Abstract

Two experiments investigated methods that reduce the resurgence of an extinguished behavior (R1) that occurs when reinforcement for an alternative behavior (R2) is discontinued. In Experiment 1, R1 was first trained and then extinguished while R2 was reinforced during a 5-or 25-session treatment phase. For half the rats, sessions in which R2 was reinforced alternated with sessions in which R2 was extinguished. Controls received the same number of treatment sessions, but R2 was never extinguished. When reinforcement for R2 was discontinued, R1 resurged in the controls. However, the alternating groups showed reduced resurgence, and the magnitude of the resurgences observed during their R2 extinction sessions decreased systematically over Phase 2. In Experiment 2, R1 was first reinforced with one outcome (O1). The rats then had two types of double-alternating treatment sessions. In one type, R1 was extinguished and R2 produced O2. In the other, R1 was unavailable and R2 produced O3. R1 resurgence was weakened when O2, but not O3, was delivered freely during testing. Together, the results suggest that methods that encourage generalization between R1 extinction and resurgence testing weaken the resurgence effect. They are not consistent with an account of resurgence proposed by Shahan and Craig (2017).

Keywords: resurgence, extinction, relapse prevention, context, generalization

In resurgence, an extinguished operant behavior recovers when reinforcement for an alternative second behavior is removed (Leitenberg, Rawson, & Bath, 1970). In a typical experimental design, a target behavior (R1) is acquired in an initial phase, then extinguished in a second phase while a newly available response (R2) is reinforced. When R2 is subsequently extinguished, R1 behavior returns or “resurges.” Resurgence is a robust effect that occurs under a variety of conditions, including when R2 is reinforced on fixed ratio (FR) or variable interval (VI) schedules and when the topography of the response differs between R1 and R2 (Leitenberg, Rawson, & Mulick, 1975). Resurgence occurs when R1 behavior is reinforced by food (Leitenberg et al., 1970), cocaine (Quick, Pyszczynski, Colston, & Shahan, 2011), or alcohol (Podlesnik, Jiminez-Gomez, & Shahan, 2006). Moreover, the behavior that resurges seems to resemble that which was originally trained in sequence (Reed & Morgan, 2006), response pattern (Cançado & Lattal, 2011), and response rate (Winterbauer, Lucke, & Bouton, 2013).

Several factors are known to influence the magnitude of resurgence. In general, higher rates of R2 reinforcement result in more resurgence than leaner rates (e.g., Bouton & Trask, 2016; Leitenberg et al., 1975; Sweeney & Shahan, 2013a). Making the reinforcement rate progressively leaner throughout Phase 2 (i.e., “thinning” the rate) reduces resurgence (Sweeney & Shahan, 2013a; Winterbauer & Bouton, 2012), and a “reverse thinning” procedure (in which reinforcement rates start low at the beginning of Phase 2 and then progressively increase) has a similar effect (Bouton & Schepers, 2014; Schepers & Bouton, 2015). Additionally, periods of nonreinforcement introduced during Phase 2 can reduce resurgence relative to a group receiving consistent reinforcement at the same average rate (Schepers & Bouton, 2015).

Several theories of resurgence have been proposed. One account handles the existing data by assuming that the principles that govern other forms of relapse (e.g., renewal, reinstatement, spontaneous recovery) also govern resurgence. Specifically, resurgence may be another phenomenon that demonstrates that extinguished behavior returns when the context is changed (e.g., Trask, Schepers, & Bouton, 2015; Winterbauer & Bouton, 2010). The best-known example of this principle is the renewal effect. In renewal, the animal acquires a response in one context (Context A). Responding is subsequently extinguished in a second context, Context B, that usually differs in distinct tactile, visual, and olfactory properties. When responding is tested back in the original context or in a new context (i.e., Context C), responding renews. The context account of resurgence suggests that resurgence is a special case of the “ABC” renewal effect in which the contexts are created by the presence or absence of reinforcement: Reinforcement for R1 creates Context A, reinforcement for R2 creates Context B, and the nonreinforcement conditions during testing change the context to a new Context C. The approach follows from a long tradition in learning theory that emphasizes the discriminative properties of reinforcers, including those delivered during extinction (e.g., Bouton, Rosengard, Achenbach, Peck, & Brooks, 1993; Ostlund & Balleine, 2007; Reid, 1958; Rescorla & Skucy, 1969). The explanation predicts that procedures that encourage generalization from the context of R1 extinction to the context of testing will reduce the resurgence effect.

Another recent approach to resurgence is the Resurgence as Choice (RaC) model proposed by Shahan and Craig (2017). The model uses the matching law’s (e.g., Herrnstein, 1961) suggestion that relative response rates allocated to two response options will approximate the relative rates of reinforcement delivered for each response option. RaC essentially states that, in Phase 2 of a resurgence paradigm, the value of the response that has been historically effective (R1) is compared to the value of the currently effective response, R2. R1’s value decreases across Phase 2 because it is now nonreinforced and time is increasing since it was last reinforced. However, its value never reaches zero. Meanwhile, R2’s value increases as it is reinforced during Phase 2, and alternative (R2) responding therefore prevails. During the resurgence test, the value of R2 decreases rapidly when it is extinguished, which increases the relative value of R1. R1 therefore resurges. (There is a recency rule such that the value of R2 drops more precipitously during the resurgence test than does the value of R1 that has remained through extinction.) The model accounts for the basic resurgence effect as well as several aspects of resurgence, including at least some of the findings noted above, such as weaker resurgence after lean Phase-2 reinforcement and after procedures that thin the rate of reinforcement as Phase 2 progresses (see Shahan & Craig, 2017, for a complete discussion).

As acknowledged by Shahan and Craig (2017), however, the RaC model cannot account for several important but potentially controversial results. For example, Schepers and Bouton (2015, Experiment 3) gave three groups different treatments during Phase 2. For all groups, R1 was extinguished. For one group, R2 produced reinforcers on a VI 10-s schedule in every session. For a second group, R2 produced reinforcers on a VI 10-s schedule during odd-numbered sessions (1, 3, 5, and 7), but none during even-numbered sessions (2, 4, and 6). Thus, this group alternated between sessions of R2 reinforcement and R2 extinction. A third group received a consistent rate of reinforcement over sessions that equaled the average rate of the alternating group (a VI 17.5-s schedule). During a resurgence test, extinction was in effect for both responses for all groups. Simulations of this experiment with the RaC model (Shahan & Craig, p. 116) explicitly predict no difference in resurgence between the latter two groups. However, this was not the obtained result. Instead, while both the VI 10-s and VI 17.5-s groups showed similar levels of resurgence, resurgence in the alternating group was reduced. Shahan and Craig pointed to ostensibly discrepant findings from an experiment conducted in their laboratory with non-naive pigeon subjects (Sweeney & Shahan, 2013b, Experiment 2). In that experiment, no difference was observed in a final resurgence test after either constant or alternating R2 reinforcement in Phase 2. However, there was little resurgence in the control condition (although it was not statistically evaluated). This suggested a possible floor effect (as noted by the authors) that may make the lack of difference between conditions difficult to interpret. The context explanation suggests that experience with the testing conditions (i.e., extinction of both R1 and R2) during Phase 2 caused response inhibition to generalize better from extinction to the test in the experiment reported by Schepers and Bouton (2015). We therefore examined the hypothesis again under new conditions in the present Experiment 1.

