Abstract

Objectives

Induction chemotherapy (IC) now is gaining recognition for the treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC). The current study was conducted to examine the association between prognosis and the interval between IC and radiotherapy (RT) in NPC patients.

Methods

Patients with newly diagnosed, non-metastatic NPC who were treated with IC followed by RT from 2009 to 2012 were identified from an inpatient database. Overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS), distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) and locoregional recurrence-free survival (LRFS) were compared between those with interval ≤ 30 and > 30 days by Kaplan-Meier and log-rank analyses; Cox modeling was used for multivariable analysis.

Results

A total of 668 patients met inclusion criteria with median follow-up of 64.4 months. Patients were categorized by interval: 608 patients with interval ≤ 30 days, and 60 with interval > 30 days. The 5-year OS, DFS, DMFS and LRFS rates were 86.6, 78.2, 88.0 and 89.8% for patients with interval ≤ 30 days, respectively, and 69.2, 64.5, 71.2 and 85.1% for patients with interval > 30 days, respectively. The prolonged interval was a risk factor for OS, DFS and DMFS with adjusted hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) were 2.44 (1.48–4.01), 1.99 (1.27–3.11) and 2.62 (1.54–4.47), respectively.

Conclusions

Prolonged interval > 30 days was associated with a significantly higher risk of distant metastasis and death in NPC patients. Efforts should be made to avoid prolonged interval between IC and RT to minimize the risk of treatment failure.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13014-019-1213-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Interval, Induction chemotherapy, Radiotherapy, Prognosis

Background

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is endemic in southern China, where the age-standardized annual incidence was 5–11 cases per 100,000 in endemic provinces, increasing to 10–27 cases in endemic counties [1]. Due to the anatomic constraints and high radio-sensitivity of NPC, radiotherapy (RT) has become the primary curative treatment. For patients with stage I NPC, RT alone had good efficacy, and led to a 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of over 90% [2]. However, for patients with stage II-IV NPC, accounting for over 90% of the newly-diagnosed cases [3], RT combined with chemotherapy (chemoradiotherapy, CRT) was the recommended standard treatment [4].

Thanks to the introduction of intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) that offered improved target conformity and allowed safer dose escalations, locoregional control has improved substantially compared to 2-dimensional RT, and distant metastasis is now the main consequence of treatment failure [5]. Recently, an individual patient data pooled analysis [6] demonstrated that induction chemotherapy (IC), also known as neoadjuvant chemotherapy, may effectively decrease the distant metastasis rate and improve survival. However, the optimal interval between IC and RT remains unclear.

The prognostic effects of the interval between neoadjuvant treatment and definitive treatment have been studied for rectal [7], breast [8], and non-small cell lung [9] cancer. Chen et al. [10] reported that a prolonged wait time (> 4 weeks) between diagnosis and RT may worsen disease-free survival (DFS) rate for NPC patients. However, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no studies regarding the prognostic value of the interval between IC and RT in NPC. Therefore, we conducted this retrospective study to investigate the prognostic effect of the interval between IC and RT in NPC patients who received IC prior to RT. We hypothesized that the longer interval between IC and RT would be associated with worse survival in NPC patients.

Methods

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed an inpatient database that included 2191 patients with newly diagnosed, biopsy-proven, non-metastatic NPC treated at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center between November 2009 and October 2012. Patients receiving IC before RT were included, while patients without pretreatment plasma Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) DNA data were excluded.

Pretreatment evaluation and treatment

All patients underwent a comprehensive pretreatment evaluation, including complete history, physical examination, hematology and biochemistry profiles, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the neck and nasopharynx, chest radiography, abdominal.

ultrasonography, and whole-body bone scanning using single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). Positron emission tomography and computed tomography (PET/CT) was performed when necessary. All patients were restaged according to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer/International Union against Cancer (AJCC/UICC) staging system based on imaging materials and medical records.

The nasopharyngeal and neck tumor volumes of all patients were treated using radical radiotherapy based on IMRT for the entire course. Gross tumor volumes were defined based on MR, CT and PET/CT imaging before IC; target volumes were delineated slice-by-slice on treatment planning CT scans using an individualized delineation protocol [11], in accordance with the International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements reports 50 and 62. The prescribed doses were 66–72 Gy to the planning target volume (PTV) of the primary gross tumor volume (GTVnx), 64–70 Gy to the PTV of the GTV of involved lymph nodes (GTVnd), 59.4–63 Gy to the PTV of the high-risk clinical target volume (CTV1), and 50.4–56 Gy to the PTV of the low-risk clinical target volume (CTV2) in 28–33 fractions. All targets were treated simultaneously using the simultaneous integrated boost technique.

During the study, institutional guidelines recommended IMRT alone for stage I NPC and IMRT combined with chemotherapy for stage II-IVa NPC. Three regimes of IC were frequently used: cisplatin (80 mg/m2) with 5-fluorouracil (750–1000 mg/m2 per day for 5 days), cisplatin (75 mg/m2) with docetaxel (75 mg/m2), and cisplatin (60 mg/m2) plus docetaxel (60 mg/m2) with 5-fluorouracil (600–750 mg/m2 per day for 5 days) every 3 weeks for 2–4 cycles. Concurrent chemotherapy consisted of cisplatin (80–100 mg/m2) every 3 weeks for 2–3 cycles or cisplatin (30–40 mg/m2) weekly for 5–7 cycles. Adjuvant chemotherapy was less often chosen because of poor compliance. When possible, salvage treatments (intracavitary brachytherapy, surgery, or chemotherapy) were provided for documented relapse or persistent disease.

