Abstract

Background

Multiple features in the presentation of randomized controlled trial (RCT) results are known to influence comprehension and interpretation. We aimed to compare interpretation of cancer RCTs with time-to-event outcomes when the reported treatment effect measure is the hazard ratio (HR), difference in restricted mean survival times (RMSTD), or both (HR+RMSTD). We also assessed the prevalence of misinterpretation of the HR.

Methods

We carried out a randomized experiment. We selected 15 cancer RCTs with statistically significant treatment effects for the primary outcome. We masked each abstract and created three versions reporting either the HR, RMSTD, or HR+RMSTD. We randomized corresponding authors of RCTs and medical residents and fellows to one of 15 abstracts and one of 3 versions. We asked how beneficial the experimental treatment was (0–10 Likert scale). All participants answered a multiple-choice question about interpretation of the HR. Participants were unaware of the study purpose.

Results

We randomly allocated 160 participants to evaluate an abstract reporting the HR, 154 to the RMSTD, and 155 to both HR+RMSTD. The mean Likert score was statistically significantly lower in the RMSTD group when compared with the HR group (mean difference −0.8, 95% confidence interval, −1.3 to −0.4, P < 0.01) and when compared with the HR+RMSTD group (difference −0.6, −1.1 to −0.1, P = 0.05). In all, 47.2% (42.7%−51.8%) of participants misinterpreted the HR, with 40% equating it with a reduction in absolute risk.

Conclusion

Misinterpretation of the HR is common. Participants judged experimental treatments to be less beneficial when presented with RMSTD when compared with HR. We recommend that authors present RMST-based measures alongside the HR in reports of RCT results.

Keywords: survival analysis, randomized controlled trial, cancer, hazard ratio, restricted mean survival times

Key Message

In this randomized experiment of 469 authors of randomized trials and medical residents and fellows, we found that misinterpretation of hazard ratios (HRs) was common, with 40% equating it with an absolute risk reduction. Participants judged experimental treatments to be less beneficial when the measure of effect was the difference in restricted mean survival times when compared with the HR.

Introduction

Time-to-event outcomes are paramount in cancer randomized controlled trials (RCTs). In this context, the hazard ratio (HR) is increasingly used to measure treatment effects [1]. The HR does not provide any information on the cumulative risks of the outcome, but it may be misinterpreted as a relative risk (Figure 1) [2].

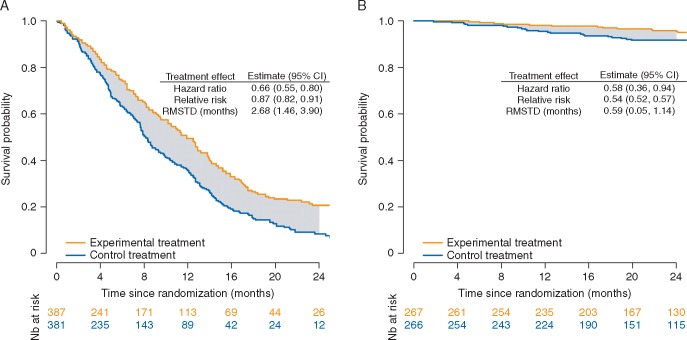

Figure 1.

Illustrative examples for the interpretation of hazard ratio, relative risk, and difference in restricted mean survival times. (A) The cumulative risk of death at 24 months is 95%. Because the outcome is frequent, it follows that the HR of 0.66 (95% CI 0.55–0.80) differs from the RR of 0.87 (0.82–0.91). Misinterpreting this HR as an RR leads to overestimating the reduction in risk of mortality. The correct interpretation of the HR is that, on a given day, an individual still at risk on the experimental treatment is 0.66 times as likely to experience death compared with an individual on the control treatment. In contrast, the RR indicates a 13% reduction in mortality risk at 24 months with the experimental treatment when compared with the control treatment (or equivalently a relative risk reduction of 13%). Finally, the RMSTD indicates a 2.68-month gain in life expectancy over 24 months for those on the experimental treatment when compared with control. (B) The cumulative risk of event at 24 months is 14%. Because the outcome is relatively infrequent, it follows that the HR of 0.58 (0.36–0.94) approximates the RR of 0.54 (0.52–0.57). The RMSTD is small, indicating that those on the experimental treatment live only 0.59 months longer, on average, compared with those on the control treatment. In any case, at any time point t, the hazard (or rate) of death pertains only to participants still at risk of death; the hazard ratio compares the experimental and control groups with respect to the instantaneous risks of death at time t only within participants surviving up to t; in contrast, the relative risk compares the cumulative risks of dying up to time t; the difference in restricted mean survival times quantifies the gain (or loss) in event-free survival over the time interval from 0 to t.

