Abstract

Macrophage fusion that leads to osteoclast formation is one of the most important examples of cell–cell fusion in development, tissue homoeostasis and immune response. Protein machinery that fuses macrophages remains to be identified. In the present study, we explored the fusion stage of osteoclast formation for RAW macrophage-like murine cells and for macrophages derived from human monocytes. To uncouple fusion from the preceding differentiation processes, we accumulated fusion-committed cells in the presence of LPC (lysophosphatidylcholine) that reversibly blocks membrane merger. After 16 h, we removed LPC and observed cell fusion events that would normally develop within 16 h develop instead within 30–90 min. Thus, whereas osteoclastogenesis, generally, takes several days, our approach allowed us to focus on an hour in which we observe robust fusion between the cells. Complementing syncytium formation assay with a novel membrane merger assay let us study the synchronized fusion events downstream of a local merger between two plasma membranes, but before expansion of nascent membrane connections and complete unification of the cells. We found that the expansion of membrane connections detected as a growth of multinucleated osteoclasts depends on dynamin activity. In contrast, a merger between the plasma membranes of the two cells was not affected by inhibitors of dynamin GTPase. Thus dynamin that was recently found to control late stages of myoblast fusion also controls late stages of macrophage fusion, revealing an intriguing conserved mechanistic motif shared by diverse cell– cell fusion processes.

Keywords: cell fusion, dynamin, fusion pore expansion, lysophosphatidylcholine, osteoclast formation, syncytium formation

INTRODUCTION

Formation of a multinucleated cell by fusion of two or more mononucleated cells is one of the most important processes in the life of multicellular organisms. Cells fuse in fertilization, in placentogenesis, in inflammation, in development and in regeneration of muscles and bones [1,2]. Our bones are constantly remodelled by the co-ordinated activity of bone-forming and bone-resorbing cells [3,4]. Osteoclasts, multinucleated giant cells responsible for bone resorption in healthy animals and in metabolic, degenerative and neoplastic bone disorders, are formed by fusion between the cells of the monocyte/macrophage haemopoietic lineage (‘macrophages’). Although this fusion process is essential for the bone-resorbing activity of osteoclasts and thus for bone homoeostasis [5,6], little is known about proteins that mediate the cell-fusion stage of osteoclastogenesis. One of the key challenges in exploring molecular mechanisms of this fusion process is to uncouple fusion from the complex multistep processes that prepare the cells for fusion and take several days. M-CSF (macrophage colony-stimulating factor) stimulates proliferation of bone marrow myeloid progenitor cells. RANKL [receptor activator for NF-κB (nuclear factor κB) ligand] triggers the differentiation of these cells to mononucleated osteoclast precursors. Differentiation and migration that brings osteoclasts into pre-fusion contacts take days and depend on many different intracellular and extracellular proteins. A number of proteins including DC-STAMP (dendritic-cell-specific transmembrane protein) [7], OC-STAMP (osteoclast stimulatory transmembrane protein) [8], purinergic receptors [9,10], syncytin [11], PTP (protein tyrosine phosphatase)-PEST [12] and an intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel [13] have been suggested to mediate or regulate macrophage fusion downstream of osteoclast differentiation. Intriguingly, invasive podosomes [14–16] and guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor Dock180 (dedicator of cytokinesis 180) [17] appear to play a key role in both macrophage fusion and myoblast fusion. Note that finding that a specific protein activity is required for the formation of multinucleated cells does not necessarily implicate that protein in the cell fusion stage. It is important to verify that these proteins and structures are involved in fusion rather than in some pre-fusion processes and, if so, to identify the specific fusion stage.

Cell–cell fusion starts with opening of nanometre-sized fusion pores that connect the volumes of fusing cells. These pores can close [18] or give rise to long-living membrane nanotubes connecting cells [19]. In contrast, formation of multinucleated cells requires an expansion of the fusion pores. Early and late cell–cell fusion stages (formation of nascent membrane connections and their expansion) can be controlled by distinct protein machines and syncytium formation can be inhibited downstream of fusion pore opening [20,21]. Our earlier work has emphasized the importance of DNM2 (dynamin 2) in late stages of cell–cell fusion mediated by different viral fusogens [20] and in myoblast fusion [21]. If dynamin dependence of the late fusion stages is a conserved mechanistic motif, we expect late stages of macrophage fusion in osteoclast formation to be also controlled by dynamin activity. Dynamin is one of the key regulators of cell physiology [22] including osteoclast function [23–26], and any dynamin dependence of late fusion stages will have to be distinguished from dynamin dependences of pre-fusion and early fusion stages of osteoclast formation.

In our recent study [21], to explore myoblast fusion in development and regeneration of skeletal muscle, we uncoupled fusion stage from pre-fusion processes using LPC (lysophosphatidylcholine).LPC reversibly blocks hemifusion,i.e. the merger of the contacting leaflets of two membranes at the onset of their fusion [27]. Thus an LPC block allowed us to accumulate ready-to-fuse myoblasts and to observe the irrelatively synchronized fusion upon LPC removal. In the present study, we have applied the LPC block synchronization approach to osteoclast formation by the macrophage-like cells of the RAW 264.7 murine cell line (RAW cells) treated with RANKL and by human monocytes treated with M-CSF and RANKL. We concentrated cell–cell fusion events that normally develop within 16 h to develop within 30–90 min. To detect both completed cell fusion events and fusion events stalled downstream of a local merger between cell membranes, we complemented syncytium formation assay (the conventional way of quantifying osteoclast fusion) with an assay in which we detected early membrane connections as appearance of co-labelled cells after co-incubation of differently labelled fusion-committed macrophages. Using these novel experimental approaches, we found that dynamin controls expansion of early fusion intermediates required for the formation of multinucleated osteoclasts.

