Abstract

Interactions of ribonucleic acids (RNA) with basic ligands such as proteins or aminoglycosides play a key role in fundamental biological processes. Native top-down mass spectrometry (MS) has recently been extended to binding site mapping of RNA–ligand interactions by collisionally activated dissociation, without the need for laborious sample preparation procedures. The technique relies on the preservation of noncovalent interactions at energies that are sufficiently high to cause RNA backbone cleavage. In this study, we address the question of how many and what types of noncovalent interactions allow for binding site mapping by top-down MS. We show that proton transfer from protonated ligand to deprotonated RNA within salt bridges initiates loss of the ligand, but that proton transfer becomes energetically unfavorable in the presence of additional hydrogen bonds such that the noncovalent interactions remain stronger than the covalent RNA backbone bonds.

Native mass spectrometry (MS) is an evolving technique1−3 for the study of biomolecular complexes that relies on the retention of noncovalent interactions during and after solvent removal by electrospray ionization (ESI). If, to what extent, and on what time scale biomolecular structure can be preserved after transfer into the gas phase has become an active field of research.4−8 Solvent removal on its own can cause structural changes as it alters the strength of noncovalent interactions,4 and native “top-down” MS approaches9−18 employ various dissociation techniques by which the energy of the biomolecular complexes is increased. The kind of information that can be obtained in native top-down MS experiments thus critically depends on the relative stability of noncovalent interactions and covalent bonds: If the latter are more stable, complex composition and stoichiometry can be revealed, whereas if the former are more stable, binding sites and primary structure can be determined.3 The cleavage of covalent bonds while preserving noncovalent interactions seems counterintuitive, especially when slow heating methods such as collisionally activated dissociation (CAD) are used. Nevertheless, a number of gas-phase studies have demonstrated that noncovalent bonds can be stronger than covalent bonds.10,18−22

For example, we have recently shown that the electrostatic interactions between TAR ribonucleic acid (RNA) and a peptide comprising the arginine-rich binding region of tat protein are sufficiently strong in the gas phase to survive RNA backbone bond cleavage by CAD, thus allowing its use for probing tat binding sites in TAR RNA.10 X-ray crystallography23 and solution NMR24 were so far unsuccessful in providing a detailed picture of the TAR–tat binding interface, but highly converging structures of TAR RNA in a complex with a cyclic tat peptide mimetic showed interactions of all basic residues with phosphodiester moieties25 and excellent agreement with the binding site predicted from our MS data.10 At the solution pH of 7.7 used in our study, the arginine (pK > 11)26 and lysine (pK > 10.5)26,27 side chains of tat peptide should be protonated and available for salt bridge (SB) formation with the deprotonated RNA phosphodiester moieties (pK 1–3).28 We attributed the unusual strength of TAR–tat interactions in the gas phase to electrostatic interactions, of which salt bridges are thought to provide the highest contribution to stability.20,29 However, the question remains as to how many and what types of interactions, alone or in combination, are sufficient for probing of RNA–ligand binding sites by CAD.

Thermodynamic information for noncovalent interactions of small gaseous complexes has been determined with high accuracy,30,31 but it is challenging, if not impossible, to obtain data for larger systems in which the strength of individual neutral (10–40 kJ/mol)30,32,33 and ionic (20–170 kJ/mol)30,33 hydrogen bonds (HB) is modulated by other charges and noncovalent bonds. Likewise, the stability of salt bridges between protonated basic (e.g., arginine side chains) and deprotonated acidic (e.g., RNA phosphodiester moieties) sites is strongly affected by the number and distribution of other charges and the hydrogen-bonding network. Williams and co-workers recently found that this is the case even for small complexes: As a result of differing hydrogen bond networks and net charges, glycine dimer anions and cations have SB and HB interfaces, respectively.34 Here, we have studied the relative strength of noncovalent and covalent bonds in gaseous RNA–ligand complexes formed by association reactions in solution and ESI.35 Seven peptides (GR, VR, DR, ER, KR, RR, NGR) and the fixed-charge ligand tetramethylammonium (Tma) were investigated in 1:1 complexes with seven different RNAs (Table 1).

