Abstract

Currently, no US jurisdiction or agency routinely or systematically collects information about individuals’ sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) at the time of death. As a result, little is known about causes of death in people having a minority sexual orientation or gender identity. These knowledge gaps have long impeded identification of mortality disparities in sexual and gender minority populations and hampered the development of targeted public health interventions and prevention strategies.

We offer observations about the possibilities and challenges of collecting and reporting accurate postmortem SOGI information on the basis of our past four years of working with death investigators, coroners, and medical examiners. This work was located primarily in New York, New York, and has extended from January 2015 to the present.

Drawing on our experiences, we make recommendations for future efforts to include SOGI among the standard demographic variables used to characterize individuals at death.

We report our recent efforts to encourage the collection of sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) information at the time of death, and we offer observations about a path forward for this critical work. Our involvement in postmortem SOGI identification developed from two premises: first, SOGI is linked to mortality risk in significant but largely undocumented ways; and second, although recent studies of mortality in variously defined samples of sexual and gender minority individuals have contributed important new information,1–7 such research cannot match the timeliness and generalizability of routine, systematic identification of SOGI at death. We describe the results of a project to determine SOGI in decedents, summarize lessons learned, and propose recommendations for next steps to include SOGI as standard demographic variables in US mortality surveillance.

DATA COLLECTION METHOD

In 2014, we convened an expert meeting to address the lack of systematic mortality data among sexual and gender minority people.8 Although they supported routine SOGI identification at the time of death, participating coroners and medical examiners cautioned that few personnel who collect decedents’ personal and demographic data are trained to elicit SOGI information in an accurate and sensitive way. From this discussion, a consensus recommendation emerged for an ongoing working group to develop a protocol to guide death investigators’ collection of postmortem SOGI information. Although mindful that this approach would limit our task to identifying SOGI information in the subset of deaths subject to medicolegal investigation (e.g., suicides, homicides, undetermined deaths), we believed much could be learned from death investigators who were already trained and experienced in collecting other sensitive information about decedents.

Forming the core of the working group, we developed a SOGI data collection method for investigators, working with an advisory group of experienced death investigators, coroners, medical examiners, and personnel from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Consistent with death investigation practices, our method lists open-ended SOGI-related questions to guide investigators’ interviews with informants. Because the goal is to determine SOGI at the time of death, the investigator’s initial questions focus on the last year of the decedent’s life. Additional questions explore the decedent’s gender history to identify transgender or cisgender status. Sexual history questions are also provided to help investigators clarify sexual orientation, especially when information about recent sexual relationships or behavior is not available.

