Abstract

Background

Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) as a disease entity distinct from invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) has merited focused studies of the genomic landscape, but those to date are largely limited to the assessment of early-stage cancers. Given that genomic alterations develop as acquired resistance to endocrine therapy, studies on refractory ILC are needed.

Patients and methods

Tissue from 336 primary-enriched, breast-biopsied ILC and 485 estrogen receptor (ER)-positive IDC and metastatic biopsy specimens from 180 ILC and 191 ER-positive IDC patients was assayed with hybrid-capture-based comprehensive genomic profiling for short variant, indel, copy number variants, and rearrangements in up to 395 cancer-related genes.

Results

Whereas ESR1 alterations are enriched in the metastases of both ILC and IDC compared with breast specimens, NF1 alterations are enriched only in ILC metastases (mILC). NF1 alterations are predominantly under loss of heterozygosity (11/14, 79%), are mutually exclusive with ESR1 mutations [odds ratio = 0.24, P < 0.027] and are frequently polyclonal in ctDNA assays. Assessment of paired specimens shows that NF1 alterations arise in the setting of acquired resistance. An in vitro model of CDH1 mutated ER-positive breast cancer demonstrates that NF1 knockdown confers a growth advantage in the presence of 4-hydroxy tamoxifen. Our study further identified a significant increase in tumor mutational burden (TMB) in mILCs relative to breast ILCs or metastatic IDCs (8.9% >20 mutations/mb; P < 0.001). Most TMB-high mILCs harbor an APOBEC trinucleotide signature (14/16; 88%).

Conclusions

This study identifies alteration of NF1 as enriched specifically in mILC. Mutual exclusivity with ESR1 alterations, polyclonality in relapsed ctDNA, and de novo acquisition suggest a role for NF1 loss in endocrine therapy resistance. Since NF1 loss leads to RAS/RAF kinase activation, patients may benefit from a matched inhibitor. Moreover, for an independent subset of mILC, TMB was elevated relative to breast ILC, suggesting possible benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Keywords: lobular, breast, ctDNA, estrogen receptor, tumor mutational burden, immune checkpoint inhibitors

Key Message

This study identifies an enrichment of NF1 loss of function alterations and high tumor mutational burden in metastatic, therapy-refractory ILC. Our findings reveal potential targeted interventions in this population, with possible sensitivities to RAS/RAF inhibition or immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Introduction

Invasive lobular breast cancer (ILC) is a distinct clinicopathological entity with relatively unique biologic behavior as compared with invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC). ILC carry a distinct morphologic phenotype which is linked to the genomic inactivation of e-cadherin as the sine qua non of this disease. Lobular carcinomas exhibit unique patterns of tumor growth, preferential sites of metastasis, differentially respond to endocrine therapy relative to IDC, can feature late disease relapses, and despite better prognostic factors have worse outcomes relative to ER-positive IDC [1–3].

Despite biologic differences, for both ILC and IDC the first-line treatment of advanced disease is endocrine therapy, including selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) such as tamoxifen and steroid or non-steroidal aromatase inhibitors (AIs). Recent evidence suggests that the management of acquired resistance to endocrine therapy can be informed by specific genomic changes, as exemplified by the mutations of the ligand binding domains of ESR1 and mutations of the PI3K/mTOR pathway leading to bypass resistance [4–6].

Studies to date have largely been limited to primary tumors rather than a post-treatment recurrence metastasis or liquid biopsy [7, 8]. In this study, we reviewed the genomic profiles of 180 metastatic ILCs (mILC) and 191 metastatic ER-positive IDC (mIDC) to investigate the genomic differences in advanced, progressive disease.

Methods

See also supplementary Methods, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Comprehensive genomic profiling

CGP was carried out in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified, CAP (College of American Pathologists)-accredited laboratory (Foundation Medicine Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA) on breast all-comers during the course of routine clinical care. Approval was obtained from the Western Institutional Review Board (Protocol No. 20152817). Hybrid capture was carried out for all coding exons from up to 395 cancer-related genes plus select introns from up to 31 genes frequently rearranged in cancer. We assessed all classes of genomic alterations (GA) including short variant, copy number, and rearrangement alterations, as described previously [9]. Liquid biopsy samples were processed as described previously [10]. Tumor mutational burden (TMB) was determined on 0.9–1.1 Mb as described previously [9, 11, 12]. Tumor loss of heterozygosity was determined as in Sun et al. [13].

Genomic trinucleotide signatures

Mutational signatures were called as described by Zehir et al. [14].