Variables and follow-up

The interval between IC and RT was calculated from the last day of the last cycle of IC to the initiation of RT. Analyzed covariates were as follows: tumor factors, including T category, N category, WHO pathology type and pretreatment plasma EBV DNA concentration; host factors, including age, gender and Charlson comorbidity index (CCI); treatment factors, including IC cycles and use or non-use of concurrent chemotherapy. Pretreatment plasma EBV DNA quantification was performed by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay amplifying the BamHI-W region of the EBV genome [12]. We added 1 to all EBV DNA values and then performed a natural log transformation to generate a new variable, lnDNA. Charlson comorbidity index was calculated based on medical records to assess the comorbidities [13].

The follow-up duration was measured from first day of treatment to the day of last examination or death. Patients were examined at least every 3 months during the first 2 years, then every 6 months for at least 3 years, and annually thereafter until death. The primary endpoint was OS, defined as the time from the initiation of therapy to death from any cause. The secondary endpoints included DFS, defined as the time from initiation of therapy to failure or death from any cause, whichever occurred first. Distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) was defined as the time from initiation of therapy to first distant failure. Locoregional recurrence-free survival (LRFS) was defined as the time from initiation of therapy to first locoregional failure.

Statistical analysis

We intended to dichotomize the interval for simplification of the analysis and better interpretation of the results. Because there was no referenced cutoff point reported previously, we categorized the interval into five consecutive groups to explore the relationship between the interval and OS preliminarily, and we then determined a suitable cutoff point. The associations between the dichotomized interval and other binary or nominal variables were tested with Pearson chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Independent samples t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test were used for continuous and ordinal variables. Actuarial survival rates were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and survival curves were compared using log-rank test. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each covariate were estimated from univariate Cox regression analyses. The multivariate Cox regression model was used to adjust prognostic effects of the interval for other prognostic factors. Covariates were selected by a backward elimination method with removal criterion of 0.2. The interval and selected covariates entered the multivariate analyses. Age and lnDNA were modeled as continuous variables assuming linear correlation with the outcomes, while the interval and other covariates were modeled as binary variables. Heterogeneity of effect size in different subgroups was appraised by I2 statistic, and a value > 25% indicated the existence of heterogeneity [14]. SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA), and Stata version 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) were used for all statistical analyses. Two-tailed P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Totally, 1901 of the 2191 patients recorded in database received RT combined with chemotherapy, of which 1086 patients received IC before RT. After 418 patients without EBV DNA data were excluded, 668 patients with complete data were included in subsequent analyses (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Baseline characteristics of included and excluded patients are shown in Additional file 2.

The median follow-up duration for the included 668 patients was 64.4 months (range, 4.57–91.5 months). In total, 108 patients died, 158 experienced failure or died, 89 experienced distant failure, and 70 experienced locoregional failure. The relationships among death, distant and locoregional failure is shown in a Venn diagram (Additional file 1: Figure S2); 95/108 patients died of cancer while 13/108 patients died non-cancer-related deaths. Of the 95 cancer-specific deaths, 68 patients experienced distant metastasis and 40 patients experienced locoregional recurrence. We observed that patients with locoregional recurrence were at less risk of death than were patients with distant metastasis, possibly due to the success of locoregional salvage treatments. The 5-year OS, DFS, DMFS and LRFS rates were 85.0, 77.0, 86.5 and 89.4% respectively.

Cutoff point of the interval

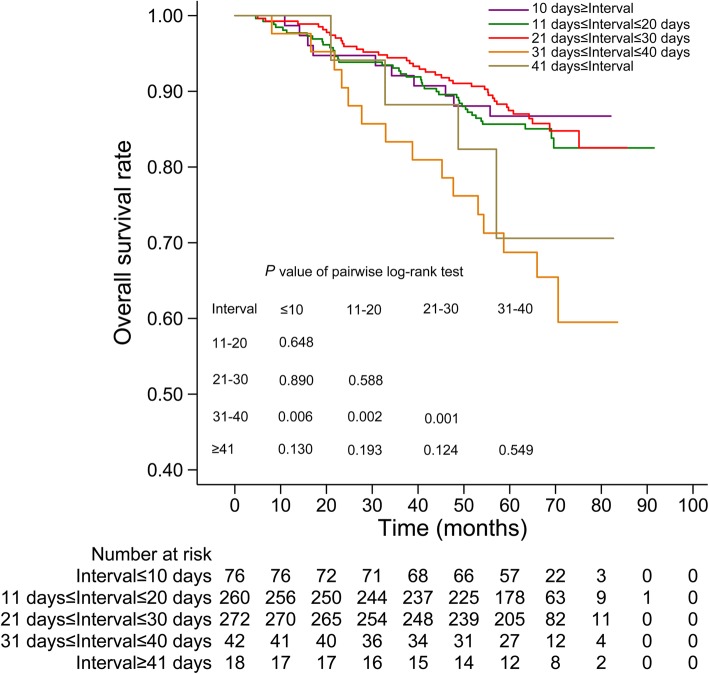

The median interval between IC and RT was 20 days (range, 1–67 days; interquartile range, 15–27 days). Three extreme values of 61, 66 and 67 were confirmed by review of medical records. We categorized the interval into ≤10, 11–20, 21–30, 31–40 and ≥ 41 groups, and the 5-year OS rates were 86.7, 85.7, 87.5, 68.7 and 70.6%, respectively. The log rank test showed no significant differences among ≤10, 11–20 and 21–30 groups and between 31 and 40 and ≥ 41 groups (Fig. 1). Therefore, we chose 30 days as the cutoff point to categorize the interval into a ≤ 30 days group with a median of 19 (interquartile range, 14–25) and a > 30 days group with a median of 36 (interquartile range, 32–42).

