Abstract

Study Objectives

To examine changes in elementary aged children’s sleep and physical activity during a 1-week and a 3-week school break.

Methods

Sleep and physical activity of elementary children (n = 154, age = 5–9 years, 44.8% female, 65.5% African American) were collected over 7 weeks that included a 1-week break in two schools and a 3-week break in a single school. Mixed regression models estimated sleep and physical activity changes within and between groups (i.e. 1-week vs. 3-weeks) during school and school break weeks.

Results

Compared to school weeks, bed times shifted 72.7 (95% CI = 57.5, 87.9) and 75.4 (95% CI = 58.1, 92.7) minutes later on weekdays during the 1-week and 3-week break, respectively. Wake times shifted 111.6 (95% CI = 94.3, 128.9) and 99.8 (95% CI = 80.5, 119.1) minutes later on weekdays during 1-week and 3-week breaks. On weekdays during the 3-week break, children engaged in 33.1 (95% CI = 14.1, 52.2) more sedentary minutes and −12.2 (−20.2, −4.2) fewer moderate-to-vigorous physical activity minutes/day. No statistically significant changes in children’s sedentary, light, or moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) minutes were observed on weekdays during the 1-week break. Between-group differences in the change in time sedentary (32.1—95% CI = 5.8, 58.4), and moderate-to-vigorous (−13.0—95% CI = −23.9, −2.0) physical activity were observed.

Conclusions

Children’s sleep shifted later on both 1-week and 3-week breaks. Children’s activity changed minimally on weekdays during a 1-week school break and more during a 3-week school break. Displaced sleep and reductions in activity are intervention targets for mitigating unhealthy weight gain during extended breaks from school.

Keywords: overweight, obesity, health, weight

Statement of Significance

Increased obesogenic behaviors on unstructured days including shifting sleep patterns and reduced engagement in physical activity may be leading to accelerated weight gain during extended school breaks. This study examined changes in elementary children’s objectively measured sleep and physical activity during school breaks. Children’s sleep shifted later for children on a 1-week and 3-week school break. However, activity levels of children on a 1-week break from school changed minimally while larger changes were observed for children on a 3-week school break. Changes in sleep and physical activity during school breaks could explain accelerated weight gain and fitness loss during extended breaks from school like summer vacation. Thus, displaced sleep patterns and decreased physical activity are important targets for intervention.

Introduction

The structured days hypothesis suggests that children engage in a greater number of behaviors that lead to increased weight gain on less-structured days (e.g. weekends, spring break, summer vacation) than on more-structured days (e.g. school days) [1]. Increased obesogenic behaviors on unstructured days include increased time spent sedentary, reduced engagement in physical activity, and displaced sleep patterns (i.e. shifting bed and wake times earlier or later). Extended exposure to unstructured environments during the summer may lead to the well-documented phenomenon of accelerated unhealthy weight gain and fitness loss in elementary aged children over summer break from school [2–9].

However, the evidence supporting the structured days hypothesis has mostly examined weekday versus weekend days [10–16]. Few studies have examined behaviors over longer unstructured periods like the summer or holiday breaks. Those studies that have examined behaviors during extended breaks from school have largely relied on self-reported [17–19] and/or between participant comparisons (i.e. different children measured during school and summer) [17, 20–22]. Regardless of these methodological weaknesses, these studies consistently show that children’s sleep shifts later and lasts longer while physical activity levels decrease during breaks from school. Further, studies in adolescents have shown that sleep and physical activity can change in just 2 weeks away from school [19].

Only two small studies, one with data on 14 children and the other with data on 30 children, have employed objective measures and a within participant repeated measures design to explore changes in physical activity during extended school breaks [23, 24]. Both studies found that children were less active during the break from school when compared to activity levels during the school year. One of these studies also examined changes in children’s sleep during break [24]. This study found that children slept for 14.3 more minutes per day during the school break when compared to a school week. However, the small sample size of these studies limits the external validity of the findings. Further, the study that examined sleep did not present changes in children’s bed or wake times, which has been shown to be related to weight status independent of sleep duration [25, 26]. Another study used actigraphy to examine the changes in sleep patterns of 146 adolescents during a 2-week break from school [27]. This study found that bed and wake times shifted later, total sleep time increased, and sleep efficiency decreased during breaks from school. However, given the developmental differences between elementary-aged children and adolescents, generalizing findings from studies in adolescents to elementary aged children may not be appropriate.

Understanding the impact of extended breaks from school on elementary aged children’s obesogenic behaviors can inform strategies to address these unhealthy behaviors particularly during extended breaks from school (e.g. school holidays and during summer) wherein marked weight gain and fitness loss can occur [4, 5]. Identifying which behaviors are changing in negative ways can inform targets for intervention. Alternatively, identifying which behaviors are unaffected by breaks can allow interventionists to avoid costly and ineffective interventions that target extraneous behaviors. Thus, the objective of this natural experiment was to use a within and between participant design to explore changes in elementary children’s sleep and physical activity during school breaks versus regular school schedules and to compare differences in changes between 1-week versus 3-week breaks.