Competitive co-culture

Competitive co-culture of T47D shCntrl and T47D shECad was carried out as described previously [15].

Statistics and software

Statistics, computation, and plotting were carried out using Python 2.7 (Python Software Foundation) or R 3.4 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Univariate comparisons of proportion were made using a Fisher’s exact test. Multivariate comparisons of proportion were made with a Kruskal–Wallis test. Error bars on proportions were generated using a binomial confidence interval. Continuous distributions were compared using a non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test.

Results

Genomic profiles of mILC

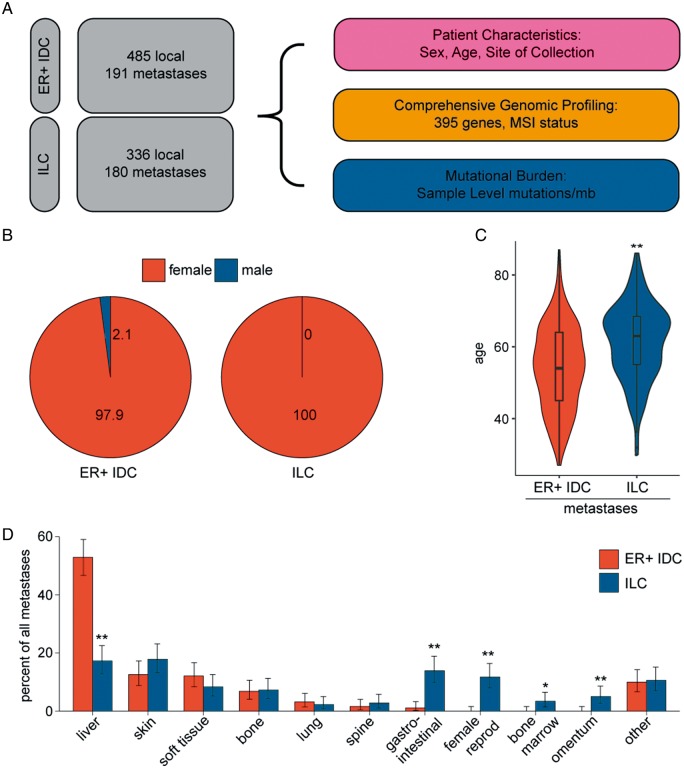

Comprehensive genomic profiling was carried out on 516 female ILC and 676 ER-positive IDC patients (2/676 male) in the course of clinical care (Figure 1A and B). The site of the specimens assayed was breast for 336 ILC and 485 ER-positive IDC cases, and assorted metastatic sites for 180 ILC and 191 ER-positive IDC cases. ER status was not available for the majority of ILC cases, but previous studies have placed the fraction ER-positive at 93%–99% [7, 16, 17]. Median age was higher in mILC patients relative to mIDCs (63 versus 54; Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) metastases are found at unique tissue sites. (A) Schematic of experimental design. In total, 676 estrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast invasive ductal carcinomas (IDCs) and 516 breast ILCs were profiled in the course of routine clinical care. Patient gender (B) and age (C) were compared in the metastatic ER-positive IDC and metastatic ILC cohorts. (D) Sites of metastatic biopsy were analyzed in the ER-positive IDC and ILC cohorts. P-values were calculated using the Mann–Whitney U test (C) and the Fisher’s exact test (D). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

In assessing sites of metastatic specimens in this study, ER-positive IDC metastases are frequently observed in the liver (53% of biopsies), in contrast to ILCs (17%, P = 7e−10) (Figure 1D). The latter were more frequently observed in the female reproductive tissues, GI tract, omentum, and bone marrow (12%, 14%, 5%, and 3%; P = 1e−07, P = 8e−07, P = 0.001, P = 0.012, respectively).