EXPERIMENTAL

Cells

RAW 264.7 mouse macrophage cell line (A.T.C.C., Manassas, VA, U.S.A.) (RAW cells, passage number ≤5) were maintained in a humidified incubator (5% CO2 in air) at 37°C in DMEM (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium) (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS (Valley Biomedical) and penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). Osteogenic differentiation of the cells was triggered by plating them at time zero on a 35-mm-diamater cell culture dish into the same medium supplemented with 50 ng/ml mouse RANKL (Cell Sciences) for 3–5 days. During the entire course of cell differentiation, we refreshed RANKL-supplemented medium every 3 days.

Elutriated human monocytes from healthy donors were provided by the Combined Technical Research Core, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), National Institutes of Health (NIH). Monocytes were seeded on to a 35-mm-diameter cell culture dish at 106 cells per dish density and cultured in MEM-Alpha (Life Technologies) containing 10% (v/v) FBS and penicillin/streptomycin. Osteoclast differentiation was induced by incubation of the cells in the medium supplemented with 25 ng/ml human M-CSF (Cell Sciences) for the first 6 days (the medium was refreshed on the third day) followed by incubation in the medium containing 25 ng/ml MCSF and 30 ng/ml human RANKL (Cell Sciences) that was refreshed every third day.

LPC block

A 10 mg/ml stock solution of lauroyl-LPC (1-lauroyl-2-hydroxysn-glycero-3- phosphocholine) (Avanti Polar Lipids) was freshly prepared in water [21]. To block osteoclast fusion, differentiating RAW cells at 72 h were supplemented with the fresh culture medium containing 50 ng/ml murine RANKL and 170 μM LPC. Differentiating human monocytes at 216 h (ninth day) after RANKL application were supplemented with the fresh culture medium containing 25 ng/ml human M-CSF, 30 ng/ml human RANKL and 350 μM LPC. After 16 h (88 h for RAW cells, 232 h for monocytes) LPC was removed by five washes with LPC-free culture medium.

Application of reagents

To explore the effects of intracellular ATP depletion on the synchronized fusion stage, we applied a mixture of 2.5 mM sodium azide and 5 mM 2-deoxy-D-glucose in DMEM to fusion-committed RAW cells, 30 min before LPC removal. Dynamin GTPase inhibitors Dynasore [28] and MiTMAB [29] (Sigma) were applied to fusion-committed RAW cells and human monocytes at the time of LPC removal.

Fusion assay

For evaluation of the efficiency of macrophage fusion, RAW cells and human monocytes were fixed with 10% (w/v) formalin solution (Electron Microscopy Sciences)1.5 h after LPC removal, and cell nuclei were labelled with Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes). Images were captured at room temperature in Dulbecco’s PBS (Life Technologies) on an Axiovert 135 microscope (Carl Zeiss) equipped with 10×/0.30 Plan-NEOFLUAR objective lens (Carl Zeiss) and Coolsnap fx CCD (charge-coupled device) camera (Photometrics) using μManager 1.4 [30]. For each condition, images of ten random fields of view were acquired. The efficiency of osteoclast formation was quantified by counting total number of nuclei in all syncytia (RAW cells with ≥3nuclei) within a field and by evaluating the distribution profile of syncytium sizes (= number of nuclei per syncytium). For osteoclasts generated from human monocytes, the number of nuclei and area of each multinucleated osteoclast (cells with ≥2 nuclei) were quantified using semi-automated ImageJ (NIH) macros developed in-house and available from L.V.C. on request.

Membrane merger was assayed as redistribution of membrane and content-probes between cells labelled with different probes. At 72 h, fusion-committed RAW cells were labelled with either membrane dye DiI (Life Technologies) or cell content marker CellTracker™ Green (Life Technologies). DiI-labelled cells were lifted by scraping and overlaid on the CellTracker™ Green-labelled cells. After 2 h, the co-plated cells were placed into the medium supplemented with RANKL and LPC. After 16 h, LPC block was removed and 1.5 h later cells were fixed and images were captured both as described above and on an Axioskop microscope (Carl Zeiss) equipped with 20×/0.3 LD A-Plan objective lens (Carl Zeiss) and ORCA C4742–98 CCD camera (Hamamatsu Photonics) using MetaMorph 6.1 software (Molecular Devices). Membrane merger was scored as a percentage of syncytia that are co-labelled with both dyes to the total number of syncytia.

TRAP staining

The expression of an osteoclast marker TRAP (tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase) was evaluated using a TRAP staining kit (Kamiya Biomedical Company), as suggested by the manufacturer. For each condition, we took images of ten random fields of view. The efficiency of macrophage differentiation was quantified by measuring the total intensity of the TRAP-positive signal using ImageJ. We selected TRAP-positive areas by automatically setting thresholds using an IJ-Isodata algorithm for each brightfield image. We then applied morphological dilation and fill holes operations to the resulting binary image. The resulting image mask was applied to the inverted brightfield image to measure total TRAP intensity per image field.