Methods

Participating schools and children

The characteristics of the participating schools and children are presented in Table 1. Three schools in one school district were invited to participate in the study. Schools were selected because one school (i.e. School A) followed a year-round schedule and the two other schools (i.e. School B and C) were match-paired based on student population race/ethnicity and gender, number of students enrolled, age/grade levels served, percentage of students receiving free and reduced lunch, and academic test scores.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participant schools and students

| School | A | B | C | All schools |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| School characteristics | ||||

| Total students | 438 | 456 | 389 | 1283 |

| Percent boys | 53.3 | 60.5 | 49.9 | 54.6 |

| Grades | prek-6 | prek-6 | k-6 | prek-6 |

| Race | ||||

| Percent white | 29.5 | 23.5 | 32.8 | 28.6 |

| Percent black | 63.0 | 67.6 | 57.8 | 62.8 |

| Percent other race | 7.5 | 8.7 | 9.4 | 8.5 |

| Percent free & reduced lunch | 81.0 | 87.0 | 84.0 | 84.0 |

| Type of school calendar | Year round | Traditional | Traditional | N/A |

| Length of school break | 3 weeks | 1 week | 1 week | N/A |

| School rural–urban continuum codes | Rural | Urban | Rural | N/A |

| School start time | 7:40 am | 7:45 am | 7:45 am | N/A |

| School end time | 2:40 pm | 2:40 pm | 2:40 pm | N/A |

| Participant characteristics | ||||

| Boys | ||||

| Number of participants (at least three weekdays and one weekend day of valid wear) | 27 | 23 | 35 | 85 |

| Mean weekdays of valid wear (SD) | 12.8 (4.9) | 9.1 (3.8) | 11.7 (5.2) | 11.5 (4.8) |

| Mean weekend days of valid wear (SD) | 5.5 (2.1) | 3.7 (1.6) | 4.9 (2.1) | 4.9 (2.1) |

| Grade (SD) | 1.7 (1.0) | 1.9 (1.0) | 1.6 (1.0) | 1.7 (1.0) |

| Age (SD) | 7.2 (0.6) | 6.9 (1.2) | 6.9 (1.1) | 7.1 (0.9) |

| Race | ||||

| Percent white | 7.4 | 35.0 | 37.0 | 24.2 |

| Percent black | 92.6 | 65.0 | 26.3 | 65.1 |

| Percent other race | 0.0 | 0.0 | 36.8 | 10.7 |

| Percent free & reduced lunch | 41.9 | 81.8 | 47.9 | 53.5 |

| Mean resting heart rate | 65.7 (5.5) | 67.2 (6.6) | 67.2 (6.1) | 66.5 (6.0) |

| Girls | ||||

| Number of participants (at least three weekdays and one weekend day of valid wear) | 29 | 20 | 20 | 69 |

| Mean weekdays of valid wear (SD) | 11.7 (5.0) | 13.1 (5.6) | 10.8 (4.4) | 11.7 (4.9) |

| Mean weekend days of valid wear (SD) | 4.6 (1.8) | 5.1 (2.1) | 4.1 (1.7) | 4.6 (1.9) |

| Grade (SD) | 1.7 (1.0) | 1.9 (1.0) | 1.7 (1.0) | 1.7 (1.0) |

| Age (SD) | 7.0 (0.4) | 7.0 (1.3) | 7.0 (1.0) | 7.0 (0.8) |

| Race | ||||

| Percent white | 6.9 | 25.0 | 60.0 | 31.7 |

| Percent black | 93.1 | 75.0 | 33.3 | 65.8 |

| Percent other race | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.7 | 2.5 |

| Percent free & reduced lunch | 80.0 | 48.8 | 70.8 | 67.5 |

| Mean resting heart rate | 68.8 (5.0) | 67.4 (4.2) | 68.8 (5.2) | 68.2 (4.7) |

School schedules

The main contrast of interest in the current natural experiment was the type of school schedule that the participating schools followed (i.e. traditional vs. year-round). Traditional schools follow a calendar that condenses the 180-day school year into 9 months, typically late August through May, and takes an extended 3 month, typically June through early August, vacation from school during the summer. Year-round schools follow a 180-day school year as well, but year-round schools spread school days equally throughout the calendar year by taking shorter, more frequent breaks. The year-round school in this study followed a 45 on 15 off schedule. That is, 45 weekdays (i.e. 9 weeks) that children attend school followed by 15 weekdays (i.e. 3 weeks) that children do not attend school. The observation period in this study overlapped with the traditional schools’ spring break (i.e. 1 week of school break) and the year-round school’s 15-day break (i.e. 3 weeks of school break).

Measurement of physical activity and sleep

Physical activity and sleep were measured using a Fitbit Charge 2 (Fitbit Inc., San Francisco, California). Fitbit Charge devices have been shown to provide sleep and heart rate estimates that demonstrate good agreement with polysomnography and electrocardiography, respectively [28–30]. Fitbits were chosen because of this and to minimize participant burden (e.g. ability for family to charge and sync devices at home thus eliminating the need for multiple contacts with the research team to trade out devices over the study duration) over extended wear periods. Each Fitbit was assigned a unique numeric identifier. Researchers created a generic account for each profile prior to providing it to children during their regularly scheduled physical education class. Profiles were linked to Fitabase (San Diego, California) a web-based interface that allows remote access and data download of participants’ Fitbit data.

Measurement of structured program attendance outside of the school day

To examine engagement in structured programs during non-school hours, parents also completed a brief survey on which they reported the number of structured programs that children attended outside of the school day, each month, over the past year. Structured programs were defined as pre-planned, segmented, and adult-supervised compulsory environments. Examples of structured programs included: after-school programs, summer camps, sports programs, and practices, etc.

