated the efficacy of M. aquifolium on cutaneous disorders. Specifically, we included RCTs and clinical trials with topical application of a single plant extract. Animal in vitro and in vivo studies were excluded as well as clinical trials with plant extract combinations. Articles were not excluded based on the primary language in which the article was written.

Risk of bias assessment. The Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool was used for the evaluation of the included RCTs. The tool assesses bias in seven domains including random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources of bias. In each of the domains, the risk of bias was determined as either low, unclear, or high in accordance with the judgment criteria.

RESULTS

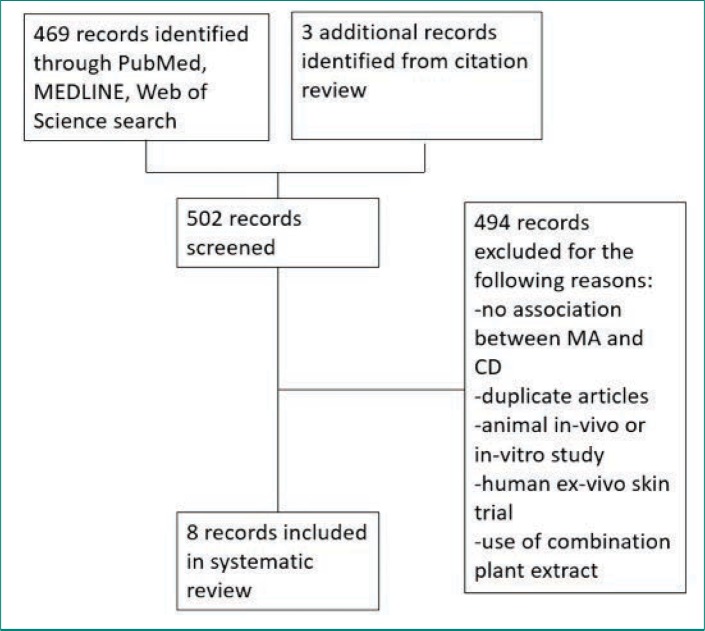

Of the 502 articles found, eight met the inclusion criteria, with seven studies evaluating the efficacy of M. aquifolium in psoriasis and one study evaluating the efficacy of such in atopic dermatitis (Figure 1). No other cutaneous disorders were identified in the literature review. In total, 910 participants were enrolled in the trials, with ages ranging from 16 years to 85 years. Outcome measures included the Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI), Eczema Area and Severity Index, semiquantitative immunohistochemistical analyses, and subjective ordinal scale reports based on symptomatic improvement. According to the Cochrane tool for assessing the risk of bias, six studies were determined to have unclear bias, while two studies had low bias. A summary of the study characteristics are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

FIGURE 1.

Study flow diagram. MA: Mahonia aquifolium; CD: cutaneous disease.

TABLE 1.

Sample characteristics of clinical trials examining the effects of Mahonia aquifolium on psoriasis patients

| TRIAL | MAHONIA AQUIFOLIUM TREATMENT GROUP (N) | CONTROL GROUP (N) | MEAN AGE (YEARS) | RECRUITMENT SOURCE | TREATMENT SITE | PATIENT STATUS AT BASELINE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gieler et al. (1995)9 | Baseline: n=433 Follow-up: n=375 |

Baseline: n=433 Follow-up: n=375 |

46 | 89 dermatologic practices in Germany | Upper extremities, lower extremities, and trunk | Mild to moderate, subacute or chronic psoriasis with maximum of 60 percent of body surface area affected without other chronic disorders |

| Bernstein et al. (2006)14 | Baseline: n=100 Follow-up: n=97 |

Baseline: n=100 Follow-up: n=74 |

48.3 | Six sites in the U.S. and Canada; recruited from private clinical practice, local college students, local newspapers advertisements, word of mouth | A 4.0 cm × 4.0 cm area of skin that typified the patient’s psoriasis, selected by investigator | In good overall health with mild to moderate plaque psoriasis covering less than 10 to 15 percent of body |

| Wiesenauer et al. (1996)10 | Baseline: n=82 Follow-up: n=80 |

Same individuals as the treatment group (placebo-controlled trial) | 48 | Twenty-two family physicians and dermatologists throughout Germany | All afflicted symmetrical areas on each half of the body | Clinically verified psoriasis vulgaris regardless of severity, older than 16 years of age, symmetric manifestation of lesions on both sides of body |