Timelapse imaging

Timelapse images of fusion-committed human monocytes were recorded every 2 min using an iXon 885 EMCCD camera (Andor Technology) and μManager software package [30] on an AxiObserver D1 inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss) equipped with a 10×/0.45 Ph1 Plan-Apochromat objective lens (Carl Zeiss) and 617-nm LED transmitted light source (Mightex Systems). Temperature was maintained at 37°C using a DH-35iL culture dish incubator (Warner Instruments) under constant stream of a 95% air/5% CO2 gas mixture. Image sequences were filtered using an unsharp mask filter to improve contrast, a median filter to remove noise and, then, converted into uncompressed. avi files using ImageJ version 1.47d (NIH).

siRNA transfection

Fusion-committed RAW cells and human monocytes plated in a 35-mm-diameter culture dish (BD Biosciences) were transfected on day 3 and day 8 after RANKL application with mouse and human DNM2 siRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-35237 and sc-35236 respectively) respectively, using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. The siRNAs used were designed by the manufacturer as pools of three target-specific 19–25 nt siRNA duplexes designed to knock down DNM2 expression of murine DNM2 (sense: CCACACGUGUUGAACUUGAtt; GCAUCAAUCGUAUCUUUCAtt; CUAGUGGACAUGACAAUGAtt) and human DNM2 (sense: CCACACGUGUUGAACUUGAtt; UGGUGAAGAUGGAGUUUGAtt; AGCGAAUCGUCACCACUUAtt). These duplexes were designed by Santa Cruz Biotechnology by algorithm to areas that are not conserved and are specific to the gene target. Control siRNA consisted of a scrambled sequence designed by the manufacturer not to lead to the specific degradation of any cellular message. Formation of multinucleated cells was scored 24 h later for RAW cells and 36 h later for monocytes. Note that mouse DNM2 siRNA duplexes used in the present study have been shown to be very specific and have no off-target effects even for other dynamin isoforms [31].

Immunoblotting

DNM2 siRNA-transfected RAW cells were lysed at room temperature 24 h after transfection with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 0.2% SDS in phosphate buffer in the presence of a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). The lysates were processed and analysed using 3–8% NuPAGE Tris/acetate gel (Invitrogen), as described in [21].

Statistics

Results are expressed as means ± S.D. for the number of experiments stated. Significance was determined by a two-tailed Student’s t test carried out using Sigmaplot version 11.0 (Systat Software). We compared normally distributed data using the unpaired Student’s t test, and when the data were not normally distributed or failed the equal variance test, we used the Mann– Whitney rank sum test instead.

RESULTS

Accumulating ready-to-fuse macrophages using LPC block

As expected, 72 h after application of RANKL to RAW cells (time zero) we observed the appearance of relatively small multinucleated cells. The number and size of the multinucleated cells (the number of nuclei per cell) increased with time as a result of additional fusion events. We have focused on a very robust cell–cell fusion observed between 72 and 88 h. Although at 88 h, many cells in each field of view remain mononucleated, some of the multinucleated cells have more than 100 nuclei (Figure 1).

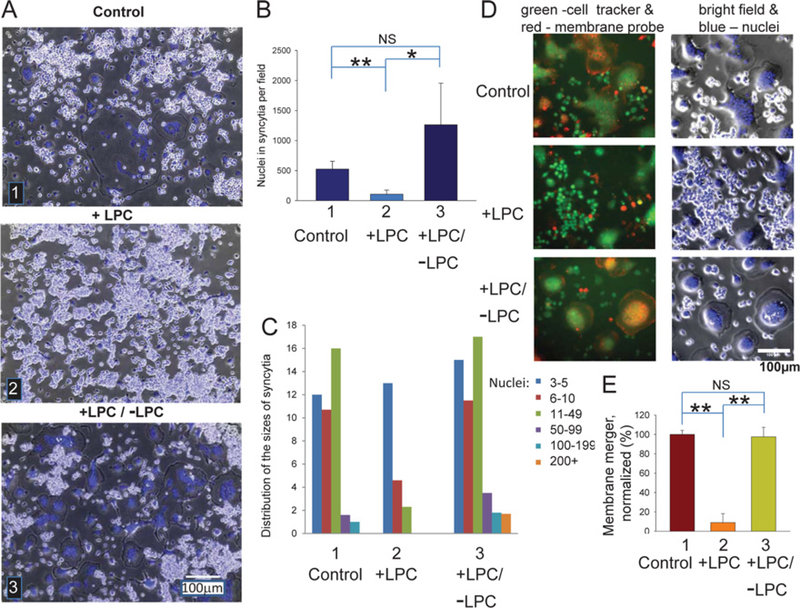

Figure 1. Synchronization of fusion between RAW cells using LPC block.

Osteogenic differentiation of RAW cells was triggered by RANKL application (time zero). (A) Brightfield with nuclear staining (blue) images of the RAW cells at 89.5 h. (1) Cells not treated with LPC (Control). (2) LPC applied at 72 h and not removed (+ LPC). (3) LPC applied at 72 h and removed at 88 h (+ LPC/ − LPC). (B) Cell fusion for each of the conditions described in (A) was quantified at 89.5 h as the total number of nuclei in syncytia per field. All results are means ± S.D. (n= 3). Levels of significance relative to control (bar 1) are shown as NS (not significant, P> 0.05); *P< 0.05 and **P< 0.001. (C) Distribution of the numbers of nuclei per syncytium in one representative experiment out of three experiments. (D and E) LPC reversibly blocks fusion between the cells labelled with CellTracker™ Green and red DiI detected as appearance of co-labelled cells. (1) Cells not treated with LPC (Control). (2) LPC was applied at 72 h and not removed (+ LPC). (3) LPC was applied at 72 h and removed at 88 h (+ LPC/ − LPC). Images were taken and membrane merger scored at 89.5 h. (D) Images (merged green and red fluorescence, left) and brightfield with nuclear staining (blue, right). (E) Number of co-labelled cells for each of the conditions described in (D) was normalized to that in control (bar 1). All results are means ± S.D. (n= 8). Levels of significance relative to control (bar 1) are shown as NS (not significant, P> 0.05) and **P< 0.001.

