Abstract

Introduction:

In a previous report, we used latent class analysis (LCA) to identify natural subgroups of older adults in the Einstein Aging Study (EAS) based on neuropsychological performance. These subgroups differed in demographics, genetic profile and prognosis. Herein, we assess the generalizability of these findings to an independent sample, the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP), which used an overlapping, but distinct neuropsychological battery.

Aims:

Our aim was to identify the association of natural subgroups based on neuropsychological performance in the MAP cohort with incident dementia and compare them with the associations identified in the EAS.

Methods:

MAP is a community-dwelling cohort of older adults living in the northeastern Illinois, Chicago. Latent class models were applied to baseline scores of 10 neuropsychological measures across 1,662 dementia-free MAP participants. Results were compared to prior findings from the EAS.

Results:

LCA resulted in a 5-class model: Mixed-Domain Impairment (n = 71, 4.3%), Memory-specific-Impairment (n = 274, 16.5%), Average (n = 767, 46.1%), Frontal Impairment (n = 222, 13.4%), and a class of Superior Cognition (n = 328, 19.7%). Similar to the EAS, the Mixed-Domain Impairment, the Memory-Specific Impairment, and the Frontal Impairment classes had higher risk of incident Alzheimer’s dementia when compared to the Average class. By contrast, the Superior Cognition had a lower risk of Alzheimer’s dementia when compared to the Average class.

Conclusions:

Natural cognitive subgroups in MAP are similar to those identified in EAS. These similarities, despite study differences in geography, sampling strategy, and cognitive tests, suggest that LCA is capable of identifying classes that are not limited to a single sample or a set of cognitive tests.

Keywords: Neuropsychological profiles, latent class analysis, Alzheimer’s dementia, dementia

Introduction

Identifying dementia-related heterogeneity at a preclinical stage would facilitate early diagnosis, improve clinical trials by targeting high-risk populations, and ultimately help in finding effective treatment before irreversible neurodegeneration. Previous studies have identified heterogeneity in populations based on neuropsychological tests in different cohorts [1–5]. To assess the generalizability, it is necessary to show that subgroups identified in independent samples are comparable.

In a previous study (in revision), we applied latent class analysis (LCA) to the Einstein Aging Study (EAS) and identified 5 clinically-meaningful classes based on neuropsychological performance. We showed that these natural subgroups differed in a number of variables, which were not used to define the classes, including demographics, distribution of genotypes, and clinical outcomes. The five classes we identified were: Mixed-Domains Impairment, Memory-Specific Impairment, Frontal Impairment, Average, and Superior Cognition. While the incidence of dementia was low for the “Average” and “Superior Cognition” classes, the “Mixed-Domain Impairment” and the “Memory-Specific Impairment” classes had an increased incidence of all-cause dementia and Alzheimer’s dementia within the first 4 years of follow-up. In contrast, the “Frontal Impairment” class showed an increase in the risk of dementia between 4 and 8 years of follow-up. Since this study was limited to the EAS sample, we were not able to make a definitive conclusion regarding the replicability of our findings, and whether the identified natural subgroups of older adults were replicable in a separate cohort and cognitive battery.

In the current study, we aimed to fit latent class analyses on a sample from the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP) to identify homogenous subgroups and to evaluate whether the identified classes resemble those in the EAS and exhibit similar associations with incident dementia. MAP is a well-established community-based cohort of older adults, and like the EAS, has an extensive neuropsychological battery representing five cognitive domains of episodic memory, semantic memory, working memory, perceptual orientation, and perceptual speed. Identifying homogeneous cognitive patterns with similarities across these 2 cohorts is an important step toward finding replicable natural subgroups.

Methods

2.1. Participants.

A detailed description of the MAP study designs has been previously reported [6]. Briefly, study participants were community-dwelling older adults from about 40 retirement communities and senior subsidized housing facilities across northeastern Illinois, Chicago. Participants were older, free of known dementia at baseline, agreed to annual clinical evaluation, and signed an informed consent and an Anatomical Gift Act for brain donation at the time of death. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Rush University Medical Center. Annual clinical evaluation included detailed neuropsychological testing, a medical history, and physical examination.

2.2. Procedure.

For the purpose of this study, we aimed to follow similar methods to what was used for the EAS sample in our previous study. Therefore, participants who had at least one follow-up wave, and were dementia-free at baseline, were included in this study. Furthermore, we selected neuropsychological tests that were analogous to both studies.

Of the 1,924 MAP participants at the time of these analyses, 79 individuals were excluded due to diagnosis of dementia at baseline and 183 were excluded as they did not have any follow-up visit due to enrollment within the prior year, death, or dropout. A total of 1,662 individuals were included in these analyses. We selected neuropsychological tests from MAP that overlapped with, or measured the same domains as, the EAS neuropsychological battery. Using similar methods and a similar neuropsychological battery helps with determining whether comparable heterogeneity exists between the two cohorts. We selected ten neuropsychological tests within five different cognitive domains (two tests per domain of episodic memory, semantic memory, working memory, perceptual orientation, and perceptual speed) that corresponded to the domains used for the EAS sample. In addition, covariates of age, sex, and education were included in LCA models.