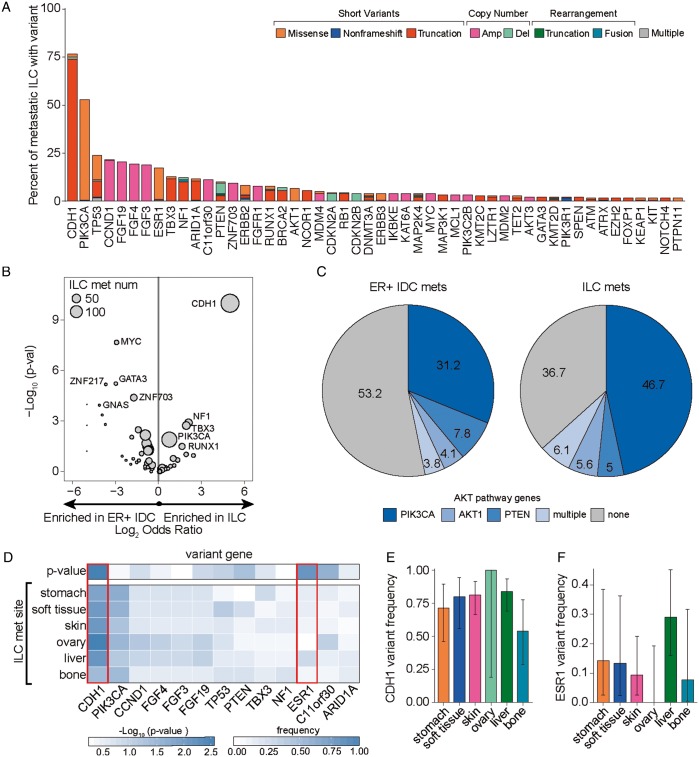

The most common GAs in mILC affected CDH1 (77%), PIK3CA (53%), TP53 (24%), the co-amplified 11q13 locus genes CCND1 (22%), FGF19 (21%), FGF4 (19%), FGF3 (19%), and ESR1 (17%) (Figure 2A). Alterations in CDH1 were predominantly frameshift and nonsense point mutations (87%), but also included point mutations at splice sites (9%), missense mutations (2%), and homozygous deletions (1%).

Figure 2.

Metastatic invasive lobular carcinomas (ILCs) exhibit a unique genomic profile. (A) Waterfall plot showing the frequency of known/likely alterations in metastatic ILCs broken down by variant class and further subdivided by the specific alteration type in the variant class. The short variant category of alterations included missense mutations, nonframeshifting indels, and truncations (frameshifting indels, splice-affecting, nonsense, nonstart); the copy number variant category of alterations included amplifications and deletions; the rearrangement variant category included truncations and fusions; and the multiple variants category included samples with more than one variant in the sample. (B) Volcano plot comparing the frequency of gene alterations in metastatic ILCs and estrogen receptor (ER)-positive metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) cohorts. P-values and odds ratios were calculated using the Fisher’s exact test. P values were capped at 1 × 10-10 and log2 odds ratios were capped at ±5. (C) Pie graph showing the frequency of known or likely AKT pathway alterations in the ER-positive metastatic IDC and metastatic ILC cohorts. Patients with multiple alterations are grouped in ‘multiple’. (D) The frequency of top-altered genes was compared across ILC metastatic sites with at least 10 samples and plotted as a heatmap. To determine whether alteration frequencies differed across sites, a Kruskal–Wallis test was applied. Genes that significantly differ across sites (CDH1 and ESR1; P < 0.01) are boxed in red and plotted in panels (E) and (F), respectively. For panels (E) and (F), error bars represent the 90% binomial confidence interval.

Comparison of genes differentially altered between mILC and mIDC identified 18 such genes after multiple hypothesis correction (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online; Figure 2B; analyses were carried out at a gene level for all known/likely alterations). Other than CDH1 (76% versus 6.8%, P < 5e−47), three genes were enriched in mILC versus mIDC: NF1 (12.2% versus 3.1%, P < 0.0013), TBX3 (12.8% versus 3.7%, P < 0.0019), and PIK3CA (52.8% versus 39.8%, P < 0.013). Genes most enriched in IDC were as follows: MYC (23.6% versus 3.9%, P < 2e−8), GATA3 (15.2% versus 2.2%, P < 6e−6), FGFR1 (18.3% versus 7.8%, P < 0.003), and TP53 (37.2% versus 23.9%, P < 0.007). Additionally, genes in the PI3K/mTOR pathway (PIK3CA, AKT1, PTEN) are significantly enriched for alteration in mILC (63.3% versus 46.8%; P < 0.001; Figure 2C).

Previous studies have shown an enrichment of ERBB2 short variants in CDH1-mutant advanced lobular carcinomas [18]. While the overall frequency of ERBB2 alterations was slightly higher in mIDCs versus mILCs (13.3% versus 8.3%), ERBB2 short variants were more common in mILCs [7.8% versus 2.6%, odds ratio (OR) = 3, P = 0.032].

We assessed whether there were differences in GA frequencies in ILCs found at different metastatic sites (Figure 2D). Most GAs were present at similar frequencies across all sites examined. Only CDH1 and ESR1 significantly differed in frequency between metastatic sites (Figure 2D–F). CDH1 GA frequency was lowest in bone versus all other sites (54%). ESR1 GA frequency was highest in the liver (29%) and never observed in the ovary (0%).

