Abstract

Introduction:

The octapeptins are a family of cyclic lipopeptides first reported in the 1970s then largely ignored. At the time, their reported antibiotic activity against polymyxin-resistant bacteria was a curiosity. Today the advent of widespread drug resistance in Gram-negative bacteria has prompted their ‘rediscovery’. The paucity of new antibiotics in the clinical pipeline is coupled with a global spread of increasing antibiotic resistance, particularly to meropenem and polymyxins B and E (colistin).

Areas covered:

We review the original discovery of octapeptins, their recent first chemical syntheses, and their mode of action, then discuss their potential as a new class of antibiotics to treat extensively drug resistant (XDR) Gram-negative infections, with direct comparisons to the closely related polymyxins.

Expert Commentary:

Cyclic lipopeptides in clinical use (polymyxin antibiotics) have significant dose-limiting nephrotoxicity inherent to their chemotype. This toxicity has prevented improved polymyxin analogs from progressing to the clinic, and tainted the perception of lipopeptide antibiotics in general. We argue that the octapeptins are fundamentally different from the polymyxins, with a disparate mode of action, spectra of action against MDR and XDR bacteria and a superior pre-clinical safety profile. They represent early stage candidates that can help prime the antibiotic discovery pipeline.

Keywords: Antibiotics, antimicrobial resistance, bacterial infection, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), colistin, extensively drug-resistant (XDR) bacteria, Gram-negative bacteria, lipid A, lipopeptide, multi-drug-resistant (MDR) bacteria, octapeptin, polymyxin, polymyxin resistance

1. Introduction

1.1. Antimicrobial Resistance

Antimicrobial resistance is a growing global concern, with predictions that the rise of drug-resistant bacteria will contribute to 10 million deaths annually by 2050 if left unchecked.[1] Infections by resistant Gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, are particularly concerning[2] as it is more difficult to develop new antibiotics against this type of bacteria compared to Gram-positive bacteria, due to their additional outer membrane (preventing antibiotic entry) and efficient efflux pump systems (exporting any antibiotics that penetrate the membrane). Carbapenem antibiotics, effective against resistant bacteria such as extended spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae, are under threat due to the rise of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE). [3–8] CRE produce β-lactamase carbapenemases such as KPC (K. pneumoniae carabapenemase), NDM-1 (New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-1) and OXA-48 (oxacillinases)[9], which inactivate the antibiotic by hydrolysing the active β-lactam warhead. These enzymes are frequently encoded on plasmids, mobile genetic elements that allow for rapid dissemination.[10] While most ‘superbugs’ are more prevalent in a hospital setting, the NDM-1 gene is now reported in community-acquired infections with E. coli, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii.[11] The latter three are of particular concern for critically ill patients where ventilator associated pneumonia is common, and P. aeruginosa is a major cause of infection in patients with cystic fibrosis. CRE infections tend to be associated with co-infection with other pathogens, time delays for effective therapy, and patients with multiple morbidities; isolation of CRE from any site is associated with all-cause hospital mortality ranging from 29–52%.[7] Very few antibiotics retain activity against CRE, including polymyxins (polymyxin B and polymyxin E = colistin), some aminoglycosides, fosfomycin, and tigecycline, which have become the “drugs of last resort”.[7] [12] A number of new antibiotics, either recently approved (Avycaz, the β-lactamase inhibitor avibactam in combination with the cephalosporin ceftazidime; VABOMERE, the β-lactamase inhibitor vaborbactam in combination with the carbapenem meropenem) or in late stage clinical development (such as the aminoglycoside plazomicin by Achaogen, the tetracycline eravacycline by Tetraphase, the monobactam LYS-228 by Novartis, and the combination of avibactam with the monobactam, aztreonam by AstraZeneca) are also able to treat CRE infections. However given the history of evolution of resistance against all antibiotics, more candidates are needed in the pipeline.

The emergence of these multidrug-resistant (MDR), extensively drug-resistant (XDR) and pan-drug resistant E. coli, A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa and K. pneumoniae nosocomial infections has led to resurgence in the use of the ‘last resort’ polymyin antibiotics polymyxin E (colistin).[13–15] Unfortunately, colistin therapy is already compromised by the increasing prevalence of colistin-resistant strains,[16–18] partly driven by suboptimal dosing regimens[19] and dose-limiting toxicity that leads to treatment failure and the promotion of polymyxin-resistance (Pmx-R).[20] Colistin was widely used as a livestock food additive in China (8000 tonnes out of global production of 12,000 tonnes per year), but in November 2016 China banned its use, as has Brazil, rendering India now the largest user of this ‘last resort’ clinical antibiotic in animals.[21] Pmx-R MDR and XDR strains are becoming virtually untreatable with increased morbidity, mortality and associated healthcare costs. The recent emergence of plasmid-borne Pmx-R encoded by the mcr-1 gene supports the argument that resistance to these last resort treatment options can now rapidly spread under selection pressure; the gene itself has actually been present in bacteria for many years.[1, 22–24] A similar situation is on the horizon in many regions of the world for Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections where currently ceftriaxone is the only reliable treatment option left and the emergence of a ceftriaxone-resistant strain of N. gonorrhoeae could lead to a sexually transmitted global epidemic.[25–27] Currently, in most countries, extended-spectrum cephalosporins (ESCs) are the only single antibiotic that remain effective for treating gonorrhoea. But resistance to cefixime – and more rarely to ceftriaxone – has now been reported in more than 50 countries. As a result, WHO issued updated global treatment recommendations in 2016 advising doctors to give 2 antibiotics: ceftriaxone and azithromycin.[28]

There is a clear and urgent medical need for new antibiotics to treat infections caused by MDR and XDR Gram-ve pathogens, but, there are very few antibiotic drug candidates in the pharmaceutical pipeline.[29–33] Without resource allocation to the discovery and development of effective antibiotics now, we face a very real threat that pandemic, virulent XDR bacterial strains could kill millions in the not-so-distant future.

1.2. Polymyxin Antibiotics

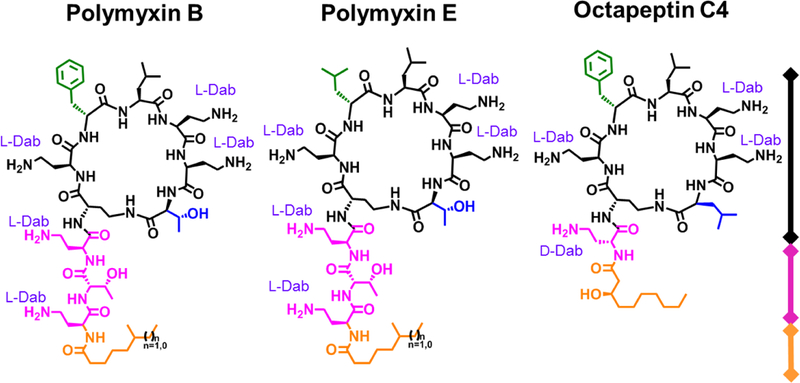

The polymyxin antibiotics are lipopeptides consisting of a cyclic heptapeptide core with an N-terminal tripeptide tail capped with a lipophilic fatty acid (see Figure 1). The peptides are highly basic with a net +5 charge, containing six unusual 2,4-diaminobutyric acid residues, one of which is used to form the cyclic ring via amidation of the side chain amine with the C-terminal acid group. They were independently discovered in 1947 by three research groups, with two American groups isolating them from Bacillus polymyxa.[34–36] and a British group reporting ‘aerosporin’ isolated from B. aerosporus, which was subsequently confirmed to also be B. polymyxa.[37] Colistin was also reported in 1950 by a Japanese group.[38] Eleven distinct types of polymyxins have been isolated from nature ( A, B, C, D, E, F, K, M, P, S, and T), with some families containing multiple subtypes.[39–44] Because the polymyxins are produced by fermentation, their composition and purity varies between manufacturers.[45] A large number of the components have recently been chemically synthesised and compared for in vitro and in vivo efficacy and toxicity; with polymyxin S2 potentially showing a better profile than B and E.[46]

Figure 1.

Structures of Polymyxin B, Polymyxin E (colistin) & Octapeptin C4 (OctC4)

The two polymyxins that have entered clinical use are Polymyxin B (as polymyxin B sulfate) and Polymyxin E (colistin), differing only by a D-Phe/D-Leu alteration at position-6. Both are mixtures containing predominantly two components that vary in the fatty acid tail, with (S)-6-methyl-octanoic acid in polymyxin B1/E1 or 6-methyl-heptanoic acid in polymyxin B2/E2. However, up to 39 possible components have been identified for polymyxin B,[47] and 36 for polymyxin E.[48] While polymyxin B is used clinically as the sulfate salt, colistin is generally (but not always) administered as a prodrug (colistimethate sodium), an even more poorly defined mix of derivatives where the free amines of the Dab residues have been masked by polymethanesulfonylation. The prodrug spontaneously hydrolyzes to form colistin A (polymyxin E1) and B (polymyxin E2/B) after administration, with the masked Dab groups designed to reduce nephrotoxicity associated with initial peak levels following intravenous administration.

