Abstract

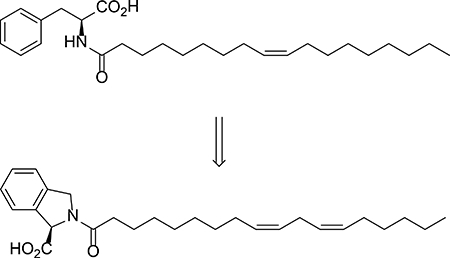

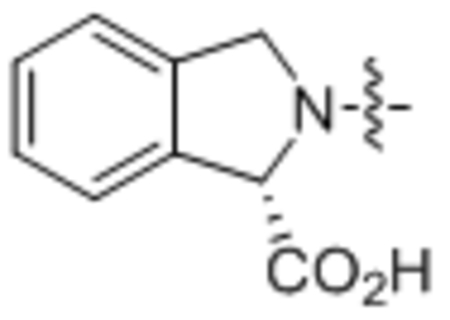

We report the full account of the synthesis and mitochondrial uncoupling bioactivity of N-acyl amino acids and their unnatural analogs. Unsaturated fatty acid chains of medium length and neutral amino acid head groups are required for optimal uncoupling activity on mammalian cells. A class of unnatural N-acyl amino acid analogs, characterized by isoindoline-1-carboxylate head groups (37), were resistant to enzymatic degradation by PM20D1 and maintained uncoupling bioactivity in cells and in mice.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The N-acyl amino acids are a class of endogenous lipid metabolites with pleotropic bioactivities1. Specific members of this metabolite class include N-oleoyl serine, N-arachidonoyl glycine, and N-oleoyl glycine, which have been shown to regulate bone remodeling2, pain sensation3, and food intake4, respectively. At a molecular level, these lipids can act as ligands for ion channels5 (e.g., TRPV1) or G-protein coupled receptors6 (e.g., GPR92). To date, over fifty distinct species of N-acyl amino acids have been detected in mammalian tissues7. However, the full spectrum of the biological functions for this class of endogenous lipids remain incompletely characterized.

We have recently identified a novel function for several N-acyl amino acids, including N-oleoyl leucine, N-oleoyl phenylalanine, and N-arachidonoyl glycine. These compounds can act as lipid uncouplers of mitochondrial respiration, stimulating respiration on isolated mitochondria, in cells, and in mice8. Key to this discovery was the annotation of the circulating factor peptidase M20 domain containing 1 (PM20D1) as a dominant enzyme that regulates N-acyl amino acid levels in vivo. Genetically increased circulating PM20D1 by adeno-associated virus (AAV) delivery to liver augments circulating N-acyl amino acids, leading to increased respiration and blunted weight gain on high fat diet in mice. Direct administration of N-acyl amino acids to mice by intraperitoneal (IP) injection also produces increased whole body energy expenditure with weight loss and improved glucose homeostasis. Mechanistically, N-acyl amino acids directly act on isolated mitochondria to increase respiration, potentially by interacting with the SLC25 family of inner mitochondrial transporters9.

To more fully understand how N-acyl amino acids stimulate respiration, we herein disclose a full account of the structure-activity relationships of N-acyl amino acids and their uncoupling bioactivity. The uncoupling activity of this metabolite class is largely restricted to those with neutral amino acid head groups and desaturated fatty acyl chains of medium length. By exploring unnatural analogs of these metabolites, we identified the proline derivative N-oleoyl-isoindoline-1-carboxylate 37 as a semisynthetic N acyl amino acid analog with exceptional uncoupling activity. 37 possessed uncoupling activity in cells and in mice, but unlike the natural metabolites, was entirely resistant to enzymatic hydrolysis by PM20D1.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

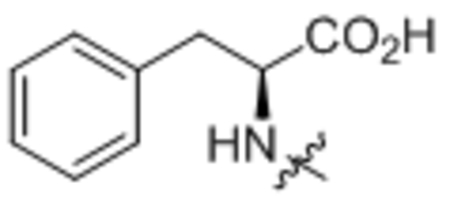

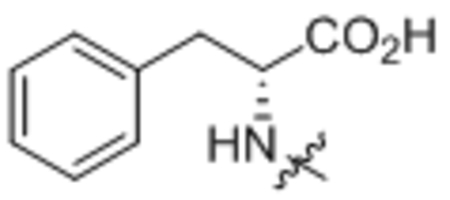

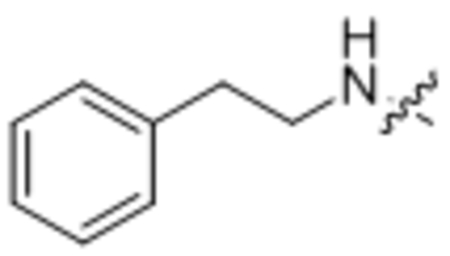

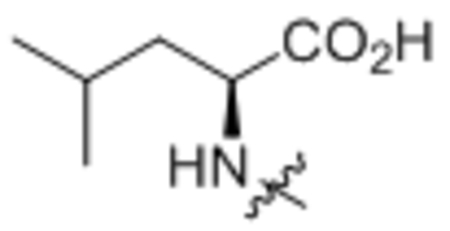

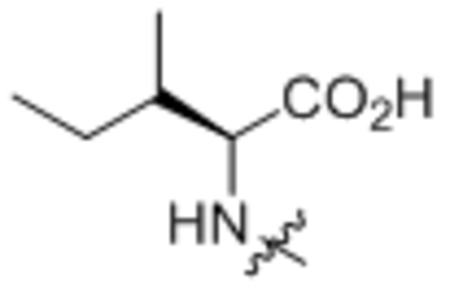

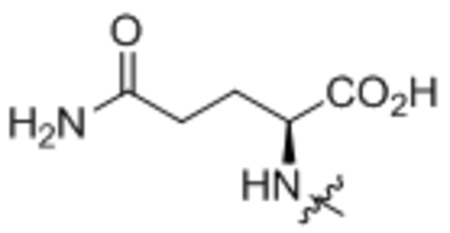

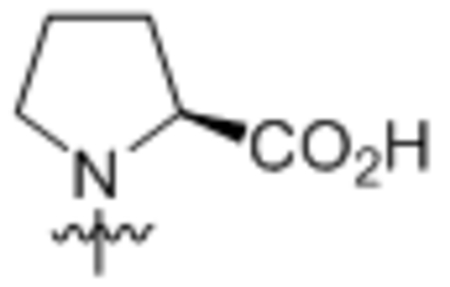

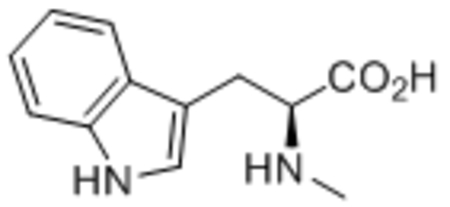

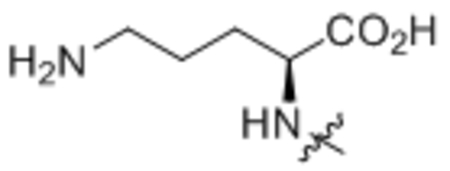

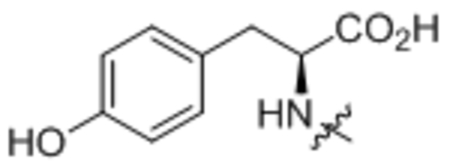

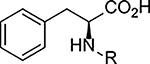

To determine the uncoupling activity of the N acyl amino acid analogs, we tested their effect on cellular respiration of C2C12 mouse myoblast cells. Because these compounds show a time-dependent effect on changes in respiration, for standardization of our assay results we report the maximal stimulation of respiration as compared to DMSO-control. Further standardizing our respiration assays, all compounds were assayed at 50 μM. First, we fixed the fatty acid chain to oleic acid. As previously reported, C18:1-Phe possess potent uncoupling bioactivity8, stimulating respiration to ~160% of baseline levels (Table 1, compound 1). Amino acid stereoselectivity was not observed in this uncoupling bioactivity as both C18:1-D-Phe and C18:1-L-Phe equivalently stimulated cellular respiration (Table 1, compound 2). Consistent with our previous report, the amino acid head group carboxylate was absolutely required for activity: removal of the carboxylate moiety entirely abolished uncoupling activity (Table 1, compound 3). Next, by varying the amino acid head group, we found that whereas amino acids containing neutral side chains (e.g., Leu, Ile, Gln, Pro, Trp, compounds 4 – 8) were potent uncouplers, those compounds with charged side chains (e.g., Lys, Tyr, Glu, compounds 9 – 11) were unable to induce respiration (Table 1). Some tolerance for backbone steric modifications were acceptable on the amino acid side. For instance, inclusion of homoglycine or dipeptide Gly-Gly head group preserved uncoupling bioactivity (Table 1, compounds 12 and 13).