Application of the fusion inhibitor LPC at 72 h lowered the number of multinucleated cells and their sizes (the number of nuclei in a cell) observed at 88 h (Figures 1A–1C). Note that, even in the presence of LPC, we observed some small syncytia, suggesting that, at the time of LPC application, we already had some syncytia and LPC inhibited only subsequent fusion events. Fusion ensued upon LPC removal. Within 90 min, the level of fusion reached the level of fusion observed in the control experiments with no LPC applied. Fusion-inhibiting treatments may block either membrane merger, i.e. formation of the local connections between the membranes of the fusing cells at the onset of their fusion, or an expansion of these connections to fully unite the volumes of the cells into a syncytium [20,21]. To test whether LPC inhibits local membrane merger or only later fusion stages, we complemented syncytium formation assay with an assay in which we co-incubated the cells lablled with cytosolic CellTracker™ Green and cells labelled with the red membrane probe DiI. We found that LPC inhibited not only syncytium formation and growth but also the appearance of the syncytia labelled with both of the probes (Figures 1D and 1E). Thus, as expected, LPC inhibited fusion between RAW cells upstream of the cell membrane merger.

LPC has also reversibly blocked fusion between monocytes that were committed to osteoclast formation by M-CSF and RANKL application (Supplementary Figure S1). As with RAW cells, LPC removal resulted in a robust fusion process (Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Movie S1) with a much higher rate of fusion events than the rates observed in the cells that had not been exposed to LPC (Supplementary Movie S2). This robust fusion and the lack of major changes in the expression of osteoclast marker TRAP (Supplementary Figure S2) indicated that 16 h in the presence of a fusion-inhibiting concentration of LPC did not block osteogenic differentiation.

Synchronization of macrophage fusion by LPC block allowed us to separate the fusion stage from the upstream processes that prepare macrophages for fusion. Combining a syncytium formation assay and a lipid mixing assay allowed us to distinguish conditions that block only latest ages of syncytium formation from those that block fusion upstream of membrane merger at the early fusion stage.

Late stages of macrophage fusion depend on cell metabolism and dynamin

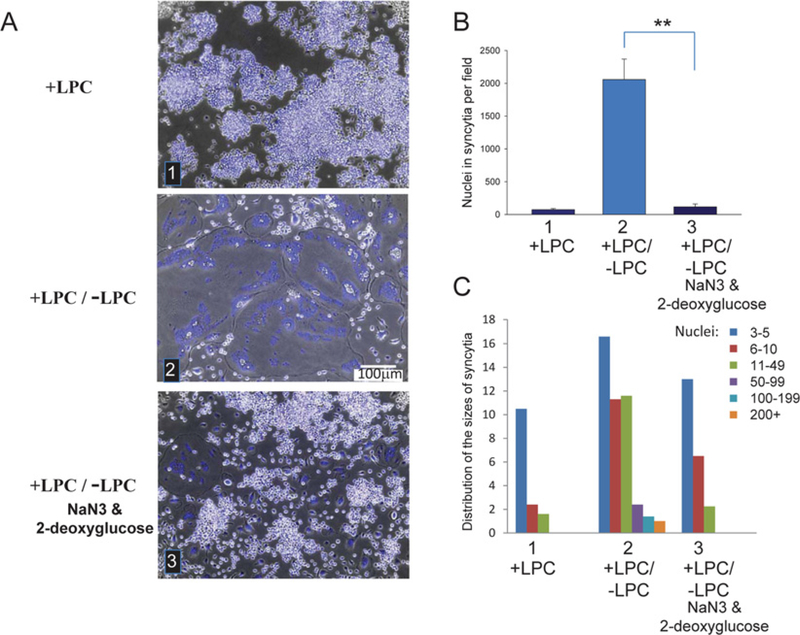

Synchronized fusion between RAW cells was inhibited by an ATP-depleting mixture of 2.5 mM sodium azide and 5 mM 2-deoxy-D-glucose applied 30 min before LPC removal (Figure 2).

Figure 2. ATP depletion inhibits synchronized fusion of RAW cells.

(A) Cells were committed to osteogenic differentiation by RANKL application at time zero and brightfield with nuclear staining (blue) images were taken at 89.5 h. (1) LPC applied at 72 h and not removed (+ LPC). (2) LPC was applied at 72 h and removed at 88 h (+ LPC/ − LPC). (3) As in (2), but, 30 min before LPC removal, the cells were treated with an ATP-depleting mixture of sodium azide and 2-deoxy-D-glucose. (B) Fusion between RAW cells for each of the conditions described in (A) was quantified at 89.5 h as the total number of nuclei in syncytia per field. All results are means ± S.D. (n≥6). **P< 0.001. (C) Distribution of the numbers of nuclei per syncytium in one representative experiment out of six experiments.

