Abstract

Background

Armed conflicts affect more than one in 10 children globally. While there is a large literature on mental health, the effects of armed conflict on children’s physical health and development are not well understood. This systematic review summarizes the current and past knowledge on the effects of armed conflict on child health and development.

Methods

A systematic review was performed with searches in major and regional databases for papers published 1 January 1945 to 25 April 2017. Included studies provided data on physical and/or developmental outcomes associated with armed conflict in children under 18 years. Data were extracted on health outcomes, displacement, social isolation, experience of violence, orphan status, and access to basic needs. The review is registered with PROSPERO: CRD42017036425.

Findings

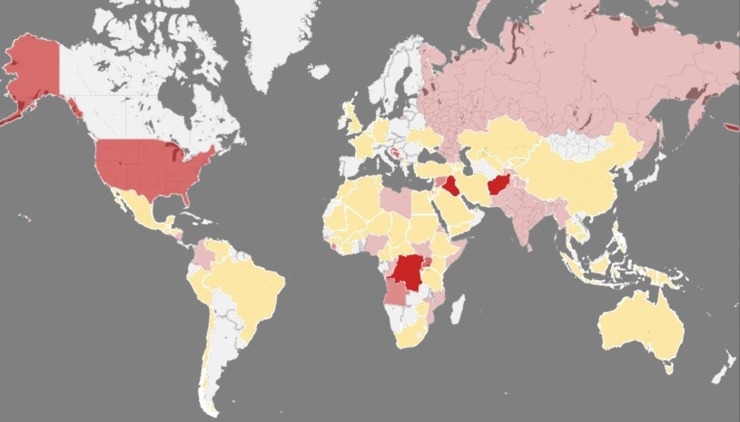

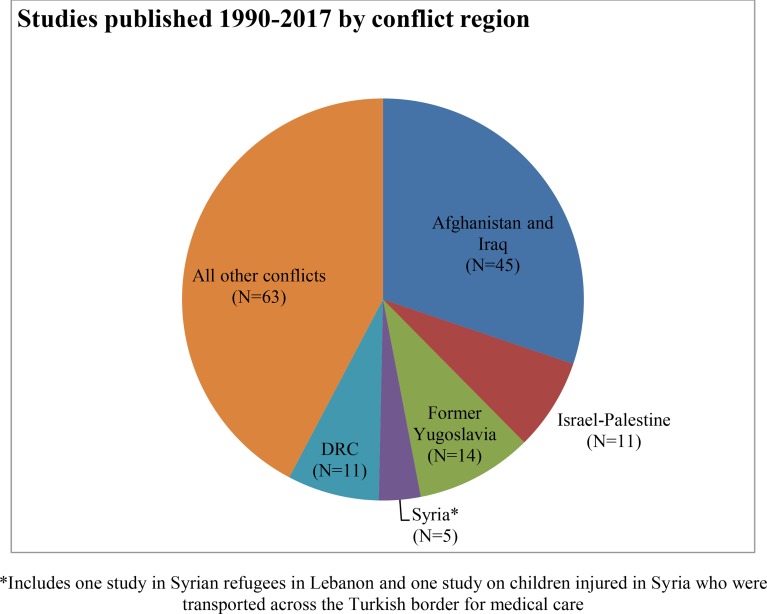

Among 17,679 publications screened, 155 were eligible for inclusion. Nearly half of the 131 quantitative studies were case reports, chart or registry reviews, and one-third were cross-sectional studies. Additionally, 18 qualitative and 6 mixed-methods studies were included. The papers describe mortality, injuries, illnesses, environmental exposures, limitations in access to health care and education, and the experience of violence, including torture and sexual violence. Studies also described conflict-related social changes affecting child health. The geographical coverage of the literature is limited. Data on the effects of conflict on child development are scarce.

Interpretation

The available data document the pervasive effect of conflict as a form of violence against children and a negative social determinant of child health. There is an urgent need for research on the mechanisms by which conflict affects child health and development and the relationship between physical health, mental health, and social conditions. Particular priority should be given to studies on child development, the long term effects of exposure to conflict, and protective and mitigating factors against the harmful effects of armed conflict on children.

Introduction

Millions of children are thought to be impacted by armed conflict worldwide, with estimates for the number of children living in areas affected by conflicts ranging as high as 246 million.[1] Over the past several decades schools, health facilities, and health workers have become direct targets, increasing the impact of war on children.[2, 3] Of the 49 armed conflicts that occurred in 2016, 12 were wars (Fig 1).[4, 5]

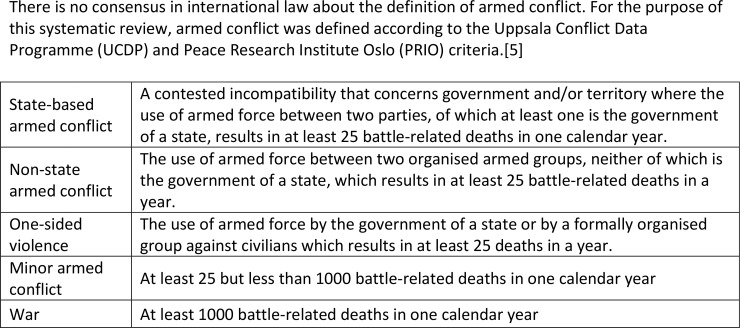

Fig 1. Definitions of armed conflict and conflict intensity.

Children who are exposed either directly or indirectly to armed conflict suffer harm that persists across their life course and beyond, to subsequent generations born after the conflict has ended. Although this impact has been anecdotally chronicled in news reports and literature, there is limited medical and public health research on how conflict affects on child physical health and development. Even the number of children directly or indirectly affected by conflict remains unclear.

The direct effects of combat on child health may include injury, illness, psychological trauma, and death. A complex set of political, social, economic, and environmental factors resulting from conflicts have indirect and lasting effects on children. Inadequate living conditions, environmental hazards, such as damaged buildings and unexploded ordnance, and lack of access to safe water and sanitation place children at risk for preventable and treatable diseases and injuries. The destruction of medical and public health infrastructure make it difficult to treat affected children by limiting both access and quality of available care.

Conflicts force children and families to leave their homes to seek safety within national borders (internal displacement) and across international borders—nearly two-thirds of the 28 million forcibly displaced children are internally displaced.[6] During flight, children may become separated from their families and are more vulnerable to infections, psychological trauma, and exploitation.[7, 8] Experiences of trauma affect children’s mental health, as well as that of their caregivers. Poor mental health of caregivers may negatively affect children’s physical and mental health, as well as their educational attainment and life opportunities.[8, 9] The destruction of educational and economic infrastructure creates conditions of poverty, which may last for generations. Economic and political sanctions deepen this poverty and have detrimental effects on child health and nutrition.[10]

Little is known about the impact of armed conflict on children’s physical health and development—even estimates of the number of children killed by conflict are lacking.[11–14] Research has focused primarily on the mental health effects of armed conflict on children and on downstream effects such as displacement.[9, 15–20] We undertook a systematic review of the evidence of the impact of armed conflict on children’s physical health and child development. Where available, risk factors, mitigating factors, and protective factors were abstracted.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

Searches were undertaken in PubMed, Web of Science, CINAHL, EMBASE, Latin American and Caribbean Health Science (LILACS), IndMED, Africa-Wide Information, Open Grey and the New York Academy of Medicine Grey Literature Report from 1 January 1945 to the search date. The initial searches were performed 8–12 June 2015. The PubMed and EMBASE searches were updated on the 24 and 25 April 2017, respectively. The review is registered with PROSPERO: CRD42017036425.

Our intention was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of available data on the physical health and developmental effects of armed conflict on children. During the searches, it became clear that the varied focus, heterogeneous design, and variation in reporting of outcomes by published studies would not support this type of review. The aim of our review was therefore shifted to describe published studies on the effects of armed conflict on child health and development.

Search terms included multiple variants of “child” and “war.” Terms for physical health and child development were not used, as inclusion of these terms narrowed the search results and missed relevant papers known to the authors. The search terms used are provided in the web appendix. Medical Subject Headings terms were used when available, and snowball and hand searching was used to identify additional studies.

Screening and full text review was conducted by Ayesha Kadir (AK) and Sherry Shenoda (SS) for all publications using Covidence,[21] an electronic organisational tool for systematic reviews. Inclusion criteria included study population, setting of past or current armed conflict or a region where refugees/asylum-seekers are staying, and exposure of the study population to armed conflict. Armed conflict was defined according to the Uppsala Conflict Data Programme (UCDP)/Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) criteria (Fig 1).[5] The UCDP database was used to identify conflicts meeting criteria for inclusion.[22] We included original research studies that provided data on children ages 0–18 years. Outcomes included physical or developmental morbidity associated with exposure to armed conflict, exposure to violence, and access to basic needs, including health care and education. Studies on mental and behavioural health were excluded unless they also provided data on physical health or child development. Additional exclusion criteria included review papers, studies published prior to 1945, and studies with a median date of data collection earlier than 1940. Studies on terrorism were excluded, as terrorist incidents are not universally associated with armed conflict. The Palestinian-Israeli conflict was considered to be an armed conflict. Studies providing data exclusively on nutrition, perinatal mortality, birth weight, breast and infant feeding, and immunization coverage were excluded; while the evidence remains limited on the scale and nature of the impact of armed conflict on these indicators, child nutrition and maternal and newborn health are broadly recognised as carrying high risk in conflict settings.[23, 24] However, if these data were presented together with other child health and development outcomes, then data for all reported child health and development outcomes were extracted. Studies on the effects of exposure to the atomic bomb were excluded, as there are existing reviews on this subject. Post war studies were included if they provided associations of the outcomes with armed conflict. No restrictions were made for sex, geographic location, language, or study design.

