Abstract

We developed a nontargeted diabetes screening program in a rural Indian Health Service emergency department in Shiprock, New Mexico to measure the proportion of previously undiagnosed diabetes and prediabetes, and to assess glycemic control among patients with known disease. Of 924 patients screened in the emergency department between May and July 2017, 28.8% screened positive for previously undiagnosed diabetes or prediabetes; among patients with known disease, the median hemoglobin A1c was 8.2%. Of the newly identified patients, 54.9% attended follow-up.

American Indians and Alaska Natives have the highest prevalence and mortality rates from diabetes of any ethnic group.1,2 In our institution, screening rates for diabetes are high in the primary care setting, but the emergency department (ED) has been identified as a high-priority and underutilized venue for screening.

INTERVENTION

We implemented a nontargeted diabetes screening protocol into routine clinical care in the ED.

PLACE AND TIME

We conducted this project at Northern Navajo Medical Center, a rural Indian Health Service (IHS) ED located in Shiprock, New Mexico, that sees approximately 35 000 patients a year annually. The ED diabetes screening protocol was in place for 12 weeks between May and July 2017. During the study period, we encouraged physicians to use the bundled laboratory testing that included a hemoglobin A1c test when they ordered any blood tests on patients. Patients did not provide specific consent for A1c screening, but staff notified patients that the ED routinely tests patients for diabetes as part of their clinical care.

PERSON

During the study, all adult patients presenting to the ED who underwent blood testing were eligible for A1c screening. The electronic health record automatically cancelled A1c tests if a patient had undergone A1c testing in the past 75 days. Our analysis specifically focused on unique patients aged 18 years and older.

PURPOSE

In an effort to improve the detection of previously undiagnosed diabetes, we implemented a nontargeted diabetes screening program. As a secondary aim, we assessed the glycemic control of known diabetic patients presenting to our ED.

IMPLEMENTATION

We implemented a diabetes screening program as a recommended, but nonmandated, clinical protocol for all ED patients aged 18 years and older undergoing laboratory testing. We chose a nontargeted screening approach because the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends that clinicians consider screening all American Indian adult patients regardless of age or other risk factors,3 and this has been the practice among primary care providers at our institution for several years. Children and adolescents were offered targeted testing at the physician’s discretion, but we did not include them in the analysis. We modified the electronic health record to have a “Quick Pick List” for ED orders comprising several bundles of commonly ordered laboratory tests, which included an A1c. We analyzed the A1c tests on the D-10 Hemoglobin Testing System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA; coefficient of variation = 1.3%) in the hospital laboratory alongside other ED testing labs. The project staff reviewed the medical records of those with abnormal A1c results to determine whether each patient had a previous diagnosis of diabetes or prediabetes. The diabetes clinic notified patients newly identified with abnormal A1c results by phone call or letter and advised them to see the diabetes clinic or their primary care provider for counseling and confirmatory testing.

EVALUATION

We defined an A1c greater than or equal to 6.5% to be a positive screen for diabetes, and 5.7% to 6.4% to be a positive screen for prediabetes. We defined poorly controlled diabetes to be an A1c greater than or equal to 9.0%. Over the 12-week period, there were 6109 patients who presented to the ED, including 2030 (33.2%) with blood draws; of these, 924 (45.5%; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 43.3%, 47.7%) had an A1c test performed. The characteristics of the study population and the ED population as a whole during the 12-week study period can be seen in Table 1.

TABLE 1—

Characteristics of Patients Screened For Diabetes Compared With General Emergency Department (ED) Population: Northern Navajo Medical Center ED, Shiprock, NM, May–July 2017

| Characteristic | Unique Patients With A1c Screening (n = 924), Mean ±SD, Median (IQR), or No. (%) | All Unique ED Patients During Study Period (n = 6109), Mean ±SD or No. (%) | Absolute Difference (95% CI) |

| Age, y | 50.1 ±18.3 | 48.2 ±18.4 | 1.9 (0.6, 3.2) |

| A1c | 6.0 (5.6–7.6) | … | … |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 444 (48.1) | 2764 (45.2) | 2.9 (–0.6, 6.4) |