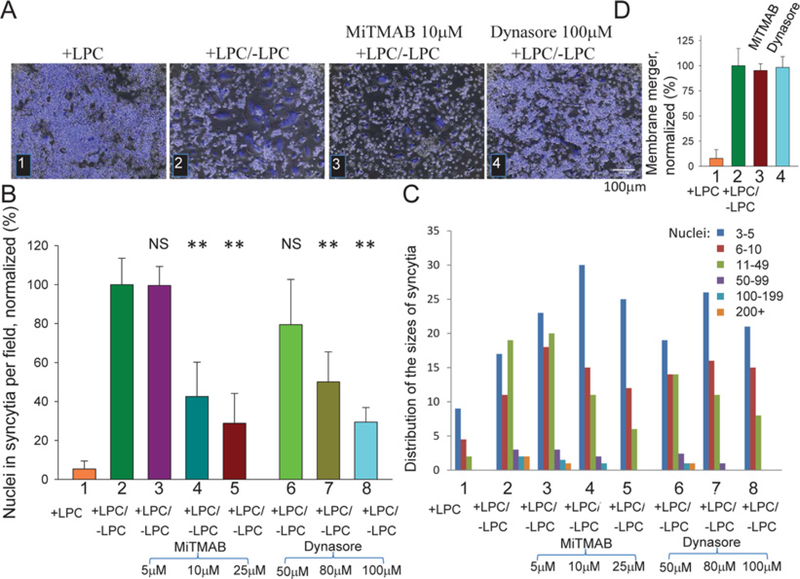

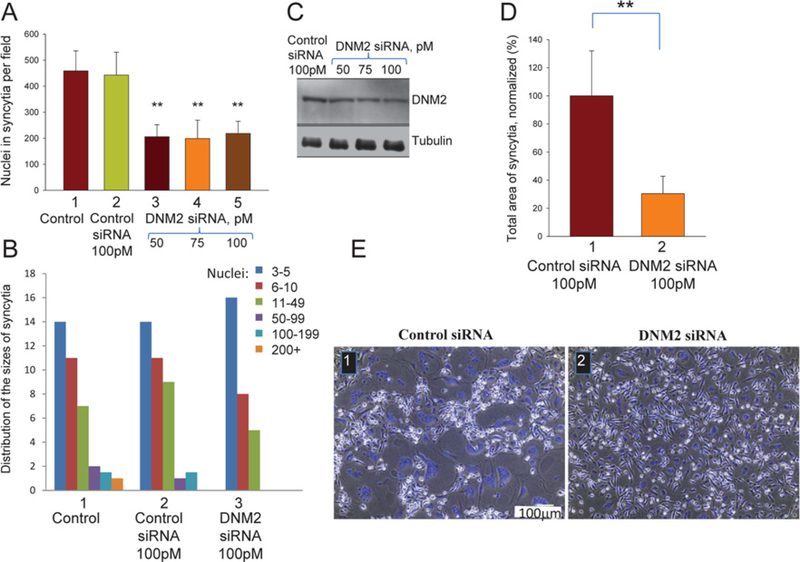

One of the proteins that could be affected by ATP depletion is dynamin [32], a protein implicated in cell–cell fusion initiated by viral fusogens [20] and in myoblast fusion [21]. To test whether synchronized fusion between RAW cells involves this protein, we used dynamin GTPase inhibitors Dynasore [28] and MitMAB [29] applied at the time of LPC removal. Both inhibitors suppressed syncytium formation (Figures 3A–3C), but did not suppress membrane merger (Figure 3D), suggesting that dynamin is involved in expansion of nascent membrane connections at the late stages of the cell fusion. Dynasore also inhibited fusion between monocyte-derived macrophages (Supplementary Figure S3). Small-molecule inhibitors of dynamin have off-target effects on cell physiology [33]. To confirm the importance of dynamin in osteoclastogenesis, we transfected murine RAW cells and human monocytes at the pre-osteoclast stage with siRNAs targeting murine and human DNM2 respectively, and found that suppression of DNM2 expression inhibits unsynchronized (no LPC applied) formation of multinucleated cells in both experimental systems (Figure 4). This inhibition cannot be explained by non-specific effects of the siRNA transfection, since non-targeting siRNAs (control siRNA) had no effect on syncytium formation. Note that, in contrast with fast-acting inhibitors interfering with dynamin activity during synchronized fusion (Figure 3),targeting dynamin with siRNA (and, potentially, with dynamin mutants) works much more slowly and can also influence pre-fusion stages of the process.

Figure 3. In contrast with membrane merger, synchronized formation of multinucleated osteoclasts depends on dynamin activity.

(A) RAW cells were committed to osteogenesis by RANKL application at time zero and bright field with nuclear staining (blue) images were taken at 89.5 h. (1) LPC applied at 72 h and not removed (+ LPC). (2) LPC applied at 72 h and removed at 88 h (+ LPC/ − LPC). (3 and 4) As in (2), but either 10 μM MiTMAB or 100 μM Dynasore was applied at the time of LPC removal. (B) Synchronized fusion of RAW cells treated or not treated with different concentrations of either MiTMAB and Dynasore was quantified at 89.5 h as the total number of nuclei in syncytia per field and normalized to fusion in the control experiment where LPC was removed and the cells were treated with neither of the dynamin inhibitors (bar 2). All results are means ± S.D. (n≥6). Levels of significance relative to control (bar 2) are shown as NS (not significant, P> 0.05) and **P< 0.001. (C) Distribution of the numbers of nuclei per syncytium for each of the conditions described in (B) in one representative experiment out of six experiments. (D) Neither 25 μM MiTMAB (3) nor 100 μM Dynasore (4) applied at the time of LPC removal inhibited synchronized fusion between RAW cells quantified using the membrane merger assay. In control experiments, we skipped application of the dynamin inhibitors and either removed or did not remove LPC (2 and 1 respectively). Data were normalized with respect to bar 2 (+ LPC/ − LPC). All results are means ± S.D. (n≥6).

Figure 4. siRNA suppression of DNM2 expression inhibits formation of multinucleated osteoclasts.