Table 1. RNAs Studied.

| RNA | sequence | possible hairpin structure | # A, G, C, U bases |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GGCUAGCC | yes | 1, 3, 3, 1 |

| 2 | AAUCGAUU | yes | 3, 1, 1, 3 |

| 3 | GGGAUCCC | yes | 1, 3, 3, 1 |

| 4 | AAAGCUUU | yes | 3, 1, 1, 3 |

| 5 | CAGACUGU | no | 2, 2, 2, 2 |

| 6 | ACUGCUAG | no | 2, 2, 2, 2 |

| 7 | CUCUCUCU | no | 0, 0, 4, 4 |

Experimental Section

Experiments were performed on a 7 T Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometer (Bruker, Austria) equipped with an ESI source, a linear quadrupole for ion isolation, and a collision cell through which a flow of Ar gas (0.2 L/s except when indicated otherwise) was maintained for CAD.36 RNA–ligand complexes were electrosprayed (1.5 μL/min) from solutions of RNA (1 μM) and ligand (5–100 μM) in 1:1 CH3OH/H2O at pH ∼ 7.5, adjusted by the addition of piperidine and imidazole (∼1.3 mM each). CH3OH was high-performance liquid chromatography grade (Acros, Vienna, Austria) and H2O was purified to 18 MΩ·cm using a Milli-Q system (Millipore, Austria). Dipeptide acetate salts were from Bachem (Bubendorf, Switzerland) and NGR and RNAs 2–7 from Sigma-Aldrich (Vienna, Austria), and used without further purification. RNA 1 was prepared by solid-phase synthesis and desalted as described in ref (37). According to theoretical predictions (http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/cgi-bin/RNAWebSuite/RNAfold.cgi),38 RNAs 1–7 should not form any stable secondary structures in solution, especially at the high methanol content used. However, RNAs 1–4 could potentially form hairpin structures in the presence of ligands.35 The CAD experiments were performed over a period of 18 months, and we did not observe any correlation between the order of experiments and the collision energy required for dissociation of the RNA or RNA–ligand complexes. Between 50 and 100 scans were added for each spectrum.

Results and Discussion

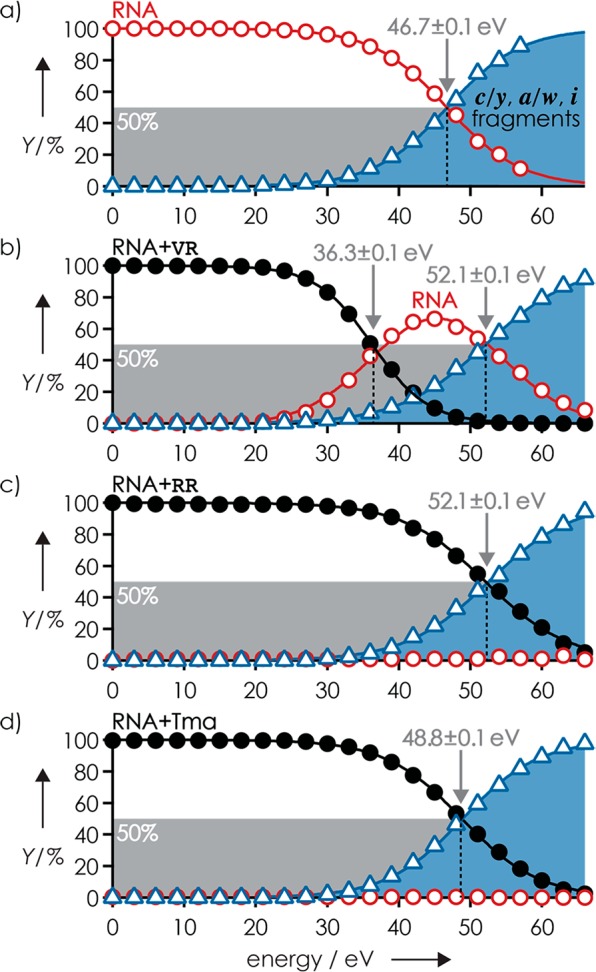

Figure 1 shows the yield of products from CAD of (M – 3H)3–, (M + VR – 3H)3–, (M + RR – 3H)3–, and (M + Tma – 4H)3– ions of RNA 1 versus collision energy. In agreement with earlier studies,10,36,39 CAD of the (M – 3H)3– ions produced predominantly c and y fragments from RNA phosphodiester backbone bond cleavage; at elevated collision energy, a and w fragments from C3′–O backbone bond cleavage and internal (i) fragments from secondary backbone bond cleavage appeared (Figure S1a). Products from loss of nucleobases and H2O from (M – 3H)3– and fragment ions were also observed (Figure S2a) and included in the calculation of RNA and fragment yields.

