Abstract

Background

New laparoscopic devices, such as electrothermal bipolar-activated devices (LigaSure™ (LS)) or ultrasonic systems (Harmonic® scalpel (HS)), have been applied recently to bariatric surgery allowing to reduce blood loss and surgical risks. The aim of this study was to retrospectively compare intraoperative performance of HS and LS, postoperative results, and clinical outcomes in a large cohort of patients undergoing LSG.

Methods

Data from 422 morbidly obese patients undergoing LSG in our Bariatric Unit at the Advanced Biomedical Sciences Department of the “Federico II” University of Naples (Italy) between January 2009 and December 2017 were retrospectively analyzed. Subjects were divided into two groups (HS and LS), and operative time, intraoperative complications, and postoperative (within 30 days from surgery) complications were compared. Bleeding from the omentum or from the staple line, use of hemostatic clips, and absorbable hemostat were recorded as intraoperative complications; hemorrhages, abscess formation, gastric leaks, fever, and mortality were considered as postoperative complications.

Results

Statistical analysis showed no difference in terms of baseline demographics between the two cohorts. Operative time (48 ± 9 vs 49 ± 6 min, p=0.646) and the rates of intraoperative and postoperative complications did not significantly differ between groups.

Conclusion

Harmonic® and LigaSure™ are both useful tools in bariatric surgery, and these two advanced power devices are user-friendly and can facilitate surgeon work; from this point of view, the choice of the energy device should be based on the preference of the surgeon and on the hospital costs policy and availability.

1. Introduction

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) was conceived as the first surgical step for high-risk patients undergoing laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) or biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS) [1, 2]. This bariatric procedure has gained popularity because of its relative simplicity and great results shown over the years, both on weight loss- and on obesity-related comorbidities [3–5]. Although LSG is commonly considered a safe and effective procedure, some complications may occur during and after surgery such as bleeding, staple line leaks, and micronutrient deficiencies [6–11].

New laparoscopic devices, such as electrothermal bipolar-activated devices (LigaSure™ (LS)) or ultrasonic systems (Harmonic® scalpel (HS)), have been applied recently to bariatric surgery allowing to reduce blood loss and surgical risks. These instruments, used to achieve an adequate hemostasis and an easier tissue dissection, have become coresponsible of the short learning curve and of technical simplicity of LSG.

LigaSure™ (Valleylab, Boulder, CO, USA) is an electrothermal device which is used to seal vessels up to 7 mm in diameter. Its form of energy denatures collagen and elastin of vessels and connective tissue determining vessel fusion. It is important that a feedback-controlled response system automatically discontinues energy delivery when the seal cycle is complete. Harmonic Ace® (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc.), instead, uses ultrasonic vibration determining effects of cutting, coaptation, coagulation, and cavitation of vessels tissues. It is documented that it produces minimal lateral thermal spread when dissecting near vital structures [12, 13].

The aim of this study was to retrospectively compare intraoperative performance, postoperative results, and clinical outcomes of HS and LS in a large cohort of patients undergoing LSG.

2. Methods

Data from 422 morbidly obese patients undergoing LSG in our Bariatric Unit at the Advanced Biomedical Sciences Department of the “Federico II” University of Naples (Italy) between January 2009 and December 2017 were retrospectively analyzed. Subjects were divided into two groups (HS and LS); baseline demographics, such as gender, age, height, weight, comorbidities, and previous operations were recorded. Operative time and intraoperative and postoperative (within 30 days from surgery) complications were compared. Bleeding from the omentum or from the staple line and use of hemostatic clips and absorbable hemostat were recorded as intraoperative complications; hemorrhages, abscess formation, gastric leaks, fever, and mortality were considered as postoperative complications. Patients were men and women aged between 18 and 65 years with a body mass index (BMI) ranging from 35 to 55 kg/m2. Criteria of exclusion from the study were previous supramesocolic surgery, ASA (American Society of Anesthesiology) score 4, treated or untreated malignancies at any stage, and conversion to open surgery.

The study was approved by our institutional review board, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects before enrollment. All investigations complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (64th WMA General Assembly, Fortaleza, Brazil, October 2013).

