ABSTRACT

Background and Methods

Mutations in WDR45 cause β‐propeller protein‐associated neurodegeneration (BPAN), a type of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA). We reviewed clinical and MRI findings in 4 patients with de novo WDR45 mutations.

Results

Psychomotor delay and movement disorders were present in all cases; early‐onset epileptic encephalopathy was present in 3. In all cases, first MRI showed: prominent bilateral SN enlargement, bilateral dentate nuclei T2‐hyperintensity, and corpus callosum thinning. Iron deposition in the SN and globus pallidus (GP) only became evident later. Diffuse cerebral atrophy was present in 3 cases.

Conclusions

In this series, SN swelling and dentate nucleus T2 hyperintensity were early signs of BPAN, later followed by progressive iron deposition in the SN and GP. When clinical suspicion is raised, MRI is crucial for identifying early features suggesting this type of NBIA.

Keywords: neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation, NBIA, BPAN, magnetic resonance imaging, substantia nigra, parkinsonism

Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA) is a heterogeneous group of rare disorders characterized by abnormal progressive iron accumulation in the basal ganglia, movement disorders, and cognitive disability.1 Estimated prevalence is 1 to 3 per million.2

NBIA etiologies remain largely unknown, but an increasing number of inherited or de novo single‐gene mutations, not always clearly involved in iron homeostasis, have been associated with these conditions.3 The WDR45 gene on chromosome Xp11.234 encodes the WIPI4 protein (WD40‐repeat protein interacting with phosphoinositides‐4). All WD40‐repeat proteins are thought to form a circularized beta‐propeller scaffold for interactions with other proteins. WIPI4 itself is involved in the autophagy pathway, iron storage, and ferritin metabolism.5 Mutations in WIPI4 result in the NBIA disorder known as β‐propeller protein‐associated neurodegeneration (BPAN).6 BPAN is characterized by heterogeneous phenotypic expression, probably in relation to different WDR45 alterations (around 50 have been described so far), but likely also as a result of randomized X‐chromosome inactivation in females.7 Iron deposition in the SN and globus pallidus (GP) is a diagnostic marker for BPAN, but only becomes evident some years after disease onset, so the disease is often diagnosed rather late.

We report clinical and MRI findings in 4 young patients with de novo WDR45 mutations, in whom the revaluation of first MRI showed unusual and potentially diagnostic signs of the disease.

Case Presentation

MRI findings are summarized in Table 1. MRI examinations were performed on a 1.5T unit (Magnetom Avanto; Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) with an eight‐channel head coil. The imaging protocol included standard sequences and: (1) 3D T1‐weighted (T1w) magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) on the axial plane with multiplanar reconstruction (192 slices; repetition time [TR], 2000 ms; echo time [TE], 2 ms; thickness, 0.9 mm; flip angle [FA], 15 degrees; phase I > S; matrix, 576 × 576; 1 average); (b) coronal T2‐weighted (T2w) turbo spin echo ( 50 slices; TR, 4100 ms; TE, 120 ms; thickness, 3.00 mm; FA, 90 degrees; phase A > P; matrix, 444 × 444; 2 averages); (c) axial T2w fast‐field echo (FFE; 19 slices; TR, 1120 ms; TE, 25 ms; thickness,,3.00 mm; FA, 18 degrees; phase I > S; matrix, 288 × 288; 2 averages).

Table 1.

MRI findings in 4 patients with a WDR45 gene mutation

| Patient | Date of Birth | Sex | Age at MRI | SN | Globus Pallidus | Corpus Callosum | Halo Sign on T1‐WI | Dentate Nuclei on T2‐WI | Cerebral Atrophy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 09/04/11 | F | 4y 6mo | Swollen; no iron | Normal | Thinning | Absent | Hyperintensity | Normal sulci; enlarged ventricles; asymmetry (left>right) |

| 6y 6mo | Swollen; iron deposition | Iron deposition | Thinning | Absent | Hyperintensity | Normal sulci; enlarged ventricles; asymmetry (left>right) | |||

| 2 | 09/08/03 | F | 9y 3mo | Swollen; no iron | Normal | Thinning | Absent | Hyperintensity | Enlarged sulci and ventricles; asymmetry (left>right); abnormal hippocampi |