2.2.1. Neuropsychological battery.

The following neuropsychological tests were selected for each domain:

Episodic memory – Logical Memory and the CERAD Word List Recall;

Semantic memory – Boston Naming Test and Category fluency;

Working memory – Digits (sum) and Digit Ordering;

Perceptual Orientation – Matrices and Line Orientation;

Perceptual Speed – Symbol Digits Modalities Test and Number Composition.

The neuropsychological measures in the EAS were similar. Supplementary Table 1 shows the complete list.

2.2.2. External validators.

We used two main sources of external measures: genetics, specifically APOE ε4; and vascular risk, specifically use of hypertensive medication, lipid lowering medication, history of diabetes, and an index of cumulative vascular disease (i.e. history of claudication, stroke, myocardial infarction, or heart conditions). Participants supplied all medications prescribed by a doctor taken in the 2 weeks prior to the evaluation. Direct visual inspection of all containers of prescription and over-the-counter agents allowed for medication documentation. Medications were subsequently coded using the Medi-Span Drug Data Base system. History of disease was based on self-reports.

APOE data were generated by Polymorphic DNA Technologies: http://www.polymorphicdna.com/ [9].

We also investigated global cognitive status using the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) [10] and lexical knowledge using the National Adult Reading Test (NART)[11].

Dementia Diagnosis.

Diagnostic classification of Alzheimer’s and other dementias in MAP were made using a three-step process that includes algorithms and clinical judgment as described previously [12–14]. A dementia diagnosis required meaningful decline in cognitive function in addition to impairment in multiple areas of cognition. Alzheimer’s dementia required presence of dementia and loss of episodic memory based on criteria by the National Institute of Neurologic and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the AD and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) [15]. This was further diagnosed as the presence or absence, probable or possible Alzheimer’s dementia.

2.3. Statistical analysis.

2.3.1. Latent Class Analysis.

We fitted LCA models to 10 neuropsychological variables and 3 demographic covariates (age, sex, and education) with classes ranging between 2 and 6 classes. We applied 500 random starts in the initial stage and 10 optimizations in the final stage for appropriate model convergence. The optimal model was chosen based on the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) [16] an index that combines model fit and parsimony. Models with lower BIC indicate better fit. Class separation was evaluated using entropy values, an index that ranges between 0–1 with higher values indicating better separation [17].

2.3.2. Assessment of differences between different classes.

Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) was used for continuous variables, and Chi-square tests were used for categorical variables. We used Cox proportional hazards regression models to determine the adjusted hazard ratio of incident probable AD, possible AD, and non-AD dementia. Since age, sex, and education were already taken into account in defining the classes, no further adjustments were made in the models. The Average class was the reference group.

For LCA modeling we used MPlus version 8 [18]. SPSS, version 24 [19], was used for all other analyses.

Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

The average age of the sample was 79.6 (SD = 7.4) years, 75.4% were female, and 93.4% were non-Hispanic white. The average number of years of education was 14.8 (SD = 3.2) years, with an average of 7.9 points (SD = 2.3) on the NART. Table 1 shows detailed information on demographics, genetics, vascular risk, and neuropsychological performance of the whole sample. Supplementary Table 2 shows basic demographic characteristics of the EAS and the MAP.

Table 1.

Demographic and neuropsychological characteristics of the Memory and Aging Project cohort at baseline.

| Characteristics | Whole sample |

|---|---|

| N (%) | 1,662 (100%) |

| Demographics | |

| Age, years (SD) | 79.6 (7.4) |

| Females (%) | 1,253 (75.4) |

| Education, years (SD) | 14.8 (3.2) |

| NART (SD) | 7.9 (2.3) |

| MMSE (SD) | 28.0 (2.0) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1,550 (93.4) |