Fig. 1.

The OS curves based on the interval categorized into five groups. OS, overall survival

Patients characteristics and association with the interval

Patient characteristics for the entire included cohort are displayed in Table 1. Patients with the interval > 30 days tended to receive more cycles of IC (P < 0.001) and were less likely to receive concurrent chemotherapy during RT (P = 0.028) than were patients with interval ≤ 30 days. We also observed that patients in the > 30 days group were more likely to be at advanced T categories (P = 0.034). However, after we recategorized T categories as binary variables (T1–2 and T3–4) before entering the Cox regression, the correlation between T categories and the interval became statistically insignificant (Pearson chi-square test, P = 0.154, data not shown). As for the remaining characteristics, no significant correlation between these and the interval was found, even after some of them were recategorized into binary variables (CCI, 0 and ≥ 1; N categories, N0–1 and N2–3; WHO pathology, I/II and III).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 668 included patients

| Characteristics | Interval ≤ 30 days (608 patients) | Interval > 30 days (60 patients) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 44.5 ± 11.0 | 44.8 ± 11.2 | 0.808a |

| Gender | 0.304b | ||

| Male | 462 (76.0%) | 42 (70.0%) | |

| Female | 146 (24.0%) | 18 (30.0%) | |

| CCI score | 0.088c | ||

| 0 | 519 (85.4%) | 56 (93.3%) | |

| 1 | 87 (14.3%) | 4 (6.7%) | |

| ≥ 2 | 2 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| T categorye | 0.034c | ||

| T1 | 54 (8.9%) | 3 (5.0%) | |

| T2 | 86 (14.1%) | 6 (10.0%) | |

| T3 | 299 (49.2%) | 27 (45.0%) | |

| T4 | 169 (27.8%) | 24 (40.0%) | |

| N categorye | 0.211c | ||

| N0 | 47 (7.7%) | 5 (8.3%) | |

| N1 | 339 (55.8%) | 29 (48.3%) | |

| N2 | 101 (16.6%) | 7 (11.7%) | |

| N3 | 121 (19.9%) | 19 (31.7%) | |

| Stagee | 0.105c | ||

| II | 77 (12.7%) | 7 (11.7%) | |

| III | 263 (43.3%) | 19 (31.7%) | |

| IVa | 268 (44.1%) | 34 (56.7%) | |

| EBV DNA (103 copies/ml) | 5.6 (0–3290) | 6.1 (0–3660) | 0.476c |

| lnDNAf | 7.5 ± 4.0 | 7.8 ± 4.1 | 0.504a |

| WHO pathology | 0.728d | ||

| I | 6 (1.0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| II | 28 (4.6%) | 4 (6.7%) | |

| III | 574 (94.4%) | 56 (93.3%) | |

| IC cycles | < 0.001c | ||

| 1 | 75 (12.3%) | 5 (8.3%) | |

| 2 | 315 (51.8%) | 21 (35.0%) | |

| 3 | 187 (30.8%) | 18 (30.0%) | |

| ≥ 4 | 31 (5.1%) | 16 (26.7%) | |

| Concurrent chemotherapy | 0.028b | ||

| Yes | 497 (81.7%) | 42 (70.0%) | |

| No | 111 (18.3%) | 18 (30.0%) |

Data presented as number (%), mean ± standard deviation or median (range)

Abbreviations: CCI Charlson comorbidity index, EBV Epstein-Barr virus, IC Induction chemotherapy

aIndependent samples t-test

bPearson chi-square test

cWilcoxon rank-sum test

dFisher’s exact test

eAccording to the 8th edition of AJCC/UICC staging system

flnDNA = ln (EBV DNA × 1000 + 1)