Procedures

All kindergarten through third-grade students enrolled at the participating schools were invited to participate in the study in the Spring of 2018. Due to a limited number of Fitbits, from the 254 children that consented, a total of 240 were randomly selected to participate in the study. Children received their Fitbit 2 weeks (i.e. year-round school) and 4 weeks (i.e. traditional schools) prior to spring break and wore the Fitbit for eight consecutive weeks. Children were instructed to wear the devices at all times including when they slept, showered/bathed, and swam (i.e. 24-hour wear protocol).

Statistical analyses

Data processing

At the end of the 8-week period, each child’s heart rate and sleep data were downloaded via Fitabase. Data from the first week of wear (i.e. run-in period) were removed prior to processing leaving each child with seven possible weeks (i.e. 49 days) of heart rate and sleep data. Heart rate data (i.e. beats per minute) were downloaded for each second of wear while sleep data were downloaded for each minute of wear. On average a heart rate was sampled every 8.0 (SD = 4.6) seconds of wear. Data processing was informed by the ISCOLE data processing protocols [31].

Sleep data were exported to identify child sleep episodes. Bedtime was determined to be the time that the first minute of a sleep episode began. Wake time was identified as the last minute that a sleep episode was recorded. Sleep midpoint was calculated by identifying the time half way between bedtime and wake time. Time in bed was calculated by subtracting bed time from wake time. Total sleep time was identified as the sum of the minutes that the Fitbit device classified a child as asleep during a sleep episode. Sleep efficiency was calculated by dividing the total sleep time by time in bed. For this paper, only nocturnal sleep was considered. Nocturnal sleep was considered sleep bed times that occurred between 5 pm and 6 am and lasted for greater than 240 minutes [32]. If sleep segments were separated by less than 20 minutes they were considered one continuous sleep segment [31].

To distill the heart rate data into activity intensity levels each child’s resting heart rate was identified as the average of the lowest 10-minute heart rate beats-per-minute for each day. This is consistent with previous studies collecting heart rate over a full day [33–36]. Resting heart rates were calculated for each child each day of wear. Resting heart rates that were above the 95th (90 bpm), or below the 5th (50 bpm) percentile were considered implausible and were replaced with the closest day that the child had a plausible resting heart rate. Heart rates were distilled into activity intensity levels based on percent heart rate reserve (HRR). Consistent with previous research 0.0–19.9% of HRR was considered sedentary, 20.0%–49.9% of HRR was considered light physical activity, and ≥50.0% was considered moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) [37, 38]. Percent HRR was calculating using the following formula . Since a maximal exercise test was not conducted, 197 beats per minute was used as the maximum heart rate for all children [39]. Sleep episode data were mapped onto a child’s physical activity data to determine sleep and wake times. A day with at least 10 hours of waking wear was considered as a valid day of physical activity [31]. Valid cases were defined as children that had at least 4 days of wear (three weekdays and one weekend day) with ≥10 hours of waking wear time during both break and school weeks. Data were then distilled into the amount of waking time children spent sedentary, in light physical activity, and in MVPA on each day.

Analytic plan

All analyses were completed in May of 2018 in Stata (v14.2, College Station, Texas). Before primary analyses, descriptive means and SDs of school and child characteristics were examined. A two-step analytic plan was undertaken.

First multi-level mixed effect linear regressions with days nested within children and assuming an autoregressive structure for residual errors estimated the difference in mean bed time, wake time, sleep midpoint, time in bed, total sleep time, sleep efficiency, daily minutes sedentary, in light physical activity, and in MVPA on school weeks versus break weeks. Sleep variables and activity minutes were the dependent variables and break was the independent variable. Separate models were estimated for weekend versus weekdays and each sleep and activity variable for both the 1-week break group and the 3-week break group.

Second, to test if the differing school break lengths (i.e. 1 week vs. 3 weeks) were associated differently with children’s sleep and activity, multi-level mixed effect linear regressions with the same nesting structure identified above and assuming an autoregressive structure for residual errors were estimated. These models included sleep variables and activity minutes as the independent variable, a dichotomous break type variable (i.e. 3-week = 1, 1-week = 0), a dichotomous week variable (school week = 1, school break week = 0), and a week by break type interaction variable. All models in step one and two included grade, gender, and day as covariates. Models with a physical activity independent variable included total wear time as an additional covariate. Finally, to examine where differences in sedentary behavior and physical activity occurred the mean minutes of sedentary time, light physical activity, and MVPA was calculated for each hour during school weekday and break weekday.

Results

Descriptive characteristics of the participating schools and children are presented in Table 1. Sleep and activity outcomes are presented in Table 2. There were no statistically significant between-group differences in sleep variables during school weeks on weekend or weekdays. The parents of children attending the schools that provided a 1-week break reported their children participating in a mean of 4.1 (SD = 7.0) structured programs outside the school day over the last 12 months. The parents of children attending the school that provided a 3-week break reported their children participating in a mean of 7.4 (SD = 9.0) structured programs. Types of programs reported included, after-school programs, extramural sports programs, and before school activity clubs.

Table 2.