Table 1. Structure and uncoupling bioactivity of compounds with different amino acid head groups.

Respiration in C2C12 cells is shown as maximal increases versus basal oligomycin-treated respiration, which is normalized to 100%. Data are shown as means ± SEM, n=3–6/group.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Head group name | R = | % stimulation of respiration (baseline = 100%) |

| 1 | L-Phe |  |

161 ± 12 |

| 2 | D-Phe |  |

173 ± 9 |

| 3 | n/a |  |

104 ± 4 |

| 4 | L-Leu |  |

178 ± 13 |

| 5 | L-Ile |  |

167 ± 14 |

| 6 | L-Gln |  |

164 ± 4 |

| 7 | L-Pro |  |

182 ± 7 |

| 8 | L-Trp |  |

147 ± 9 |

| 9 | L-Lys |  |

108 ± 4 |

| 10 | L-Tyr |  |

105 ± 13 |

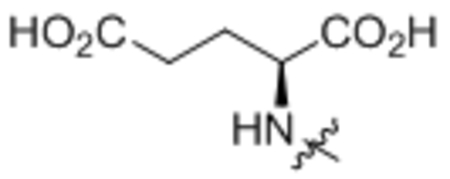

| 11 | L-Glu |  |

106 ± 7 |

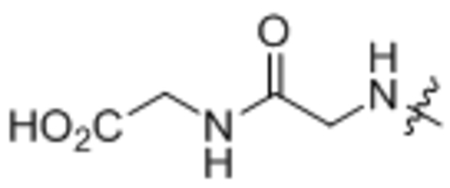

| 12 | Gly-Gly |  |

206 ± 32 |

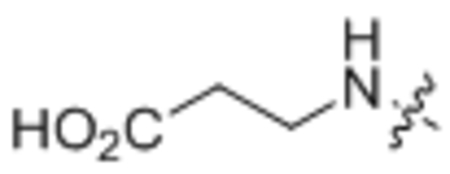

| 13 | Homoglycine |  |

185 ± 10 |

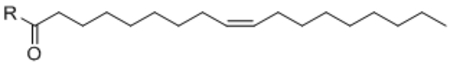

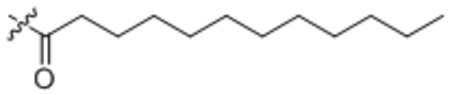

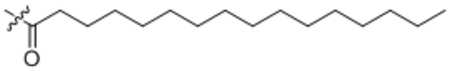

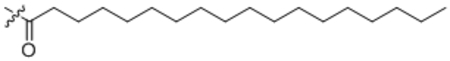

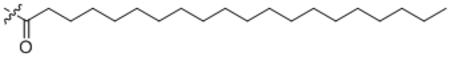

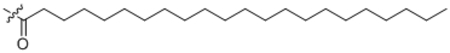

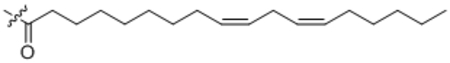

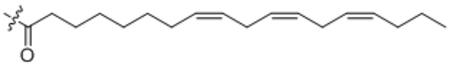

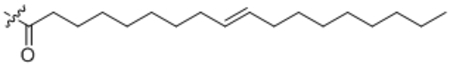

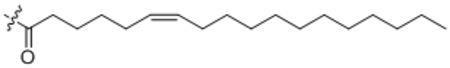

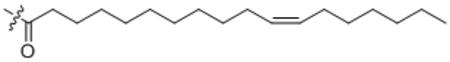

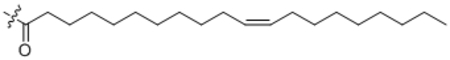

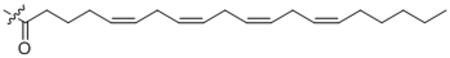

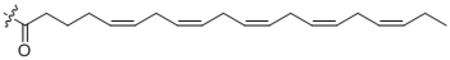

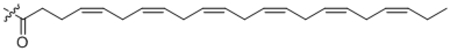

For the fatty acid side chain, we observed striking structural requirements regarding length and type of desaturation for uncoupling bioactivity. By sequentially stepping through increasing fatty acid chain lengths, we found that fatty acyl chains that were too short (e.g., < C12:0) or too long (e.g., >C20:0) did not possess uncoupling activity (Table 2, compounds 14 – 18). Within the “medium” fatty acyl chain range, specific types of desaturation potently improve the respiration response. For instance, we observed a step-wise increase in uncoupling activity from C18:0-Phe < C18:1-Phe < C18:2-Phe (compound 16 vs. 1 vs. 19) that, surprisingly, precipitously drops off with C18:3-Phe (compound 20). Other specific olefin perturbations also underscored the importance of specific types and locations of desaturation. For instance, compared to cis-Δ9-C18:1-Phe (compound 1), trans-Δ9-C18:1-Phe (Table 2, compound 21) olefin shows essentially no uncoupling bioactivity. Similarly, cis-Δ6-C18:1-Phe and cis-Δ11-C18:1-Phe (Table 3, compound 22 and 23) were all inferior to the parent compound 1.

Table 2. Structure and uncoupling bioactivity of compounds with different fatty acid side chains.

Respiration in C2C12 cells is shown as maximal increases versus basal oligomycin-treated respiration, which is normalized to 100%. Data are shown as means ± SEM, n=3–6/group.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd | Fatty acid name | R = | % stimulation of respiration (baseline = 100%) |

| 14 | C12:0 |  |

96 ± 4 |

| 15 | C16:0 |  |

180 ± 20 |

| 16 | C18:0 |  |

148 ± 12 |

| 17 | C20:0 |  |

95 ± 8 |

| 18 | C22:0 |  |

100 ± 3 |

| 19 | C18:2 |  |

218 ± 10 |

| 20 | C18:3 |  |

109 ± 12 |

| 21 | trans-C18:1 |  |

107 ± 3 |

| 22 | Δ6-C18:1 |  |

110 ± 12 |

| 23 | Δ11-C18:1 |  |

115 ± 8 |

| 24 | C20:1 |  |

103 ± 3 |

| 25 | C20:4 |  |

200 ± 12 |

| 26 | C20:5 |  |

259 ± 43 |

| 27 | C22:6 |  |

166 ± 11 |

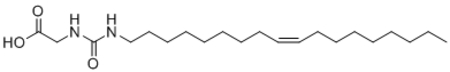

Table 3. Structure and uncoupling bioactivity of unnatural urea-containing N-acyl amino acid analogs.

Respiration in C2C12 cells is shown as maximal increases versus basal oligomycin-treated respiration, which is normalized to 100%. Data are shown as means ± SEM, n=3–6/group.

| Compound | Structure | % stimulation of respiration (baseline = 100%) |

|---|---|---|

| 28 |  |

104 ± 3 |

| 29 |  |

97 ± 5 |

Given the strong influences of desaturation on the acyl chain length, we systematically introduced increasing desaturation to C20:0-Phe (compound 17), a parent compound that initially does not possess any uncoupling activity. Again, increasing desaturation augments uncoupling bioactivity with an apparent optimal desaturation at C20:4 (Table 2, compounds 24 – 26). A similar strategy to increase desaturation also converted an uncoupling-incompetent C22:0-Phe (compound 18) into a potent uncoupler (C22:6-Phe, compound 27). These specific requirements for desaturation is reminiscent to that observed for cannabinoid receptor ligands, where only arachidonoyl- but not other fatty acyl-containing lipids can efficient act as agonists for the receptor10. The striking desaturation specificity observed in this N-acyl amino acid series (Table 2) is consistent with interactions with proteinaceous factors that mediate uncoupling. Taken together, our data map out the optimal requirements for uncoupling responses within the N-acyl amino acid class: an uncharged carboxylate-containing head group, a medium fatty acid chain length, and specific sites of desaturation along the acyl chain.

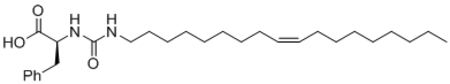

Given the striking structure activity relationships we observed by simply varying the two sides of the amide bond, we next explored unnatural N-acyl amino acid analogs to identify those that may possess superior properties as compared to the naturally occurring metabolites, with the ultimate goal of developing improved uncoupler analogs that might be useful for the treatment of obesity and metabolic disease11–12. Towards this end, we synthesized two urea analogs of C18:1-Gly and C18:1-Phe that we hypothesized might be less metabolically labile compared to the natural amides and tested their effects on cellular respiration. Disappointingly, both urea analogs failed to induce respiration on cells, demonstrating a strict requirement for the presence of an amide bond in the bioactivity of this class of compounds (Table 3).