A 1949 review on the initial human clinical use of the polymyxin antibiotics presciently concluded that there is “little doubt that polymyxins have exhibited effective therapeutic activity in certain infections of man produced by Gram-negative bacteria. It is apparent, however that their application in this field is likely to be limited because of the occurrence of untoward reactions elicited by material used in the clinical trials.”[49] Indeed, one of the main limitations that prevented significant use of the polymyxins in the 1970s-90s was nephrotoxicity, with adverse renal toxicity observed in over 50% of cases in some studies; neurotoxicity is also a concern.[50–54] However, as discussed earlier, in recent years the polymyxins have become last-resort antibiotics for MDRGram-negative infections, creating significant interest in their use [55–60] and in turn, a concerted effort to understand and improve dosing to alleviate toxicity and enhance efficacy.[19, 61–65]. The reasons why the polymyxins cause nephrotoxicity are not well understood at a mechanistic level, though they are cytotoxic to renal tubular cells and accumulate in these cells because of non-passive renal handling mechanisms.[53, 66, 67] The total daily dose and longer duration of therapy are associated with increased toxicity, which is usually reversed after treatment is stopped.[53, 68–71] Polymyxin B is increasingly recognized as causing reduced acute kidney injury compared to colistimethate.[72] The antioxidants melatonin[73] and ascorbic acid[74] were both found to show a protective effect against colistin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats, with melatonin also altering colistin pharmacokinetics by reducing clearance rates. The neurotoxicity effects of the polymyxins are less common, reported in approximately 4–7% of patients as paresthesias (tingling or ‘pins and needles’) and polyneuropathy (weakness, numbness, and burning pain) due to damage to peripheral nerves.[54, 75, 76]

1.3. Polymyxin Analogs

Attempts have been made to improve the polymyxins by several research groups, with early efforts at polymyxin structure-activity relationship studies summarized by Storm et al. in 1977,[77] and more recent developments reviewed by Velkov et al. in 2010 [78] and 2016,[79] Vaara in 2013,[80] 2016 (with others)[81] and 2018,[82] Kadar et al. in 2013,[56] and Brown and Dawson [83] and Rabanal and Cajal [84] in 2017. A more general review of lipopeptides isolated from Bacillus and Paenibacillus spp. including the polymyxins, octapeptins, polypeptins, iturins, surfactins, fengycins, fusaricidins, and tridecaptins, as well as some novel examples such as the kurstakins, was published by Cocharane and Vederas in 2016.[85] Additional studies preparing new polymyxin analogs were reported by the groups of Rabanal et al. in 2015 (disulfide-cyclized versions)[86] and Gallardo-Godoy et al. in 2016 (a structure-activity relationship study varying all positions).[87] These studies are generally focused on improving activity while reducing nephrotoxicity, as measured by in vitro (and sometime in vivo) assays.[83]

More advanced analogs have included a Phase 1 clinical candidate developed by Cubist, CB-182 804, polymyxin B with the fatty acid acyl group replaced by a urea linked 2-chlorophenyl group. In vitro MIC values and in vivo efficacy was similar to polymyxin B, but the EC50 against a rat renal proximal tubule cell line was >1000 μg/mL compared with 318 μg/mL for polymyxin B,[83] and in vivo nephrotoxicity in Cynomolgus monkey was clean at doses up to 3.2 mg/kg bid, although the same dose tid resulted in significant lesions similar to those induced by 3.8 mg/kg polymyxin B bid.[88, 89] The compound was withdrawn from clinical trials in 2011, apparently due to nephrotoxicity. Pfizer developed a polymyxin B derivative (named 5x) with the fatty acid replaced by a 6-oxo-1-phenyl-1,6-dihydropyridine-3-carbonyl moiety and Dab-3 by Dap-3.[90] The analog showed reduced toxicity in in vitro testing against an hRPTEC cell line, with EC50 >100 μM vs polymyxin B = 22 μM. Histopathology showed no lesion in rats dosed at 8 mg/kg for 7 days, a dose at which polymyxin B was not tolerated, but in dogs similar levels of lesions were observed, although with a 1.8-fold higher dose of compound 5x.[90]

Issues related to nephrotoxicity for all polymyxin programs are nicely summarized in the recent polymyxin reviews of Rabanal and Cajal [84] and Vaara’s 2018 review.[82]

1.4. Polymyxin Mode of Action

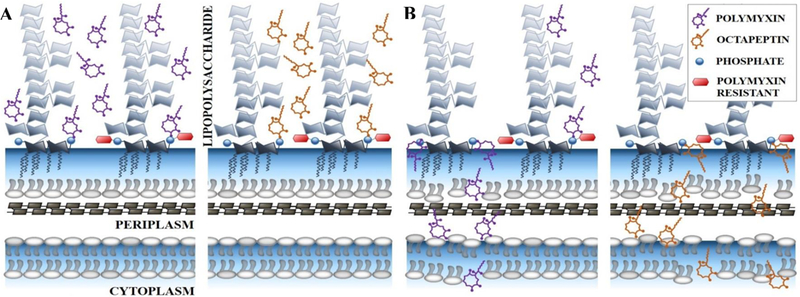

The polymyxins act primarily via disruption of the integrity of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, and it is well-established that this proceeds by initially binding to lipid A, a component of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) that anchored on the outer membrane of G-ve bacteria and essential for bacterial viability (see Figure 4). Numerous biophysical techniques (ITC, NMR, SPR) have been used to characterize the interaction of Pmx with bacterial membranes.[91], The multiple positive charges from the diaminobutyric acid (Dab) side chains on the polar face of the amphipathic polymyxin interact with the anionic polar phosphate head group of lipid A, displacing Mg2+ and Ca2+ divalent cations that bridge the lipid A phosphoesters. This displacement destabilizes the outer membrane and facilitates insertion of the lipophilic face of polymyxin into the membrane, resulting in disruption of the packing of the hydrophobic acyl chains of lipid A. Polymyxin then inserts into the inner membrane, leading to cell lysis and death. Additional mechanisms have been postulated above and beyond the membrane disruption, such as binding to ribosomal RNA[92] and inhibition of NADH-quinone oxidoreductase activity,[57] but it is not clear how significant these other properties are at contributing to the overall killing activity.

Figure 4.

Proposed mode of action for polymyxins and octapeptins in Gram-negative bacteria, showing activity against polymyxin-sensitive (left structure within each pair) and polymyxin-resistant (right structure within each pair) lipid A.

(A) Initial electrostatic attraction between antibiotics and basal component of lipopolysaccharide, lipid A. Interaction between the negatively charged phosphate groups of lipid A and diaminobutyric acid residues on the antibiotics.

(B) Infiltration of antibiotics results in the permeabilisation of the outer and inner membrane, cytoplasmic leakage and subsequent lysis. This arises for both antibiotics except for polymyxins and polymyxin-resistant lipid A. Polymyxin-resistant lipid A contains the addition of either 4-amino-4-deoxy-arabinose, phosphoethanolamine or galactosamine on one or both phosphate groups.

As discussed earlier, the increased use of the polymyxins has led to a concomitant increase in reports of colistin-resistant strains of E. coli, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii. Resistance primarily arises by modifications to the lipid A target, via attachment of 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose, phosphoethanolamine or galactosamine onto the lipid A phosphate groups. These changes result in reduction of the lipid A negative charge and a lower binding affinity for the positively-charged polymyxins.[23, 93, 94] The resistance generally arises due to mutations in the PmrAB and PhoPQ regulatory systems. Plasmid-transmitted resistance occurs through the mcr-1 gene, which encodes a phosphoethanolamine transferase enzyme to accomplish the headgroup modification.[95] Additional membrane modifications, involving deacylation of lipid A, have been identified in P. aeruginosa.[96]

2. The Octapeptins

2.1. Discovery, Nomenclature, and Initial Biological Activity

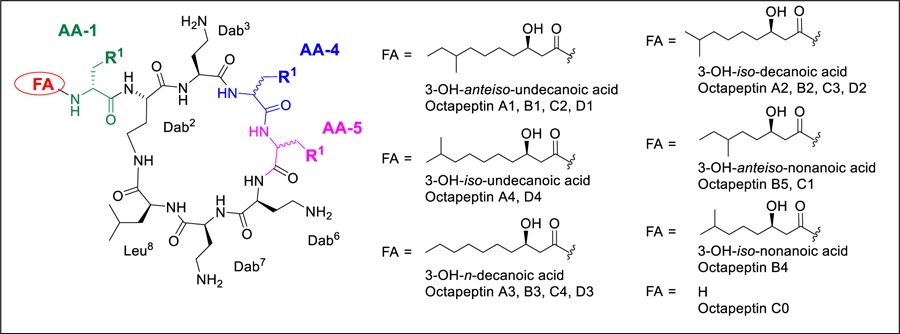

The octapeptin family, structurally similar to the polymyxins, is comprised of 18 closely related cyclic lipopeptides that were isolated from strains of Bacillus circulans[97] and Paenibacillus tianmuensis,[98] with most members identified during the 1970s and early 1980s.[77, 97, 99–104] They contain a cyclic heptapeptide core of nearly identical composition as the polymyxins, but with a C-terminal Leu residue instead of the polymyxin Thr residue. More distinctly, they possess a single exocyclic D-Dab8 (or D-Ser8) residue instead of the L-Dab8-L-Thr9-L-Dab10 tripeptide found in the polymyxins, leading to a reduction in overall positive charge from five to four. This is Nα-capped with various 3-hydroxy fatty acid substituents, rather than the pure alkyl fatty acids found in the polymyxins. The octapeptins are grouped into four subclasses, octapeptins A, B, C, and D, based on their amino acid sequence, with changes found at AA4, AA5, and AA8.[105] The structures of the octapeptins are illustrated in Table 1. Interestingly, the most recently discovered octapeptin B5 (battacin) has a reversed stereochemistry for AA4 and AA5 compared to other members of the same subclass e.g. with D-Phe4–L-Leu5 instead of L-Phe4–D-Leu5.[98] There may be a 19th member of the octapeptin family; BU-1880 was described in a 1975 patent but a definitive structure was never established, with amino acid analysis showing it contains the same amino acid and fatty acid composition as octapeptins B1 and C2.[106]

Table 1.