An additional method for measuring treatment effects with censored data is the difference in restricted mean survival times (RMSTD). The RMSTD compares the mean survival times between the experimental and control groups up to a fixed time point [3–5]. The RMSTD addresses the fundamental, and clinically important, question of how much longer, on average, those in the experimental group live, over a fixed time horizon. The RMSTD gives an intuitive absolute measure of the treatment effect in the time domain [6]. It is likely to be meaningful to clinicians and patients because absolute effects, not relative effects, are what generally matter for clinical decision-making [7, 8].

It is known that the presentation of results can influence impression of treatment benefit [9, 10]. We have previously shown that RMST-based treatment effect measures yield more conservative estimates than HRs [5]. To our knowledge, there is no prior evidence examining how clinicians interpret the HR and how they assess the clinical significance of treatments according to the HR or the RMSTD. We conducted a vignette-based randomized experiment to assess (i) how reporting the HR or RMSTD in RCT abstracts influences the interpretation of the results and (ii) the prevalence of misinterpretation of the HR.

Methods

We surveyed corresponding authors of RCTs, medical residents, and fellows. We randomly allocated participants to review an abstract for 1 of the 15 cancer RCTs with primary time-to-event outcomes. We further randomized participants to one of the three versions of the abstract according to the treatment effect measure for the primary outcome: HR, RMSTD, or both (HR+RMSTD).

The Institutional Review Board at Boston Medical Center (BMC) approved the protocol and we registered it with the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/uqwxc/).

Selection of trials

We selected 15 RCTs among 54 from our previous systematic review (supplementary data S1, available at Annals of Oncology online) [5]. To determine the 15 RCTs for inclusion, we selected superiority RCTs in solid tissue cancers with a single primary time-to-event outcome. We further selected RCTs that reported the HR for the primary outcome in the abstract, the corresponding Kaplan–Meier curves, and showed a statistically significant effect estimate. Across these 15 RCTs, the primary end point was PFS in 10 RCTs and OS in 5 RCTs; the HR ranged from 0.21 to 0.86; the RMSTD ranged from 1.14 to 6.57 months.

Construction of vignettes

We used a pre-specified methodology to edit and standardize the selected abstracts (supplementary data S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). We masked treatment names to reduce the ability to recognize RCTs. Three authors constructed the vignettes with a formal review and consensus process (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

From the standardized abstract, we further created three versions according to the treatment effect measure for the primary outcome. We first reconstructed individual patient data from the Kaplan–Meier curves of each RCT [11]. We pre-specified the time horizon in each RCT as the minimum of the largest event times in each group. We calculated the (unadjusted) HR and the RMSTD. We replaced the original HR in the abstract by the reconstructed HR for the HR group, by the RMSTD for the RMSTD group, and by the reconstructed HR followed by the RMSTD for the HR+RMSTD group.

Participants and recruitment strategy

We invited corresponding authors of cancer RCTs published or completed between 2010 and 2018 to participate. We also invited corresponding authors of non-cancer RCTs, as they would be presumably less influenced by the subject matter. We identified the email addresses by searching PUBMED and clinicaltrials.gov (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). Finally, we invited all residents and fellows at BMC as of February 2018 to participate. As an incentive, we pledged to donate to the BMC Kids Fund if we reached 450 responses and we have done so. We sent email invitations between 20 February and 15 May 2018. Participants received at least one reminder email. We closed the survey on 23 May.