The risk of bias was assessed at the study ad outcome levels for each individual study based on the data source, study population, sampling strategy, data collection and analysis methods, and any special characteristics of the population. Studies that were deemed to have unsound or invalid methods were excluded. Given the challenges in obtaining data in conflict settings, studies from single facilities, studies using only facility-based data, and case reports were included. Data from studies meeting inclusion criteria were abstracted onto a data extraction form, including time period, study country and sub-region, identified conflict, study design, reference population, type of exposure, health outcomes, access to basic needs, mortality, and associations between exposures and outcomes. Where available, data were abstracted for protective and mitigating factors on child health outcomes. When possible, authors were contacted for missing data. In the case of queries or differences, an agreement was negotiated between the reviewers.

Role of the funding source

The University of Florida-Jacksonville provided partial funding for the study. There was no additional external funding received for this study. The study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, and writing of the report were undertaken independently. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and they shared responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

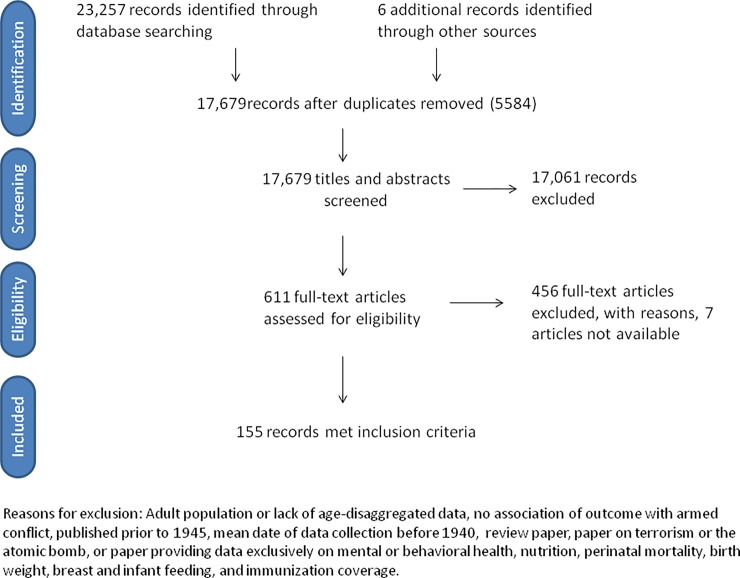

The searches retrieved 23,257 records, and six additional papers were retrieved through snowball and hand searching. After removal of duplicates, 17,679 titles and abstracts were screened. Of 618 papers eligible for full-text review, 7 were not available. 611 papers were reviewed in full text. 456 studies were excluded, with reasons (Fig 2). Our final sample consisted of 155 studies, including 18 published between July 2015 and April 2017.

Fig 2. Flow diagram.

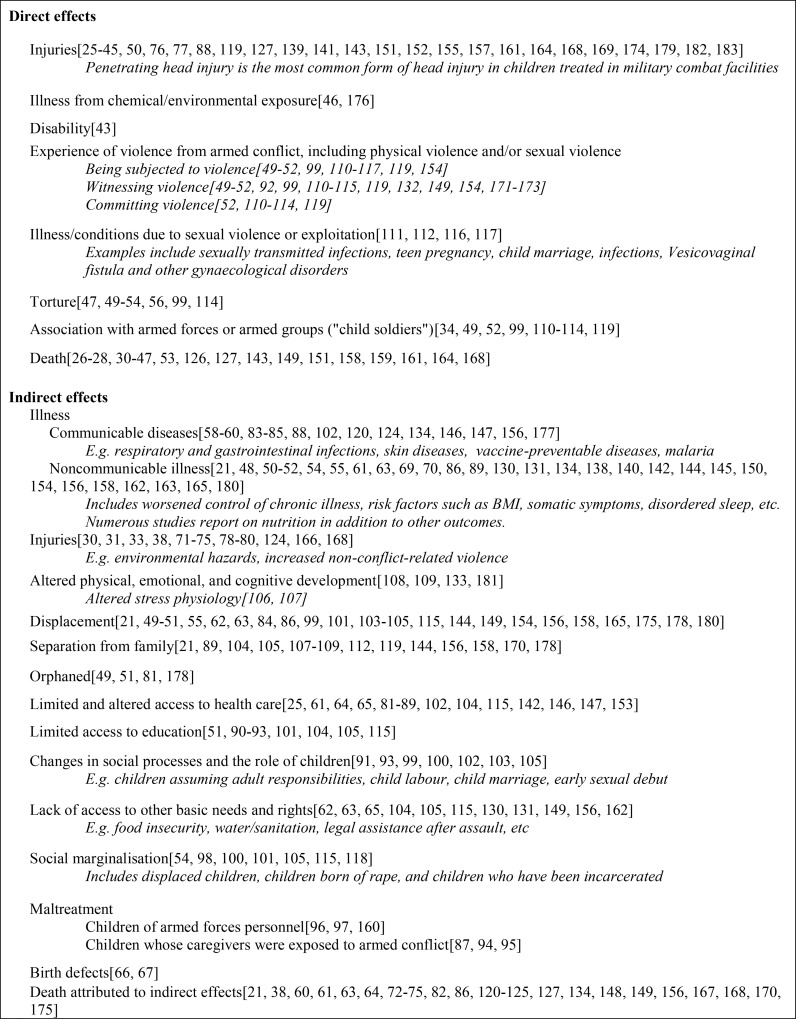

Among the included publications, 131 were quantitative studies, 18 qualitative, and six were mixed methods design. Included in the quantitative studies were 20 case reports, 44 chart or registry reviews, and 48 cross-sectional studies. The data from these studies is too heterogeneous to be pooled for meta-analysis. Collectively, they provide a body map of the child affected by armed conflict (Table 1 and Fig 3).

Table 1. Summary of included studies.

| Studies published 1 January 1945–12 June 2015 | |||||

| Autdor | Conflict zone | Population | Sample size | Summary of findings | |

| 1 | Aaby et al,[21] 1999 | Guinea Bissau | IDP and resident children | 422 | During the period of displacement, child mortality increased and nutritional status deteriorated for both IDP children from Bissau and resident children. Mortality for resident children was 4.5 times higher, decline in growth was significantly worse, and recovery later than for displaced children. |

| 2 | Abushaban et al,[66] 2004 | Kuwait | Kuwaiti infants with CHD | 2,256 | 2,256 babies with congenital heart disease (CDH). The mean annual incidence of CHD rose from 39.5 per 10 000 live births pre-war (1986–1989) to 103.4 per 10 000 live births post war (1992–2000) |

| 3 | Amitai et al,[138] 1992 | Israel-Palestine | Emergency department cases | 268 | Accidental atropine poisoning in children from atropine autoinjector provided to families in case of organophosphate nerve gas attacks. |

| 4 | Araneta et al,[67] 2003 | Iraq | Infants born to US military personnel who served in February 1991 | 45,013 | Increased prevalence of congenital disorders in infants conceived post-war to Gulf War veterans (GWV). Infants of GWV men had increased rate of tricuspid insufficiency or regurgitation, aortic stenosis, and renal agenesis or hypoplasia. Infants of female GWVs had higher prevalence of hypospadias. |

| 5 | Ascherio et al,[60] 1992 | Iraq | National | 16,076 | Three-fold increase in infant and child mortality after start of conflict. Four-fold and five-fold increases in age-adjusted mortality from injuries and diarrhoea, respectively. Regional differences in child mortality were maintained or exacerbated after onset of conflict. |

| 6 | Avogo and Agadjanian,[86] 2010 | Angola | Migrants to Luanda | 719 | Increased mortality among children whose families were displaced due to war. This effect was strongest during the first year after migration. |

| 7 | Barisić et al,[139] 1999 | Former Yugoslavia | Children with nerve injuries | 27 | Peripheral nerve injuries in children due to war involved multiple nerves, were located proximally on upper extremities, had complete or severe nerve damage, delayed reinnervation and poor spontaneous recovery outcomes. These patterns differed from children with peripheral nerve injury due to accidents, who primarily had single, partial peripheral nerve injuries that were located on distal extremities. |

| 8 | Barnes et al,[140] 2007 | Iraq | US high school students | 121 | Children of deployed military personnel had significantly higher BMI than non-deployed and civilian counterparts. Children of both deployed- and non-deployed military personnel had a higher mean HR than children of civilians. |

| 9 | Bertani et al,[141] 2015 | Afghanistan | Patients <16 years in a NATO military combat hospital | 89 | Injuries due to explosive device were more common in children than from firearms and were associated with a high rate of both traumatic and surgical amputation. All fractures were open fractures, with high rates of vessel and nerve injuries. |

| 10 | Betancourt et al,[111] 2008 | Sierra Leone | Former child soldiers | 260 | Child soldiers describe witnessing violence, becoming soldiers for survival, child labour, sexual violence, and unwanted pregnancy. |

| 11 | Betancourt et al,[110] 2010 | Sierra Leone | Former child soldiers | 156 | Average abduction age 10.5 years, nearly all were forced into conscription, nearly all reported witnessing violence, more than 1/4 had killed someone (including a loved one) and 1/3 of girls reported being raped |

| 12 | Bilukha and Brennan,[71] 2005 | Afghanistan | Injuries due to landmine or UXO | 6,114 | UN database, 1997–2002. 54% of UXO injuries were in children, the majority between ages 5–14 years. Of these, 42% were injured while playing with the device” |