Figure 1.

Products from CAD of (a) (M – 3H)3–, (b) (M + VR – 3H)3–, (c) (M + RR – 3H)3–, and (d) (M + Tma – 4H)3– ions of RNA 1 versus laboratory-frame collision energy illustrate the competition between covalent RNA backbone bond cleavage into c/y, a/w, or i fragments (blue) and noncovalent bond dissociation into free RNA (red) and ligand; energies required for 50% complex dissociation and 50% fragment formation are indicated by arrows.

Similar products and product yields were observed in CAD of (M + Tma – 4H)3– ions of RNA 1 (Figure S1b), although the collision energy required for 50% fragment formation by breaking of covalent backbone bonds, E50(c), increased by ∼5% from 46.7 ± 0.1 to 48.8 ± 0.1 eV (Figure 1a,d). The increase in E50(c) can be attributed to the ∼6% increase in degrees of freedom (DOF) of the (M – 3H)3– and (M + Tma – 4H)3– ions from 777 to 825.40 CAD produced no free RNA from dissociation of Tma, and no c6, c7, a6, a7, or y7 fragments (w7 was not observed) without Tma were detected even at the highest collision energy used (Figure S3a). Moreover, none of their complementary fragments, y2, w2, w1, and c1 (a1 and y1 were not observed), carried Tma. Fragments from cleavage at sites 2–5 showed varying occupancy with Tma (Figure S3b), which suggests binding of Tma to residues 2–5. The occupancy values of c2 and c5 and their complements y6 and y3 were relatively constant over the collision energy range in which signal-to-noise ratios of c and y fragments with and without Tma attached were not limited by low yields (below 39 eV) or secondary backbone bond cleavage (above 57 eV), and added up to 105 ± 1% and 99 ± 1% for c2/y6 and c5/y3, respectively.

By contrast, the occupancy values of c3/y5 and c4/y4 fragments from cleavage at sites 3 and 4 varied strongly with collision energy, between ∼40% and ∼85%, and those from cleavage at site 4 added up to ∼130% (Figure S3b). The variation in occupancy values can be attributed to strong binding of Tma to both residues 3 and 4, and the competition between complementary fragments (c3 and y5, c4 and y4) for Tma during fragment separation. Strong binding of Tma to residues 3 and 4 is further indicated by the presence of CU in all internal fragments with Tma attached from CAD at the highest collision energy used (66 eV): i(GCUA + Tma), i(GCU + Tma), and i(CUA + Tma). The added occupancy values >100% likely result from the lower stability against secondary backbone cleavage of fragments without ligand attached compared to that of fragments with ligand attached.10 From the fact that no free RNA and even internal fragments with Tma attached were observed in CAD of (M + Tma – 4H)3– ions of RNA 1, we conclude that the noncovalent bonds between Tma and the RNA are far stronger than the covalent backbone bonds of the RNA. This order is consistent with the calculated interaction energy between gaseous Tma and dimethylphosphate of 355 kJ/mol41 and the energies for hydrolysis of dimethylphosphate by H2O42 and 2′,3′-ribose cyclic phosphate by CH3OH43 attack on the phosphorus atom of ∼190 and ∼225 kJ/mol, respectively.