Metastatic ILCs exhibit higher frequency of NF1 genetic alterations

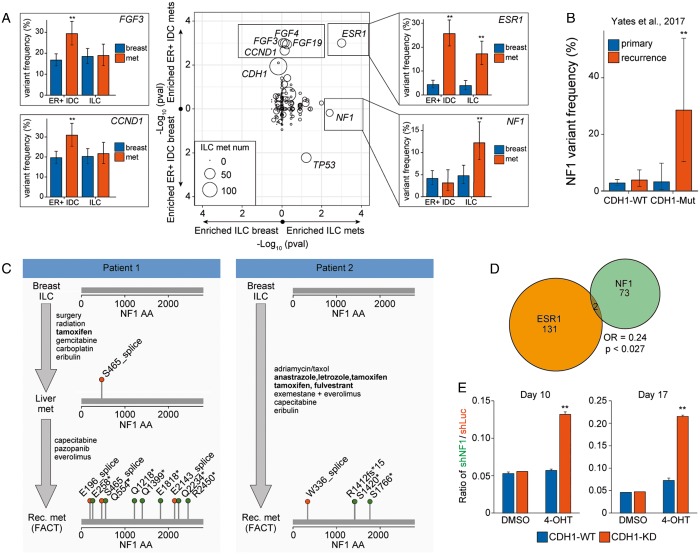

In examining the frequency of GA in breast disease and in distant metastases in each disease (ER-positive IDC and ILC) (Figure 3A; supplementary Tables S2 and S3, available at Annals of Oncology online), alterations of ESR1 were enriched in both mILC and mIDC, (Figure 3A). These alterations were predominantly within the ligand binding pocket, with 81% of the alterations (67/83) affecting amino acids 536–538. Additional alterations were amplifications (8.4%) and the E380Q alteration (10.8%).

Figure 3.

NF1 alterations are frequently identified in metastatic invasive lobular carcinomas (ILCs) and may drive endocrine therapy resistance. (A) Gene variant frequencies were compared between local breast ILC and metastatic breast ILC (x-axis) and between local ER-positive breast invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) and metastatic ER-positive breast IDC (y-axis). Plotted is the Fisher’s exact P-value (center). Alteration frequencies were plotted for a subset of significant genes (left and right panels) broken down by group (local versus met and ER-positive IDC versus ILC). Error bars represent the binomial 90% confidence interval. (B) NF1 alteration frequencies in the primary and recurrent breast cohorts from Yates et al. were calculated in CDH1-WT and CDH1-Mutant populations. Error bars represent the 90% binomial confidence interval. (C) Treatment and NF1 mutational status for two patients. Endocrine therapies are bolded. (D) Venn diagram examining the mutual exclusivity of ESR1 and NF1 in the entire breast cohort. Odds ratios and P-values were calculated using the Fisher’s exact test. (E) Quantification of CDH1-WT or CDH1-KD cells following T47D co-mixing experiments. For each background, 2.5 × 104 T47D-shNF1-GFP cells and 4.75 × 105 T47D-mCherry cells were mixed and treated with solvent control or 4-OHT for 10 days or 17 days, and fraction of cells with GFP or mCherry were measured by flow cytometry analysis. Plotted is the ratio of GFP-positive cells to mCherry-positive cells for each condition. **P < 0.01 from the Fisher’s exact test (B) or Student’s t-test (E). FACT, FoundationACT.

For ILCs but not IDCs, NF1 GA were enriched in metastatic specimens (P = 0.004; 4.7% in breast ILC versus 12.2% in mILC) (Figure 3A). These alterations were primarily inactivating, consisting of truncating alterations (8/23; 34.8%), splice site alterations (4/23; 17.4%), copy number losses (2/23; 8.7%), and nonsense alterations (7/23; 30.4%). For the NF1 mutated mILC specimens where zygosity was assessable, 11/14 (79%) of NF1 alterations were homozygous [13]. NF1 GAs were mutually exclusive with ESR1 GAs across the breast dataset (P = 0.027; OR = 0.24; Figure 3D).

To confirm the NF1 GA enrichment in an independent dataset, we re-analyzed the local and recurrent cohorts from Yates et al. [19]. Using CDH1 alterations as a proxy to identify ILC cases, alterations of NF1 were specifically enriched in CDH1-mutant, recurrent disease (Figure 3B;P = 0.009 CDH1-mut recurrent versus CDH1-mut primary).