| 13 | Bilukha et al,[73] 2003 | Afghanistan | Injuries due to landmine or UXO | 1,636 | ICRC database 2001–2002: 46% of UXO injuries were in children under 16 years. 49% of children injured were playing or tending animals. |

| 14 | Bilukha et al,[75] 2006 | Chechnya | Civilian injuries due to landmine or UXO | 3,021 | Region wide data, 1994–2005. 26% of UXO injuries were in children under 18 years, with 17% mortality rate in these children. 35% of children with upper body injuries, 20% with lower body injury, 24% with both upper and lower body injury, and 26% had limb amputations. |

| 15 | Bilukha et al,[72] 2008 | Afghanistan | Injuries due to landmine or UXO | 5,471 | ICRC database, 2002–2006. 47% of injuries and deaths were in children. 42% of child UXO injuries were upper body and 27% were both upper and lower body injuries. 2/3 of child injuries occurred during active hostilities. 2/3 were in children tending animals or tampering or playing with an explosive device |

| 16 | Bilukha et al,[74] 2011 | Nepal | Injuries due to landmine or UXO | 307 | National prospective surveillance 2006–2010. 55% of injuries were in children under 18 years, with 15% mortality rate in these children. Nearly two-thirds of child injuries occurred while playing or tampering with an explosive device, the greatest number in children aged 10–14 years old. 40% of explosions occurred in victim's homes. |

| 17 | Bodalal et al,[142] 2014 | Libya | Deliveries at a single health facility | 13,031 | Prevalence of preterm deliveries and LBW increased during the conflict when compared with pre-war. There was a higher rate of caesarean section delivery and episiotomy during the conflict. |

| 18 | Bogdanovich and Schevchenko,[25] 1946 | WWII | Paediatric eye injuries at a single tertiary facility | 220 | Incidence of ocular trauma increased 3.2 during armed conflict compared with peacetime. 84% of cases were in school-aged children.85% injuries were from weapons of war. Half of children presented 6 days or later after injury. |

| 19 | Borgman et al,[41] 2012 | Afghanistan and Iraq | Paediatric patients treated at US military combat facilities | 7,505 | Data from Patient Administration Systems and Biostatistics Activity Database (PASBA) and Joint Theatre Trauma Registry (JTTR). 79% of paediatric admissions were due to trauma. Paediatric trauma patients had higher mortality and longer hospital stays than adult comparison groups. Most common Injury mechanisms were blast, penetrating, blunt trauma, and burns. Children under <8 years had higher mortality than children >8 years. |

| 20 | Borgman et al,[143] 2015 | Afghanistan and Iraq | Isolated burn patients treated in US military combat facilities | 4,743 | Paediatric burns patients in conflict zones have higher mortality compared with patients in the United States. |

| 21 | Bosnjak et al,[89] 2002 | Former Yugoslavia | Children with seizures in two facilities | 111 | Displaced children from war-affected areas had worsened epilepsy control, with greater frequency of epileptic seizures and less regular follow up. These children were also more likely to be separated from their fathers or both parents than children from areas not directly affected by the war. Medication compliance was similar in both groups. |

| 22 | Bronstein and Montgomery,[144] 2013 | Afghanistan | Unaccompanied minors in state care in London | 222 | Nearly 2/3 of children reported sleep disturbance in the form of nightmares |

| 23 | Busby et al,[145] 2010 | Iraq | Households in Fallujah | 711 | Risk ratio 12.6 for childhood cancer in children in Fallujah 0–14 years compared with peers in Egypt and Jordan. |

| 24 | Celikel et al,[26] 2015 | Syria | Syrian children injured due to war in Syria who died in a single Turkish facility | 140 | 18% of in-hospital deaths were children, median age was 12. 70% of injuries were from bombing and shrapnel, 13.6% gunshot wounds, 13.6% blunt force and 2.8% motor vehicle crashes while trying to escape. 2/3 of paediatric deaths were due to head injuries, and 30% had isolated head and neck injuries |

| 25 | Chironna et al,[146] 2001 | Kosovo | Kosovar refugee children and youth in camps in Italy | 371 | 251 children ≤10 years, 119 were 11–20 years. Hyperendemic Hepatitis with exposure in early childhood. 61% of children aged 2–1 0 years were seropositive and 100% of children over 11 years were HAV seropositive. 11% of children 2–10 years were HBV positive and 39% of children and youth aged 11–20 were HBV positive. No children had been vaccinated against HBV. |

| 26 | Chironna et al,[147] 2003 | Iraq and Turkey | Kurdish refugee children and youth in camps in Italy | 269 | 98 children ≤10 years, 171 were 11–20 years. Hyperendemic Hepatitis A, High seroprevalence of Hepatitis E, with 89% of Hepatitis E exposed from Iraq. Hepatitis B was also endemic, and children from both Turkey and Iraq had low vaccination rates against Hepatitis B. |

| 27 | Cliff et al,[130] 1997 | Mozambique | Children in Mogincual district, Mozambique | 228 | High rates of malnutrition in war-affected areas, with a two-year outbreak of clinical Konzo. Konzo was attributed to shortened cassava processing due to war-related disruption |

| 28 | Cohn et al,[48] 1979 | Chile | Chilean refugee children in Denmark | 75 | All children were either tortured, had a parent who was tortured, or had a parent who was imprisoned in Chile. One third of children had sleep disturbances including nightmares and difficulty falling asleep. 1/4 reported nocturnal enuresis. Numerous somatic complaints, including anorexia, headaches, abdominal pain, difficulty concentrating, impaired memory, and constipation. |

| 29 | Coppola et al,[27] 2006 | Iraq | Paediatric cases treated at a US military combat facility | 85 | Data from surgical logs. Patterns of trauma included fragmentation wound (52%), penetrating trauma (23%), burn (19%), and blunt trauma (6%). The primary injury site was the lower extremities in 38%, followed by head injury (23%). |

| 30 | Cowan et al,[68] 1997 | Iraq | Live births to military service members | 75,461 | No elevated risk of birth defects, reduced fertility or differences in sex ratio was found among veterans of the first Gulf War. |

| 31 | Creamer et al,[28] 2009 | Afghanistan and Iraq | Paediatric patients treated in US military combat facilities | 2,060 | Data from PASBA database. Children accounted for a tenth of all combat support hospital admissions, the majority of which suffered penetrating trauma. Gunshot wounds were more common in Iraq, while burns and landmine injuries were more common in Afghanistan. Younger age was associated with higher mortality. |

| 32 | Curlin et al,[120] 1976 | Bangladesh | Population in Matlab Bazaar, Bangladesh | 120,000 | During the war, overall infant mortality rate rose 15% above baseline, of which the post-neonatal infant mortality rose 46%. Mortality in 1–4 year olds rose 43%. Mortality for all U5 subgroups returned to baseline during the year after the war. Among children 5–9 years olds, mortality rose 208% during the war and continued to rise during the year after, to 281% above baseline, attributed to smallpox and dysentery epidemics. |

| 33 | de Smedt,[103] 1998 | Rwanda | Rwandan refugees in Tanzania | 6 | Describes complex changes in social norms after the displacement due to conflict. Child marriage became common, with the median age of girls 15 years, and 15 years for boys. Marriages were reported in girls as young as 13 and boys as young as 14. |

| 34 | Deeb et al,[148] 1997 | Lebanon | Children in Beirut | 4101 | Muslim children had 1.6 times the risk of dying before 5 years compared to Christians. When controlling for the number of children ever born to the mothers, elevated risk of U5 mortality remained significant for lowest social class of Muslims only. |

| 35 | Denov,[112] 2010 | Sierra Leone | Former child soldiers | 80 | Describes children’s involvement with armed groups in detail. Children acted as front-line combatants, commanders of other child soldiers, spies, porters, cooks, domestic servants, and care-takers of younger children. The children described being subjected to extreme physical, psychological, and sexual violence, as well as injuries, chronic pain, loss of family and social and economic marginalisation. |

| 36 | Depoortere et al,[149] 2004 | Darfur, Sudan | IDPs in Darfur | 17,339 | In two villages affected by armed conflict, 5% and 34.5% of violent deaths were in children under 15. One refugee camp had markedly elevated non-violent mortality, of which 48% of deaths were in children under 5 years |

| 37 | Devanarayana and Rajindrajith,[150] 2010 | Sri Lanka | Children in two schools in war affected regions | 2,699 | Living in a war-affected area was independently associated with constipation (adjusted OR 1.48). |

| 38 | Di Maio and Nandi,[91] 2013 | Israel-Palestine | Palestinian boys 10–14 years in the West Bank | 45,419 | Closure of the border between Israel and the West Bank significantly increased the probability of child labour. A 10 day increase in the quarterly number of school closure days increased the probability of child labour by 11%. |

| 39 | Dickson-Gómez,[99] 2002 | El Salvador | Former child soldiers | 4 | Describes the experiences of child soldiers including witnessing and being subjected to torture, imprisonment, displacement, loss of family, being orphaned, assumption of adult roles and responsibilities, child marriage, teen pregnancy, and difficulty reintegrating into their communities. |

| 40 | Edwards et al,[151] 2012 | Afghanistan | Trauma patients in US military combat facilities | 1,205 | Data from JTTR. Children <15 years accounted for more than half of severe head and neck injuries. Children ≤7 years or younger were more likely injured by mortar fragments, while children 8–14 years were higher risk for land mine or UXO injury. |