The breakdown curves of the (M + RR – 3H)3– ions of RNA 1 were highly similar to those of the (M – 3H)3– and (M + Tma – 4H)3– ions (Figure 1); again, CAD produced no significant yields of free RNA at any of the collision energies used. The E50(c) of 52.1 ± 0.1 eV was ∼12% higher than that for (M – 3H)3–, which is close to the ∼16% increase in DOF of the (M – 3H)3– and (M + RR – 3H)3– ions from 777 to 924. However, the yield of c and y fragments with RR attached was lower by a factor of ∼0.7 than that for Tma (Figure S4), which indicates RR dissociation from the fragments at elevated collision energy. In support of this hypothesis, the added occupancy of c and y fragments with RR decreased with increasing collision energy (Figure S5). The lower stability of the noncovalent interactions between RR and the c, y fragments compared to that of Tma can be attributed to proton transfer (PT) within intermolecular salt bridges. In a recent CAD study of RNA 1 in complexes with guanidine or guanidine derivatives including R, we found that PT from protonated ligand (L) to a deprotonated phosphodiester moiety of the RNA, which converts the intermolecular salt bridge into a far weaker hydrogen bond, generally preceded ligand dissociation.35 Likewise, PT from a protonated guanidinium group of RR to a deprotonated phosphodiester moiety of a c or y fragment should precede loss of RR. However, protonated RR has a zwitterionic structure in the gas phase44 (Scheme 1) and can form two salt bridges with the RNA, such that transfer of two protons is required for SB to HB conversion. The higher stability of the noncovalent interactions of the (M + RR – 3H)3– ions over that of the complexes of RNA 1 with guanidine or its derivatives, all of which dissociated at collision energies below that required for covalent RNA backbone cleavage into c and y fragments,35 is consistent with higher energy requirements for transfer of two instead of one proton. Finally, the higher stability of the noncovalent interactions of Tma with RNA 1 compared to those of RR is consistent with a far higher proton affinity (PA) of deprotonated Tma (which is the corresponding, overall neutral base of Tma) compared to that of RR. This data suggests that the electrostatic energy between the positively charged ligands and deprotonated RNA is high enough to prevent ligand dissociation during CAD unless PT from ligand to RNA occurs.

Scheme 1. Structures of Gaseous (a) Tma, (b) (RR + H)+,44 and (c) (VR + H)+ 44.

The peptide ligands other than RR showed weaker binding to RNA 1 (Figure S6), and besides fragments from RNA backbone cleavage, CAD also produced free RNA as illustrated for VR in Figure 1b. Just like in our previous study,35 (M – 4H)4– RNA ions were not observed in CAD of the complexes with a net charge of −3, consistent with PT from protonated ligand to the RNA prior to ligand dissociation. The collision energy required for 50% ligand dissociation by breaking of noncovalent bonds, E50(nc), in CAD of the (M + VR – 3H)3– ions was 36.3 ± 0.1 eV, and the collision energy required for 50% fragment formation by breaking of covalent bonds, E50(c), was 52.1 ± 0.1 eV. Thus, for VR, E50(nc) is 69.6 ± 0.2% of E50(c). Furthermore, we found that increasing the rate of Ar gas flow through the collision cell36 by 50%, from 0.2 to 0.3 L/s, only slightly increased both E50(nc) (by 3%, from 36.3 ± 0.1 to 37.4 ± 0.1 eV) and E50(c) (by 4%, from 52.1 ± 0.1 to 54.1 ± 0.1 eV), but E50(nc) in % of E50(c) was, within error limits, the same at 0.3 L/s (69.2 ± 0.2%) and 0.2 L/s (69.6 ± 0.2%). Accordingly, small fluctuations in Ar gas flow rate (on the order of a few percentage points), and thus partial Ar pressure in the collision cell, should not significantly affect E50(nc), E50(c), or E50(nc) in % of E50(c).

