Abstract

Background

Developing new methods to deliver cells to the injured tissue is a critical factor in translating cell therapeutics research into clinical use; therefore, there is a need for improved cell homing capabilities.

Materials and methods

In this study, we demonstrated the effects of labeling rat bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) with fabricated polydopamine (PDA)-capped Fe3O4 (Fe3O4@PDA) superparticles employing preassembled Fe3O4 nanoparticles as the cores.

Results

We found that the Fe3O4@PDA composite superparticles exhibited no adverse effects on MSC characteristics. Moreover, iron oxide nanoparticles increased the number of MSCs in the S-phase, their proliferation index and migration ability, and their secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor relative to unlabeled MSCs. Interestingly, nanoparticles not only promoted the expression of C-X-C chemokine receptor 4 but also increased the expression of the migration-related proteins c-Met and C-C motif chemokine receptor 1, which has not been reported previously. Furthermore, the MSC-loaded nanoparticles exhibited improved homing and anti-inflammatory abilities in the absence of external magnetic fields in vivo.

Conclusion

These results indicated that iron oxide nanoparticles rendered MSCs more favorable for use in injury treatment with no negative effects on MSC properties, suggesting their potential clinical efficacy.

Keywords: mesenchymal stem cells, migration, Fe3O4 nanoparticles, polydopamine

Introduction

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) hold great promise for the treatment of multiple diseases and disorders.1,2 Although MSCs are capable of high levels of ex vivo expansion and are already in clinical use for numerous applications,3–5 a significant challenge remains in their efficient delivery to target locations in order to enhance successful engraftment.6 This limitation is mainly evident when the therapeutic application requires MSCs to secrete factors immediately following injection.7 MSCs exhibit low efficiency in targeting injury or inflamed tissues.8 Targeting of MSCs to sites of inflammation/injury is mediated by crucial adhesion or homing ligands that bind to intercellular adhesion molecules or chemokine receptors (eg, C-X-C chemokine receptor 4 [CXCR4] and C-C motif receptor 1 [CCR1]).9,10 Additionally, expression of the hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)-receptor, c-Met, in MSCs promotes migration via the HGF/c-Met axis,11,12 however, the expression levels of these receptors are low or inconsistent in MSCs.13 Culture conditions can affect the expression of these receptors, and long-term culture can affect the homing ability of MSCs in vitro;14 therefore, several studies have suggested ways to transiently enhance MSC homing toward sites of inflammation.15 Previous studies reported enhanced homing efficiency by altering the cell surface through conjugation of specific antibodies or proteins;16,17 whereas others achieved similar results using retroviral vectors encoding homing receptors.18,19 However, the experimental procedures associated with these findings are very complicated. Iron oxide nanoparticles are conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents widely studied in recent years for their potential application in MSC labeling.20,21 Although studies suggest that labeling with iron oxide nanoparticles does not alter MSC viability, proliferation, or functional properties, the effect of such labeling remains controversial.22,23 Even though a previous study reported that iron oxide nanoparticles increased MSC migration,24 the associated mechanism remains unknown. Moreover, in vivo investigations are needed to clarify the effect of iron oxide nanoparticles on the specific migration of MSCs to inflammation sites. In addition, inconsistencies in the findings of several studies might be related to the sources of the MSCs used, nanoparticles size, surface-coating material, incubation time, transfection agent, and/or labeling methods.25

The Fe3O4 form of iron oxide nanoparticles is approved for use in clinical applications due to its pronounced bio-compatibility.26 These nanoparticles have garnered increased attention because of their unique response features to external magnetic fields (EMFs), making them suitable for use in MRI.27 Polydopamine (PDA) is highly biocompatible and biodegradable,28 and, therefore, widely used to coat nanoparticles for numerous biomedical applications.29,30 PDA-capped Fe3O4 (Fe3O4@PDA) and their composites are among the safest nanomaterials used for clinical diagnosis and therapy.31 Given the cell uptake necessary for cell therapeutics, the size and shape of the spherical, self-assembled structures comprising hundreds of nanoparticles (also known as superparticles) make them highly suitable for such applications.32 Additionally, PDA can spontaneously form a conformal layer through in situ polymerization in an alkaline dopamine solution.33

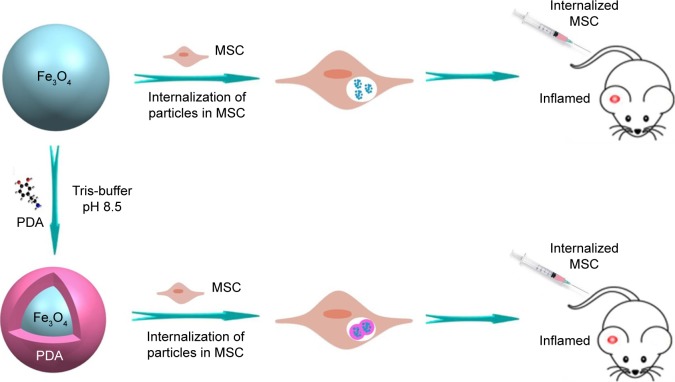

In this study, we fabricated Fe3O4@PDA composite super-particles by employing preassembled Fe3O4 nanoparticles as the core and PDA as the shell, with the PDA coating further improving the physiological stability and biocompatibility of the Fe3O4 superparticles. In vitro experiments indicated that the Fe3O4@PDA composite superparticles exhibited no adverse effects on MSC characteristics and increased the number of MSCs in the S-phase, their proliferation index and migration ability, and their secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Additionally, these represent the first findings of nanoparticles not only promoting CXCR4 expression,24 but also increasing levels of the migration-related proteins c-Met and CCR1 in MSCs. Although some studies showed that noninvasive EMFs can increase nanoparticle-internalized MSC homing following an intra-arterial or intravenous injection,34–36 there have been no reports showing a similar effect in the absence of EMFs in vivo. However, static magnetic fields can affect MSC viability,34 proliferation,37 differentiation capacity,38 colony formation,39 and extracellular vesicle secretion.40 Our results validated the hypothesis that iron oxide nanoparticles can improve MSC homing and internalization, and promote rapid directional movements following intravenous injection and in the absence of EMFs (Figure 1), suggesting their potential clinical efficacy.

Figure 1.

Research design.

Notes: Synthesis and internalization of Fe3O4 @PDA and Fe3O4. Rats with inflammation in the right ear received 106 MSCs labeled with Fe3O4@PDA or Fe3O4 via the tail vein.

Abbreviations: Fe3O4@PDA, PDA-capped Fe3O4; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; PDA, polydopamine.

Materials and methods

Preparation and characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles

Nanoparticles were prepared as previously described.31 Briefly, SDS-capped Fe3O4 nanoparticles were fabricated by emulsification.32,41 Under mechanical stirring and nitrogen atmosphere at room temperature, 4.0 mL of 7.0 mg/mL oleic acid-stabilized Fe3O4 nanoparticles were injected into SDS aqueous solution (12.5 mL; 14 mg/mL). After ultrasonic treatment, the emulsion was heated at 60°C to evaporate toluene and obtain SDS-capped Fe3O4 superparticles. Tris-buffer (12 mL) was added to the prepared Fe3O4 nanoparticle and superparticle solution, and the pH was adjusted to 8.5, followed by the addition of different volumes of 0.03 M dopamine solution. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature (22°C–26°C) for 3 hours while the solution color gradually turned dark brown, indicating in situ polymerization of dopamine. The Fe3O4@PDA nanoparticles were obtained by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes and washed with deionized water.

MSC isolation and expansion

Bone marrow-derived MSCs from rats were obtained by their adherence to the culture plate. MSCs were cultured in DMEM/nutrient mixture F-12 Ham (DMEM/F12) supplemented with 10% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and maintained at 37°C with saturated humidity and 5% CO2. After 48 hours, non-adherent cells were removed by washing, and the medium was changed twice weekly. MSCs were sub-cultured at 80% confluence following the treatment with 0.05% trypsin and 0.02% EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St Louis, MO, USA) for 3 minutes at 37°C. The cells were washed and harvested by centrifugation at 1,000 rpm for 5 minutes, followed by replating at a lower density (1,000 cells/cm2).

Flow cytometric characterization of MSCs

Passage 3 MSCs were trypsinized and washed twice with PBS, followed by incubation with antibodies against CD44-phycoerythrin (PE), CD34-PE, CD90-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), and CD45-FITC (all from BD Bio-sciences, San Jose, CA, USA) in the dark for 30 minutes at 4°C. After incubation, the cells were washed twice with PBS, fluorescence intensity was measured using flow cytometry (FC500; Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, CA, USA), and the data were analyzed with CXP software (Beckman Coulter Inc.).