A second result that is not consistent with the RaC model was reported by Bouton and Trask (2016, Experiment 2). In that experiment, R1 was first reinforced with a distinct O1 reinforcer (either a sucrose-or grain-based pellet, counterbalanced). In a second phase, R1 was extinguished while R2 was reinforced with the other reinforcer (O2). During the test, both R1 and R2 were extinguished. For one group, nothing else occurred. This was a standard resurgence control group in which resurgence was expected. For a second group, O2 reinforcers were delivered not contingent on responding at the rate they had been earned in Phase 2. A third group received the same treatment with O1. According to the RaC model, keeping a consistent reinforcement rate between Phase 2 and Phase 3 with either O1 or O2 might reduce resurgence because either reinforcer could keep the value of R2 high. The model would assume that this could occur through a “misallocation process” in which noncontingent reinforcers would be misattributed to R2, thus maintaining the value of R2 (Shahan & Craig, 2017, see pp. 119 and 121). However, despite their identical delivery rate in Bouton and Trask’s experiment, only O2 abolished resurgence; resurgence in the O1 group was unaffected. RaC does not account for that result because it gives no role to the discriminative properties of the reinforcers. The context account contrastingly predicts the obtained result by noting that O2 presentations, but not O1 presentations, maintained a key feature of Phase 2 and therefore encouraged generalization from treatment to testing.

Given the importance of the two results just described, the current experiments were designed to replicate, refine, and expand on them. Experiment 1 used methods similar to those of Schepers and Bouton (2015, Experiment 3) to more thoroughly analyze how alternating sessions of R2 reinforcement and extinction affects resurgence over a more prolonged treatment phase. The value of such an experiment was actually suggested by Shahan and Craig (2017, p. 118). Experiment 2 then used a new procedure to further examine the prediction that the reinforcer that was specifically present during extinction of R1 can suppress the resurgence effect (as in Bouton & Trask, 2016, Experiment 2).

Experiment 1

The first experiment employed the usual three-phase resurgence design. After a phase in which R1 was reinforced, animals received sessions in which R1 was extinguished while a new R2 was reinforced. Animals were assigned to groups that either received constant reinforcement for R2 throughout the phase (on a random-interval 10-s schedule) or alternating sessions in which R2 was reinforced and extinguished. Groups either received a long (25-day) or short (5-day) Phase 2 treatment. The context hypothesis predicts that animals in the alternating groups will have reduced resurgence on a final test day relative to their respective controls, because they uniquely had an opportunity to learn to inhibit R1 in the context of nonreinforcement of R2. Moreover, the magnitude of the individual resurgences (evident on the Phase-2 sessions when R2 was extinguished) was expected to decrease over sessions as the animals learned. Neither of these predictions is made by the RaC model, which instead predicts that resurgence should not differ between constant and alternating groups on the final test day (Shahan & Craig, 2017, p. 116); since R2 was reinforced for both groups in the final session of Phase 2, R2’s value is expected to be comparable at the start of testing. The model also predicts that individual resurgences will be of the same magnitude on each extinction session in the alternating group (see Shahan & Craig, 2017, pp. 116–118).

Method

Subjects.

The subjects were 32 naïve female Wistar rats (eight per group) purchased from Charles River Laboratories (St. Constance, Quebec), aged 75–90 days at the start of the experiment. They were individually housed in suspended wire mesh cages and maintained on a 16:8-hr light:dark cycle. Training sessions occurred during the light phase. Rats were food-deprived to 80% of their initial weights throughout the experiment.

Apparatus.

Conditioning proceeded in two sets of four standard conditioning boxes (ENV-008-VP: Med-Associates, St. Albans, VT) that were housed in different rooms of the laboratory. Boxes from both sets measured 31.75 × 24.13 × 29.21 cm (l × w × h) and were housed in sound-attenuation chambers. The boxes were the chambers used by Schepers and Bouton (2015) and are described in more detail there. Retractable levers were positioned to the right and left of the recessed food cup, which was centered in the wall of the intelligence panel. Although the two sets of boxes can provide different contexts, they were not used in that capacity here. The reinforcer was a 45-mg MLab Rodent Tablet (5-TUM: 181156; TestDiet, Richmond, IN).

Procedure.

Daily sessions were employed throughout the experiment. Each day’s session began with approximately 9 hr of illuminated colony time remaining. Animals were placed in the conditioning chambers, and the start of each session was announced by insertion of the appropriate lever(s). All sessions were 30 min in duration and ended with retraction of the lever(s). The day on which the first session (magazine training) occurred for Group Short was delayed so that testing occurred on the same day for all groups. Thus, on the final test, rats in the two groups were the same age, had been under food deprivation for the same number of days, and had received the same amount of handling overall.

Magazine training.

All animals first received a session of magazine training. While both levers were retracted, approximately 60 food pellets were delivered to the food cup on a random time 30-s (RT 30-s) schedule of reinforcement; delivery occurred with a uniformly distributed 1 in 30 probability in each second.

R1 acquisition (Phase 1).

Beginning the next day, all animals then received 12 sessions of instrumental training initiated by the insertion of the R1 lever (counterbalanced as the left or right lever for half the animals). Presses on this lever delivered a food pellet on a random interval 30-s (RI 30-s) schedule of reinforcement. No additional response shaping was necessary.

R1 extinction and R2 acquisition (Phase 2).

All animals then received Phase 2 sessions. The Long group received 25 such sessions (days 1 – 25 of the phase) whereas the Short group received 5 (on days 21 – 25). In these sessions, R1 responding had no programmed consequences (it was extinguished). For Groups Long Constant and Short Constant, responding on a newly-inserted second lever (R2; counterbalanced as the right or left) produced food pellets on a RI 10-s schedule. Group Long Alternating and Group Short Alternating had a similar treatment on odd-numbered sessions, but R2 was extinguished (had no programmed consequences) on even-numbered sessions (sessions 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, and 24 for Group Long Alternating and sessions on days 22 and 24 for Group Short Alternating). Both levers were inserted in the chamber throughout each session.

Final resurgence test (Phase 3).

On the day following the conclusion of Phase 2, all rats received one 30-min test session in which both levers were inserted but responses on neither were reinforced.