| Female | 480 (51.9) | 3345 (54.8) | 2.9 (–0.6, 6.4) |

| Designated primary care provider | |||

| Yes | 484 (52.4) | 2794 (45.7) | 6.7 (3.2, 10.2) |

| No | 440 (47.6) | 3315 (54.3) | 6.7 (3.2, 10.2) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 33.8 (27.0) | 34.5 (26.1) | 0.7 (–1.1, 2.5) |

| Acuity | |||

| High (ESI 1–3) | 703 (76.1) | 1934 (31.7) | 44.4 (41.4, 47.4) |

| Low (ESI 4–5) | 201 (21.8) | 3720 (65.8) | 44.0 (41.1, 46.9) |

| Unknown | 20 (2.2) | 455 (7.4) | 5.2 (4.0, 6.4) |

Note. A1c = hemoglobin A1c; BMI = body mass index (defined as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters); CI = confidence interval; ESI = emergency severity index; IQR = interquartile range.

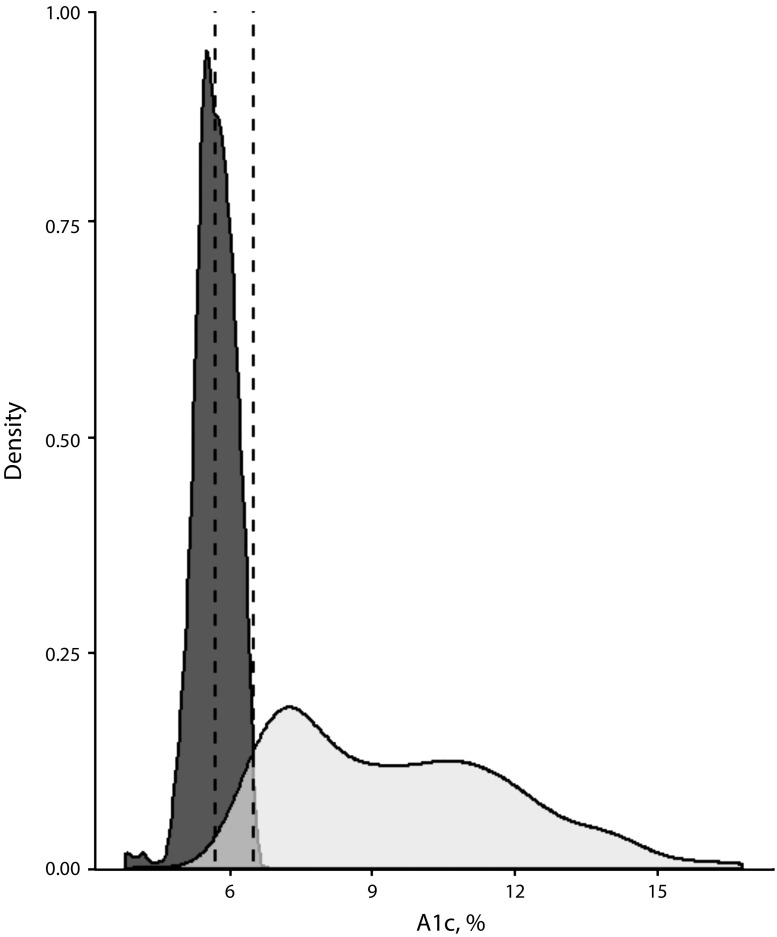

Of the 924 patients tested for diabetes, 637 (68.9%; 95% CI = 65.8%, 71.9%) had an A1c of 5.7% or above. The median A1c for all patients tested was 6.0% (interquartile range [IQR] = 5.6%–7.6%). A total of 242 patients (26.2%; 95% CI = 23.4%, 29.2%) screened positive for previously undiagnosed prediabetes, and 24 (2.6%; 95% CI = 1.7%, 3.8%) screened positive for previously undiagnosed diabetes. Among patients newly identified with diabetes or prediabetes, the median A1c was 6.0% (IQR = 5.8%–6.2%). Of the previously undiagnosed patients, diabetes clinic staff contacted 206 patients (77.4%; 95% CI = 71.9%, 82.3%) regarding their results, and 146 (54.9%; 95% CI = 48.7%, 61.0%) attended a follow-up appointment with the diabetes clinic or their primary care provider. The distribution of A1c values among screened patients stratified by new and prior diagnosis of diabetes or prediabetes is shown in Figure 1. There were 375 patients who had a prior diagnosis of diabetes or prediabetes; this group had a median A1c of 8.2% (IQR = 6.6%–10.7%), and 170 (45.3%; 95% CI = 40.2%, 50.5%) were poorly controlled.