| Augustin et al. (1999)12 | Baseline: n=60 Follow-up: n=49 |

Same individuals as the treatment group (placebo-controlled trial) | Not reported | Not reported | All afflicted symmetrical areas on each half of the body | Psoriasis vulgaris diagnosis regardless of severity |

| Gulliver and Donsky (2005) | Baseline: n=39 Follow-up: n=24 |

Same individuals as the treatment group (placebo-controlled trial) | 45.5 | Board-certified dermatologist screened for eligible participants | All afflicted symmetrical areas on each half of the body | Mild to moderate chronic psoriasis with PASI<12 |

| Gulliver and Donsky (2005) | Baseline: n=32 Follow-up: n=30 |

Same individuals as the treatment group (placebo-controlled trial) | Not reported | Board-certified dermatologist screened for eligible participants | One site on each half of the body | Mild to moderate psoriasis with bilateral lesions on joints such as elbows or knees |

| Gulliver and Donsky (2005) | Baseline: n=33 Follow-up: n=33 |

Same individuals as the treatment group (placebo-controlled trial) | Not reported | Randomly assigned to Mahonia-treated group or standard treatment | All lesions on one side of the body | Mild to moderate psoriasis with bilateral lesions on joints such as elbows or knees |

| Donsky et al. (2007) | Baseline: n=42 Follow-up: n=30 |

Same individuals as the treatment group (placebo-controlled trial) | 54 | Recruited from clinical private practice, local colleges, local newspaper advertisements, by word of mouth; eligibility assessed via telephone screening | All lesions on skin | Adults with atopic dermatitis on 10 percent or less of body in overall good health |

TABLE 2.

Intervention characteristics of RCTs examining the effects of Mahonia aquifolium on psoriasis

| TRIAL | MAHONIA AQUIFOLIUM DELIVERY MODE | MODE OF PSORIASIS MEASUREMENT | FREQUENCY OF MEASUREMENT | LENGTH OF TREATMENT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gieler et al. (1995)9 | 10% M. aquifolium ointment in water-oil tincture based on anhydrous lanolin, wool wax alcohols, viscous paraffin, and vaselinum album | PASI scores | Weeks 2, 4, 8, 12 | 12 weeks with application 2 to 3 times daily |

| Bernstein et al. (2006)14 | Relieva (containing 10% proprietary M. aquifolium) cream | PASI scores | Weeks 4, 8, 12 | 12 weeks with application 2 times daily |

| Wiesenauer et al. (1996)10 | 10% M. aquifolium bark extract in ointment base containing anhydrous lanolin, paraffine, wool wax alcohols, cetylstearyl alcohol and white Vaseline | Three-ordinal rating scale based on patient and physician assessments | Week 4 | Total therapy length individually assigned by treating physician; average length: 4 weeks with application 2 to 3 times daily |

| Augustin et al. (1999)12 | 10% M. aquifolium ointment | Expression of ICAM-1, CD3, HLA-DR, keratin 6, keratin 16 | Week 4 | 4 weeks with application of M. aquifolium 3 times daily and dithranol once daily |

| Gulliver and Donsky (2005)13 | M. aquifolium cream with 0.1% berberine | PASI scores and DLQI | Weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12 | 12 weeks with application 2 times daily |

| Gulliver and Donsky (2005)13 | M. aquifolium cream with 0.1% berberine compared to calcipotriol and fluticasone proprionate | Patient response form based on subjective treatment response | Weeks 4, 12, and 6 months | 6 months with application once daily |

| Gulliver and Donsky (2005)13 | M. aquifolium cream with 0.1% berberine compared to calcipotriol and tazarotene | Scaling, thickness, and redness scored from 0–3 for each psoriatic plaque | Weeks 1, 2, 4 | 4 weeks with application once daily |

| Donsky et al. (2007)15 | Relieva (containing 10% proprietary M. aquifolium) cream | EASI scores and Subjective Reported Evaluation of Treatment form | Weeks 4, 8, 12 | 12 weeks with application 3 times daily |

| PASI: Psoriasis Area Severity Index; DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; EASI: Eczema Area and Severity Index | ||||

Efficacy of Mahonia aquifolium in psoriasis. In 1995, Gieler et al9 conducted an open-label, single-arm trial involving 89 dermatological centers consisting of 433 patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. After a 12-week treatment protocol with 10% M. aquifolium ointment, modified PASI scores were significantly declined from 5.5 at the entry to the study to 2.3 at the final examination (p <0.001). A symptomatic improvement was noted in 81.1 percent of patients as evaluated by dermatologists. Although 30 percent of patients were described as severely symptomatic at the start of the trial, only 5.6 percent of patients continued to have severe symptoms after 12 weeks. Burning and itching were reported as adverse side effects upon administration of the ointment; however, 82.4 percent of patients described the tolerability as good or very good.