MSC differentiation potential

Adipogenesis

MSCs (5×104 cells/cm2) were seeded onto a 12-well plate with DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS, followed by the addition of adipogenic differentiation medium (StemPro adipogenesis differentiation kit; Thermo Fisher Scientific) on the second day. Unstimulated MSCs cultured in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS were used as staining control. The cultures were refed every 3–4 days, and after 21 days, the cells were stained with Oil Red O (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) and evaluated using an optical microscope (X51; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Osteogenesis

MSCs (5×104 cells/cm2) were seeded onto a 12-well plate with DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS. Osteogenic differentiation medium (StemPro osteogenesis differentiation kit; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to the cells on the second day after attachment to the bottom of the petri dish. Unstimulated MSCs were cultured in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS and used as staining control. The cultures were refed every 3–4 days and after 35 days, cells were stained with 2% Alizarin Red S solution (Alizarin staining kit; Genmed, Shanghai, China) and subjected to examination using an optical microscope (X51; Olympus Corporation).

MSC labeling with Fe3O4@PDA or Fe3O4

Prussian blue staining

Iron oxide nanoparticles were added to the MSCs in DMEM/F12 expansion media (without FBS) supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution and incubated for 2 hours, after which the cells were allowed to recover in fresh media (10% FBS) for 14 hours. Cells were then washed twice with PBS, labeled with Fe3O4@PDA or Fe3O4, and stained with a Prussian blue iron stain kit (Beijing Solarbio Science and Technology, Co. Ltd., Beijing, China) according to manufacturer instructions.

Fe quantification in MSCs

For a typical sample, 0.1 mL of the cell suspension was digested overnight using 0.3 mL of concentrated nitric acid (~70%) and 0.1 mL hydrogen peroxide (30%). Samples were then diluted to a volume of 10 mL with deionized water, yielding a final nitric acid concentration of 2%. Iron concentration was determined by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES) using a PerkinElmer Optima 3300DV system (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Iron oxide nanoparticles (100 µg/mL) were detected using a Hitachi H-800 electron microscope (Hitachi Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at an acceleration voltage of 200 kV with a charge-coupled device camera. MSCs were labeled with Fe3O4@PDA or Fe3O4 (50 µg/mL) for 16 hours and washed twice with PBS. MSCs were then fixed in phosphate-buffered Karnofsky’s solution, followed by staining with 2% osmium tetroxide at 4°C overnight, dehydration using graded ethanol, and embedding in Epon 812 resin. Resin blocks were sectioned using a microtome, doubly stained with uranyl acetate and lead hydroxide, and imaged using a Tecnai Spirit system (120 kV; FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA).

Effect of nanoparticle labeling on MSC properties

Viability study

MSCs (~5×104) were seeded in a 96-well plate 24 hours before the experiment, after which iron oxide nanoparticles (0, 25, 50, 75, 100, 150, or 200 µg/mL) dispersed in media were added to the plates and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. The cells were collected using 0.05% trypsin and counted, with each concentration determined in triplicate.

Proliferation assessment

MSCs (~2×106) were labeled with 50 µg/mL of iron oxide nanoparticles as described for the viability study. MSCs were then seeded on plates at 5,000 cells/cm2, and at each time point (days 1, 3, and 5) MSCs in the plates were estimated by measuring the OD at 450 nm (OD450) using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). Data are shown as mean of three independent biological replicates. Data obtained from MSCs grown under standard conditions were used for comparison.

Differentiation and surface marker assays

Cells labeled with iron oxide nanoparticles were detected and imaged for differentiation potential. Fluctuations in MSC-associated surface markers following treatment with the magnetic particle for 24 hours were assessed by flow cytometry as described.

Colony-forming unit (CFU) assay

MSCs (60/well) were seeded in 6-well plates in medium supplemented with 10% FBS for 21 days, after which cells were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes and stained with Giemsa (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) for 10 minutes at room temperature. Excess stain was removed with distilled water. Colonies were observed and counted, with a colony defined as an aggregate of >40 cells.

In vitro migration assay

In a 24-well Transwell plate (FluoroBlok, 8.0 µm colored polyester membrane; BD Biosciences), complete medium supplemented with 10% FBS was added to the (bottom) wells, and ~30,000 MSCs labeled with Fe3O4@PDA or Fe3O4 and purified by Ficoll-Paque (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) isolation were seeded into the insert in media containing 1% FBS. After 16 hours of incubation at 5% CO2 and 37°C, inserts were washed twice with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E; Sigma-Aldrich Co.) for 10 minutes, and counted.

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total cellular RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA integrity was verified by electrophoresis using ethidium bromide staining and determining the OD260:OD280 ratio. Total RNA (500 ng) was reverse transcribed using 2.5 U avian myeoloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase extra large, 10 U RNase inhibitor, 1 mM deoxy-ribonucleotide triphosphate mixture, 1.25 pmoL Oligo dT-Adaptor primer, 5 mM MgCl2, and 1× reverse transcription buffer (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Shiga Prefecture, Japan) according to manufacturer’s instructions. A no amplification control lacking reverse transcriptase was included. Reactions were incubated at 42°C for 30 minutes, followed by 5 minutes at 95°C, and 5 minutes at 5°C. Approximately 25 ng of cDNA was used in qRT-PCR with SYBR Green PCR master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 0.2 µM of gene-specific forward and reverse primers (Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The thermo-cycler parameters used for amplifying these genes were as follows: one cycle at 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 seconds, −55°C for 15 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds. A list of the primers used is presented in Table 1. qRT-PCRs were performed in triplicate in the ABI StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Quantitative measurements from all data were obtained using the 2−ΔΔCt method with normalization against β-actin mRNA levels.

Table 1.

Primer sequences and product sizes

| Symbol | Primer sequences | Product sizes (bp) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| β-Actin | F-GCGGCAGTGGCCATCTCTT | 151 |

| R-CTGGCCGGGACCTGACAGA | ||

| CCR1 | F-GGCCCTAGCCATCTTAGCTT | 108 |

| R-GTCTTCAGGCTCTCATCGGG | ||

| c-Met | F-TCTGTGCGTTCCCCATCAAA | 102 |

| R-GCTCGTGGTTGGGTCCATAA | ||

| CXCR4 | F-AGGAACTGAACGCTCCAGAA | 125 |

| R-AACCACACAGCACAACCAAA | ||

| COX-2 | F-AGACAGATCAGAAGCGAGGACCTG | 155 |

| R-ATACACCTCTCCACCGATGACCTG | ||

| IL-10 | F-AAAGCAAGGCAGTGGAGCAG | 151 |

| R-AGTAGATGCCGGGTGGTTCA | ||

| TGF-β | F-GGCACCATCCATGACATGAACCG | 148 |

| R-GCCGTACACAGCAGTTCTTCTCTG | ||

| TNF-α | F-GCCACGAGCAGGAATGAGAAGAG | 103 |

| R-GCGATGTGGAACTGGCAGAGG | ||

Abbreviations: CCR1, C-C motif receptor 1; c-Met, cellular-mesenchymal to epithelial transition factor; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; CXCR4, C-X-C chemokine receptor 4; IL-10, interleukin-10; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α.

Western blot

After treatment with iron oxide nanoparticles, MSCs were washed with PBS and lysed in ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing a complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich Co.). Primary antibodies against CXCR4, CCR1, c-Met, and histone H3 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) were purchased and used according to manufacturer’s recommendations, with histone H3 used as an internal control. An equal amount of protein (50 µg) for each sample was loaded onto a 12% SDS gel subjected to electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), which was blocked for 1 hour at room temperature with 5% nonfat dry milk in PBS containing 1% Tween-20 and incubated with primary antibodies for CCR1, c-Met, CXCR4, and histone H3 (1:1,000, 1:1,000, 1:500, and 1:2,000, respectively) overnight at 4°C. After washing, the membrane was incubated with a fluorescently labeled secondary antibody (1:5,000; Thermo Fisher Scientific) at room temperature for 1 hour and visualized using the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA).

Cell cycle assay

MSCs incubated with iron oxide nanoparticles were collected, washed, and suspended in cold 75% ethanol overnight at 4°C. After fixation, cells were pelleted, washed with PBS, and stained using 50 µg/mL propidium iodide (PI) and 50 µg/mL RNase A (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Jiangsu, China) dissolved in 0.5 mL PBS. The suspension was incubated in the dark for 30 minutes at 37°C, after which the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. The S-phase fraction (SPF) was calculated as follows: SPF = S/(G0/G1 + S + G2/M)×100%. The proliferation index (PIndex) was calculated as follows: PIndex = (S + G2/M)/(G0/G1 + S = G2/M)×100%.42

Cell apoptosis assay

After incubation with iron oxide nanoparticles, MSCs were harvested, rinsed twice with PBS, and suspended in 500 µL binding buffer. The suspended MSCs were incubated for 15 minutes at 4°C with 5 µL annexin V-FITC solution, followed by incubation for another 5 minutes at 4°C after adding 10 µL of PI solution. The emitted green fluorescence of annexin-V and red fluorescence of PI were detected by flow cytometry at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and emission wavelengths of 525 nm and 575 nm, respectively. For each sample, 10,000 events were recorded. The amount of early apoptosis, late apoptosis, and necrosis was determined as the percentage of annexin-V+/PI−, annexin-V+/PI+, and annexin-V-/PI+ cells, respectively.