FIGURE 1—

Density Kernel Estimates of the Distributions of A1c Values Among Screened Patients Either With (Light Gray) or Without (Dark Gray) a Preexisting Diagnosis of Diabetes at the Time of A1c Screening: Northern Navajo Medical Center Emergency Department, Shiprock, NM, May–July 2017

Note. Vertical dashed lines mark A1c’s of 5.7% and 6.5%, showing the screening cutoffs for prediabetes and diabetes, respectively.

ADVERSE EFFECTS

We did not identify any significant patient-oriented adverse effects.

SUSTAINABILITY

The main challenge to the sustainability of this program was the high number of patients who screened positive for diabetes and prediabetes. The diabetes clinic was able to accommodate new patients through their walk-in clinics and group classes throughout the duration of the program; because there is a fixed capacity for patients, however, this may not be true indefinitely. As a part of our program, we began training community health workers to follow up with patients and provide counseling on lifestyle modifications in the community. We also found that the majority of previously undiagnosed patients had an A1c in the prediabetes range, and other, similar programs must take this into consideration when allocating resources for diabetes treatment and prevention.

PUBLIC HEALTH SIGNIFICANCE

In this public health program of nontargeted diabetes screening in a Navajo Nation ED, 26.2% of previously undiagnosed patients screened positive for prediabetes and 2.6% screened positive for diabetes. To our knowledge, there is no other literature evaluating a nontargeted, ED-based screening and linkage to care program for both diabetes and prediabetes.

More than 90% of patients newly identified with abnormal A1c results fell into the prediabetes range. This indicates an important opportunity for early interventions, as lifestyle modifications for patients with prediabetes carry a relative risk reduction of 40% to 70% with regard to progression to diabetes.4 Challenges to such lifestyle changes include high rates of food insecurity and poverty in the Navajo Nation, which are among the highest in the United States.5 Given the disparities facing this community, our findings suggest a need to focus on the challenging task of screening and linkage to care for patients identified as high risk for diabetes and prediabetes outside of the primary care setting.

There are several important limitations in our study. We are unable to report random glucose levels alongside A1c results, and our 75-day cutoff for repeat testing may also be overly inclusive. Although patients require a second A1c test to confirm a new diagnosis on a second blood sample, we define our screening A1c levels on the basis of other research in the acute care setting.6 Additionally, fewer than half of eligible patients had an A1c drawn, and we are unable to assess reasons providers may or may not have used the screening bundle. Finally, although the A1c test has advantages over other methods of screening for diabetes that are primarily related to convenience, it does have limitations in patients with certain comorbidities.

The identification of diabetes and prediabetes is a priority for the IHS, and each year there are more than 600 000 visits to IHS and tribal EDs.7 If our program results can be generalized to these other similar EDs, the widespread implementation of nontargeted ED diabetes screening using this electronic health record algorithm stands to identify more than 150 000 adult American Indian/Alaska Native patients annually with diabetes or prediabetes. This significant opportunity for screening should not be overlooked.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are employees of the Indian Health Service.

Note. The views expressed in this article are the authors’ alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Indian Health Service.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None of the authors report any conflicts of interest.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The Navajo Nation institutional review board approved this project.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Diabetes Statistics Report. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2017; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cho P, Geiss LS, Burrows NR, Roberts DL, Bullock AK, Toedt M. Diabetes-related mortality among American Indians and Alaska Natives, 1990–2009. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 3):S496–S503. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siu AL. Screening for abnormal blood glucose and type 2 diabetes mellitus: US Preventative Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(11):861–868. doi: 10.7326/M15-2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bansal N. Prediabetes diagnosis and treatment: a review. World J Diabetes. 2015;6(2):296–303. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v6.i2.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pardilla M, Prasad D, Suratkar S, Gittelsohn J. High levels of household food insecurity on the Navajo Nation. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(1):58–65. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012005630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hng T-M, Hor A, Ravi S et al. Diabetes case finding in the emergency department, using HbA1c: an opportunity to improve diabetes detection, prevention, and care. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2016;4(1):e000191. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2015-000191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernard K, Hasegawa K, Sullivan A, Camargo C. A profile of Indian Health Service emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69(6):705.e4–710.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]