| 12y 7mo | Swollen; iron deposition | Iron deposition | Thinning | Absent | Hyperintensity | Enlarged sulci and ventricles; asymmetry (left>right); abnormal hippocampi | |||

| 3 | 23/02/10 | F | 1y 5mo | Swollen; no iron | Normal | Marked thinning | Present | Hyperintensity | Enlarged sulci and ventricles; asymmetry (left>right); abnormal hippocampi |

| 7y 8mo | Swollen; iron deposition | Iron deposition | Marked thinning | Present | Hyperintensity | Enlarged sulci and ventricles; asymmetry (left>right); abnormal hippocampi | |||

| 4 | 12/06/13 | F | 1 mo | Swollen; no iron | Normal | Thinning | Absent | Hyperintensity | Enlarged sulci and ventricles; asymmetry (left>right); abnormal hippocampi |

| 3y 9mo | Swollen; iron deposition | Iron deposition | Thinning | Absent | Hyperintensity | Enlarged sulci and ventricles; asymmetry (left>right); abnormal hippocampi |

Abbreviation: WI, weighted images.

Case 1

A 6‐year‐old female was referred to us for psychomotor retardation. Neurological examination showed mild cognitive impairment, autonomous gait requiring unilateral support, stereotypic hand movements, and impaired fine motor praxis; language delay, dysarthria, and dysphonia were also present. Neither electroencephalographic abnormalities nor alterations at routine biochemical analysis were found. Brain MRI at 6 years 6 months showed bilateral symmetric T2w and T2* hypointensity in the SN, and, less marked, in the ventral GP, with swollen SN (Fig. 1E,F). These findings were not present in the previous MRI at 4 years 6 months, which was reported normal (Fig. 1A,B). Review of this initial exam showed an unusually enlarged SN (Fig. 1C) and slight hyperintensity on T2‐w.i. in both dentate nuclei (DN; Fig. 1G). These findings, together with the clinical data, led to the suspicion of NBIA. When tested for mutations, the patient was found positive for a de novo deletion in WDR45, c.921delA(p.Ala308Leufs*22), permitting the diagnosis of BPAN.

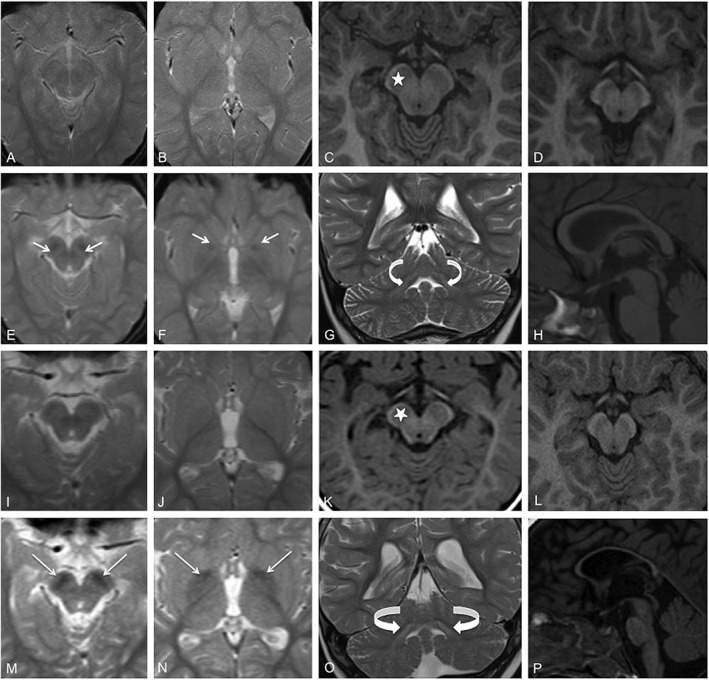

Figure 1.