NF1 alterations are polyclonal in ctDNA assays and emerge following endocrine therapy

Thirty-three of 569 ILCs and IDCs assayed with a liquid ctDNA assay (FoundationACT; FACT) harbored NF1 alterations; of these, 5/33 (15%) had strong polyclonality as designated by three or more NF1 alterations. This polyclonality rate is similar to ESR1 in ctDNA profiled samples (10/96, 10% with ≥3 ESR1 alterations). In contrast, of 34 samples with a CDH1 alteration, all 34 harbored only one CDH1 variant. Limiting this analysis only to lobular carcinomas, 3/4 (75%) of NF1 altered cases exhibited polyclonality.

Clinical histories for four of these NF1-altered FACT cases (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online) were obtained, and all cases were treated with endocrine therapies. Two of these patients had multiple genomic profiling assays carried out demonstrating emergence of NF1 alteration after hormonal therapy treatment and resistance (Figure 3C).

NF1 alterations co-occur with CDH1 and AKT pathway alterations and may facilitate endocrine therapy resistance

To understand what pathways might cooperate with NF1, we carried out a co-occurrence analysis. In all ER-positive breast cancer, NF1 GA’s significantly co-occur with CDH1 inactivation (OR = 2.2, P = 0.049). In NF1-altered mILCs, we observe a significant co-occurrence with AKT1 individually (OR = 6.3, P = 0.008) and with PI3K/mTOR pathway genes (PTEN, AKT1, PIK3CA; OR = 4.2, P = 0.018). Of the 23 NF1-altered mILCs, 17 had a co-occurring CDH1 and AKT pathway alteration. Similarly, 3/3 (100%) of NF1-altered samples profiled with FACT had a co-occurring CDH1 and AKT pathway alteration.

In the Yates et al. metastatic/recurrent dataset, all (4/4) NF1- and CDH1- mutated cases harbored a co-occurring AKT pathway alteration (supplementary Table S5, available at Annals of Oncology online). The co-occurrence suggests that these pathways may provide necessary cross talk for the pathogenicity of NF1 GAs.

To assess whether NF1 alterations may potentiate endocrine therapy resistance when a CDH1 and AKT pathway alteration are already present, we reviewed six paired samples with a NF1 GA. Half (3/6, 50%) of cases had an acquired NF1 alteration appear in the second specimen, with the first older specimen being NF1 wildtype. In each of these latter three cases, the tumor had pre-existing alterations in CDH1 and an AKT pathway gene. Moreover, two of the three samples had an ESR1 alteration in the first sample – one with a subclonal ESR1 missense alteration (Y537C) and another with an ESR1 amplification. In both cases, the recurrent sample lost the ESR1 alteration while gaining an NF1 loss of function alteration (supplementary Table S6, available at Annals of Oncology online).

We directly tested the hypothesis that NF1 loss of function reduces sensitivity to endocrine therapy in an AKT-mutant background using a PIK3CAH1074R mutant breast cancer cell line (T47D) with or without concurrent knockdown of CDH1. In co-mixing experiments, NF1 knockdown enhanced the resistance of cancer cells to 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) treatment only when E-Cadherin was reduced (Figure 3E;P < 0.00001). CDH1/NF1-knockdown cells increased from 5% of the population to 13% after 10 days of treatment with 4-OHT and 21% after 17 days of treatment, outcompeting the wildtype population. Importantly, this competitive advantage was only observed in the presence of 4-OHT but not in the solvent control condition. While subtle (fourfold enrichment over 17 days), this demonstrates that in the appropriate context NF1 loss can potentiate a competitive growth advantage.