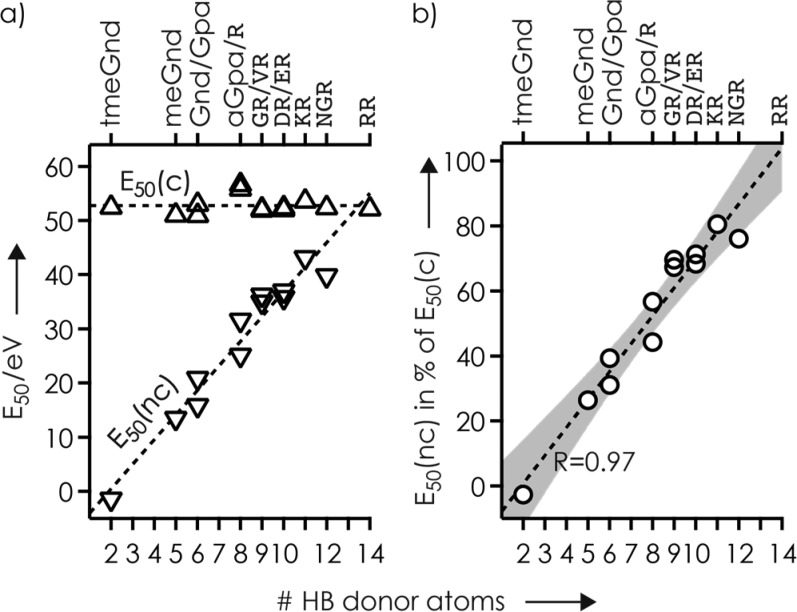

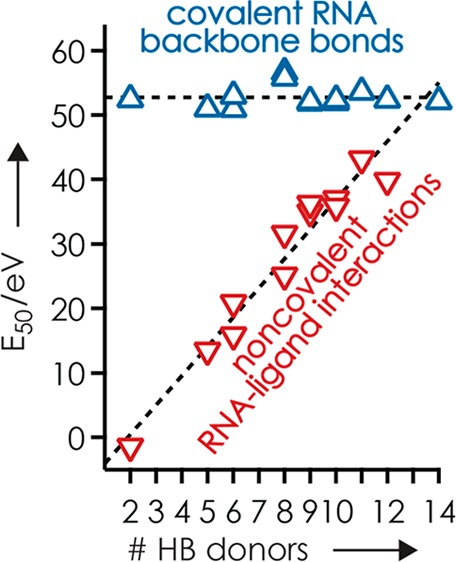

The E50(c) values for all ligands (Figure 2a), including those for the guanidine ligands from our previous study,35 showed little variation (average 52.8 eV, standard deviation ±1.7 eV) that can in part be attributed to differences in the number of DOF of the complexes (Figure S7, Table S1). By contrast, the E50(nc) values varied strongly, between −1.4 and 43.2 eV, which is up to 81% of the corresponding E50(c) values (Figure 2). The only ligand PA values available (tmeGnd, 1032 kJ/mol; Gnd, 986 kJ/mol; R, 1051 kJ/mol)45 did not correlate with complex stability, the order of which (tmeGnd < Gnd < R) cannot be attributed to differences in the number of DOF of the complexes either (tmeGnd, 843; Gnd, 798; R, 855).35 However, the E50(nc) values increased linearly with the number of hydrogen bond donors of the ligands (Figure 2, Scheme S1). E50(nc) values for GR, VR, DR, and ER were similar, which suggests that the side chain carboxylic acid functionalities were not involved in RNA–ligand binding. This hypothesis is supported by extensive loss of H2O loss46,47 from (M + DR – 3H)3– and (M + ER – 3H)3– ions (Figure S8). For ligands with the same number of HB donor atoms (Gnd/Gpa, aGpa/R, GR/VR, DR/ER), E50(nc) values of the ligands with the longer alkyl chain (Gpa, R, VR, ER) were consistently higher, suggesting that both inductive effects on PA and conformational flexibility alter complex stability. However, these effects are far smaller than that of the number of HB donor atoms (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(a) Collision energy required for 50% complex dissociation by cleavage of noncovalent bonds (E50(nc), ▽) and for 50% fragment formation by cleavage of covalent RNA backbone bonds (E50(c), △) in CAD of complexes with RNA 1 and net charge of −3, and (b) E50(nc) in % of E50(c), versus the number of HB donor atoms of the ligands; lines are linear fit functions and the gray area in (b) illustrates the 99% confidence interval.

The E50 values here are from CAD experiments under multiple-collision conditions, and calibration of the laboratory-frame collision energy scale to an internal energy scale is not straightforward.36,48,49 Nevertheless, because all complexes were studied under the same experimental conditions on the same instrument and are similar in size and composition and any effects of DOF cancel out when E50(nc) is expressed in % of E50(c) (Figure 2b), we can draw some solid conclusions from our data. The E50 values in Figure 2b show that HB interactions interfere with PT within intermolecular salt bridges,35 from the ligand guanidinium group to a deprotonated phosphodiester moiety of the RNA, and subsequent ligand dissociation in an additive manner. Schmuck and co-workers observed similar behavior in aqueous solution where the stability of complexes between guanidinium derivatives and dipeptide carboxylates was found to increase with increasing number of HBs between the binding partners.50,51