Brain MRI of patient 1 (A–C and E–H), at 4 years 6 months (A–C) and 6 years 6 months (E–H). On T2‐FFE at 6 years 6 months, bilateral symmetric hypointensity is visible in the SN and, to a lesser extent, the ventral GP (white arrows in E and F), but is not evident in scans at 4 years 6 months (A,B). The SN enlargement on T1 MPRAGE in C (star) is to be compared with the same area in a normal sex‐ and aged‐matched control (D). Slight symmetric hyperintensity is evident in the DN (curved arrows in G) in T2, and moderate corpus callosum thinning is evident on T1 (H). MRI scans of patient 3 (I–K and M–P), at ages 17 months (I–K) and 7 years 8 months (M–P), show closely similar findings to those in patient 1. At 7 years 8 months, T2‐FFE shows bilateral hypointensity in the SN and GP (white arrows, M and N), that is not evident on the earlier scans MRI (I,J). SN enlargement is evident on T1 MPRAGE in K (star) that is not present in a normal sex‐ and aged‐matched control (L). On T2, there is symmetric hyperintensity in the DN (curved arrows in O) and marked thinning of the corpus callosum (P). Strongest GP hypointensity is present in anteriorly and medially (N).

Case 2

A 13‐year‐old female was referred to us for delayed psychomotor development and epileptic encephalopathy. Epilepsy onset was at 18 months with focal seizures and spasms. Brain MRI at 2 years 8 months, not available, was reported as normal. At 6 years, onset of cortical myoclonus and parkinsonism were reported.

The patient underwent karyotype, CGH array, and genetic screening for early‐onset epileptic encephalopathy with Rett syndrome phenotype (CDKL5, MECP2, UBE3A, and STXBP1) with negative results. Metabolic tests and other examinations to investigate hypothesized progressive infantile poliodystrophy (PLA2G6, PANK2, and CNL10, with neuropathological ultrastructural study of skin) were unrevealing. Neurological evaluation at 9 years 3 months showed cognitive delay with absence of language, myoclonic hyperkinesias, and prominent parkinsonism (dystonic posturing of hands). A second brain MRI showed diffuse atrophy, corpus callosum thinning, and DN hyperintensity; no iron deposition was detected in the SN or GP, but SN enlargement was evident. Because of worsening epilepsy, a new MRI was performed at 12 years 7 months, which showed bilateral symmetric T2w and T2* hypointensity in the SN and ventral GP. Screening for mutations in NBIA genes revealed a de novo substitution on WDR45, c.479T>G (p.Leu160Arg).

Case 3

An 8‐year‐old female came to our attention with psychomotor retardation, gait disturbance, and seizures. Psychomotor delay was evident from the first months of life. At 17 months, she presented with proximal myoclonic spasms and tonic seizures. After treatment, the patient became seizure free from 5 years. Neurophysiological examinations (including somatosensory evoked potentials and EEG) performed at 3 years were normal. Routine blood and metabolic tests were all within normal range; molecular analyses of UBE3A, MECP2, and FOXG1 genes were negative for mutations. Brain MR at 17 months revealed moderate cortical atrophy, slight DN hyperintensity, and corpus callosum thinning. No basal ganglia iron deposition was present (Fig. 1I,J), but the SN was enlarged (Fig. 1K). At 5 years, she developed ataxic gait, but the parents refused further examinations.

At latest follow‐up at 7 years 8 months, the patient presented with further deterioration of cognition, ataxic gait, hypobradykinetic and hypertonic syndrome, and precocious puberty. A new brain MRI confirmed enlarged SN and prominent bilateral symmetric T2* hypointensity in the GP and, especially, the SN (Fig. 1M,N), together with marked cortical atrophy. On T1w images, a thin dark central band in the bilateral SN, surrounded by a hyperintense peripheral halo (halo sign), was also observed (not shown). Subsequent sequencing of WDR45 showed a novel heterozygous deletion, c.251delA (p.Asp84Alafs*34). Segregation analysis of the mutation was not possible because parental DNA was not available.

Case 4

A 2‐year‐old female was referred to us with psychomotor delay and seizures. After an uneventful pregnancy, the child had presented respiratory distress at birth. MRI at 1 month showed enlarged ventricles, moderate thinning of corpus callosum, swollen SN, and slight DN hyperintensity. Our neurological examination revealed psychomotor delay with absence of language, stereotypic hand movements, and hypotonia/hyper‐reflexia. By 3 years, the epilepsy had worsened: There were prolonged focal seizures and spasms, indicating epileptic encephalopathy. A new MRI at 3 years 9 months showed bilateral symmetric T2* hypointensity in the SN and, to a lesser extent, the ventral GP; at 5 years, a new neurological examination confirmed the presence of psychomotor delay, with poor verbal production but absence of extrapyramidal signs. NBIA was suspected and the patient underwent genetic testing. De novo splicing (c.344 + 1G>A) and missense (c.100G>A (p.Val34Met)) mutations were found on WDR45.