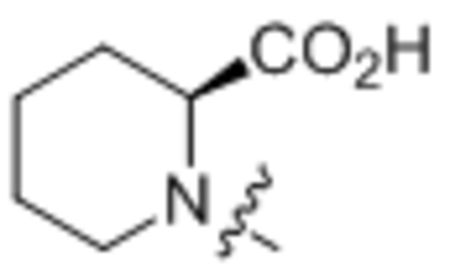

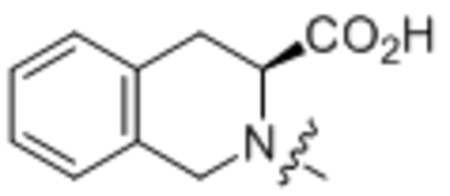

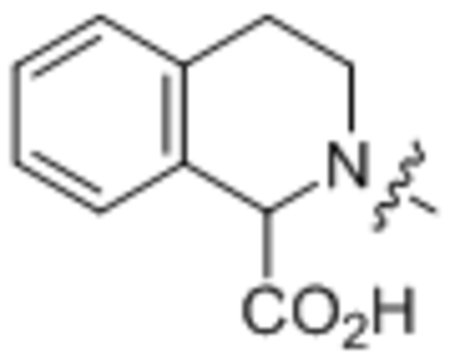

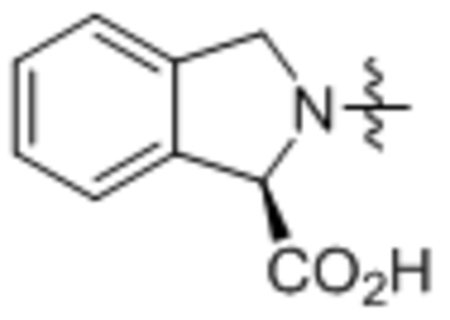

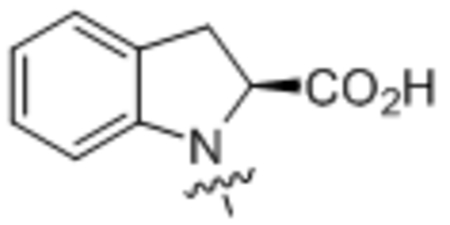

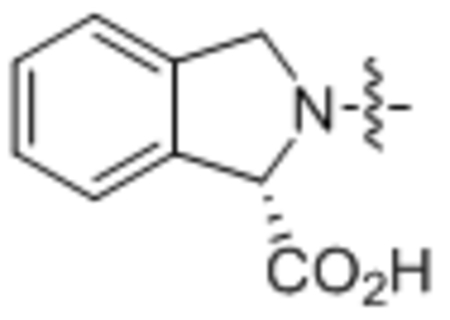

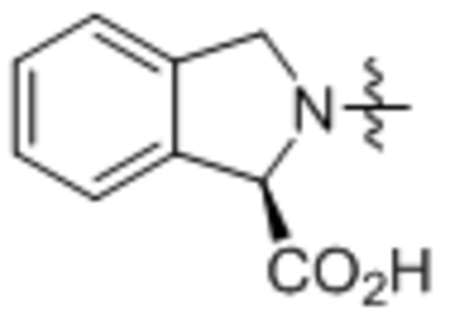

We therefore focused our efforts on potential unnatural modifications to the amino acid head groups. We were intrigued by the potent uncoupling observed with C18:1-Pro (compound 7) and noted that this derivative with a cyclic head group is the most structurally distinct from the other N-acyl amino acids tested. We therefore synthesized and tested in respiration assays a variety of unnatural proline and homoproline N-acyl amino acid derivatives with oleate as a fatty acyl chain so that they could be directly compared to the naturally occurring N-acyl amino acids. Testing of these unnatural analogs in cellular respiration assays revealed that they all stimulated uncoupled respiration to a maximum of ~150–240% over control levels (Table 4, compounds 30 – 35). Derivatization of these isoindoline head groups with linoleoyl instead of oleoyl acyl groups also produced potent unnatural uncouplers (Table 4, compounds 36 and 37). Therefore these analogs 30 – 37 demonstrate that the uncoupling bioactivity of N-acyl amino acids can extend beyond structures containing only the proteinogenic amino acids.

Table 4. Structure and uncoupling bioactivity of compounds with unnatural proline- and homoproline-drived head groups.

Respiration in C2C12 cells is shown as maximal increases versus basal oligomycin-treated respiration, which is normalized to 100%. Data are shown as means ± SEM, n=3–6/group.

| Compound | Fatty acid | R = | % stimulation of respiration (baseline = 100%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | C18:1 |  |

174 ± 3 |

| 31 | C18:1 |  |

187 ± 19 |

| 21 | C18:1 |  |

216 ± 17 |

| 33 | C18:1 |  |

240 ± 24 |

| 34 | C18:1 |  |

190 ± 12 |

| 35 | C18:1 |  |

146 ± 5 |

| 36 | C18:2 |  |

185 ± 18 |

| 37 | C18:2 |  |

190 ± 12 |

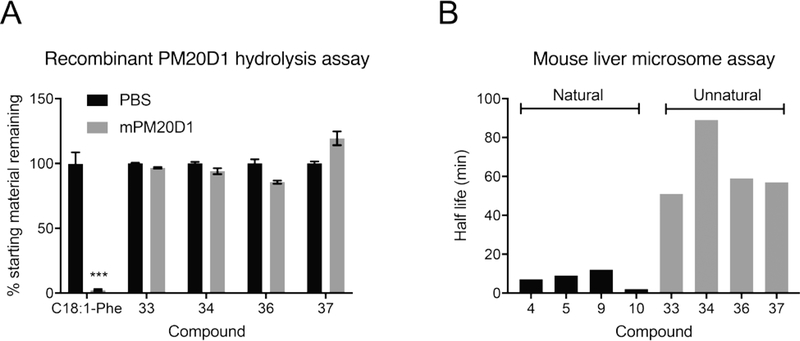

N-acyl amino acids can be hydrolytically inactivated by PM20D1, a bidirectional amidase that in the “hydrolytic” direction can cleave fatty acid amides to liberate free fatty acids and free amino acids8. Given the unusual cyclic structures of 30 – 37, we hypothesized that these analogs might have altered hydrolysis rates. We therefore incubated purified, recombinant murine PM20D1 with a conical N-acyl amino acid substrate, N-arachidonoyl glycine, or one of the unnatural N-acyl amino acids. We observed >90% hydrolysis of N-arachidonoyl glycine to arachidonic acid in our assay conditions, demonstrating that this enzyme efficiently cleaves naturally occurring N-acyl amino acids. Remarkably, all unnatural N-acyl amino acids tested were completely resistant to PM20D1-mediated hydrolysis (Fig. 1a). Consistent with these observations, when endogenously occurring N-acyl amino acids and unnatural analogs were incubated with mouse liver microsomes, the unnatural analogs also maintained exceptionally long half-lives (Fig. 1b): as a group, the average half-life of the natural N-oleoyl amino acids was 8 min, whereas the average for N-oleoyl analogs with unnatural head groups was 64 min. These data therefore demonstrate that changing the amide head group can alter potential downstream metabolism and half-life of N-acyl amino acid analogs.

Fig. 1.

(A) Amount of the indicated compound remaining in the presence of PBS or recombinant, murine PM20D1 after incubation at 37ºC for 1 h. Data are shown as means ± SEM, n = 3/group. *** P < 0.001. (B) Half-life (min) of the indicated compound after incubation in mouse liver microsomes. “Natural” indicates endogenously present N-acyl amino acid whereas “unnatural” indicates an N-acyl amino acid analog with a synthetic head group.

