Abstract

Microparticles are a newly recognized class of mediators in the pathophysiology of lung inflammation and injury, but little is known about the factors that regulate their accumulation and clearance. The primary objective of our study was to determine whether alveolar macrophages engulf microparticles and to elucidate the mechanisms by which this occurs. Alveolar microparticles were quantified in bronchoalveolar fluid of mice with lung injury induced by LPS and hydrochloric acid. Microparticle numbers were greatest at the peak of inflammation and declined as inflammation resolved. Isolated, fluorescently labeled particles were placed in culture with macrophages to evaluate ingestion in the presence of endocytosis inhibitors. Ingestion was blocked with cytochalasin D and wortmannin, consistent with a phagocytic process. In separate experiments, mice were treated intratracheally with labeled microparticles, and their uptake was assessed though microscopy and flow cytometry. Resident alveolar macrophages, not recruited macrophages, were the primary cell-ingesting microparticles in the alveolus during lung injury. In vitro, microparticles promoted inflammatory signaling in LPS primed epithelial cells, signifying the importance of microparticle clearance in resolving lung injury. Microparticles were found to have phosphatidylserine exposed on their surfaces. Accordingly, we measured expression of phosphatidylserine receptors on macrophages and found high expression of MerTK and Axl in the resident macrophage population. Endocytosis of microparticles was markedly reduced in MerTK-deficient macrophages in vitro and in vivo. In conclusion, microparticles are released during acute lung injury and peak in number at the height of inflammation. Resident alveolar macrophages efficiently clear these microparticles through MerTK-mediated phagocytosis.

Keywords: microparticle, phagocytosis, alveolar macrophage, lung injury, Mer tyrosine kinase

INTRODUCTION

Inflammation is a major component of many acute and chronic lung diseases. Although often beneficial, inflammation can also drive tissue injury. Accordingly, for organ recovery to occur, inflammation must be resolved. The mechanisms that regulate resolution in the lung are highly complex and remain incompletely understood (36, 45). In this context, microparticles are newly described inflammatory mediators that have been documented in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (3), asthma (25), and interstitial lung disease (32) and in the circulation of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (41). Although the roles played by microparticles in these diseases continue to be investigated (26, 31), to our knowledge, no studies have focused on their clearance as it pertains to the resolution of inflammation.

Microparticles comprise a heterogeneous group of small (100-nm to 1-μm diameter) membrane-bound particles that characteristically expose phosphatidylserine (PS) on their outer membrane surface. They can be released from a variety of cells, including epithelial cells, macrophages, neutrophils, platelets, and endothelial cells (11, 26, 43). These varied origins contribute to their heterogeneity, as does their cargo, which can include membrane and cytosolic proteins, cytokines, and RNA derived from the parent cell. Microparticles serve as vehicles for intercellular communication through a variety of mechanisms, including transfer of their contents to target cells, receptor-mediated signaling, and the release of soluble signaling molecules (11, 40). Although there has been recent work evaluating the function of microparticles in acute lung injury models (5, 21, 39), there has been no work aimed at understanding their fate. Given the emerging evidence that microparticles are involved in the pathophysiology of acute lung injury, we sought to characterize their rate of accumulation and determine the mechanisms that regulate their clearance from the alveolus during an acute inflammatory response.

As the primary phagocyte in the lung, the alveolar macrophage is tasked with removing particles and pathogens. During inflammation the macrophage pool expands, fueled both by local proliferation of resident macrophages and recruitment of monocytes from the circulation that mature into “recruited” macrophages (14, 33). These different macrophage subsets appear to have distinct programming and functions (1, 45). Whereas the resident alveolar macrophages are often viewed as sentinels that respond to danger signals and initiate the inflammatory cascade, it is the newly recruited macrophages that primarily facilitate the removal of apoptotic inflammatory cells during resolution of inflammation (15, 22). We have shown previously that recruited alveolar macrophages efficiently clear apoptotic cells (15), however it remains unknown whether they also engulf microparticles. Moreover, the mechanisms that drive the potential engulfment of microparticles have not been studied. We hypothesized that recruited alveolar macrophages efficiently clear microparticles during the resolution of lung injury and that the underlying mechanisms that control engulfment of apoptotic cells and microparticles would be the same.

Macrophages engulf particles via endocytosis, the active transport of particles into the cell by invagination of the cell membrane. There are two independent mechanisms of endocytosis of large particles (>100 nm): phagocytosis and macropinocytosis. Both forms of endocytosis are receptor mediated and require actin-dependent rearrangement of the cytoskeleton. However, the mechanics of engulfment are different. Phagocytosis involves a zipper-like mechanism in which pseudopods wrap closely around the target, excluding surrounding fluid. In comparison, macropinocytosis uses cell membrane ruffles that protrude around a target, fold back onto the membrane, and fuse, forming large endocytic macropinosomes. This allows cells to sample and internalize extracellular fluid, along with the target (17, 23). Receptors involved in engulfment (efferocytosis) of apoptotic cells (20, 37) include the TAM (Tyro3, Axl, and Mer) family of receptor tyrosine kinases. In this context, PS exposed on the surface of apoptotic cells is bound by the soluble proteins Gas6 or protein S, which are then recognized by TAMs (34, 37). Mer tyrosine kinase (MerTK) and Axl are highly expressed by alveolar macrophages (9, 18). Since these receptors drive ingestion of apoptotic cells, we hypothesized that MerTK and Axl are also required for optimal uptake of microparticles by alveolar macrophages.

In this study, we show that proinflammatory microparticles accumulate in the airspaces of mice with acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or hydrochloric acid (HCl). We further show that resident alveolar macrophages, rather than recruited macrophages, are the key phagocytes responsible for microparticle clearance and that MerTK expressed on the macrophage surface mediates microparticle removal.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

C57BL/6, GFP ubiquitin reporter [C57BL/6-Tg(UBC-GFP)30Scha/J], MerTK−/− (B6;129-Mertktm1Grl/J), and B6.129 mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Adult (8–14 wk old) male mice were used for all experiments. All animals were housed in a licensed animal care facility on the National Jewish campus. This study was approved by and performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at National Jewish Health, Denver, CO.

Lung injury model and measurement of cells and alveolar microparticles.

C57BL/6 mice were treated with either 20 μg LPS (Escherichia coli O55:B5 from List Biological Laboratories, Campbell, CA) or 40 μl of hydrochloric acid (0.1N, pH 1.3) via intratracheal instillation using a modified feeding needle while under light sedation with isoflurane (Baxter, Deerfield, IL). Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed as described previously (16). Cell counts and differentials were performed on the lavage specimens. Cell differentials were determined using Diff-Quik-stained cytospin specimens. Cell counts were performed using a Coulter Counter. Microparticles present in the BAL were quantified using flow cytometry and LSR II (Becton-Dickinson), using a wide-angle forward scatter aperture. Fluorescent microbeads (Megamix beads, Biocytex, France) were used for size measurement and counting of particles. Microparticles were defined as particles 1 μm or smaller in diameter. Data were analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR.).

Isolation of alveolar microparticles.

BAL was performed on untreated (C57BL/6) or acid-treated mice at 24 h. The BAL was centrifuged at 200 g for 10 min to pellet whole cells. Microparticles were maintained in the fluid phase, which was aspirated and subjected to a second centrifuge step at 10,000 g for 10 min. The pellet from this step constitutes the alveolar microparticles, which were then washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before further analysis or labeling.

Electron microscopy of alveolar microparticles.

Microparticles were obtained from mice with HCl-induced lung injury 24 h following onset of injury, as described above. Microparticles were washed twice in PBS and then fixed with glutaraldehyde. Electron microscopy was performed on a Philips 400T transmission electron microscope (Holland) by the Pathology Laboratory Core Facility at National Jewish Health.

Antibodies and fluorescent labels.

PKH67 membrane label (Sigma), Cellvue Maroon membrane label (eBioscience), FITC-labeled Dextran (Molecular Probes), and pHRODO red (Life Technologies) were used for in vitro uptake experiments. Membrane labels were applied according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Anti-CD11c (clone N418; eBioscience), anti-CD64 (clone X54-5/7.1; BD PharMingen), anti-CD11b (clone M1/70; eBioscience,), anti-F4/80 (clone BM8; eBioscience), anti-Ly6G (clone 1A8; BD Biosciences), anti-MerTK biotinylated (BAF591; R & D Systems), streptavidin (Jackson Immunoresearch), and anti-Axl (FAB8541; R & D Systems) were used for cell surface marker expression. All flow cytometry antibodies were diluted to a concentration of 1:200, except for MerTK and Axl, which were used at 1:100. For Western blots, anti-Gas6 (AF986; R & D Systems) and anti-Protein S (clone 818002; R & D Systems) primaries were used at 1:1,000 and 1:200, respectively; donkey anti-rat and anti-goat Cy3 secondaries (Jackson Immunoresearch) were used at 1:200.

Zymosan-induced peritonitis and culture of macrophages.