| 41 | Edwards et al,[152] 2014 | Afghanistan and Iraq | Trauma patients in US military combat facilities | 1,205 | Data from JTTR. Children <15 years accounted for 25% of civilian admissions 2002–2010. Infants and young children ≤3 years most often required neurosurgical procedures. Extremity amputation and external fixation were more common in children >4 years |

| 42 | Eide et al,[153] 2010 | multiple | Children of US military personnel | 169,986 | During deployment, children of single parents had lower outpatient visit rates while children of married parents had increased visit rates. Parent age <24 years and single marital status were associated with lower visit rates. There was an overall increase in outpatient visits and well-child visits during deployment compared with periods when the parent was not deployed. |

| 43 | Elbert et al,[154] 2009 | Sri Lanka | 5th graders in north-eastern Sri Lanka | 420 | 77% of children had been displaced at least once. 92% had experienced violence from the war including combat, bombing, shelling, or witnessing the death of a loved one. |

| 44 | Erjavec and Volcic,[100] 2010 | Former Yugoslavia | Adolescent girls born of war-related rape | 11 | The adolescents describe social isolation from the mother's ethnic group, as well as being assaulted, shot at and threatened with rape. They also described taking on the role of carer for incapacitated mothers. |

| 45 | Feldman et al,[106] 2013 | Israel-Palestine | War-exposed and non-exposed children 1.5–5 years | 232 | War-exposed cohort had lower baseline cortisol levels and less reactivity to stress than the non-exposed cohort. Children’s baseline cortisol levels were independently related to maternal baseline cortisol lower maternal reciprocity, and greater maternal psychopathology. |

| 46 | Garfield and Leu,[121] 2000 | Iraq | Children U5 | 8,191 | Used MICS 1996 survey data. U5 mortality more than tripled during the war, then fell afterwards during post-war conflict and sanctions, but remained at least twice the pre-war level. |

| 47 | Gasparovic et al,[76] 2004 | Former Yugoslavia | Case report | 1 | 9 year old girl with injuries due to UXO, including intracranial shrapnel, intracardiac shrapnel, multiple intestinal perforations, multifragmentary fracture of the right distal humerus, and explosive injuries of the soft tissues of the right thigh and right foot. |

| 48 | Gataa and Muassa,[155] 2011 | Iraq | Patients at 2 facilities | 551 | One-fifth of patients with maxillofacial injuries were children <15 years |

| 49 | Geltman et al,[50] 2005 | Sudan | Sudanese unaccompanied minors in foster care in the US | 304 | One fifth of the youth reported being tortured and 29% sustained war-related physical injuries. They reported near-drowning, near-suffocation, head trauma, and loss of consciousness. The youths reported seeking health care for a variety of somatic symptoms including headaches, stomach aches, anorexia, and chest pains. Nearly 1/3 had sleep disturbances. |

| 50 | Gessner,[62] 1994 | Afghanistan | Displaced and resident families in Kabul | 612 | Displaced families lived with a mean of 15 people per room compared with residents, who had a mean of 2 people per room. The average number of people per toilet for displaced persons was 44, and two locations for displaced people had no working toilets. |

| 51 | Ghobarah et al,[57] 2004 | multiple | Populations in countries after civil war | Not specified | Significant reduction in DALYs for all disease categories in children <15 years, most commonly due to infectious diseases, and with the most severe reductions in children under 5. This effect was found for countries experiencing civil war as well as countries adjacent to them. |

| 52 | Goma Epidemiology Group,[156] 1995 | Rwanda | Children in three refugee camps | Not specified | Mortality estimates ranged 20-120/10,000/day for unaccompanied children and 100-800/10,000/day unaccompanied infants. High rate of death attributed to diarrhoea. . |

| 53 | Green,[51] 2007 | multiple | Case report | 3 | 3 child victims of torture, reported child labour, slow insertion of a knife into the child's thigh to extract information from the parents, and witnessing torture, including witnessing a parent tortured to death. The children reported recurrent nightmares and school absenteeism. |

| 54 | Greene et al,[157] 2014 | Iraq | Case report | 1 | 3 year old girl with blast injuries to the right arm and chest, who required highly specialised thoracic surgery and was hospitalised for 16 days. |

| 55 | Grein et al,[158] 2003 | Angola | Refugees in 4 camps | 6,599 | 18% of the population was U5. U5 mortality was four times above baseline. Main causes of child death were malnutrition, fever and malaria. Children accounted for one-fourth of deaths related to war violence, and 55% of disappearances. |

| 56 | Guha-Sapir and van Panhuis,[123] 2003 | multiple | Children in multiple conflict zones | Not specified | Analysed data from mortality surveys in 7 populations in Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia, and Sudan. The relative risk of dying during conflict differed based on context and appeared to be associated with the fragility of the affected population. |

| 57 | Guha-Sapir and van Panhuis,[122] 2004 | multiple | Populations affected by armed conflict | Not specified | In pooled data from 37 datasets, children ≥5 years have a higher relative risk of dying during conflict compared to children U5. There were wide variations in mortality rates between conflicts. |

| 58 | Guy,[52] 2009 | DRC | Case report | 3 | The 3 children were subjected to physical and psychological torture and reported participation in violence. The three children had a combined total of 403 medical complaints. Clinical exam revealed 275 physical findings that were consistent with the torture mechanisms described by the children. |

| 59 | Hagopian et al,[69] 2010 | Iraq | Child cancer patients at a single facility | 698 | Leukaemia incidence in children aged <15 years presenting to the referral facility in Basra more than doubled over the period 1993–2007. |

| 60 | Halileh and Gordon,[131] 2006 | Israel-Palestine | Children 6–59 months in Gaza and the West Bank | 3,331 | 37% of children were anaemic, with linear decrease in prevalence of anaemia with increasing age. Independent risk factors included age <24 months, living in refugee camps, living in Gaza, and household income being affected by the conflict. |

| 61 | Hanevik and Kvåle,[77] 2000 | Eritrea | Landmine injury patients in 5 hospitals | 248 | Chart review of 248 patients with landmine injuries. 41% of patients were under 15 years, and 22% were 15–19 years old. |

| 62 | Helweg-Larsen et al,[29] 2004 | Israel-Palestine | Patients presenting to two emergency departments | 962 | Chart review of intentional injuries pre-conflict and during Intifada. Marked rise in intentional injuries during conflict. 3% of patients were <10 years old and 8% of patients were 10–14 years old. Head injuries were mostly caused by firearms and were more frequent among the very young children. |

| 63 | Henrich and Shahar,[132] 2013 | Israel-Palestine | 7th-10th graders in southern Israel | 362 | Greater rocket attack exposure predicted an increased aggression in boys, with increased odds of committing violence over the course of the study. |

| 64 | Hicks et al,[53] 2011 | Iraq | Iraqi civilians killed during the conflict | 92,614 | Data from Iraq Body Count database 2003–2008: 2,146 (3.5%) deaths were children under age 18. 36,900 (61.0%) civilian victims of unreported age. Children were killed by all measured methods, including execution, execution with torture, small arms gunfire, suicide bomb, vehicle bomb, roadside bomb, mortar fire, and air attacks both with and without ground fire |

| 65 | Hicks et al,[159] 2011 | Iraq | Death or injury due to suicide bomb | 42,928 | Data from Iraq Body Count database 2003–2010: Children accounted for 14% of deaths due to suicide bombs and for a higher proportion of deaths due to suicide bombs than from general armed violence. 16% of suicide bomb events resulted in the death of at least one child. |

| 66 | Hisle-Gorman et al,[160] 2015 | multiple | Children 3–8 years old of deployed US military personnel | 487,460 | Parental deployment was associated with increased rates of child maltreatment. For the children of injured veterans, there was a 24% increase in child maltreatment visit rates for each additional parent injury diagnosis. |

| 67 | Hoffer and Johnson,[161] 1992 | Iraq | Children with shrapnel wounds at US military combat facility | 19 | 19 of >100 children with shrapnel wounds had associated open fractures. Mechanism of injury included UXO, aerial bombardment, and bullet wounds from combat. Open fractures from shrapnel were most common in the tibia and fibula, and 9 children had bilateral fractures from shrapnel. |

| 68 | Inwald et al,[42] 2014 | Afghanistan | Intensive care patients at a British military combat facility | 811 | Data from Bastion intensive care unit database and JTTR. 14% of intensive care admissions were children, median age 8 years. 71% were trauma admissions, of which 65% had blast injuries, 20% gunshot wounds, and 15% blunt trauma. Body region of trauma: 45% extremities, 35% face/eyes, 26% head, 20% abdomen, 11% thorax, and 4% pelvis |

| 69 | Kandala et al,[59] 2009 | DRC | Children U5 in DRC | 9454 | Higher prevalence of childhood diarrhoea, acute respiratory infection and fever in provinces experiencing armed conflict |

| 70 | Kinra and Black,[78] 2003 | Former Yugoslavia | Landmine injury patients in Bosnia | 4,064 | ICRC database 1991–2000 (during and post-conflict). 14% of patients were children, the majority who were injured during recreational activities. Children were more likely to be injured during peacetime when compared with adults. |

| 71 | Klimo et al,[31] 2010 | Afghanistan | Neurosurgical patients at a US military combat facility | 43 | Data from surgeon’s personal records. 40% of paediatric patients (<18 years) were under 5 years of age The average age of paediatric patients was 7.5 years. Penetrating brain injuries were most common. IED most frequent source of projectile, followed by rocket, landmine, mortar and gunshot wound. |

| 72 | Kvaskoff et al,[162] 2013 | WWII | Cohort of French women born in 1925–1950 | 75,918 | There was a linear relationship between the level of World War II food deprivation before 20 years of age and endometriosis risk. |