| African American | 94 (5.7) |

| Other | 16 (0.9) |

| Genetics | |

| APOE e4 | 334 (23.5) |

| APOE e4e4 | 20 (1.4) |

| Neuropsychological Performance | |

| Word List Recall (SD) | 5.3 (2.4) |

| Logical Memory (SD) | 11.0 (4.3) |

| Boston Naming Task (SD) | 13.9 (1.3) |

| Categories (SD) | 34.1 (9.0) |

| Digits Sum (SD) | 8.3 (2.0) |

| Progressive Matrices (SD) | 11.7 (2.8) |

| Line Orientation (SD) | 10.0 (3.1) |

| Symbol Digits Modalities Test (SD) | 38.2 (10.6) |

| Number Comparison (SD) | 24.4 (7.4) |

| Vascular Risk | |

| Hypertension medication (%) | 868 (52.2) |

| Lipid Lowering Medication (%) | 623 (37.5) |

| Diabetes (%) | 214 (12.9) |

| Cumulative vascular risks (%) | 1,244 (74.8) |

| Cumulative vascular disease (%) | 338 (20.3) |

3.2. Latent Class Analysis

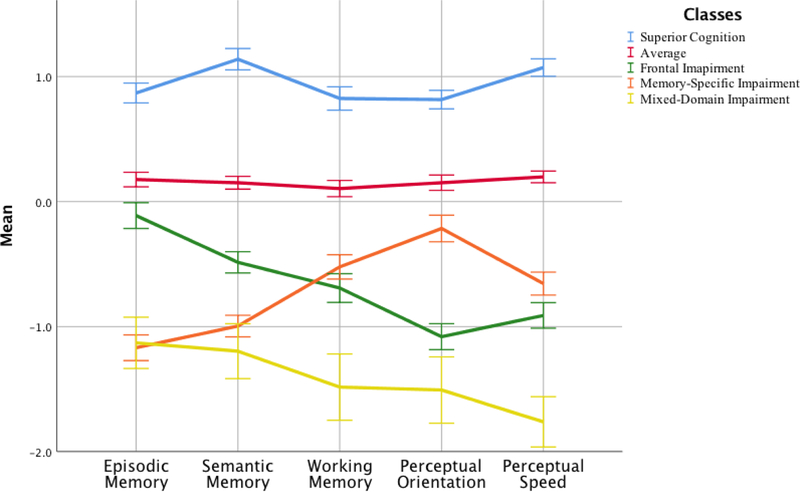

Models were fit for 2- to 6-class solutions. Although the values of the BIC kept improving with every added class, the entropy varied between 0.75 for the 6-class solution to 0.82 for the 2-class solution. Since the average posterior probabilities of group membership for individuals assigned to each group exceeded a minimum threshold of 0.7 [20], and the BIC kept improving [16] , we looked into some more details of the solutions such as % of the smallest class and classification accuracy. Supplementary Table 3 shows model-fit statistic details for all classes. While the 4-class solution had slightly higher entropy than both the 3-class model (0.80 vs 0.78) and the 5-class model (0.80 vs. 0.79), the pattern of scores in the 4-class model were quantitative, and no meaningful classes were extracted. Both the 5-class and the 4-class models had one class as small as 4% of the cohort. When adding a 6th class the entropy dropped substantially (from 0.79 to 0.75) as well as the % of the smallest class. Considering these results and that LCA models in the EAS led to an optimal 5-class solution, we decided to investigate further the 5-class solution. Results showed a similar pattern across cognitive domains as we found in the EAS. Specifically, reflecting EAS class profiles a superior cognition class, an average class, and a mixed-domains impairment class emerged; the two other classes showed dissociations, with one class performing better on tasks of frontal-executive measures and worse on measures of episodic memory, and vice-versa, hence the frontal impairment class and the memory-specific class. We thus decided to explore this model further.

Table 2 shows the demographic and neuropsychological characteristics of each of the classes. The Mixed-Domains Impairment (n = 71, 4.3%) had poor scores on all neuropsychological measures when compared to the rest of the classes. The Memory-Specific Impairment class (n = 274, 16.7%) had the poorest scores on tests of episodic memory (Word List Recall and Logical Memory); it also had poor scores on tests of semantic memory (Boston Naming Task and Categories) relative to the rest of the classes. Compared to the rest of the classes the Frontal Impairment class (n = 222; 13.4%) had low scores on domains on perceptual reasoning (Number Comparison and Symbol Digits Modalities Test) and perceptual orientation (Line Orientation and Progressive Matrices). The Average (n = 222, 13.4%) and Superior Cognition (n = 328, 19.7%) class had better performance compared to the rest of the classes on all measures of neuropsychological function. Supplementary Table 4 compares the class composition between the EAS and the MAP.

Table 2.

Demographic and neuropsychological characteristics of the Memory and Aging Project cohort at baseline.

| Cognitive Performance | Mixed-Domain Impairment | Memory-Specific Impairment | Average | Frontal Impairment | Superior Cognition | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 71 (4.3%) | N = 274 (16.5%) | N = 767 (46.1%) | 222 (13.4%) | 328 (19.7%) | ||

| Demographics | ||||||

| 1Age, years (SD) | 79.5 (9.3) | 84.5 (5.4) | 80.2 (6.4) | 79.7 (7.6) | 73.8 (7.0) | <0.001 |

| 1Females (%) | 58 (81.7) | 153 (55.8) | 597 (77.8) | 198 (89.2) | 247 (75.3) | <0.001 |

| White | 56 (78.9) | 266 (97.1) | 726 (94.9) | 188 (84.7) | 314 (95.7) | <0.001 |