Peritonitis was induced by intraperitoneal injection of 1 ml of zymosan (1 mg/ml; Life Technologies). On day 4 postinjection, peritoneal lavages were performed with 10 ml of ice-cold HBSS (without Ca2+ or Mg++) containing 1 mM EDTA and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.2). Cells were then plated on sterile microscope slides (12 mm) at 50,000 cells/slide and allowed to adhere for 2 h, at which time they were washed once with media before treatment.

Isolation and culture of alveolar macrophages.

Resident alveolar macrophages were obtained from naïve mice by performing BAL with 10 ml of PBS supplemented with 5 mM EDTA following euthanasia. Lavage fluid was centrifuged at 500 g for 5 min. Cells were washed once with DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (ThermoFischer Scientific, Waltham, MA), penicillin, streptomycin, and glutamine (Sigma). For microscopy experiments, cells were then plated on sterile microscope slides (12 mm) at 50,000 cells/slide and allowed to adhere for 2 h, at which time they were washed once with media before treatment. For stimulation assays, macrophages were plated at 250,000 cells/well in 24-well plates.

MLE-12 cell culture.

MLE-12 (ATCC) cells were cultured with DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, penicillin, streptomycin, and glutamine. Cells were plated at 500,000 cells/well in 12-well plates. Cells were serum starved overnight before stimulation the following day.

In vitro endocytosis assays.

Plated cells were treated with labeled microparticles obtained from acid-injured mice. The microparticles were placed in coculture with the cells for 2 h. Following incubation, the cells were washed three times with media and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Cells were then washed with PBS four times before mounting with Vectashield containing DAPI (Vector). In separate experiments, cells were pretreated for 2 h with 2 μM cytochalasin D (Sigma), 0.1 mM amiloride (Sigma), 10 nM wortmannin (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), or 200 nM Axl inhibitor TP-0903 (Selleckchem, Houston, TX). Cells were viewed using confocal microscopy using Zeiss LSM 700. Fluorescent 2-μm latex beads (Sigma) were used as positive control for endocytosis.

Determination and calculation of pixel index.

Micrographs were analyzed using CellProfiler (version 2.1.1) to calculate the number of pixels corresponding to PKH, CellVue Maroon, or pHRODO-labeled microparticles. Micrographs were first converted to separate grayscale images of red, green, and blue components using the ColorToGray module. Nuclei (used as a surrogate for the number of macrophages) were identified by analyzing the grayscale blue component image with the IdentifyPrimaryObjects module utilizing the following parameters: 1) diameter and threshold ranges were determined by measuring diameter and intensity of macrophage nuclei from 200 micrographs; 2) any objects outside of the diameter range or touching the border of the image were discarded; and 3) manual threshold as determined above and shape were used to distinguish between any clumped nuclei. Although washing removed any non-macrophage-associated microparticles, masking was applied to the microparticle’s image before processing to assess the number of pixels only in areas occupied by macrophages. For determining the number of microparticle-corresponding pixels, the following parameters were used: 1) threshold values were determined by measuring intensity of autofluorescence from 200 control micrographs; 2) the ApplyThreshold module was used to generate a binary (black and white) image from the red or green component grayscale image generated from the ColorToGray module; and 3) the MeasureImageAreaOccupied module was used to calculate the number of pixels from the thresholded binary image. Pixel index was calculated as total pixels per high-power field divided by number of cells in field.

Cell stimulation assay and PCR analysis.

MLE-12 cells and resident alveolar macrophages were plated as described. Cells were treated with LPS (100 ng/ml), microparticles, or LPS and microparticles. Cells were then cultured for 4 h and then washed with PBS. The cells were lysed, and RNA was isolated via the Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands) per the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was generated using Superscript Vilo IV (ThermoFischer Scientific). PCR was performed using PowerUp SYBR Green Mastermix (Applied Biosystems, Austin, TX) with a C1000 Thermal Cycler and CFX96 Real Time System (Bio-Rad). Primer sets were as follows: GAPDH, forward AACGACCCCTTCATTGAC and reverse TCCACGACATACTCAGCAC; KC, forward GCCTATCGCCAATGAGCTG and reverse CTGAACCAAGGGAGCTTCAGG; TNFα, forward CATCTTCTCAAAATTCGAGTGACAA and reverse TGGGAGTAGACAAGGTACAACCC; IL-6, forward GAGGATACCACTCCCAACAGACC and reverse AAGTGCATCATCGTTGTTCATACA.

Lipid extraction and mass spectrometry.

Microparticle pellets from either naïve or acid-treated mice were isolated as above, and lipids were extracted in methanol and analyzed by liquid chromatography-mass sprectrometry/mass sprectrometry (LC-MS/MS) by monitoring neutral loss of 87 atomic mass units in negative ion mode, as previously described (8).

Macrophage cell sorting and RNA isolation.

For RNA sequencing experiments, macrophages were isolated using FACS. On days 0, 3, and 6 following LPS-induced injury, mice underwent BAL with 10 serial lavages of 1 ml of PBS containing 5 mM EDTA. Cells from BAL were washed twice and resuspended in PBS. Samples from five to 10 animals at each time point were pooled, and red blood cells were lysed using BD PharmLyse lysis buffer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Cells were washed twice in PBS before FcyR blocking. Cells were incubated with 1 μg of primary antibody on ice for 30 min, washed twice, and then taken to FACS. Dead cells were excluded on the basis of scatter and DAPI exclusion. Neutrophils were excluded using Ly6G and macrophages identified using F4/80 and CD64. Resident macrophages were identified as CD11chigh, CD11blow/mid, and Siglec-Fhi. Recruited macrophages were identified as CD11clow, CD11bhigh, and Siglec-Flow. Cell sorting was performed using a Moflo XDP-100 (Beckman Coulter). Sorts were performed in triplicate, and at least 300,000 total cells were collected per population at each time point. Purified cells were pelleted, and RNA was prepared using Qiagen RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen Sciences, Valencia, CA) per the manufacturer’s protocol.

cDNA generation and microarray.

Isolated total RNA was processed in the NJH Genomics Facility for next-generation sequencing (NGS) library construction, as developed for analysis with a Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA) Ion Proton NGS platform. A modified Kapa Biosystems (Wilmington, MA) KAPA Stranded mRNA-Seq kit for whole transcriptome libraries was used primarily to target all polyA RNA. Libraries were sequenced as barcoded-pooled samples on a P1 Ion Proton chip, as routinely performed by the NJH Genomics Facility. Data are available at GEO accession no. GSE94749. Transcripts per million of the selected genes were analyzed and displayed using the Morpheus web-based tool (Broad Institute).

Western immunoblot analysis.

Microparticles were isolated from mice as described above. The particles were then washed with PBS and placed in RIPA lysis buffer. Samples were boiled for 5 min after the addition of Laemmli electrophoresis sample buffer, and then proteins were separated on 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). To compare amounts of the proteins in microparticles between naïve and injured animals, the volume loaded into each well was the equivalent of one-quarter of BAL volume from each animal. The blots were then transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, which were then blocked for 1 h in LI-COR (Lincoln, NE) blocking buffer and then incubated overnight with Gas6 or Protein S antibody at 4°C. The membranes were washed and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h. Detection was performed using the Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP Imaging system.

In vivo microparticle endocytosis assays.

Alveolar microparticles were obtained from HCl-treated C57BL/6 mice and labeled with PKH. PKH-labeled microparticles were then intratracheally instilled into C57BL/6 mice that had been treated with LPS 3 days prior. This allowed us to achieve a mixed macrophage population in the lungs on which to assess microparticle uptake (14). One hour following instillation, animals were euthanized and BAL was performed. Samples were then analyzed using flow cytometry or confocal microscopy (Zeiss LSM 700) to assess uptake of PKH-labeled microparticles into lavaged cells. Mean fluorescence intensity was measured via flow cytometry and calculated by subtracting the geometric mean of background fluorescence from the geometric mean of the sample. In separate experiments, naïve B6.129 or MerTK−/− mice were used as recipients.

Statistical analyses.

Data are presented as means ± SE and include at least three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 7 software. Student’s t-test (for normally distributed data) or Wilcoxon test (for non-normal data or small sample sizes) were performed for two sample tests. One-way ANOVA or Friedman’s test with multiple comparisons was performed where two or more variables were evaluated. Differences with P < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Kinetics of microparticle accumulation and clearance during lung injury.