| 73 | Lee et al,[124] 2006 | Myanmar | Households living in conflict zone | 1290 | Infant mortality rate in the conflict zone was nearly double and U5 mortality rate was nearly triple the level of the national rates. |

| 74 | Liu et al,[163] 2014 | multiple | Live births to war refugee women in Sweden | 20,723 | Significantly higher odds of preterm (OR 1.39, 95CI: 1.13–1.72) or very preterm birth (OR 2.15, 95CI: 1.37–3.38) during the 1st year of residency in Sweden. The risk continued beyond the first year, with increased risk of very preterm birth (OR = 1.54 95% CI 1.07–2.21) during the third to fifth year of residence. |

| 75 | Longombe et al,[116] 2008 | DRC | Child rape survivors | 7 | Case report of the gang rapes by armed forces of a 6 year old and a 12 year old, respectively. The children developed vesicovaginal fistulae. |

| 76 | Maclure and Denov,[113] 2006 | Sierra Leone | Former child soldiers | 36 | Description of the children's experiences, including physical abuse, psychological torture, witnessing of violence, drug use, child labour, and the use of children as human shields. |

| 77 | Mann,[101] 2010 | DRC | Congolese undocumented refugee children in Tanzania | >100 | Children describe social isolation, stigmatization, dehumanization, harassment and xenophobia, child labour, exploitation, and physical abuse. Fear of being reported to the police, imprisoned or deported. The children also describe lack of agency and barriers in access to education. |

| 78 | Manoncourt et al,[63] 1992 | Somalia | IDPs and residents in Mogadishu | 4169 | High child mortality rates (per 1000 live births), which varied by IDP status and residence. IDPs in camps with U5 mortality rate (MR) 240.6 (95CI: 206.0–275.2), and 5–14 MR 167.1 (95CI: 140.5–193.7). IDPs in towns with U5MR 86.2 (95CI: 50.1–122.3), and in 5–14 MR 89.7 (95CI 52.2–127.2). Residents with U5MR: 115.4 (95CI: 85.6–145.2), 5–14 MR 57.8 (95CI: 38.7–76.9). Markedly limited access to water for IDPs in camps. |

| 79 | Martin et al,[32] 2010 | Iraq | Paediatric neurosurgical patients at a US military combat facility | 42 | Prospective study. 15% of civilian patients were children <18 years, 62% of whom were ≤8 years. 52% had penetrating head injuries, 24% had closed head injuries, and 12% had penetrating spinal injuries. 22% overall mortality in children, and 32% mortality in children with penetrating head injuries. |

| 80 | Masterson et al,[87] 2014 | Syria | Syrian refugee women in Lebanon | 452 | Describes limited access to antenatal and delivery care, with high rates of complications and adverse birth outcomes, including low birth weight, preterm delivery, and infant mortality. Less than half reported any breastfeeding, citing inability to breastfeed, illness, and constant displacement as reasons. 75.8% reported beating their children more than usual. |

| 81 | Mathieu et al,[33] 2015 | Afghanistan | Combat facility paediatric patients with extremity trauma | 155 | Mean age of patients was 9 years. 46% were <8 years. Younger children more likely to have noncombat-related injuries (NCRI). Male to female ratio 3:1. 77 combat-related injuries (CRI) including 19% bullet wounds, 42% fragment wounds, 39% blast wounds. Motor vehicle crashes, falls and burns were the most common noncombat-related mechanism of injury. Injury severity score significantly higher for CRI. |

| 82 | Matos et al,[34] 2008 | Iraq | Paediatric trauma patients treated in a US combat facility | 1132 | Data from hospital records. 97% of patients were >8 years old. 63% of young children (≤8 years) and 83% of older children and adults had penetrating injuries. Young children had more severe injuries. Young age was independently associated with higher mortality. |

| 83 | McGuigan et al,[35] 2007 | Iraq | Paediatric trauma patients treated in a US combat facility | 99 | Data from hospital records. 55% of patients were <13 years old. 79% of injuries were due to battle or crossfire, the majority were blast wounds or penetrating trauma. None of the children had protective armour, and most had multiple injuries. Blast victims had a combination of blunt, penetrating, and thermal injuries. 9% mortality. |

| 84 | Metreveli and Vosk,[164] 1994 | Republic of Georgia | Child casualties in Georgian Civil War | 5 | Case report of five children injured or killed by hand grenades or firearms during the civil war. Treatment was hampered by a shortage of medical equipment and supplies. |

| 85 | Miller et al,[88] 1996 | Former Yugoslavia | Children treated in a referral facility, Sarajevo | 60 | Marked reduction in services, number of beds, number of staff, access to medications, barriers to care and length barriers to returning to family, for up to 18 months, due to the war. Of hospitalised children, 20% had experienced the death of a close relative in the war and 38% had one or more close family members injured. |

| 86 | Momeni and Aminjavaheri,[46] 1994 | Iran-Iraq | Children exposed to mustard gas | 14 | Compared with adults, the children had earlier onset of symptoms and a different clinical pattern. Children's first symptoms were cough and vomiting. Facial involvement was most common. Skin bullae appeared sooner, and the children developed more severe ophthalmic manifestations. |

| 87 | Montgomery and Foldspang,[165] 2001 | multiple | Child asylum seekers in Denmark | 311 | Predictors of sleep disturbance (frequent nightmares, delayed sleep onset, and night-time awakenings) included violent death of grandparents before the child's birth, torture of one or both parents, and being scolded more than previously. Being accompanied to Denmark by both parents reduced the risk of sleep disturbance (OR 0.3 and p<0.0005). |

| 88 | Mujkic et al,[166] 2008 | Former Yugoslavia | Child deaths due to injury 1986–2005 | 4,660 | During the war, the rates of child homicide and suicide using weapons more than tripled and unintentional child deaths with weapons increased more than 6-fold compared to pre-war period. After the war, these rates gradually returned to pre-war levels. |

| 89 | Nelson et al,[117] 2011 | DRC | Child survivors of sexual violence | 389 | Children <18 years were more likely than adults to have been gang raped, raped by a civilian, and raped during the day. Education was protective. The study found an increase in civilian-perpetrated rape during conflict. Nearly 1/4 of child rape survivors had physical sequelae and 19% reported pregnancy resulting from rape. 18% of the children reported efforts to bring the perpetrator to justice, most often with civilian perpetrators. |

| 90 | Nicaragua Health Study Initiative,[81] 1989 | Nicaragua | Households in two towns | 89 | Comparison of a town in a peaceful region with a town in a conflict zone. Children in town experiencing armed conflict had higher prevalence of stunting, lower odds of having an immunization card, lower rate of U5 vaccination completion, and twice the odds of being an orphan. |

| 91 | Nielsen et al,[126] 2006 | Guinea-Bissau | Children <5 years near Bissau | 8933 | U5 mortality doubled during the first six months of the war. In the later part of the war, U5 mortality began to return to baseline, but mortality for girls remained significantly higher than pre-war. Maternal education was protective against U5 mortality. |

| 92 | Novo et al,[85] 2009 | Former Yugoslavia | Rubella cases in Bosnia | 342 | Post-war rubella outbreak investigation revealed that MMR vaccination coverage dropped from 93.6% in Bosnia pre-war to 56.8% during the last two years of the war. Partially- and unvaccinated patients never received catch-up vaccinations. |

| 93 | O'Hare and Southall,[82] 2007 | multiple | Children in Sub-Saharan Africa | Not specified | Data from UNICEF SOWC 2006 report in 42 Sub-Saharan African countries. Median U5 mortality rate in countries with recent conflict was 197/1000 live births, significantly higher than countries without recent conflict (137/1000 live births, p = 0.009). Women in countries with recent conflict were less likely to deliver with a skilled birth attendant, 1 year olds had lower DTP vaccination rates, and primary school enrolment was lower. |

| 94 | Pannell et al,[36] 2015 | Afghanistan | Paediatric trauma patients in a NATO combat facility | 263 | Data from JTTR. 11.7% of trauma patients were children, median age 9 years (range 3 months—17 years), nearly 1/3 were under 6 years. 62% had battle injuries. Injury mechanism: 42% blast injuries, 17% GSW, 16% motor vehicle crash, 8% falls and 4% burns. More than half of children had penetrating injuries. ISS was higher for children <15 years. 8% inpatient mortality. |

| 95 | Patel et al,[104] 2012 | Uganda | IDPs in northern Uganda | >116 | 116 In-depth interviews and 16 focus group discussions. Displacement and low security led to disruption of community structure and social norms; this was associated with changes in sexual behaviour. Girls living in IDP camps were vulnerable to sexual exploitation, violence, economic and food insecurity, and had barriers in access to education and health care. |

| 96 | Pesonen et al,[108] 2008 | WWII | Helsinki birth cohort | 1,704 | Girls separated from their parents in early childhood were twice as more likely (OR 2.1, 95CI: 1.2–3.7) to have their menarche before or at the age of 12 than after the age of 13, compared with non-separated girls. |

| 97 | Pesonen et al,[107] 2010 | WWII | Helsinki birth cohort | 282 | Adults who had been separated from both parents during early childhood had higher salivary cortisol and plasma ACTH concentrations and greater salivary cortisol reactivity to during Trier Social Stress Test compared with non-separated. Gendered differences were found in baseline cortisol, ACTH, and cortisol reactivity. Age at separation from both parents predicted salivary cortisol, plasma cortisol, and plasma ACTH. |