ELISA

The supernatants from MSCs incubated with iron oxide nanoparticles and MSCs alone were collected at 24, 72, and 120 hours, with each sample assayed in triplicate. Soluble VEGF and TGF-β were measured using a rat VEGF and TGF-β ELISA kit (Elabscience, Wuhan, China), according to manufacturer’s instructions. Photometric measurements were conducted at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc.).

Animals

Pathogen-free male Wistar rats (6 weeks old) were purchased from the Institute of Laboratory Animal Sciences (Beijing, China) and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. Rats were allowed to adapt to the experimental conditions for 1 week before starting the experiment. All experimental animal protocols were approved by the Welfare and Research Ethics Committee on Animal Experiments of Jilin University. The animal experiments were carried out following the internationally accepted animal care guidelines (EEC Directive of 1986; 86/609/EEC).

In vivo ear inflammation model

Hairs from the ears of rats were removed using depilatory cream, and the right ears were inflamed using Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Sigma-Aldrich Co.) as previously described.43 Briefly, rats were sedated and administered a single injection of 240 µg LPS in PBS (8 mg/mL) into the base of the right ear. Similarly, 30 µL of PBS was injected into the base of the left ear as a control. Before injection, MSCs were incubated with iron oxide nanoparticles and cultured for 24 hours. Untreated and nanoparticle-treated MSCs were stained using 5 µM 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindodicarbocyanine (DiD) tracer (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) according to manufacturer instructions. A one-time, tail vein injection of 1×106 MSCs (ie, untreated or nanoparticle-treated) per rat was administered. The right ears of the rats were imaged 24 hours after MSC injection using a CellviZio intravital microscope (Mauna Kea Technologies, Paris, France).

Histology and Prussian blue analysis

Ear-tissue samples from all groups were excised and fixed in 4% formalin until use. All samples were embedded at the hedge in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) (OCT compound; Tissue-Tek®; Sakura Finetek USA, Inc., Torrance, CA, USA) and instantly frozen in liquid nitrogen. Slides were obtained by cutting the ear block with a cryostat at −20°C. For H&E staining, slides were thawed, hydrated, washed, and stained with an H&E staining kit (Sigma-Aldrich Co.). Images were captured with a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). The slides were stained with Prussian blue iron stain kit (Beijing Solarbio Science and Technology, Co. Ltd) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (v 17.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon and Mann–Whitney U tests) were used for statistical analysis. Parametric data are expressed as the mean ± SD, (n=3). Statistical significance was defined as a P<0.05.

Results and discussion

Preparation and characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles

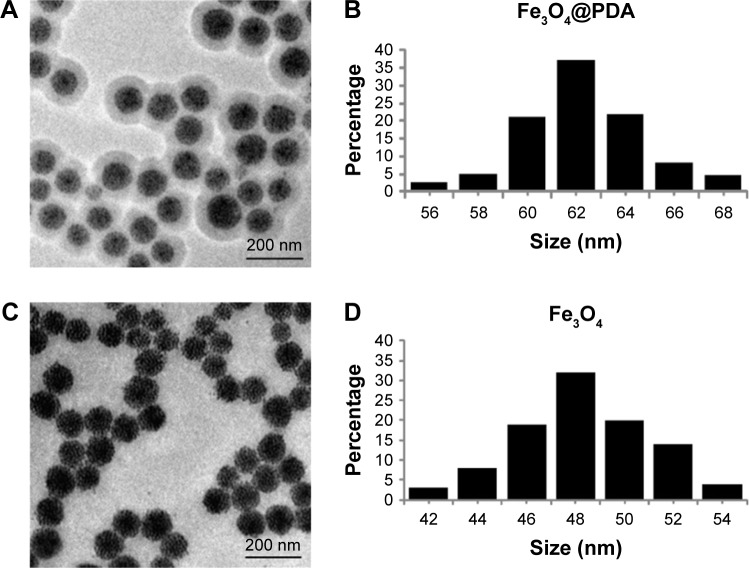

Fe3O4@PDA nanoparticles were prepared by coating preassembled Fe3O4 nanoparticles with a PDA shell. Figure 2A and C shows a typical TEM image of the Fe3O4@PDA and Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Because nanoparticles larger than 100 nm can scarcely penetrate cells by cellular phagocytosis, Fe3O4 nanoparticles with an average diameter of 48.3 nm were designated as the cores used to prepare Fe3O4@PDA nanoparticles.44 Figure 2B and D shows the size distributions of Fe3O4@PDA and Fe3O4 nanoparticles that were <100 nm. These results of electron microscopy analysis allowed synthesis of appropriately sized nanoparticles for labeling cells.

Figure 2.

TEM image and size distribution of iron oxide nanoparticles.

Notes: (A and C) are TEM images of representative 100 µg/mL Fe3O4@PDA and Fe3O4 nanoparticles, respectively. (B and D) are the size distribution of Fe3O4@PDA and Fe3O4 nanoparticles, respectively.

Abbreviations: Fe3O4@PDA, PDA-capped Fe3O4; PDA, polydopamine; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

Due to the collective effect of the preassembled Fe3O4 nanoparticles, utilization of a PDA shell greatly enhanced the superparamagnetism, physiological stability, and biocompatibility of the Fe3O4 core.31 The high degree of aggregation of Fe3O4 nanoparticles frequently reduces Brownian motion and precludes cellular uptake of the aggregates due to their size.45 Accordingly, PDA encapsulation reduced Fe3O4 aggregation and increased their uptake by cells. These results implied the potential efficacy of the Fe3O4@PDA complex for use in biological applications.

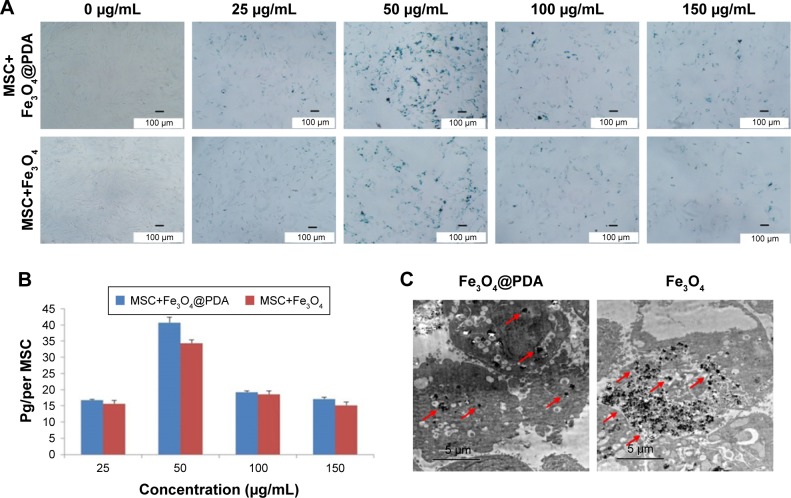

MSC labeling with Fe3O4@PDA or Fe3O4

To investigate the efficiency of nanoparticle entry into MSCs, we performed Prussian blue staining of MSCs (Figure 3A). ICP-OES results indicated that 50 mg/mL nanoparticles resulted in the highest cellular uptake efficiency among the four different concentrations tested (Figure 3B) and that the labeling efficiency of 50 µg/mL Fe3O4@PDA was higher than that of Fe3O4. Figure 3C shows TEM images of the MSCs after 16 hours of incubation with Fe3O4@PDA or Fe3O4 nanoparticles. These results suggested that PDA-encapsulated Fe3O4 nanoparticles exhibited an increased capacity for uptake by MSCs, as well as better biocompatibility than Fe3O4 based on morphological assessment of the MSCs following uptake.

Figure 3.

Iron oxide nanoparticle internalization by MSCs.

Notes: Different concentrations of nanoparticles (0, 25, 50, 100, and 150 µg/mL) were labeled MSCs for 16 hours to determine the optimal labeling efficiency. (A) Then MSCs were stained with a Prussian blue iron stain kit. The scale bar is 100 µm. (B) Iron concentration was determined by ICP-OES. (C) TEM image of nanoparticles (50 µg/mL) internalized in a MSC. The scale bar is 5 µm. The red arrows indicate that nanoparticles were observed in the cell cytoplasm.