In 1996, Wiesenauer et al10 conducted a double-blind, RCT comparing 10% M. aquifolium bark extract with an ointment base to a placebo ointment in 82 patients. Each patient served as his or her own control, as M. aquifolium ointment was applied to half of the body and the placebo ointment was applied to the other half for at least four weeks. Both patients and physician assessed improvement on a three-level ordinal scale consisting of no symptomatic improvement, symptomatic improvement, or complete disappearance of symptoms and both were unaware of which side contained the placebo or bark extract. Patients, but not physicians, reported a statistically significant improvement (p=0.008 in patient’s assessment; p=0.064 in physician’s assessment). Although more than half of patients and physicians noted no improvement, M. aquifolium was still considered superior to the placebo. Four patients experienced a cutaneous adverse drug reaction, which included either a burning or itching sensation or an allergic reaction.

In 1999, Augustin et al12 compared the effects of topical M. aquifolium ointment to dithranol ointment (a hydroxyanthrone proven effective in the treatment of psoriasis by inhibiting keratinocyte hyperproliferation and granulocyte function) on the expression of intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM) 1, cluster of differentiation (CD) 3, human leukocyte antigen—DR isotype (HLA-DR), and keratin 6 and 16 in a prospective, randomized half-side comparison study in which one cream was applied to one side of the body and the other cream to the other side.11 Forty-nine patients applied both creams daily and, at four weeks, skin biopsies were evaluated via immunohistochemistry to compare levels of immune markers. Both ointments led to a statistically significant reduction in relevant molecules as well as a reduction in epidermal and T-cell infiltration in comparison with preintervention samples. There was a greater reduction, however, in the dithranol-treated biopsies. Investigators deemed both ointments as effective treatments for psoriasis, though dithranol exhibited greater efficacy.

In 2005, Gulliver and Donsky13 reported three clinical trials using M. aquifolium 10% topical cream. The first was an open-label study that evaluated both the safety and efficacy of M aquifolium in 39 patients with chronic plaque psoriasis with application occurring three times daily over 12 weeks. Patients were evaluated at regular four-week intervals, and no adverse reactions were noted in the 19 patients who completed the full 12 weeks of therapy. Those who withdrew from the study did so primarily due to a lack of efficacy. In terms of efficacy, PASI score were used as an outcome measure, with a statistically significant improvement in PASI scores noted at each four-week appointment (p<0.001). The mean PASI score declined from 5.6 to 1.4 over the 12 weeks, and this improvement was stable one month after the discontinuation of therapy. There was no control group in this study, as efficacy of treatment was determined by the change in PASI score for each individual.

The other two studies were RCTs in which Mahonia cream was applied to half of the body, each with a different study design. One study consisted of 32 participants with mild to moderate psoriasis comparing M. aquifolium with 0.1% berberine (an active constituent of M. aquifolium predominantly responsible for its antipsoriatic effects) to a standard topical psoriasis treatment consisting of both calcipotriol and fluticasone proprionate. Symptoms were evaluated at each visit at four weeks, eight weeks, and six months. Of the total patient cohort, 84 percent rated the Mahonia cream as having a good to excellent response, 6.7 percent rated it as having a minimal response and 10 percent reported no response. Furthermore, 63.3 percent of patients reported the M. aquifolium as equal to or better than the standard treatment received, while 37 percent rated the cream as inferior to the standard. No adverse events were reported by patients.13

The second RCT consisted of 33 patients also with mild to moderate psoriasis, but in this trial, the standard psoriasis treatment used for comparison was calcipotriol and tazarotene gel. A photographic assessment was done at each visit at Weeks 1, 2, and 4. Scaling was the first symptom to improve with M. aquifolium and some patients showed a response by the first week of use. The thickness of psoriatic plaques tended to decline during Weeks 2 through 4 and erythema improved gradually. In all 33 patients, the Mahonia cream was equal to or better than the standard treatment with no adverse side effects reported. In both of these studies, no results concerning statistical significance were reported. As observational studies, the authors did not design the studies to produce data for statistical anlysis.13