| 98 | Pesonen et al,[109] 2011 | WWII | Helsinki birth cohort | 2,725 | Young men separated temporarily from both parents during early childhood had lower intelligence scores than non-separated men. Findings differed by length of separation and age at the time of separation. Verbal ability was particularly impacted in boys separated from their parents before school age. |

| 99 | Poirier,[90] 2012 | multiple | Children in Sub-Saharan Africa | Not specified | Data from 1950–2010 in 43 countries. Armed conflict and military expenditure increase the rate of children not attending school and have a negative effect on secondary school enrolment rate. |

| 100 | Qouta et al,[133] 2008 | Israel-Palestine | School children in Gaza | 865 | Witnessing severe military violence was associated with aggressive and antisocial behaviour in school children. Parenting practices appear to be a moderating factor. |

| 101 | Radoncic et al,[167] 2008 | Former Yugoslavia | Births at a tertiary facility in Bosnia | 101,712 | Perinatal mortality was decreasing before the war. There was a significant increase during the war and early post-war period and decline again to pre-war levels in 2001. The main causes of perinatal mortality were respiratory distress syndrome, birth asphyxia, congenital malformations, and intracranial haemorrhage. |

| 102 | Radonic et al,[79] 2004 | Former Yugoslavia | Patients with antipersonnel mine injuries | 422 | Data during the war 1991–1995 in southern Croatia. Children accounted for 7.8% of antipersonnel mine injuries and were most commonly injured while playing with the mines, on the way to school, or near their home. The mean age of injured children was 10.5 years. |

| 103 | Rashid,[54] 2012 | Kashmir, India/ Pakistan | Children who were detained and tortured in Kashmir | 43 | Data from personal accounts of children-in-conflict-with-law in Indian-held Kashmir. The children describe lengthy imprisonments in crowded facilities together with adults, forced labour, and inadequate food. Torture methods described included being stripped, blindfolded, having limbs stretched, electrocution of private parts and of limbs, hanging from ceiling by arms, beatings, rollers, breaking teeth, and threats to family. The children describe poor physical health and social isolation after release. |

| 104 | Rees et al,[94] 2013 | Timor-Leste | Women in an urban area and a rural village | 1513 | Victimization and war-related trauma increased the odds of Intermittent explosive disorder in women. Women with IED reported excessive and harmful punishment of their children. |

| 105 | Rentz et al,[97] 2007 | multiple | Children <18 years who experienced substantiated maltreatment in 2000–2003 | 147,982 | Texas child maltreatment data from 2000 to 2003: Substantiated child maltreatment in military families doubled after October 2002 (Rate ratio 2.15, 95CI: 1.85, 2.50), after controlling for child’s age, race/ethnicity, and gender. The rate of child maltreatment in military families increased by approximately 30% for each 1% increase in the percentage of active duty personnel departing to or returning from operation-related deployment. The majority of child maltreatment in military families was perpetrated by a parent. |

| 106 | Reyna,[168] 1993 | Iraq | Paediatric patients treated in a US combat facility | 50 | Data from hospital records. Description of 50 paediatric patients 0–19 years seen at an evacuation hospital in Kuwait. 80% were trauma patients, of which 65% had penetrating injuries. Injuries included shrapnel wounds, gunshot wounds, burns, motor vehicle accidents, crush injuries, and falls. There were no trauma-related deaths. |

| 107 | Roberts et al,[127] 2004 | Iraq | Households in Iraq | 6300 | Household survey found that crude infant mortality increased from 29 per 1000 live births pre-invasion to 57 deaths per 1000 live births post-invasion [95% CI 0–64]. Violence accounted for more than half of recorded child deaths in the post-invasion. |

| 108 | Rodríguez and Sánchez,[93] 2012 | Colombia | Children 6–17 years in Colombia | 20,642 | National survey found that violent attacks significantly increase the risk of school drop-out. An increase by one standard deviation of armed conflict exposure increased the joint probability of child labour and school drop-out by 13% in children 12–17 years. The effect appeared to be long-term, with adults in areas affected by conflict having lower educational outcomes. |

| 109 | Saile et al,[95] 2014 | Uganda | Households in Gulu and Nwoya districts | 283 | Traumatic war exposure in female guardian independently predicted child-reported experiences of abuse in the family. Partner violence between guardians and PTSD-symptoms in male guardians were the major proximal risk factors for child-reported victimization, suggesting that war exposure and subsequent trauma may be a mediating factor in violence against children. |

| 110 | Salignon and Legros,[134] 2002 | Republic of Congo | Residents of Mindouli | 10,026 | 83.5% of the population were displaced by the war and had returned to their homes in Mindouli during the 3 months preceding the survey. 195 U5 deaths were reported in the 6 months preceding the survey, accounting for 13% of the U5 population of Mindouli in November 1999. The U5 mortality rate exceeded 10 deaths/10,000/day November 1999-January 2000. Causes of U5 death were malnutrition (54,4%), fever (17.4%), diarrhoea (6.7%), and 21.5% other cause |

| 111 | Samms et al,[169] 2010 | Iraq | Case report | 1 | 16 year old with a gunshot wound to the pelvis and possible blast injury to the abdomen. The patient had an 83 day hospital course, required 30 operations, and was discharged to a local hospital. |

| 112 | Santavirta,[170] 2014 | WWII | People born in Finland 1933–1944 registered in the 1950 census | 66,053 | Men who were evacuated to foster care in Sweden at age <4 years had mortality risk 1.3 times higher than their counterparts who were not evacuated. There were no other significant mortality differences based on gender, age at time of evacuation, or between evacuation-status discordant siblings. |

| 113 | Schiff et al,[171] 2006 | Israel-Palestine | 7th-10th graders in Herzeliya, Israel | 1,150 | 1/3 respondents were in the proximity during an attack and 40% knew someone who was injured (psychological proximity). Physical and psychological proximity to attacks were significantly associated with alcohol consumption, when controlling for PTSD and depressive symptoms. |

| 114 | Schiff et al,[172] 2007 | Israel-Palestine | Jewish 10th and 11th graders in Haifa | 960 | Close physical exposure to armed conflict predicted higher levels of alcohol consumption, binge drinking among drinkers, and cannabis use. |

| 115 | Schiff et al,[173] 2012 | Israel-Palestine | Jewish and Arab Israeli 7th-11th graders | 4,151 | The youth reported high rates of exposure to war events. Cumulative exposure to war events was significantly associated with alcohol and drug consumption and involvement in school violence. |

| 116 | Schlecht et al,[105] 2013 | Uganda | Displaced Ugandan and Congolese refugee youth | 133 | Armed conflict resulted in breakdown of traditional community social structure and associated protective marriage practices. Displacement was also associated with social isolation and barriers in access to education. These social changes and challenges were associated with earlier sexual debut without involvement or knowledge of parents/caregivers, teen pregnancy, sexual exploitation of girls, transactional sex. |

| 117 | Shemyakina,[92] 2011 | Tajikistan | Households with school age children across Tajikistan | 6,160 | Based on 2 surveys (one representative at national level and one at regional and urban/rural level). Children 8–15 years old in conflict-affected area were less likely to attend school. Damage to household dwelling negatively associated with the enrolment of girls. Nationally, men and women of school age during the war were less likely to complete nine grades of schooling compared to their pre-war counterparts. |

| 118 | Shuker,[174] 1985 | not reported | Case report | 1 | 7 year old child with multiple high-velocity wounds sustained from artillery shelling, including avulsion of 6cm of the left mandible. The mandible was stabilised with a K-wire, resulting in spontaneous regeneration of the entire osseous defect. |

| 119 | Skokic et al,[61] 2006 | Former Yugoslavia | Newborns in Tuzla Canton 1992–2003 | 59,707 | During the war: 20% fewer live births than pre-war and higher prevalence of premature delivery compared with pre- and post-war. Average birth weight of term newborns was 200 and 300 grams lower than pre- and post-war, respectively. Barriers to care during conflict evidenced by significantly fewer births attended by trained health providers and fewer prenatal visits. |

| 120 | Slim et al,[37] 1990 | Lebanon | Patients with war-related abdominal injuries at a single facility | 270 | Children <16 years accounted for nearly 1/5 of abdominal trauma admissions. 70% of children had penetrating injuries from shrapnel, bullets, stab wounds, and blast explosions. The remaining 30% had blunt abdominal trauma. The children had 4.8% overall mortality; however patients transferred from other facilities had 55.6% mortality. |

| 121 | Soroush et al,[80] 2010 | Iran-Iraq | Patients with landmine or UXO injury | 3,713 | Data from hospital records of 3713 patients in western and south-western Iran. 41.8% of patients with landmine or UXO injuries were <18 years old. |

| 122 | Spiegel et al,[175] 2011 | Somalia | Refugee households in Dadaab camps | 753 | In a household survey of newly arrived refugees, 44 deaths reported, 29 (66%) were in children under 5. |

| 123 | Spinella et al,[40] 2008 | Afghanistan and Iraq | Paediatric patients treated in 7 US combat facilities | 1,305 | Data from PASBA database. Report on paediatric trauma admissions December 2001—May 2007, or 7.1% of all trauma admissions. Children were severely injured at admission, had longer hospital stays, and accounted for 13% of trauma deaths. Age <6 years was associated with higher mortality rate (10.7% compared with 3.8% in children 6–17 years). |

| 124 | Stern et al,[176] 1995 | Iraq | Case report | 1 | 8 year old with aplastic anaemia, only known exposure was that his home was situated near to burning oil wells |

| 125 | Terzic et al,[43] 2001 | Former Yugoslavia | Children treated at a tertiary care facility | 94 | Chart review of paediatric patients treated for war injuries. Most children were wounded by shelling and explosive devices, most commonly in the extremities. The most severe wounds were caused by shelling. 39.4% of children were permanently disabled and 3.3% died. |