Abbreviations: Fe3O4@PDA, PDA-capped Fe3O4; PDA, polydopamine; ICP-OES, inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

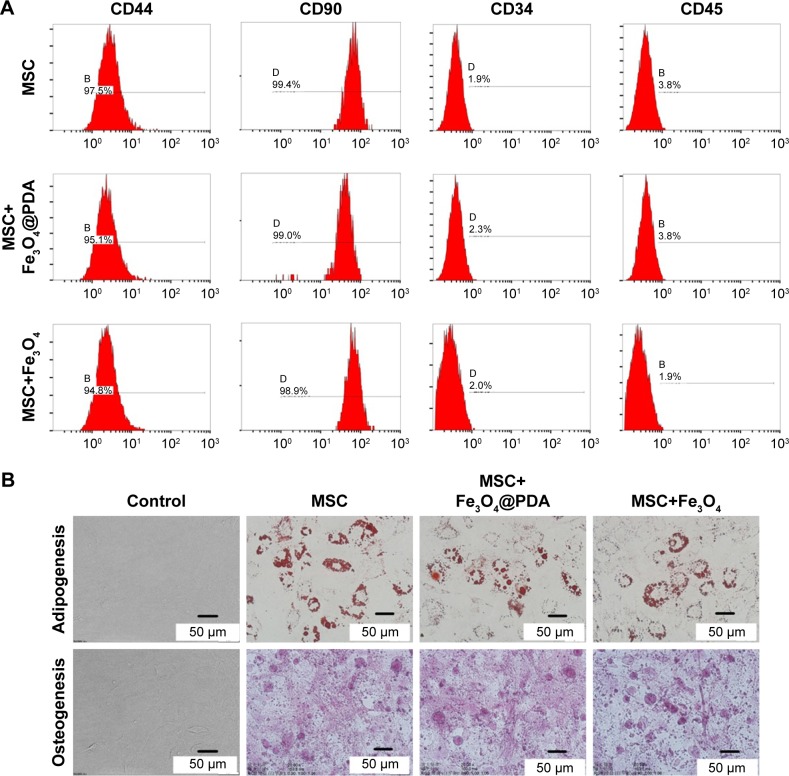

Characterization of MSCs loaded with iron oxide nanoparticles

Most cultured adherent cells exhibited a fibroblastic morphology characteristic of MSCs. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting of MSCs loaded with iron oxide nanoparticles indicated that they were negative for CD45 and CD34 surface markers while strongly expressing typical surface antigens, such as CD44 and CD90 (Figure 4A). To confirm whether nanoparticle-labeled MSCs could differentiate into two lineages (ie, osteogenic and adipogenic), we performed differentiation assays. When cultured in the appropriate medium, the cells differentiated into adipocytes or osteoblasts (Figure 4B), respectively, with no differences observed between their respective controls. Numerous studies have described flow cytometric evaluation of MSC surface markers in order to assess the differentiation potential of MSCs following nanoparticle internalization.35,45–49 In agreement with our findings, their results consistently reported no effects on surface-marker expression or osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation ability. These results showed that nanoparticle-labeling did not alter MSC differentiation or characteristics.

Figure 4.

Characterization of MSCs was not influenced by iron oxide nanoparticles.

Notes: A total of 50 µg/mL nanoparticles were labeled MSCs for 16 hours. (A) FACS analysis of MSC-labeled iron oxide nanoparticles showed that they were negative for CD45 and CD34, and strongly expressed typical surface antigens, such as CD44 and CD90. (B) Differentiation of MSC-labeled iron oxide nanoparticles: cultured in appropriate differentiation media, MSCs differentiated into adipocytes or osteoblasts. All exhibited adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation potential similar to that of control MSCs.

Abbreviations: FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; Fe3O4@PDA, PDA-capped Fe3O4; PDA, polydopamine; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell.

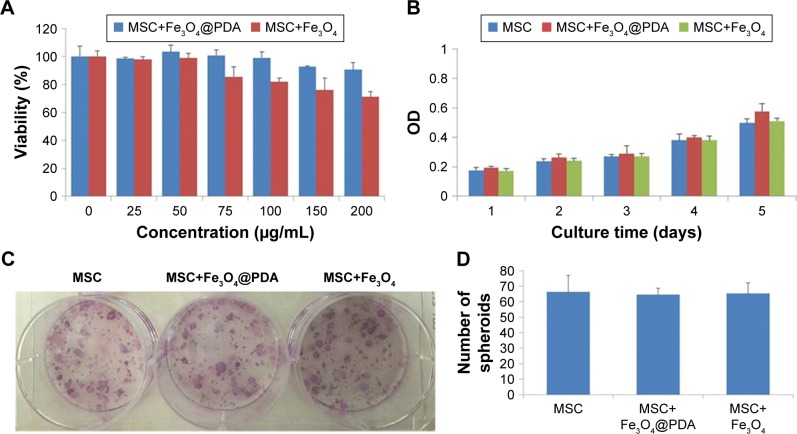

Effect of iron oxide nanoparticles on MSC viability and proliferation

Nanoparticles used to label MSCs for cell-based therapeutic approaches should not compromise MSC survival and proliferation; therefore, we investigated the viability and proliferation of nanoparticle-labeled MSCs. We found that MSC uptake of 50 µg/mL nanoparticles did not affect cell viability (Figure 5A). Additionally, although concentrations higher than 50 µg/mL did not enhance cell-uptake efficiency, at 100 µg/mL, the nanoparticles tended to aggregate in the culture medium and adhere to the plate. Moreover, we generally observed gradually reduced cell viability at >50 µg/mL Fe3O4 nanoparticles, whereas MSCs viability in the presence of Fe3O4@PDA was less strongly affected according to concentration. These findings suggested that Fe3O4@PDA nanoparticles displayed better biocompatibility relative to that observed in the presence of Fe3O4 nanoparticles. To assess potential effects on MSC proliferation, we evaluated this characteristic at 5 days post-labeling with both nanoparticles. A cell counting kit-8 assay demonstrated that MSCs labeled with both types of nanoparticles showed similar proliferation rates as compared to the control (Figure 5B). Moreover, CFU assay is based on the principle that a single MSC when cultured in medium will undergo proliferation to produce distinct colonies. The CFU assay results indicated that labeled MSCs plated at low density were able to form colonies (Figure 5C and D). These results demonstrated that MSCs labeled with nanoparticles at a concentration of 50 µg/mL exhibited normal proliferative activity.

Figure 5.

Proliferation and viability of MSCs are not affected by nanoparticle labeling.

Notes: Cell viability assay was observed in MSCs labeled with different concentrations (0, 25, 50, 75, 100, 150, or 200 µg/mL) of nanoparticles for 24 hours. (A) Proliferation of 50 µg/mL nanoparticle-labeled MSCs was assessed after 5 days by CCK-8. (B) In vitro CFU assays are usually used to detect the proliferation and differentiation features of MSCs. A colony was defined as an aggregate of >40 cells. (C) CFU colonies of MSC-labeled nanoparticles (50 µg/mL) were stained with Giemsa stain, (D) and the number of colonies was counted.

Abbreviations: CCK-8, cell counting kit-8; CFU, colony-forming unit; Fe3O4@PDA, PDA-capped Fe3O4; PDA, polydopamine; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell.

Previous reports indicated that labeling with Fe3O4 nanohybrids increases MSC viability,42 whereas use of commercial iron oxide nanoparticles (ie, magnetic iron oxide beads) reduces viability.45 In the present study, we observed similar rates of MSC proliferation as those of unlabeled control MSCs, which agreed with previously reported results,50–53 however, some previous studies indicated that uptake of iron oxide nanoparticles stimulated in vitro MSC proliferation but reduced CFU.54,55 These conflicting results might be associated with differences in nanoparticles size, shape, surface modification, incubation concentration, and time.