Online survey

We obtained participant consent and collected data using REDCap (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online) [12]. Subjects were unaware of the nature and purpose of the research. After consent, we provided participants with their randomly assigned abstract, asked them two questions to elicit their interpretation, and for their gender, age range, and previous training in epidemiology, biostatistics, or methods of RCTs—never completed a formal course, completed non-degree course(s), have masters or doctorate.

Random assignment

We randomly allocated participants to 1 of the 15 RCTs and to 1 of the 3 abstract versions using a centralized randomization scheme. A statistician generated the randomization list, stratified according to the 3 target populations with blocks of size 45, before study activation.

Outcomes

We pre-specified two outcomes: (i) degree to which participants judge the experimental treatment to be beneficial on an 11‐point Likert scale ranging from 0, not beneficial at all, to 10, extremely beneficial; (ii) misinterpretation of the HR. For the first outcome, we asked: ‘Based on the primary end point in the provided abstract, on a scale from 0 to 10, is the experimental treatment beneficial?’ For the second outcome, we used a multiple-choice question: ‘An RCT found an HR for death to be 0.70 at 24 months. Based on this information, which of the following statements is true? There is a: (a) 30% reduction in the absolute risk of death at 24 months on average; (b) 70% reduction in the absolute risk of death at 24 months on average; (c) 30% increase in survival time on average; (d) 70% increase in survival time on average; (e) we are unable to determine reduction in absolute risk or increase in survival time based on the provided information’. We considered responses (a) through (d) as misinterpretations of the HR.

Sample size

We computed the sample size necessary to detect a mean difference between any two abstract versions of 1.0-point on the 11-point Likert scale. We assumed a within-group standard deviation of 2.7 points [13, 14]. We used a Bonferroni correction for three pairwise comparisons resulting in an adjusted α of 0.0167. The required sample size was 150 per group to guarantee 80% power. Assuming that 50% of the population misinterpret the HR, 450 participants also would enable estimating this expected proportion with 4.62% absolute precision and 95% confidence interval (CI).

Statistical analysis

The study population consisted of participants who responded to the Likert scale score question. We estimated the mean differences in Likert scale score between groups, and the associated 95% CIs, with a two-level linear model, accounting for multiplicity. We used a random intercept to account for differences in how beneficial the experimental treatment was across the 15 RCTs. We estimated the proportion of participants misinterpreting the HR with 95% Wilson score CI. We conducted two pre-specified subgroup analyses, according to target population and previous training in epidemiology/biostatistics. We used two-tailed P values with a Bonferroni adjustment when relevant and a significance level of 0.05. We conducted all analyses with R version 3.4.4 (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