Octapeptin structures

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Octapeptin | FA | AA1 | AA4 | AA5 |

| A1 | 3-OH-anteiso-undecanoic acid | D-Dab | D-Leu | L-Leu |

| A2 | 3-OH-iso-decanoic acid | |||

| A3 | 3-OH-n-decanoic acid | |||

| A4 | 3-OH-iso-undecanoic acid | |||

| B1 | 3-OH-anteiso-undecanoic acid | D-Dab | D-Leu | L-Phe |

| B2 | 3-OH-iso-decanoic acid | |||

| B3 | 3-OH-n-decanoic acid | |||

| B4 | 3-OH-iso-nonanoic acid | |||

| B5 (batticin) | 3-OH-anteiso-nonanoic acid | D-Dab | L-Leu | D-Phe |

| C0 | H | D-Dab | D-Phe | L-Leu |

| C1 | 3-OH-anteiso-nonanoic acid | |||

| C2 | 3-OH-anteiso-undecanoic acid | |||

| C3 | 3-OH-iso-decanoic acid | |||

| C4 | 3-OH-n-decanoic acid | |||

| D1 | 3-OH-anteiso-undecanoic acid | D-Ser | D-Leu | L-Leu |

| D2 | 3-OH-iso-decanoic acid | |||

| D3 | 3-OH-n-decanoic acid | |||

| D4 | 3-OH-iso-undecanoic acid | |||

The individual members within one subclass vary in the nature of the fatty acid side chain. These N-terminal substituents are all 3-hydroxy fatty acids of varying chain lengths and branch types, though octapeptin C0 completely lacks a fatty acid side chain. The original stereochemical assignment of the substituents in the fatty acid side chain was derived from optical rotation values determined for three side chains in a mixture of octapeptins A1, A2, A3 and/or B1, B2, B3 B3.[103] They were determined to be the (R)-configuration for both the 3-hydroxy and the anteiso methyl group (iso-methyl branched fatty acids have the branch point on the penultimate carbon, one from the end, while anteiso-methyl-branched fatty acids have the branch point on the ante-penultimate carbon atom, two from the end). While subsequent articles refer to this assignment, no independent synthetic verification of the stereochemistry in the fatty acids was performed for other octapeptins.

First isolated and assessed as mixtures from fermentation, the octapeptins were reported to show good activity against Gram-negative bacteria, [97, 102], intriguingly these early reports also described activity against polymyxin-resistant E. coli [97, 101], a property which has led to the current resurgence of interest over 40 years later. Other differences in biological properties compared to the polymyxins were also noted, including weak activity against Gram-positive bacteria, antifungal activity, and no development of resistance during successive subculturing, indicating a lower propensity to induce resistance compared to the polymyxins.[99] The octapept-ns (and polymyxins) possess a superficial resemblance to the Gram-positive antibiotic daptomycin (cyclic peptide core structure, lipid tail - since daptomycin has an acylated tripeptide linear tail it actually more closely resembles the polymyxins. We believe that the Gram-positive activity of the octapeptins is primarily due to general overall lipophilicity, as we have noted in our SAR studies that polymyxin analogs with greater hydrophobicity also pick up Gram positive activity (and cytotoxicity).

In vivo studies of the isolated octapeptins showed efficacy in several mouse models, including when administered subcutaneously against S. pyogenes and E. coli,[99] intramuscularly against E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and P. aeruginosa,[102] intravenously against E. coli[98] and topically for P. aeruginosa.[99] Despite their increased activity against both Gram-positive bacteria and fungi compared to the polymyxins, a property often associated with generally increased toxicity against mammalian cells, initial in vivo toxicity studies in mice indicated moderate trends for reduced toxicity compared to the polymyxins (two- to four-fold). Octapeptin C2 possessed an i.v. LD50 of 35 and s.c. LD50 280 mg/kg, compared to 8.8 and 115 mg/kg for colistin.[102, 104] The more recent report describing octapeptin B5 measured an LD50 of 15.5 mg/kg, compared to 6.5 mg/kg for polymyxin B, with histopathological studies showing no obvious changes in the organs of treated mice.[98] Octapeptin C0, with no lipophilic tail, was less toxic than colistin when dosed intraveneously (LD50 = 35 mg/kg) but more toxic when dosed subcutaneously (LD50 = 56 mg/kg).[102, 104]

Until 2017, only two research articles had been published on the octapeptins, following the initial flurry of research in the 1970–1980’s; the report on battacin’s (octapeptin B5) discovery in 2012,[98] and an article describing its chemical synthesis in 2015.[107] The latter article, and two subsequent publications, examined the potential of octapeptins derived from OctB5 to disrupt and prevent the formation of S. aureus, E. coli and P. aeruginosa biofilms and act as surface coatings,[108] and investigate the antifungal activity of linear analogs.[109] In the last year, four more articles[110–113] have described the first syntheses of other octapeptin family members, initiating a concerted research program to convert them into new antibiotics. Two recent reviews[85, 114] highlight the rapid increase in interest in these compounds and the power of rediscovering compounds from the golden age of antibiotic discovery

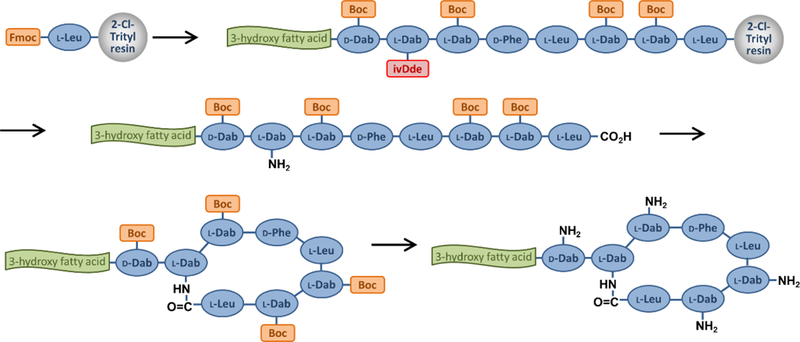

2.2. Synthesis

In comparison to other lipopeptide antibiotic families, such as the polymyxins or daptomycin, until very recently there were no systematic studies that established structure-activity or structure-toxicity relationships for the octapeptins, nor a therapeutic index. Initial reports on synthetic modification of the octapeptins were restricted to a handful of publications that replaced the 3-hydroxy fatty acyl chain with simple, long-chain aliphatic acids[115] or conducted non-selective polyacylation and poly-alkylation of the multiple Dab side chains.[116]. Testing was usually performed on mixtures of compounds, so the quality of even this limited data was poor. The first chemical syntheses of octapeptins were reported in the past few years, with octapeptin B5 in 2015,[107] and both octapeptin C4[111, 112] and octapeptin A3[113] in 2017. A number of octapeptin analogs were also reported in these,[111] [112] and subsequent,[110] articles.

For octapeptin C4 the linear acylated peptide was assembled on a 2-chlorotrityl resin via attachment of the acid group of the C-terminal Leu residue, followed by Fmoc-based solid phase peptide synthesis utilizing Boc side chain protection on 4 of the 5 Dab side chains (see Figure 2). The Dab side chain amine destined to be incorporated within the macrocycle was protected with an ivDde group. Once the fully protected resin-bound peptide with hydrazine was followed by cleavage of the protected peptide from the resin with 20% hexafluoroisopropanol, cyclization using DPPA for activation, then global deprotection with TFA. [111] Octapeptin A3 was prepared following the same procedure,[113] as were a series of analogs for an octapeptin C4 alanine scan.[110] The synthesis of octapeptin B5 (battacin) employed an almost identical strategy, but replaced the ivDde protecting group with a highly acid sensitive Mtt group; 20% 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol removed the Mtt protecting group and cleaving the otherwise protected peptide from the resin.[107]

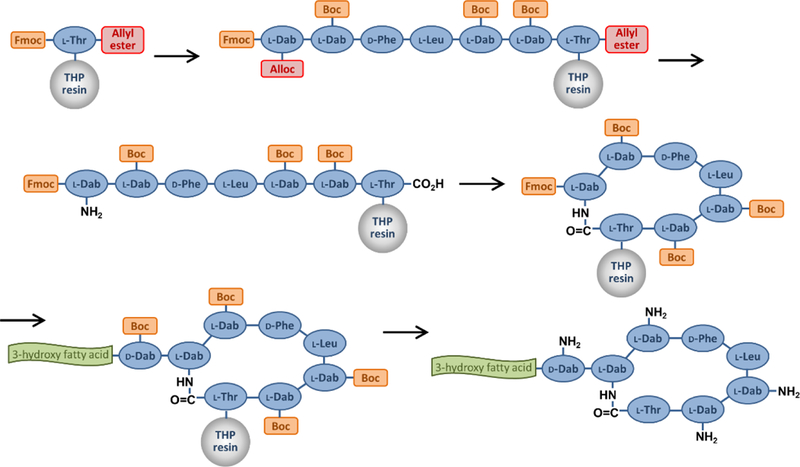

Figure 2.

Off-resin cyclisation synthesis route

An alternative synthesis route was employed for some hybrid analogs containing a polymyxin-like C-terminal Thr residue (see Figure 3). The side chain of Fmoc-Thr allyl ester was attached to a DHP polystyrene resin and the peptide chain assembled by Fmoc SPPS (with Boc side chain protection) until the seventh residue, containing the macrocyle-forming side chain amine with Alloc protection, Fmoc-Dab(Alloc), was added. Pd-catalyzed Alloc/allyl ester deprotection was followed by on-resin cyclisation. Fmoc removal, addition of the terminal D-Dab residue and fatty acid group, and simultaneous global deprotection/resin cleavage completed the synthesis. [112]

Figure 3.