(A) RAW cells transfected with control siRNA or DNM2 siRNA (bars 2 and 3 respectively) at 72 h were committed to osteogenic differentiation by RANKL application. Bar 1 is control with untransfected cells. Fusion was quantified at 96 h as the total number of nuclei in syncytia per field. All results are means ± S.D. (n≥10). The level of significance relative to control siRNA (bar 2) is shown as **P< 0.001. (B) Distribution of the numbers of nuclei per syncytium for non-transfected cells and the cells transfected with either control or DNM2 siRNAs in one representative experiment out of ten experiments. (C) The RAW cells transfected with control or DNM2 siRNAs were lysed at 96 h and analysed by Western blotting to evaluate the levels of expression of DNM2 and tubulin (a loading control). (D) As in (A), but with human monocytes transfected with either control siRNA or DNM2 siRNA (bars 1 and 2 respectively) at 192 h (eighth day). Formation of multinucleated cells was quantified at 228 h (10.5 days after RANKL application) by measuring their areas and normalized to that for the cells transfected with control siRNA (bar 1). The results are means ± S.D. (n≥7). The level of significance relative to control (bar 1) is shown as **P< 0.001. (E) Brightfield with nuclear staining (blue) images of the monocytes transfected with the control siRNA (1) and DNM2 siRNA (2). Images were taken at 228 h.

DISCUSSION

Synchronization of cell–cell fusion using LPC block allowed us to uncouple the cell–cell fusion stage of osteoclast formation from many differentiation processes that prepare macrophages for fusion. We then divided synchronized cell–cell fusion into two distinct stages: (i) formation, and (ii) expansion of the membrane connections. The latter stage depends on dynamin activity as is evident from the inhibitory effects of Dynasore, MiTMAB and DNM2 siRNA on formation and growth of multinucleated osteoclasts. Intriguingly, a merger between the membranes of the two cells was not affected by even high concentrations of the dynamin inhibitors. Regardless of any possible off-target effects of Dynasore and MiTMAB, both of these drugs have been shown to rapidly and efficiently block GTPase activity of dynamin in cells [28,29].Thus we identify the expansion of membrane connections as a dynamin-dependent stage of osteoclast fusion. Dynamin-dependence of osteoclast formation is consistent with a recent identification of dynamin as a novel target for bisphosphonates, drugs widely used to prevent the osteoclast-mediated loss of bone mass [34].

The dependences on dynamin and cell metabolism have been reported for the late stages of other cell–cell fusion processes including myoblast fusion [21] and cell fusion initiated by viral fusogens [20]. The specific mechanisms underlying these conserved dependences remain to be clarified. Dynamin may regulate late fusion stages by controlling reorganization of actin cytoskeleton [35] associated with cell–cell fusion [26,36–40]. Studies on myoblast fusion [14,16,41] and osteoclast formation [4,15] emphasize the functional importance of invasive actin-rich podosome-like membrane protrusions.We suggest that membrane stresses generated by these podosomes drive expansion of nascent membrane connections. This hypothesis would explain why ATP depletion and dynamin inhibition, both known to suppress formation of membrane protrusions and podosomes [25,42],block late stages of syncytium formation. The importance of dynamin, a key regulator of endocytosis, in syncytium formation may also suggest that the cytoplasmic bridge between fusing cells expands by vesiculation of the cell contact zone ([43,44], but see [14,37]). Furthermore, in addition to the uncovered involvement of dynamin in the late fusion stages, this protein can be important in other pre- and post-fusion stages of osteoclastogenesis.

To summarize, the present work emphasizes the conserved mechanistic motifs shared by cell–cell fusion processes in osteoclast formation, muscle development and regeneration and, possibly, by other cell–cell fusions. In addition to the conserved dependence of late fusion stages on dynamin, finding that hemifusion-inhibitor LPC reversibly blocks fusion of macrophages upstream of membrane merger indicates that macrophage fusion, like many other well-characterized fusion processes, proceeds via the fusion-through-hemifusion pathway. Future identification and characterization of the proteins that mediate the membrane merger stage of osteoclast formation facilitated by our fusion synchronization approach will hopefully elucidate the similarities and distinctions between fusion proteins that initiate diverse cell–cell fusions.

While this paper was under review, an independent study was published that also reports the importance of dynamin in osteoclast fusion [45].

Supplementary Material

Time-lapse movie of largely synchronized fusion between human monocytes. Fusion-committed monocytes were incubated for 216h (9 days) in the culture medium containing M-CSF/RANKL and then maintained for 16h in the culture medium supplemented with M-CSF, RANKL and LPC. At t = 0, the cells were washed to remove LPC and to allow cell fusion. The cells were then transferred into a microscope stage culture dish incubator for imaging. Images were analyzed by timelapse phase-contrast microscopy using a custom setup as described in the Experimental. Frames were taken every 2 min for 3 h. The image field is 380 μm x 360 μm.

Time-lapse movie of unsynchronized fusion between monocytes. Control experiment that shows a few fusion events between-fusion committed human monocytes observed within the same time interval from 232h to 235h in the culture medium containing M-CSF/RANKL as in Video 1 for the cells that were not treated with LPC. Fusion committed human monocytes were incubated for 232h in the culture medium containing M-CSF/RANKL and then transferred into a microscope stage culture dish incubator for imaging. Images were analyzed as in movie 1. The image field is 380 μm x 360 μm.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr Michael T. Collins (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research) for helpful discussions. We also thank George McGrady (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research) for providing us with elutriated monocytes.

FUNDING

The research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health (to L.V.C.).