Discussion

BPAN, attributed to WDR45 mutations, is the only known form of NBIA that is X‐linked. Clinical onset is in childhood with early appearance of parkinsonism and dystonia, delayed acquisition of motor and language skills (or regression of acquired functions), and presence of seizures (inconstant), stereotypies (Rett‐like phenotype), sleep disorders, and basal ganglia iron deposition visible on MRI.8, 9 MRI in early childhood is nearly always reported normal, although generalized cerebellar and cerebral atrophy and corpus callosum thinning have occasionally been described.6 As the disease progresses, T2w, but mainly T2* and susceptibility‐weighted imaging sequences, reveal hypointensity as a sign of early‐stage iron deposition.10, 11, 12 Iron accumulates mainly in the SN and, to a lesser extent, in the GP.13, 14 Prominent SN hypointensity is often evident as a thin, dark central band surrounded by a peripheral hyperintense halo (halo sign) on axial T1w images.6

We report on 4 BPAN patients with new WDR45 mutations, in whom retrospective review of the first MRI examination in early childhood—initially reported normal, or at least with cerebral atrophy and corpus callosum thinning—clearly showed an enlarged rounded SN, whereas later scans revealed progressive iron accumulation in the SN and GP bilaterally. To our knowledge, this evolution has not been documented previously in BPAN, and, in particular, early SN swelling has not been reported previously.

The reason for SN swelling is unknown. It is similar in appearance to that observed in olivary pseudohypertrophy, where hypertrophy occurs after interruption of the dentato‐rubro‐olivary tract following a lesion in the triangle of Guillain‐Mollaret: This triggers deafferentation of the inferior olives, initially resulting in neuron and astrocyte enlargement, vacuolation attributed to trans‐synaptic degeneration, and eventually atrophy and cell death.15, 16

The swollen SN in BPAN may also resemble the swelling observed in bilateral striatal necrosi, in which involvement of the neostriatum (putamen and caudate), in acquired or inherited conditions of varying pathogenesis, is characterized by initial swelling followed by atrophy, cell necrosis, and cavitation.17

Neither the deafferentation that occurs in olivary pseudohypertrophy nor the swelling and deflation of the putamen and caudate that occur in bilateral striatal necrosis (both of which result in necrosis and atrophy of the nuclei) can explain the SN swelling of our cases, particularly given that it did not disappear over time. It is possible that early chronic neuroinflammation attributed to dysfunction of the autophagy‐lysosome pathway, followed by gradual iron deposition, account for the swelling.10, 18, 19

Neuroinflammation may evolve rapidly in early SN neurodegeneration as may also occur in early Parkinson's disease and indicated by structural alterations and SN enlargement detected by transcranial B‐mode sonography.20, 21, 22 SN neurodegeneration may also be responsible for extrapyramidal signs5, 23 and, in particular, the parkinsonism present in 2 of our cases.

SN enlargement associated with T2* hypointensity has been described in a few BPAN case reports8 and also in the series reported by Hayflick et al.,6 where these signs were present in MRI performed at advanced disease stage; autopsy in 1 case revealed thinned cerebral peduncles and a gray‐brown SN.

Ishiyama et al.24 recently described 2 children with WDR45 mutations. In both cases MRI during episodes of pyrexia and seizures, at around 2 years, showed unusual transient GP and SN swelling together with T2 hyperintensity. Later, quantitative susceptibility mapping in both cases showed increased magnetic susceptibility in the GP and SN, indicating abnormal iron accumulation.

As regards the bilateral and symmetric DN hyperintensity on T2‐w.i. found in all our cases, this is observed in several other conditions, notably metronidazole‐induced transient DN edema, Canavan's disease, maple syrup urine disease, glutaric aciduria type 1, and Leigh's syndrome. None of these are normally considered in the differential diagnosis of BPAN.25 In our cases, this hyperintensity was clearly evident at first examination, was not progressive, and does not appear to have been reported previously in BPAN. Its presence in association with SN enlargement should induce suspicion of BPAN. Presence of cortical atrophy and corpus callosum thinning (again present in all our patients) should further increase suspicion of BPAN.