The linear fit function in Figure 2b extrapolates to 13.5 HB donor atoms at 100%, where E50(nc) is equal to E50(c), which is just below the 14 HB donor atoms of RR. However, the fit is to data for ligands with a single guanidinium group, and as discussed above, gaseous (RR + H)+ has a zwitterionic structure in which both guanidine side chains are protonated (Scheme 1); in (GR + H)+, (VR + H)+, and (KR + H)+, the only charged site is the guanidinium group.44 Thus, for RR, E50(nc) is probably far higher than E50(c), which is also indicated by the presence of fragments with RR attached at energies of up to 66 eV (Figure S4). For the ligands with a single guanidinium group, each hydrogen bond increased the stability of the RNA–ligand interaction by an average of 8.6% relative to E50(c). Assuming that E50(c) is close to the energy for hydrolysis of 2′,3′-ribose cyclic phosphate by CH3OH (∼225 kJ/mol),43 the average stabilization per HB would be ∼20 kJ/mol, which is typical for HBs in the gas phase.30,32,33

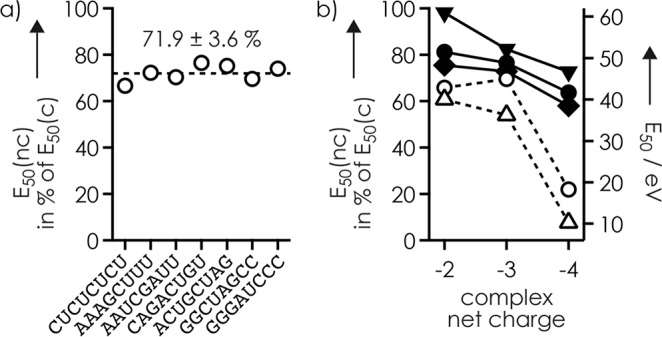

To address the effect of RNA structure on ligand binding, we determined E50 values for RNAs 1–7 in complexes with VR and RR (Figure 3a and Figure S9). Neither E50(nc) nor E50(c) showed a clear correlation with RNA sequence, composition, or possible secondary structure (Table 1), which indicates unspecific binding to phosphodiester moieties in nonhairpin structures without significant differences in stabilization by nucleobase interactions. Consistent with unspecific binding, the c and y fragments with VR and RR attached revealed binding to the phosphodiester moieties of residues 3 and 4 of RNAs 1–7 (Figure S10), just like Tma. Finally, we have studied the effect of net charge on complex stability. For both RNA 1 and its complexes with Tma and VR, the E50(c) values decreased nearly linearly with increasing charge (Figure 3b). A similar decrease was observed for the E50(nc) values for VR at −2 and −3, but that at −4 was substantially lower, such that E50(nc) in % of E50(c) was similar at −2 and −3, 65.7 ± 0.3% and 69.6 ± 0.2%, but only 22.0 ± 0.1% at −4. This can be rationalized by more facile PT and/or fewer hydrogen bonds in more extended structures at −4 (0.5 charges/nt) compared to that at lower net charge (0.25 and 0.375 charges/nt at −2 and −3, respectively).

Figure 3.

E50(nc) in % of E50(c) (○) for (a) complexes of VR and RNAs 1–7 with a net charge of −3 (the line indicates the average), and (b) the complex of VR and RNA 1 (left axis) versus net charge (also shown are E50(c) (▼, RNA + VR; ●, RNA + Tma; ◆, RNA) and E50(nc) (△, RNA + VR) values in eV (right axis).