| 126 | Trenholm et al,[114] 2013 | DRC | Male former child soldiers | 12 | Ethnographic study. Boys reported abduction, forced recruitment, and poverty as reasons for entering the military. They describe beatings, forced marches, sleep deprivation, starvation, substance use, witnessing rape, and being forced to rape. The boys describe normalization of sexual violence, with rape considered a bounty of war and also as means to release anger or reap revenge. |

| 127 | Valente et al,[84] 2000 | Angola | Polio cases in Angola | 1,093 | Description of a polio outbreak among displaced persons in Luanda. During a vaccination campaign in response to the outbreak, nearly 30% of districts could not be reached due to the conflict. |

| 128 | Van Herp et al,[64] 2003 | DRC | Households in 5 conflict-affected regions of DRC | 4,527 | Threshold and emergency level U5 mortality rates at the front line, primarily due to malnutrition and infections. Context-specific variations in direct and indirect exposure to combat and barriers in access to acute and preventive health care. |

| 129 | Van Leent and Hopkins,[177] 1951 | WWII | Refugee children in Australia | 4,721 | Sampled nearly 1/5 of refugee children, found low BCG vaccination rates. 36% were Mantoux positive, with a linear rise in Mantoux positivity with age: 3.9% positive at 1 year, up to 78% positive at 15 years. |

| 130 | Veale and Dona,[178] 2003 | Rwanda | Street Children in Rwanda | 290 | 87% came to the streets after the 1994 genocide. More than 3/4 had lost at least one parent, and 1/3 reported both parents were dead. 42% were homeless. The majority cited living on street due to changes in family structure, including loss of one or both parents, parent remarriage, becoming unaccompanied, being fostered in another family, or the closure of an unaccompanied children’s centre. |

| 131 | Verelst et al,[119] 2014 | DRC | 2nd and 3rd graders in Ituri district | 1305 | 499 children (38.2%) reported having been victims of sexual violence. The risk of sexual violence increased with exposure to war-related violence, separation from family, being injured during the war, imprisonment, and association with armed groups. |

| 132 | Villamaria et al,[44] 2014 | Afghanistan and Iraq | Paediatric vascular trauma patients treated in US combat facilities | 155 | Data from 2002–2011. The majority of vascular injuries in children were caused by blast injuries (58%), followed by bullets (37.4%) and falls (1.9%). Extremity injuries were more common while torso injuries were more lethal. |

| 133 | Vranković et al,[45] 1997 | Former Yugoslavia | Case report | 10 | In 10 paediatric penetrating head injury patients, 4 were injured by bullets and 6 by shrapnel. Patients with shrapnel wounds had associated cerebral oedema. All gunshot wound patients survived; half of patients with shrapnel wounds died. 4 patients had moderate neurological deficits. |

| 134 | Weile et al,[55] 1990 | Chile | Chilean refugee children in Denmark | 58 | Follow up of Cohn 1979. In child survivors of torture living as refugees in Denmark, there was an increase in the number of somatic symptoms and in the prevalence of symptoms over time. At follow up, 90% of children had one or more symptoms. Children who had continuous symptoms at the first study had significantly higher medication use. Number years lived in Denmark positively correlated to number of symptoms. |

| 135 | Wen et al,[70] 2000 | Vietnam and Cambodia | Children with leukaemia | 2,343 | Pooled data from three studies shows increase in the risk for AML of the children of veterans who served in Vietnam or Cambodia (OR 1.7; 95% Cl: 1.0, 2.9). This risk was increased in fathers who had two or more tours of duty (OR = 5.0; 95CI: 1.0, 24.5). |

| 136 | Wilson et al,[38] 2013 | Afghanistan | Paediatric trauma patients treated in a US combat facility | 41 | Data from facility trauma registry. 10% of trauma admissions were children, 71% were boys, and 59% were battle-related. More than 2/3 had penetrating injuries, most often from IEDs and landmines. 3/4 of injuries were severe, with AIS score ≥ 3, and 14.6% died. |

| 137 | Woods et al,[39] 2012 | Afghanistan and Iraq | Paediatric trauma patients treated in British combat facilities | 176 | Data from JTTR. Half of paediatric (<16) trauma cases were less than eight years old. The most common mechanism of injury was explosive injury (59%), followed by gunshot wound (20.5%), and motor vehicle crash (8.5%). The mortality rate was 11%. 70% of mortality was due to explosive injury and 15% due to motor vehicle crashes. Half of deaths were due to head injuries. |

| Search updates 25 April 2017 | |||||

| Author | Conflict zone | Population | Sample size | Summary of findings | |

| 1 | Bayarogullari et al,[179] 2016 | Syria | Case report | 2 | Two children with complex shrapnel wounds resulting in vertebral artery pseudoaneurysms. One patient lost to follow up due to displacement. |

| 2 | Ceri et al,[180] 2016 | Iraq | Yazidi refugee children in three camps | 42 | More than 2/3 of children reported sleep disturbances and >1/3 had somatic complaints |

| 3 | Charchuk et al,[58] 2016 | DRC | Children in Bilobilo IDP camp and Mubi village | 600 | IDP camp residence predicted falciparum malaria in children (OR 2.6, 95% CI: 1.2–5.7). Bed net ownership and use were significantly lower for the children from the IDP camp compared to the children from the village. |

| 4 | Chi et al,[102] 2015 | Burundi and Uganda | Health workers and women living in Burundi and Northern Uganda | 115 | Participants linked armed conflict with limited access to maternity and reproductive health services, poor quality of care, and increased neonatal morbidity and mortality. Conflict resulted in destruction and looting of facilities, targeted killing and abduction of health workers, and migration of health workers. Barriers in care resulted in increased use of traditional birth attendants. Girls 12–18 years from disadvantaged backgrounds were noted to be at high risk for sexual exploitation, unintended pregnancy, and subsequent health complications. |

| 5 | Cook et al,[49] 2015 | Myanmar | Karen refugees in Minnesota, USA | 179 | Children described witnessing and being subjected to war-related violence, including witnessing parents and community members being tortured and killed by soldiers, repeated and forced displacement, being beaten, child labour, and being forced to join the military. |

| 6 | Denov and Lakor,[115] 2017 | Uganda | Children born to mothers abducted by the Lord's Resistance Army | 60 | Children report witnessing combat and mass executions, seeing injured children and dead bodies. They reported being orphaned, being abandoned by parents, going without food or water, and lack of access to health care and education. Stigma and social exclusion from parents, families and communities led some children to describe life during war as preferable because they were loved, had a caring father present, and a sense of family. |

| 7 | Duque,[181] 2017 | Colombia | Children in Colombia | 13,344 | Violence exposure in first trimester of gestation and in early childhood was associated with decline in math reasoning, general knowledge, and Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test scores. |

| 8 | Guha-Sapir et al,[47] 2015 | Syria | Civilian violent deaths in Syria 2011–2015 | 78,769 | Children accounted for >16% of civilian deaths in non-state controlled areas and >23% of civilian deaths in government-controlled areas. The risk of death from different combat activities varied by location, however, children in all areas were more likely than men to die from air bombardments, shells, ground level explosives, and chemical weapons. 852 children were killed by execution, including execution after torture. |

| 9 | Hemat et al,[182] 2017 | Afghanistan | Trauma patients at single facility | 35,647 | Paediatric trauma patients at Kunduz Trauma Centre Jan 2014- June 2015: Children accounted for 50% of patients registered in the emergency department and 41% of operated patients. |

| 10 | Khamaysi et al,[183] 2015 | Syria | Case report | 5 | Report on 5 patients with traumatic bile leaks from war injuries, including two children. |

| 11 | Klimo et al,[30] 2015 | Iraq and Afghanistan | Paediatric neurosurgical patients at US military combat facilities | 647 | Data from JTTR. Review of neurosurgical cases 2004–2012. 76% of patients were boys, with a median age of 8 years. 60% of patients were under 9 years of age. 61% had penetrating head injuries. Most commonly mechanism of injury was IED explosion, blast, gunshot wound, and mortar. In-hospital mortality was 24%. |

| 12 | Lindskog,[125] 2016 | DRC | Infants born in DRC | 53,768 | Uses DHS data to analyse infant mortality among 15,103 mothers and 53,768 children. Infant mortality was higher during the war years compared with pre-war and post-war. There was a linear relationship between post-neonatal infant mortality and the number of conflict events |

| 13 | Nnadi et al,[83] 2017 | Nigeria | Polio cases in Borno | 4 | There were 4 reported cases of Polio in the region. Two infected children were unvaccinated, and two were partially vaccinated. In the two years preceding the case report, 50% of settlements in Borno were inaccessible to public health programmes. |

| 14 | Rabenhorst et al,[96] 2015 | Afghanistan and Iraq | US Air Force personnel deployed >30 days | 99,679 | There were no overall changes in substantiated child maltreatment (CM) rates post-deployment compared to pre-deployment, however rates of child injury increased post-deployment (RR1.6, 95% CI: 1.31, 2.01), as well as rates of moderate and severe maltreatment (RR 1.9, 95% CI: 1.34, 2.80) and CM involving alcohol use (RR 1.5, 95% CI: 1.11, 2.15). |

| 15 | Rouhani et al,[118] 2015 | DRC | Women raising children born from sexual violence | 757 | More than a third report stigma toward their child from the community and 2/3 reported often seeing their assailant and/or remembering the sexual assault when looking at the child. Stigma and maternal mental health disorder was associated with negative parenting attitudes. Family and community acceptance were associated with adaptive parenting attitudes. |

| 16 | Stark et al,[65] 2015 | Uganda | Congolese and Somali refugees in Kampala | >215 | 175 In-depth interviews, 40 key-informant interviews and 51 focus group discussions. Children reported discrimination in schools and teachers encouraging xenophobia Conversely, some reported reduced school fees and accommodations made for prayer. Children reported social marginalization in the community, barriers in access to sanitation, assault, and lack of access to health care and legal and protective services. |

| 17 | Sullivan et al,[98] 2015 | multiple | Californian children in public civilian schools, grades 7, 9, and 11 | 688,713 | Military-connected secondary school students reported higher levels of physical violence (OR 1.47, 95% CI: 1.43–1.50) and nonphysical harassment (OR 1.42, 95%CI: 1.38–1.45). They had twice the odds of carrying a gun to school (OR 2.2, 95% CI: 2.10–2.30), and nearly twice the odds of carrying a knife or other weapon to school (OR 1.81 (95% CI: 1.75–1.88). |

| 18 | Weishut,[56] 2015 | Israel-Palestine | Palestinian victims of sexual torture by Israeli authorities | 77 | Data on 77 cases from Public Committee Against Torture in Israel database. 15% of victims were minors. They describe beating of the genitals, forced confession, threats of rape, and threats of sexual violence against family members. |

Fig 3. Summary of principal findings reported in the literature.