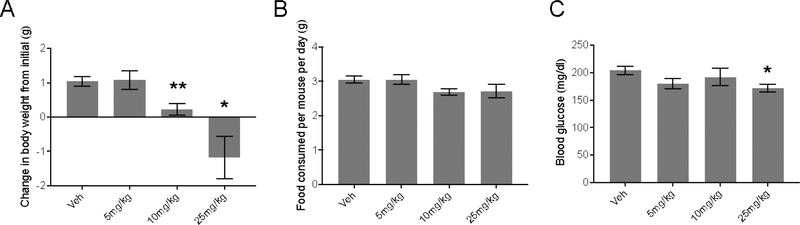

Lastly, we tested the uncoupling bioactivity of unnatural N-acyl amino acid analogs in mice. Towards this end, we adopted a previously used assay in which mice rendered obese by high fat diet feeding (diet-induced obesity, DIO) are given N-acyl amino acids daily by IP administration. Synthetic chemical uncouplers including 2,4-dinitrophenol have been shown to blunt weight gain in this model12 and N-acyl amino acid administration leads to weight loss8. For these experiments, we selected compound 37 because this compound showed excellent uncoupling bioactivity (Table 4) and also resistance to hydrolysis (Fig. 1). DIO mice (initial weight, 46.8 ± 0.6 g) were treated with increasing doses of compound 37 (5, 10, and 25 mg/kg/day IP) daily for 7 consecutive days (Fig. 2a). Though no weight differences were observed at 5 mg/kg vs. vehicle-trteated mice, both 10 and 25 mg/kg doses of compound 37 led to dose-dependent blunting of body weight gain (net weight change, 0.2 ± 0.2 g and –1.2 ± 0.6 g, respectively, vs. 1.1 ± 0.1 g for vehicle-treated mice, P < 0.05 for each comparison). Food intake was slightly but not statistically significantly reduced in mice at these higher doses (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, ad lib blood glucose 2 h after the last compound injection was significantly lower in mice treated with 25 mg/kg compound 37 versus vehicle-treated mice (172 ± 7 mg/dl versus 204 ± 7 mg/dl, respectively, Fig. 2c). These data therefore indicate that unnatural N-acyl amino acids with isoindoline head groups maintain uncoupling bioactivity in vivo.

Fig. 2.

(A-C) Total change in body weight (A), food intake (B), and ad lib blood glucose (C) of diet-induced obese mice (19 weeks high fat diet) after 7 days daily treatment with the indicated dose (IP) of compound 37. Prior to compound administration, mouse weights were not different between the groups (average weight across all groups, 46.8 ± 0.6 g). Data are shown as means ± SEM, n=5/group. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 for the indicated dose versus vehicle-treated mice.

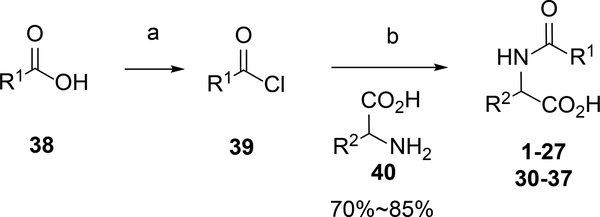

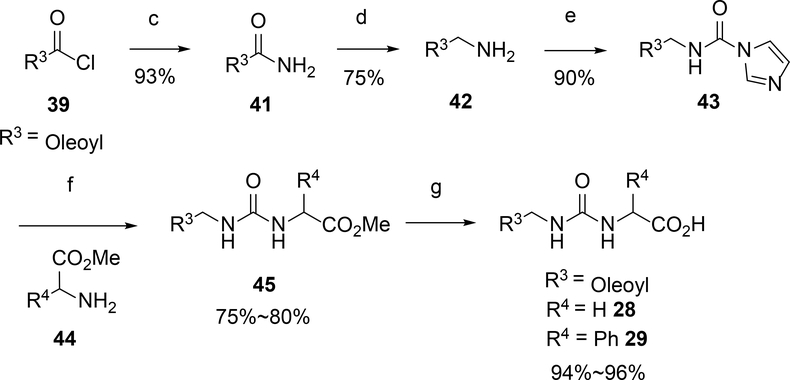

Chemistry

Compounds were synthesized as depicted in Scheme 1 following well-known procedures. Commercial available acyl chloride 39, or converted from acid 38 with oxalyl chloride, coupled with corresponding natural or unnatural amino acid 40 to provide N acyl amino acid analogs 1–27 and 30–37 (Scheme 1). Oleoyl chloride reacted with ammonia hydroxide to give primary amide 41, which was reduced by LiAlH4 to provide primary amine 42. Imidazole intermediate 43 was obtained by coupled amine 42 with CDI, which reacted with amino esters 44 in the presence of DIPEA. The resulted urea esters 45 were hydrolysis by LiOH to provide the desired urea analogs 28 or 29 in good yields (Scheme 2).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Natural and Unnatural N Acyl Amino Acid Analogsa

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Urea Analogsa

a Reaction conditions: (a) oxalyl chloride, DMF, DCM; (b) NaOH, THF/H2O; (c) NH4OH, THF; (d) LiAlH4, THF; (e) CDI, DCM; (f) DIPEA, DCM; (g) LiOH, then HCl.

CONCLUSIONS

Here we provide a detailed account of the synthesis and structure activity relationships of the N-acyl amino acids and their uncoupling activity on mammalian cells. Our data reveal the structural requirements for the uncoupling bioactivity of this class of endogenous metabolites, which include a strict requirement for neutral carboxylate-containing head groups, medium chain fatty acids with specific desaturation, and an amide bond. Through exploration of unnatural N-acyl amino acid analogs, we identify isoindoline 37 as a potent compound as a hydrolysis resistant compound that maintains uncoupling bioactivity in cells and in vivo. Projecting forward, compound 37 or other hydrolysis-resistant N-acyl amino acid analogs may serve as useful probes for understanding the full spectrum of bioactivities associated with the N-acyl amino acid family of lipids. Such compounds may also serve as leads for alternative structural classes of chemical uncouplers that may have enlarged therapeutic windows or altered beneficial and adverse profiles compared with the more “classical” chemical uncouplers such as 2,4-dinitrophenol.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Chemistry.

All solvents and chemicals were reagent grade. Unless otherwise mentioned, all reagents and solvents were purchased from commercial vendors and used as received. Flash column chromatography was carried out on a Teledyne ISCO CombiFlash Rf system using prepacked columns. Solvents used include hexane, ethyl acetate (EtOAc), dichloromethane and methanol. Purity and characterization of compounds were established by a combination of HPLC, TLC, mass spectrometry, and NMR analyses. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance DPX-400 (400 MHz) spectrometer and were determined in chloroform-d or DMSO-d6 with solvent peaks as the internal reference. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm relative to the reference signal, and coupling constant (J) values are reported in hertz (Hz). Thin layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on EMD precoated silica gel 60 F254 plates, and spots were visualized with UV light or iodine staining. Low resolution mass spectra were obtained using a Thermo Scientific ultimate 3000/ LCQ Fleet system (ESI). High resolution mass spectra were obtained using a Thermo Scientific EXACTIVE system (ESI).All test compounds were greater than 95% pure as determined by NMR on a Bruker Avance DPX-400 (400 MHz) spectrometer.

General procedure A.

To a mixture of amino acid (2 eq.) in acetone and water (0.1 M) was added K2CO3 (3 eq.) and acyl chloride (1 eq.) at 0 oC. Then the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight before acidified by HCl (1 M) until pH<3. The mixture was extracted with ethyl estate, washed with brine. The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and filtered. The filtrate was concentrated in vacuo, and the residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, ethyl acetate/hexanes) to give the desired product.

General procedure B.

To a solution of fatty acid (1 eq.) in DCM was added with oxalyl chloride (1.2 eq.) and one drop of DMF at 0 oC. Then the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 hours. The mixture was concentrated and dissolved in DCM, added to a suspension of amino acid (1.5 eq.) and DIPEA (2 eq.) in DCM. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight before acidified by HCl (1.0 M) to pH<3. The result mixture was extracted with DCM, washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. Then the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel to give the product.

General procedure C.

Step 1:To a solution of oleoyl chloride (1 g) in THF (20 mL) was added ammonia hydroxide (10 eq.) at 0 oC. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 hours. Then the mixture was filtered to give the desired oleamide 41 as a white solid (796 mg, 86%).Step 2: To a suspension of LiAlH4 (2 eq.) in THF was added oleamide in one portion at 0 oC. The mixture was heated to reflux overnight. Then the mixture was quenched with water (3 drops) at 0 oC, added with 1 M NaOH solution, stirred at room temperature for 1 hour. The suspension was filtered through celite. The filtrate was diluted with EA, washed with water and brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated to give (Z)-octadec-9-en-1-amine 42 (726 mg, 95%) which was used for the next step without further purification. Step 3: To a solution of (Z)-octadec-9-en-1-amine 42 in DMF was added DIEA (2 eq.) and CDI (1.5 eq.) at 0 oC. Then the mix was stirred at room temperature overnight. The mixture was diluted with ethyl acetate, washed with NaHCO3, brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated, purified on silica gel to give (Z)-N-(octadec-9-en-1-yl)-1H-imidazole-1-carboxamide 43 (795 mg, 81%). Step 4: To a solution of (Z)-N-(octadec-9-en-1-yl)-1H-imidazole-1-carboxamide 43 in DMF was added DIEA (2 eq.) and amino ester 44. Then the mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. Then the mixture was diluted with ethyl acetate, washed with NaHCO3, brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated, purified on silica gel to give intermediate 45 (75–80%). Step 5: To a solution of intermediate 45 in THF and H2O (1:1) was added LiOH (5 eq.). Then the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 hours. The mixture was acidified with HCl (1M) until pH<3. Then the mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate, washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated to give the desired compound 28 or 29 (94–96%).