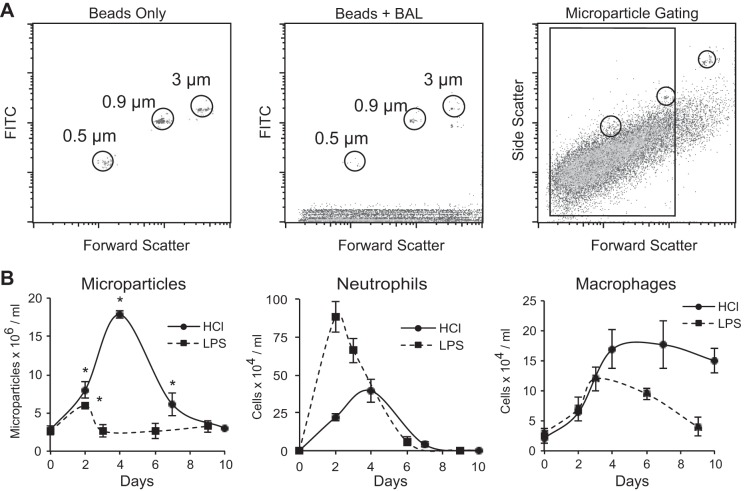

Microparticles are released into the alveolus during acute lung injury in mice and humans (3, 26, 39). As an initial step toward characterizing how microparticles accumulate and are cleared, microparticle concentrations were quantified in the airspaces following intratracheal instillation of either LPS or hydrochloric acid. At serial time points after the onset of inflammation, BAL was performed, leukocytes were counted, and differential cell counts were performed. Alveolar microparticles were quantified in aliquots of undiluted BAL fluid spiked with size-calibrated fluorescent microbeads using flow cytometry (Fig. 1A). Microparticles were defined as particles between 100 nm and 1 μm in diameter. As shown in Fig. 1B, instillation of both hydrochloric acid and LPS resulted in marked inflammation with neutrophil and macrophage recruitment into the alveolar space. Microparticle accumulation temporally correlated with the accumulation of neutrophils in both models; however, microparticle levels were significantly higher in acid-treated mice. Notably, the amount of microparticles decreased as the number of macrophages increased, supporting the hypothesized role for macrophages in microparticle clearance.

Fig. 1.

Microparticles accumulate in the alveolus during acute lung injury. A: flow cytometry gating strategy showing initial gating on size-calibrated FITC fluorescent microbeads and microparticles from bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). B: C57BL/6 mice were treated with either lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 20 μg) or hydrochloric acid (1 N, pH 1.1) via intratracheal instillation. BAL was performed at serial time points. Cell counts and differentials were performed on the lavage specimens. Microparticles present in the BAL were quantified using flow cytometry and a known quantity of microbeads; each value represents means ± SE (n = 5). *P < 0.05 for microparticles compared with naïve mice.

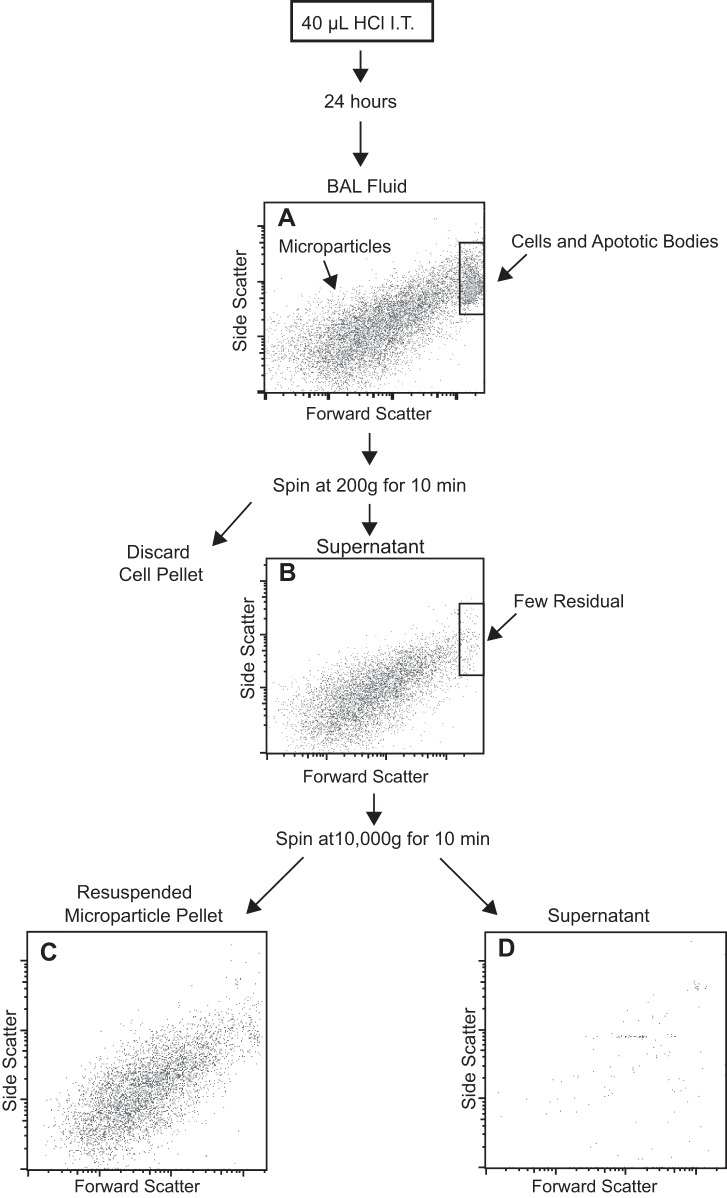

Isolation of alveolar microparticles during acute lung injury.

To further characterize the microparticles, we developed methods to isolate them from BAL fluid. The acid model of lung injury was used since this model produced more particles and did not carry the potential to transfer LPS along with the microparticles. Because microparticles are smaller than whole cells and apoptotic bodies, we used serial centrifugation for their separation (Fig. 2). First, low-speed centrifugation (200 g) was used to pellet cells. The cell-free supernatant was then removed and centrifuged at a higher speed (10,000 g) to pellet microparticles. This approach was validated by performing flow cytometry on the isolated microparticles, which confirmed that intact and apoptotic cells were almost completely removed and that the majority of the purified microparticles were smaller than 1 μm in diameter. Notably, the isolation was highly efficient; very few microparticles were present in the supernatant following the final centrifugation step.

Fig. 2.

Microparticle purification using serial centrifugation. BAL was performed on HCl acid-treated mice at 24 h. A: whole BAL before centrifugation. Microparticles and cells are present. B: supernatant after BAL was centrifuged at 200 g for 10 min to pellet cells. Cells are no longer present; remaining events are microparticles predominantly below 1 μm in diameter. A second centrifuge step was performed at 10,000 g for 10 min to pellet microparticles. C: resuspended pellet demonstrates that microparticles are contained in this fraction. D: supernatant remaining after the second centrifugation step. No microparticles are present. IT, intratracheal.

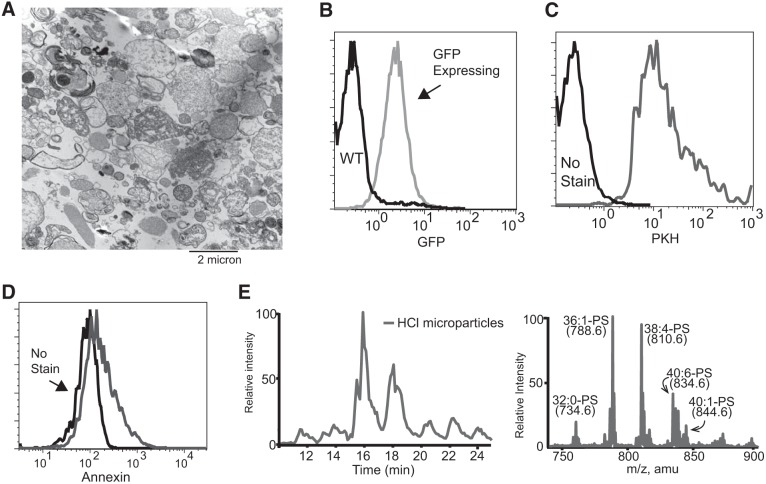

Characterization of microparticles confirms phosphatidylserine exposure on outer membrane.

We next sought to characterize the particles that were isolated from HCl-treated mice. Ultrastructural evaluation (Fig. 3A) revealed membrane-bound particles and further verified their small and heterogeneous size as seen by flow cytometry. To verify that the microparticles were cell-derived and had intact membranes, we used reporter mice, in which green fluorescent protein (GFP) is produced under control of the ubiquitin promoter and remains in the cytoplasm (38). Notably, GFP expression is lost if the cell membrane is permeabilized. Microparticles isolated from acid-injured animals were assessed using flow cytometry and were found to be uniformly GFP positive (Fig. 3B), suggesting that they contained cell cytoplasm, had intact plasma membranes, and were not simply alveolar surfactant or acellular particulates. To further confirm that the microparticles had an outer lipid membrane, fluorescent PKH membrane labeling dye was added. As anticipated, the microparticles stained uniformly positive (Fig. 3C). Similar results were observed with lipophilic CellVue Maroon dye (not shown). In healthy cells, PS is confined to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane; however, when microparticles are released, membrane asymmetry is lost and PS exposed. Annexin V staining (Fig. 3D) showed that a significant proportion of the microparticles expressed PS. We further verified the presence of PS in the microparticles by performing mass spectrometry on lipid extracted from microparticle pellets. A variety of diacyl-phosphatidylserine species were enriched in the pellet (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

Microparticle characterization. A: microparticles isolated from HCl-treated mice were fixed and imaged using electron microscopy. B: representative flow cytometry of microparticles isolated from green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing mice (gray line) and wild-type (WT) mice (black line) treated with HCl. C: microparticles either stained with PKH (gray line) for lipid membranes or unstained (black line). D: microparticles either stained with annexin V (gray line) or unstained (black line). E: diacyl-phosphatidylserine (PS) is enriched in microparticles from HCl-treated mice. Left: total ion chromatography from 10 to 25 min from the liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry chromatogram of diacyl-PS. Right: corresponding total ion mass spectrum of diacyl-PS monitoring neutral loss of 87 atomic mass units in negative ion mode.