In 2006, Bernstein et al14 completed a double-blind, placebo-controlled study involving 200 patients with mild to moderate psoriasis using either topical Reliéva cream (homeopathic product containing 10% psoberine, a proprietary M. aquifolium extract by Apollo Pharmaceutical in a patented liposome preparation and formulated in an emulsion cream base) or placebo twice daily for 12 weeks. Quality of Life Index (QLI) and PASI questionnaires were used to assess safety and efficacy respectively. One hundred seventy-one patients completed the study. Lack of efficacy was the primary reason for withdrawal, which occurred in two patients in the active group and 11 in the placebo group. Mahonia-treated patients showed a statistically significant improvement in both measures. Specifically, mean PASI scores declined from 6.93 to 3.35 (p=0.0095) and QLI decreased by an average score of 25.5 (p=0.0186). Less than one percent of patients experienced side effects including a burning sensation or rash. Investigators determined the plant extract as both effective and safe to use in mild to moderate psoriasis.14

Efficacy of Mahonia aquifolium in atopic dermatitis. In 2007, Donsky et al15 conducted an open-label RCT with 42 adult patients diagnosed with atopic dermatitis. After 12 weeks of treatment with the application of Reliéva three times daily, the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) and Subject Reported Evaluation of Treatment survey consisting of treatment options as “much worse,” “worse,” “better,” and “much better” were completed. EASI scores decreased by 75, 91, and 97 percent after four, eight, and 12 weeks of treatment, respectively (p<0.0001). Specifically, EASI scores significantly declined from a mean of 2.01 to 0.06 at the end of 12 weeks. As compared with no treatment, the efficacy of treatment, extent of pruritus, and appearance of the rash was perceived as “better” or “much better” in 93, 83.4, and 93.3 percent of patients, respectively. One patient reported “worse” in his response to all of the questions, while no patient indicated that their symptoms were “much worse.” Four patients reported side effects including pruritus and burning sensation. Of the 42 patients enrolled in the study, eight patients dropped out of the study right after their baseline visit, three after the four-week follow-up visit, and one after the eight-week follow-up visit. The investigators concluded that Reliéva cream is a safe and effective treatment of atopic dermatitis in adult patients.15

DISCUSSION

Summary of included studies. Of the seven studies identified as evaluating the safety and efficacy of M. aquifolium, five reported a statistically significant improvement in symptom severity, two studies were observational and their results were not designed to report statistical significance, and one study showed that patients but not physicians reported a statistically significant improvement in symptoms. Likewise, in the evaluation of its use in atopic dermatitis, only one study was conducted based on our literature search, which showed a statistically significant improvement in EASI score (p<0.0001). Various outcome measures were reported by each study; however, three studies evaluated the efficacy in psoriasis using PASI scores. In these studies, either 10% M. aquifolium cream or ointment was applied over 12 weeks, resulting in a statistically significant decline in mean PASI score. Gieler et al,9 Gulliver et al,13 and Bernstein et al14 reported a decline of of 3.2 (p<0.001), 4.2 (p<0.001), and 3.58 (p=0.0095), respectively. It is difficult to determine whether an ointment or a cream vehicle is more effective in delivering M. aquifolium given that similar PASI reduction scores were found among the studies with each vehicle type. Each of these three studies also had similar mean PASI scores at the initiation of treatment corresponding to mild to moderate disease severity. Further studies would be indicated to determine efficacy in severe psoriatic patients.

In terms of comparative studies, Augustin et al12 found that the standard treatment of dithranol is more efficacious than M. aquifolium at decreasing certain inflammatory markers including ICAM-1, CD-3, HLA-DR, and keratin 6 and 16. Donsky and Gulliver13 compared M. aquifolium to the standard treatments of calcipotriol with fluticasone proprionate as well as calcipotriol with tazarotene. The authors report that M. aquifolium had a subjective response equal to or better than the standard treatment in 63 percent of patients and 100 percent of patients, respectively.