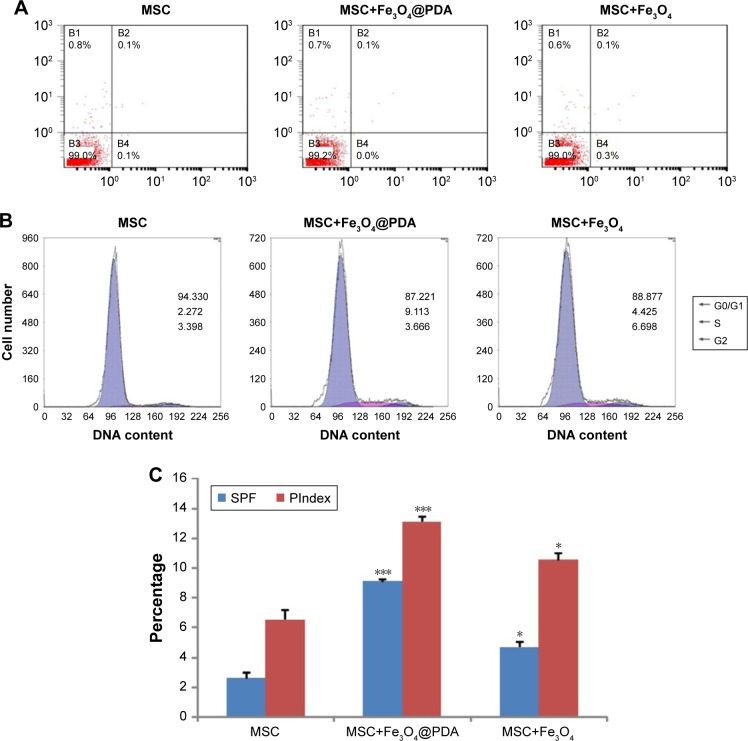

Uptake of iron oxide nanoparticles increase MSC SPF and PIndex

To determine whether nanoparticle labeling induces MSC apoptosis, we examined labeled MSCs using annexin V and PI double staining. As shown in Figure 6A, we observed no increases in the percentage of apoptotic nanoparticle-labeled MSCs relative to control MSCs. Additionally, cell cycle analysis showed a higher percentage of Fe3O4@PDA-labeled MSCs in the S-phase relative to controls and that this percentage was slightly higher in MSCs loaded with Fe3O4 (Figure 6B). Moreover, nanoparticle labeling significantly increased the SPF and PIndex of MSCs relative to unlabeled MSCs (Figure 6C), with these values larger for Fe3O4@PDA-labeled MSCs than those for Fe3O4-labeled MSCs. The results of our cell cycle analyses agreed with those reported previously,54,56 and indicated that cell cycle progression was unaffected by nanoparticle labeling.

Figure 6.

Uptake of iron oxide nanoparticles did not induce apoptosis but increased MSC SPF and PIndex.

Notes: MSCs were cultured for 16 hours in the presence or absence of 50 µg/mL iron oxide nanoparticles. At harvest, the MSCs were stained with antibodies to annexin V and PI, and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) The FACS plots were representative of one of the three experiments. The DNA content of the MSCs was measured by PI staining using flow cytometry. (B) The FACS plots were representative of one of the three experiments. (C) The SPF and PIndex of three independent experiments were averaged. Bar represent the SD. *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001, vs the MSCs group.

Abbreviations: FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; Fe3O4@PDA, PDA-capped Fe3O4; PDA, polydopamine; PI, propidium iodide; PIndex, proliferation index; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; SPF, S-phase fraction.

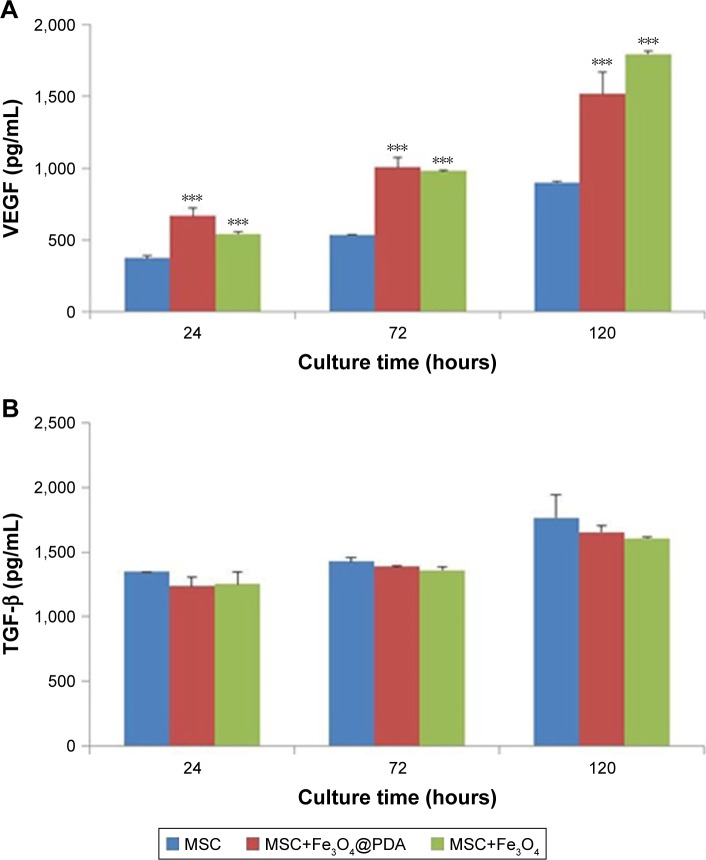

Cytokine release from MSCs labeled with iron oxide nanoparticles

To examine cytokine release from MSCs labeled with iron oxide nanoparticles, we analyzed the release of VEGF and TGF-β. Cells were incubated with 50 µg/mL of iron oxide nanoparticles, and ELISA was used to measure cytokine release after 24, 72, and 120 hours. We found no clear differences in the TGF-β release between MSCs labeled with iron oxide nanoparticles and control MSCs, however, there was a significant and time-dependent increase in VEGF release in MSCs labeled with the nanoparticles as compared to controls (Figure 7). Cytokines such as VEGF can promote neovascularization of injured tissue.32 VEGF-mediated angiogenesis also is a critical determinant of the increased cellular tumorigenicity.57 However, VEGF alone is not sufficient to promote cell tumorigenicity, suggesting that additional angiogenic factors and cytokines (such as TGF-β, tumor necrosis factor-α [TNF-α], interleukin-6 [IL-6]) regulated in their expression also are critical for an effective tumor initiation.58–60 Additionally, MSC-specific VEGF expression appears to be tightly regulated based on physiological need, and may represent a superior means of inducing therapeutic angiogenesis.61,62 Therefore, MSCs labeled with iron oxide nanoparticles might be advantageous to repairing damaged tissues.

Figure 7.

Cytokine release of MSCs labeled with iron oxide nanoparticles.

Notes: The MSCs were labeled with 50 µg/mL iron oxide nanoparticles for 16 hours. And MSC alone cultures were collected at the time points of 24, 72, and 120 hours. Standard cell culture medium served as a control. (A) VEGF and (B) TGF-β concentrations were measured by ELISA. Bar represent the SD. ***P<0.001, vs the MSCs group.

Abbreviations: Fe3O4@PDA, PDA-capped Fe3O4; PDA, polydopamine; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

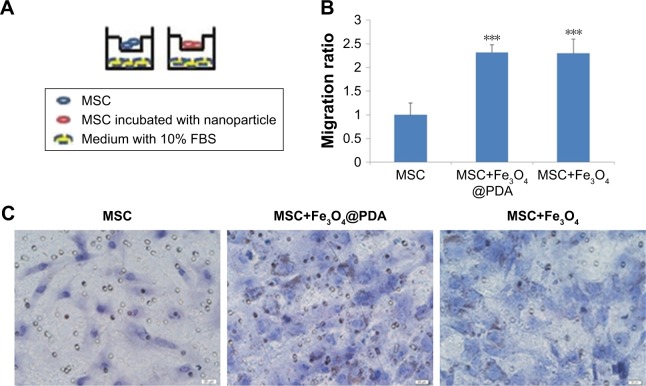

Labeling with iron oxide nanoparticles promotes MSC migration in vitro

We examined MSC migration in vitro using a Transwell migration assay. MSCs in the presence or absence of nanoparticles in media supplemented with 1% FBS were seeded on an insert adjacent to chambers containing complete media with 10% FBS (Figure 8A). Evaluation of migration potential revealed a significant difference in the number of migrated cells between control MSCs (22±5 cells) and MSCs labeled with iron oxide nanoparticles (50±3 and 49±6) (Figure 8B and C; P<0.001). These results showed that labeling with iron oxide nanoparticles increased MSC migration in agreement with previous reports,63 suggesting that these labeled MSCs might be suitable for promoting rapid migration to injury sites.

Figure 8.

Effect of nanoparticle exposure on MSC migration in vitro.

Notes: The migration of MSCs labeled with 50 µg/mL nanoparticles for 16 hours. (A) Schematic illustration of the Transwell assay. (B) The migratory capacity after nanoparticle labeling is displayed as the histogram of the ratio of migrated cells. Bar represent the SD. ***P<0.001, vs the MSCs group. (C) MSCs passed through the inserts were dyed by H&E. Scale bar =20 µm.

Abbreviations: Fe3O4@PDA, PDA-capped Fe3O4; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; PDA, polydopamine; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell.