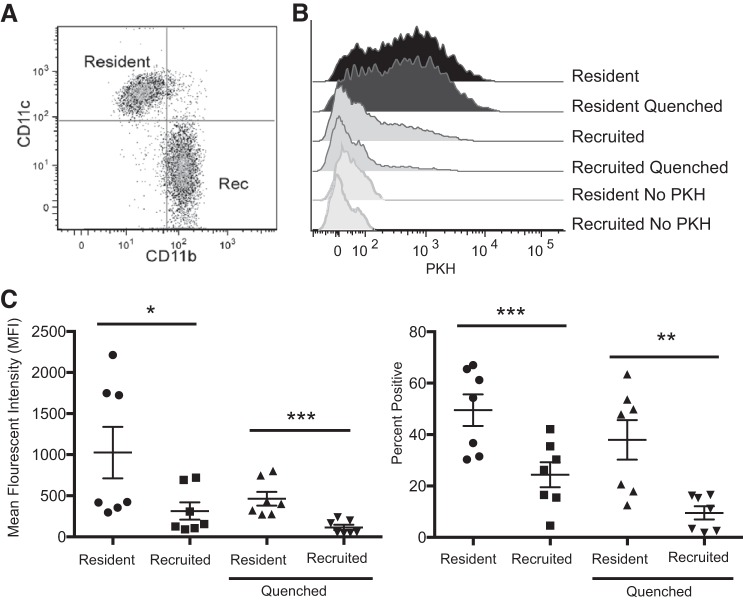

Alveolar microparticles are endocytosed by resident alveolar macrophages during inflammation.

During inflammation, two distinct macrophage populations are present in the alveolus: resident alveolar macrophages that arise during embryogenesis and self-replicate throughout life and recruited macrophages that derive from circulating monocytes and mature into macrophages during inflammation. Both cell types are capable of endocytosing microbial pathogens, inert particles, and apoptotic cells; however, their ability to ingest these targets differs. We have shown previously that recruited macrophages are able to ingest apoptotic cells more avidly than resident macrophages (15). To address the cellular selectivity of microparticle uptake, microparticles were labeled with fluorescent PKH and intratracheally administered to recipient mice that had been pretreated with intratracheal LPS 3 days prior (to induce the accumulation of recruited macrophages). BAL was performed 1 h following instillation and analyzed using flow cytometry to assess PKH-labeled microparticle uptake. Macrophages were identified with F4/80 and CD64, and then resident and recruited macrophage subsets were gated based on their characteristic expression of CD11c vs. CD11b (Fig. 4A) (14). To distinguish microparticles bound to the macrophage surface from those that had been engulfed, trypan blue was added to paired aliquots of cells to quench extracellular PKH fluorescence. Resident alveolar macrophages had significantly greater association with microparticles (no quenching) and endocytosed significantly more microparticles (assessed after quenching) than recruited macrophages isolated from the same lungs (Fig. 4, B and C). This was counter to our previous apoptotic cell clearance data (15) and suggests the two different macrophage subsets have specificity for different particle types.

Fig. 4.

Microparticles are engulfed by resident alveolar macrophages during acute lung injury. A: dating strategy to isolate resident and recruited (Rec) alveolar macrophages in BAL fluid. BAL macrophages were identified as CD45+, F4/80+, Ly6G negative, and CD64+ and then classified as shown into resident (CD11chi, CD11blo) or Rec (CD11bhi, CD11clo) macrophages. B: PKH-labeled microparticles were instilled into LPS-treated mice. BAL was performed 1 h later, and macrophages were assessed for PKH intensity. Immediately after initial analysis, cells were quenched with trypan blue to eliminate fluorescence of bound but not internalized microparticles. C: microparticle uptake quantified using mean fluorescence intensity (left) and %macrophages ingesting microparticles (right); n = 7. Data represent means ± SE. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Microparticle engulfment by macrophages occurs via phagocytosis.

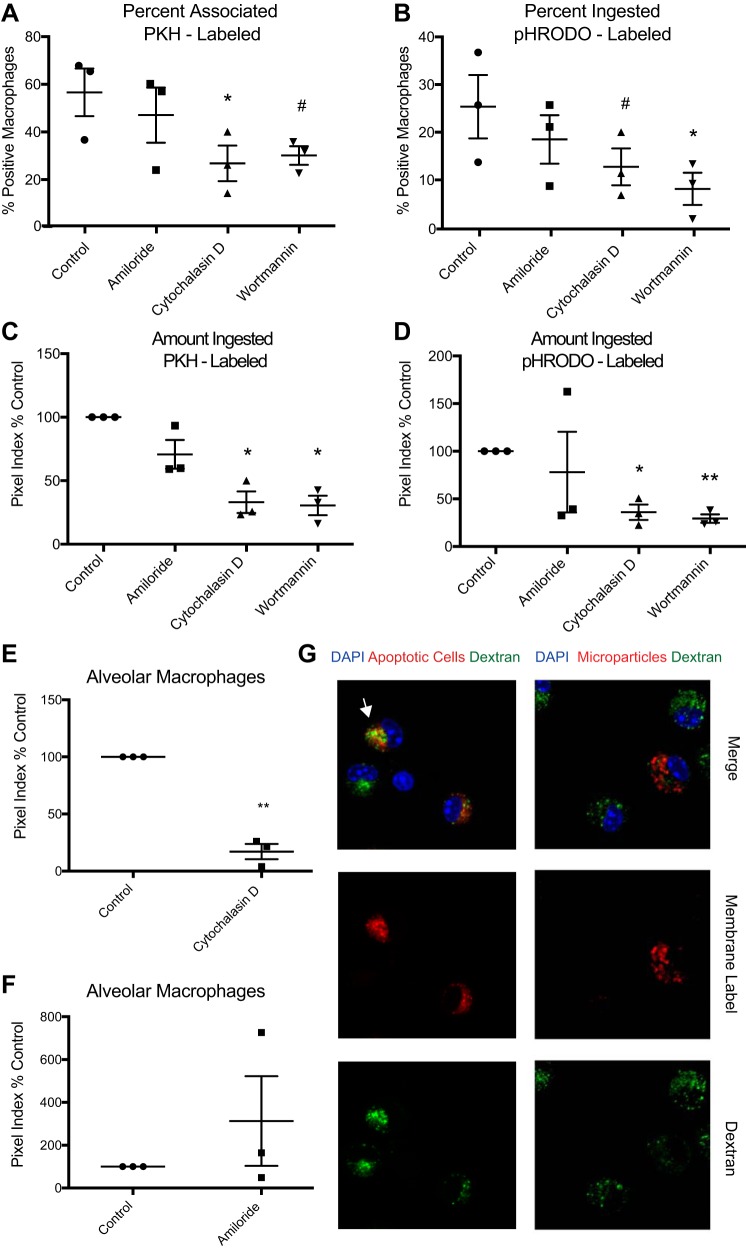

We next sought to determine the mechanisms used by macrophages to endocytose microparticles. As a first step, confocal microscopy was used to quantify engulfment of microparticles by macrophages in the presence of endocytosis inhibitors (or vehicle control). Peritoneal macrophages obtained from mice with zymosan-induced peritonitis were used since this yields very high numbers of cells from an inflammatory environment. As with previous experiments, alveolar microparticles were isolated from acid-injured mice and stained with the membrane label PKH or pHRODO, a pH-sensitive compound that fluoresces upon acidification in a lysosome. The microparticles were then added to cell cultures with selected endocytosis inhibitors (or vehicle control). Engulfment was assessed using fluorescent microscopy. Because macrophages ingest apoptotic cells using macropinocytosis (13), we hypothesized that this would be the dominant mechanism of microparticle engulfment. In this context, cytochalasin D, an inhibitor of actin polymerization required for most forms of endocytosis (including phagocytosis and macropinocytosis), and wortmannin, a PI 3-kinase inhibitor also implicated in various forms of endocytosis, suppressed microparticle uptake (Fig. 5, A and B). Notably, amiloride, a selective inhibitor of macropinocytosis, had no effect.

Fig. 5.