| African American | 12 (16.9) | 6 (2.2) | 32 (4.2) | 31 (14.0) | 13 (4.0) | |

| Other | 3 (4.2) | 2 (0.7) | 7 (0.9) | 3 (1.3) | 1 (0.3) | |

| 1Education (SD) | 10.9 (3.8) | 14.4 (2.9) | 15.0 (2.6) | 12.5 (2.6) | 16.7 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| NART (SD) | 4.2 (3.1) | 7.6 (2.4) | 8.3 (1.9) | 6.6 (2.7) | 9.0 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| MMSE | 24.6 (2.8) | 26.5 (2.3) | 28.5 (1.3) | 27.4 (1.9) | 29.2 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| Genetics | ||||||

| APOE e4 | 22 (34.9) | 71 (29.6) | 140 (21.4) | 36 (18.0) | 65 (24.4) | <0.01 |

| APOE e4e4 | 2 (3.2) | 2 (0.8) | 8 (1.2) | 5 (2.5) | 3 (1.1) | 0.01 |

| Neuropsychological Performance | ||||||

| Episodic Memory | ||||||

| Word List Recall (SD) | 2.36 (2.0) | 2.2 (1.6) | 5.8 (1.8) | 5.4 (1.6) | 7.3 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| Logical Memory (SD) | 11.1 (6.6) | 11.0 (6.2) | 21.5 (6.8) | 19.1 (6.5) | 27.8 (6.4) | <0.001 |

| Semantic Memory | ||||||

| Boston Naming Task (SD) | 10.5 (2.2) | 13.3 (1.2) | 14.2 (0.9) | 13.4 (1.2) | 14.6 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Categories (SD) | 23.4 (7.2) | 25.3 (5.8) | 35.2 (6.2) | 29.5 (5.9) | 44.2 (7.3) | <0.001 |

| Working Memory | ||||||

| Digits Sum (SD) | 11.2 (3.1) | 13.1 (2.8) | 14.8 (3.3) | 12.1 (3.1) | 16.9 (3.1) | <0.001 |

| Ordering (SD) | 4.2 (2.1) | 6.3 (1.2) | 7.4 (1.3) | 6.5 (1.2) | 8.4 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| Perceptual Reasoning | ||||||

| Number Comparison (SD) | 13.1 (7.1) | 20.8 (5.8) | 25.7 (5.6) | 18.8 (6.2) | 30.7 (5.7) | <0.001 |

| Symbol Digits Modalities Test (SD) | 18.7 (8.3) | 30.5 (7.6) | 40.3 (6.6) | 28.6 (8.0) | 49.5 (6.4) | <0.001 |

| Perceptual Orientation | ||||||

| Line Orientation (SD) | 6.4 (3.5) | 9.8 (3.0) | 10.3 (2.7) | 7.8 (2.8) | 11.7 (2.5) | <0.001 |

| Progressive Matrices (SD) | 7.8 (2.5) | 11.0 (2.2) | 12.2 (2.2) | 8.7 (2.6) | 14.1 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| Vascular Risk | ||||||

| Hypertension medication (%) | 49 (69) | 132 (48.2) | 127 (57.2) | 418 (54.5) | 142 (43.4) | <0.001 |

| Lipid Lowering Medication (%) | 25 (35.2) | 103 (37.6) | 81 (36.5) | 283 (36.9) | 131 (39.9) | 0.877 |

| Diabetes (%) | 18 (25.4) | 24 (8.8) | 45 (20.3) | 89 (11.6) | 38 (11.6) | <0.001 |

| 2Cumulative vascular disease (%) | 17 (23.9) | 73 (26.6) | 56 (25.2) | 153 (19.9) | 39 (11.9) | <0.001 |

Note.

Indicates variables that were used as covariates in the latent class model. NART = National Adult Reading Test.

Cumulative Vascular Disease = history of either claudication, stroke, myocardial infarction, or heart conditions.

Figure 1 displays the pattern of neuropsychological scores of the classes using summary domains of episodic memory, semantic memory, working memory, perceptual speed, and perceptual orientation. Supplementary Figure 1 shows the EAS generated pattern of scores across similar domains of cognitive function: Episodic memory, semantic/language fluency, visual and spatial function, attention/working memory, and executive function.

Figure 1.

Figure illustrating how each of the classes performed on neuropsychological measures reflecting domains of episodic memory, semantic memory, working memory, perceptual orientation, and perceptual speed.

3.3. Vascular Risk and APOEε4

Statistical analysis revealed that there were differences amongst the classes in terms of hypertension-medication use, diabetes, and cumulative vascular disease. The Mixed-Domains Impairment class had the highest proportions of individuals with diabetes and on hypertensive medication (25.4% and 69%), while the Memory-Specific Impairment class had the highest proportion of individuals with vascular disease (25.2%).

Within the Mixed-Domains Impairment class and the Memory-Specific Class 34.9% and 29.6% had APOE ε4, while in the Frontal Impairment classes only 18% had APOEε4. Up to 3.2% and 2.5% of individuals in the Mixed-Domains Impairment and the Frontal Impairment classes had the ε4/ε4 allele.