2.1. Preoperative Care

All patients underwent a preoperative esophagogastroscopy (EGDS) to rule out gastric lesions, and a pulmonary thromboembolism (PE) prophylaxis was administered according to SICOB (Italian Society of Bariatric Surgery) guidelines [14]. Perioperative antiplatelet drugs administration was managed according to validated criteria [15]. One dose of 2 g ceftriaxone was administered intravenously 10–15 min before the operation for infection prophylaxis. In all cases, surgery started with a laparoscopic approach. All patients had the same protocols for anesthesia and postoperative management.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (Version 20.0 for Windows; SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill, USA). The Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparison between two categories of a categorical variable, and Pearson's chi-square was used in order to evaluate any association between pairs of categorical variables. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.3. Surgical Technique

All operations were performed by the same two experienced bariatric surgeons (Ma. Mu, Ma. Mil).

The choice of the device (LS or HA) used during surgery was based on the availability of our clinic; both surgeons used both devices from the beginning of the learning curve.

Following the preparation of the greater curvature, a gastric sleeve was tailored using a 60 mm linear stapler (Echelon flex 60®, Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Johnson & Johnson©, Somerville NJ, USA) and a 38F bougie. A total of five to seven cartridges were used. Between the closure of the stapler and its firing, a 20 sec interval was observed in any case [16]. A methylene blue test with 80–100 mL of saline solution was routinely performed to evaluate possible leaks. No oversewing of the staple line was performed to prevent bleeding or staple line leaks, but human fibrin sealant (Tisseel™, Baxter® Deerfield, IL, USA) was sprayed along the suture line [17, 18]. The excided stomach was extracted as previously described [19]. In all patients, a nasogastric tube and a drainage tube were positioned at the end of the procedure. The nasogastric tube was removed on postoperative day (POD) 1, and a liquid diet was started on POD 3 and was allowed for 10–15 days under strict nutritionist surveillance [20]. An abdominal CT scan was scheduled if clinical symptoms (fever, tachycardia, leukocytosis, and pain) were present [21]. Patients were routinely discharged on POD 5.

3. Results

During the study period, 422 patients underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity in our institution; 108 (25.6%) were men and 314 (74.4%) were women; two hundred twenty-five of them were operated using LS, and the other 197 were operated using HS.

Statistical analysis showed no difference in terms of age, BMI, comorbidities (diabetes and hypertension), and length of stay between the two cohorts; no differences were found in the number of cartridges used during surgery (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study population.

| LigaSure™ (n=225) | Harmonic Ace® (n=197) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female (n) | 175 | 139 | 0.090 |

| Age (years) | 42.6 ± 10.73 | 41.2 ± 8.26 | 0.131 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 47.2 ± 6.11 | 47.7 ± 5.23 | 0.365 |

| Diabetes (n) | 81 | 77 | 0.513 |

| Hypertension (n) | 67 | 75 | 0.072 |

| Length of stay (days) | 4.8 ± 1.3 | 5.1 ± 2.1 | 0.074 |

| Cartridge used (n) | 6.51 ± 0.79 | 6.56 ± 0.77 | 0.512 |

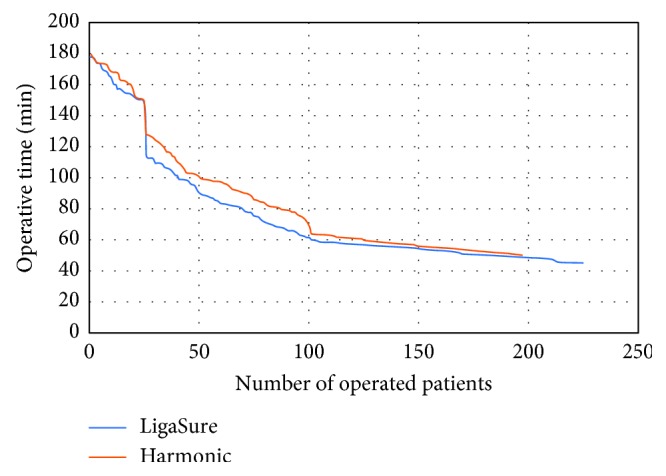

Operative time at the beginning of our learning curve (first 25 cases operated with LS vs first 25 cases operated with HA) did not significantly differ between groups (159 ± 7 vs 161 ± 9 min, p=0.384); the same results were observed when considering operative time in last 25 cases operated with LS vs last 25 cases operated with HA (48 ± 9 vs 49 ± 6 min, p=0.646).