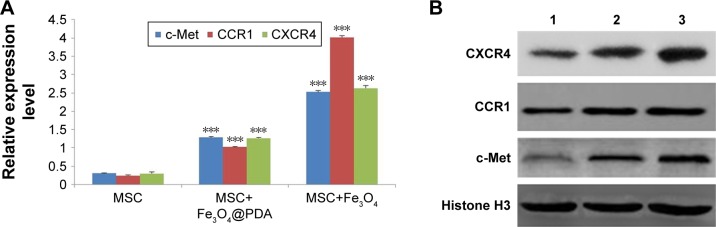

Labeling with iron oxide nanoparticles increases c-Met, CCR1, and CXCR4 expressions in MSCs

Homing capacity is a critical characteristic of therapeutic MSCs, with homing ability mediated by specific chemokine receptors, including CXCR4, CCR1,64 and the tyrosine kinase receptor c-Met.65 In the present study, we determined whether iron oxide nanoparticles could regulate the expression of these receptors by qRT-PCR analysis of c-Met, CCR1, and CXCR4 mRNA levels, finding that they were significantly increased in MSCs following iron oxide nanoparticle uptake (Figure 9A, P<0.001). Western blot subsequently confirmed significant elevations in the levels of the cell-surface receptors c-Met and CCR1 in these MSCs (Figure 9B). These results were consistent with studies showing that labeling with iron oxide nanoparticles improved CXCR4 expression in MSCs,24,66 demonstrating the efficacy for the enhanced homing ability of nanoparticle-labeled MSCs in the absence of an EMF. Moreover, increased CXCR4 levels in nanoparticle-labeled MSCs might promote the CXCR4/stromal-cell-derived-1 signaling pathway at the injured area.50 Furthermore, CCR1 reportedly mediate MSC homing,64 and CCR1 overexpression enhances MSC migration, survival, and engraftment.19 Additionally, upregulated c-Met expression enhanced MSC migration to injury sites.12 It is the first finding that nanoparticles increased the levels of the migration-related proteins c-Met and CCR1 in MSCs. Meanwhile, our results suggested that nanoparticle-labeled MSCs might display improved homing to inflammatory sites.

Figure 9.

Expression of migration-related genes analyzed by qRT-PCR and Western blot.

Notes: The mRNA level of migration-related genes from the MSCs labeled with 50 µg/mL iron oxide nanoparticles for 16 hours was measured by qRT-PCR. (A) The column charts represent the qRT-PCR data. The data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ***P<0.001 when compared to MSCs. (B) MSCs which were labeled with 50 µg/mL iron oxide nanoparticles for 16 hours expressed protein level of migration-related genes. 1 represents MSCs group; 2 represents MSCs labeled with Fe3O4@PDA group; 3 represents MSCs labeled with Fe3O4 group.

Abbreviations: CCR1, C-C motif receptor 1; c-Met, cellular-mesenchymal to epithelial transition factor; CXCR4, C-X-C chemokine receptor 4; Fe3O4@PDA, PDA-capped Fe3O4; PDA, polydopamine; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; qRT, quantitative reverse transcription.

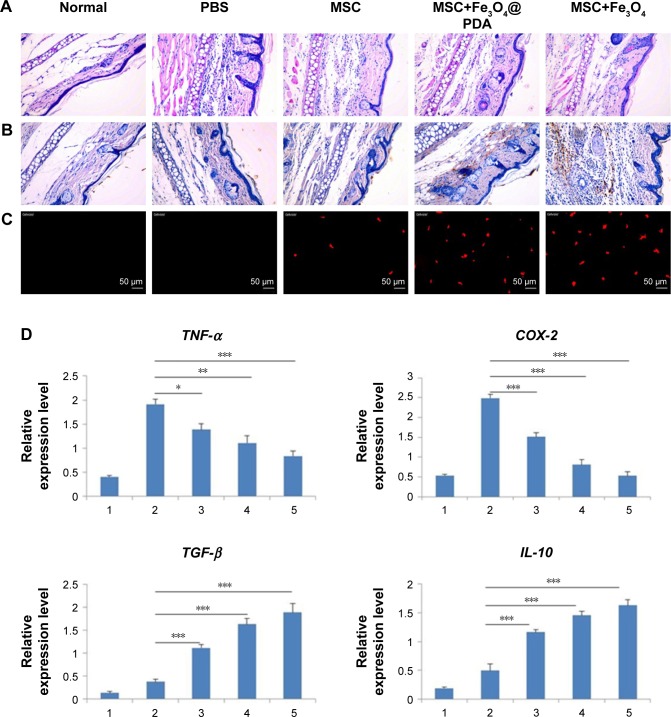

In vivo homing ability of labeled MSCs in an inflammatory ear model

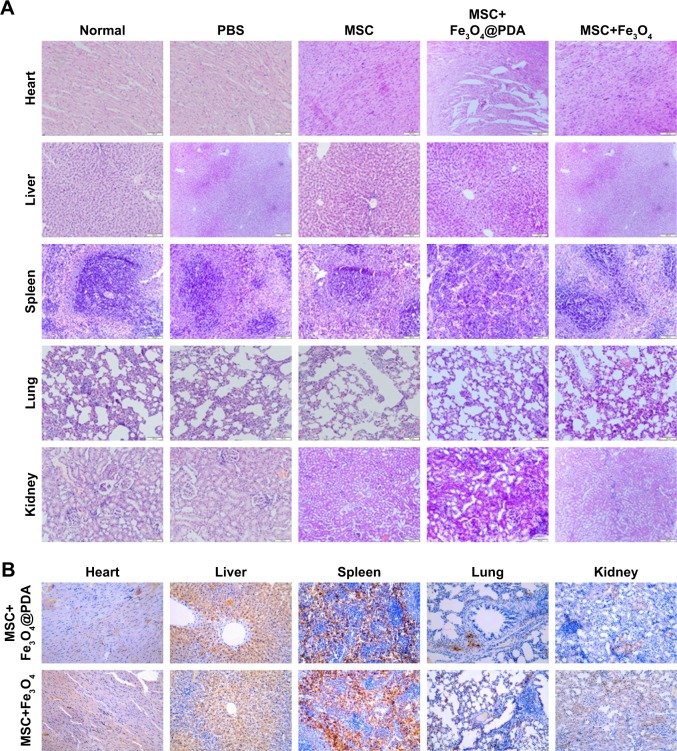

In vitro migration assays (Figure 8) indicated that nanoparticle labeling affected MSC migration. Because homing of systemically administered MSCs can be influenced by factors not accounted for in our in vitro assay, including shear stress, immune system interference, and endothelial barriers,67 we investigated the influence of iron oxide nanoparticles on the translocation ability of MSCs in vivo to a distant site of inflammation in a rat injury model. To facilitate cell imaging, unlabeled MSCs and MSCs labeled with iron oxide nanoparticles (>97% labeling efficiency) were infused with the cell-tracker dye DiD via the tail vein. Macroscopic observations of the ear were performed using H&E staining, which showed gross signs of improvement in rats treated with nanoparticle-labeled MSCs relative to the unlabeled MSCs and PBS-treated control groups, and the PBS-treated control group showed greater neutrophil infiltration and edema as compared to the groups treated with MSCs (Figure 10A). Prussian blue staining showed minimal levels of iron deposition in the inflamed ears (Figure 10B) and Figure 10C shows that increased MSC translocation was observed in the inflamed ears of rats treated with nanoparticle-labeled MSCs relative to MSCs. Consistent with other studies,68 MSCs were detectable at inflamed sites as quickly as 24 hours following injection. Our results suggested that the iron oxide nanoparticles could also increase the migratory capacity of the MSCs in the absence of EMFs in vivo. Furthermore, H&E staining of major organs at 24 hours after MSC injection showed undamaged organs (Figure 11A) and Prussian blue staining showed minimal iron deposition in the heart, lung, and kidney as well as positive staining for iron deposition in the liver and spleen (Figure 11B).

Figure 10.

Reduction of inflammation following nanoparticle-treated MSC administration.

Notes: (A) Histological analysis of ear tissues (scale bars: 100 µm). The sections showed an alteration of tissue architecture in the inflamed ears and in the ones treated with MSCs. (B) Prussian blue analysis of ear sections at 24 hours reveals that iron oxide nanoparticles stayed at ear tissues. Scale bars: 100 µm. Moreover, nanoparticles treatment enhanced the recruitment of MSCs in the inflamed ear. (C) Nanoparticles labeled MSCs exhibited a significant addition in ear compared to the other groups. Scale bars: 20 µm. (D) qRT-PCR for the expressions of pro-(TNF-α and COX-2) and anti-(TGF-β and IL-10) inflammatory genes on explants 24 hours following the injection of MSCs labeled with iron oxide nanoparticles and unlabeled MSCs. The expression levels of pro-inflammatory molecules found in the inflamed ears are also shown for control ear with no inflammation. (n=3; bar represent the SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001). 1 represents normal ear with no inflammation; 2 represents inflamed ears injected with PBS; 3 represents inflamed ears injected with MSC; 4 represents inflamed ears injected with MSCs labeled with Fe3O4@PDA; and 5 represents inflamed ears injected with MSCs labeled with Fe3O4.