On-resin cyclisation synthesis route

The biosynthetic gene cluster responsible for producing OctC4 was identified and annotated from B. circulans ATCC 31805, showing eight nonribosomal peptide synthesis (NRPS) units (corresponding to the eight amino acid acid residues), with the first and fourth modules containing epimerization domains (correlating with the two D-amino acids). The cluster also codes for an enzyme consistent with that required to convert aspartate β-semialdehyde into Dab residues.[112]

2.3. in vitro Biological Activity

The synthetic octapeptins have activity (MIC values) against the common Gram-negative pathogens E. coli, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii of around 2–8 µg/mL, similar to the initial reports and approximately 8- to 32-fold less potent than the polymyxins (0.25–0.5 µg/mL). OctC4 in particular was found to have relatively poor activity against A. baumannii compared to E. coli, P. aeruginosa and K. pneumoniae, presumably due to variations in the A. baumannii outer membrane.[112] The octapeptins do have moderate activity against the Gram-positive S. aureus (16–32 µg/mL of OctC4 and OctA3). OctC4 was inactive against the fungi Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, Candida parapsilosis, and Aspergillus fumigatus (>100 µg/mL), but quite active against Cryptococcus gattii (3 µg/mL) and several Cryptococcus neoformans strains (1.5–6.2 µg/mL).[110]

The first synthesis of OctB5 in 2015 also prepared 9 analogs, 4 with alternate lipophilic groups (Fmoc, 4-methylhexanoyl, geranyl, myristyl), one replacing all 5 Dab residues with Lys, and 4 corresponding linear analogs.[107] The Fmoc analog had similar activity as OctB5 vs Gram-negative bacteria, but was greater than 10-fold more active against S. aureus (and far more hemolytic against mouse blood), while the shorter chain non-hydroxy 4-methylhexanoyl group had a similar profile to OctB5. The least active derivative contained the geranyl substituent (approximately 10-fold loss in activity); surprisingly the all-Lys analog retained reasonable activity depending on bacterial strain (equipotent to B5 or up to >100-fold less active). Even more surprisingly, the corresponding linear analogs were all more potent (consistently 10-fold) that their cyclic partners; the 4-methylhexanoyl linear derivative had MIC = 1–10 µM (approx. 1–10 µg/mL) for 6 bacterial strains, including S. aureus. An alanine scan of the linear peptide was also reported, substitutions of Leu-4 and Phe-5 with Ala abolished most activity but Dab replacements did not.[107] The linear 4-methylhexanoyl Oct B5 analog was selected for further characterization. It was bactericidal at 20x MIC within 3 h against E. coli and S. aureus, and 9 h vs P. aeruginosa, but bacteriostatic at lower concentrations. It could also inhibit biofilm formation and eradicate existing biofilms of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus between 10–50 µM.[107] A set of 16 linear analogs, mainly varying the fatty acid substituent, were then prepared for testing their antifungal activity against C. albicans planktonic and biofilm cultures.[109]

The 2017 report of synthetic OctC4 also prepared a linear analog, but in this case it lost two- to >16-fold activity.[111] OctC4 itself was subsequently profiled against a wider range of polymyxin-sensitive and polymyxin-resistant strains.[112] While the MICs against sensitive strains (4–16 µg/mL) were reduced compared to PmxB and colistin (0.25–1 µg/mL), against highly resistant clinical isolates (PmxB, colistin = 4->128 µg/mL), OctC4 gained activity (0.5–32 µg/mL) compared to its activity against most sensitive strains. The exception to improved activity of OctC4 compared to PmxB/colistin against resistant strains was against a set of 21 mcr-1 isolates that exhibited only moderate levels of Pmx resistance (2–16 µg/mL, generally 4–8 µg/mL); in this case the OctC4 activity was comparable (2–8 µg/mL).[112] In static time kill assays against a polymyxin-resistant strain of P. aeruginosa, Oct C4 showed a six log10 CFU/mL kill, with no bacterial growth being detected between 0.5 and 6 hr at 32 μg/mL, compared to little killing action from colistin, and rapid regrowth from PmxB at the same concentrations. Regrowth was observed with OctC4 by 24h, with a final overall five log10 CFU/mL reduction, vs three log10 CFU/mL reduction for PmxB. [112]

A limited set of five analogs were prepared to explore the variations between polymyxin and octapeptin activity, with the fatty acid varied between 3-hydroxydecanoic acid, decanoic acid or octanoic acid, and the C-terminal residue alternating between octapeptin’s Leu and polymyxin’s Thr. Activity against both PmxS and PmxR strains was generally retained with the non-hydroxy fatty acid chains, but reverting the Leu to Thr did reduce the octapeptin analog activity against both PmxS and PmxR strains of K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii, though not P. aeruginosa.[112]

2.4. in vivo Biological Activity of Synthetic Octapeptins

In a mouse bacteremia model against susceptible P. aeruginosa (PmxB = 0.5, Oct A3 2 µg/mL), a 4 mg/kg iv dose of Oct A3 was less effective than PmxB (−1.22 log-fold reduction vs −2.55 compared to untreated control after 4h), but against two PmxR strains (PmxB MIC>32 µg/mL, Oct A3 1–2 µg/mL), PmxB was ineffective (−0.37, 0.05) while Oct A3 had similar reductions as with the sensitive strain (−1.11 and −1.38 lo-fold reduction).[113]

A lethal challenge IP infection model of E. coli ATCC 35318 in mice showed 90% survival with 4 mg/kg (50% with 2 mg/kg) of Oct B5; with an MDR clinical isolate 100% survival was seen with 4 mg/kg OctB5 or PmxB, vs 7/8 death with saline.[98]

OctC4 had substantially lowered clearance and increased half-life in mice compared to PmxB (4.1 ml/min/kg vs 7.3 mL/min/kg and 6.6 h vs 3.6 h), but with much higher protein binding (>90% vs 51%).[112] In a mouse neutropenic blood infection model, OctC4 and analogs were approximately 50% less effective than PmxB at reducing the cfu against a sensitive strain of P. aeruginosa, but with PmxR P. aeruginosa, OctC4 analogs (but not OctC4 itself) were substantially better than PmxB. The relative inactivity of OctC4 was postulated to be due to the high plasma protein binding.

2.5. Toxicity / Nephrotoxicity

Acute toxicity in mice was seen with 100% lethality at 25 mg/kg of Oct B5, and an LD50 of 15.5 mg/kg, compared to 6.5 mg/kg Polymyxin B in the same study, with no obvious differences between male and female mice.[98]

For OctC4, subcutaneous dosing of 40 mg/kg in mice showed no acute effects, while PmxB caused decreased respiratory rate and reduced activity.[112] In vitro assessment of LDH or γ-glutamyltransferase release from human proximal kidney tubule cells[117] showed significantly reduced predicted nephrotoxicity compared to PmxB, colistin, and gentamicin. This human cell line-derived data was supported by mice treated with an accumulated OctC4 dose of 72 mg/kg in 24h, compared to PmxB, colistin or saline. Histopathological examination of kidney sections showed no signs of damage in the OctC4-treated mice, but damaged tubules and severe lesions in the PmxB/colistin mice. It remains to be established if the octapeptins have an improved therapeutic index, given that their reduced nephrotoxicity is accompanied by reduced antimicrobial potency.

2.6. Mode of Action

The fact that octapeptins are active against polymyxin-resistant bacteria possessing a wide variety of lipid A modifications suggests that the mode of action may differ between these two classes of antibiotics, despite their structural similarity (see Figure 4). The reduction in positive charge of the octapeptins likely accounts for some differences from the polymyxins.

Early studies on octapeptins reported damage to E. coli outer membranes, accompanied by a release of phospholipids into the assay media that was not seen with polymyxin B.[125] Recent octapeptin analogs have been investigated for their ability to cause membrane damage by a number of methods. Initial studies of battacin against P. aeruginosa loaded with the fluorescent dye diSC3–5 indicated that membrane depolarization, with damage to the cytoplasmic membrane, was responsible for the killing activity.[98] The subsequent report on a more potent linear analog also demonstrated membrane damage, this time using an N-phenylnaphthylamine (NPN) dye(fluoresces when embedded in hydrophobic environment) to indicate concentration-dependent outer membrane damage in P. aeruginosa, and a propidium iodide fluorescent assay (fluoresces when bound to DNA) to show disruption of both P. aeruginosa and S. aureus.[107] Scanning electron microscopy confirmed perturbed membrane surfaces.