Data analysis.

Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used to assess response rates throughout the experiment. The rejection criterion was p < .05. Partial eta squared was reported where appropriate as a measure of effect size.

Results

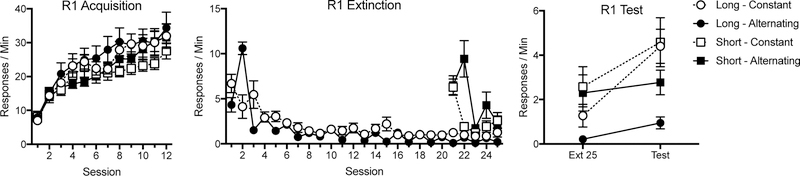

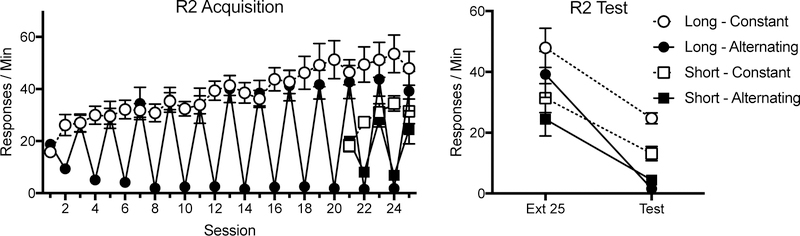

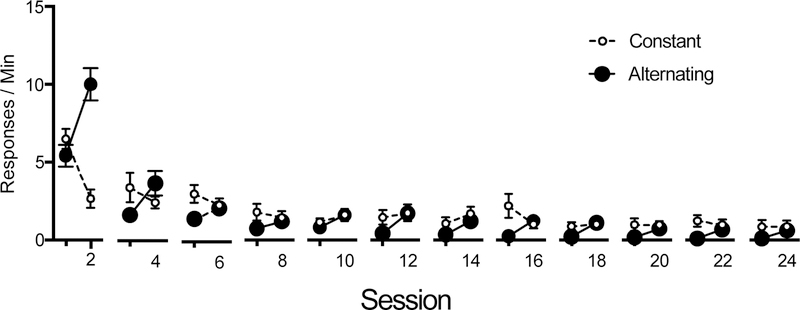

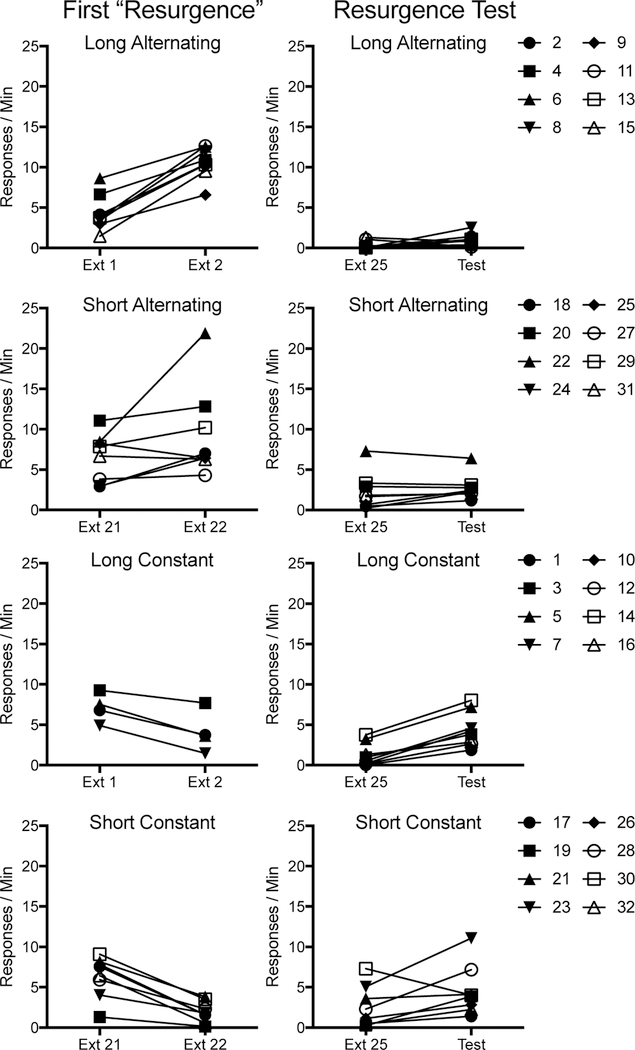

The results of Experiment 1 are presented in Figure 1 (R1 responding), Figure 2 (R2 responding), Figure 3 (R1 resurgences for the constant and alternating groups across Phase 2), and Figure 4 (data for individual subjects from the first [left panels] and final [right panels] opportunities to observe resurgence). In the first phase, all animals increased R1 responding. In Phase 2, R2 performance generally increased for all animals. In both alternating groups, R2 responding was low in sessions when it was not reinforced, while R1 responding showed resurgence. The R1 increases representing resurgence, however, decreased in magnitude over the phase. During the final test, both alternating groups showed reduced resurgence relative to their constant controls.

Fig. 1.

Mean R1 responding during the three phases of Experiment 1. R1 acquisition (Phase 1) is depicted in the left panel, R1 Extinction (Phase 2) in the center panel, and R1 Test in the right panel. Error bars represent SEM. Note changes in y axes.

Fig. 2.

Mean R2 responding throughout Experiment 1. R2 acquisition (Phase 2) is depicted in the left panel and R2 Test in the right panel. Error bars represent SEM. Note changes in y axes.

Fig. 3.

Mean R1 responding during the treatment phase (Phase 2) for all groups in Experiment 1. The second session in each panel involved extinction of R2 in the alternating groups. Note that R1 initially showed strong resurgence, and that the strength of that effect then decreased systematically over the phase. To capitalize on all the data available, Groups Long and Short are combined in the first two panels; Group Long remains in the following 10 panels.

Fig. 4.

Individual subject data from Experiment 1. The first resurgence (left panels; Sessions 1 – 2 for Group Long, Sessions 21 – 22 for Group Short) and from the final resurgence test for all groups (right panels) can be compared.

Phase 1.

R1 acquisition.

A 2 (Duration: Long vs. Short) x 2 (Condition: Constant vs. Alternating) x 12 (Session) ANOVA conducted on R1 responding throughout R1 acquisition (Fig. 1) revealed a main effect of session, F (1, 28) = 70.92, MSE = 19.65, p < .001, ηp2 = .72. No other main effects or interactions were significant, largest F = 2.38, p = .14.

Phase 2.

R1 extinction (Group Long).