Direct health effects

Children exposed to armed conflict suffer a broad range of injuries and illness that can be directly attributed to conflict (Fig 3). One third (N = 52) of included studies describe a range of physical injuries affecting all organ systems, broadly classified as penetrating injuries, blunt trauma, crush injuries and burns. Injuries were attributed to shelling, explosions, collapsing buildings, gunshots, and motor vehicle crashes.

Among injured children who reach health facilities, penetrating injuries are most common.[25–39] Penetrating head injury is the most frequent form of head injury among children treated in military combat facilities, accounting for 60–75% of all head injuries and carrying the highest mortality risk.[28, 30, 32] This pattern of head trauma differs markedly from that observed in peaceful settings, where blunt head trauma predominates. It is important to note that the admission criteria for combat support hospitals, access to military facility care, and care seeking behaviours of people living in combat zones are likely to influence the findings in military studies; Spinella et al documented that a child with a severe head injury had sought care at five other hospitals before presenting to a military facility.[40]

Reported mortality from trauma ranges from 2.6–18%,[33–44] and as high as 24% in neurosurgical patients.[30–32, 45] Younger trauma patients bear a significantly higher burden of mortality when compared with older children and adults.[40, 41] No studies provided data on mortality after transfer or discharge from health facilities.

While numerous case studies report children with traumatic amputations, only one study examined the prevalence of disability among war-injured children. This single facility retrospective chart review of 94 children with war-related injuries sustained during the wars in Croatia and Bosnian and Herzegovina found that nearly 40% of the children suffered permanent disability.[43] No studies describe the incidence or prevalence of childhood disability associated with armed conflict or its long term effects on health, development, or life opportunities.

Two studies document the effects of chemical or biological weapons on children. Momeni and colleagues describe the clinical manifestations of mustard gas exposure in a group of children during the Iran-Iraq war.[46] The paper highlights the difference in presentation when compared with adults, including earlier onset of symptoms, more frequent pulmonary and gastrointestinal symptoms, and predominant face and neck symptoms. Guha-Sapir and colleagues found that children in the ongoing conflict in Syria are twice as likely to die from chemical weapon attacks as adults (OR 2.11, 95% CI: 1.69–2.63).[47]

Studies documenting the torture of children report a variety of torture methods that children experienced and/or witnessed. These children suffer physical injuries, a variety of somatic complaints, enuresis, constipation, sleep disorders, and psychological disorders.[47–56] A follow-up study on children who were tortured or whose parents were tortured in Chile found that both the prevalence and frequency of somatic symptoms increased over time after resettlement in Denmark.[55]

Indirect health effects

Diseases

Exposure to armed conflict is associated with a higher burden of infectious, communicable, and noncommunicable diseases in children. A global study of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) associated with civil war found significantly reduced DALYs in children under 14 years for all disease categories, with the most severe reductions in the under 5 (U5) age group.[57] Diseases such as malaria,[58] diarrhoea, acute respiratory infections, and fever[59] are more common and carry higher mortality.[60] A nationwide cross-sectional study in Iraq after the first Persian Gulf War found that age-adjusted mortality due to diarrhoea rose from 2.1 pre-war to 11.9 per 1000 person-years after onset of war.[60] Pregnancy and birth in conflict zones are also higher risk. A study in Tuzla Canton, Bosnia, found significantly fewer live births, increased preterm delivery, and low birth weight during wartime, which normalised again after the war.[61] Displacement due to conflict is associated with crowding, limited access to water and sanitation, and increased risk of infectious and communicable diseases.[62–65]

Environmental exposures

Studies on the effects of combat-related environmental exposures have identified an increased prevalence of birth defects and cancer, as well as ongoing risk of injury due to unexploded ordnance (UXO). The incidence of structural heart defects in Kuwaiti infants rose significantly after the first Persian Gulf War to levels exceeding the international incidence.[66] While the mechanism for this jump in prevalence cannot be identified by the study design, the authors suggest that war-related environmental pollution may play a role. This hypothesis is supported by a large study of birth defects in children of US Gulf War Veterans using active case ascertainment.[67] Conversely, an earlier review of military health records suggests no increased incidence of birth defects among the infants of US Gulf War Veterans.[68]

A study in Iraq found a significantly increased rate of leukaemia, particularly amongst younger children.[69] Similarly, Wen and colleagues found significantly increased risk of AML in children whose fathers reported having served in Vietnam or Cambodia.[70] AML risk was further elevated if fathers reported two or more tours.

Landmines and unexploded ordinance (UXO) remain a significant risk for children during conflict and long after combat has ended.[71–80] The burden of injury due to UXO varies by conflict, however children account for approximately half (42–55%) of injuries from UXO in Afghanistan, Nepal, Eritrea, and Iran.[71, 73, 74, 77, 80] The pattern of injuries in children is similar across settings; children more often suffer upper body injuries sustained while playing, going to school, or tending animals.[71–74, 78, 79]

Access to basic needs

Whilst the burden of disease increases due to conflict, access to health care becomes more difficult. Children in areas affected by conflict are less likely to receive vaccinations [81, 82] and conflicts may contribute to outbreaks of vaccine preventable diseases such as the polio outbreaks during the conflicts in Nigeria and Angola [83, 84] and a rubella outbreak in Bosnia and Herzegovina after hostilities had ended.[85] Combat may also hamper vaccination campaigns during disease outbreaks.[84] Several studies have reported that pregnant women displaced due to war were less likely to receive prenatal care or deliver with the assistance of a skilled birth attendant.[61, 82, 86, 87] Studies from the former Yugoslavia describe drastic reductions in the number of health personnel [88] and conditions where children with chronic conditions had less frequent access to medical care and experienced worsening of their condition.[89]

Conflict also prevents children from going to school and lowers their overall educational attainment. A large time-series cross-sectional study examining the impact of war in sub-Saharan Africa (1950–2010) found that armed conflict significantly reduced school attendance for both boys and girls, and with an inverse correlation between military expenditure and school attendance.[90] Similar findings have also been described in Palestine,[91] Tajikistan[92] and Colombia.[93] The Colombian study findings suggested this may have a long-term effect—adults in areas affected by conflict had lower educational outcomes.

Risk of abuse, neglect, and exposure to secondary violence

Children whose caregivers have been exposed to armed conflict are at increased risk for child abuse and neglect. Studies from Timor-l’Este, Uganda, and in Syrian refugees in Lebanon found that caregivers who suffer from stress or have a mental health disorder related to their exposure to armed conflict have higher rates of child-reported and caregiver-reported child abuse.[87, 94, 95] The Ugandan study findings suggest that war exposure and subsequent trauma are mediating factors for violence against children. Studies among U.S. military personnel have documented increased rates of physical abuse and neglect in the children of veterans, both during the period of deployment and after return.[96, 97] A large study of Californian children in civilian public schools found that the children of US military personnel have higher rates of experiencing violence in school and are more likely to carry a weapon.[98]

Social changes

Important changes in societal structure, norms, and roles take place in populations affected by conflict. Children may assume adult responsibilities, including providing for their families and caring for ill or disabled parents.[99–101] Several studies described changes in sexual behaviour, with earlier sexual debut and child marriage.[102–105] Displacement and separation from family may place children at increased risk for exploitation, high risk sexual behaviour, sexually-transmitted illness, and teen pregnancy.[104] Two studies from Uganda describe particular barriers in access to information and health care for adolescents that further compound their health risks.[104, 105]

Toxic stress and child development

While numerous studies document the multiple kinds of war-related violence that children witness, no studies examine the effect of these exposures on child motor and psychosocial development. Two studies examined the influence of war-related trauma on children’s stress physiology. Feldman et al. found that war-exposed children had altered cortisol and salivary amylase response to stress.[106] The same study also found that children’s baseline cortisol levels were independently related to maternal baseline cortisol, mother-child relationship, and maternal mental health. Similarly, the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study described altered stress physiology in children who were separated from their parents for a period during WWII.[107] Two other studies on the same birth cohort found that separated girls had significantly earlier onset of menarche than non-separated girls, and that children separated from their parents in early childhood had lower scores on intelligence testing, respectively.[108, 109]

Children associated with armed forces or armed groups (“child soldiers”)