Changes in sleep and physical activity minutes during school breaks within and between school conditions

| Weekday | Weekend day | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Break length | Schoola | Breaka | Withina | Betweenb | Schoola | Breaka | Withina | Betweenb | |||||

| Sleep | ∆ | 95% CI | ∆ | 95% CI | ∆ | 95% CI | ∆ | 95% CI | |||||

| Bedtime | 1-week | 22:19.48 | 23:33.00 | 72.7 | (57.5, 87.9) | 3.3 | (−19.5, 26.1) | 22:46.48 | 23:09.36 | 22.7 | (2.8, 42.7) | 19.0 | (−15.5, 53.6) |

| 3-week | 22:41.24 | 23:57.00 | 75.4 | (58.1, 92.7) | 23:04.48 | 23:45.36 | 40.5 | (10.6, 70.4) | |||||

| Waketime | 1-week | 6:40.12 | 8:31.48 | 111.6 | (94.3, 128.9) | −11.1 | (−36.8, 14.6) | 7:38.24 | 8:13.12 | 34.7 | (14.5, 54.9) | 11.5 | (−23.5, 46.5) |

| 3-week | 7:04.48 | 8:45.00 | 99.8 | (80.5, 119.1) | 7:53.24 | 8:39.36 | 46.2 | (15.9, 76.4) | |||||

| Midpoint | 1-week | 2:31.48 | 4:03.00 | 91.3 | (78.8, 103.8) | −3.4 | (−22.2, 15.4) | 3:13.12 | 3:40.48 | 27.4 | (11.8, 43.1) | 14.5 | (−11.7, 40.7) |

| 3-week | 3:00.00 | 4:27.4 | 87.5 | (73.2, 101.8) | 3:31.48 | 4:13.48 | 42.4 | (20.7, 64.1) | |||||

| Time in bed | 1-week | 486.7 | 529.7 | 43.0 | (30.6, 55.3) | −14.8 | (−31.8, 2.2) | 522.3 | 519.8 | −2.5 | (−21.7, 16.6) | −5.2 | (−34.8, 24.4) |

| 3-week | 483.2 | 512.2 | 29.0 | (17.2, 40.7) | 518.1 | 509.2 | −9.0 | (−31.1, 13.2) | |||||

| Total sleep time | 1-week | 456.0 | 494.2 | 38.2 | (26.5, 49.9) | −14.1 | (−30.1, 2.0) | 489.5 | 488.0 | −1.5 | (−19.4, 16.4) | −8.1 | (−35.9, 19.6) |

| 3-week | 453.3 | 478.0 | 24.8 | (13.7, 35.8) | 488.1 | 477.2 | −10.9 | (−31.9, 10.2) | |||||

| Sleep efficiency | 1-week | 93.9 | 93.4 | −0.5 | (−1.0, 0.0) | 0.0 | (−0.7, 0.7) | 93.9 | 94.2 | 0.3 | (−0.2, 0.8) | −0.6 | (−1.5, 0.2) |

| 3-week | 93.9 | 93.4 | −0.6 | (−1.0, −0.1) | 94.1 | 93.8 | −0.4 | (−1.0, 0.3) | |||||

| Physical activity | |||||||||||||

| Sedentary | 1-week | 483.6 | 482.3 | −1.3 | (−19.9, 17.3) | 32.1 | (5.8, 58.4) | 504.0 | 530.0 | 26.0 | (−1.8, 53.8) | −18.8 | (−58.2, 20.6) |

| 3-week | 445.9 | 479.1 | 33.1 | (14.1, 52.2) | 456.3 | 461.4 | 5.0 | (−22.8, 32.8) | |||||

| Light physical activity | 1-week | 193.6 | 192.8 | −0.9 | (−14.6, 12.9) | −18.5 | (−37.7, 0.8) | 173.8 | 163.7 | −10.2 | (−28.6, 8.3) | 14.8 | (−12.0, 41.7) |

| 3-week | 214.5 | 193.9 | −20.7 | (−34.5, −6.9) | 200.5 | 206.7 | 6.2 | (−13.3, 25.7) | |||||

| MVPA | 1-week | 65.7 | 67.8 | 2.0 | (−5.6, 9.7) | −13.0 | (−23.9, −2.0) | 65.3 | 49.0 | −16.2 | (−29.1, −3.4) | 4.2 | (−14.2, 22.6) |

| 3-week | 83.3 | 71.2 | −12.2 | (−20.2, −4.2) | 85.7 | 74.0 | −11.7 | (−24.8, 1.5) | |||||

All models controlled for gender, grade, and weekday; PA models controlled for total wear time additionally. Statistically significant differences are bolded.

aModel implied estimates from regression model restricted to each group with condition (i.e. school vs. break) variable.

bModel implied estimates from regression model with group (year-round vs. traditional), condition (i.e. school vs. break), and group-by-condition variables.

For weekdays, bed times during break shifted 72.7 (95% CI = 57.5, 87.9) and 75.4 (95% CI = 58.1, 92.7) minutes later for children on a 1-week and 3-week break, respectively. Wake times also shifted 111.6 (95% CI = 94.3, 128.9) and 99.8 (95% CI = 80.5, 119.1) minutes later for children on a 1-week and 3-week break, respectively. The shift in bed and wake times affected midpoint of sleep similarly with midpoints shifting 91.3 (95% CI = 78.8, 103.8) and 87.5 (95% CI = 73.2, 101.8) minutes later for children on a 1-week and 3-week break, respectively.

There was also an increase in time in bed and total sleep time for both children on a 1-week and 3-week break. Children on a 1-week break spent 43.0 (95% CI = 30.6, 55.3) more minutes in bed and slept for 38.2 (95% CI = 26.5, 49.9) more minutes during breaks from school. Similarly, children on a 3-week break spent 29.0 (95% CI = 17.2, 40.7) more minutes in bed and slept for 24.8 (95% CI = 13.7, 35.8) more minutes during breaks from school.