R1 extinction for both groups is shown in the middle panel of Figure 1. Due to an equipment failure, no data were recorded for four animals from Group Long Constant on day 2. These rats were therefore not included in the statistical analysis of extinction, although their data from the unaffected days are included in the means displayed in Figures 1 and 2 (their performance was consistent with that of the other animals). A 2 (Condition: Constant vs. Alternating) x 25 (Session) ANOVA conducted on R1 responding throughout this phase found a main effect of session, F (24, 240) = 33.22, MSE = 0.80, p < .001, ηp2 = .77, and an interaction, F (24, 240) = 9.96, MSE = 0.80), p < .001, ηp2 = .50, but no effect of condition, F (1, 10) = 1.76, p = .21. In order to assess changes in individual resurgences throughout the Phase, a 2 (Session: Odd-numbered to Even-numbered) x 2 (Condition: Constant vs. Alternating) x 12 (Cycle) ANOVA was run on R1 responding. This found a main effect of cycle, F (11, 110) = 46.30, MSE = 1.17, p < .001, ηp2 = .82, and a marginal effect of session, F (1, 10) = 3.76, MSE = 1.95, p = .08, ηp2 = .27. There was a cycle by condition interaction, F (11, 110) = 3.17, MSE = 1.17, p = .001, ηp2 = .001, ηp2 = .24, a session by condition interaction, F (1, 10) = 28.96, MSE = 1.95, p < .001, ηp2 = .74, a cycle by session interaction, F (11, 110) = 4.80, MSE = 0.37, p < .001, ηp2 = .32, and a crucial significant cycle by session by condition interaction, F (11, 110) = 22.89, MSE = .37, p < .001, ηp2 = .70. The latter result suggests that the magnitude of the resurgence effect decreased across successive resurgences. No main effect of condition was found, F = 1.64, p = .23. The decreasing size of the resurgence effects observed over Phase 2 is highlighted in Figure 3.

It is possible that the significant cycle by session by condition interaction emphasized above was a result of comparing changes in response rate when response rates differed substantially on the response-rate scale. For example, it is possible that responding in the range of higher response rates is somehow more sensitive to detecting resurgence effects. We therefore ran a similar ANOVA after first excluding the first cycle (sessions 1 and 2), where R1 responding was especially high. This additional analysis found a main effect of cycle, F (10, 140) = 15.74, MSE = 1.21, p < .001, ηp2 = .53, a marginal effect of session, F (1, 14) = 4.44, MSE = 1.22, p = .054, ηp2 = .24, a marginal effect of condition, F (1, 14) = 4.51, MSE = 9.47, p = .052, ηp2 = .24, a cycle by session interaction, F (10, 140) = 1.97, MSE = 0.65, p < .05, ηp2 = .12, and a session by condition interaction, F (1, 14) = 23.72, MSE = 1.22, p < .001, ηp2 = .63. Importantly, the crucial session by condition by cycle interaction remained significant, F (10, 140) = 3.69, MSE = 0.65, p < .001, ηp2 = .21. No other effects or interactions were significant, largest F = 1.42, p = .18.

R1 extinction (Group Short).

A 2 (Condition: Constant vs. Alternating) x 5 (Session) ANOVA was run to assess R1 responding in Group Short. This found a main effect of session, F (4, 56) = 18.08, MSE = 3.98, p < .001, ηp2 = .56, a marginal effect of condition, F (1, 14) = 3.24, MSE = 26.25, p = .09, ηp2 = .19, and a significant interaction, F (4, 56) = 10.32, MSE = 3.98, p < .001. As before, a 2 (Session: Odd-numbered to Even-numbered) x 2 (Condition: Constant vs. Alternating) x 2 (Cycle) ANOVA was run to assess changes in individual resurgences across the phase in the short groups. This revealed a main effect of condition, F (1, 14) = 5.09, MSE = 21.99, p < .05, ηp2 = .27, a main effect of cycle, F (1, 14) = 45.98, MSE = 4.88, p < .001, ηp2 = .77, a cycle by condition interaction, F (1, 14) = 4.81, MSE = 4.88, p < .05, ηp2 = .26, a session by condition interaction, F (1, 14) = 10.03, MSE = 8.40, p < .01, ηp2 = .42, a cycle by session interaction, F (1, 14) = 23.15, MSE = 0.96, p < .001, ηp2 = .62, and a crucial cycle by session by condition interaction, F (1, 14) = 30.64, MSE = 0.96, p < .001, ηp2 = .69. The latter result again suggests that the magnitude of the resurgence effect decreased over periods of R2 nonreinforcement. No main effect of session was found, F < 1.

R2 acquisition (Group Long).

R2 responding throughout the experiment is shown in Figure 2. A 2 (Condition: Constant vs. Alternating) x 25 (Session) ANOVA examined R2 responding in Group Long during acquisition. This found a main effect of session, F (24, 240) = 17.43, MSE = 78.27, p < .001, ηp2 = .64, condition, F (1, 10) = 12.21, MSE = 2568.33, p < .01, ηp2 = .55, and an interaction, F (24, 240) = 14.28, MSE = 78.27, p <.001, ηp2 = .59.

R2 acquisition (Group Short).

A 2 (Condition: Constant vs. Alternating) x 5 (Session) ANOVA assessed R2 responding in Group Short and found a main effect of session, F (4, 56) = 11.78, MSE = 39.92, p < .001, ηp2 = .46, condition, F (1, 14) = 11.20, MSE = 214.69, p < .01, and an interaction between the two, F (4, 56) = 14.81, MSE = 39.92, p < .001, ηp2 = .51.

Final resurgence test.

R1.

The R1 test data are summarized in both Figure 1 (group means) and Figure 4 (individual subject data). Although resurgence was observed at the end of the experiment in both of the constantly reinforced groups, the effect of alternating R2 extinction sessions was to reduce that effect (see right-hand panel of Fig. 1). A 2 (Duration: Long vs. Short) x 2 (Condition: Constant vs. Alternating) x 2 (Session: Ext 25 to Test) ANOVA assessed R1 responding during the test. This found a main effect of session, F (1, 28) = 28.67, MSE = 1.41, p < .001, ηp2 = .51, a main effect of duration, F (1, 28) = 4.47, MSE = 6.53, p < .05, ηp2 = .14, a main effect of condition, F (1, 28) = 6.69, MSE = 6.53, p < .05, and a session by condition interaction, F (1, 28) = 11.05, MSE = 1.41, p < .01, ηp2 = .28. No interaction involving the duration factor approached significance, largest F = 1.36, p = .25. Pairwise comparisons found that both groups Constant Long, F (1, 28) = 27.92, p < .001, ηp2 = .50, and Constant Short, F (1, 28) = 11.52, p <.01, ηp2 = .29, showed an increase in responding from the last day of extinction to the test. However, neither Group Long Alternating, F (1, 28) = 1.53, p = .23 nor Group Short Alternating, F < 1, did. Further, while Group Long Constant and Group Long Alternating did not differ on the final day of extinction, F (1, 28) = 1.27, p = .27, Group Long Alternating responded significantly less during the test, F (1, 28) = 10.87, p < .01, ηp2 = .28. The same pattern was true of animals that had the short duration Phase 2. While there were no differences during the final day of extinction, F < 1, this difference trended towards significance during the test, F (1, 28) = 3.00, p = .09, ηp2 = .10, with Group Short Alternating responding less than Group Short Constant. Further, while the constant groups did not differ despite their different Phase-2 durations, F < 1, the alternating groups showed a trend in difference based on duration, F (1, 28) = 3.03, p = .09, ηp2 = .10, with the longer duration showing less R1 responding during the test.