SN and GP iron deposition became evident on MRI a relatively short time after initial MR examination, and increased progressively with time—as occurs in other forms of NBIA.6, 26, 27

This evolution, similar to that observed in the GP of PKAN cases,26 suggests that the initial anomalies are attributed to cell damage, whereas the later iron deposition could be secondary to the degenerative process.

Clinical findings in our cases were psychomotor and behavioral signs (progressive cognitive involvement, absence of language, loss of purposeful use of the hands, and stereotypic movements), suggesting Rett syndrome. One patient did not present seizures, and in 2 cases extrapyramidal signs were not present.

Persistently high levels of neuron‐specific enolase in cerebrospinal fluid and serum, and of markers of abnormal myocyte activity (transaminases, creatine kinase, and lactate dehydrogenase) have been described in association with BPAN, and proposed as early signs of the disease.28, 29 These examinations were not performed in our patients.

All except one of the mutations described in our patients are absent from population databases (ExAc, GnomAD, Exome Variant Server, and 1000Genome project) and are to be considered new. The missense mutation in patient 4 has been reported on previously.

All our patients were females, consistent with the known sex distribution of this disease, with only 8 males so far reported on.30

Males seem to have more‐severe phenotypes, or may have more somatic mosaic variants, suggesting that hemizygous mutations are lethal or more severe in males.4, 31 The large number of mutations described, together with the phenomenon of random X‐linked inactivation, could explain much of the phenotypic variability that characterizes BPAN. Further studies on larger samples, which also assess skewed X‐chromosome inactivation, DNA methylation, and environmental factors, are required to better understand this variation.

To conclude, our observations shed new light on the rapid and irreversible SN and GP iron deposition that occurs in BPAN, in that it appears to start from SN swelling in the absence of the iron deposition, which should be considered an early MRI sign of the disease. Early DN T2 hyperintensity was also present in our patients. Cases with a Rett‐like clinical syndrome, possibly without extrapyramidal signs and seizures, and SN swelling on MRI, should be tested for BPAN.

Author Roles

(1) Research Project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Acquisition, Analysis, and Interpretation of Data, D. Study Coordination, E. Genetic Tests; (2) Manuscript Preparation: A. Writing of the First Draft, B. Review and Critique.

C.R.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 1D, 2A

A.A.: 1C, 2B

E.F.: 1C, 2B

S.G.: 1C, 2B

M.M.: 1C, 2B

G.Z.: 1C, 2B

C.P.: 1E

B.C.: 1E

B.G.: 1E

N.N.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 1D, 2A

L.C.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 1D, 2A

Disclosures

Ethical Compliance Statement: All procedures performed on our patients were in accord with the ethical standards of our Institute and the 1964 Helsinki declaration and subsequent amendments. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

Financial Disclosures for previous 12 months: The authors declare that there are no disclosures to report.

Acknowledgments

Informed consent was obtained from all study participants or their parents.