For OctC4, the NPN outer membrane assay displayed similar maximal levels as PmxB/colistin in E. coli, but required approximately 10-fold higher concentrations.[112] Similarly, the diSC3–5 membrane depolarization assay showed effects starting at a higher dose than PmxB/colistin, but with stronger fluorescence at higher concentrations. Uptake of Sytox® Green (nucleic acid stain), indicative of inner membrane permeabilization again required higher concentrations of OctC4 than the polymyxins for full cell permeabilization, but partial permeabilization was seen at similar concentrations.[112]

Neutron reflectometry studies of the interactions of octapeptin A3 with an asymmetric outer membrane model of resistant P. aeruginosa, clearly showed distinct differences from polymyxin B.[113] The bilayer was constructed using arabinose-modified lipid A isolated from a resistant P. aeruginosa strain for the outer leaflet, and 1,2-dipalmitoyl(d62)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (d-DPPC) for the inner leaflet. Polymyxin B bound to the Ara4N-modified lipid A headgroup, showing only surface binding effects, but while octapeptin A3 showed an initial transient polar interaction with the phospholipid/lipid A headgroups, this was followed by penetration of the entire molecule into the hydrophobic core of the outer membrane, showing interactions with both the lipid A and DPPC lipid tails, and demonstrating that octapeptins can bind to phospholipids independently of LPS. Indeed, release of dye from large unilamellar vesicles formed from PE/PG was induced by both OctA3 and polymyxin, but when P. aeruginosa LPS was added release was reduced in the case of OctA3, but enhanced for colistin [113] Similar effects were seen for OctC4, where POPC/POPG vesicles loaded with carboxyfluorescein were not permeabilised by either OctC4 or the polymyxins, but when E. coli LPS was added, PmxB/colistin induced high levels of leakage, while OctC4 caused little effect.[112]

In contrast to the above results essentially showing LPS-independent membrane activity of the octapeptins, isothermal titration calorimetry measurements showed a higher stoichiometry and binding affinity of Oct A3 to LPS (3:1, KD = 1.6 uM) compared to colistin (1.5:1 and KD = 5.6 uM); the stronger OctA3 binding was also supported by studies measuring displacement of a fluorescent polymyxin probe.[113] Similar effects were seen for OctC4 using surface plasmon resonance assessment of binding to L1 sensor chips coated with POPC, POPC/POPG (4:1) or POPC/E. coli lipid A (4:1); octapeptin bound slightly more strongly than PmxB or colistin to the POPC or POPC/POPG layers, but binding of all three was greatly enhanced with addition of lipid A, with OctC4 showing the strongest signal.[112]

A NMR structure determination of OctC4 and a decanoic acid acyl chain analog in the presence of a membrane mimetic, deuterated n-dodecylphosphocholine micelles, showed many more NOE cross-peaks than the solution structure.[112] Both structures were substantially more compact than PmxB, with the N-terminal fatty acid and the D-Phe-Leu segment forming a three-pronged hydrophobic triad which modelling indicates interact with the fatty acyl chains of lipid A. The octapeptin Dab residues interact with the lipid A Kdo2 sugars, rather than the phosphate contacts observed in the modelled polymyxin structure, potentially explaining why the aminoarabinose modifications in polymyxin-resistant strains do not affect octapeptin binding. Together, this data supports the differences in lipid binding seen with the OctA3 neutron reflectometry studies. [113] A solution NMR analysis of the linear OctB5 analog did not indicate any secondary structure.[107]

2.7. Resistance

Octapeptins have shown promising activity against clinical PmxR Gram-negative isolates suggesting an alternative mode of action (Table 2). This lack of cross-resistance was first noted by Meyers et al. in 1973.[97] However, potency against some intrinsically PmxR species including Proteus spp and Serratia marcescens is attenuated.[114] These species harbor a unique lipid A structure that potentially leads to the reduced octapeptin activity. Proteus spp. lipid A contains a diglucosamine backbone, two phosphate groups and are hepta-acylated with either 3-hydroxy-myristoyl, myristate or palmitoylate.[118] S. marcescens differ by penta- or hexa-acylation with a combination of 3-hydroxy-myristoyl or myristate.[119, 120] These species intrinsically fortify the negatively charged phosphate groups of lipid A with 4-amino-4-deoxy-arabinose (Ara4N) which neutralizes the negative charge and consequently, causes resistance to polymyxins. Conversely, octapeptins have shown reasonable activity against another intrinsically PmxR species, Burkholderia cepacia (MIC: 1.6 – 6.3 µg/ ml).[102] B. cepacia also possesses Ara4N modifications but is penta-acylated with 3-hydroxy-myristoyl or 3-hydroxy-palmitoyl.[121]

Table 2.

Activity and cytotoxicity of polymyxin B (PmxB), octapeptins A3, B5 and C4, and related octapeptin analogs

| Strain/cell linea |

PmxB | PmxE colistin | OctC4 | Linear OctC4[111] | OctC4 C-term-Thr [112] | OctC4 non-OH decanoic acid FA [112] | OctA3 [113] | OctB5 (Batticin) | OctB5 4-Me-hexanoyl[107] | linear OctB5 4-Me-hexanoyl[107] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-negative | MIC (µg/mL) | |||||||||

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | 0.25[111, 112] | 0.25[112] | 4[111, 112] | 16 | 2 | nd | ||||

| E. coli ATCC 35218 | 1[98] | 4[98] | ||||||||

| E. coli clinical isolates (5237,5353,5364,5539) | 0.5–1[98] | 2–4[98] | ||||||||

| E. coli DH5α* | (10–15 µM) [107] | (15–25 µM) | (2.5–5 µM) | |||||||

| K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883 | 0.25[111]; 1[112, 113] | 1[112, 113] | 8[111], 4[112] | >32 | 16 | 8 | 8 | |||

| K. pneumoniae ATCC 700603 ESBL | 0.25[111] | 8[111] | 16 | |||||||

| K. pneumoniae BAA-2146 NDM-1 | 0.25[111] | 8[111] | >32 | |||||||

| K. pneumoniae FADDI-KP032 | <0.125[112] | 1[112] | 4[112] | 2 | 2 | |||||

| K. pneumoniae M320445 | <0.125[113] | <0.125[113] | 4 | |||||||

| K. pneumoniae clinical isolates (5405,5147,5614) | 1[98] | 2–8[98] | ||||||||

| K. pneumoniae FADDI-KP027 | 128[112] | >128[112] | 16[112] | >32 | 16 | |||||

| K. pneumoniae FADDI-KP003 | >32[112] | 128[112] | 8[112] | >32 | 32 | |||||

| K. pneumoniae FADDI-KP012 | 16[112] | 32[112] | 8[112] | >32 | 8 | |||||

| K. pneumoniae #1 | 128[113] | 128[113] | 8 | |||||||

| K. pneumoniae 224-11-C | >32[113] | >32[113] | 8 | |||||||

| K. pneumoniae 248 | 16[113] | 16[113] | 8 | |||||||

| A. baumannii ATCC 19606 | 0.25[111], 1[112, 113] | 1 [112, 113] | 4[111], 8 [112] | >32 | >32 | >32 | 32 | |||

| A. baumannii 246–01-C.246 | 0.5[113] | 0.5[113] | 8 | |||||||

| A. baumannii ATCC 17978 | 1[112, 113] | 0.5[112, 113] | 4[112] | >32 | 8 | 8 | ||||

| A. baumannii FADDI-AB110 | 0.5 [112] | 0.5[112] | 8[112] | >32 | 4 | |||||

| A. baumannii clinical isolates (5064,5520,5383,5349,5075) | 1[98] | 4–16[98] | ||||||||

| A. baumannii ATCC 19606R | 128[113] | 128[113] | 32 | |||||||

| A. baumannii 07AC-336 | 8[113] | 16[113] | >32 | |||||||

| A. baumannii FADDI-AB065 | 128 [112] | 128 [112] | 16 [112] | >32 | 8 | |||||

| A. baumannii FADDI-AB156 | 8[112] | 16[112] | >32[112] | >32 | 8 | |||||

| A. baumannii FADDI-AB167 | 16[112] | 8[112] | 16[112] | >32 | 16 | |||||

| P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | 0.5[111], 2[98], 1[112, 113] | 1[112, 113] | 2[111] | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4[98] | ||

| P. aeruginosa FADDI-PA025 | 1[112] | 1[112] | 8[112] | 4 | 4 | |||||

| P. aeruginosa clinical isolates (5215,5313,5585,5298,5510) | 1–2[98] | 4[98] | ||||||||

| P. aeruginosa unspecified | (5–10 uM) [107] | (2.5–5 uM) | (1–2.5 uM) | |||||||

| P. aeruginosa PmxR FADDI-PA070 | 32[111, 112] | >128[112] | 2[111, 112] | 32 | 1 | 8 | ||||

| P. aeruginosa FADDI-PA060 | >32[112] | >128[112] | 2[112] | 2 | 4 | |||||

| P. aeruginosa FADDI-PA090 | 4[112] | 8[112] | 8[112] | 2 | 2 | |||||

| P. aeruginosa PmxR PA9704 | 128[111] | 2[111] | >32 | |||||||

| P. aeruginosa 19147 R | 32[113] | >128[113] | 1 | |||||||

| P. aeruginosa 18878B | >32[113] | >128[113] | 1 | |||||||

| P. aeruginosa M146201 | 4[113] | 8[113] | 1 | |||||||

| P. aeruginosa 19147n/m | >32[113] | >128[113] | 2 | |||||||

| Gram-positive | MIC (µg/mL) | |||||||||

| S. aureus ATCC 25923 MSSA | >64[111] | 16[111] | 32 | |||||||

| S. aureus ATCC 43300 MRSA | 100[98], >32[112] | >32[112] | 32[112] | >32 | 8 | 32 | 64–128[98] | |||

| S. aureus unspecified | (>50 uM) [107] | (101–507 uM) | (1–2.5 uM) | |||||||

| Fungi |

MIC (µg/mL) |

|||||||||

| C. albicans ATCC 90028 | >100[110] | >100[110] | ||||||||

| C. glabrata ATCC 90030 | >100[110] | >100[110] | ||||||||

| C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019 | >100[110] | >100[110] | ||||||||