3.4. Clinical Outcomes

The median years of follow-up was 5.1 years (SD = 4.1); these ranged from 3.1 years (SD = 2.1) in the Mixed-Domain Class to 6.9 years (SD = 4.5) in the Superior Cognition class. The average time to first diagnosis of dementia was 5.4 years (SD = 3.7); this ranged from 3.3 years (SD = 2.5) in the Mixed-Domain Class to 10.1 years (SD = 4.0) in the Superior Cognition Class.

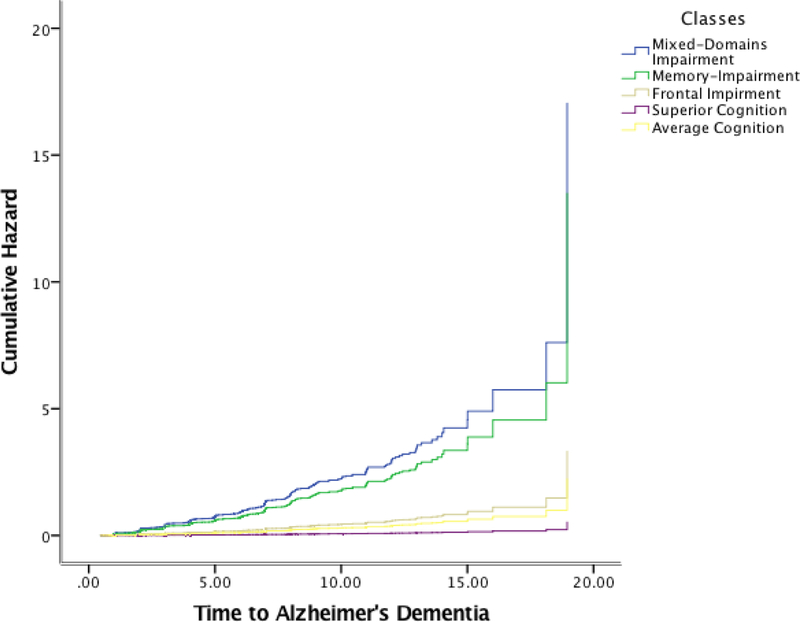

There were 349 cases of incident dementia, 330 of which were Alzheimer’s type (Table 3). Incidence per 100 person-years for dementia ranged from 15 in the Mixed-Domains class to 0.7 in the Superior Cognition class; for AD this ranged from 13.7 in the Mixed-Domains class to 0.6 in the Superior class. Incidence rates for dementia and AD were lower across all classes in the EAS; these ranged from 0.5 in the Superior Cognition Class to 8.6 in the Mixed-Domain Impairment Class for dementia, and from 0.3 to 7.0 for AD.

Table 3.

Incidence rates of all-cause dementia and Alzheimer’s dementia per 100 years stratified by the five generated classes.

| N (%) | Person-years | Dementia cases (%) |

Incidence-rate per 100 person-years |

AD* cases (%) |

Incidence-rate per 100 person-years |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed-Domain Impairment | 71 (4.3) | 219.4 | 33 (9.5) | 15.0 | 30 (9.1) | 13.7 |

| Memory-Specific Impairment | 274 (16.5) | 1076.0 | 124 (35.5) | 11.5 | 121 (36.7) | 11.2 |

| Frontal Impairment | 222 (13.4) | 1271.8 | 47 (13.5) | 3.7 | 43 (13.0) | 3.4 |

| Average | 767 (46.1) | 4993.1 | 129 (37.1) | 2.6 | 121 (36.7) | 2.4 |

| Superior Cognition | 328 (19.7) | 2431.0 | 16 (4.6) | 0.7 | 15 (4.5) | 0.6 |

| Total | 1,662 (100) | 9991.3 | 349 (100) | 3.5 | 330 (100) | 3.3 |

Note. AD = Alzheimer’s Dementia.