Conclusions

In conclusion, we show that the interactions between Tma or (RR + H)+ and deprotonated RNA are strong enough to survive RNA backbone cleavage by CAD. By contrast, salt bridges between ligands with a single guanidinium group and RNA anions convert into far weaker hydrogen bonds, followed by loss of ligand, at energies that are sufficiently high for RNA backbone cleavage unless the RNA–ligand interaction is stabilized by additional hydrogen bonds. For complexes of different 8 nt RNA with di- and tripeptide ligands with a single arginine residue and a net charge of −3, additional stabilization by >13 hydrogen bonds increases the strength of the noncovalent interactions beyond that of the covalent RNA backbone bonds. Moreover, our data reveal similar stability of complexes with 0.25–0.375 charges/nt, but substantially reduced stability at 0.5 charges/nt. Because net charge can easily be adjusted by the use of ESI additives,52 probing ligand binding sites in RNA by top-down MS10 should be possible even for very small peptides or other basic ligands such as aminoglycosides. Importantly, our study is a major step toward rationalizing the contributions of individual noncovalent interactions to the overall stability of gaseous biomolecular complexes, and toward resolving the ongoing controversy of whether or not native top-down mass spectrometry can provide reliable information on binding interfaces.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF; P27347 and P30087 to K.B.) and the Austrian Research Promotion Agency (FFG; West-Austrian BioNMR). Funding for open access charge: Austrian Science Fund (FWF).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b05387.

Site-specific and overall yields of CAD products and fragment occupancies with ligands; E50(c), E50(nc), and DOF values; structures of protonated ligands with hydrogen bond donor atoms (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Marcoux J.; Robinson C. V. Structure 2013, 21, 1541–1550. 10.1016/j.str.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lossl P.; van de Waterbeemd M.; Heck A. J. R. EMBO J. 2016, 35, 2634–2657. 10.15252/embj.201694818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuker K. Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 114–116. 10.1038/nchem.2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuker K.; McLafferty F. W. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105, 18145–18152. 10.1073/pnas.0807005105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polfer N. C.; Oomens J. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2009, 28, 468–494. 10.1002/mas.20215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanucara F.; Holman S. W.; Gray C. J.; Eyers C. E. Nat. Chem. 2014, 6, 281–294. 10.1038/nchem.1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo T. R.; Boyarkin O. V. In Gas-Phase IR Spectroscopy and Structure of Biological Molecules; Rijs A.M., Oomens J., Eds.;Springer: 2015; pp 43–97. [Google Scholar]