Microparticles are phagocytosed by macrophages in vitro. Peritoneal macrophages were cultured with fluorescently labeled microparticles in the presence of endocytosis inhibitors. A: %macrophages associated with PKH-labeled microparticles. Uptake quantified by confocal microscopy. B: %macrophages engulfing pHRODO-labeled microparticles. C and D: magnitude of engulfment of PKH-labeled (C) and pHRODO-labeled (D) microparticles. Fluorescent pixels per macrophage were calculated (pixel index) and normalized to WT control. Data are expressed as %control. E: endocytosis of PKH-labeled microparticles by resident alveolar macrophages with or without cytochalasin D. Engulfment assessed after 1 h by confocal microscopy. F: membrane-labeled (cellvue maroon) microparticles or apoptotic thymocytes (positive control for macropinocytosis) and FITC-labeled dextran were added in coculture with resident alveolar macrophages. Dextran colocalizes with apoptotic cells (white arrow) but not microparticles. G: membrane-labeled microparticles or apoptotic cells were added in coculture with resident alveolar macrophages in the presence of amiloride. Data represent means ± SE; n = 3 independent experiments. #P < 0.1; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Symbols are replicates in the following groups: ●, control; ■, amiloride; ▲, cytochalasin; ▼, wortmannin.

To objectively gauge the burden of microparticles ingested by each macrophage, we calculated a pixel index, defined as the number of fluorescently positive pixels contained within each macrophage in a high-power field divided by the total number of macrophages in the field. Cytochalasin D and wortmannin significantly reduced the amount of PKH- and pHRodo-labeled microparticles that were ingested, but again, amiloride had no effect (Fig. 5, C and D), even at the highest dose tested that was not toxic to cells (high dose shown). To verify these findings in alveolar macrophages, resident AMs from BAL of naïve mice were isolated, cultured, and exposed to PKH-labeled microparticles in the presence of cytochalasin D or vehicle control (Fig. 5E). Cytochalasin D again inhibited microparticle uptake. Taken as a whole, these experiments suggest that, counter to our original hypothesis, a form of phagocytosis (rather than classical macropinocytosis) was the dominant uptake mechanism used by macrophages to clear microparticles.

As mentioned previously, phagocytosis involves a zipper-like mechanism in which pseudopods tightly surround the target, resulting in exclusion of neighboring fluid phase components from the phagosome. In contrast, macropinocytosis includes uptake of fluid surrounding the target. Accordingly, to further verify that macrophages ingest microparticles using phagocytosis, we added FITC-labeled dextran to culture media simultaneously with PKH-labeled microparticles. After 1 h, cells were washed to remove any uningested microparticles and fixed. Confocal microscopy was used to determine colocalization of microparticles and dextran. Compared with apoptotic cells that are typically cleared by macropinocytosis, microparticles did not colocalize with the dextran (Fig. 5F). Furthermore, the addition of amiloride did not inhibit the uptake of microparticles by alveolar macrophages (Fig. 5G). This further verified that microparticles are taken up via phagocytosis rather than macropinocytosis.

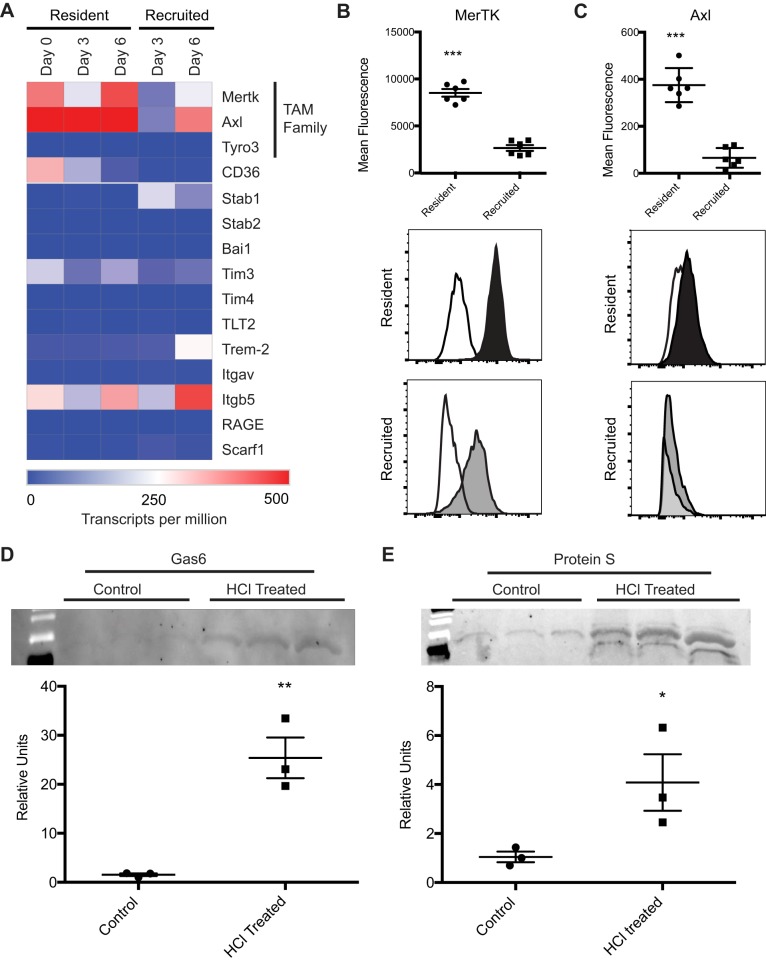

Resident alveolar macrophages possess the endocytic receptors MerTK and Axl.

Phagocytosis is triggered when targets bind to recognition receptors on the surface of the phagocyte. Because microparticles expose PS, we reasoned that receptors that bind or recognize PS, efferocytosis receptors, might be involved. As an initial screen for candidate receptors, we interrogated a database generated by our group in which RNA sequencing was performed on resident alveolar macrophages from naïve mice (day 0) and resident vs. recruited macrophages isolated 3 and 6 days after intratracheal LPS administration (28). As shown in Fig. 6A, the TAM receptors MerTK and Axl were expressed in both resident and recruited macrophages. Expression levels of Tyro3 and other receptors were low, with the exception of integrin subunit 5, which can bind PS via the bridging molecule MFG-E8 (30), which was expressed predominately in the recruited macrophages. To validate the RNA-seq findings at the surface protein level, flow cytometry was performed on alveolar macrophages isolated from LPS-treated mice on day 3 (Fig. 6B). MerTK and Axl were expressed at higher levels on the resident alveolar macrophages compared with the recruited macrophages. Given these findings, along with the observation that resident macrophages are primarily responsible in microparticle uptake (Fig. 4), we hypothesized that MerTK and/or Axl are critical drivers of microparticle recognition and engulfment.

Fig. 6.

Alveolar macrophages express Mer tyrosine kinase (MerTK) and Axl. A: expression of phagocytic receptors in resident and recruited alveolar macrophages following LPS-induced lung injury, as measured with RNA-seq. Gene expression shown as mean transcripts per million; n = 3 experiments. B and C: MerTK (B) and Axl (C) expression on resident (black) and recruited (gray) alveolar macrophages isolated from LPS-treated mice (day 3). White histogram represents fluorescence minus one for MerTK or Axl. D and E: Western blotting for Gas6 and protein S in microparticle pellets isolated from naïve and hydrochloric acid-treated mice. Equivalent volumes of BAL fluid were used to recover microparticles; one-quarter of the total microparticle protein was loaded for each sample. Representative blots are shown with corresponding densitometry. Data represent means ± SE; n = 3. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

The TAM receptors require bridging molecules to bind to PS. Specifically, Gas6 and protein S have been shown to bind PS and facilitate binding to Tyro3, Axl, and MerTK. We sought to determine whether these molecules were present on microparticles, which express PS (as previously shown in Fig. 3). Accordingly, microparticles were isolated from BAL fluid of naïve and acid-treated mice. Western blotting was performed for Gas6 and protein S. Both proteins were detected at high levels in the microparticle lysates from acid-injured mice; lower expression was seen in the microparticle lysates from naïve animals (Fig. 6D). The presence of these two proteins supports the possibility of a TAM receptor-mediated uptake mechanism.

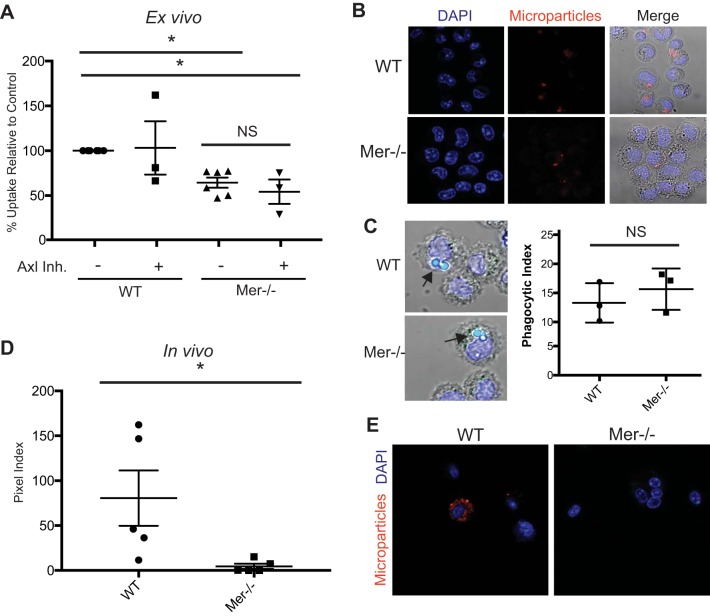

Deletion of MerTK leads to diminished endocytosis of alveolar microparticles.