Abbreviations: COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; Fe3O4@PDA, PDA-capped Fe3O4; IL-10, interleukin-10; PDA, polydopamine; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; qRT, quantitative reverse transcription; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α.

Figure 11.

The rat’s major organ slices 24 hours after the injection of nanoparticle-labeled MSCs were stained using (A) H&E and (B) Prussian blue. The scale bar is 100 µm.

Abbreviations: Fe3O4@PDA, PDA-capped Fe3O4; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; PDA, polydopamine; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell.

In vivo molecular analysis

Concomitant with MSC retention at sites of inflammation, reduced expressions of the pro-inflammatory genes TNF-α and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) were observed according to qRT-PCR analysis of explanted ears at 24 hours postinjection (Figure 10D). Data showed that the expression of such genes decreased in MSCs labeled with iron oxide nanoparticles but was comparable between Fe3O4- and Fe3O4@PDA-labeled groups. Moreover, the expression of such genes in tissues injected with control MSCs was higher than that observed in tissues injected with nanoparticle-labeled MSCs. Concurrently, a statistically significant increase in the expression of anti-inflammatory genes (TGF-β and IL-10) was observed in tissues injected with MSCs (Figure 10D), with TGF-β levels higher in nanoparticle-labeled MSCs and IL-10 expression 25- and 12-fold higher relative to levels in control-treated ears.

Additionally, MSC recruitment and accumulation within the inflamed ear led to a decreased expression of pro-inflammatory markers, agreeing with previous finding.69 H&E staining following systemic administration demonstrated that nanoparticle-treated MSCs produced anti-inflammatory effects in vivo. Furthermore, increased IL-10 and TGF-β expressions in the inflamed ears following treatment validated these findings at the molecular level. It is likely that the significant reduction in local inflammation following systemic administration of nanoparticle-labeled MSCs was dependent upon rapid localization of MSCs to the inflamed site. These data confirmed that the uptake of iron oxide nanoparticles improved the homing capacity and therapeutic efficacy of MSC-based therapies.