Abbreviations

- CCD

charge-coupled device

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- DNM2

dynamin 2

- LPC

lysophosphatidylcholine

- M-CSF

macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- RANKL

receptor activator for NF-κB (nuclear factor κB) ligand

- TRAP

tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen EH, Grote E, Mohler W and Vignery A (2007) Cell–cell fusion. FEBS Lett. 581, 2181–2193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sapir A, Avinoam O, Podbilewicz B and Chernomordik LV (2008) Viral and developmental cell fusion mechanisms: conservation and divergence. Dev. Cell 14, 11–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teitelbaum SL (2000) Bone resorption by osteoclasts. Science 289, 1504–1508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oikawa T, Kuroda Y and Matsuo K (2013) Regulation of osteoclasts by membrane-derived lipid mediators. Cell. Mol. Life Sci 70, 3341–3353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vignery A (2008) Macrophage fusion: molecular mechanisms. Methods Mol. Biol 475, 149–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyamoto T (2011) Regulators of osteoclast differentiation and cell–cell fusion. Keio J. Med 60, 101–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yagi M, Miyamoto T, Sawatani Y, Iwamoto K, Hosogane N, Fujita N, Morita K, Ninomiya K, Suzuki T, Miyamoto K et al. (2005) DC-STAMP is essential for cell–cell fusion in osteoclasts and foreign body giant cells. J. Exp. Med 202, 345–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyamoto H, Suzuki T, Miyauchi Y, Iwasaki R, Kobayashi T, Sato Y, Miyamoto K, Hoshi H, Hashimoto K, Yoshida S et al. (2012) Osteoclast stimulatory transmembrane protein and dendritic cell-specific transmembrane protein cooperatively modulate cell–cell fusion to form osteoclasts and foreign body giant cells. J. Bone Miner. Res 27, 1289–1297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pellegatti P, Falzoni S, Donvito G, Lemaire I and Di Virgilio F (2011) P2X7 receptor drives osteoclast fusion by increasing the extracellular adenosine concentration. FASEB J. 25, 1264–1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinberg TH and Hiken JF (2007) P2 receptors in macrophage fusion and osteoclast formation. Purinergic Signal. 3, 53–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soe K, Andersen TL, Hobolt-Pedersen AS, Bjerregaard B, Larsson LI and Delaisse JM (2011) Involvement of human endogenous retroviral syncytin-1 in human osteoclast fusion. Bone 48, 837–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhee I, Davidson D, Souza CM, Vacher J and Veillette A (2013) Macrophage fusion is controlled by the cytoplasmic protein tyrosine phosphatase PTP-PEST/PTPN12. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 2458–2469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang H, Kerloc’h A, Rotival M, Xu X, Zhang Q, D’Souza Z, Kim M, Scholz JC, Ko J-H, Srivastava PK et al. (2014) Kcnn4 is a regulator of macrophage multinucleation in bone homeostasis and inflammatory disease. Cell Rep. 8, 1210–1224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sens KL, Zhang S, Jin P, Duan R, Zhang G, Luo F, Parachini L and Chen EH (2010) An invasive podosome-like structure promotes fusion pore formation during myoblast fusion. J. Cell Biol 191, 1013–1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oikawa T, Oyama M, Kozuka-Hata H, Uehara S, Udagawa N, Saya H and Matsuo K (2012) Tks5-dependent formation of circumferential podosomes/invadopodia mediates cell–cell fusion. J. Cell Biol 197, 553–568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shilagardi K, Li S, Luo F, Marikar F, Duan R, Jin P, Kim JH, Murnen K and Chen EH (2013) Actin-propelled invasive membrane protrusions promote fusogenic protein engagement during cell–cell fusion. Science 340, 359–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pajcini KV, Pomerantz JH, Alkan O, Doyonnas R and Blau HM (2008) Myoblasts and macrophages share molecular components that contribute to cell–cell fusion. J. Cell Biol 180, 1005–1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Razinkov VI, Melikyan GB and Cohen FS (1999) Hemifusion between cells expressing hemagglutinin of influenza virus and planar membranes can precede the formation of fusion pores that subsequently fully enlarge. Biophys. J 77, 3144–3151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis DM and Sowinski S (2008) Membrane nanotubes: dynamic long-distance connections between animal cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 9, 431–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richard JP, Leikina E, Langen R, Henne WM, Popova M, Balla T, McMahon HT, Kozlov MM and Chernomordik LV (2011) Intracellular curvature-generating proteins in cell-to-cell fusion. Biochem. J 440, 185–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leikina E, Melikov K, Sanyal S, Verma SK, Eun B, Gebert C, Pfeifer K, Lizunov VA, Kozlov MM and Chernomordik LV (2013) Extracellular annexins and dynamin are important for sequential steps in myoblast fusion. J. Cell Biol 200, 109–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferguson SM and De Camilli P (2012) Dynamin, a membrane-remodelling GTPase. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 13, 75–88 PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruzzaniti A, Neff L, Sandoval A, Du L, Horne WC and Baron R (2009) Dynamin reduces Pyk2 Y402 phosphorylation and SRC binding in osteoclasts. Mol. Cell. Biol 29, 3644–3656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eleniste PP, Du L, Shivanna M and Bruzzaniti A (2012) Dynamin and PTP-PEST cooperatively regulate Pyk2 dephosphorylation in osteoclasts. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol 44, 790–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Destaing O, Ferguson SM, Grichine A, Oddou C, De Camilli P, Albiges-Rizo C and Baron R (2013) Essential function of dynamin in the invasive properties and actin architecture of v-Src induced podosomes/invadosomes. PLoS ONE 8, e77956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takito J, Otsuka H, Yanagisawa N, Arai H, Shiga M, Inoue M, Nonaka N and Nakamura M (2014) Regulation of osteoclast multinucleation by the actin cytoskeleton signaling network. J. Cell. Physiol, doi: 10.1002/jcp.24723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chernomordik LV and Kozlov MM (2005) Membrane hemifusion: crossing a chasm in two leaps. Cell 123, 375–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macia E, Ehrlich M, Massol R, Boucrot E, Brunner C and Kirchhausen T (2006) Dynasore, a cell-permeable inhibitor of dynamin. Dev. Cell 10, 839–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quan A, McGeachie AB, Keating DJ, van Dam EM, Rusak J, Chau N, Malladi CS, Chen C, McCluskey A, Cousin MA and Robinson PJ (2007) Myristyl ammonium bromide are surface-active small molecule dynamin inhibitors that block endocytosis mediated by dynamin I or dynamin II. Mol. Pharmacol 72, 1425–1439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edelstein A, Amodaj N, Hoover K, Vale R and Stuurman N (2010) Computer control of microscopes using μManager. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol Chapter 14,, Unit14.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanifuji S, Funakoshi-Tago M, Ueda F, Kasahara T and Mochida S (2013) Dynamin isoforms decode action potential firing for synaptic vesicle recycling. J. Biol. Chem 288, 19050–19059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwoebel ED, Ho TH and Moore MS (2002) The mechanism of inhibition of Ran-dependent nuclear transport by cellular ATP depletion. J. Cell Biol 157, 963–974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park RJ, Shen H, Liu L, Liu X, Ferguson SM and De Camilli P (2013) Dynamin triple knockout cells reveal off target effects of commonly used dynamin inhibitors. J. Cell Sci 126, 5305–5312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Masaike Y, Takagi T, Hirota M, Yamada J, Ishihara S, Yung TM, Inoue T, Sawa C, Sagara H, Sakamoto S et al. (2010) Identification of dynamin-2-mediated endocytosis as a new target of osteoporosis drugs, bisphosphonates. Mol. Pharmacol 77, 262–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schafer DA (2004) Regulating actin dynamics at membranes: a focus on dynamin. Traffic 5, 463–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Massarwa R, Carmon S, Shilo BZ and Schejter ED (2007) WIP/WASp-based actin-polymerization machinery is essential for myoblast fusion in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 12, 557–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen A, Leikina E, Melikov K, Podbilewicz B, Kozlov MM and Chernomordik LV (2008) Fusion-pore expansion during syncytium formation is restricted by an actin network. J. Cell Sci 121, 3619–3628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gildor B, Massarwa R, Shilo BZ and Schejter ED (2009) The SCAR and WASp nucleation-promoting factors act sequentially to mediate Drosophila myoblast fusion. EMBO Rep. 10, 1043–1050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ishikawa A, Omata W, Ackerman, 4th, W. E., Takeshita, T., Vandré, D. D. and Robinson, J. M. (2014) Cell fusion mediates dramatic alterations in the actin cytoskeleton, focal adhesions, and E-cadherin in trophoblastic cells. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 71, 241–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bothe I, Deng S and Baylies M (2014) PI(4,5)P2 regulates myoblast fusion through Arp2/3 regulator localization at the fusion site. Development 141, 2289–2301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Onel SF and Renkawitz-Pohl R (2009) FuRMAS: triggering myoblast fusion in Drosophila. Dev. Dyn 238, 1513–1525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bear JE, Svitkina TM, Krause M, Schafer DA, Loureiro JJ, Strasser GA, Maly IV, Chaga OY, Cooper JA, Borisy GG and Gertler FB (2002) Antagonism between Ena/VASP proteins and actin filament capping regulates fibroblast motility. Cell 109, 509–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doberstein SK, Fetter RD, Mehta AY and Goodman CS (1997) Genetic analysis of myoblast fusion: blown fuse is required for progression beyond the prefusion complex. J. Cell Biol. 136, 1249–1261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mohler WA, Simske JS, Williams-Masson EM, Hardin JD and White JG (1998) Dynamics and ultrastructure of developmental cell fusions in the Caenorhabditis elegans hypodermis. Curr. Biol 8, 1087–1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shin NY, Choi H, Neff L, Wu Y, Saito H, Ferguson SM, De Camilli P and Baron R (2014) Dynamin and endocytosis are required for the fusion of osteoclasts and myoblasts. J. Cell Biol 207, 73–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Time-lapse movie of largely synchronized fusion between human monocytes. Fusion-committed monocytes were incubated for 216h (9 days) in the culture medium containing M-CSF/RANKL and then maintained for 16h in the culture medium supplemented with M-CSF, RANKL and LPC. At t = 0, the cells were washed to remove LPC and to allow cell fusion. The cells were then transferred into a microscope stage culture dish incubator for imaging. Images were analyzed by timelapse phase-contrast microscopy using a custom setup as described in the Experimental. Frames were taken every 2 min for 3 h. The image field is 380 μm x 360 μm.

Time-lapse movie of unsynchronized fusion between monocytes. Control experiment that shows a few fusion events between-fusion committed human monocytes observed within the same time interval from 232h to 235h in the culture medium containing M-CSF/RANKL as in Video 1 for the cells that were not treated with LPC. Fusion committed human monocytes were incubated for 232h in the culture medium containing M-CSF/RANKL and then transferred into a microscope stage culture dish incubator for imaging. Images were analyzed as in movie 1. The image field is 380 μm x 360 μm.