R2.

A similar 2 (Duration: Long vs. Short) x 2 (Condition: Constant vs. Alternating) x 2 (Session) ANOVA was conducted on R2 responding during the test (Fig. 2). This found main effects of session, F (1, 28) = 64.26, MSE = 152.73, p < .001, ηp2 = .70, condition, F (1, 28) = 13.17, MSE = 171.95, p = .001, ηp2 = .32, and duration, F (1, 28) = 9.28, MSE = 171.95, p < .01, ηp2 = .25, as well as a marginally significant session by duration interaction, F (1, 28) = 3.32, MSE = 152.73, p = .08, ηp2 = .11. No other main effects or interactions were significant, largest F = 1.72, p = .20. All groups showed a decrease in responding from the final R2 acquisition session to the test (Group Long Constant: F (1, 28) = 14.08, p = .001, ηp2 = .34; Group Long Alternating: F (1, 28) = 37.04, p < .001, ηp2 = .57; Group Short Constant: F (1, 28) = 8.73, p < .01, ηp2 = .24; Group Short Alternating: F (1, 28) = 10.50, p < .01, ηp2 = .27). In both the long duration, F (1, 28) = 113.01, MSE = 19.00, p < .001, ηp2 = .80, and short duration, F (1, 28) = 16.00, MSE = 19.00, p < .001, ηp2 = .36, the alternating groups showed less responding than the constant groups during the test. These differences were not evident on the final day of acquisition, largest F = 1.00, p = .33. Finally, while the constant groups differed depending on duration, F (1, 28) = 28.25, p < .001, ηp2 = .50, with the Group Long Constant responding more than Group Short Constant, this difference was not evident in the alternating groups, F (1, 28) = 1.73, p = .20.

Discussion

Resurgence was observed in the groups that received constant reinforcement of R2 over either 5 or 25 sessions of Phase 2 treatment. The fact that even 25 sessions of typical Phase 2 treatment did not prevent resurgence is reminiscent of previous results of Winterbauer et al. (2013), who found that resurgence survived 36 Phase 2 sessions in which R2 was reinforced on a fixed ratio (FR) 10 schedule. The present results extend the Winterbauer et al. findings to a Phase 2 procedure that involved extensive RI (as opposed to FR) reinforcement of R2 (cf. Shahan & Craig, 2017, p. 117).

The results of Experiment 1 also clearly demonstrate that alternating experience with R2 extinction during Phase 2 reduced the final resurgence effect. These results extend and replicate those reported by Schepers and Bouton (2015, Experiment 3). Further, although R1 resurged in early sessions of R2 extinction in Phase 2, the size of that effect diminished systematically as a function of cycles. Both findings are consistent with the context hypothesis of resurgence (e.g., Trask et al., 2015), as described above. However, they are not consistent with predictions made by the RaC model (Shahan & Craig, 2017, p. 116). As stated earlier, RaC predicts that the magnitude of resurgence should be the same over cycles despite repeated exposure to R2 extinction. RaC also predicts that responding in the final resurgence test should be the same for all groups, because recency of R2 reinforcement is paramount in determining the value of the response, and all groups experienced equally recent R2 reinforcement before the final test.

Experiment 2

Experiment 2 was designed to extend the results described earlier by Bouton and Trask (2016, Experiment 2), where noncontingent presentation of the reinforcer used in Phase 2 suppressed resurgence whereas similar presentation of the Phase 1 reinforcer did not. The present experiment instead compared the effects of noncontingent presentation of a reinforcer associated with R1 extinction with a third reinforcer that had not been associated with either acquisition or extinction of R1. In the new design, R1 was first reinforced with O1 (a sweet-fatty pellet). Then, in a second phase, animals were given two different types of sessions in a double-alternating sequence. In one type of session, R1 was extinguished and R2 produced O2 (either a sucrose-or grain-based reinforcer; counterbalanced). In the second type of session, R1 was unavailable (and therefore not extinguished) and R2 produced O3. The procedure gave the rats similar experience with O2 and O3, but only O2 was associated with R1’s extinction. Animals were then tested in each of three conditions. In one, R1 and R2 were available and not reinforced; resurgence was expected here. In a second, both responses were available and not reinforced, but O2 pellets were delivered freely at the rate they had been earned in Phase 2. In the third condition, O3 reinforcers were instead delivered freely. If the R2 outcome associated with R1’s extinction suppresses resurgence as the context hypothesis suggests, O2 (but not O3) reinforcers would reduce R1 responding relative to the no-reinforcer control condition as they were part of the context in which R1 was extinguished. This would be true even though O2 and O3 are equally familiar and equally associated with R2. However, as noted in the Introduction, RaC assumes that noncontingent presentations of either O2 or O3 could be “misallocated” to R2 during testing; through this process, and because the model has no mechanism to predict different effects of different reinforcers, it implies that free delivery of either O2 or O3 could reduce the decrease in R2’s value during extinction testing (see Shahan & Craig, 2017, p. 121). Thus, if anything, O2 and O3 should equally reduce the resurgence of R1.

Method

Subjects.

The subjects were 24 naïve female Wistar rats purchased from Charles River Laboratories (St. Constance, Quebec), housed and maintained as in Experiment 1. As before, all sessions were 30 min unless otherwise indicated.

Apparatus.

Conditioning proceeded in two sets of four standard conditioning boxes (ENV-008-VP: Med-Associates, St. Albans, VT) that were housed in different rooms of the laboratory. The sets had been modified for use as separate contexts, although they were not used in that capacity here. Boxes from both sets measured 30.5 cm × 24.1 × 21.0 cm (l × w × h), and were the same as the ones used by Bouton and Trask (2016); the boxes are described in full detail there. Levers were positioned to the left and right of the centered food magazine. O1 reinforcers were 45-mg 38% KCal Omnitreat Sweet Fat Tablets (5C2R 1812013). O2 and O3 reinforcers were counterbalanced as either 45-mg MLab Rodent Tablets (also used in Experiment 1) or 45-mg Sucrose Tablets (5TUT 1811251; TestDiet, Richmond, IN). The grain-and sucrose-based pellets have often been used as discriminably different reinforcers in our laboratory (e.g., Bouton, Todd, León, Miles, & Epstein, 2013; Trask & Bouton, 2016; Winterbauer et al., 2013) and were the reinforcers used as O1 and O2 (counterbalanced) by Bouton and Trask (2016, Experiment 2).