There was a −0.5% (95% CI = −1.0%, 0.0%) and −0.6% (95% CI = −1.0%, −0.1%) reduction in sleep efficiency during breaks from school in children receiving a 1- and 3-week break, respectively. No between-group (1-week vs. 3-week) comparisons for weekday sleep variables reached statistical significance during weekdays.

For weekend days, children on a 1- and 3-week break from school went to bed 22.7 (95% CI = 2.8, 42.7) and 40.5 (95% CI = 10.6, 70.4) minutes later than weekend days on school weeks, respectively. Children on a 1-week and 3-week break woke up 34.7 (95% CI = 14.5, 54.9) and 46.2 (95% CI = 15.9, 76.4) minutes later, respectively. Similarly, the midpoint of sleep for children on a 1-week and 3-week break shifted later by 27.4 (95% CI = 11.8, 43.1) and 42.4 (95% CI = 20.7, 64.1) minutes, respectively. No other between (1-week vs. 3-week) or within group difference reached statistical significance on weekend days.

For weekday physical activity, minutes spent sedentary, in light physical activity, or in MVPA were not statistically significantly different during break weekdays when compared to school weekdays in children receiving a 1-week break. For children receiving a 3-week break, weekday sedentary increased by 33.1 (95% CI = 14.1, 52.2) minutes on break weeks when compared to school weeks. Weekday light physical activity and MVPA also decreased by −20.7 (95% CI = −34.5, −6.9) and −13.0 (95% CI = −20.2, −4.2) minutes, respectively, for children on a 3-week break. Further, children receiving a 3-week break increased sedentary by 32.1 (95% CI = 5.8, 58.4) more minutes on break weekdays than children receiving a 1-week break. Children on a 3-week break also reduced weekday MVPA by −13.0 (95% CI = −23.9, −2.0) more minutes than children on a 1-week break.

For physical activity on weekends, children receiving a 1-week break reduced MVPA by −16.2 (95% CI = −29.1, −3.4) minutes on break when compared to school. No other between (1-week vs. 3-week) or within group difference reached statistical significance on weekend days.

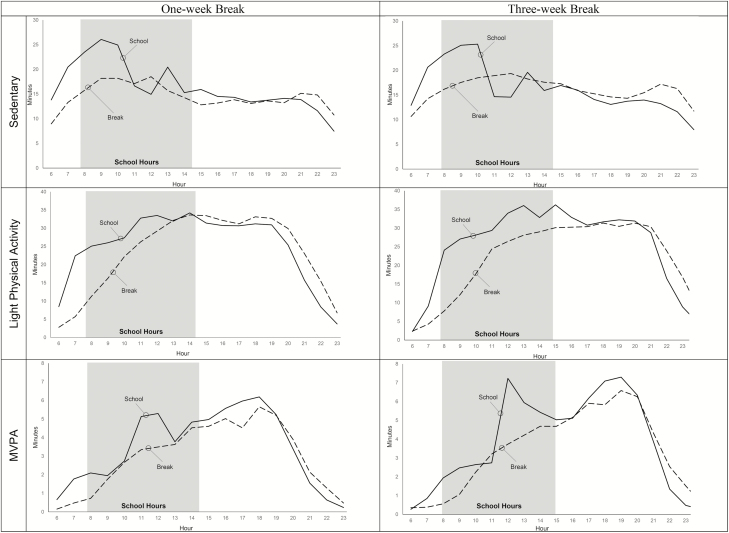

Figure 1 illustrates the mean hourly accumulation of sedentary, light physical activity, and MVPA for children receiving a 1-week versus 3-week break during a school weekday and a break weekday. For children receiving a 1-week and 3-week break during a school weekday the most sedentary minutes per hour were accumulated prior 11:00 am and then slowly declined throughout the rest of the day. This is contrary to break weekdays for children in both groups where sedentary minutes accumulated per hour stayed relatively stable throughout the day. For children receiving a 1-week and 3-week break from school it appears that more light physical activity per hour was accumulated throughout the morning and early afternoon (i.e. school hours) during school days when compared to break days. Accumulation of MVPA per hour was greater on school days when compared to break days early in the morning, around noon, and in the evening, for both groups of children.

Figure 1.

Minutes of sedentary, light physical activity (LPA), and MVPA accumulated by hour on school and break days.

Discussion

This natural experiment evaluated the impact of a 1-week and 3-week break from school on elementary aged children’s sleep and physical activity. Further, this study explored if there were differences in changes in sleep and physical activity between children that received a 1-week and 3-week break from school. The results indicate that during breaks children shifted bed and wake times by more than 1 hour on a 1-week and 3-week break. Further, this study showed that the children slept for approximately 20 to 30 minutes more during breaks from school. Sleep changes during break weekdays seemed to be similar for children that received a 1-week or 3-week break from school. For children that received a 3-week break, weekday sedentary time increased while light physical activity and MVPA decreased. These same trends were not observed in children who received a 1-week break. Thus, a 1-week break from school may not have the same impact on children’s physical activity as a 3-week break.