Prognostic effect of the interval for NPC patients

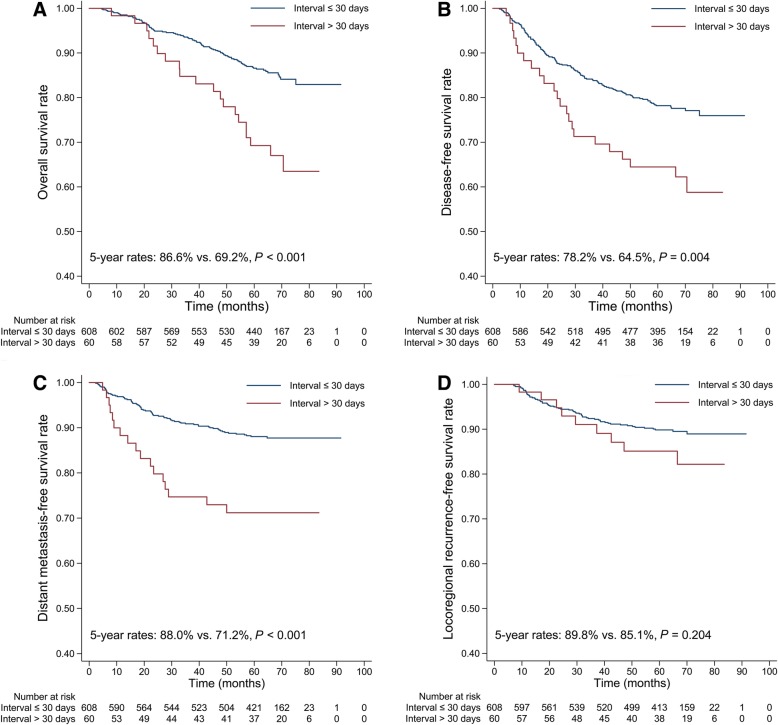

The 5-year OS rate was significantly lower for patients with interval > 30 days than for those with interval ≤ 30 days (69.2% vs. 86.6%, P < 0.001; Fig. 2a). The 5-year DFS rate (64.5% vs. 78.2%, P = 0.004; Fig. 2b) and DMFS rate (71.2% vs. 88.0%, P < 0.001; Fig. 2c) were also significantly lower for patients with interval > 30 days than for those with interval ≤ 30 days. However, the difference in 5-year LRFS rate (85.1% vs. 89.8%, P = 0.204; Fig. 2d) failed to reach significance. The unadjusted HRs and 95% CIs for the interval and other covariates estimated from univariate Cox regression are shown in Table 2.

Fig. 2.

The OS (a), DFS (b), DMFS(c), and LRFS (d) curves based on the interval categorized into two groups. OS, overall survival; DFS, disease-free survival; DMFS, distant metastasis-free survival; LRFS, locoregional recurrence-free survival

Table 2.

Univariate analyses of the interval and other covariates based on Cox regression model

| Factors | OS | DFS | DMFS | LRFS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P* | HR (95% CI) | P* | HR (95% CI) | P* | HR (95% CI) | P* | |

| Interval between IC and RT (> 30 vs. ≤ 30 days) | 2.43 (1.49–3.95) | < 0.001 | 1.90 (1.22–2.95) | 0.005 | 2.67 (1.57–4.53) | < 0.001 | 1.57 (0.78–3.16) | 0.208 |

| Age (continuous) | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | 0.010 | 1.02 (1.00–1.03) | 0.040 | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) | 0.899 | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.240 |

| Sex (Female vs. Male) | 0.85 (0.54–1.34) | 0.487 | 1.00 (0.69–1.43) | 0.985 | 1.04 (0.65–1.67) | 0.866 | 1.24 (0.74–2.07) | 0.425 |

| T category (T3–4 vs. T1–2) | 1.45 (0.87–2.41) | 0.149 | 1.28 (0.86–1.92) | 0.228 | 1.15 (0.68–1.92) | 0.608 | 1.54 (0.81–2.92) | 0.192 |

| N category (N2–3 vs. N0–1) | 2.22 (1.52–3.24) | < 0.001 | 1.66 (1.21–2.28) | 0.002 | 3.17 (2.08–4.85) | < 0.001 | 0.82 (0.49–1.38) | 0.464 |

| lnDNA (continuous) | 1.06 (1.01–1.12) | 0.022 | 1.07 (1.02–1.12) | 0.004 | 1.17 (1.09–1.26) | < 0.001 | 1.04 (0.98–1.11) | 0.187 |

| WHO pathology (III vs. I/II) | 0.59 (0.30–1.18) | 0.135 | 0.75 (0.41–1.39) | 0.361 | 1.25 (0.46–3.41) | 0.661 | 0.43 (0.21–0.90) | 0.025 |

| CCI (≥ 1 vs. 0) | 2.03 (1.29–3.21) | 0.002 | 1.74 (1.18–2.57) | 0.005 | 1.22 (0.69–2.16) | 0.496 | 1.38 (0.74–2.58) | 0.310 |

| IC cycles (> 2 vs. ≤ 2) | 1.29 (0.88–1.89) | 0.187 | 1.25 (0.91–1.71) | 0.170 | 1.39 (0.92–2.12) | 0.118 | 1.26 (0.79–2.03) | 0.336 |

| Concurrent chemotherapy (Yes vs. No) | 0.97 (0.60–1.56) | 0.903 | 0.99 (0.67–1.46) | 0.946 | 1.10 (0.64–1.89) | 0.728 | 1.05 (0.58–1.92) | 0.869 |

Abbreviations: OS Overall survival, DFS Disease-free survival, DMFS Distant metastasis-free survival, LRFS Locoregional recurrence-free survival, HR Hazard ratio, CI Confidence interval, IC Induction chemotherapy, RT Radiotherapy, CCI Charlson comorbidity index

*Wald chi-square test

Results of multivariable analyses are presented in Table 3. The interval > 30 days remained a significant negative prognostic factor for NPC patients in terms of OS (HR 2.44, 95% CI 1.48–4.01), DFS (HR 1.99, 95% CI 1.27–3.11) and DMFS (HR 2.62, 95% CI 1.54–4.47).

Table 3.