Oleoyl-L-phenylalanine (1).

Compound 1 was prepared from oleoyl chloride and L-phenyl alanine following the general procedure A as a white solid (1.3 g, 86%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 0.85 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 3H), 1.09–1.31 (m, 22H), 1.33–1.40 (m, 2H), 1.95–2.04 (m, 6H), 2.82 (dd, J = 10.0, 13.8 Hz, 1H), 3.04 (dd, J = 4.7, 13.4 Hz, 1H), 4.38–4.44 (m, 1H), 5.29–5.36 (m, 2H), 7.16–7.28 (m, 5H), 8.08 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 12.61 (brs, 1H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C27H44NO3 [M+H]+ 430.3316, found: 430.3317.

Oleoyl-D-phenylalanine (2).

Compound 2 was prepared from oleoyl chloride and D-phenyl alanine following the general procedure A as a white solid (35 mg, 88%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.89 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H), 1.20–1.43 (m, 22H), 1.53–1.62 (m, 2H), 1.95–2.08 (m, 4H), 2.19 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 3.11–3.28 (m, 2H), 4.86–4.91 (m, 1H), 5.32–5.42 (m, 2H), 5.92 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.16–7.34 (m, 5H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C27H44NO3 [M+H]+ 430.3316, found: 430.3309.

N-phenethyloleamide (3).

Compound 3 was prepared from oleoyl chloride and 2-phenylethan-1-amine following the general procedure A as a white solid (45 mg, 90%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.89 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H), 1.23–1.40 (m, 20H), 1.57–1.62 (m, 2H), 1.99–2.05 (m, 4H), 2.12 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 2.83 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 3.54 (dd, J = 4.7, 13.4 Hz, 2H), 5.34–5.42 (m, 3H), 7.19–7.26 (m, 3H), 7.31–7.34 (m, 2H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C26H46NO [M+H]+ 386.3417, found: 386.3415

Oleoyl-L-leucine (4).

Compound 4 was prepared from oleoyl chloride and L-leucine following the general procedure A as a white solid (2.5 g, 83%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.88 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 0.95 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 3H), 0.97(d, J = 3.6 Hz, 3H), 1.27–1.37 (m, 20H), 1.56–1.77 (m, 5H), 1.98–2.06 (m, 4H), 2.22 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 4.58–4.64 (m, 1H), 5.31–5.39 (m, 2H), 5.86 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C24H46NO3 [M+H]+ 396.3472, found: : 396.3478.

Oleoyl-L-isoleucine (5).

Compound 5 was prepared from oleoyl chloride and L-isoleucine following the general procedure A as a white solid (230 mg, 87%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 0.81–0.88 (m, 6H),1.19–1.32 (m, 22H), 1.34–1.52 (m, 3H), 1.70–1.80 (m, 1H), 1.93–2.03 (m, 4H), 2.06–2.22 (m, 2H), 4.17 (dd, J = 6.2, 8.4 Hz, 1H), 5.28–5.36 (m, 2H), 7.92 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 12.50 (brs, 1H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C24H46NO3 [M+H]+ 396.3472, found: 396.3474.

Oleoyl-L-glutamine (6).

Compound 6 was prepared from oleoyl chloride and L-glutamine following the general procedure A as a white solid (28 mg, 78%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.88 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 1.19–1.38 (m, 20H), 1.58–1.68 (m, 2H), 1.93–2.07 (m, 5H), 2.25 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 2.38–2.48 (m, 1H), 2.54–2.65 (m, 1H), 4.46 (dd, J = 6.2, 12.0 Hz, 1H), 5.30–5.38 (m, 2H), 6.17 (brs, 1H), 6.48 (brs, 1H), 7.18 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C23H43N2O4 [M+H]+ 411.3217, found: 411.3224.

Oleoyl-L-proline (7).

Compound 7 was prepared from oleoyl chloride and L-proline following the general procedure A as a white solid (27 mg, 76%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.89 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 1.19–1.38 (m, 20H), 1.64–1.72 (m, 2H), 1.90–2.10 (m, 6H), 2.37 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 2.50–2.56 (m, 1H), 3.43–3.48 (m, 1H), 3.56–3.60 (m, 1H), 4.63 (dd, J = 6.2, 12.0 Hz, 1H), 5.30–5.38 (m, 2H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C23H42NO3 [M+H]+ 380.3159, found: 380.3143.

Oleoyl-L-tryptophan (8).

Compound 8 was prepared from oleoyl chloride and L-tryptophan following the general procedure A as a white solid (20 mg, 73%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.88 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 1.19–1.38 (m, 22H), 1.47–1.58 (m, 2H), 1.94–2.06 (m, 4H), 2.07–2.17 (m, 2H), 3.30–3.42 (m, 2H), 4.91–4.96 (m, 1H), 5.29–5.38 (m, 2H), 6.00 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H), 7.12 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.21 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 8.22 (brs, 1H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C29H45N2O3 [M+H]+ 469.3425, found: 469.3433.

Oleoyl-L-lysine (9).

Compound 9 was prepared from oleoyl chloride and mono Boc protected L-lysine following the general procedure A, then de-boc with TFA as a white solid (15 mg, 71%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.84 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 1.17–1.34 (m, 22H), 1.36–1.44 (m, 2H), 1.50–1.58 (m, 2H), 1.63–1.75 (m, 2H), 1.93–1.99 (m, 4H), 2.13–2.24 (m, 2H), 2.84–2.96 (m, 2H), 4.07 (dd, J = 6.2, 12.0 Hz, 1H), 5.26–5.34 (m, 2H), 7.12 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C24H47N2O3 [M+H]+ 411.3581, found: 411.3574.

Oleoyl-L-tyrosine (10).

Compound 10 was prepared from oleoyl chloride and L-tyrosine following the general procedure A as a white solid (23 mg, 70%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.87 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H), 1.19–1.38 (m, 22H), 1.47–1.58 (m, 2H), 1.94–2.04 (m, 4H), 2.07–2.17 (m, 3H), 2.96–3.10 (m, 2H), 4.75 (brs, 1H), 5.29–5.38 (m, 2H), 6.19 (brs, 1H), 6.69 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 6.95 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C27H44NO4 [M+H]+ 446.3265, found: 446.3270.

Oleoyl-L-glutamic acid (11).

Compound 11 was prepared from oleoyl chloride and L-glutamic acid following the general procedure A as a white solid (13 mg, 65%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.88 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 1.19–1.38 (m, 20H), 1.58–1.68 (m, 2H), 1.93–2.07 (m, 4H), 2.08–2.18 (m, 1H), 2.20–2.30 (m, 3H), 2.42–2.60 (m, 2H), 4.65 (dd, J = 6.5, 13.6 Hz, 1H), 5.30–5.38 (m, 2H), 6.53 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 8.23 (brs, 2H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C23H42NO5 [M+H]+ 412.3057, found: 412.3064.

Oleoylglycylglycine (12).

Compound 12 was prepared from oleoyl chloride and 3-aminopropanoic acid following the general procedure A as a white solid (48 mg, 84%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 0.88 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H), 1.25–1.38 (m, 20H), 1.61–1.66 (m, 2H), 1.96–2.04 (m, 6H), 2.25 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 4.08 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 5.29–5.36 (m, 2H), 5.60 (dd, J = 8.0, 4.0 Hz, 4H), 6.03 (brs, 1H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C22H41N2O4 [M+H]+ 397.3061, found: 397.2142.

3-Oleamidopropanoic acid (13).

Compound 13 was prepared from oleoyl chloride and 3-aminopropanoic acid following the general procedure A as a white solid (48 mg, 84%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 0.85 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H), 1.19–1.32 (m, 20H), 1.42–1.49 (m, 2H), 1.96–2.04 (m, 6H), 2.34 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 3.22 (dd, J = 12.0, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 5.29–5.36 (m, 2H), 7.82 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C21H40NO3 [M+H]+ 354.3003, found: 354.3000.