The duration of sleep of the participating children, on school and break nights, was less than the 9–11 hours that has been recommended for children ages 5–9 years [40]. Further, children slept more on weekends and on breaks from school. This finding is consistent with previous studies in adolescents that have shown children sleep less on school nights [18]. The authors of this study hypothesized that the adolescents were sleeping longer on breaks from school in order to compensate for restricted sleep on school nights. Data from this study suggests that something similar may be occurring for elementary aged children. It is important to note that short sleep duration in children has been associated with obesity and other health risks, including diabetes, mood disorders, and poor academic performance. In this study, short sleep on school nights was largely a function of bedtimes, which were later than average for children of elementary age [12, 41]. While school was in-session, the children delayed their weekend bedtimes by an additional 20 to 30 minutes. These findings could be important as several studies have shown that, independent of sleep duration, children with later bed and wake times are more likely to be overweight or obese [25, 42–44]. The reason for this relationship remains unclear, but at least one study in adolescents found that later bed times were associated with increased daily energy intake and screen use [26]. The authors speculated that later bed times lead to more time sedentary in front of a screen later in evenings, which may lead to increased snacking. Another study demonstrated that children who went to bed and woke later engaged in less MVPA and more screen time than children that went to bed and woke earlier [25]. Later wake times may also increase the likelihood that children and adolescents skip breakfast, which has been associated with increased risk for overweight and obesity in elementary aged children [45] and adolescents [46].

The finding that children shifted weekday sleep later during breaks from school (mid-sleep delay of ~ 90 minutes) is consistent with the structured days hypothesis, which postulates that parents will regulate their children’s sleep (i.e. bed and wake times) on nights/mornings prior to a more-structured day [1]. At least one study in preadolescent children has shown that delaying and extending sleep on free-day versus school days, or social jetlag, is related to a variety of markers of adiposity, while sleep duration was not associated with adiposity [47]. Thus, even though children may be compensating for lost sleep during break nights by sleeping 20 to 30 minutes longer than on school nights the large shifts to later bed and wake times during school breaks may be counteracting the benefit of increased sleep duration. Further changes in sleep for children receiving a 1-week or 3-week break were similar, indicating that children’s sleep shifts later no matter the break length.

This study demonstrated that minutes sedentary increased by 33.1 minutes while light physical activity and MVPA decreased by −20.7 and −12.2 minutes on weekdays during a 3-week break from school. This finding is also consistent with the structured days hypothesis that posits children engage in less physical activity on less structured days when compared to more-structured days. These same patterns were not observed on weekdays for children during the 1-week break from school. This finding suggests that a 1-week break from school may not be sufficient to meaningfully impact children’s weekday activity levels. However, a 3-week break may be enough time to reduce children’s activity.

It is important to note that children who received a 3-week break engaged in more light physical activity and MVPA and less sedentary time on weekdays and weekend days during school weeks than children who received a 1-week break. While it is not clear why this was the case there are at least two possible reasons for this. First, the school that provided children with a 3-week break had 60-minute physical education lessons while the schools that provided children with a 1-week break had 40-minute physical education lessons. Extra time during physical education may have lead accumulation of more MVPA. Second, the parents of children attending the school providing a 3-week break reported that their children participated in more-structured programs outside of the school day than parents of children attending the school providing a 1-week break (7.4 vs. 3.1). Structured programs outside of the school day like after-school and sports programs have the potential to provide children with more physical activity on school week and weekend days. The fact that children at the school providing a 3-week break engaged in more of these activities may partially explain differences in activity levels during school weeks.

On break weekend days children’s sleep shifted later and, excepting light physical activity for children on a 3-week break, accumulation of physical activity decreased while minutes sedentary increased. However, most of these differences were not statistically significant, and the magnitude of these differences was consistently smaller than break weekday versus school weekday differences. This finding is also consistent with the structured days hypothesis. Weekend days are typically less structured than weekdays due to the absence of school. Therefore, according to the structured days hypothesis, children should engage in less physical activity and sleep should shift later. This pattern is evident in our data when examining weekend days versus weekdays on school weeks. This pattern is consistent with a large body of literature showing that children are typically less active and more sedentary on weekend days compared to weekdays [1]. Thus, it is not surprising that the magnitude of the shifts in sleep and physical activity on break weekend days was typically smaller than the shifts in sleep and physical activity on weekdays.

An interesting, and potentially important, pattern of light and MVPA accumulation was evident in the hourly activity data. Activity accumulation during the hours (i.e. 7:45 am to 2:30 pm) of school operation differed on school weekdays compared to break weekdays. That is, children’s hourly accumulation of light and MVPA was greater during school hours on school weekdays when compared to break weekdays. However, hourly activity accumulation in the hours after school ended on school weekdays compared to break weekdays was similar. This finding supports the structured days hypothesis in that the structured and compulsory environment in which children find themselves during the school day leads to more physical activity. Conversely, when school is released, and children find themselves in less structured environments activity accumulation is lower. Thus, interventions that target increasing physical activity accumulation during the school day may be misplaced. Rather, interventions might be more effective if they target activity outside of school hours and during school breaks.

Identifying the effect of varying break lengths on children’s sleep and physical activity is critical for addressing accelerated summer weight gain and fitness loss. A growing body of literature has shown that children’s weight gain accelerates during the summer while fitness declines [2–9, 48]. The structured days hypothesis posits that children engage in more negative obesogenic behaviors on unstructured days like spring break or summer vacation. Thus, over the summer children engage in extended periods of detrimental obesogenic behaviors. However, it is unclear how quickly children’s behaviors deteriorate. This study begins to fill that gap by showing that sleep behaviors change in as little as 1 week while it may take 3 weeks for physical activity behaviors to shift. This information is critical for researchers, public health professionals, and policy makers as they attempt to design interventions to address unhealthy obesogenic behaviors during summer.