Multivariate analyses of prognostic factors based on Cox regression model

| Outcomes | Variables in the final model | HR (95% CI) | P* |

|---|---|---|---|

| OS | Interval (> 30 vs. ≤ 30 days) | 2.44 (1.48–4.01) | < 0.001 |

| N category (N2–3 vs. N0–1) | 2.13 (1.44–3.16) | < 0.001 | |

| CCI (≥ 1 vs. 0) | 2.21 (1.38–3.54) | 0.001 | |

| Age (continuous) | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.042 | |

| lnDNA (continuous) | 1.04 (0.98–1.10) | 0.173 | |

| T category (T3–4 vs. T1–2) | 1.42 (0.85–2.36) | 0.183 | |

| DFS | Interval (> 30 vs. ≤ 30 days) | 1.99 (1.27–3.11) | 0.003 |

| CCI (≥ 1 vs. 0) | 1.87 (1.26–2.79) | 0.002 | |

| N category (N2–3 vs. N0–1) | 1.58 (1.14–2.18) | 0.006 | |

| lnDNA (continuous) | 1.06 (1.01–1.10) | 0.018 | |

| Age (continuous) | 1.01 (1.00–1.03) | 0.126 | |

| DMFS | Interval (> 30 vs. ≤ 30 days) | 2.62 (1.54–4.47) | < 0.001 |

| N category (N2–3 vs. N0–1) | 3.03 (1.93–4.77) | < 0.001 | |

| lnDNA (continuous) | 1.12 (1.04–1.20) | 0.002 | |

| CCI (≥ 1 vs. 0) | 1.50 (0.84–2.66) | 0.171 | |

| LRFS | Interval (> 30 vs. ≤ 30 days) | 1.53 (0.76–3.08) | 0.238 |

| WHO pathology (III vs. I/II) | 0.42 (0.20–0.89) | 0.023 | |

| N category (N2–3 vs. N0–1) | 0.63 (0.37–1.07) | 0.086 | |

| lnDNA (continuous) | 1.06 (0.99–1.13) | 0.099 |

Covariates including: age (continuous), gender (female vs. male), CCI score (≥ 1 vs. 0), T category (T3–4 vs. T1–2), N category (N2–3 vs. N0–1), lnDNA (continuous), WHO pathology type (III vs. I/II), IC cycles (> 2 vs. ≤ 2), concurrent chemotherapy (yes vs. no)

Abbreviations: OS Overall survival, DFS Disease-free survival, DMFS Distant metastasis-free survival, LRFS Locoregional recurrence-free survival, IC Induction chemotherapy, CCI Charlson comorbidity index, HR Hazard ratio, CI Confidence interval

*Wald chi-square test

Subgroup analyses

We further explored the prognostic effects of the interval in subgroups stratified by N category, IC cycles and concurrent chemotherapy. For patients with N2–3 disease, the interval remained a significant prognostic factor in terms of OS, DFS and DMFS. By contrast, the interval may not exert a significant impact on OS, DFS and DMFS for patients with N0–1 disease (Additional file 1: Figure S3). After the cohort was stratified by IC cycles (Additional file 1: Figure S4) or concurrent chemotherapy (Additional file 1: Figure S5), the interval remained a significant prognostic factor, indicating its independence.

Heterogeneity analyses of effect size of the interval in subgroups suggested the existence of a modification effect by N category and concurrent chemotherapy. The interval > 30 days may be more dangerous for patients with advanced N category or not receiving concurrent chemotherapy during RT in terms of OS and DFS. Heterogeneity was not detected in terms of DMFS, possibly due to the lower number of events in subgroups. (Additional file 1: Figure S6)

To help readers gain a general understanding of our study, we provided a study profile recommended by the Reporting Recommendations for Tumor Marker Prognostic Studies (REMARK) [15] in Table 4.

Table 4.

The REMARK profile

| (a) Patients, treatment and variables | |||

| Study and marker | Remarks | ||

| Prognostic factor | M = the interval between IC and RT (days from the end of the last cycle of IC to the initiation of RT); categorized into 5 groups (≤ 10, 11–20, 21–30, 31–40 and ≥ 41), or 2 groups (≤ 30 and > 30) | ||

| Further variables | v1 = age, v2 = gender, v3 = CCI score, v4 = T category, v5 = N category, v6 = lnDNA, v7 = WHO pathology type, v8 = IC cycles, v9 = concurrent chemotherapy | ||

| Patients | Number | Remarks | |

| Assessed for eligibility | 2191 | Disease: newly diagnosed, biopsy-proven, non-metastatic NPC Patient source: 2009.11–2012.10, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center |

|

| Excluded | 1523 | Exclusion criteria: not receiving IC before RT; without pretreatment plasma EBV DNA | |

| Included | 668 | Treatment: all received IC and IMRT with or without concurrent chemotherapy | |

| Primary outcome events | |||

| OS | 108 | OS: from the initiation of therapy to death from any cause | |

| Secondary outcomes events | |||

| DFS | 158 | DFS: from the initiation of therapy to failure or death from any cause, whichever occurred first | |

| DMFS | 89 | DMFS: from the initiation of therapy to first distant failure | |

| LRFS | 70 | LRFS: from the initiation of therapy to first locoregional failure | |

| (b) Statistical analyses of survival outcomes | |||

| Analysis | Variables considered | Results/remarks | |

| A1: Univariate for OS | M | Fig. 1; the interval was categorized into 5 groups | |