Dodecanoyl-L-phenylalanine (14).

Compound 14 was prepared from dodecanoyl chloride and L-phenyl alanine following the general procedure A as a white solid (45 mg, 89%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 0.86 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H), 1.08–1.31 (m, 16H), 1.34–1.41 (m, 2H), 2.02 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 2.83 (dd, J = 10.2, 13.8 Hz, 1H), 3.05 (dd, J = 4.6, 13.8 Hz, 1H), 4.38–4.44 (m, 1H), 7.17–7.28 (m, 5H), 8.08 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 12.65 (brs, 1H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C21H34NO3 [M+H]+ 348.2533, found: 348.2544.

Palmitoyl-L-phenylalanine (15).

Compound 15 was prepared from palmitoyl chloride and L-phenyl alanine following the general procedure A as a white solid (36 mg, 89%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 0.85 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 1.08–1.31 (m, 24H), 1.35–1.40 (m, 2H), 2.02 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 2.83 (dd, J = 10.0, 13.8 Hz, 1H), 3.04 (dd, J = 4.7, 13.8 Hz, 1H), 4.38–4.44 (m, 1H), 7.17–7.28 (m, 5H), 8.08 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 12.63 (brs, 1H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C25H42NO3 [M+H]+ 404.3159, found: 404.3159

Stearoyl-L-phenylalanine (16).

Compound 16 was prepared from stearoyl chloride and L-phenyl alanine following the general procedure A as a white solid (36 mg, 89%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 0.85 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 1.08–1.31 (m, 28H), 1.33–1.40 (m, 2H), 2.01 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 2.82 (dd, J = 10.0, 13.8 Hz, 1H), 3.04 (dd, J = 4.7, 13.8 Hz, 1H), 4.38–4.44 (m, 1H), 7.16–7.28 (m, 5H), 8.09 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 12.63 (brs, 1H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C27H46NO3 [M+H]+ 432.3472, found: 432.3477.

Icosanoyl-L-phenylalanine (17).

Compound 17 was prepared from icosanoyl chloride and L-phenyl alanine following the general procedure A as a white solid (51 mg, 87%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 0.86 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 3H), 1.09–1.31 (m, 32H), 1.33–1.40 (m, 2H), 2.02 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 2.83 (dd, J = 10.2, 13.8 Hz, 1H), 3.05 (dd, J = 5.3, 14.2 Hz, 1H), 4.38–4.44 (m, 1H), 7.17–7.28 (m, 5H), 8.08 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 12.97 (brs, 1H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C29H50NO3 [M+H]+ 460.3785, found: 460.3796.

Docosanoyl-L-phenylalanine (18).

Compound 18 was prepared from docosanoic acid and L-phenyl alanine following the general procedure B as a white solid (5 mg, 65%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 0.77–0.87 (m, 9H), 1.08–1.42 (m, 22H), 1.43–1.53 (m, 2H), 1.72–1.85 (m, 1H), 1.95–2.02 (m, 4H), 2.06–2.21 (m, 2H), 4.17 (dd, J = 6.2, 8.5 Hz, 1H), 5.28–5.36 (m, 2H), 7.91 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 12.50 (brs, 1H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C31H54NO3 [M+H]+ 488.4098, found: 488.4071.

((9Z,12Z)-Octadeca-9,12-dienoyl)-L-phenylalanine (19).

Compound 19 was prepared from linoleic acid and L-phenyl alanine following the general procedure B as a white solid (35 mg, 75%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 0.86 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 0.98–1.40 (m, 16H), 1.99–2.04 (m, 6H), 2.74 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 3H), 2.86 (dd, J = 7.4, 13.4 Hz, 1H), 3.06 (dd, J = 4.9, 13.4 Hz, 1H), 4.13–4.18 (m, 1H), 5.28–5.38 (m, 4H), 7.10–7.21 (m, 5H), 7.42 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C27H42NO3 [M+H]+ 428.3159, found: 428.3174.

((8Z,11Z,14Z)-Octadeca-8,11,14-trienoyl)-L-phenylalanine (20).

Compound 20 was prepared from (8Z,11Z,14Z)-octadeca-8,11,14-trienoic acid and L-phenyl alanine following the general procedure B as a white solid (13 mg, 70%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.90 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 2.01–2.31 (m, 6H), 1.99–2.04 (m, 6H), 2.77–2.86 (m, 10H), 3.06–3.13 (m, 1H), 3.21–3.29 (m, 1H), 4.70–4.81 (m, 1H), 5.30–5.44 (m, 6H), 5.94 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.16–7.33 (m, 5H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C27H40NO3 [M+H]+ 426.3003, found: 426.3929.

(E)-Octadec-9-enoyl-L-phenylalanine (21).

Compound 21 was prepared from (E)-octadec-9-enoic acid and L-phenyl alanine following the general procedure B as a white solid (67 mg, 80%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.89 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 1.20–1.38 (m, 22H), 1.52–1.62 (m, 2H), 1.92–2.01 (m, 4H), 2.15–2.20 (m, 2H), 3.10–3.29 (m, 2H), 4.87 (dd, J = 7.4, 13.4 Hz, 1H), 5.36–5.44 (m, 2H), 5.96 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.16–7.33 (m, 5H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C27H44NO3 [M+H]+ 430.3316, found: 430.3293

(Z)-Octadec-6-enoyl-L-phenylalanine (22).

Compound 22 was prepared from (Z)-octadec-6-enoic acid and L-phenyl alanine following the general procedure B as a white solid (31 mg, 75%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.89 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 1.20–1.38 (m, 22H), 1.54–1.65 (m, 2H), 1.98–2.04 (m, 4H), 2.17–2.27 (m, 2H), 3.10–3.29 (m, 2H), 4.90 (dd, J = 7.4, 13.4 Hz, 1H), 5.27–5.41 (m, 2H), 6.03 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.16–7.33 (m, 5H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C27H44NO3 [M+H]+ 430.3316, found: 430.3294.

(Z)-Octadec-11-enoyl-L-phenylalanine (23).

Compound 23 was prepared from (Z)-octadec-11-enoic acid and L-phenyl alanine following the general procedure B as a white solid (35 mg, 77%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.89 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 1.20–1.38 (m, 22H), 1.54–1.65 (m, 2H), 1.98–2.04 (m, 4H), 2.17–2.27 (m, 2H), 3.11–3.29 (m, 2H), 4.89 (dd, J = 7.4, 13.4 Hz, 1H), 5.30–5.41 (m, 2H), 6.03 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.16–7.33 (m, 5H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C27H44NO3 [M+H]+ 430.3316, found: 430.3295.

(Z)-Icos-11-enoyl-L-phenylalanine (24).

Compound 24 was prepared from (Z)-icos-11-enoic acid and L-phenyl alanine following the general procedure B as a white solid (30 mg, 73%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.89 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 1.20–1.38 (m, 26H), 1.54–1.65 (m, 2H), 1.98–2.04 (m, 4H), 2.17–2.27 (m, 2H), 3.11–3.28 (m, 2H), 4.90 (dd, J = 7.4, 13.4 Hz, 1H), 5.30–5.41 (m, 2H), 5.99 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.16–7.33 (m, 5H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C29H48NO3 [M+H]+ 458.3629, found: 458.3613.

((5Z,8Z,11Z,14Z)-Icosa-5,8,11,14-tetraenoyl)-L-phenylalanine (25).

Compound 25 was prepared from (5Z,8Z,11Z,14Z)-icosa-5,8,11,14-tetraenoic acid and L-phenyl alanine following the general procedure B as a white solid (10 mg, 71%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.89 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 1.20–1.38 (m, 4H), 1.64–1.70 (m, 2H), 2.02–2.09 (m, 6H), 2.16–2.20 (m, 2H), 2.76–2.84 (m, 6H), 3.11–3.28 (m, 2H), 4.86 (dd, J = 7.4, 13.4 Hz, 1H), 5.25–5.41 (m, 8H), 5.82 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.16–7.33 (m, 5H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C29H42NO3 [M+H]+ 452.3159, found: 452.3341.

((5Z,8Z,11Z,14Z,17Z)-Icosa-5,8,11,14,17-pentaenoyl)-L-phenylalanine (26).

Compound 26 was prepared from (5Z,8Z,11Z,14Z,17Z)-icosa-5,8,11,14,17-pentaenoic acid and L-phenyl alanine following the general procedure B as a white solid (10 mg, 71%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.98 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 1.60–1.67 (m, 2H), 2.01–2.17 (m, 6H), 2.76–2.84 (m, 8H), 3.09–3.26 (m, 2H), 4.82 (dd, J = 7.4, 13.4 Hz, 1H), 5.25–5.41 (m, 10H), 6.02 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.16–7.33 (m, 5H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C29H40NO3 [M+H]+ 450.3003, found: 450.2979.