This study has several strengths. First, this study used a within-participant repeated measures design to examine changes in sleep and physical activity during breaks from school. This addressed a serious limitation of previous studies examining obesogenic behaviors on school breaks as many used between participant designs [21, 49, 50]. Second, continuous data were collected over an 8-week period with children providing 16.4 days of valid data on average. This is four times the amount of data typically captured in physical activity studies that seek to capture three weekday and one weekend day of data [51], and is more than 10 days which some studies suggest are the minimum number of valid days necessary to reliably assess physical activity [52].

However, there are also limitations of the current study that must be considered when interpreting the data. First, data were collected in three schools that served children that were mostly black and from low-income households. Thus, results from this study may not generalize to other populations of interest. Further, only 63.8% of our recruited sample were considered valid cases. Thus, it is possible that there was some selection bias in our sample. Second, Fitbit has not been used as extensively in sleep and physical activity research as other objective measures of sleep like actigraphy and polysomnography (i.e. considered to be the gold-standard for sleep assessment). Nevertheless, Fitbit measures of sleep and heart rate have been found to have good agreement with polysomnography assessment of sleep and electrocardiography assessment of heart rate [28–30]. Fitbits were chosen because of this and to minimize participant burden (e.g. ability for family to charge and sync devices at home thus eliminating the need for multiple contacts with the research team over the study duration) over extended wear periods. Third, while we did examine within participant changes in sleep and physical activity during breaks from school versus during school, differences in changes of sleep and physical activity between 1-week and 3-week breaks were based upon between-group comparisons. Thus, there is a possibility that break length was not the mechanism driving differences in changes.

While this study adds to the growing literature examining changes in obesogenic behaviors on structured versus less-structured days there is much work that still needs to be done. Future, studies that examine within-participant changes in sleep and physical activity over spring break and during an extended break like summer break are warranted. Further, seasonality has been shown to affect timing and length of sleep in addition to physical activity levels [22, 53]. Thus, the intersection of seasonality and school breaks should be examined. Also, while this study is one of the first to examine changes in sleep and physical activity over extended school breaks it did not examine changes in behaviors during the summer. This is an important gap in current literature that needs to be addressed in future studies. There is also a lack of studies that examine changes in obesogenic behaviors like physical activity, sleep, and diet in adolescents. Finally, there is also a dearth of studies examining changes in the entire spectrum of obesogenic behaviors (i.e. sleep, physical activity, diet, screen time, sedentary behaviors).

This study is one of the first to examine the association of school breaks of different lengths with children’s objectively measured physical activity and sleep. Children’s sleep shifted later for both the 1-week and 3-week school break. Children’s activity levels changed minimally during a 1-week school break. However, larger changes were observed for children on a 3-week school break. Changes in physical activity and sleep during school breaks could help to explain accelerated weight gain and fitness loss during extended breaks from school like summer vacation.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21HD095164. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Institution where work was performed: University of South Carolina.