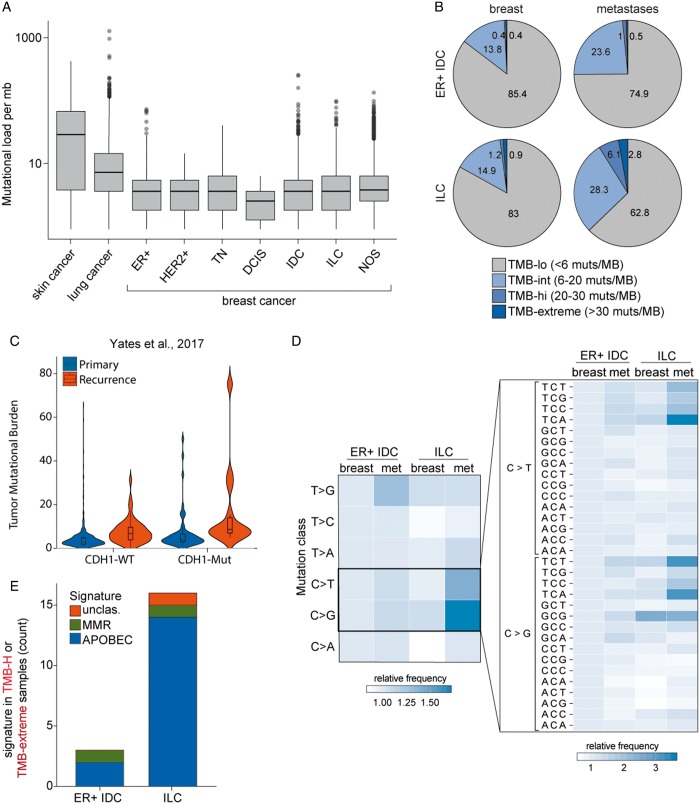

Metastatic ILCs exhibit an elevated TMB

Although breast cancers exhibit an overall low TMB in aggregate and across subtypes (Figure 4A), we examined TMB in ER-positive IDC and ILC split by disease site (breast versus metastatic). Few ER-IDC were TMB high (>20 muts/mb; 0.8% in breast, 1.6% in metastases; Figure 4B) and few breast-biopsied ILCs were TMB high (2.1%). Strikingly, mILC are frequently TMB high (8.9%, P = 0.0016 versus mIDC, P = 0.0006 versus primary/local ILC). In addition, 28.3% of mILC tumors have an intermediate TMB (6–20 muts/mb). Importantly, this population is independent of NF1 and ESR1 mutational statuses (P > 0.3). This finding raises the possibility that a significant subset of mILC may respond to immunotherapy.

Figure 4.

Metastatic invasive lobular carcinomas (ILCs) exhibit a significantly elevated tumor mutational burden. (A) Box and whisker plots capturing the spread of mutational burden (mutations per megabase) in skin cancers, lung cancers, and breast cancers broken down by histological or diagnostic subtype. All relevant tumors from the foundation medicine database were included in this analysis. (B) Pie charts showing the mutational burden for ER-positive IDCs and ILCs, broken down by local/met status. (C) Violin plots capturing the distribution of mutational burden (mutations per megabase) in primary and recurrent breast cohorts from Yates et al. in CDH1-WT and CDH1-Mutant populations. (D) The relative frequency of nucleotide substitutions was compared between ER-positive breast IDCs and breast ILCs broken down by primary met status. The left panel examines the mononucleotide change (e.g. C to G transversion mutations) while the right panel examines the trinucleotide context of the C>T and C>G alterations. (E) TMB-H samples (mutational load ≥20 muts/mb) were examined for trinucleotide mutational signatures, as described by Zehir et al. Identified signatures included MMR (mismatch repair) and AID/APOBEC.

We confirmed these findings in an independent dataset [19] (Figure 4C). Mutational burden was significantly higher in recurrent versus primary tumors (P < 0.0001) and in CDH1-mut versus CDH1-wt tumors (P = 0.0002). For the recurrent CDH1-mut cohort, 3/14 (21%) were TMB high and 8/14 (57%) were TMB intermediate.

Examining the genomic context of point mutations in all mILC cases, we observed a significant enrichment of C>T and C>G alterations (P = 7e−08 and P = 5e−14, respectively) particularly in the canonical APOBEC TCA and TCT contexts (Figure 4D; P < 1e−100). Consequently, mutational signature calling in TMB-high samples revealed that 14/16 (88%) of mILC samples had a dominant APOBEC signature (Figure 4E) [19]. Only two metastatic samples (one IDC and one ILC) harbored an MMR signature. Consistent with this, microsatellite-based testing of MMR demonstrates that almost all metastatic samples are microsatellite stable (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Discussion

This study identified NF1 alteration as a mechanism of acquired endocrine therapy resistance that is unique to ILC. NF1 GAs are common in mILCs, present at 12% frequency in our study and 29% in CDH1-altered recurrent breast carcinomas in Yates et al [19]. The mutual exclusivity with ESR1 mutation and chronologic emergence concurrent with relapse on endocrine therapy converge to support the notion of NF1 loss as such a mechanism of acquired resistance.