Because MerTK and Axl were highly expressed on resident alveolar macrophages, we next sought to determine whether these receptors were required for microparticle uptake. Accordingly, resident alveolar macrophages were isolated from naïve MerTK−/− and wild-type (WT) B6.129 mice and cultured with or without the Axl inhibitor TP-0903. The cells were then cocultured with membrane-labeled microparticles, and uptake was measured via confocal microscopy. Macrophages deficient in MerTK ingested fewer microparticles than WT macrophages (Fig. 7, A and B), whereas Axl inhibition did not significantly decrease the uptake. Axl inhibition did not further decrease phagocytosis in MerTK−/− macrophages, pointing toward MerTK being the dominant uptake mechanism. Notably, MerTK−/− macrophages were still able to ingest latex beads effectively (Fig. 7C), demonstrating a microparticle-specific phagocytic defect.

Fig. 7.

MerTK is required for optimal microparticle uptake by alveolar macrophages. A: resident alveolar macrophages from MerTK−/− or B6.129 control mice were cultured on microscope slides with or without an Axl inhibitor. Membrane-labeled microparticles were placed in coculture with the macrophages. One hour later, cells were washed to remove noningested microparticles and then fixed with paraformaldehyde. Fluorescent pixels per macrophage were calculated (pixel index) and normalized to WT controls; n = 3–6. Data represent means ± SE. B: representative images of microparticle endocytosis. C: alveolar macrophages from WT and MerTK−/− mice cultured with 2-μm latex beads (arrows). Endocytosis of beads by MerTK−/− mice is not impaired. D: membrane-labeled microparticles were intratracheally instilled into naïve MerTK−/− and WT. Cytospins were performed on BAL, and endocytosis was quantified with confocal microscopy; n = 5. E: representative images of in vivo microparticle uptake by alveolar macrophages from WT and MerTK−/− mice. *P < 0.05. Symbols are replicates in the following groups: ●, control; ■, amiloride; ▲, cytochalasin; ▼, wortmannin.

Because culturing macrophages can change their programming, we sought to confirm our findings in vivo. Microparticles from acid-treated mice were isolated, fluorescently labeled with PKH, and intratracheally instilled into naïve WT and MerTK-deficient mice. Two hours after instillation, recipient mice underwent BAL. Cells were isolated from BAL fluid by centrifugation and washed twice to eliminate noningested microparticles. Uptake was quantified using confocal microscopy (Fig. 7, D and E). MerTK−/− macrophages took up significantly fewer microparticles than WT macrophages. Taken as a whole, these findings demonstrate that MerTK on resident alveolar macrophages is required for efficient phagocytosis of microparticles during acute lung injury.

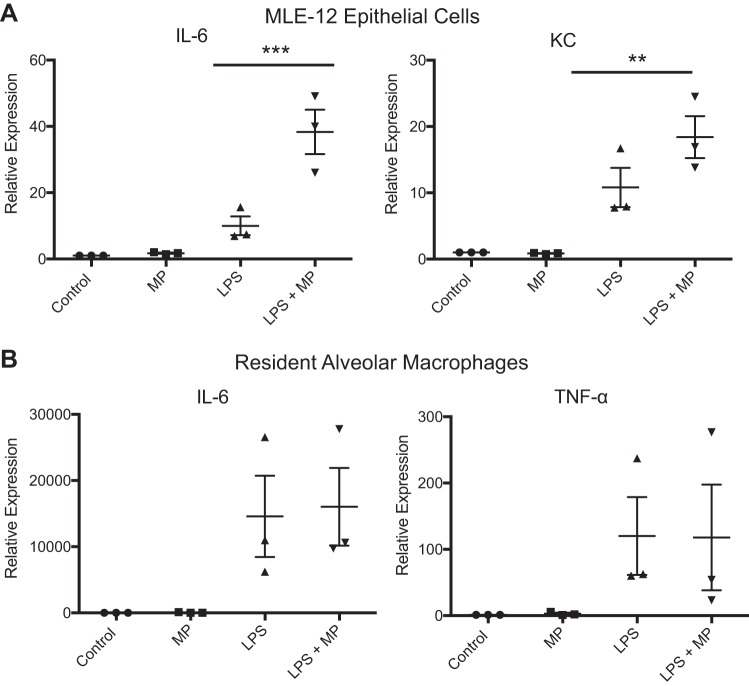

Alveolar microparticles enhance inflammatory signaling in alveolar epithelial cells in vitro but not in alveolar macrophages.

Because prior reports had demonstrated that microparticles can promote inflammation in the setting of acute lung injury, we sought to determine whether this was operative in our systems. Because alveolar particles are likely to contact both AMs and epithelial cells, we exposed both cell types to microparticles. Importantly, since microparticles are largely present during inflammation and in this context have been suggested to amplify inflammatory responses, we also studied their effect on cells primed with LPS. To mimic alveolar epithelial cells, MLE-12 cells were used. AMs were isolated from naïve C57/bl6 mice. In the MLE-12 cells, microparticles did not significantly increase cytokine expression; however, the addition of microparticles to LPS-treated cells synergistically increased the expression of IL-6 and KC (Fig. 8A). This demonstrates that epithelial cells primed toward inflammation, as in the setting of lung injury, respond to microparticles by further increasing proinflammatory signaling. Interestingly, alveolar macrophages showed no response to microparticles alone or with the addition of LPS (Fig. 8B). Taken as a whole, these data support the prevailing concept that microparticles amplify inflammatory responses in the lungs. Our data suggest that this effect may be driven by microparticle-epithelial interaction and that removal of microparticles by resident alveolar macrophages may be one means by which inflammation is dampened.

Fig. 8.

Microparticles are pro-inflammatory toward alveolar epithelial cells in vitro but not alveolar macrophages. A: MLE-12 cells were treated with microparticles (MP), LPS, or LPS and microparticles. RNA was isolated at 4 h, and RT-PCR was performed to quantify the proinflammatory cytokines KC and IL-6. B: resident alveolar macrophages obtained from C57/bl6 mice were treated with microparticles, LPS, or LPS and microparticles. RNA was isolated at 4 h, and RT-PCR was performed to quantify IL-6 and TNFα. Data represent means ± SE; n = 3. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Microparticles are a subset of extracellular vesicles that are defined based on size (0.1–1 μm in diameter) and their distinctive lipid membrane with exposed phosphatidylserine (11). Other cell-derived particles include exosomes (<100 nm) and apoptotic bodies (mostly >1 μm). In this study, we identified microparticles in the alveolar space in two different forms of experimental lung injury and determined their size using flow cytometry and electron microscopy. The presence of PS species, one of the defining characteristics of microparticles, was confirmed by flow cytometry and mass spectrometry. Prior studies have investigated the release of microparticles at single or early time points during the course of acute lung injury (3, 29, 39). In comparison, we chose to quantify their numbers throughout the entire course of lung injury to better explore their removal in the context of resolution of the inflammatory response. Our data show that microparticles accumulate in the alveolar space, following a similar time course as neutrophils in both models of injury. Importantly, neutrophils and microparticles were cleared from injured lungs as macrophages accumulated, consistent with the well-accepted role of macrophages as the primary lung phagocyte.

Microparticles are heterogeneous and vary in terms of size, function, and cell of origin. Accordingly, close attention must be paid to the techniques used to isolate them. In this context, our isolation technique used sequential centrifugation steps to carefully separate BAL fluid constituents based on their density and size. As a first step, a low centrifugal force (200 g) was used to separate cells and apoptotic bodies. This unintentionally eliminated some microparticles, but removed larger constituents. A second, higher-force (10,000 g for 10 min) centrifugation step yielded microparticles with characteristic size and composition. Notably, this strategy would not be expected to isolate exosomes, since they typically require significantly higher forces (∼100,000 g) for longer times (30–60 min) (44). This is important, because given the size and composition difference of microparticles and exosomes, we would anticipate that they could be engulfed by different mechanisms. Importantly, macrophages, as one of the major phagocytes in the body, have been shown to engulf both microparticles (24) as well as exosomes (2). Therefore, determining whether and how alveolar macrophages ingest microparticles during lung inflammation was an important focus in determining how microparticles are cleared during inflammation.