includes both possible and probable AD

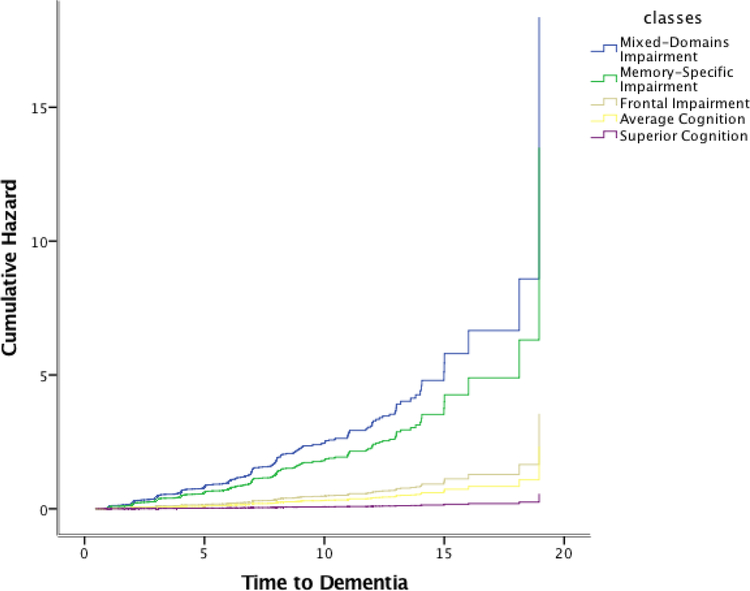

Cox proportional hazards models for incident AD and for incident dementia with the classes as independent predictors and the Average class as reference, showed that the Mixed-Domain Impairment, the Memory-Specific Impairment, and the Frontal Impairment class were associated with elevated risk of incident AD (HR = 8.4, 95%CI = 5.6 – 12.6; HR = 6.1, 95%CI = 4.7 – 8.1; HR = 1.6, 95% CI = 1.1 – 2.3) and dementia (HR = 7.9, 95%CI = 5.4 – 11.7; HR = 5.8, 4.5 – 7.5; HR = 1.5, 95%CI = 1.1 – 2.1). Figures 2 and 3 display the cumulative hazard rates of each of the classes for dementia and for AD.

Figure 2.

Cumulative Hazards of Dementia for each of the classes.

Figure 3.

Cumulative hazards of Alzheimer’s dementia for each of the classes.

The proportional hazards assumption was met overall, thus we proceeded in stratifying the models into specific time intervals. When stratified into time intervals, the Mixed Domains Impairment Class, the Memory Specific Class, and the Frontal Impairment class were associated with a higher risk of incident Alzheimer’s dementia and non-AD dementia when compared to the Average class (Table 4). The Memory Specific class continued to be at elevated risk even between 4 and 8 years of follow-up; but the rest of the classes did not. The Superior Cognition Class was associated with a lower risk of incident AD and non-AD dementia (Table 4).

Table 4.

Hazards ratios of incidence of Alzheimer’s dementia and non-AD dementia until end of follow-up and stratified into 4-year intervals.

| Mixed-Domain Impairment | Memory-Specific Impairment | Average | Frontal Impairment | Superior Cognition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | HR (95%CI) | HR (95%CI) | HR (95%CI) | HR (95%CI) | |

| Alzheimer’s Dementia |

7.7 (5.1 – 11.5)*** | 6.1 (4.7 – 7.9)*** | Ref. | 1.5 (1.1 – 2.1)* | 0.2 (0.1 – 0.4) |

| <4 | 7.6 (4.4 – 13.1)*** | 5.0 (3.2 – 7.9)*** | Ref. | 2.0 (1.1 – 3.6)* | 0.1 (0.02 – 1.0)* |

| 4 −8 | 0.6 (0.1 – 4.5) | 3.2 (2.1 – 4.9)*** | Ref. | 1.2 (0.7 – 2.3) | 0.3 (0.2 – 0.8)** |

| ≥8 | 3.1 (1.0 – 10.1)* | 1.5 (0.6 – 3.8) | Ref. | 1.2 (0.6 – 2.2) | 0.2 (0.9 – 0.5)*** |

| Non-AD dementia | 7.9 (5.4 – 11.7)*** | 5.8 (4.5 – 7.5)*** | Ref. | 1.5 (1.1 – 2.1)* | 0.2 (0.1 – 0.4)*** |

| <4 | 7.6 (4.5 – 12.7)*** | 4.6 (3.0 – 7.1)*** | Ref. | 1.8 (1.0 – 3.3)* | 0.1 (0.01 – 0.9)* |

| 4 −8 | 0.6 (0.8 – 4.3) | 3.1 (2.0 – 4.6)*** | Ref. | 1.5 (0.8 – 2.6) | 0.4 (0.2 – 0.8)* |

| ≥8 | 3.0 (0.9 – 9.8)^ | 1.7 (0.7 – 4.1) | Ref. | 1.1 (0.6 – 2.1) | 0.2 (0.1 – 0.4)*** |

Discussion

In this study we extended our work on the EAS cohort to the MAP cohort. We compared natural subgroups across the two studies to see if results from the MAP resembled those found in EAS. We selected neuropsychological tests with the highest overlap with the EAS, which measured the same cognitive domains. Our results showed that LCA based on the neuropsychological performance identifies similar natural subgroups in both MAP and EAS. These data show that the LCA models provide replicable results.

In comparison to the EAS, this sample was slightly older, had higher levels of education, and higher MMSE score at baseline. In MAP, the percentage of females and whites was higher, which indicates less diversity than the EAS. Like the EAS, a 5-class solution characterized the MAP cohort with one class relating to individuals who performed poorly on all neuropsychological measures (the Mixed Domains Impairment class), another class containing individuals who performed poorly on episodic memory measures (the Memory Specific Impairment class), a third class with individuals who performed poorly on just tests of frontal executive function (the Frontal Impairment class), and another two classes with individuals who scored average relative to the rest (the Average Class), and with individuals who showed superior performance (the Superior Cognition class). Like the EAS, the biggest class in MAP was the Average class (40.1% in EAS and 46.1% in MAP), which was expected given that the samples consist of community-dwelling participants. Compared to the five-class model in the EAS, there were more individuals in the Superior Cognition and Average classes (19.7% vs. 9.2% and 46.1% vs. 40.1%) and less in the Mixed Domain Impairment Class (4.3% vs 8%) and the Memory Specific Class (16.5% vs. 34%) in MAP. A higher proportion of participants in MAP belonged to the Frontal Impairment class than in the EAS (13.4% vs. 8.8%).