The specificity of NF1 alterations in mILC relative to mIDC may result from cross talk or cooperation with other pathways. NF1 loss is significantly co-occurrent with CDH1 and AKT pathway alterations; either or both of these may potentiate endocrine therapy resistance. An analysis of six paired samples showed that NF1 alterations appeared in the context of pre-existing CDH1 and AKT pathway alterations. Knockdown of NF1 in a PIK3CAH1074R line (T47D) enhances cell survival and/or proliferation more potently in the CDH1-KD background than in the CDH1-WT background. A previous study examining NF1 in glioma found that PI3K/AKT signaling was essential for NF1-mediated proliferation [20]. Other studies have shown NF1 cross talk with mTOR signaling [21]. Since NF1 functions at a key signaling node, more research will be required to understand the potential synergies that result in NF1-mediated therapy resistance.

NF1 loss leads to an activation of RAS by stabilizing the GTP-bound form, which suggests possible therapeutic strategies for recurrent ILCs. The MEK inhibitor selumetinib showed significant efficacy in pediatric patients with neurofibroma type 1-related PNs with response rates of 71% and is currently in phase II trials for adults with neurofibromatosis type 1 [22, 23].

Preclinical models of ILC have identified FGFR1 amplifications as regulators of cell growth and mediators of endocrine therapy resistance [24, 25]. While FGFR1 activates a number of pathways, including PI3K/AKT and Stats, RAS is a major target of FGFR1 signaling [26]. These findings suggest that activation of RAS pathway signaling, be it through FGFR1 amplification or NF1 loss, may confer endocrine therapy resistance in lobular carcinomas.

A main drawback of this study is our reliance on population-based alteration frequencies in local and metastatic disease instead of paired samples. Our study presents data from a limited number of paired samples (six paired solid samples; two paired FACT samples) which suggest a role of NF1 in endocrine therapy resistance. However, we cannot exclude other possibilities for the higher frequency of NF1 alterations in metastases. For instance, if NF1 alteration increased metastatic dissemination, a higher frequency of alterations may be observed in the metastases.

In this study, we identified an enrichment of high TMB in mILCs (9% versus 1%–2% overall). While a number of factors play a role in response to cancer immunotherapy, TMB appears to be an important determinant to response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICPI) [27]. The higher TMB in metastatic samples may be a result of longer tumor evolution or from accumulation of alterations from cytotoxic chemotherapy. It will be important to understand how this TMB high population overlaps with the subset of ILCs with high levels of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes, with tumors harboring an immune signature, and with the 17% of ILCs that stain positively for PD-L1 [7, 8, 28, 29].

Finally, there were relatively few genomic differences between local and recurrent breast cancers, with most differences falling in a select few resistance pathways. Similarly, despite distinct patterns of metastatic dissemination concordant with a previous study, only ESR1 and CDH1 exhibited potential site-specific tropism [30]. This suggests that the unique patterns of metastatic dissemination for ILCs are only partially explained by GAs.

In summary, this study provides insights into the mechanisms of resistance to endocrine therapy that are unique to ILC. Loss of function GA in NF1 is one such mechanism as is the acquisition of hypermutation that also carries an APOBEC signature. Further study and new clinical trials targeting NF1 in endocrine therapy resistant mILC appear warranted.

Funding

Dr Oesterreich’s studies on ILC are supported in part by BCRF, a Susan G Komen Leadership Award (SAC160073), and the Metastatic Breast Cancer Network (no grant number applies). Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01GM124491.

Disclosure

ESS, DXJ, GMF, JSR, JC, and SA are employees of Foundation Medicine Inc.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Note: This study was previously presented in part at SABCS 2017 as Highlighted Presentation # PD8-05.