((4Z,7Z,10Z,13Z,16Z,19Z)-Docosa-4,7,10,13,16,19-hexaenoyl)-L-phenylalanine (27).

Compound 27 was prepared from docosahexaenoic acid and L-phenyl alanine following the general procedure B as a white solid (5 mg, 65%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.97 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 1.22–1.40 (m, 10HHHH) 1.52–1.62 (m, 2H), 2.02–2.09 (m, 4H), 2.19 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 2.81 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 4H) 3.11–3.29 (m, 2H), 4.89 (dd, J = 8.0, 16 Hz, 1H), 5.22–5.44 (m, 12H), 5.98–6.10 (m, 1H), 7.10–7.24 (m, 5H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C31H40NO3Na [M+Na]+ 498.2979, found: 498.2979.

(Z)-(Octadec-9-en-1-ylcarbamoyl)glycine (28).

Compound 28 was prepared from intermediate 43 and glycine methyl ester following the general procedure C as a white solid (5 mg, 94%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.89 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 1.20–1.38 (m, 22H), 1.59–1.67 (m, 2H), 1.97–2.06 (m, 4H), 2.34–2.38 (m, 1H), 3.13–3.21 (m, 1H), 3.47–3.54 (m, 2H), 3.95–4.05 (m, 1H), 5.32–5.38 (m, 2H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C21H41N2O3 [M+H]+ 369.3112, found: 369.3098.

(Z)-(Octadec-9-en-1-ylcarbamoyl)-L-phenylalanine (29).

Compound 29 was prepared from intermediate 43 and L-phenyl alanine methyl ester following the general procedure C as a white solid (9 mg, 96%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.89 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 1.20–1.38 (m, 22H), 1.43–1.51 (m, 2H), 1.95–2.06 (m, 4H), 2.84–2.90 (m, 1H), 3.24–3.29 (m, 1H), 3.36–3.46 (m, 2H), 4.22–4.25 (m, 1H), 5.31–5.38 (m, 2H), 5.62 (brs, 1H), 7.19–7.35 (m, 5H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C28H47N2O3 [M+H]+ 459.3581, found: 459.3554.

(S)-1-Oleoylpiperidine-2-carboxylic acid (30).

Compound 30 was prepared from oleoyl chloride and (S)-piperidine-2-carboxylic acid following the general procedure A as a white solid (35 mg, 82%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.81 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H), 1.09–1.31 (m, 20H), 1.43–1.51 (m, 2H), 1.63–1.70 (m, 4H), 1.86–2.01 (m, 4H), 2.22–2.23 (m, 2H), 2.26–2.33 (m, 2H), 3.13–3.20 (m, 2H), 3.68–3.72 (m, 2H), 4.48–4.53 (m, 1H), 5.24–5.33 (m, 2H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C24H44NO3 [M+H]+ 394.3316, found: 394.3298.

(S)-2-Oleoyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxylic acid (31).

Compound 31 was prepared from oleoyl chloride and (S)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxylic acid following the general procedure A as a white solid (25 mg, 78%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.90 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H), 1.09–1.31 (m, 22H), 1.63–1.70 (m, 2H), 2.01–2.08 (m, 4H), 2.46–2.51 (m, 2H), 3.09–3.15 (m, 1H), 3.27–3.38 (m, 1H), 4.61–4.71 (m, 2H), 5.35–5.42 (m, 2H), 7.12–7.26 (m, 4H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C28H44NO3 [M+H]+ 442.3316, found: 442.3292.

2-Oleoyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-1-carboxylic acid (32).

Compound 32 was prepared from oleoyl chloride and 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-1-carboxylic acid following the general procedure A as a white solid (40 mg, 86%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.90 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H), 1.09–1.31 (m, 22H), 1.63–1.70 (m, 2H), 2.01–2.08 (m, 4H), 2.46–2.51 (m, 2H), 3.09–3.15 (m, 1H), 3.27–3.38 (m, 1H), 4.61–4.71 (m, 2H), 5.35–5.42 (m, 2H), 7.12–7.26 (m, 4H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C28H44NO3 [M+H]+ 442.3316, found: 442.3291.

(S)-2-Oleoylisoindoline-1-carboxylic acid (33).

Compound 33 was prepared from oleoyl chloride and (S)-isoindoline-1-carboxylic acid following the general procedure A as a white solid (1.1 g, 81%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.88 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H), 1.09–1.47 (m, 22H), 1.64–1.76 (m, 2H), 1.94–2.08 (m, 4H), 2.26–2.51 (m, 2H), 3.09–3.15 (m, 1H), 4.78–4.96 (m, 2H), 5.30–5.42 (m, 2H), 5.69 (s, 1H), 7.26–7.52 (m, 4H), 9.16 (brs, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.5, 173.0, 136.5, 134.3, 130.0, 129.8, 128.9, 128.3, 123.8, 122.7, 65.1, 52.7, 34.2, 31.9, 29.8, 29.7, 29.5, 29.3, 29.2, 27.2, 24.5, 22.7, 14.1. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C27H44NO3 [M+H]+ 428.3159, found: 428.3136.

(R)-2-Oleoylisoindoline-1-carboxylic acid (34).

Compound 34 was prepared from oleoyl chloride and (R)-isoindoline-1-carboxylic acid following the general procedure A as a white solid (45 mg, 73%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.89 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H), 1.21–1.44 (m, 22H), 1.68–1.76 (m, 2H), 1.96–2.08 (m, 4H), 2.45–2.51 (m, 2H), 3.09–3.15 (m, 1H), 4.78–4.96 (m, 2H), 5.30–5.42 (m, 2H), 5.75 (s, 1H), 7.26–7.52 (m, 4H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C27H44NO3 [M+H]+ 428.3159, found: 428.3141.

(S)-1-Oleoylindoline-2-carboxylic acid (35).

Compound 35 was prepared from oleoyl chloride and (S)-indoline-2-carboxylic acid following the general procedure A as a white solid (37 mg, 77%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.89 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H), 1.22–1.45 (m, 22H), 1.68–1.82 (m, 2H), 1.96–2.08 (m, 4H), 2.29–2.42 (m, 1H), 2.66–2.80 (m, 1H), 3.28–3.33 (m, 1H), 3.41–3.67 (m, 1H), 4.93–5.21 (m, 1H), 5.30–5.42 (m, 2H), 7.01–7.26 (m, 4H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C27H44NO3 [M+H]+ 428.3159, found: 428.3142.

(S)-2-((9Z,12Z)-Octadeca-9,12-dienoyl)isoindoline-1-carboxylic acid (36).

Compound 36 was prepared from linoleic acid and (S)-isoindoline-1-carboxylic acid following the general procedure B as a white solid (35 mg, 75%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.89 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H), 1.17–1.43 (m, 18H), 1.56–1.75 (m, 2H), 1.98–2.10 (m, 4H), 2.25–2.49 (m, 2H), 2.74–2.81 (m, 2H), 4.81–4.97 (m, 2H), 5.30–5.42 (m, 2H), 5.72 (s, 1H), 7.27–7.55 (m, 4H). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C27H40NO3 [M+H]+ 426.3003, found: 426.2982.

(R)-2-((9Z,12Z)-Octadeca-9,12-dienoyl)isoindoline-1-carboxylic acid (37).

Compound 37 was prepared from linoleic acid and (R)-isoindoline-1-carboxylic acid following the general procedure B as a white solid (1.2 g, 74%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.89 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H), 1.23–1.43 (m, 18H), 1.67–1.75 (m, 2H), 2.00–2.10 (m, 4H), 2.25–2.49 (m, 2H), 2.74–2.81 (m, 2H), 4.81–4.97 (m, 2H), 5.30–5.42 (m, 2H), 5.72 (s, 1H), 7.27–7.55 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.5, 173.2, 136.5, 134.3, 130.2, 130.1, 128.9, 128.0, 127.9, 123.8, 122.7, 65.0, 52.7, 34.2, 31.5, 29.6, 29.4, 29.3, 29.2, 27.2, 25.7, 24.5, 22.6, 14.1. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C27H40NO3 [M+H]+ 426.3003, found: 426.2981.

Measurement of cellular respiration.