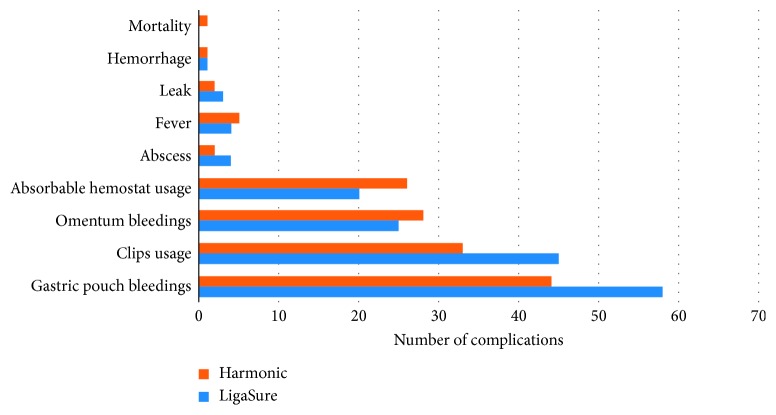

Finally, the rates of intraoperative and postoperative complications and the number of surgical revisions did not significantly differ between groups (Table 2) (Figures 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Intraoperative and perioperative complications of the patients who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy with LigaSure™ and Harmonic Ace®.

| LigaSure™ | Harmonic Ace® | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative complications (n) | |||

| Omentum bleedings | 25 | 28 | 0.337 |

| Staple line bleedings | 58 | 44 | 0.409 |

| Clips | 45 | 33 | 0.391 |

| Absorbable hemostat | 20 | 26 | 0.156 |

| Postoperative complications (n) | |||

| Hemorrhage | 1 | 1 | 0.924 |

| Abscess | 4 | 2 | 0.509 |

| Leak | 3 | 2 | 0.763 |

| Fever | 4 | 5 | 0.589 |

| Mortality | 0 | 1 | 0.284 |

| Complications needing revision (n) | 2 | 1 | 0.584 |

Figure 1.

Intraoperative and postoperative complications occurred with Harmonic® and LigaSure™ in the patients' cohort (within 30 days).

Figure 2.

Differences in operative time between Harmonic® and LigaSure™.

4. Discussion

LSG is usually considered as a restrictive procedure, and even though some studies have speculated about the metabolic effects on gut hormones release, this issue remains controversial [22]. LSG may entail higher operative and perioperative risks in comparison with other purely restrictive procedures [23]; nevertheless in skilled hands, its efficacy remains undisputed, especially in the long term, presenting a very low rate of major complications. [24].

Nowadays, different methods are available to control bleeding during laparoscopic procedures: energy devices, electrocautery, clips, vascular staplers, and intracorporeal sutures. Electrocautery is cost-effective and easy to access, but it offers less hemostatic effect when compared to bipolar or energy‐based vessel-sealing devices (VSDs) and causes more lateral thermal damage in the peripheral tissues [25].

Vessel sealing devices differ in design and in the type of energy used; the first generation of ultrasonic VSDs was able to seal vessels up to 3 mm but currently, technological innovation allowed these instruments to close structures up to 7 mm [26]. Okhunov et al. [27] found there are no bursting pressure failures for the HA and LS up to 9 mm vessels.

In order to choose an adequate device to minimize intraoperative and perioperative surgical complications, we compared two different power devices, which were both widely used in various kinds of surgeries.

Many studies in the literature have compared the effectiveness of these two devices in endocrine, colorectal, and gynaecological surgery, but evidences from randomised studies, particularly in laparoscopic approach, are very limited [28–32].

Previous studies on the topic have shown comparable advantages of the use of LA and HA. Campagnacci et al. [33] found no difference in the duration for colorectal surgery between the two devices, but there was less bleeding with LS. No statistical difference was also detected by Yavuz et al. [34] in a randomised trial with 24 cases of laparoscopic appendicectomy. Rimonda et al. [35] analyzed results from 140 patients (31 right hemicolectomies, 69 left hemicolectomies, and 40 anterior resections of rectum): they concluded that LigaSure and Harmonic are both useful and safe instruments for laparoscopic colorectal surgery with no significant difference in terms of intraoperative/postoperative morbidity and operative time.

About bariatric surgery, Tamis et al. [36], in an RCT on 94 patients who underwent LSG using LS or HA, found no significant differences in operative time and complications and concluded that the choice between these two shears lies with the surgeon's preference.

To the best of our knowledge, this study involves the largest series of patients undergoing LSG in which differences between Harmonic® and LigaSure™ use is analyzed, and the results we obtained failed to show a clear advantage in favor of one of the two devices.

The difference in operative time observed in favor of LigaSure™, although not significant, seems to depend principally on surgical dissecting difficulties observed in some patients treated with HA, but these adverse events did not lead to any clinical consequence in the postoperative course. Moreover, the risk of intraoperative bleeding, the use of hemostatic clips and absorbable hemostat, and the postoperative complication rate were similar in the two groups. By this point of view, all bleedings were managed conservatively except for 2 cases in the LS group and 1 case in the HA group which needed a surgical revision.