References

- 1. Brazendale K, et al. . Understanding differences between summer vs. school obesogenic behaviors of children: the structured days hypothesis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sallis JF, et al. . The effects of a 2-year physical education program (SPARK) on physical activity and fitness in elementary school students. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(8):1328–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. von Hippel PT, et al. . The effect of school on overweight in childhood: gain in body mass index during the school year and during summer vacation. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(4):696–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. von Hippel PT, et al. . From kindergarten through second grade, U.S. Children’s obesity prevalence grows only during summer vacations. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24(11):2296–2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moreno JP, et al. . Changes in weight over the school year and summer vacation: results of a 5-year longitudinal study. J Sch Health. 2013;83(7):473–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moreno JP, et al. . Seasonal variability in weight change during elementary school. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23(2):422–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen TA, et al. . Obesity status trajectory groups among elementary school children. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fu Y, et al. . Effect of a 12-week summer break on school day physical activity and health-related fitness in low-income children from CSPAP schools. J Environ Public Health. 2017;2017:9760817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rodriguez AX, et al. . Association between the summer season and body fatness and aerobic fitness among Hispanic children. J Sch Health. 2014;84(4):233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Blader JC, et al. . Sleep problems of elementary school children. A community survey. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151(5):473–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Spilsbury JC, et al. . Sleep behavior in an urban US sample of school-aged children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(10): 988–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Snell EK, et al. . Sleep and the body mass index and overweight status of children and adolescents. Child Dev. 2007;78(1):309–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Spruyt K, et al. . Sleep duration, sleep regularity, body weight, and metabolic homeostasis in school-aged children. Pediatrics. 2011;127(2):e345–e352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stevens J, et al. . Design of the Trial of Activity in Adolescent Girls (TAAG). Contemp Clin Trials. 2005;26(2):223–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Treuth MS, et al. . Relations of parental obesity status to physical activity and fitness of prepubertal girls. Pediatrics. 2000;106(4):E49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Treuth MS, et al. . Weekend and weekday patterns of physical activity in overweight and normal-weight adolescent girls. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15(7):1782–1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Staiano AE, et al. . School term vs. school holiday: associations with children’s physical activity, screen-time, diet and sleep. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(8):8861–8870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wing YK, et al. . The effect of weekend and holiday sleep compensation on childhood overweight and obesity. Pediatrics. 2009;124(5):e994–e1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Agostini A, et al. . Changes in growth and sleep across school nights, weekends and a winter holiday period in two Australian schools. Chronobiol Int. 2018;35(5):1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang YC, et al. . Weight-related behaviors when children are in school versus on summer breaks: does income matter? J Sch Health. 2015;85(7):458–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lanningham-Foster L, et al. . Changing the school environment to increase physical activity in children. Obesity. 2008;16(8):1849–1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nixon GM, et al. . Short sleep duration in middle childhood: risk factors and consequences. Sleep. 2008;31(1):71–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McCue MC, et al. . Examination of changes in youth diet and physical activity over the summer vacation period. Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice. 2013;11(1):8. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brazendale K, et al. . Understanding differences between summer vs. school obesogenic behaviors of children: The Structured Days Hypothesis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Olds TS, et al. . Sleep duration or bedtime? Exploring the relationship between sleep habits and weight status and activity patterns. Sleep. 2011;34(10):1299–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Adamo KB, et al. . Later bedtime is associated with greater daily energy intake and screen time in obese adolescents independent of sleep duration. J Sleep Disord Ther. 2013;2(126):2167-0277.1000126. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bei B, et al. . Actigraphy-assessed sleep during school and vacation periods: a naturalistic study of restricted and extended sleep opportunities in adolescents. J Sleep Res. 2014;23(1):107–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. de Zambotti M, et al. . Measures of sleep and cardiac functioning during sleep using a multi-sensory commercially-available wristband in adolescents. Physiol Behav. 2016;158: 143–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liang Z, et al. . Validity of consumer activity wristbands and wearable EEG for measuring overall sleep parameters and sleep structure in free-living conditions. J Healthc Inform Res. 2018;2(1–2):152–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. de Zambotti M, et al. . A validation study of Fitbit Charge 2™ compared with polysomnography in adults. Chronobiol Int. 2018;35(4):465–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tudor-Locke C, et al. ; ISCOLE Research Group. Improving wear time compliance with a 24-hour waist-worn accelerometer protocol in the International Study of Childhood Obesity, Lifestyle and the Environment (ISCOLE). Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Acebo C, et al. . Estimating sleep patterns with activity monitoring in children and adolescents: how many nights are necessary for reliable measures? Sleep. 1999;22(1): 95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Welk GJ, et al. . The validity of the Tritrac-R3D Activity Monitor for the assessment of physical activity in children. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1995;66(3):202–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sallis JF, et al. . The Caltrac accelerometer as a physical activity monitor for school-age children. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1990;22(5):698–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Janz KF. Validation of the CSA accelerometer for assessing children’s physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26(3):369–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Simons-Morton BG, et al. . Validity of the physical activity interview and Caltrac with preadolescent children. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1994;65(1):84–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chandler JL, et al. . Classification of physical activity intensities using a wrist-worn accelerometer in 8-12-year-old children. Pediatr Obes. 2016;11(2):120–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gavarry O, et al. . Continuous heart rate monitoring over 1 week in teenagers aged 11-16 years. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1998;77(1-2):125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Der Cammen-van Zijp V, et al. . Exercise capacity in Dutch children: new reference values for the Bruce treadmill protocol. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20(1):e130–e136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. National Sleep Foundation. National Sleep Foundation Recommends New Sleep Times.2018. https:/sleepfoundation.org/press-release/national-sleep-foundation-recommends-new-sleep-times/page/0/1. Accessed October 28, 2018.

- 41. Galland BC, et al. . Establishing normal values for pediatric nighttime sleep measured by actigraphy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep. 2018;41(4):zsy017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Golley RK, et al. . Sleep duration or bedtime? Exploring the association between sleep timing behaviour, diet and BMI in children and adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37(4):546–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jarrin DC, et al. . Beyond sleep duration: distinct sleep dimensions are associated with obesity in children and adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37(4):552–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Arora T, et al. . Associations among late chronotype, body mass index and dietary behaviors in young adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond). 2015;39(1):39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Okada C, et al. . Association between skipping breakfast in parents and children and childhood overweight/obesity among children: a nationwide 10.5-year prospective study in Japan. Int J Obes. 2018;42:1724–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Keski-Rahkonen A, et al. . Breakfast skipping and health-compromising behaviors in adolescents and adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57(7):842–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Stoner L, et al. . Sleep and adiposity in preadolescent children: the importance of social jetlag. Child Obes. 2018;14(3):158–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Park KS, et al. . Effects of summer school participation and psychosocial outcomes on changes in body composition and physical fitness during summer break. J Exerc Nutrition Biochem. 2015;19(2):81–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang YC, et al. . Weight-related behaviors when children are in school versus on summer breaks: does income matter? J Sch Health. 2015;85(7):458–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Staiano AE, et al. . School term vs. school holiday: associations with children’s physical activity, screen-time, diet and sleep. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(8): 8861–8870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mattocks C, et al. . Use of accelerometers in a large field-based study of children: protocols, design issues, and effects on precision. J Phys Act Health. 2008;5 (Suppl 1):S98–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Barreira TV, et al. . Reliability of accelerometer-determined physical activity and sedentary behavior in school-aged children: a 12-country study. Int J Obes Suppl. 2015;5(Suppl 2):S29–S35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Carson V, et al. . Seasonal variation in physical activity among children and adolescents: a review. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2010;22(1):81–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]