Mechanism of action of Mahonia aquifolium. The medicinal effect of M aquifolium has been primarily attributed to berberine, one of the alkaloids present in the plant extract. Many mechanisms have been described to contribute to its anti-inflammatory role. The extract has been shown to markedly inhibit 5-lipoxygenase and lipid peroxidation in liposomes.16,17 Augustin et al12 demonstrated a similar reduction in immune markers, specifically, ICAM-1, CD-3, HLA-DR, and keratins 6 and 16. The same study revealed a decline in T-cell infiltration in exposed psoriatic lesions.11 Berberine-treated cells also showed a decline in cyclooxygenase activity with a subsequent reduction in prostaglandin E2. In an oral cancer cell line, berberine was applied every 12 hours, leading to a rapid reduction in cyclooxygenase protein within three hours. Prostaglandin E2 declined in a dose-dependent manner.18 Recently, cytokine inhibition of IL-8 by berberine also was identified as another mechanism for its anti-inflammatory role.19

The extract has additionally been shown to have an antiproliferative effect on human keratinocytes. Berberine itself exhibits an inhibition of cell growth to about the same extent as the extract itself, which is suggestive of a dominant role in the mechanism of action.8 Cell growth is inhibited via the intercalation of berberine into DNA with subsequent prevention of DNA replication and cellular proliferation.20 Keratinocyte proliferative markers are also decreased with treatment.12 Other alkaloids in M. aquifolium including oxyberberine, corytuberine, columbamine, and jatrorrhizine have also been shown to inhibit lipoxygenase, contributing to its anti-inflammatory role in psoriasis.17

Dosage for topical application. No study has been done to evaluate the efficacy and safety at various topical dosages. All but one of the above trials used 10% M. aquifolium cream or ointment, which has been shown to have effect on inflammatory conditions with minimal side effects. Further studies are indicated to determine which vehicle is most efficacious. No safe or effective dose has been determined in children; therefore, use in children is not recommended. No studies have been done to assess the efficacy of oral formulations; hence, it is not recommended as a treatment option.

Potential role in treatment of acne vulgaris. As part of traditional Chinese medicine, M. aquifolium has been used for the treatment of acne. Although no clinical trials have been conducted for this indication to date, there is evidence to suggest that it might play a beneficial role. In 2004, Slobodníková et al21 tested M. aquifolium as well as isolated concentrations of alkaloids naturally present in the plant. Berberine, jatorrhizine, and crude M. aquifolium showed the strongest activity against 20 strains of Propionibacterium acnes isolated from skin lesions in patients with severe acne. Minimum inhibitory concentrations ranged from 5µg/mL to 50µg/mL.21 In an in-vivo animal trial, Seki et al22 also demonstrated that lipogenesis is suppressed by berberine in sebaceous glands by 63 percent, also supporting its potential use as an alternative treatment of acne. Further studies in clinical trials would be beneficial to determine the efficacy of treating this cutaneous disorder.

LIMITATIONS

In the clinical trials evaluating the use in psoriasis, the main reason for patients failing to adhere to follow-up and, therefore, become excluded from the final data analysis was the lack of efficacy of the medication. This indicates that true efficacy, based on reported symptomatic improvement, might be overestimated by investigators. The trials had inconsistencies in study methodology including frequency of application, dosage, length of treatment, and method of objective analysis, making it difficult to compare data among trials. Data might also have been influenced by not eliminating confounding factors such as sunlight, which has been shown to improve plaque psoriasis.23

Although deemed efficacious in the treatment of atopic dermatitis, additional clinical studies would be beneficial to confirm the effects in this cutaneous disorder. A single trial has been reported, which had a limited sample size (n=42), and 28 percent of its participants failed to complete the study in its entirety. Further studies that compare the medication to a standard topical treatment in atopic dermatitis would be beneficial as well. Children were also not included in any trial, limiting the extrapolation of data to this patient population.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on the clinical trials performed to date, M. aquifolium has shown the ability to prompt a statistically significant improvement in symptoms of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis and was deemed a safe and effective therapeutic option in such studies. Side effects were minimal and well-tolerated, limited to pruritus, rash, or burning sensation. There are extensive amounts of data supporting its use and efficacy in psoriasis. Gulliver et al determined M. aquifolium was equal to or better than calcipotriol and tazarotene gel in all 33 patients. Likewise, a second study showed that 63 percent of patients considered Mahonia cream to be equal to or better than the standard of calcipotriol and fluticasone propionate.13 The extract was effective at reducing immune markers as compared with dithranol, but the latter was considered more potent.12 One study showed a statistically significant improvement in the severity of atopic dermatitis when compared to placebo treatment. Further studies are indicated to determine the appropriate dose, vehicle, and treatment duration in each disease process.