During lung injury, two sets of macrophages exist in the alveolus: resident macrophages and recruited macrophages. As a next step, we sought to determine which alveolar macrophage subsets may endocytose microparticles during acute lung injury. Because we have shown previously that recruited macrophages ingest PS-exposing apoptotic cells more avidly than resident alveolar macrophages (15), we hypothesized that they, too, would be the primary macrophage-ingesting microparticles (which like apoptotic cells contain phosphatidylserine on their cell surface). To our surprise, the resident alveolar macrophages were the dominant subtype that engulfed microparticles during acute lung injury. This finding points to potential specificity of microparticle uptake and suggests a division of labor between the two macrophage cell types. Given the small size of microparticles, we initially hypothesized that macropinocytosis might be an important uptake mechanism. However, amiloride, an inhibitor of macropinocytosis, did not prevent their endocytosis. We also did not see colocalization of fluid phase dextran and the microparticles when they were cultured together, again pointing away from macropinocytosis. Instead, wortmannin and cytochalasin D showed the greatest inhibitory effects. This distinction is important, since the way a cell engulfs particles can impact downstream signaling events (7, 35). The uptake mechanism can also change how the particle is processed once internalized (42). In the case of microparticles, which often contain cargo such as miRNA and cytokines, this processing and trafficking could be of particular importance and could influence how that cargo affects the endocytosing cell. We found that approximately half of the microparticles were internalized into lysosomes by macrophages at 2 h based on pHRodo staining. Although we did not evaluate later time points to assess whether all particles are trafficked to lysosomes, this is an important future area of study.

The finding that microparticles were phagocytosed led us to explore some of the surface molecules associated with phagocytosis and, more specifically, those associated with the binding of PS. The TAM receptors (MerTK, Axl, and Tyro3) have well-documented roles in the uptake of apoptotic cells. Notably, alveolar macrophages express both MerTK and Axl, and both have been shown to be important in the efferocytosis of apoptotic cells in the alveolus during lung injury (9, 19). Although apoptotic cells are much larger than microparticles, the TAM receptors have been implicated in the uptake of very small PS-expressing vesicles, including viruses (27). There is limited data, however, on the role of TAM receptors in the uptake of microparticles (12). We found differential expression of both MerTK and Axl in resident alveolar macrophages relative to recruited macrophages. Using MerTK-deficient mice, we showed that MerTK is required for optimal microparticle uptake. Interestingly, the reduction of uptake in vivo was even greater than that seen ex vivo. There are a number of possible explanations for this finding. Macrophages, like many cells, often experience a change in cellular programming when they are placed in culture, which may decrease their phagocytic capacity. Alternatively, the in vivo environment may have increased levels of bridging molecules Gas6 and Protein S or opsonizing factors such as surfactant proteins A and D. How surfactant proteins interact with microparticles has not yet been explored. Finally, this finding may be due to an effect of isoflurane, which was used as an anesthetic in our in vivo system. Recently, isoflurane has been shown to increase surface expression of MerTK on macrophages (6), which would increase uptake of the microparticles. Whereas MerTK was clearly required for microparticle uptake, Axl inhibition had minimal effect on WT macrophages or MerTK-deficient macrophages, suggesting little role for this TAM receptor.

TAM receptors require bridging molecules such as protein S and Gas6, which bind to PS, to ingest apoptotic cells. We were able to identify that both were present in microparticle pellets, making them available as ligands for the TAM receptors. It is important to recognize that multiple receptors have been shown to recognize PS and play a role in efferocytosis (34). Our RNA-seq data showed that MerTK and Axl were the relevant receptors with the highest expression on resident alveolar macrophages. Given the dominant role for MerTK in our study, we have not yet assessed other potential receptors (i.e., CD36, stabilin 1, and integrin subunit 5). However, in the setting of apoptotic cell uptake, it is known that a variety of receptors can cooperate either by binding or aiding in internalization. At this time we are unable to distinguish whether MerTK is required for the binding or internalization of microparticles, r both. Thus, we have not ruled out that other receptors may aid in the endocytosis of microparticles. Furthermore, we have not yet assessed whether parenchymal lung cells such as alveolar epithelial cells may contribute to the clearance of microparticles as well.

Microparticles are an increasingly recognized mechanism of cell-to-cell signaling, acting as a vehicle to transport cytokines, miRNAs, and mRNAs to target cells. Their role in acute inflammatory lung injury and ARDS pathogenesis is an area of ongoing research, and there are conflicting data regarding their roles during lung injury. It has been suggested that microparticles promote lung injury by driving cytokine release and activating neutrophils (4), increasing alveolar permeability by directly affecting epithelial and endothelial cells (21, 39), and promoting the hypercoagulable state that is seen in ARDS (3, 26). Contrasting work has suggested that microparticles may have a beneficial effect on ARDS resolution (10). We show that microparticles isolated from the alveolus early in inflammation augmented epithelial cell proinflammatory signaling; however, we have not yet explored the mechanism by which the microparticles signal to epithelial cells. Importantly, the microparticles did not promote inflammation in alveolar macrophages. Our work and prior reports speak to the heterogeneity of microparticles, particularly in terms of their cell of origin, and also suggest that microparticles may exert compartment-specific effects (vasculature vs. alveolus). Although we did not definitively explore the cell of origin of the microparticles we isolated, we would hypothesize that, based on prior work, they are released from a variety of cells, including epithelial cells, neutrophils, and macrophages. Future evaluation into individual microparticle populations may provide important information regarding their pro- or anti-inflammatory effects. It is also possible that microparticles isolated at early stages of inflammation are more proinflammatory, whereas particles isolated during resolution have an anti-inflammatory effect. This would be consistent with our findings, as we used microparticles isolated early in inflammation in our in vitro studies.

Herein we demonstrate for the first time the kinetics of microparticle accumulation and clearance in the alveolar space during the full course of experimental acute lung injury. These cell-derived, phosphatidylserine exposing microparticles increase in number, peaking at the time of maximum inflammation, and then decrease during the resolution response. Our findings are consistent with the paradigm of microparticles acting as signaling vehicles, as we show that microparticles isolated early in the setting of inflammation augment inflammatory signaling by alveolar epithelial cells. Microparticles are taken up predominately by resident alveolar macrophages during injury, and our studies show that this is in large part driven by MerTK. In this context, efficient removal of microparticles by AMs may prevent them from eliciting their pro-inflammatory effect on alveolar epithelial cells. These novel findings add to our overall knowledge of the pathophysiology of acute lung injury, and highlight future areas of study that may be beneficial in our search for therapies to treat this common and deadly disease process.