Procedure.

Magazine training.

All animals received magazine training on the 2 days prior to the beginning of Phase 1. Both levers were retracted during the sessions. In each, approximately 60 food pellets were delivered to the magazine on a random time 30-s (RT 30-s) schedule of reinforcement. On the first day, all rats received two 30-min sessions, one with O2 (grain-based or sucrose-based pellet, counterbalanced) and one with O3 (sucrose-or grain-based pellet). On the next day, all animals received one 30-min session with O1 (the sweet-fat pellet for all).

R1 acquisition (Phase 1).

All animals then received 12 sessions of instrumental training (2 per day) over the course of the next 6 days. All sessions were initiated by the insertion of their R1 lever (left or right for half the animals). Presses on this lever delivered O1 on a RI 30-s schedule. No additional response shaping was necessary. The two daily sessions were separated by approximately 1.5 hr.

R1 extinction and R2 acquisition (Phase 2).

Over the next 4 days, all animals then received eight 30-min sessions in which R1 presses were extinguished and presses to the newly-inserted second lever (R2) were reinforced with O2 on a RI 30-s schedule. These sessions were double-alternated with eight additional 30-min sessions in which only R2 was available and produced O3 (RI 30-s); R1 was not available or extinguished in the latter sessions. Half the animals received the sessions in the repeating order of O2, O3, O3, O2, and half received them in the order of O3, O2, O2, O3. There was a total of four sessions each day, separated by approximately 1.5 hr.

Resurgence test (Phase 3).

On the day following the conclusion of Phase 2, all rats received three 5-min test sessions (sequence counterbalanced) in which both levers were inserted but neither was reinforced. In one session, no reinforcers were delivered. In a second session, O2 reinforcers were delivered noncontingent on responding on an RT 30-s schedule. In a third session, O3 reinforcers were delivered on an RT 30-s schedule, again not contingent on responding.

Data analysis.

Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used to assess response rates throughout the experiment. α was set to .05. Partial eta squared was again calculated as a measure of effect size. One subject was excluded due to being an outlier on both final R2 sessions during Phase 2 (Field, 2005; Z = 2.58 during the O2 session; Z = 2.35 during the O3 session), which was reflected in outlier performance of R2 during both the None Test (Z = 2.08) and the O3 Test (Z = 2.03).

Results

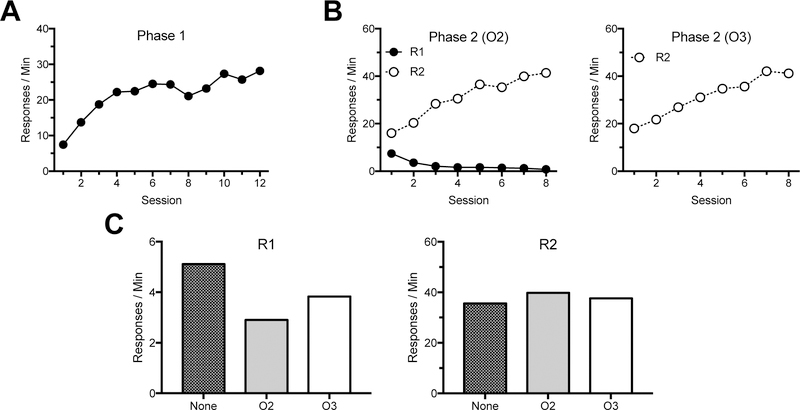

The results from Experiment 2 are summarized in Figure 5. During the crucial test (Panel C), presentation of O2, but not O3, reduced resurgence of R1 responding relative to a no reinforcer control condition.

Fig. 5.

Results of Experiment 2 (mean responses per minute for all rats). Mean R1 acquisition throughout Phase 1 is shown in Panel A. Mean R1 and R2 responding during the two types of Phase-2 sessions are shown in Panel B. During O2 sessions, R1 was extinguished while R2 produced O2. During O3 sessions, R2 produced O3. Mean responding during the final test is shown separately for R1 and R2 in Panel C. None = no noncontingent reinforcers; O2 = noncontingent O2; O3 = noncontingent O3.

R1 acquisition.

Animals increased their responding throughout acquisition (Fig. 5, Panel A). This was confirmed by a within-subject ANOVA conducted to assess responding throughout the 12 acquisition sessions, which found a main effect of session F (11, 242) = 40.92, MSE = 19.58, p < .001, ηp2 = .65.

R1 extinction and R2 acquisition

Across Phase 2 (Fig. 5, Panel B), animals decreased R1 responding, as confirmed by an ANOVA assessing R1 responding over the eight sessions in which it was extinguished. This found a main effect of session, F (7, 154) = 45.67, MSE = 2.37, p < .001, ηp2 = .68. Animals also increased their responding on R2 throughout Phase 2 during both sessions where R2 produced O2 and R2 produced O3. A 2 (Outcome: O2 vs. O3) x 8 (Session) ANOVA was conducted to assess R2 responding throughout Phase 2. This found a main effect of session, F (7, 147) = 18.57, MSE = 187.17, p < .001, ηp2 = .47. No other main effects or interactions were significant, Fs < 1.

Test.

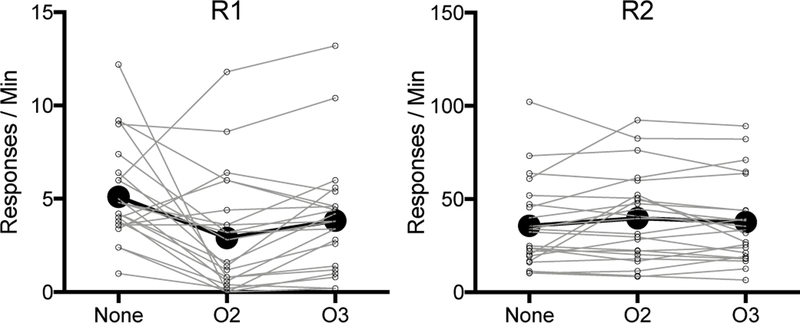

Results of the test sessions are summarized in Panel C of Figure 5 (means) and in Figure 6 (individual subject data). R1 resurged in the control (no reinforcer) test condition in that responding increased relative to the mean responding on the final day of extinction, t (22) = 7.82, p < .001 (see also further analyses reported in the next paragraph). However, as the figures imply, the effect of O2 deliveries during testing was to reduce the amount of R1 responding. A 2 (Response: R1 vs. R2) x 3 (Session: None vs. O2 vs. O3) ANOVA assessed responding during the test. This found a main effect of response, F (1, 22) = 52.01, MSE = 753.73, p < .001, ηp2 = .70, with R2 being higher, and a significant session by response interaction, F (2, 44) = 3.42, MSE = 34.77, p < .05, ηp2 = .13. The main effect of session was not significant, F < 1. Planned comparisons found that R1 responding was less in the O2 test than in the None test (p = .008). Further, there was also significantly less responding in the O2 test relative to the O3 test (p = .004). R1 responding did not differ between the O3 and None tests (p = .10). R2 responding did not differ between any tests (smallest p = .14).