REFERENCES

- 1.Griffiths C, Kerkhof P, Czernacka-Operacz M. Psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7(1):31–41. doi: 10.1007/s13555-016-0167-9. Suppl. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2016;387:1109–1122. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00149-X. 10023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogawa E, Sato Y, Minagawa A et al. Pathogenesis of psoriasis and development of treatment. J Dermatol. 2018;45(3):264–272. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guttman-Yassky E, Waldman A, Ahluwalia J. Atopic Dermatitis: pathogenesis. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2017;36(3):100–103. doi: 10.12788/j.sder.2017.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ring J, Alomar A, Bieber T et al. Guidelines for Treatment of Atopic Eczema (Atopic Dermatitis) Part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(8):1045–1060. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nast A, Jacobs A, Rosumeck S et al. Efficacy and safety of systemic long-term treatments for moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(11):2641–2648. doi: 10.1038/jid.2015.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He J, Qing M. The medicinal uses of the genus Mahonia in traditional Chinese medicine: An ethnopharmacological, phytochemical and pharmacological review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;175:668–683. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mueller K, Ziereis K, Gawlik I. The antipsoriatic Mahonia aquifolium and its active constituents; II. Antiproliferative activity against cell growth of human keratinocytes. Planta Med. 1995;61(1):74–75. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-958005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gieler U, A von der W, Heger M. Mahonia aquifolium: a new type of topical treatment for psoriasis. J Dermatol Treat. 1995;6(1):31–34. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiesenauer M, Lüdtk R. Mahonia aquifolium in patients with psoriasis vulgaris—an Intraindividual Study. Phytomedicine. 1996;3(3):231–235. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(96)80058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kemeny L, Ruzicka T, Braun-Falco O. Dithranol: a review of the mechanism of action in the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. Skin Pharmacol. 1990;3(1):1–20. doi: 10.1159/000210836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Augustin M, Andrees U, Grimme H et al. Effects of Mahonia aquifolium ointment on the expression of adhesion, proliferation, and activation markers in the skin of patients with psoriasis. Forsch Komplementarmed. 1999;6(2):19–21. doi: 10.1159/000057142. Suppl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gulliver W, Donsky HJ. A report on three recent clinical trials using Mahonia aquifolium 10% topical cream and a review of the worldwide clinical experience with Mahonia aquifolium for the treatment of plaque psoriasis. Am J Ther. 2005;12(5):398–406. doi: 10.1097/01.mjt.0000174350.82270.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernstein S, Donsky H, Gulliver W et al. Treatment of mild to moderate psoriasis with Reliéva, a Mahonia aquifolium extract—a double-blind, placebocontrolled study. Am J Ther. 2006;13(2):121–126. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200603000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donsky H, Clarke D. Reliéva, a Mahonia aquifolium extract for the treatment of adult patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J Ther. 2007;14(5):442–446. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e31814002c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muller K., Ziereis K. The antipsoriatic Mahonia aquifolium and its active constituents; I. Proand antioxidant properties and inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase. Planta Med. 1994;60(5):421–424. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-959523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Misik V, Bezakova L, Malekova L et al. Lipoxygenase inhibition and antioxidant properties of protoberberine and aporphine alkaloids isolated from Mahonia aquifolium. Planta Med. 1995;61(4):372–373. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-958107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuo CL, Chi CW, Liu TY. The anti-inflammatory potential of berberine in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Lett. 2004;203(2):127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hajnická V, Kostalova D, Svecova D et al. Effect of Mahonia aquifolium active compounds on interleukin-8 production in the human monocytic cell line THP-1. Planta Med. 2002;68(3):266–268. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-23126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmeller T, Latz-Bruning B, Wink M. Biochemical activities of berberine, palmatine and sanguinarine mediating chemical defence against microorganisms and herbivores. Phytochemistry. 1997;44(2):257–266. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(96)00545-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slobodníková L, Kostalova D, Labudova D et al. Antimicrobial activity of Mahonia aquifolium crude extract and its major isolated alkaloids. Phytother Res. 2004;18(8):674–676. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seki T, Masaaki M. Effect of some alkaloids, flavonoids and triterpenoids, contents of Japanese- Chinese traditional herbal medicines, on the lipogenesis of sebaceous glands. Skin Pharmacol. 1993;6(1):56–60. doi: 10.1159/000211087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paul C, Gallini A, Archier E et al. Evidence-based recommendations on topical treatment and phototherapy of psoriasis: systematic review and expert opinion of a panel of dermatologists. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(3):1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04518.x. Suppl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]