References

- 1. Rakha EA, El-Sayed ME, Powe DG. et al. Invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast: response to hormonal therapy and outcomes. Eur J Cancer 2008; 44(1): 73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sikora MJ, Jankowitz RC, Dabbs DJ, Oesterreich S.. Invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast: patient response to systemic endocrine therapy and hormone response in model systems. Steroids 2013; 78(6): 568–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Metzger Filho O, Giobbie-Hurder A, Mallon E. et al. Relative effectiveness of letrozole compared with tamoxifen for patients with lobular carcinoma in the BIG 1-98 Trial. JCO 2015; 33(25): 2772–2779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Robinson DR, Wu YM, Vats P. et al. Activating ESR1 mutations in hormone-resistant metastatic breast cancer. Nat Genet 2013; 45(12): 1446–1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Toy W, Shen Y, Won H. et al. ESR1 ligand-binding domain mutations in hormone-resistant breast cancer. Nat Genet 2013; 45(12): 1439–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Merenbakh-Lamin K, Ben-Baruch N, Yeheskel A. et al. D538G mutation in estrogen receptor-alpha: a novel mechanism for acquired endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Cancer Res 2013; 73: 6856–6864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ciriello G, Gatza ML, Beck AH. et al. Comprehensive molecular portraits of invasive lobular breast cancer. Cell 2015; 163(2): 506–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Desmedt C, Zoppoli G, Gundem G. et al. Genomic characterization of primary invasive lobular breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34(16): 1872–1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Frampton GM, Fichtenholtz A, Otto GA. et al. Development and validation of a clinical cancer genomic profiling test based on massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nat Biotechnol 2013; 31(11): 1023–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clark TA, Chung JH, Kennedy M. et al. Analytical validation of a hybrid capture-based next-generation sequencing clinical assay for genomic profiling of cell-free circulating tumor DNA. J Mol Diagn 2018; 20(5): 686–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Forbes SA, Beare D, Gunasekaran P. et al. COSMIC: exploring the world's knowledge of somatic mutations in human cancer. Nucleic Acids Res 2015; 43(Database issue): D805–D811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chalmers ZR, Connelly CF, Fabrizio D. et al. Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden. Genome Med 2017; 9(1): 34.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sun JX, He Y, Sanford E. et al. A computational approach to distinguish somatic vs. germline origin of genomic alterations from deep sequencing of cancer specimens without a matched normal. PLoS Comput Biol 2018; 14(2): e1005965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zehir A, Benayed R, Shah RH. et al. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat Med 2017; 23(6): 703–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Feng YX, Sokol ES, Del Vecchio CA. et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition activates PERK-eIF2alpha and sensitizes cells to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cancer Discov 2014; 4(6): 702–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Arpino G, Bardou VJ, Clark GM, Elledge RM.. Infiltrating lobular carcinoma of the breast: tumor characteristics and clinical outcome. Breast Cancer Res 2004; 6: R149–R156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Colleoni M, Rotmensz N, Maisonneuve P. et al. Outcome of special types of luminal breast cancer. Ann Oncol 2012; 23(6): 1428–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ross JS, Wang K, Sheehan CE. et al. Relapsed classic E-cadherin (CDH1)-mutated invasive lobular breast cancer shows a high frequency of HER2 (ERBB2) gene mutations. Clin Cancer Res 2013; 19(10): 2668–2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yates LR, Knappskog S, Wedge D. et al. Genomic evolution of breast cancer metastasis and relapse. Cancer Cell 2017; 32(2): 169–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kaul A, Toonen JA, Cimino PJ. et al. Akt- or MEK-mediated mTOR inhibition suppresses Nf1 optic glioma growth. Neuro Oncol 2015; 17(6): 843–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brundage ME, Tandon P, Eaves DW. et al. MAF mediates crosstalk between Ras-MAPK and mTOR signaling in NF1. Oncogene 2014; 33(49): 5626–5636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bradford D, Whitcomb P, Dombi E. et al. Phase II trial of the MEK1/2 inhibitor selumetinib (AZD6244) in adults with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) and inoperable plexiform neurofibromas (PNs). J Clin Oncol 2016; 34(Suppl 15): TPS2596–TPS2596. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dombi E, Baldwin A, Marcus LJ. et al. Activity of selumetinib in neurofibromatosis type 1-related plexiform neurofibromas. N Engl J Med 2016; 375(26): 2550–2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sikora MJ, Cooper KL, Bahreini A. et al. Invasive lobular carcinoma cell lines are characterized by unique estrogen-mediated gene expression patterns and altered tamoxifen response. Cancer Res 2014; 74(5): 1463–1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reis-Filho JS, Simpson PT, Turner NC. et al. FGFR1 emerges as a potential therapeutic target for lobular breast carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12(22): 6652–6662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ahmad I, Iwata T, Leung HY.. Mechanisms of FGFR-mediated carcinogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012; 1823(4): 850–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A. et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science 2015; 348(6230): 124–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Oesterreich S, Lucas PC, McAuliffe PF. et al. Opening the door for immune oncology studies in invasive lobular breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2018; 110(7): 696–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thompson ED, Taube JM, Asch-Kendrick RJ. et al. PD-L1 expression and the immune microenvironment in primary invasive lobular carcinomas of the breast. Mod Pathol 2017; 30(11): 1551–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mathew A, Rajagopal PS, Villgran V. et al. Distinct pattern of metastases in patients with invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 2017; 77: 660–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.