We also examined vascular risk across classes, and similar to the EAS, results showed that classes with poorer cognitive performance also had a worse vascular profile. Specifically, MAP classes also varied from negligible risk to high risk of incident AD and non-AD dementia, over a mean of six years of follow-up. The Mixed-Domains Impairment class showed the highest hazards ratio, while the Frontal Impairment Class showed the lowest. While in EAS both the Mixed-Domains and Memory-Specific classes were at higher risks of incident dementia in the first four years of follow-up than later time-intervals, in MAP the Memory-Specific class showed higher risk of incident dementia after the first four years. This may be because in the MAP cohort there is more AD-related dementia than in the EAS. In fact, in this cohort the vast majority of the cases are AD and mixed-AD [21, 22]. Further, while the Frontal Impairment Class was only associated with higher risk of incident dementia between 4 and 8 years of follow-up in EAS, this was not the case in MAP, where higher risk was associated within the first four years of follow-up, but not between 4 and 8 years from enrollment, which again may imply power issues for non-AD dementia in the MAP cohort.

Although replication of latent class characteristics in two independent community-based samples of older adults is reassuring, especially since both studies have very different recruiting methods (the EAS only enrolls community-dwelling individuals, while MAP only enrolls individuals from senior subsidized housing and retirement homes) further assessment in other cohorts is recommended. Replication studies in research add trust, confidence, and validity to the results and to the underlying theory. Replication studies should be conceptualized as a process of conducting a series of studies that are open to alternative explanations and real-world relevance [23]. Although, replication of longitudinal research is challenging due to differences in birth cohort, age range, culture and education of participants, differences in study design and differences in neuropsychological test selection, part of the new NIH requirements include rigor and reproducibility of research [23]. Longitudinal research with long follow-up is necessary to elucidate accurately the within-individual progression of cognitive trajectories and their resultant clinical outcomes. This knowledge is crucial as increasing efforts are directed towards primary prevention trials in preclinical AD, with accurate profiles of individuals for trial enrolment and to monitor treatment response in the absence of clinical symptoms. Identification and verification of trajectory profiles will ultimately inform on recommendations for more precise targeting of individuals suitable for clinical trials aiming at preventing and/or treating MCI and dementia.

Limitations and future directions.

Some limitations are inherent in cohort studies, and relate to different recruitment strategies across cohorts (which may lead to somewhat different results, e.g. dementia incidence rates are lower in the EAS possibly because the sample is initially healthier than MAP because participants are only eligible if they are community-dwelling, whereas the opposite holds for MAP), different means of establishing a diagnosis (annual conference case diagnosis in EAS vs. a computerized algorithm in MAP), and even inherent demographic qualities of the participants themselves, such as level of education. These specific idiosyncrasies across cohorts makes replication criteria harder to meet; however, in light of these cohort-characteristic differences yet similar latent profiles across studies, makes results from the latent class models stronger.

We stratified time-to-event in four-year time periods to have the study comparable to the EAS. However, compared to the Mixed-Domains Impairment and the Memory-Specific Impairment Classes, the other classes had a longer than average length of follow-up (>4 years), which makes this time-frame a limitation, especially since the Mixed-Domains Impairment class only has an average of 3.1 years of follow-up.

Although our results indicate substantial similarities between MAP and EAS, in the current study, we only used neuropsychological tests that belonged to the same domains available in the EAS. In separate analyses (available on request) we applied several different models: One model utilized the whole MAP battery, which includes 19 neuropsychological tests, another utilized the five defined domains (episodic memory, semantic memory, working memory, perceptual orientation, and perceptual speed) in MAP, and another model divided the MAP-defined global domain into quintiles. While the two latter models that utilized the domains displayed only quantitative differences amongst the groups, the model which incorporated all 19 measures provided a different pattern of cognitive scores across classes. Our explanation to these differences is that the latent class model is indicator-dependent, meaning that if you put in different indicators, you will get different results. Robustness was achieved on the sample when using similar measures, but not when adding on measures that were not used in the original model. Furthermore, in terms of group assignment, external validity, and predictive validity, the models were robust across both the EAS and MAP. In summary, if similar neuropsychological measures were applied, similar classes were identified, but if different measures were applied, or if domains were used instead, the model identified different patterns. This leaves us with some unanswered questions as to whether the classes are robust, if they are meaningful, and most importantly, whether they are useful. It also possibly tells us that we have not yet discovered the purest and most homogeneous classes. Further research is needed to replicate these findings across different cohorts using different neuropsychological batteries.