Fig. 6.

Individual subject data during the test of Experiment 2. Bold points and lines represent means.

Because the experiment used a Phase 2 procedure in which R1 was extinguished in two 30-min sessions every day, spontaneous recovery could have potentially enhanced performance on the first session of each day, i.e., the odd-numbered R1 extinction sessions. Therefore, the best indication of resurgence during testing would arguably be an increase in responding from the first 5 min of extinction session 7 (the final first daily session of extinction) to the 5-min control (None) test; conservatively speaking, since the control test was the first daily test for only one-third of the animals, these periods could be equally affected by any spontaneous recovery from the preceding day. Nonetheless, a significant increase in responding was seen between the first 5 min of session 7 to the 5 min of the None test in which no reinforcers were delivered, t (22) = 3.79, p = .001. This result argues strongly against an exclusive role for spontaneous recovery. It is worth noting that we had deliberately conducted extinction beyond the point at which spontaneous recovery was evident during the first daily session. For example, when we compared R1 responding during the first 5 min of session 6 with the first 5 min of session 7 on the next day, there was no difference in responding, t (22) = 0.18, p = .86. All of these observations suggest that the relatively high R1 responding during the None test of the final test day was due to resurgence and not spontaneous recovery.

Discussion

The results of Experiment 2 demonstrate that O2, but not O3, reinforcers delivered freely during the test attenuated the resurgence effect when compared to a no-reinforcer (resurgence) control condition. This result strongly suggests that a reinforcer must be associated with R1’s extinction in order to suppress resurgence when it is presented during resurgence testing. Such a result is not anticipated by the RaC model, because it has no mechanism to distinguish the effects of presenting O2 and O3 during testing. Instead, as described earlier, the two reinforcers should have equally suppressed the value of R1 by maintaining the value of R2 and thus prevented resurgence. It is worth noting that several features of the current procedure (e.g., its use of multiple extinction sessions a day, multiple types of extinction sessions, and shorter within-subject test sessions) could make it difficult to simulate in RaC; in its present form, the model is restricted to predicting response rates during sessions that are equal in duration and equally spaced in time. However, the model does not include a mechanism that can accommodate the role of the discriminative properties of the reinforcer, which is clearly suggested here.

The present findings are in line with those of Bouton and Trask (2016), who found that a reinforcer associated with R1’s extinction suppressed resurgence performance compared to a reinforcer that had been associated with R1’s acquisition. The new contribution of the present experiment is that a reinforcer that was specifically associated with R1 extinction (O2) was more effective at suppressing R1 resurgence than a control reinforcer (O3) that was equally familiar and encountered equally recently. Although the results are consistent with the emphasis on the discriminative influence of reinforcers in the context hypothesis, they continue to challenge the RaC model (Shahan & Craig, 2017).

General Discussion

The results of these experiments extend and refine data reported by both Schepers and Bouton (2015, Experiment 3) and Bouton and Trask (2016, Experiment 2). In Experiment 1, alternating sessions of reinforcement and nonreinforcement of R2 during Phase 2 reduced the final resurgence effect. Further, the magnitude of the resurgence effect systematically declined over Phase 2 in the alternating groups. These results extend and replicate those reported by Bouton and Schepers (2015, Experiment 3). In Experiment 2, a reinforcer that was associated with R1’s extinction reduced resurgence, whereas a second reinforcer that was equally associated with R2, but not with R1’s extinction, did not. These results, like those reported by Bouton and Trask (2016, Experiment 2), suggest that a reinforcer associated with extinction of R1 has the unique ability to reduce resurgence. Experiment 2’s result is consistent with many other results suggesting that reinforcers can have discriminative, as well as reinforcing, properties (e.g., Bouton et al., 1993; Delamater, LoLordo, & Sosa, 2003; Ostlund & Balleine, 2007; Reid, 1958; Rescorla & Skucy, 1969; Trask & Bouton, 2016). Overall, the present results add to a growing literature suggesting that treatments that increase generalization from treatment to testing reduce the resurgence of an extinguished operant response (Bouton & Schepers, 2014; Bouton & Trask, 2016; Schepers & Bouton, 2015; Winterbauer & Bouton, 2012).

The results are consistent with the context hypothesis of resurgence (e.g., Trask et al., 2015; Winterbauer & Bouton, 2010). According to that view, resurgence is a special case of the ABC renewal effect in which reinforcement for R1 creates Context A, reinforcement for R2 creates Context B, and the nonreinforcement conditions during the testing create a new context, Context C. Thus, removal of the extinction context causes a relapse of an extinguished operant response. The explanation suggests that factors that increase the generalization from extinction to testing will be a key factor in reducing resurgence. In the current Experiment 1, alternating sessions in which animals experienced conditions identical to those of resurgence testing (i.e., extinction of both R1 and R2) reduced resurgence, likely because the R1 inhibition learned during that phase generalized to the testing conditions. In Experiment 2, only a reinforcer associated with the inhibition of R1 (i.e., O2) could attenuate resurgence. A similar reinforcer (i.e., O3) with an equal connection to R2 could not because it had not been a part of sessions in which R1 had been extinguished (inhibited).

In contrast, the results pose a challenge to RaC. As previously noted, that model explicitly predicts that, regardless of experience with periods of nonreinforcement during Phase 2, will not have an effect on the magnitude of resurgence (e.g., Shahan & Craig, 2017, Figs. 16 and 17). Contrary to that prediction, Experiment 1 demonstrated that the magnitude of the resurgence effect observed during nonreinforcement sessions decreased systematically as a function of reinforcement-to-extinction cycles, and that the treatment also reduced resurgence relative to animals who receive constant reinforcement across the same number of sessions. In Experiment 2, RaC predicts that both O2 and O3 reinforcers should maintain the value of R2 from the final session of Phase 2 and allow no corresponding (relative) increase in the value of R1. They should thus be equally effective at reducing resurgence. However, only the O2 reinforcer significantly reduced R1 responding; O3 presentations produced significantly less suppression of R1 than did presentations of O2.