Results

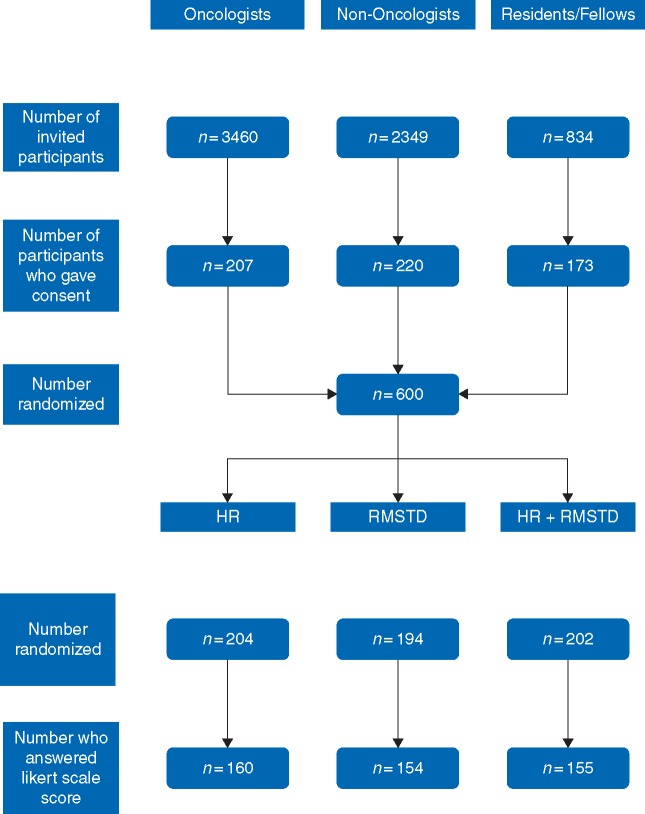

We randomized 160 participants to the HR group, 154 to the RMSTD group, and 155 to the HR+RMSTD group (Figure 2). In total, we sent 6643 email invitations and 600 (9%) individuals gave consent. Among those, 469 (78%) responded to the Likert scale score question and were included in the study. In all, 25% of participants were medical residents and fellows, 30% were women, and 42% were 50 years or older (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram showing the selection and randomization processes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants

| All | HRa | RMSTDa | HR+RMSTDa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 469 | N = 160 | N = 154 | N = 155 | |

| Target population | ||||

| Corresponding authors, cancer RCTs | 168 (35.8) | 57 (35.6) | 56 (36.4) | 55 (35.5) |

| Corresponding authors, non-cancer RCTs | 185 (39.5) | 66 (41.2) | 59 (38.3) | 60 (38.7) |

| Medical residents and fellows | 116 (24.7) | 37 (23.1) | 39 (25.3) | 40 (25.8) |

| Ageb | ||||

| 20–29 years | 55 (12.3) | 21 (13.8) | 17 (11.6) | 17 (11.3) |

| 30–39 years | 108 (24.1) | 31 (20.4) | 29 (19.9) | 48 (32.0) |

| 40–49 years | 99 (22.1) | 30 (19.7) | 31 (21.2) | 38 (25.3) |

| 50–59 years | 98 (21.9) | 38 (25.0) | 37 (25.3) | 23 (15.3) |

| 60–69 years | 77 (17.2) | 29 (19.1) | 26 (17.8) | 22 (14.7) |

| 70+ years | 11 (2.4) | 3 (2.0) | 6 (4.1) | 2 (1.3) |

| Genderb | ||||

| Female | 137 (30.4) | 40 (26.1) | 52 (35.4) | 45 (29.8) |

| Male | 312 (69.2) | 112 (73.2) | 94 (63.9) | 106 (70.2) |

| Not listed | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Prior training in epidemiology/biostatisticsb | ||||

| None | 158 (35.0) | 49 (32.0) | 56 (38.1) | 53 (35.1) |

| Non-degree course | 127 (28.2) | 50 (32.7) | 38 (25.9) | 39 (25.8) |

| Master or PhD | 166 (36.8) | 54 (35.3) | 53 (36.1) | 59 (39.1) |

Data are presented as No. (%).

Randomization groups: one of the three versions of the abstract according to the treatment effect measure for the primary outcome: hazard ratio (HR), difference in restricted mean survival times (RMSTD), or both (HR+RMSTD).

Missing data n = 21, n = 18, and n = 18 for age, gender, and prior training, respectively.

Interpretation of treatment effect

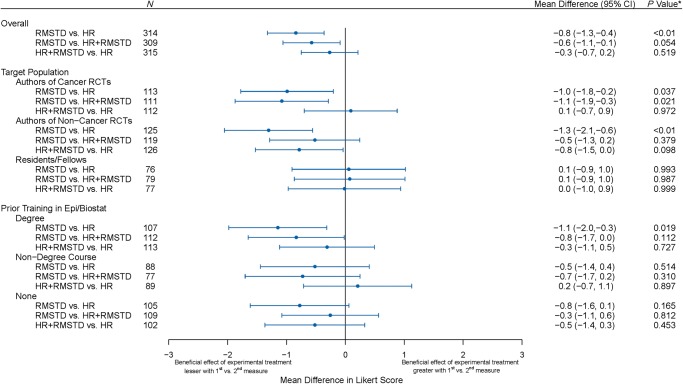

The mean Likert score evaluating the benefit of the treatment was 5.7 (95% CI from 5.2 to 6.2) in the HR group, 4.8 (4.4–5.3) in the RMSTD group and 5.4 (4.9–5.9) in the HR+RMSTD (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). The mean score was statistically significantly lower in the RMSTD group when compared with the HR group (mean difference −0.8, −1.3 to −0.4, P < 0.01) and when compared with the HR+RMSTD group (difference −0.6, −1.1 to −0.1, P = 0.05; Figure 3). There was no evidence of difference between the HR+RMSTD and the HR groups (difference −0.3, −0.7 to 0.2, P = 0.52).