In future work we plan to link these classes to clinical diagnoses proximate to death and neuropathologic indices as further external validation. We also plan on adding mortality as a competing risk to dementia within the classes. Furthermore, we plan on applying confirmatory LCA, which aims are to set in motion theoretical advancement and to formalize replication and validation efforts [24]. Differences in birth cohort, age range, ethnicity, health disparities, culture and education of participants, and differences in study design, including choice of covariates and frequency of follow-up make longitudinal studies hard to replicate.

However, in future studies we will incorporate these results into a coordinated analysis in an effort to harmonize datasets that are part of a bigger network [25, 26]. This will help in identifying homogeneous neuropsychological profiles and compare results across datasets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We thank the EAS research participants. We thank Charlotte Magnotta, Diane Sparracio and April Russo for assistance in participant recruitment; Betty Forro, Wendy Ramratan, and Mary Joan Sebastian for assistance in clinical and neuropsychological assessments; Michael Potenza for assistance in data management.

Funding sources: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute On Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K01AG054700; by the Einstein Aging Study (PO1 AG03949) from the National Institutes on Aging program; the National Institutes of Health CTSA (1UL1TR001073) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), the Sylvia and Leonard Marx Foundation, and the Czap Foundation. The Memory and Aging Project was supported by grant R01AG17917 from the National Institute on Aging. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: All authors declare that there are no financial, personal, or other potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bondi MW, et al. , Neuropsychological criteria for mild cognitive impairment improves diagnostic precision, biomarker associations, and progression rates. J Alzheimers Dis, 2014. 42(1): p. 275–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark LR, et al. , Are empirically-derived subtypes of mild cognitive impairment consistent with conventional subtypes? J Int Neuropsychol Soc, 2013. 19(6): p. 635–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delano-Wood L, et al. , Heterogeneity in mild cognitive impairment: Differences in neuropsychological profile and associated white matter lesion pathology. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society : JINS, 2009. 15(6): p. 906–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zammit AR, et al. , Identification of Heterogeneous Cognitive Subgroups in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Latent Class Analysis of the Einstein Aging Study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc, 2018: p. 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Zahodne LB, et al. , Late-life memory trajectories in relation to incident dementia and regional brain atrophy. J Neurol, 2015. 262(11): p. 2484–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett DA, et al. , Religious Orders Study and Rush Memory and Aging Project. J Alzheimers Dis, 2018. 64(s1): p. S161–s189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buschke H, Cued recall in amnesia. J Clin Neuropsychol, 1984. 6(4): p. 433–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaplan E, et al. , Boston naming test 1983, Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu L, et al. , Neuropathologic features of TOMM40 ‘523 variant on late-life cognitive decline. Alzheimers Dement, 2017. 13(12): p. 1380–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Folstein MF, Robins LN, and Helzer JE, The mini-mental state examination. Archives of General Psychiatry, 1983. 40(7): p. 812–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson RS, et al. , Loss of basic lexical knowledge in old age. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 2011. 82(4): p. 369–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett DA, et al. , Overview and findings from the religious orders study. Curr Alzheimer Res, 2012. 9(6): p. 628–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bennett DA, et al. , Overview and findings from the rush Memory and Aging Project. Curr Alzheimer Res, 2012. 9(6): p. 646–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett DA, et al. , Natural history of mild cognitive impairment in older persons. Neurology, 2002. 59(2): p. 198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKhann GM, et al. , The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement, 2011. 7(3): p. 263–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raftery AE, Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociological methodology, 1995: p. 111–163.

- 17.Celeux G and Soromenho G, An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. Journal of Classification, 1996. 13(2): p. 195–212. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muthén LK and Muthén BO, MPlus User’s Guide 1998–2016, Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 19.SPSS Inc., IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows Released 2016, IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagin DS and Odgers CL, Group-Based Trajectory Modeling (Nearly) Two Decades Later. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 2010. 26(4): p. 445–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneider JA, et al. , The neuropathology of probable Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol, 2009. 66(2): p. 200–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bennett DA, et al. , Overview and Findings from the Rush Memory and Aging Project. Current Alzheimer research, 2012. 9(6): p. 646–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hüffmeier J, Mazei J, and Schultze T, Reconceptualizing replication as a sequence of different studies: A replication typology. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2016. 66: p. 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmiege SJ, Masyn KE, and Bryan AD, Confirmatory Latent Class Analysis: Illustrations of Empirically Driven and Theoretically Driven Model Constraints. Organizational Research Methods, 2017: p. 1094428117747689.

- 25.Hofer SM and Piccinin AM, Integrative data analysis through coordination of measurement and analysis protocol across independent longitudinal studies. Psychol Methods, 2009. 14(2): p. 150–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hofer SM and Piccinin AM, Toward an integrative science of life-span development and aging. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 2010. 65B(3): p. 269–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.