| A. fumigatus ATCC MYA 3626 | >100[110] | >100[110] | ||||||||

| C. gattii MMRL 2651 | 25[110] | 3.1[110] | ||||||||

| C. neoformans H99, ATCC 90113, H99 | 12.5–50[110] | 1.56–6.25[110] | ||||||||

| Cytotoxicity (LDH or MTT assay) | CC50 (µM) | |||||||||

| HEK293 | >128 [98] | |||||||||

| HK2 (10% FBS) | 135[111] | 31[111] | 139 | |||||||

| hRPTEC (10% FBS) | >300[111] | 39[111] | 71 | |||||||

note this a cell line used normally for cloning transformation

Studies addressing the potential mechanism/s of resistance against octapeptins remain scarce. Meyers et al. observed no resistance after ten passages with EM49 (a combination of octapeptin classes A and B) for P. aeruginosa, E. coli, S. aureus and C. albicans.[99] Pitt et al.[122] recently conducted studies to discern the progression of resistance against polymyxins and OctC4 in an XDR polymyxin-susceptible K. pneumoniae clinical isolate. This strain was grown in the presence of sub-lethal doses of colistin, PmxB or OctC4 over 20 days of daily passage, with the MIC determined daily and the sub-lethal dose (one 2-fold dilution below MIC) adjusted accordingly. The induction was followed by 5 days without exposure to antibiotic to examine the genetic stability of the induced resistance. For OctC4, only a subtle increase in resistance was consistently observed across eight replicates after 20 days (MIC increase 4- fold), which differed drastically compared to both polymyxins (MIC increase >1000-fold, generally occurring by day 15 in all replicates). All resistance was stable and, significantly, no cross-resistance was apparent (octapeptin-induced strains retained sensitivity to the polymyxins, and polymyxin-induced strains were octapeptin-susceptible). Whole genome sequencing revealed no similar mutations between the two antibiotic classes, while colistin and PmxB results were similar. For polymyxin resistance, two-component regulatory systems PmrAB and PhoPQ including the negative regulator, MgrB, were predominantly impacted. OctC4-induced isolates contained mutations in mlaD, mlaF and pqiB. These genes are critical for outer membrane asymmetry and phospholipid removal.[123, 124] These findings further validate an alternative mode of action between polymyxins and octapeptins. Notably, the format in which this induced resistance experiment is conducted allows for potential heteroresistance to appear, as mixed populations in broth are used at every stage of the induction (i.e. no individual colony picking).

3. Conclusions

The octapeptins are a ‘rediscovered’ class of lipopeptide antibiotics, first reported in the 1970s. While structurally similar to the clinically important polymyxin antibiotics, the octapeptins somewhat surprisingly retain activity against polymyxin-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. This is particularly important, as the polymyxins have become ‘last-resort’ antibiotics for extensively drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria, yet there are now widespread reports of polymyxin resistance. Since 2015, the first chemical syntheses of three of the natural octapeptins have been described, along with initial attempts at developing structure-activity relationships by preparing small sets of related analogs. For at least one of the natural octapeptins (octapeptin B5), a linear version retained antimicrobial activity. The octapeptins also have increased activity against Gram-positive bacteria and fungi, compared to the polymyxins.

These new reports of octapeptin activity have also explored their mode of action, again with comparison to how the polymyxins act. While both classes exhibit binding to membrane component lipid A, the octapeptins apparently insert more strongly into the outer membrane independently of their lipid A affinity, allowing them to remain active when lipid A is modified to block polymyxin binding. The octapeptins also have less propensity to induce resistance, with no cross-reactivity to the polymyxins, a significant advantage given the advent of rapidly disseminated resistance elements such as mcr-1 that will further compromise the potential clinical value of agents possessing a similar mode of action to colistin. The octapeptins exhibit in vivo efficacy in multiple mouse models of infection, and may show reduced nephrotoxicity compared to the polymyxins, which would provide additional superiority.

In summary, the octapeptins are promising alternate therapies to colistin/polymyxins with a different mode of action, spectra of antimicrobial action and potentially different risk profile. However, they are currently early stage antibiotic candidates that require extensive development and time before reaching the clinic. A better understanding of the toxicology profile of the octapeptins, their spectra of action, and further examination of the mode of action of this drug class could together provide sufficient evidence to drive new compounds into the clinic to combat the threat of untreatable MDR and XDR Gram-negative infections.

4. Expert Commentary

Prior attempts to derive new antibiotics from the lipopeptide class have focused solely on the colistin core scaffold, but this class may possess some inherent liabilities, namely a propensity for rapid development of resistance, and potential for nephrotoxicity.

Kidney damage is a major side effect of many drugs. A significant proportion of investigational drugs fail in clinical trials due to nephrotoxicity, with an analysis of the AstraZeneca pipeline showing 9% of the 52% clinical failures due to renal issues (and 8% of the 82% of projects failing at the preclinical stage).[126] Across all drugs (not just antibiotics), approximately 20 percent of community-and hospital-acquired episodes of acute renal failure are related to drug use.[127, 128] Colistin / polymyxins are significantly nephrotoxic drugs that cause great harm in humans. While polymyxin nephrotoxicity is generally considered reversible in most patients, it limits the ability to achieve therapeutic doses of antibiotic. Patients that do recover from infection may be left with severely impaired renal function that ultimately affects quality and length of life. There are currently a number of clinical studies attempting to improve the dosing regimen of the polymyxins to reduce kidney injury, but the margin of safety between doses high enough for efficacy (particularly in the face of growing resistance) but low enough not to cause damage appears to be very narrow. This is coupled with remarkably rapid and large (>100-fold increase in MIC) induction of resistance by sub-optimal therapy, as shown by in vitro induced resistance studies, potentially occurring within a patient during a two-week course of treatment.

Past attempts to engineer improvements to colistin in both academia and industry have generally failed at even earlier stages than drugs in general. One key failure mode is the paucity of in vitro or in vivo pre-clinical predictive models of human nephrotoxicity.[129] Candidate drugs from Cubist, Pfizer and AstraZeneca have not been able to progress into the clinic primarily due to nephrotoxicity issues. This is partly because within this chemotype class animal nephrotoxicity does not appear to correlate well with human nephrotoxicity. Considerable effort has been invested in trying to develop better predictive in vitro models of nephrotoxicity, such as testing a range of kidney damage biomarkers in different parental and immortalized human cell lines[117] or cloning clinically validated human biomarkers of nephrotoxicity [130] into Zebra fish.[131]

It is clear that the octapeptins have strikingly different activity profiles to the polymyxins. This is manifested in their activity against polymyxin-resistant bacteria, their greatly reduced propensity to induce resistance compared to polymyxins B/E, and the complete lack of cross-resistance between resistant strains induced by octapeptins or polymyxins. Mode of action studies reveal subtle variations in membrane-disrupting effects between the polymyxins and octapeptins, with lipid A-independent membrane-disrupting effects seen with the octapeptins. Nevertheless, both classes have an affinity for lipid A, and as such the ability of the octapeptins to overcome lipid A modifications is quite remarkable.

Together, these properties support consideration of the octapeptins as a lipopeptide class that is distinct from the polymyxins. The potential clinical utility, albeit many years in the future, of the octapeptins is supported by evidence of a reduced toxicity / nephrotoxicity liability, at least in initial in vitro and mouse studies. Whether this translates into an improved therapeutic index, particularly in humans, is the key question that remains to be answered. The octapeptins also demonstrate that a systematic review of ‘forgotten’ antibiotics merits further examination.

5. Five-year view

In five years it can be confidently predicted that a great deal more will be known about the octapeptins. The research programs currently underway by at least three academic groups will have established a more advanced understanding of their structure-activity and structure-toxicity relationships, and in vivo efficacy and toxicity will be clearly defined. Ideally, at least one candidate will have advanced through preclinical testing and entered Phase 1 clinical trials to demonstrate safety, answering the key question of whether the octapeptins actually fundamentally differ from the polymyxins in their nephrotoxicity, and whether they possess genuine therapeutic potential in humans. More fundamentally, this ‘case study’ on a forgotten antibiotic class should spur similar efforts to discover ‘forgotten’ antibiotics left on the shelf in the golden age of discovery when we were spoilt for choice. We unfortunately now have very, very few choices left.

6. Key issues:

The octapeptins are a class of lipopeptides with antimicrobial activity, including against polymyxin-resistant bacteria, with potential to treat XDR Gram-negative infections.

The octapeptins require further investigation to establish their ability to treat XDR Gram-negative infections, specifically demonstration of more comprehensive MIC90 against resistant clinical isolates, and efficacy against resistant strains in in vivo models.

Critically, the octapeptins should not exhibit the clinical nephrotoxicity, which has plagued next-generation versions of the polymyxins and prevented their development as drugs.

Experimental evidence supports the octapeptins acting by mechanisms fundamentally different from the polymyxins, including a lack of cross-resistance in resistance-induction studies.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The manuscript was funded by the Department of Health, Australian Government, National Health and Medical Research Council through the following grants; APP1005350, APP1045326, APP1059354, APP1139609 and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases through the following grants; R21AI098731/R33AI098731-03.