Figure 3.

Forest plot showing the mean differences in Likert score between the three abstract versions. The plot shows the mean difference in Likert scores between each pair of randomization groups (first measure minus second measure). For example, the mean difference of −0.8 point indicates that the beneficial effect of the experimental treatment was perceived as lower when reading the RMSTD when compared with reading the HR. *Bonferroni adjusted P values.

In subgroup analyses, there was no evidence of interaction by target population (P = 0.11) or prior education (P = 0.68). The results were consistent among corresponding authors of cancer and non-cancer RCTs. However, among residents/fellows, the mean differences were close to the zero for all three comparisons. Regarding prior training, mean differences were larger among those with a degree in epidemiology/biostatistics (RMSTD versus HR −1.1, −2.0 to −0.3, P = 0.02, and RMSTD versus HR+RMSTD −0.8, −1.7 to 0.0, P = 0.11).

Lastly, the mean Likert scores were similar across the 15 vignettes (supplementary Figure S3, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Interpretation of HR

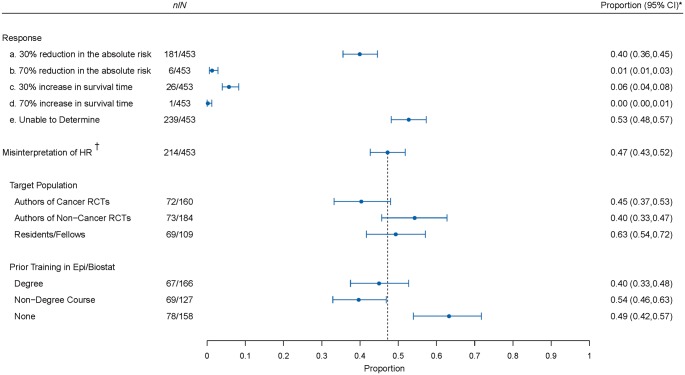

In all, 47.2% (95% CI, from 42.7% to 51.8%) of participants misinterpreted the HR either as providing information on the absolute risk or on survival time (Figure 4). The most common misinterpretation was interpreting the HR as the reduction in the absolute risk (i.e. as the relative risk), occurring in 40.0% (35.5%−44.5%) of participants. Interpreting the HR as the relative risk reduction was infrequent, occurring in 1.3% (0.6%−2.9%).

Figure 4.

Forest plot showing the prevalence of misinterpretation of the hazard ratio. The plot shows the proportion of participants selecting each of the multiple choice options for the interpretation of the HR. The dark circle indicates the point estimate with whiskers representing the corresponding 95% CI. Next, we show the prevalence of misinterpretation of the HR, i.e. participants who selected response a, b, c, or d. We also show the misinterpretation of HR by target population subgroup and by prior training subgroup. The dotted line indicates the overall proportion of HR misinterpretation. *95% CIs are adjusted for multiplicity. †Misinterpretation of HR is defined as selecting either response a, b, c, or d.

In subgroup analyses, there was a significant difference in the proportion of participants who misinterpreted the HR between the three target populations (P = 0.05) and according to prior training (P < 0.01). Among corresponding authors of cancer and non-cancer RCTs, 45.0% and 39.7% misinterpreted the HR, respectively, while 63.3% of residents/fellows misinterpreted it. The proportion who misinterpreted the HR was 40% among those with a degree in epidemiology/biostatistics, 49% among those who reported no previous training in epidemiology/biostatistics, and 54% among those who had completed a non-degree course.