| A2: Univariate for OS, DFS, DMFS, LRFS | M, v1-v9 | Fig. 2, Table 2; the interval was categorized into 2 groups | |

| A3: Multivariate for OS, DFS, DMFS, LRFS | M, v1-v9 | Table 3; variables in final model: OS (M, v1, v3, v4, v5, v6), DFS (M, v1, v3, v5, v6), DMFS (M, v3, v5, v6), LRFS (M, v5, v6, v7) | |

| A4: Interval in v5 subgroups for OS, DFS, DMFS | M, v5 | Additional file 1: Figures S3 and S6 | |

| A5: Interval in v8 subgroups for OS, DFS, DMFS | M, v8 | Additional file 1: Figures S4 and S6 | |

| A6: Interval in v9 subgroups for OS, DFS, DMFS | M, v9 | Additional file 1: Figures S5 and S6 | |

Abbreviations: IC Induction chemotherapy, RT Radiotherapy, CCI Charlson comorbidity index, NPC Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, EBV Epstein-Barr virus, IMRT Intensity modulated radiotherapy, OS Overall survival, DFS Disease-free survival, DMFS Distant metastasis-free survival, LRFS Locoregional recurrence-free survival

Discussion

As pretreatment plasma EBV DNA is an important prognostic factor for NPC patients, especially in predicting the distant metastasis [16], we excluded patients without EBV DNA data to minimize the potential confounding bias. Since the distribution of clinicopathologic factors (age, gender, T category, N category, overall stage and WHO pathology type) between the included cohort and the excluded cohort without EBV DNA data was statistically equivalent, the selection bias seemed to be not existent.

Both univariate and multivariate analyses revealed that prolonged interval > 30 days between IC and RT was a negative prognostic factor for NPC compared to the interval ≤ 30 days, with 2.44-fold increased risk of death, 1.99-fold increased the risk of failure or death, and 2.62-fold increased risk of distant failure. However, the interval was not associated with the risk of locoregional failure. Considering information of the Venn diagram (Additional file 1: Figure S2), we could infer that the worse OS and DFS rates associated with prolonged interval were caused by the worse DMFS, when the LRFS remained unchanged due to good locoregional control of IMRT.

The reason for an association between the interval and prognosis of NPC patients is likely complex and multifactorial. In multivariate analyses, we set a loose criterion for selecting covariates to avoid neglecting the potential important prognostic factors and to better adjust for effects of the interval. In the cohort, we found that the interval was associated with two other treatment factors, IC cycles and concurrent chemotherapy, however neither factor was selected into the final multivariate models. Considering this, we further conducted subgroup analyses and confirmed the independent impact of interval on NPC patients.

A study from Taiwan [17] reported that NPC patients with more comorbidities were associated with a prolonged wait time from diagnosis to RT, however, patients in this cohort did not receive IC before RT. In our cohort, there was no significant association between the interval between IC and RT and comorbidities, possibly due to most patients (666/668) being scored 0 or 1 by CCI, indicating relatively mild comorbidities. We found that comorbidity was an important prognostic factor for NPC patients in terms of OS and DFS, in accordance with study reported by Guo et al. [18]. After adjusting for CCI in the multivariate analyses, the interval remained a prognostic factor with statistical significance in terms of OS, DFS and DMFS.

A possible explanation is that the prolonged interval between IC and RT increased the risk of micro-metastasis from the locoregional lesions. IC was thought to be favorable for eradication the micro-metastasis and shrinking of locoregional lesions [19, 20], however the definitive eradication of locoregional lesions could not be achieved without RT. We postulated that tumor cells may leave locoregional lesions for distant metastasis during the interval when no anti-tumor treatment was used. The longer the interval between IC and RT, the greater the risk of micro-metastasis. However, for patients with early N categories at a low risk of distant metastasis, the interval may not exert impact on prognosis. On subgroup analysis, we also observed that concurrent chemotherapy during RT may weaken the risk posed by prolonged interval, attributable to the advantage of eradicating micro-metastasis by systemic therapy [21]. Chen et al. [10] also reported that NPC patients who did not receive IC before RT may be more vulnerable to distant failure as wait time from diagnosis to RT increased, also indicating that tumor may be more likely to progress during the anti-tumor treatment-free period. However, we believed that there should be a threshold of the interval considering the concept of chemotherapy dose intensity and the characterization of tumor cell cycle kinetics [22]. Therefore, a cutoff point to dichotomize the interval should be appropriate.

We observed that the prolonged interval between IC and RT was often caused by severe chemotherapy-related complications, after the hospital crowding problem was solved by augmentation of RT instruments and optimization of RT process at our institution. Due to the retrospective nature of our study, the IC related complications were difficult to evaluate, and we could not adjust for complications in the multivariate analyses. Though complications may influence the survival of patients, tumor control may not have direct associations with complications per se [23]. A multidisciplinary team approach may help prevent and treat complications and avoid prolonging the interval between IC and RT [24]. Adding another cycle of IC may be a way to avoid prolonged interval in cases where RT was delayed for other unexpected reasons, though Peng et al. [25] thought two cycles of IC were enough for NPC patients.