The only case of death following surgery has been determined by an acute leak on POD1 which caused a rapidly evolving septic shock.

The main limitation of our study is represented by its retrospective design; furthermore, at the beginning of our experience with LSG, operative time was not reported following the video recording which is currently available. This may have generated some inaccuracy in the evaluation of operative time. In contrast, we included a large number of cases, all of which underwent LSG by the same two surgeons at a single institution, minimizing the possible bias induced by surgeons' expertise.

5. Conclusions

Our findings suggest that Harmonic® and LigaSure™ are both useful in bariatric surgery, and these two advanced power devices are user-friendly and can reduce surgeon work load; from this point of view, the choice of the energy device should be based on the preference of the surgeon and on the hospital cost policy.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Regan J. P., Inabnet W. B., Gagner M., Pomp A. Early experience with two-stage laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass as an alternative in the super-super obese patient. Obesity Surgery. 2003;13(6):861–864. doi: 10.1381/096089203322618669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gagner M., Rogula T. Laparoscopic reoperative sleeve gastrectomy for poor weight loss after biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. Obesity Surgery. 2003;13(4):649–654. doi: 10.1381/096089203322190907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milone M., Sosa Fernandez L. M., Sosa Fernandez L. V., et al. Does bariatric surgery improve assisted reproductive technology outcomes in obese infertile women? Obesity Surgery. 2017;27(8):2106–2112. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2614-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milone M., De Placido G., Musella M., et al. Incidence of successful pregnancy after weight loss interventions in infertile women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Obesity Surgery. 2015;26(2):443–451. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1998-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Musella M., Milone M., Maietta P., et al. Bariatric surgery in elderly patients. A comparison between gastric banding and sleeve gastrectomy with five years of follow up. International Journal of Surgery. 2014;12:S69–S72. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.08.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altieri M. S., Wright B., Peredo A., Pryor A. D. Common weight loss procedures and their complications. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2018;36(3):475–479. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milone M., Di Minno M. N. D., Lupoli R., et al. Wernicke encephalopathy in subjects undergoing restrictive weight loss surgery: a systematic review of literature data. European Eating Disorders Review. 2014;22(4):223–229. doi: 10.1002/erv.2292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galloro G., Ruggiero S., Russo T., et al. Staple-line leak after sleve gastrectomy in obese patients: a hot topic in bariatric surgery. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2015;7(9):843–846. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i9.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galloro G., Magno L., Musella M., Manta R., Zullo A., Forestieri P. A novel dedicated endoscopic stent for staple-line leaks after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a case series. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2014;10(4):607–611. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milone M., Velotti N., Musella M. Wernicke encephalopathy following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy-a call to evaluate thiamine deficiencies after restrictive bariatric procedures. Obesity Surgery. 2018;28(3):852–853. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-3083-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scarano V., Milone M., Di Minno M. N. D., et al. Late micronutrient deficiency and neurological dysfunction after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a case report. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2012;66(5):645–647. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2012.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slakey D. P. Laparoscopic liver resection using a bipolar vessel-sealing device: LigaSure®. HPB. 2008;10(4):253–255. doi: 10.1080/13651820802166880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meurisse M., Defechereux T., Maweja S., Degauque C., Vandelaer M., Hamoir E. Évaluation de l’utilisation du dissecteur ultrasonique Ultracision® en chirurgie thyroïdienne. Étude prospective randomisée. Annales de Chirurgie. 2000;125(5):468–472. doi: 10.1016/s0003-3944(00)00223-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. http://www.sicob.org, 2018.