Oligomycin was purchased from EMD Millipore, and FCCP and rotenone were purchased from Sigma. C2C12 cells were seeded at 35,000 cells/well in an XF24 cell culture microplate (V7-PS, Seahorse Bioscience) and analyzed the following day. On the day of analysis, the cells were washed once with Seahorse respiration buffer (8.3 g/l DMEM, 1.8 g/l NaCl, 1 mM pyruvate, 20 mM glucose, pen/strep), placed in 0.5 ml Seahorse respiration buffer, and incubated in a CO2-free incubator for 1 h. Port injection solutions were prepared as follows (final concentrations in assay in parentheses): 10 μM oligomycin (1 μM final), 500 μM indicated compound (50 μM final), 2 μM FCCP (0.2 μM final), and 30 μM rotenone (3 μM final). The Seahorse program was run as follows: basal measurement, 3 cycles; inject port A (oligomycin), 3 cycles; inject port B (compounds), 8 cycles; inject port C (FCCP), 3 cycles; inject port D (rotenone), 3 cycles. Each cycle consisted of mix 2 min, wait 0 min, and measure 2 min. For data expressed as a percentage of oligomycin-treated basal, the respiration at cycle 6 was normalized to 100%, and the maximum respiration at any time point between cycles 7 and 15 inclusive was used.

Generation of recombinant PM20D1.

Three 10cm plates of 293T cells were transiently transfected with murine PM20D1–6xHis-Flag plasmid (Addgene plasmid #84566) using PolyFect according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 48 h, cells were washed twice in PBS and switched to serum free DMEM with penicillin and streptomycin. Serum free conditioned media was collected 24 h later and concentrated ~10-fold in 30 kDa MWCO filters (EMD Millipore) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentrated media was centrifuged to remove debris (600 × g, 10 min, 4°C) and the supernatant containing PM20D1-flag was decanted into a new tube. PM20D1-flag was immunoaffinity purified overnight at 4°C from the concentrated media using magnetic Flag-M2 beads (Sigma Aldrich). The beads were collected, washed three times in PBS, eluted with 3xFlag peptide (0.1 μg/ml in PBS, Sigma Aldrich), aliquoted, and stored at −80°C.

PM20D1 hydrolysis assays.

10 nmol of the indicated compound was incubated in 100 μl PBS (100 μM initial substrate). Reactions were initiated by the addition of PBS or mPM20D1 (5 μl). After 1 h at 37ºC, reactions were quenched with 600 μl of a 2:1 v/v mixture of chloroform and methanol with 10 nmol d31-palmitate as an internal standard. The reactions were vortexed and the organic layer was transferred to a sample vial for analysis by LC-MS. For separation of polar metabolites, normal-phase chromatography was performed with a Luna-5 mm NH2 column (50 mm × 4.60 mm, Phenomenex). Mobile phases were as follows: Buffer A, acetonitrile; Buffer B, 95:5 water/ acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid or 0.2% ammonium hydroxide with 50 mM ammonium acetate for positive and negative ionization mode, respectively. The flow rate for each run started at 0.2 ml/min for 2 min, followed by a gradient starting at 0% B and increasing linearly to 100% B over the course of 15 min with a flow rate of 0.7 ml/min, followed by an isocratic gradient of 100% B for 10 min at 0.7 ml/min before equilibrating for 5 min at 0% B with a flow rate of 0.7 ml/min. MS analysis was performed with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source on an Agilent 6430 QQQ LC−MS/MS. The capillary voltage was set to 3.5 kV, and the fragmentor voltage was set to 100 V. The drying gas temperature was 325 °C, the drying gas flow rate was 10 l/min, and the nebulizer pressure was 45 psi. Monitoring of hydrolysis starting materials and products was performed by scanning a mass range of m/z 50–1200. Peaks corresponding to the liberated fatty acids (products) or the intact starting material was integrated.

Liver microsome stability assays.

Microsome stability was evaluated by incubating 1 μM test compound with 1 mg/mL hepatic microsomes in 100 mM KPi, pH 7.4 at 37C with shaking. The reaction was initiated by adding NADPH (1 mM final concentration). Aliquots were removed at 0, 5, 10, 20, 40, and 60 minutes and added to acetonitrile (5X v:v) to stop the reaction and precipitate the protein. NADPH dependence of the reaction was evaluated with -NADPH samples. At the end of the assay, the samples were centrifuged through a Millipore Multiscreen Solvinter 0.45 micron low binding PTFE hydrophilic filter plate and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Data is log transformed and represented as half-life.

Treatment of mice with compounds.

DIO mice (19 weeks, males, stock #380050) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Mice were maintained on high fat diet for the duration of the experiment (60% fat, Research Diets). Prior to compound administration, mice were mock injected with vehicle (18:1:1 v/v/v saline:DMSO:Kolliphor EL) for 4 days. Compound 37 was prepared in the same vehicle and administered at 5 μl/g body weight at the indicated doses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (DK31405, B.M.S.; DK105203, J.Z.L.; K99DK111916, K.J.S.).

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- DCM

dichloromethane

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- HRMS

high resolution mass spectrometry

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- SAR

structure−activity relationship

- TLC

thin-layer chromatography

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS

Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.

HPLC analysis results of target compounds (PDF)

Molecular formula strings with biological data (CSV)

REFERENCES

- 1.Connor M; Vaughan CW; Vandenberg RJ, N-acyl amino acids and N-acyl neurotransmitter conjugates: neuromodulators and probes for new drug targets. British journal of pharmacology 2010, 160 (8), 1857–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smoum R; Bar A; Tan B; Milman G; Attar-Namdar M; Ofek O; Stuart JM; Bajayo A; Tam J; Kram V; O’Dell D; Walker MJ; Bradshaw HB; Bab I; Mechoulam R, Oleoyl serine, an endogenous N-acyl amide, modulates bone remodeling and mass. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2010, 107 (41), 17710–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang SM; Bisogno T; Petros TJ; Chang SY; Zavitsanos PA; Zipkin RE; Sivakumar R; Coop A; Maeda DY; De Petrocellis L; Burstein S; Di Marzo V; Walker JM, Identification of a new class of molecules, the arachidonyl amino acids, and characterization of one member that inhibits pain. The Journal of biological chemistry 2001, 276 (46), 42639–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu J; Zhu C; Yang L; Wang Z; Wang L; Wang S; Gao P; Zhang Y; Jiang Q; Zhu X; Shu G, N-Oleoylglycine-Induced Hyperphagia Is Associated with the Activation of Agouti-Related Protein (AgRP) Neuron by Cannabinoid Receptor Type 1 (CB1R). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65 (5), 1051–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raboune S; Stuart JM; Leishman E; Takacs SM; Rhodes B; Basnet A; Jameyfield E; McHugh D; Widlanski T; Bradshaw HB, Novel endogenous N-acyl amides activate TRPV1–4 receptors, BV-2 microglia, and are regulated in brain in an acute model of inflammation. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oh DY; Yoon JM; Moon MJ; Hwang JI; Choe H; Lee JY; Kim JI; Kim S; Rhim H; O’Dell DK; Walker JM; Na HS; Lee MG; Kwon HB; Kim K; Seong JY, Identification of farnesyl pyrophosphate and N-arachidonylglycine as endogenous ligands for GPR92. The Journal of biological chemistry 2008, 283 (30), 21054–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan B; O’Dell DK; Yu YW; Monn MF; Hughes HV; Burstein S; Walker JM, Identification of endogenous acyl amino acids based on a targeted lipidomics approach. Journal of lipid research 2010, 51 (1), 112–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Long JZ; Svensson KJ; Bateman LA; Lin H; Kamenecka T; Lokurkar IA; Lou J; Rao RR; Chang MR; Jedrychowski MP; Paulo JA; Gygi SP; Griffin PR; Nomura DK; Spiegelman BM, The Secreted Enzyme PM20D1 Regulates Lipidated Amino Acid Uncouplers of Mitochondria. Cell 2016, 166 (2), 424–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hermesh O; Kalderon B; Bar-Tana J, Mitochondria uncoupling by a long chain fatty acyl analogue. The Journal of biological chemistry 1998, 273 (7), 3937–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devane WA; Hanus L; Breuer A; Pertwee RG; Stevenson LA; Griffin G; Gibson D; Mandelbaum A; Etinger A; Mechoulam R, Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science (New York, N.Y.) 1992, 258 (5090), 1946–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cutting WC; Mehrtens HG; Tainter ML, Actions and Uses of Dinitrophenol- Promising Metabolic Applications. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 1933, 101 (3), 193–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldgof M; Xiao C; Chanturiya T; Jou W; Gavrilova O; Reitman ML, The chemical uncoupler 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) protects against diet-induced obesity and improves energy homeostasis in mice at thermoneutrality. The Journal of biological chemistry 2014, 289 (28), 19341–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]