Our study was limited by its retrospective and single-center nature without external validation of results. Considering that a prospective randomized clinical trial to elucidate the relationship between interval and prognosis in NPC patients may be ethically unacceptable, further prospective or retrospective observational studies based on real-word data from multicenter are needed in the future.

Conclusion

The prolonged interval > 30 days between IC and RT was associated with a high risk of distant failure, and therefore poor survival prognosis for NPC patients receiving IC before RT, especially for patients with advanced N category. Although confounding factors may underlie this relationship, until a causal relationship can be excluded, efforts should be made to avoid prolonging the interval between IC and RT to minimize risk of distant failure and death.

Additional files

Figure S1. Flow diagram of selection of included patients. NPC, nasopharyngeal carcinoma; CRT, chemoradiotherapy; IC, induction chemotherapy; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus. Figure S2. Distribution of events occurring in 158 patients. Figure S3. Subgroup analyses based on N category. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were delineated based on the interval for overall survival (a, b), disease-free survival (c, d), distant metastasis-free survival (e, f) of N0–1 and N2–3 subgroups. Figure S4. Subgroup analyses based on IC cycles. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were delineated based on the interval for overall survival (a, b), disease-free survival (c, d), distant metastasis-free survival (e, f) of IC cycles ≤2 and > 2 subgroups. IC, induction chemotherapy. Figure S5. Subgroup analyses based on concurrent chemotherapy. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were delineated based on the interval for overall survival (a, b), disease-free survival (c, d), distant metastasis-free survival (e, f) of concurrent chemotherapy and no concurrent chemotherapy subgroups. Figure S6. Results of subgroup analyses summarized in forest plot. The HR (95% CI) of the interval for OS, DFS and DMFS in different subgroups and heterogeneity of HR between relative subgroups were shown. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; OS, overall survival; DFS, disease-free survival; DMFS, distant metastasis-free survival; CC, concurrent chemotherapy. (DOCX 632 kb)

Table S1. Baseline characteristics of included and excluded patients. (DOCX 19 kb)

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from Natural Science Foundation of Guang Dong Province (No. 2017A030312003), Health & Medical Collaborative Innovation Project of Guangzhou City, China (201803040003), Innovation Team Development Plan of the Ministry of Education (No. IRT_17R110) and Overseas Expertise Introduction Project for Discipline Innovation (111 Project, B14035).

Availability of data and materials

The key raw data has been uploaded onto the Research Data Deposit (RDD) public platform (http://www.researchdata.org.cn), with the approval RDD number as RDDA2018000783.

Abbreviations

- AJCC/UICC

American Joint Committee on Cancer/International Union against Cancer

- CCI

Charlson comorbidity index

- CI

Confidence interval

- CRT

Chemoradiotherapy

- CTV

Clinical target volume

- DFS

Disease-free survival

- DMFS

Distant metastasis-free survival

- EBV

Epstein-Barr virus

- GTV

Gross tumor volume

- HR

Hazard ratio

- IC

Induction chemotherapy

- IMRT

Intensity modulated radiotherapy

- LRFS

Locoregional recurrence-free survival

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NPC

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- OS

Overall survival

- PET/CT

Positron emission tomography and computed tomography

- PTV

Planning target volume

- REMARK

Reporting Recommendations for Tumor Marker Prognostic Studies

- RT

Radiotherapy

- SPECT

Single photon emission computed tomography

Authors’ contributions

LP collected and analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. JQL collected and analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. CX collected and analysed the data and interpreted the results. XDH collected the data and wrote the manuscript. LLT interpreted the results and reviewed the manuscript. YPC collected the data and reviewed the manuscript. YS reviewed the manuscript. JM designed the study, interpreted the results, and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The clinical research ethics committee of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center approved this study. As this was a retrospective analysis of routine data, we were granted a waiver for written consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Liang Peng, Email: pengliang@sysucc.org.cn.

Jin-Qi Liu, Email: 2690827055@qq.com.

Cheng Xu, Email: xucheng@sysucc.org.cn.

Xiao-Dan Huang, Email: huangxd1@sysucc.org.cn.

Ling-Long Tang, Email: tangll@sysucc.org.cn.

Yu-Pei Chen, Email: chenyup1@sysucc.org.cn.

Ying Sun, Email: sunying@sysucc.org.cn.