Declaration of Interest

MATB has patent applications relating to lipopeptide antibiotics relevant to the subject matter. MAC has patent applications relating to lipopeptide antibiotics relevant to the subject matter described in this manuscript and is involved in commercialization activities related to antibiotics. MAC currently holds a fractional Professorial Research Fellow appointment at the University of Queensland with his remaining time as CEO of Inflazome Ltd. a company headquartered in Dublin, Ireland that is developing drugs to address clinical unmet needs in inflammatory disease by targeting the inflammasome. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Footnotes

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Reference annotations

* Of interest

** Of considerable interest

References

- 1.Schwarz S, Johnson AP. Transferable resistance to colistin: a new but old threat. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016;71(8):2066–2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Theuretzbacher U Global antimicrobial resistance in Gram-negative pathogens and clinical need. Curr Opin Microbiol 2017;39:106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta N, Limbago BM, Patel JB, et al. Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae: Epidemiology and Prevention. Clin Infect Dis 2011;53(1):60–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.da Silva RM, Traebert J, Galato D. Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC)-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: a review of epidemiological and clinical aspects. Exp Opin Biol Ther 2012;12(6):663–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Souli M, Galani I, Giamarellou H. Emergence of extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli in Europe. Euro Surveill 2008;13(47):pii=19045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suwantarat N, Carroll KC. Epidemiology and molecular characterization of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria in Southeast Asia. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2016;5:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Duin D, Kaye KS, Neuner EA, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a review of treatment and outcomes. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2013;75(2):115–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guh AY, Limbago BM, Kallen AJ. Epidemiology and prevention of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in the United States. Exp Rev Anti-Infect Ther 2014;12(5):565–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nordmann P, Poirel L. The difficult-to-control spread of carbapenemase producers among Enterobacteriaceae worldwide. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014;20(9):821–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naas T, Cuzon G, Villegas MV, et al. Genetic structures at the origin of acquisition of the beta-lactamase bla(KPC) gene. Antimicrob Agents Ch 2008;52(4):1257–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fomda BA, Khan A, Zahoor D. NDM-1 (New Delhi metallo beta lactamase-1) producing Gram-negative bacilli: Emergence & clinical implications. Ind J Med Res 2014;140(5):672–678. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Livermore DM, Warner M, Mushtaq S, et al. What remains against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae? Evaluation of chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, colistin, fosfomycin, minocycline, nitrofurantoin, temocillin and tigecycline. Int J Antimicrob Agent 2011;37(5):415–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumarasamy KK, Toleman MA, Walsh TR, et al. Emergence of a new antibiotic resistance mechanism in India, Pakistan, and the UK: a molecular, biological, and epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis 2010;10(9):597–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falagas ME, Kasiakou SK. Colistin: the revival of polymyxins for the management of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. Clin Infect Dis 2005;40(9):1333–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keirstead ND, Wagoner MP, Bentley P, et al. Early Prediction of Polymyxin-Induced Nephrotoxicity With Next-Generation Urinary Kidney Injury Biomarkers. Toxicol Sci 2014;137(2):278–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falagas ME, Rafailidis PI, Matthaiou DK. Resistance to polymyxins: Mechanisms, frequency and treatment options. Drug Resist Updates 2010;13(4–5):132–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biswas S, Brunel JM, Dubus JC, et al. Colistin: an update on the antibiotic of the 21st century. Exp Rev Anti-Infective Ther 2012;10(8):917–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Srinivas P, Rivard K. Polymyxin Resistance in Gram-negative Pathogens. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2017;19(11):38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wenzler E, Bunnell KL, Danziger LH. Clinical use of the polymyxins: the tale of the fox and the cat. Int J Antimicrob Agent 2018:in press: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Matthaiou DK, Michalopoulos A, Rafailidis PI, et al. Risk factors associated with the isolation of colistin-resistant gram-negative bacteria: a matched case-control study. Crit Care Med 2008;36(3):807–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davies M, Walsh TR. A colistin crisis in India. Lancet Infect Dis 2018:in press: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30072–0. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Chen L, Todd R, Kiehlbauch J, et al. Notes from the Field: Pan-Resistant New Delhi Metallo-Beta-Lactamase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae - Washoe County, Nevada, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66(1):33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baron S, Hadjadj L, Rolain JM, et al. Molecular mechanisms of polymyxin resistance: knowns and unknowns. Int J Antimicrob Agent 2016;48(6):583–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castanheira M, Griffin MA, Deshpande LM, et al. Detection of mcr-1 among Escherichia coli clinical isolates collected worldwide as part of the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program during 2014–2015. Antimicrob Agents Ch 2016;60(9):5623–5624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tapsall JW. Antibiotic Resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41(Supplement 4):S263–S268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Unemo M, Nicholas RA. Emergence of multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and untreatable gonorrhea. Future Microbiol 2012;7(12):1401–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yin Y-P, Han Y, Dai X-Q, et al. Susceptibility of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to azithromycin and ceftriaxone in China: A retrospective study of national surveillance data from 2013 to 2016. PLOS Med 2018;15(2):e1002499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The World Health Organizatrion, The WHO Global Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Programme 2017 [Feb 14 2018]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2017/Antibiotic-resistant-gonorrhoea/en/

- 29.Butler MS, Blaskovich MA, Cooper MA. Antibiotics in the clinical pipeline at the end of 2015. J Antibiot 2017;70(1):3–24.**Comprehensive review of the current antibiotics in the clinical pipeline

- 30.Fernandes P, Martens E. Antibiotics in late clinical development. Biochem Pharmacol 2017;133:152–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The Pew Charitable Trusts, Antibiotics Currently in Global Clinical Development 2014, updated Dec 2017 [Jan 28 2018]. Available from: http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/multimedia/data-visualizations/2014/antibiotics-currently-in-clinical-development**Comprehensive review of the current antibiotics in the clinical pipeline

- 32.World Health Organization, Antibacterial Agents in Clinical Development: An Analysis of the Antibacterial Clinical Development Pipeline, Including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, WHO/EMP/IAU/2017 12 2017 [Jan 28 2018]. Available from: http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/rational_use/antibacterial_agents_clinical_development/en/**Comprehensive review of the current antibiotics in the clinical pipeline

- 33.Shlaes DM. Research and Development of Antibiotics: The Next Battleground. ACS Infect Dis 2015;1(6):232–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benedict RG, Langlykke AF. Antibiotic activity of Bacillus polymyxa. J Bacteriol 1947;54(1):24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stansly PG, Schlosser ME. Studies on polymyxin: Isolation and identification of Bacillus polymyxa and differentiation of polymyxin from certain known antibiotics. J Bacteriol 1947;54(5):549–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stansly PG, Shepherd RG, White HJ. Polymyxin: a new chemotherapeutic agent. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp 1947;81(1):43–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ainsworth GC, Brown AM, Brownlee G. Aerosporin, an antibiotic produced by Bacillus aerosporus Greer. Nature 1947;159(4060):263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koyama Y, Kurosasa A, Tsuchiya A, et al. A new antibiotic ‘colistin’ produced by spore-forming soil bacteria. J Antibiotics 1950;3:457–458. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shoji J, Hinoo H, Wakisaka Y, et al. Isolation of two new polymyxin group antibiotics. Studies on antibiotics from the genus Bacillus. XX. J Antibiotics 1977;30(12):1029–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shoji J, Kato T, Hinoo H. The structure of polymyxin S. Studies on antibiotics from the genus Bacillus. XXI. J Antibiotics 1977;30(12):1035–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilkinson S, Lowe LA. Structures of the polymyxins A and the question of identity with the polymyxins M. Nature 1966;212(5059):311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parker WL, Rathnum ML, Dean LD, et al. Polymyxin E, a new peptide antibiotic. J Antibiotics 1977;30(9):767–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shoji J, Kato T, Hinoo H. The structure of polymyxin T1. Studies on antibiotics from the genus Bacillus. XXII. J Antibiotics 1977;30(12):1042–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Terabe S, Konaka R, Shoji Ji. Separation of polymyxins and octapeptins by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatography A 1979;173(2):313–320. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brink AJ, Richards GA, Colombo G, et al. Multicomponent antibiotic substances produced by fermentation: implications for regulatory authorities, critically ill patients and generics. Int J Antimicrob Agent 2014;43(1):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cui AL, Hu X-X, Gao Y, et al. The Synthesis and Bioactivity Investigation of the Individual Components of Cyclic Lipopeptide Antibiotics. J Med Chem 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Orwa JA, Govaerts C, Busson R, et al. Isolation and structural characterization of polymyxin B components. J Chromatography A 2001;912(2):369–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Orwa JA, Govaerts C, Busson R, et al. Isolation and structural characterization of colistin components. J Antibiot 2001;54(7):595–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stansly PG. The polymyxins; a review and assessment. Am J Med 1949;7(6):807–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spapen H, Jacobs R, Van Gorp V, et al. Renal and neurological side effects of colistin in critically ill patients. Ann Intensive Care 2011;1(1):14, doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mendes CA, Burdmann EA. Polymyxins - review with emphasis on nephrotoxicity. Revista da Associacao Medica Brasileira (1992) 2009;55(6):752–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zavascki AP, Nation RL. Nephrotoxicity of Polymyxins: Is There Any Difference between Colistimethate and Polymyxin B? Antimicrob Agents Ch 2017;61(3):in press: doi: 10.1128/AAC.02319-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Justo JA, Bosso JA. Adverse Reactions Associated with Systemic Polymyxin Therapy. Pharmacotherapy: J Human Pharmacol Drug Ther 2015;35(1):28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kelesidis T, Falagas ME. The safety of polymyxin antibiotics. Exp Opin Drug Safety 2015;14(11):1687–1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Velkov T, Roberts KD, Nation RL, et al. Pharmacology of polymyxins: new insights into an ‘old’ class of antibiotics. Future Microbiol 2013;8(6):711–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kadar B, Kocsis B, Nagy K, et al. The renaissance of polymyxins. Curr Med Chem 2013;20(30):3759–3773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deris ZZ, Akter J, Sivanesan S, et al. A secondary mode of action of polymyxins against Gram-negative bacteria involves the inhibition of NADH-quinone oxidoreductase activity. J Antibiot 2014;67(2):147–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kassamali Z, Rotschafer JC, Jones RN, et al. Polymyxins: wisdom does not always come with age. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57(6):877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nation RL, Li J. Colistin in the 21st century. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2009;22(6):535–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Biswas S, Brunel JM, Dubus JC, et al. Colistin: an update on the antibiotic of the 21st century. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2012;10(8):917–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sorlí L, Luque S, Grau S, et al. Trough colistin plasma level is an independent risk factor for nephrotoxicity: a prospective observational cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 2013;13(1):380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nation RL, Li J, Cars O, et al. Framework for optimisation of the clinical use of colistin and polymyxin B: the Prato polymyxin consensus. Lancet Infect Dis 15(2):225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Couet W, Gregoire N, Marchand S, et al. Colistin pharmacokinetics: the fog is lifting. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012;18(1):30–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Garonzik SM, Li J, Thamlikitkul V, et al. Population Pharmacokinetics of Colistin Methanesulfonate and Formed Colistin in Critically Ill Patients from a Multicenter Study Provide Dosing Suggestions for Various Categories of Patients. Antimicrob Agents Ch 2011;55(7):3284–3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Landersdorfer CB, Nation RL. Colistin: How should It Be Dosed for the Critically Ill? Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2015;36(01):126–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vattimo MdFF, Watanabe M, da Fonseca CD, et al. Polymyxin B Nephrotoxicity: From Organ to Cell Damage. PLOS ONE 2016;11(8):e0161057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Abdelraouf K, Braggs KH, Yin T, et al. Characterization of Polymyxin B-Induced Nephrotoxicity: Implications for Dosing Regimen Design. Antimicrob Agents Ch 2012;56(9):4625–4629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kwon J-A, Lee JE, Huh W, et al. Predictors of acute kidney injury associated with intravenous colistin treatment. Int J Antimicrob Agents 35(5):473–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ouderkirk JP, Nord JA, Turett GS, et al. Polymyxin B Nephrotoxicity and Efficacy against Nosocomial Infections Caused by Multiresistant Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Ch 2003;47(8):2659–2662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pogue JM, Lee J, Marchaim D, et al. Incidence of and Risk Factors for Colistin-Associated Nephrotoxicity in a Large Academic Health System. Clin Infect Dis 2011;53(9):879–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hartzell JD, Neff R, Ake J, et al. Nephrotoxicity Associated with Intravenous Colistin (Colistimethate Sodium) Treatment at a Tertiary Care Medical Center. Clin Infect Dis 2009;48(12):1724–1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zavascki AP, Nation RL. Nephrotoxicity of Polymyxins: Is There Any Difference between Colistimethate and Polymyxin B? Antimicrob Agents Ch 2017;61(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yousef JM, Chen G, Hill PA, et al. Melatonin Attenuates Colistin-Induced Nephrotoxicity in Rats. Antimicrob Agents Ch 2011;55(9):4044–4049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yousef JM, Chen G, Hill PA, et al. Ascorbic acid protects against the nephrotoxicity and apoptosis caused by colistin and affects its pharmacokinetics. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012;67(2):452–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Holloway KP, Rouphael NG, Wells JB, et al. Polymyxin B and Doxycycline Use in Patients with Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infections in the Intensive Care Unit. Ann Pharmacother 2006;40(11):1939–1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Grill MF, Maganti RK. Neurotoxic effects associated with antibiotic use: management considerations. Brit J Clin Pharmacol 2011;72(3):381–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Storm DR, Rosenthal KS, Swanson PE. Polymyxin and related peptide antibiotics. Annu Rev Biochem 1977;46:723–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Velkov T, Thompson PE, Nation RL, et al. Structure-activity relationships of polymyxin antibiotics. J Med Chem 2010;53(5):1898–1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Velkov T, Roberts KD, Thompson PE, et al. Polymyxins: a new hope in combating Gram-negative superbugs? Fut Med Chem 2016;8(10):1017–1025.** A good review summarising polymyxin class of lipopeptides