Relevant disclosures and conflicts of interest are listed at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Hogarth P. Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation: diagnosis and management. J Mov Disord 2015;8:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gregory A, Hayflick S. Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation disorders overview In Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., eds. GeneReviews [Internet]. University of Washington, Seattle; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hogarth P, Gregory A, Kruer MC, et al. New NBIA subtype: genetic, clinical, pathologic, and radiographic features of MPAN. Neurology 2013;80:268–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haack TB, Hogarth P, Kruer MC, et al. Exome sequencing reveals de novo WDR45 mutations causing a phenotypically distinct, X‐linked dominant form of NBIA. Am J Hum Genet 2012;91:1144–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhao YG, Sun L, Miao G, et al. The autophagy gene Wdr45/Wipi4 regulates learning and memory function and axonal homeostasis. Autophagy 2015;11:881–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hayflick, SJ , Kruer MC, Gregory A, et al. Beta‐propeller protein‐associated neurodegeneration: a new X‐linked dominant disorder with brain iron accumulation. Brain 2013;136:1708–1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Haack TB, Hogarth P, Gregory A, et al. BPAN: The only X‐linked dominant NBIA disorder. Int Rev Neurobiol 2013;110:85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hattingen E, Handke N, Cremer K, et al. Clinical and imaging presentation of a patient with beta‐propeller protein‐associated neurodegeneration, a rare and sporadic form of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA). Clin Neuroradiol 2017;27:17–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hoffjan S, Ibisler A, Tschentscher A, et al. WDR45 mutations in Rett(‐like) syndrome and developmental delay: case report and an appraisal of the literature. Mol Cell Probes 2016;3D:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liu Z, Shen H, Lian T, et al. Iron deposition in substantia nigra: abnormal iron metabolism, neuroinflammatory mechanism and clinical relevance. Sci Rep 2017;7:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang W, Yan Z, Gao J, et al. Role and mechanism of microglial activation in iron‐induced selective and progressive dopaminergic neurodegeneration. Mol Neurobiol 2016;49:1153–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haacke EM, Xu Y, Cheng YN, Reichenbach R. susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI). Magn Reson Med 2004;52:612–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Langkammer C, Pirpamer L, Seiler S, et al. Quantitative susceptibility mapping in Parkinson's disease. PLoS One 2016;11:e0162460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang J, Li X, Yang R. et al Susceptibility‐weighted imaging manifestations in the brain of Wilson disease patients. PLoS One 2015;10:e0125100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goyal M, Versnick E, Tuite P. Hypertrophic olivary degeneration: meta‐analysis of the temporal evolution of MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2000;21:1073–1077. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goto N, Kakimi S, Kaneko M. Olivary enlargement: stage of initial astrocytic changes. Clin Neuropathol 1988;7:39–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tonduti D, Chiapparini L, Moroni I, et al. Neurological disorders associated with striatal lesions: classification and diagnostic approach. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2016;54:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thomsen MS, Andersen MV, Christoffersen PR, et al. Neurodegeneration with inflammation is accompanied by accumulation of iron and ferritin in microglia and neurons. Neurobiol Dis 2015;81:108–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bodea L, Wang Y, Linnartz‐gerlach B, et al. Neurodegeneration by activation of the microglial complement–phagosome pathway. J Neurosci 2014;34:8546–8556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lerche S, Seppi K, Behnke S, et al. Risk factors and prodromal markers and the development of Parkinson's disease. J Neurol 2014;261:180–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schmidt A, Tunc S, Graf J, et al. A population‐based study on combined markers for early Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2015;30:531–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Berg D and Gaenslen A. Place value of transcranial sonography in early diagnosis of Parkinson's disease. Neurodegener Dis 2010;7:291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Berg D, Postuma RB, Adler CH, Bloem BR. CME MDS research criteria for prodromal Parkinson's disease—key definition features of prodromal PD. Mov Disord 2015;30:1600–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ishiyama A, Kimura Y, Iida A, et al. Transient swelling in the globus pallidus and substantia nigra in childhood suggests SENDA/BPAN. Neurology 2018;90:974–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bond KM, Brinjikji W, Eckel LJ, et al. Dentate update: imaging features of entities that affect the dentate nucleus. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2017;38:1467–1474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chiapparini L, Savoiardo M, D'Arrigo S, et al. The “eye‐of‐the‐tiger” sign may be absent in the early stages of classic pantothenate kinase associated neurodegeneration. Neuropediatrics 2011;42:159–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ward RJ, Zucca FA, Duyn JH, et al. The role of iron in brain ageing and neurodegenerative disorders. Lancet Neurol 2014;13:1045–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Okamoto N, Ikeda T, Hasegawa T, et al. Early manifestations of BPAN in a pediatric patient. Am J Med Genet A 2014;164A:3095–3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Takano K, Shiba N, Wakui K, et al. Elevation of neuron specific enolase and brain iron deposition on susceptibility‐weighted imaging as diagnostic clues for beta‐propeller protein‐associated neurodegeneration in early childhood: additional case report and review of the literature. Am J Med Genet A 2016;170A:322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Carvill GL, Liu A, Mandelstam S, et al. Severe infantile onset developmental and epileptic encephalopathy caused by mutations in autophagy gene WDR45. Epilepsia 2018;59:e5–e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nakashima M, Takano K, Tsuyusaki Y, et al. WDR45 mutations in three male patients with West syndrome. J Hum Genet 2016;61:653–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]