Conclusion

In this study, in vitro and in vivo experiments demonstrated that MSCs internalize iron oxide nanoparticles with no adverse effects on MSC viability and proliferation, suggesting their biocompatibility with the MSCs. Moreover, MSC labeling with these nanoparticles increased MSCs SPF and PIndex, as well as VEGF secretion, and promoted MSC migration through the upregulation of c-Met, CCR1, and CXCR4 levels, thereby increasing their ability to systemically translocate to sites of inflammation in the absence of EMFs. These results demonstrated that iron oxide nanoparticles promoted MSC migration to sites of inflammation, thereby suggesting the potential clinical efficacy of this method.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Jilin Provincial Department of Finance Project of China (No 3D516P803430).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Česen Mazič M, Girandon L, Kneževič M, Avčin SL, Jazbec J. Treatment of severe steroid-refractory acute-graft-vs.-host disease with mesenchymal stem cells–single center experience. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2018;6:93. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2018.00093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daneshmandi S, Karimi MH, Pourfathollah AA. TGF-β engineered mesenchymal stem cells (TGF-β/MSCs) for treatment of Type 1 diabetes (T1D) mice model. Int Immunopharmacol. 2017;44:191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2017.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnhoorn M, de Jonge-Muller E, Molendijk I, et al. Endoscopic administration of mesenchymal stromal cells reduces inflammation in experimental colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(8):1755–1767. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahn SY, Chang YS, Sung DK, Sung SI, Park WS. Hypothermia broadens the therapeutic time window of mesenchymal stem cell transplantation for severe neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):7665. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25902-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xia H, Liang C, Luo P, et al. Pericellular collagen I coating for enhanced homing and chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells in direct intra-articular injection. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9(1):174. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0916-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karp JM, Leng Teo GS. Mesenchymal stem cell homing: the devil is in the details. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(3):206–216. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy O, Zhao W, Mortensen LJ, et al. mRNA-engineered mesenchymal stem cells for targeted delivery of interleukin-10 to sites of inflammation. Blood. 2013;122(14):e23–e32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-495119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Bahr L, Batsis I, Moll G, et al. Analysis of tissues following mesenchymal stromal cell therapy in humans indicates limited long-term engraftment and no ectopic tissue formation. Stem Cells. 2012;30(7):1575–1578. doi: 10.1002/stem.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu Y, Zhao RC. The role of chemokines in mesenchymal stem cell homing to myocardium. Stem Cell Rev. 2012;8(1):243–250. doi: 10.1007/s12015-011-9293-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hocking AM. The role of chemokines in mesenchymal stem cell homing to wounds. Adv Wound Care. 2015;4(11):623–630. doi: 10.1089/wound.2014.0579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vogel S, Trapp T, Börger V, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor-mediated attraction of mesenchymal stem cells for apoptotic neuronal and car-diomyocytic cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67(2):295–303. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0183-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu J, Pan G, Liang T, Huang P. HGF/c-Met signaling mediated mesenchymal stem cell-induced liver recovery in intestinal ischemia reperfusion model. Int J Med Sci. 2014;11(6):626–633. doi: 10.7150/ijms.8228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Becker A, Riet IV. Homing and migration of mesenchymal stromal cells: how to improve the efficacy of cell therapy? World J Stem Cells. 2016;8(3):73–87. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v8.i3.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou P, Liu Z, Li X, et al. Migration ability and Toll-like receptor expression of human mesenchymal stem cells improves significantly after three-dimensional culture. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;491(2):323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.07.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naderi-Meshkin H, Bahrami AR, Bidkhori HR, Mirahmadi M, Ahmadiankia N. Strategies to improve homing of mesenchymal stem cells for greater efficacy in stem cell therapy. Cell Biol Int. 2015;39(1):23–34. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy O, Mortensen LJ, Boquet G, et al. A small-molecule screen for enhanced homing of systemically infused cells. Cell Rep. 2015;10(8):1261–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.01.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dykstra B, Lee J, Mortensen LJ, et al. Glycoengineering of E-selectin ligands by intracellular versus extracellular fucosylation differentially affects osteotropism of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2016;34(10):2501–2511. doi: 10.1002/stem.2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brenner S, Whiting-Theobald N, Kawai T, et al. CXCR4-transgene expression significantly improves marrow engraftment of cultured hematopoietic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2004;22(7):1128–1133. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2003-0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang J, Zhang Z, Guo J, et al. Genetic modification of mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing CCR1 increases cell viability, migration, engraftment, and capillary density in the injured myocardium. Circ Res. 2010;106(11):1753–1762. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.196030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, Xu F, Zhang C, et al. High MR sensitive fluorescent magnetite nanocluster for stem cell tracking in ischemic mouse brain. Nanomedicine. 2011;7(6):1009–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riegler J, Liew A, Hynes SO, et al. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle targeting of MSCs in vascular injury. Biomaterials. 2013;34(8):1987–1994. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen CH, Lin YS, Fu YC, et al. Electromagnetic fields enhance chondrogenesis of human adipose-derived stem cells in a chondrogenic microenvironment in vitro. J Appl Physiol. 2013;114(5):647–655. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01216.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saha S, Yang XB, Tanner S, Curran S, Wood D, Kirkham J. The effects of iron oxide incorporation on the chondrogenic potential of three human cell types. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2013;7(6):461–469. doi: 10.1002/term.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang X, Zhang F, Wang Y, et al. Design considerations of iron-based nanoclusters for noninvasive tracking of mesenchymal stem cell homing. ACS Nano. 2014;8(5):4403–4414. doi: 10.1021/nn4062726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qi Y, Feng G, Huang Z, Yan W. The application of super paramagnetic iron oxide-labeled mesenchymal stem cells in cell-based therapy. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40(3):2733–2740. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2364-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee N, Hyeon T. Designed synthesis of uniformly sized iron oxide nanoparticles for efficient magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41(7):2575–2589. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15248c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sundstrøm T, Daphu I, Wendelbo I, et al. Automated tracking of nanoparticle-labeled melanoma cells improves the predictive power of a brain metastasis model. Cancer Res. 2013;73(8):2445–2456. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis ME, Chen ZG, Shin DM. Nanoparticle therapeutics: an emerging treatment modality for cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(9):771–782. doi: 10.1038/nrd2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang R, Wang S, Yang Y, et al. Modification of polydopamine-coated Fe3O4 nanoparticles with multi-walled carbon nanotubes for magnetic-µ-dispersive solid-phase extraction of antiepileptic drugs in biological matrices. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2018;410(16):3779–3788. doi: 10.1007/s00216-018-1047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Y, Zhang F, Wang Q, et al. The synthesis of LA-Fe3O4@PDA-PEG-DOX for photothermal therapy-chemotherapy. Dalton Trans. 2018;47(7):2435–2443. doi: 10.1039/c7dt04080f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ge R, Li X, Lin M, et al. Fe3O4@polydopamine Composite Theranostic Superparticles Employing Preassembled Fe3O4 Nanoparticles as the Core. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(35):22942–22952. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b07997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang X, Xu X, Li T, et al. Composite photothermal platform of polypyrrole-enveloped Fe3O4 nanoparticle self-assembled superstructures. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6(16):14552–14561. doi: 10.1021/am503831m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bi D, Zhao L, Yu R, et al. Surface modification of doxorubicin-loaded nanoparticles based on polydopamine with pH-sensitive property for tumor targeting therapy. Drug Deliv. 2018;25(1):564–575. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2018.1440447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang J, Xiang B, Deng J, Freed DH, Arora RC, Tian G. Inhibition of viability, proliferation, cytokines secretion, surface antigen expression, and adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells by seven-day exposure to 0.5 T static magnetic fields. Stem Cells International. 2016;2016(4):1–12. doi: 10.1155/2016/7168175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meng Y, Shi C, Hu B, et al. External magnetic field promotes homing of magnetized stem cells following subcutaneous injection. BMC Cell Biol. 2017;18(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s12860-017-0140-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qi Y, Yang Z, Ding Q, Zhao T, Huang Z, Feng G. Targeted transplantation of iron oxide-labeled, adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells in promoting meniscus regeneration following a rabbit massive meniscal defect. Exp Ther Med. 2016;11(2):458–466. doi: 10.3892/etm.2015.2944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim EC, Leesungbok R, Lee SW, et al. Effects of moderate intensity static magnetic fields on human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Bioelectromagnetics. 2015;36(4):267–276. doi: 10.1002/bem.21903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amin HD, Brady MA, St-Pierre JP, Stevens MM, Overby DR, Ethier CR. Stimulation of chondrogenic differentiation of adult human bone marrow-derived stromal cells by a moderate-strength static magnetic field. Tissue Eng Part A. 2014;20(11–12):1612–1620. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schäfer R, Bantleon R, Kehlbach R, et al. Functional investigations on human mesenchymal stem cells exposed to magnetic fields and labeled with clinically approved iron nanoparticles. BMC Cell Biol. 2010;11(1):22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-11-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marędziak M, Marycz K, Śmieszek A, Lewandowski D, Toker NY. The influence of static magnetic fields on canine and equine mesenchymal stem cells derived from adipose tissue. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2014;50(6):562–571. doi: 10.1007/s11626-013-9730-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bai F, Wang D, Huo Z, et al. A versatile bottom-up assembly approach to colloidal spheres from nanocrystals. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46(35):6650–6653. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang H, Qu S, Li S, et al. Silencing SATB1 inhibits proliferation of human osteosarcoma U2OS cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2013;378(1–2):39–45. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1591-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Corradetti B, Taraballi F, Martinez JO, et al. Hyaluronic acid coatings as a simple and efficient approach to improve MSC homing toward the site of inflammation. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):7991. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08687-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang L, Yang X, Yin Q, et al. Investigating the optimal size of anticancer nanomedicine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(43):15344–15349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411499111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pernal S, Wu VM, Uskoković V. Hydroxyapatite as a vehicle for the selective effect of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles against human glioblastoma cells. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(45):39283–39302. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b15116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang Z, Li C, Yang S, et al. Magnetic resonance hypointensive signal primarily originates from extracellular iron particles in the long-term tracking of mesenchymal stem cells transplanted in the infarcted myocardium. Int J Nanomedicine. 2015;10:1679–1690. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Silva LHA, Silva SM, Lima ECD, et al. Effects of static magnetic fields on natural or magnetized mesenchymal stromal cells: repercussions for magnetic targeting. Nanomedicine. 2018;14(7):2075–2085. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qiao Y, Gumin J, Maclellan CJ, et al. Magnetic resonance and photo-acoustic imaging of brain tumor mediated by mesenchymal stem cell labeled with multifunctional nanoparticle introduced via carotid artery injection. Nanotechnology. 2018;29(16):165101. doi: 10.1088/1361-6528/aaaf16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosenberg JT, Yuan X, Grant S, Ma T. Tracking mesenchymal stem cells using magnetic resonance imaging. Brain Circ. 2016;2(3):108–113. doi: 10.4103/2394-8108.192521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yun W, Choi J, Ju H, et al. Enhanced homing technique of mesenchymal stem cells using iron oxide nanoparticles by magnetic attraction in olfactory-injured mouse models. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(5):1376. doi: 10.3390/ijms19051376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shen WB, Plachez C, Tsymbalyuk O, et al. Cell-based therapy in TBI: magnetic retention of neural stem cells in vivo. Cell Transplant. 2016;25(6):1085–1099. doi: 10.3727/096368915X689550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khan MR, Dudhia J, David FH, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells do not enhance intra-synovial tendon healing despite engraftment and homing to niches within the synovium. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9(1):169. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0900-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yudintceva NM, Bogolyubova IO, Muraviov AN, et al. Application of the allogenic mesenchymal stem cells in the therapy of the bladder tuberculosis. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2018;12(3):e1580–e1593. doi: 10.1002/term.2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang DM, Hsiao JK, Chen YC, et al. The promotion of human mesenchymal stem cell proliferation by superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2009;30(22):3645–3651. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schäfer R, Kehlbach R, Müller M, et al. Labeling of human mesenchymal stromal cells with superparamagnetic iron oxide leads to a decrease in migration capacity and colony formation ability. Cytotherapy. 2009;11(1):68–78. doi: 10.1080/14653240802666043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhe-Zhen Y, Qing-Hua W, Zhang S-L, Miao J-Y, Zhao B-X, Su L. Two novel amino acid-coated super paramagnetic nanoparticles at low concentrations label and promote the proliferation of mesenchymal stem cells. RSC Advances. 2016;6(12):10159–10161. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beck B, Driessens G, Goossens S, et al. A vascular niche and a VEGF-Nrp1 loop regulate the initiation and stemness of skin tumours. Nature. 2011;478(7369):399–403. doi: 10.1038/nature10525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang C, Wang N, Tan HY, Guo W, Li S, Feng Y. Targeting VEGF/VEGFRs pathway in the antiangiogenic treatment of human cancers by traditional chinese medicine. Integr Cancer Ther. 2018;17(3):582–601. doi: 10.1177/1534735418775828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Qu X, Tang Y, Hua S. Immunological approaches towards cancer and inflammation: a cross talk. Front Immunol. 2018;9:563. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Villalba M, Evans SR, Vidal-Vanaclocha F, Calvo A. Role of TGF-β in metastatic colon cancer: it is finally time for targeted therapy. Cell Tissue Res. 2017;370(1):29–39. doi: 10.1007/s00441-017-2633-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kagiwada H, Yashiki T, Ohshima A, Tadokoro M, Nagaya N, Ohgushi H. Human mesenchymal stem cells as a stable source of VEGF-producing cells. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2008;2(4):184–189. doi: 10.1002/term.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arutyunyan I, Fatkhudinov T, Kananykhina E, et al. Role of VEGF-A in angiogenesis promoted by umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stromal/stem cells: in vitro study. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016;7(1):46. doi: 10.1186/s13287-016-0305-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Öksüz S, Alagöz MŞ, Karagöz H, et al. Comparison of treatments with local mesenchymal stem cells and mesenchymal stem cells with increased vascular endothelial growth factor expression on irradiation injury of expanded skin. Ann Plast Surg. 2015;75(2):219–230. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ponte AL, Marais E, Gallay N, et al. The in vitro migration capacity of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells: comparison of chemokine and growth factor chemotactic activities. Stem Cells. 2007;25(7):1737–1745. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aenlle KK, Curtis KM, Roos BA, Howard GA. Hepatocyte growth factor and p38 promote osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2014;28(5):722–730. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lu Y, Wei L, Zhang X, et al. The Regulation of Mesenchymal stem cell therapy through magnetic resonance imaging agents-based cellular condition and oxygen environment. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2018;14(11):1906–1920. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2018.2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chamberlain G, Smith H, Rainger GE, Middleton J. Mesenchymal stem cells exhibit firm adhesion, crawling, spreading and transmigration across aortic endothelial cells: effects of chemokines and shear. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e25663. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kurtz A. Mesenchymal stem cell delivery routes and fate. Int J Stem Cells. 2008;1(1):1–7. doi: 10.15283/ijsc.2008.1.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Herrera MB, Bussolati B, Bruno S, et al. Exogenous mesenchymal stem cells localize to the kidney by means of CD44 following acute tubular injury. Kidney Int. 2007;72(4):430–441. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]