- 80.Vaara M Novel derivatives of polymyxins. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013;68(6):1213–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vaara M, Lister T, Zabawa T, et al. Polymyxins targeting the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. Med Chem Rev 2016;51:243–260. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vaara M New polymyxin derivatives that display improved efficacy in animal infection models as compared to Polymyxin B and colistin. Medicinal research reviews 2018;38:under review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brown P, Dawson MJ. Development of new polymyxin derivatives for multi-drug resistant Gram-negative infections. J Antibiot 2017;70:386–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rabanal F, Cajal Y. Recent advances and perspectives in the design and development of polymyxins. Nat Prod Rep 2017;34(7):886–908.* A review of advances in the development of new polymyxin antibiotics

- 85.Cochrane SA, Vederas JC. Lipopeptides from Bacillus and Paenibacillus spp.: A Gold Mine of Antibiotic Candidates. Med Res Rev 2016;36(1):4–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rabanal F, Grau-Campistany A, Vila-Farrés X, et al. A bioinspired peptide scaffold with high antibiotic activity and low in vivo toxicity. Sci Rep 2015;5:10558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gallardo-Godoy A, Muldoon C, Becker B, et al. Activity and Predicted Nephrotoxicity of Synthetic Antibiotics Based on Polymyxin B. J Med Chem 2016;59(3):1068–1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Coleman S, Deats T, Pawliuk R, et al. Poster F-1630/302 CB-182,804 is Less Nephrotoxic as Compared to Polymyxin B in Monkeys Following Seven Days of Repeated Intravenous Dosing. 50th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy; Boston, MA, USA2010. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Arya A, Li T, Zhang S, et al. Poster F-1627/299 Efficacy of CB-182,804, a Novel Polymyxin Analog, in Rat and Mouse Models of Gram-Negative Bacterial Infections. 50th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy; Boston, MA, USA 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Magee TV, Brown MF, Starr JT, et al. Discovery of Dap-3 Polymyxin Analogues for the Treatment of Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Nosocomial Infections. J Med Chem 2013;56(12):5079–5093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Velkov T, Thompson PE, Nation RL, et al. Structure--activity relationships of polymyxin antibiotics. J Med Chem 2010;53(5):1898–1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.McCoy LS, Roberts KD, Nation RL, et al. Polymyxins and analogues bind to ribosomal RNA and interfere with eukaryotic translation in vitro. Chembiochem 2013;14(16):2083–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Olaitan AO, Morand S, Rolain J-M. Mechanisms of polymyxin resistance: acquired and intrinsic resistance in bacteria. Front Microbiol 2014;5:643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Poirel L, Jayol A, Nordmann P. Polymyxins: Antibacterial Activity, Susceptibility Testing, and Resistance Mechanisms Encoded by Plasmids or Chromosomes. Clin Microbiol Rev 2017;30(2):557–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Stojanoski V, Sankaran B, Prasad BV, et al. Structure of the catalytic domain of the colistin resistance enzyme MCR-1. BMC Biol 2016;14(1):81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Han M-L, Velkov T, Zhu Y, et al. Polymyxin-Induced Lipid A Deacylation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Perturbs Polymyxin Penetration and Confers High-Level Resistance. ACS Chem Biol 2018;13(1):121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Meyers E, Brown WE, Principe PA, et al. EM49, a new peptide antibiotic. I. Fermentation, isolation, and preliminary characterization. J Antibiot 1973;26(8):444–448.* The first reports of the octapeptins

- 98.Qian CD, Wu XC, Teng Y, et al. Battacin (Octapeptin B5), a new cyclic lipopeptide antibiotic from Paenibacillus tianmuensis active against multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012;56(3):1458–65.* First report in 20 years of a new member of the octapeptin

- 99.Meyers E, Pansy FE, Basch HI, et al. EM49 - New peptide antibiotic III. Biological characterization in vitro and in vivo. J Antibiot 1973;26(8):457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Parker WL, Rathnum ML. EM49 - new peptide antibiotic II. Chemical characterization. J Antibiot 1973;26(8):449–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Meyers E, Parker WL, Brown WE, et al. EM49 - new polypeptide antibiotic active against cell-membranes. Annal New York Acad Sci 1974;235:493–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Konishi M, Sugawara K, Tomita K, et al. Bu-2470, a new peptide antibiotic complex. I. Production, isolation and properties of Bu-2470 A, B1 and B2. J Antibiot 1983;36(6):625–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Parker WL, Rathnum ML. EM49, a new peptide antibiotic IV. The structure of EM49. J Antibiot 1975;28(5):379–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sugawara K, Yonemoto T, Konishi M, et al. Bu-2470, a new peptide antibiotic complex. II. Structure determination of Bu-2470 A, B1, B2a and B2b. J Antibiot 1983;36(6):634–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Meyers E, Parker WL, Brown WE. A nomenclature proposal for the octapeptin antibiotics. J Antibiot 1976;29(11):1241–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kawaguchi H, Tsukiura H, Fujiawa K-i, et al. , inventors; Bristol-Myers Company, assignee Antibiotic BU-1880 patent US3880994.

- 107.De Zoysa GH, Cameron AJ, Hegde VV, et al. Antimicrobial peptides with potential for biofilm eradication: synthesis and structure activity relationship studies of battacin peptides. J Med Chem 2015;58(2):625–639.* First synthesis of octapeptin B5

- 108.De Zoysa GH, Sarojini V. Feasibility Study Exploring the Potential of Novel Battacin Lipopeptides as Antimicrobial Coatings. ACS Appl Mater Interface 2017;9(2):1373–1383.* First synthesis of octapeptin B5

- 109.De Zoysa GH, Glossop HD, Sarojini V. Unexplored antifungal activity of linear battacin lipopeptides against planktonic and mature biofilms of C. albicans. Eur J Med Chem 2018;146:344–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]