Jun Ma, Phone: +86-20-87343469, Email: majun2@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Wei KR, Zheng RS, Zhang SW, Liang ZH, Li ZM, Chen WQ. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma incidence and mortality in China, 2013. Chin J Cancer. 2017;36(1):90. doi: 10.1186/s40880-017-0257-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee AW, Sze WM, Au JS, Leung SF, Leung TW, Chua DT, et al. Treatment results for nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the modern era: the Hong Kong experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61(4):1107–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.07.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mao YP, Xie FY, Liu LZ, Sun Y, Li L, Tang LL, et al. Re-evaluation of 6th edition of AJCC staging system for nasopharyngeal carcinoma and proposed improvement based on magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73(5):1326–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan AT, Gregoire V, Lefebvre JL, Licitra L, Hui EP, Leung SF, et al. Nasopharyngeal cancer: EHNS-ESMO-ESTRO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 7):vii83–vii85. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai SZ, Li WF, Chen L, Luo W, Chen YY, Liu LZ, et al. How does intensity-modulated radiotherapy versus conventional two-dimensional radiotherapy influence the treatment results in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;80(3):661–668. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen YP, Tang LL, Yang Q, Poh SS, Hui EP, Chan ATC, et al. Induction chemotherapy plus concurrent chemoradiotherapy in endemic nasopharyngeal carcinoma: individual patient data pooled analysis of four randomized trials. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(8):1824–1833. doi: 10.1158/078-0432.CCR-17-2656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lefevre JH, Mineur L, Kotti S, Rullier E, Rouanet P, de Chaisemartin C, et al. Effect of interval (7 or 11 weeks) between neoadjuvant Radiochemotherapy and surgery on complete pathologic response in rectal Cancer: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial (GRECCAR-6) J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(31):3773–3780. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.6049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Omarini C, Guaitoli G, Noventa S, Andreotti A, Gambini A, Palma E, et al. Impact of time to surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in operable breast cancer patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43(4):613–618. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao SJ, Corso CD, Wang EH, Blasberg JD, Detterbeck FC, Boffa DJ, et al. Timing of surgery after neoadjuvant Chemoradiation in locally advanced non-small cell lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(2):314–322. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.09.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen YP, Mao YP, Zhang WN, Chen L, Tang LL, Li WF, et al. Prognostic value of wait time in nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with intensity modulated radiotherapy: a propensity matched analysis. Oncotarget. 2016;7(12):14973–14982. doi: 10.8632/oncotarget.7789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li WF, Sun Y, Chen M, Tang LL, Liu LZ, Mao YP, et al. Locoregional extension patterns of nasopharyngeal carcinoma and suggestions for clinical target volume delineation. Chin J Cancer. 2012;31(12):579–587. doi: 10.5732/cjc.012.10095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shao JY, Zhang Y, Li YH, Gao HY, Feng HX, Wu QL, et al. Comparison of Epstein-Barr virus DNA level in plasma, peripheral blood cell and tumor tissue in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2004;24(6):4059–4066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altman DG, McShane LM, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2012;9(5):e1001216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang W, Chen Y, Chen L, Guo R, Zhou G, Tang L, et al. The clinical utility of plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA assays in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: the dawn of a new era?: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 7836 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94(20):e845. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen PC, Yang CC, Wu CJ, Liu WS, Huang WL, Lee CC. Factors predict prolonged wait time and longer duration of radiotherapy in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a multilevel analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109930. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo R, Chen XZ, Chen L, Jiang F, Tang LL, Mao YP, et al. Comorbidity predicts poor prognosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: development and validation of a predictive score model. Radiother Oncol. 2015;114(2):249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peng H, Chen L, Zhang Y, Li WF, Mao YP, Liu X, et al. The Tumour Response to Induction Chemotherapy has Prognostic Value for Long-Term Survival Outcomes after Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24835. doi: 10.1038/srep24835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun Y, Li WF, Chen NY, Zhang N, Hu GQ, Xie FY, et al. Induction chemotherapy plus concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a phase 3, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(11):1509–1520. doi: 10.1016/S470-2045(16)30410-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma BB, Hui EP, Chan AT. Systemic approach to improving treatment outcome in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: current and future directions. Cancer Sci. 2008;99(7):1311–1318. doi: 10.1111/j.49-7006.2008.00836.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vasey PA. “Dose dense” chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15(Suppl 3):226–232. doi: 10.1111/j.525-438.2005.00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crawford J, Dale DC, Lyman GH. Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia: risks, consequences, and new directions for its management. Cancer. 2004;100(2):228–237. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orlandi E, Alfieri S, Simon C, Trama A, Licitra L. Treatment challenges in and outside a network setting: head and neck cancers. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;14(18):30417. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng H, Chen L, Li WF, Zhang Y, Liu LZ, Tian L, et al. Optimize the cycle of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with intensity-modulated radiotherapy: A propensity score matching analysis. Oral Oncol. 2016;62:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Flow diagram of selection of included patients. NPC, nasopharyngeal carcinoma; CRT, chemoradiotherapy; IC, induction chemotherapy; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus. Figure S2. Distribution of events occurring in 158 patients. Figure S3. Subgroup analyses based on N category. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were delineated based on the interval for overall survival (a, b), disease-free survival (c, d), distant metastasis-free survival (e, f) of N0–1 and N2–3 subgroups. Figure S4. Subgroup analyses based on IC cycles. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were delineated based on the interval for overall survival (a, b), disease-free survival (c, d), distant metastasis-free survival (e, f) of IC cycles ≤2 and > 2 subgroups. IC, induction chemotherapy. Figure S5. Subgroup analyses based on concurrent chemotherapy. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were delineated based on the interval for overall survival (a, b), disease-free survival (c, d), distant metastasis-free survival (e, f) of concurrent chemotherapy and no concurrent chemotherapy subgroups. Figure S6. Results of subgroup analyses summarized in forest plot. The HR (95% CI) of the interval for OS, DFS and DMFS in different subgroups and heterogeneity of HR between relative subgroups were shown. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; OS, overall survival; DFS, disease-free survival; DMFS, distant metastasis-free survival; CC, concurrent chemotherapy. (DOCX 632 kb)

Table S1. Baseline characteristics of included and excluded patients. (DOCX 19 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The key raw data has been uploaded onto the Research Data Deposit (RDD) public platform (http://www.researchdata.org.cn), with the approval RDD number as RDDA2018000783.