GRANTS

Cancer Center Flow Cytometry Shared Resource at the University of Colorado-Anschutz Medical Campus is supported by Grant P30-CA-046934. This work was also supported by NIH Grants F32-HL-126333 (to M. P. Mohning), F32-HL-131397 (to K. J. Mould), T32-HL-007085 (to A. L. McCubbrey), R01-HL-109517 (to W. J. Janssen), and R01-HL-114381 (to P. M. Henseon).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.P.M., D.B., P.M.H., and W.J.J. conceived and designed research; M.P.M., S.M.T., L.B., K.J.M., and S.C.F. performed experiments; M.P.M., S.M.T., L.B., K.J.M., A.L.M., S.C.F., and W.J.J. analyzed data; M.P.M., S.M.T., K.J.M., A.L.M., S.C.F., D.B., P.M.H., and W.J.J. interpreted results of experiments; M.P.M., S.M.T., S.C.F., and W.J.J. prepared figures; M.P.M. drafted manuscript; M.P.M., S.M.T., L.B., K.J.M., A.L.M., S.C.F., D.B., P.M.H., and W.J.J. edited and revised manuscript; M.P.M., S.M.T., L.B., K.J.M., A.L.M., S.C.F., D.B., P.M.H., and W.J.J. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jan Henson (National Jewish Health) for help and expertise in electron microscopy. M. P. Mohning and K. J. Mould acknowledge the generous support of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Loan Repayment Program through the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aggarwal NR, King LS, D’Alessio FR. Diverse macrophage populations mediate acute lung inflammation and resolution. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 306: L709–L725, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00341.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrès C, Blanc L, Bette-Bobillo P, André S, Mamoun R, Gabius HJ, Vidal M. Galectin-5 is bound onto the surface of rat reticulocyte exosomes and modulates vesicle uptake by macrophages. Blood 115: 696–705, 2010. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-231449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bastarache JA, Fremont RD, Kropski JA, Bossert FR, Ware LB. Procoagulant alveolar microparticles in the lungs of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 297: L1035–L1041, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00214.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buesing KL, Densmore JC, Kaul S, Pritchard KA Jr, Jarzembowski JA, Gourlay DM, Oldham KT. Endothelial microparticles induce inflammation in acute lung injury. J Surg Res 166: 32–39, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Densmore JC, Signorino PR, Ou J, Hatoum OA, Rowe JJ, Shi Y, Kaul S, Jones DW, Sabina RE, Pritchard KA Jr, Guice KS, Oldham KT. Endothelium-derived microparticles induce endothelial dysfunction and acute lung injury. Shock 26: 464–471, 2006. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000228791.10550.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du X, Jiang C, Lv Y, Dull RO, Zhao YY, Schwartz DE, Hu G. Isoflurane promotes phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils through AMPK-mediated ADAM17/Mer signaling. PLoS One 12: e0180213, 2017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Konowal A, Freed PW, Westcott JY, Henson PM. Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells in vitro inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production through autocrine/paracrine mechanisms involving TGF-beta, PGE2, and PAF. J Clin Invest 101: 890–898, 1998. doi: 10.1172/JCI1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frasch SC, McNamee EN, Kominsky D, Jedlicka P, Jakubzick C, Zemski Berry K, Mack M, Furuta GT, Lee JJ, Henson PM, Colgan SP, Bratton DL. G2A Signaling Dampens Colitic Inflammation via Production of IFN-γ. J Immunol 197: 1425–1434, 2016. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujimori T, Grabiec AM, Kaur M, Bell TJ, Fujino N, Cook PC, Svedberg FR, MacDonald AS, Maciewicz RA, Singh D, Hussell T. The Axl receptor tyrosine kinase is a discriminator of macrophage function in the inflamed lung. Mucosal Immunol 8: 1021–1030, 2015. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guervilly C, Lacroix R, Forel JM, Roch A, Camoin-Jau L, Papazian L, Dignat-George F. High levels of circulating leukocyte microparticles are associated with better outcome in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care 15: R31, 2011. doi: 10.1186/cc9978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.György B, Szabó TG, Pásztói M, Pál Z, Misják P, Aradi B, László V, Pállinger E, Pap E, Kittel A, Nagy G, Falus A, Buzás EI. Membrane vesicles, current state-of-the-art: emerging role of extracellular vesicles. Cell Mol Life Sci 68: 2667–2688, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0689-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Happonen KE, Tran S, Mörgelin M, Prince R, Calzavarini S, Angelillo-Scherrer A, Dahlbäck B. The Gas6-Axl protein interaction mediates endothelial uptake of platelet microparticles. J Biol Chem 291: 10586–10601, 2016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.699058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffmann PR, deCathelineau AM, Ogden CA, Leverrier Y, Bratton DL, Daleke DL, Ridley AJ, Fadok VA, Henson PM. Phosphatidylserine (PS) induces PS receptor-mediated macropinocytosis and promotes clearance of apoptotic cells. J Cell Biol 155: 649–659, 2001. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janssen WJ, Barthel L, Muldrow A, Oberley-Deegan RE, Kearns MT, Jakubzick C, Henson PM. Fas determines differential fates of resident and recruited macrophages during resolution of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 184: 547–560, 2011. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1891OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janssen WJ, McPhillips KA, Dickinson MG, Linderman DJ, Morimoto K, Xiao YQ, Oldham KM, Vandivier RW, Henson PM, Gardai SJ. Surfactant proteins A and D suppress alveolar macrophage phagocytosis via interaction with SIRP α. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 178: 158–167, 2008. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200711-1661OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janssen WJ, Muldrow A, Kearns MT, Barthel L, Henson PM. Development and characterization of a lung-protective method of bone marrow transplantation in the mouse. J Immunol Methods 357: 1–9, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerr MC, Teasdale RD. Defining macropinocytosis. Traffic 10: 364–371, 2009. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee YJ, Han JY, Byun J, Park HJ, Park EM, Chong YH, Cho MS, Kang JL. Inhibiting Mer receptor tyrosine kinase suppresses STAT1, SOCS1/3, and NF-κB activation and enhances inflammatory responses in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. J Leukoc Biol 91: 921–932, 2012. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0611289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee YJ, Lee SH, Youn YS, Choi JY, Song KS, Cho MS, Kang JL. Preventing cleavage of Mer promotes efferocytosis and suppresses acute lung injury in bleomycin treated mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 263: 61–72, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lemke G, Rothlin CV. Immunobiology of the TAM receptors. Nat Rev Immunol 8: 327–336, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nri2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Letsiou E, Sammani S, Zhang W, Zhou T, Quijada H, Moreno-Vinasco L, Dudek SM, Garcia JGN. Pathologic mechanical stress and endotoxin exposure increases lung endothelial microparticle shedding. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 52: 193–204, 2015. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0347OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang J, Jung Y, Tighe RM, Xie T, Liu N, Leonard M, Gunn MD, Jiang D, Noble PW. A macrophage subpopulation recruited by CC chemokine ligand-2 clears apoptotic cells in noninfectious lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 302: L933–L940, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00256.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim JP, Gleeson PA. Macropinocytosis: an endocytic pathway for internalising large gulps. Immunol Cell Biol 89: 836–843, 2011. doi: 10.1038/icb.2011.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Litvack ML, Post M, Palaniyar N. IgM promotes the clearance of small particles and apoptotic microparticles by macrophages. PLoS One 6: e17223, 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Majoor CJ, van de Pol MA, Kamphuisen PW, Meijers JC, Molenkamp R, Wolthers KC, van der Poll T, Nieuwland R, Johnston SL, Sterk PJ, Bel EH, Lutter R, van der Sluijs KF. Evaluation of coagulation activation after rhinovirus infection in patients with asthma and healthy control subjects: an observational study. Respir Res 15: 14, 2014. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-15-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McVey M, Tabuchi A, Kuebler WM. Microparticles and acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 303: L364–L381, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00354.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moller-Tank S, Maury W. Phosphatidylserine receptors: enhancers of enveloped virus entry and infection. Virology 468-470: 565–580, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mould KJ, Barthel L, Mohning MP, Thomas SM, McCubbrey AL, Danhorn T, Leach SM, Fingerlin TE, O’Connor BP, Reisz JA, D’Alessandro A, Bratton DL, Jakubzick CV, Janssen WJ. Cell origin dictates programming of resident versus recruited macrophages during acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 57: 294–306, 2017. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2017-0061OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mutschler DK, Larsson AO, Basu S, Nordgren A, Eriksson MB. Effects of mechanical ventilation on platelet microparticles in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Thromb Res 108: 215–220, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(03)00005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nandrot EF, Anand M, Almeida D, Atabai K, Sheppard D, Finnemann SC. Essential role for MFG-E8 as ligand for αvβ5 integrin in diurnal retinal phagocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 12005–12010, 2007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704756104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nieri D, Neri T, Petrini S, Vagaggini B, Paggiaro P, Celi A. Cell-derived microparticles and the lung. Eur Respir Rev 25: 266–277, 2016. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0009-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Novelli F, Neri T, Tavanti L, Armani C, Noce C, Falaschi F, Bartoli ML, Martino F, Palla A, Celi A, Paggiaro P. Procoagulant, tissue factor-bearing microparticles in bronchoalveolar lavage of interstitial lung disease patients: an observational study. PLoS One 9: e95013, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel BV, Tatham KC, Wilson MR, O’Dea KP, Takata M. In vivo compartmental analysis of leukocytes in mouse lungs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 309: L639–L652, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00140.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Penberthy KK, Ravichandran KS. Apoptotic cell recognition receptors and scavenger receptors. Immunol Rev 269: 44–59, 2016. doi: 10.1111/imr.12376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poon IK, Lucas CD, Rossi AG, Ravichandran KS. Apoptotic cell clearance: basic biology and therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Immunol 14: 166–180, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nri3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robb CT, Regan KH, Dorward DA, Rossi AG. Key mechanisms governing resolution of lung inflammation. Semin Immunopathol 38: 425–448, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s00281-016-0560-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rothlin CV, Carrera-Silva EA, Bosurgi L, Ghosh S. TAM receptor signaling in immune homeostasis. Annu Rev Immunol 33: 355–391, 2015. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schaefer BC, Schaefer ML, Kappler JW, Marrack P, Kedl RM. Observation of antigen-dependent CD8+ T-cell/dendritic cell interactions in vivo. Cell Immunol 214: 110–122, 2001. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2001.1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soni S, Wilson MR, O’Dea KP, Yoshida M, Katbeh U, Woods SJ, Takata M. Alveolar macrophage-derived microvesicles mediate acute lung injury. Thorax 71: 1020–1029, 2016. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-208032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Théry C, Ostrowski M, Segura E. Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol 9: 581–593, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nri2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomashow MA, Shimbo D, Parikh MA, Hoffman EA, Vogel-Claussen J, Hueper K, Fu J, Liu CY, Bluemke DA, Ventetuolo CE, Doyle MF, Barr RG. Endothelial microparticles in mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and emphysema. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 188: 60–68, 2013. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201209-1697OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Underhill DM, Goodridge HS. Information processing during phagocytosis. Nat Rev Immunol 12: 492–502, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nri3244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Pol E, Böing AN, Harrison P, Sturk A, Nieuwland R. Classification, functions, and clinical relevance of extracellular vesicles. Pharmacol Rev 64: 676–705, 2012. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.005983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Witwer KW, Buzás EI, Bemis LT, Bora A, Lässer C, Lötvall J, Nolte-’t Hoen EN, Piper MG, Sivaraman S, Skog J, Théry C, Wauben MH, Hochberg F. Standardization of sample collection, isolation and analysis methods in extracellular vesicle research. J Extracell Vesicles 2: 20360, 2013. doi: 10.3402/jev.v2i0.20360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zemans RL, Henson PM, Henson JE, Janssen WJ. Conceptual approaches to lung injury and repair. Ann Am Thorac Soc 12, Suppl 1: S9–S15, 2015. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201408-402MG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]