- 15.Di Minno M. N., Milone M., Mastronardi P., et al. Perioperative handling of antiplatelet drugs. A critical appraisal. Current Drug Targets. 2013;14(8):880–888. doi: 10.2174/1389450111314080008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker R. S., Foote J., Kemmeter P., Brady R., Vroegop T., Serveld M. The science of stapling and leaks. Obesity Surgery. 2004;14(10):1290–1298. doi: 10.1381/0960892042583888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Musella M., Milone M., Bellini M., Leongito M., Guarino R., Milone F. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Do we need to oversew the staple line? Annali Italiani Di Chirurgia. 2011;82(4):273–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Musella M., Milone M., Maietta P., Bianco P., Pisapia A., Gaudioso D. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: efficacy of fibrin sealant in reducing postoperative bleeding. A randomized controlled trial. Updates in Surgery. 2014;66(3):197–201. doi: 10.1007/s13304-014-0257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maietta P., Milone M., Coretti G., et al. Retrieval of the gastric specimen following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Experience on 275 cases. International Journal of Surgery. 2016;28(1):S124–S127. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guida B., Cataldi M., Busetto L., et al. Predictors of fat-free mass loss 1 year after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 2018;41(11):1307–1315. doi: 10.1007/s40618-018-0868-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Musella M., Cantoni V., Green R., et al. Efficacy of postoperative upper gastrointestinal series (UGI) and computed tomography (CT) scan in bariatric surgery: a meta-analysis on 7516 patients. Obesity Surgery. 2018;28(8):2396–2405. doi: 10.1007/s11695-018-3172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Musella M., Di Capua F., D’Armiento M., et al. No difference in ghrelin-producing cell expression in obese versus non-obese stomach: a prospective histopathological case-control study. Obesity Surgery. 2018;28(11):3604–3610. doi: 10.1007/s11695-018-3401-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hutter M. M., Schirmer B. D., Jones D. B., et al. First report from the American College of Surgeons Bariatric Surgery Center Network: laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy has morbidity and effectiveness positioned between the band and the bypass. Annals of Surgery. 2011;254(3):410–420. doi: 10.1097/sla.0b013e31822c9dac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Musella M., Milone M., Gaudioso D., et al. A decade of bariatric surgery. What have we learned? Outcome in 520 patients from a single institution. International Journal of Surgery. 2014;12(1):S183–S188. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirmizi S., Kayaalp C., Karagul S., et al. Comparison of Harmonic scalpel and Ligasure devices in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Videosurgery and Other Miniinvasive Techniques. 2017;1:28–31. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2017.66641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Timm R., Asher R., Tellio K., Welling A. L., Clymer J., Amaral J. Sealing vessels up to 7 mm in diameter solely with ultrasonic technology. Medical Devices: Evidence and Research. 2014;7:263–271. doi: 10.2147/mder.s66848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okhunov Z., Yoon R., Lusch A., et al. Evaluation and comparison of contemporary energy-based surgical vessel sealing devices. Journal of Endourology. 2018;32(4):329–337. doi: 10.1089/end.2017.0596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kendirci M., Şahiner İ. T., Şahiner Y., Güney G. Comparison of effects of vessel-sealing devices and conventional hemorrhoidectomy on postoperative pain and quality of life. Medical Science Monitor. 2018;24:2173–2179. doi: 10.12659/msm.909750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang H. Y., Liu Y. C., Li Y. C., Kuo H. H., Wang C. J. Comparison of three different hemostatic devices in laparoscopic myomectomy. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association. 2018;81(2):178–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang X., Cao J., Yan Y., et al. Comparison of the safety of electrotome, Harmonic scalpel, and LigaSure for management of thyroid surgery. Head and Neck. 2017;39(6):1078–1085. doi: 10.1002/hed.24701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leal C., Ceron R., Rubio V., Unda M. E. Ultrasonic energy (harmonic Ace) versus advanced bipolar energy (ligasure) in a laparoscopic hyterectomies. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology. 2015;22(6):p. S166. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2015.08.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Talha A., Bessa S., Abdel Wahab M. Ligasure, harmonic scalpel versus conventional diathermy in excisional haemorrhoidectomy: a randomized controlled trial. ANZ Journal of Surgery. 2017;87(4):252–256. doi: 10.1111/ans.12838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campagnacci R., de Sanctis A., Baldarelli M., Rimini M., Lezoche G., Guerrieri M. Electrothermal bipolar vessel sealing device vs. ultrasonic coagulating shears in laparoscopic colectomies: a comparative study. Surgical Endoscopy. 2007;21(9):1526–1531. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yavuz A., Bulus H., Taş A., Aydın A. Evaluation of stump pressure in three types of appendectomy: harmonic scalpel, LigaSure, and conventional technique. Journal of Laparoendoscopic and Advanced Surgical Techniques. 2016;26(12):950–953. doi: 10.1089/lap.2015.0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rimonda R., Arezzo A., Garrone C., Allaix M. E., Giraudo G., Morino M. Electrothermal bipolar vessel sealing system vs. harmonic scalpel in colorectal laparoscopic surgery: a prospective, randomized study. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2009;52(4):657–661. doi: 10.1007/dcr.0b013e3181a0a70a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsamis D., Natoudi M., Arapaki A., et al. Using Ligasure™ or Harmonic Ace® in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomies? A prospective randomized study. Obesity Surgery. 2015;25(8):1454–1457. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1551-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.