It may be worth mentioning another result not anticipated by the RaC model. The model does not presently predict the finding that reverse thinning procedures weaken resurgence relative to a constantly reinforced control (Bouton & Schepers, 2014; Schepers & Bouton, 2015; see Fig. 15 in Shahan & Craig, 2017). In a reverse thinning procedure, R2 receives lean schedules of reinforcement during early (but not late) sessions of Phase 2. The model does not account for the result because the control and reverse-thinned groups receive equivalent rates of reinforcement for R2 soon before the resurgence test.

Finally, the present experiments might have implications for treatments in which problem behaviors are no longer reinforced and are replaced by adaptive behaviors. In one example of this, functional communication training (FCT), children are no longer reinforced for problem behaviors such as acting out or throwing tantrums and are instead rewarded for engaging in prosocial behaviors, such as asking for help (Carr & Durand, 1985). However, consistent with the resurgence effect, problem behaviors can return when reinforcement for the prosocial behavior is discontinued (Sprague & Horner, 1992; Volkert, Lerman, Call, & Trosclair-Lasserre, 2009; see Podlesnik, Kelly, Jimenez-Gomez, & Bouton, 2017). Results from Experiment 1 suggest that experience with periods of nonreinforcement during FCT treatment might reduce later resurgence of problem behavior. Results from Experiment 2 suggest that maintaining specific reinforcers associated with response elimination during FCT will also function to reduce resurgence. According to the context view, both treatments will work because they encourage the generalization of response inhibition learned during treatment to the final resurgence test.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIDA grant R01 DA 033123 to MEB. We thank Catalina Rey, Michael Steinfeld, and Eric Thrailkill for their comments.

References

- Bouton ME, Rosengard C, Achenbach GG, Peck CA, & Brooks DC (1993). Effects of contextual conditioning and unconditional stimulus presentation on performance in appetitive conditioning. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 41B, 63–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, & Schepers ST (2014). Resurgence of instrumental behavior after an abstinence contingency. Learning & Behavior, 42, 131–143. 10.3758/s13420-013-0130-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Todd TP, León SP, Miles OW, & Epstein LH (2013). Within-and between-session variety effects in a food-seeking habituation paradigm. Appetite, 66, 10–19. 10.1016/j.appet.2013.01.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, & Trask S (2016). Role of the discriminative properties of the reinforcer in resurgence. Learning & Behavior, 44, 137–150. 10.3758/s13420-015-0197-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cançado CR, & Lattal KA (2011). Resurgence of temporal patterns of responding. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 95, 271–287. 10.1901/jeab.2011.95-271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr EG, & Durand VM (1985). Reducing behavior problems through functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 18, 111–126. 10.1901/jaba.1985.18-111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delamater AR, LoLordo VM, & Sosa W (2003). Outcome-specific conditioned inhibition in Pavlovian backward conditioning. Learning & Behavior, 31, 393–402. 10.3758/BF03196000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field A (2005). Discovering statistics using SPSS Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Herrnstein RJ (1961). Relative and absolute strength of response as a function of frequency of reinforcement. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 4, 267–272. 10.1901/jeab.1961.4-267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitenberg H, Rawson RA, & Bath K (1970). Reinforcement of competing behavior during extinction. Science, 169, 301–303. 10.1126/science.169.3942.301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitenberg H, Rawson RA, & Mulick JA (1975). Extinction and reinforcement of alternative behavior. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 88, 640–652. 10.1037/h0076418 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ostlund SB, & Balleine BW (2007). Selective reinstatement of instrumental performance depends on the discriminative stimulus properties of the mediating outcome. Learning & Behavior, 35, 43–52. 10.3758/BF03196073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podlesnik CA, Jimenez-Gomez C, & Shahan TA (2006). Resurgence of alcohol seeking produced by discontinuing non-drug reinforcement as an animal model of drug relapse. Behavioural Pharmacology, 17, 369–374. 10.1097/01.fbp.0000224385.09486.ba [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podlesnik CA, Kelley ME, Jimenez-Gomez C, & Bouton ME (2017). Renewed behavior caused by context change and its implications for treatment maintenance: A review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 50, 675–697. 10.1002/jaba.400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quick SL, Pyszczynski AD, Colston KA, & Shahan TA (2011). Loss of alternative non-drug reinforcement induces relapse of cocaine-seeking in rats: role of dopamine D(1) receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology, 36, 1015–1020. 10.1038/npp.2010.239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed P, & Morgan TA (2006). Resurgence of response sequences during extinction in rats shows a primacy effect. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 86, 307–315. 10.1901/jeab.2006.20-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid RL (1958). The role of the reinforcer as a stimulus. British Journal of Psychology, 49, 202–209. 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1958.tb00658.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA, & Skucy JC (1969). Effect of response-independent reinforcers during extinction. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 67, 381–389. 10.1037/h0026793 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schepers ST, & Bouton ME (2015). Effects of reinforcer distribution during response elimination on resurgence of an instrumental behavior. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Learning and Cognition, 41, 179–192. 10.1037/xan0000061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahan TA, & Craig AR (2017). Resurgence as choice. Behavioural Processes, 141, 100–127. 10.1016/j.beproc.2016.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague JR, & Horner RH (1992). Covariation within functional response classes: Implications for treatment of severe problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 25, 735–745. 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney MM, & Shahan TA (2013a). Effects of high, low, and thinning rates of alternative reinforcement on response elimination and resurgence. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 100, 102–116. 10.1002/jeab.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney MM, & Shahan TA (2013b). Behavioral momentum and resurgence: Effects of time in extinction and repeated resurgence tests. Learning & Behavior, 41(4), 414–424. 10.3758/s13420-013-0116-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trask S, & Bouton ME (2016). Discriminative properties of the reinforcer can be used to attenuate the renewal of extinguished operant behavior. Learning & Behavior, 44, 151–161. 10.3758/s13420-015-0195-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trask S, Schepers ST, & Bouton ME (2015). Context change explains resurgence after the extinction of operant behavior. Mexican Journal of Behavior Analysis, 41, 187–210. 10.5514/rmac.v41.i2.63772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkert VM, Lerman DC, Call NA, & Trosclair-Lasserre N (2009). An evaluation of resurgence during treatment with functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 42, 145–160. 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterbauer NE, & Bouton ME (2010). Mechanisms of resurgence of an extinguished instrumental behavior. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes, 36, 343–353. 10.1037/a0017365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterbauer NE, & Bouton ME (2012). Effects of thinning the rate at which the alternative behavior is reinforced on resurgence of an extinguished instrumental response. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes, 38, 279–291. 10.1037/a0028853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterbauer NE, Lucke S, & Bouton ME (2013). Some factors modulating the strength of resurgence after extinction of an instrumental behavior. Learning and Motivation, 44, 60–71. 10.1016/j.lmot.2012.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]