Discussion

In this study, almost half of participants misinterpreted the HR, with ∼40% equating the HR with the relative risk. In addition, participants judged the experimental treatment to be less beneficial if the RCT abstract included only the RMSTD when compared with abstracts including the HR or both the HR and RMSTD.

While some members of the medical research community may be aware of misconceptions surrounding the HR, to our knowledge, this study is the first to generate empirical evidence regarding the widespread misinterpretation of HR as relative risks [2]. The direction of the HR is always the same as that of the relative risk, but the HR indicates nothing about the magnitude of the absolute risk reduction or about the timing of events [15]. The HR is frequently further from the null effect than the relative risk. Thus, equating the HR to the relative risk may lead to an optimistic interpretation of the benefit. A potential explanation for the common misinterpretation of the HR may be that many textbooks introduce the HR as being broadly similar to the relative risk in meaning and interpretation. In our study, misinterpretation of the HR was more common among participants who had completed a non-degree course in epidemiology/biostatistics. In addition, residents and fellows were more likely to misinterpret the HR. Including more effective epidemiology/biostatistics training in medical curricula should play an essential role in conveying the correct interpretation of HR as a rate ratio [16].

Participants applied different standards regarding the practical clinical significance of treatments when interpreting the HR and the RMSTD. The magnitude of the difference in Likert score was similar to that observed in a previous randomized experiment assessing the impact of spin [13]. Our finding may be explained by the fact that participants in the RMSTD group judged the gain in lifetime or time without progression to be minimal compared with participants in the HR group who misjudged the gain in terms of absolute risks. Another explanation could be that the HR lends itself to judgment of treatment benefit without having to conceptualize clinical significance. This finding has major implications regarding how clinicians perceive what constitutes a meaningful benefit to patients and whether they endorse the experimental treatment [17]. Finally, there was no significant difference between the group reading the HR alone when compared with both the HR and RMSTD. Participants in the HR+RMSTD group may have focused on the familiar HR, especially because we systematically presented the HR before the RMSTD.

Previous literature examining methods for communicating treatment effects has mostly focused on binary and continuous outcomes. In a systematic review of studies that evaluated risk communication formats, only 4 out of the 91 studies concerned time-to-event outcomes and none addressed the interpretation of the HR [18]. In a previous randomized experiment, Chao et al. found that presenting the relative risk reduction resulted in the highest rate of endorsement of the experimental treatment and recommended using the absolute survival benefit instead [10]. The impact of reporting the RMSTD in abstracts of RCTs had never been evaluated. Despite its methodological strengths—e.g. the use of a randomized design and of multiple vignettes based on real RCTs—our study needs to be replicated. In particular, absolute benefits for survival time in cancer tend to be small [5, 19].

Our study has limitations. First, we asked participants to evaluate the benefit of treatment based only on the abstract and the primary end point. However, clinicians typically rely on abstracts alone to guide their clinical decision-making [20]. In addition, preconceived notions of toxicity and burden of treatment also may have resulted in lower perceived benefit of experimental treatment. Second, our study relied on a limited sample of vignettes. However, results were consistent in the subgroup of corresponding authors of non-cancer RCTs, very likely completely unfamiliar with the RCTs, suggesting that our findings are not driven by the specific examples. Third, we focused on the RMSTD. Other options include the ratio of RMSTs or the RMST in each group [21]. Fourth, participants were corresponding authors of RCTs indexed on PUBMED or clinicaltrials.gov. Moreover, the overall response rate was 7%. Thus, participants may not be representative of end-users of RCTs. The proportion of female participants in our study was only 30%, consistent with gender differences in authorship [22]. We were able to reach our target sample size despite the low response rate. In keeping with literature on methods of increasing enrollment rates, we did not mention ‘survey’ in the email subject line, we used a donation incentive and in the reminder emails, we included the number who had already responded [23, 24].

In conclusion, we found that HR is commonly misinterpreted, most frequently as a relative risk. Moreover, participants judged experimental treatments as less beneficial when reading the RMSTD when compared with the HR. We recommend that authors present RMST-based measures alongside the HR in reports of RCT results.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants for volunteering their time to contribute to this study. We thank Tasha Coughlin (Boston University) for her help with REDCap for data collection and management.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences Interdisciplinary Training Grant for Biostatisticians (T32 GM 74905) and Boston University Clinical and Translational Science Institute (1UL1TR001430).

Disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Blagoev KB, Wilkerson J, Fojo T.. Hazard ratios in cancer clinical trials—a primer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2012; 9(3): 178–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sutradhar R, Austin PC.. Relative rates not relative risks: addressing a widespread misinterpretation of hazard ratios. Ann Epidemiol 2018; 28(1): 54–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Uno H, Claggett B, Tian L. et al. Moving beyond the hazard ratio in quantifying the between-group difference in survival analysis. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32(22): 2380–2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Royston P, Parmar MK.. Restricted mean survival time: an alternative to the hazard ratio for the design and analysis of randomized trials with a time-to-event outcome. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013; 13: 152.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Trinquart L, Jacot J, Conner SC, Porcher R.. Comparison of treatment effects measured by the hazard ratio and by the ratio of restricted mean survival times in oncology randomized controlled trials. JCO 2016; 34(15): 1813–1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pak K, Uno H, Kim DH. et al. Interpretability of cancer clinical trial results using restricted mean survival time as an alternative to the hazard ratio. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3(12): 1692–1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Poole C. On the origin of risk relativism. Epidemiology 2010; 21(1): 3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sedgwick P, Joekes K.. Interpreting hazard ratios. BMJ 2015; 351: h4631.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Naylor CD, Chen E, Strauss B.. Measured enthusiasm: does the method of reporting trial results alter perceptions of therapeutic effectiveness? Ann Intern Med 1992; 117(11): 916–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chao C, Studts JL, Abell T. et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: how presentation of recurrence risk influences decision-making. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21(23): 4299–4305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Guyot P, Ades AE, Ouwens MJ, Welton NJ.. Enhanced secondary analysis of survival data: reconstructing the data from published Kaplan–Meier survival curves. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012; 12: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R. et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42(2): 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boutron I, Altman DG, Hopewell S. et al. Impact of spin in the abstracts of articles reporting results of randomized controlled trials in the field of cancer: the SPIIN randomized controlled trial. JCO 2014; 32(36): 4120–4126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Buffel du Vaure C, Boutron I, Perrodeau E, Ravaud P.. Reporting funding source or conflict of interest in abstracts of randomized controlled trials, no evidence of a large impact on general practitioners' confidence in conclusions, a three-arm randomized controlled trial. BMC Med 2014; 12: 69.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sashegyi A, Ferry D.. On the interpretation of the hazard ratio and communication of survival benefit. Oncologist 2017; 22(4): 484–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Estellat C, Faisy C, Colombet I. et al. French academic physicians had a poor knowledge of terms used in clinical epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol 2006; 59(9): 1009–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Krouss M, Croft L, Morgan DJ.. Physician understanding and ability to communicate harms and benefits of common medical treatments. JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176(10): 1565–1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zipkin DA, Umscheid CA, Keating NL. et al. Evidence-based risk communication: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2014; 161(4): 270–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Davis C, Naci H, Gurpinar E. et al. Availability of evidence of benefits on overall survival and quality of life of cancer drugs approved by European Medicines Agency: retrospective cohort study of drug approvals 2009–13. BMJ 2017; 359: j4530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hopewell S, Clarke M, Moher D. et al. CONSORT for reporting randomized controlled trials in journal and conference abstracts: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2008; 5(1): e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weir IR, Trinquart L.. Design of non-inferiority randomized trials using the difference in restricted mean survival times. Clin Trials 2018; 15(5): 499–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jagsi R, Guancial EA, Worobey CC. et al. The “gender gap” in authorship of academic medical literature–a 35-year perspective. N Engl J Med 2006; 355(3): 281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pit SW, Vo T, Pyakurel S.. The effectiveness of recruitment strategies on general practitioner's survey response rates—a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014; 14: 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Edwards PJ, Roberts I, Clarke MJ. et al. Methods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; MR000008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.