- Servage K. A.; Silveira J. A.; Fort K. L.; Russell D. H. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 1421–1428. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.; Nguyen H. H.; Loo R. R. O.; Campuzano I. D. G.; Loo J. A. Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 139. 10.1038/nchem.2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneeberger E. M.; Breuker K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 1254–1258. 10.1002/anie.201610836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner O. S.; Haverland N. A.; Fornelli L.; Melani R. D.; Do Vale L. H. F.; Seckler H. S.; Doubleday P. F.; Schachner L. F.; Srzentic K.; Kelleher N. L.; Compton P. D. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 14, 36–41. 10.1038/nchembio.2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai L. B.; Tanimoto A.; Lai S. M.; Chen W. Y.; Marathe I. A.; Westhof E.; Wysocki V. H.; Gopalan V. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 7432–7440. 10.1093/nar/gkx388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X.; Lai L. B.; Lai S. M.; Tanimoto A.; Foster M. P.; Wysocki V. H.; Gopalan V. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 11483–11487. 10.1002/anie.201405362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saliou J. M.; Manival X.; Tillault A. S.; Atmanene C.; Bobo C.; Branlant C.; Van Dorsselaer A.; Charpentier B.; Cianferani S. Proteomics 2015, 15, 2851–2861. 10.1002/pmic.201400529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Duijn E.; Barbu I. M.; Barendregt A.; Jore M. M.; Wiedenheft B.; Lundgren M.; Westra E. R.; Brouns S. J.; Doudna J. A.; van der Oost J.; Heck A. J. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2012, 11, 1430–1441. 10.1074/mcp.M112.020263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delvaux D.; Murty M. R.; Gabelica V.; Lakaye B.; Lunin V. V.; Skarina T.; Onopriyenko O.; Kohn G.; Wins P.; De Pauw E.; Bettendorff L. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 34023–34035. 10.1074/jbc.M111.233585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabris D. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 5810–5816. 10.1021/ac200374y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabris D.; Turner K. B.; Kohlway A. S.; Hagan N. A. Biopolymers 2009, 91, 283–296. 10.1002/bip.21107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves S.; Woods A.; Tabet J. C. J. Mass Spectrom. 2007, 42, 1613–1622. 10.1002/jms.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schennach M.; Schneeberger E. M.; Breuker K. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2016, 27, 1079–1088. 10.1007/s13361-016-1363-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin S.; Xie Y. M.; Loo J. A. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2008, 19, 1199–1208. 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin S.; Loo J. A. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2010, 21, 899–907. 10.1016/j.jasms.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze-Gahmen U.; Echeverria I.; Stjepanovic G.; Bai Y.; Lu H. S.; Schneidman-Duhovny D.; Doudna J. A.; Zhou Q.; Sali A.; Hurley J. H. eLife 2016, 5, e15910. 10.7554/eLife.15910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel D. J. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1999, 9, 74–87. 10.1016/S0959-440X(99)80010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkar A. N.; Bardaro M. F.; Camilloni C.; Aprile F. A.; Varani G.; Vendruscolo M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113, 7171–7176. 10.1073/pnas.1521349113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurlkill R. L.; Grimsley G. R.; Scholtz J. M.; Pace C. N. Protein Sci. 2006, 15, 1214–1218. 10.1110/ps.051840806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimsley G. R.; Scholtz J. M.; Pace C. N. Protein Sci. 2008, 18, 247–251. 10.1002/pro.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown W. H.; Iverson B. L.; Anslyn E. V.; Foote C. S.. Organic Chemistry, 7th ed.; Cengage Learning, Boston, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schennach M.; Breuker K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 164–168. 10.1002/anie.201306838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meot-Ner M. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, PR22–PR103. 10.1021/cr200430n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers M. T.; Armentrout P. B. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 5642–5687. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BenTal N.; Sitkoff D.; Topol I. A.; Yang A. S.; Burt S. K.; Honig B. J. Phys. Chem. B 1997, 101, 450–457. 10.1021/jp961825r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeegers-Huyskens T. J. Mol. Struct.: THEOCHEM 1986, 135, 93–103. 10.1016/0166-1280(86)80049-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heiles S.; Cooper R. J.; Berden G.; Oomens J.; Williams E. R. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 30642–30647. 10.1039/C5CP06120B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vusurovic J.; Schneeberger E. M.; Breuker K. ChemistryOpen 2017, 6, 739–750. 10.1002/open.201700143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taucher M.; Rieder U.; Breuker K. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2010, 21, 278–285. 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosutic M.; Jud L.; Da Veiga C.; Frener M.; Fauster K.; Kreutz C.; Ennifar E.; Micura R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 6656–6663. 10.1021/ja5005637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofacker I. L. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 3429–3431. 10.1093/nar/gkg599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riml C.; Glasner H.; Rodgers M. T.; Micura R.; Breuker K. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 5171–5181. 10.1093/nar/gkv288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellen E. E.; Chappell A. M.; Ryzhov V. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2002, 16, 1799–1804. 10.1002/rcm.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavri J.; Vogel H. J. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Genet. 1994, 18, 381–389. 10.1002/prot.340180408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro A. J. M.; Ramos M. J.; Fernandes P. A. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010, 6, 2281–2292. 10.1021/ct900649e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez X.; Dejaegere A.; Leclerc F.; York D. M.; Karplus M. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 11525–11539. 10.1021/jp0603942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prell J. S.; O’Brien J. T.; Steill J. D.; Oomens J.; Williams E. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 11442–11449. 10.1021/ja901870d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter E. P.; Lias S. G. In NIST Chemsitry WebBook, NIST Standard Reference Database Number 69; Linstrom P. J., Mallard W. G., Eds.: National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, http://webbook.nist.gov, retrieved September 6, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison A. G. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2001, 210, 361–370. 10.1016/S1387-3806(01)00405-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison A. G.; Young A. B. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2006, 255, 111–122. 10.1016/j.ijms.2005.12.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers M. T.; Armentrout P. B. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2000, 19, 215–247. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demireva M.; Williams E. R. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2010, 21, 1133–1143. 10.1016/j.jasms.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmuck C. Chem. - Eur. J. 2000, 6, 709–718. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmuck C.; Geiger L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 8898–8899. 10.1021/ja048587v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganisl B.; Taucher M.; Riml C.; Breuker K. Eur. J. Mass Spectrom. 2011, 17, 333–343. 10.1255/ejms.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.