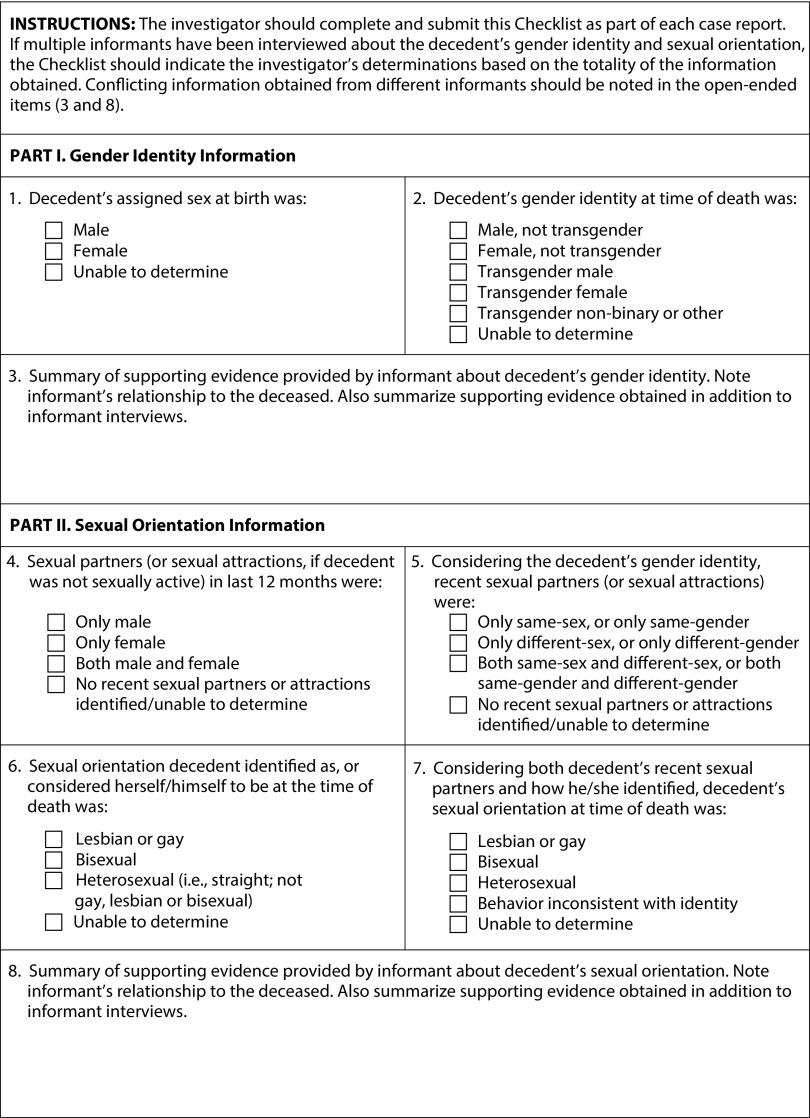

We also developed lists of potential observations at the scene of death and the decedent’s living environment, written documents, and informal statements of witnesses, family members, or friends who may provide important SOGI-related information. Finally, we created a checklist of structured “best practice” SOGI items9–11 for investigators to use in summarizing and reporting the SOGI information gathered from their overall investigatory procedures (Figure 1). Moreover, because some evidence may be directly from the decedent (e.g., suicide note, social media account) and some evidence may be proxy (e.g., informant interview), the checklist asks investigators to indicate the evidence they used to make their determinations of the decedent’s gender identity and sexual orientation.

FIGURE 1—

Investigator Checklist for Reporting Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation

Next, we developed an in-person training program for death investigators, coroners, and medical examiners, which was approved and accredited by the American Board of Medicolegal Death Investigators. The training presents our SOGI data collection protocol, using case examples and role-play exercises to help investigators gain practice and confidence in asking SOGI questions of proxy informants. It also covers procedures for reporting the decedent’s SOGI information to the coroner or medical examiner for inclusion in the death report.

We piloted the training at five sites in three states (i.e., Nevada, Colorado, and New York), involving 114 death investigators and 22 supervisory personnel. In a pretraining assessment, almost 80% of investigators reported having a case in which they thought the decedent might be gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender. None had received training on how to discuss SOGI with informants. Posttraining data showed that more than 90% of participants had a good understanding of SOGI constructs and felt prepared to ask SOGI-related questions of informants. We are planning trainings in more jurisdictions that will include follow-up evaluation to determine the SOGI protocol’s acceptability, use, and results in the field.

In 2018, we used feedback from the pilot trainings and ongoing contacts with training sites to complete a comprehensive manual for investigators.12 We also created a Web site, www.lgbtmortality.com, where the manual and related materials can be accessed.

LESSONS LEARNED

Our experiences make us optimistic about investigators’ willingness and ability to collect SOGI information with appropriate training and support. At the same time, we are more aware of inconsistencies between our approach to postmortem SOGI measurement and that of the CDC’s National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS), which collects and codes state-based records on violent deaths into a comprehensive de-identified database.13 Since 2013, NVDRS has included SOGI codes but, in important respects, these seem more narrowly defined than is ideal, considering the system’s ultimate goal of providing communities with a clearer understanding of violent deaths so they can be prevented.

NVDRS relies essentially on evidence obtained from informants that the decedent self-identified as transgender to determine transgender status, and as heterosexual, gay, lesbian, or bisexual to determine sexual orientation.14 Since 2016, the system has allowed transgender status to be determined by evidence that the decedent was undergoing or had undergone surgery or hormone therapy for gender transition, although there are still no codes for behavioral evidence of sexual orientation. In 2015, NVDRS amended its marital status variable to define all decedents who were in a legal marriage, civil union, or domestic partnership as “married” and added a separate sex-of-spouse or -partner item (same sex or opposite sex). Coders are instructed not to infer sexual orientation from this information, however, and to code sexual orientation as unknown if interview evidence of self-identification is not explicitly found in the coroner or medical examiner report or other death document.

Although self-identification is considered a critical aspect of SOGI identification in surveys and studies of living persons, our work with investigators suggests that many informants lack information about whether a decedent “identified as” or “considered themselves to be” transgender or heterosexual, gay, lesbian, or bisexual. Thus, we find that behavioral questions are an essential part of postmortem SOGI identification. Although informants may not know details about decedents’ sexual behaviors, many are aware of their intimate relationships and the sex of their recent intimate or sexual partners. Capturing this behavioral information accurately will require careful consideration of appropriate time frames. Assessing sexual partners or activity in the recent past (e.g., past 12 months) may improve precision but could inadvertently omit older adults and others who may have been sexually active during their lifetime but not within the defined period.

Along with interview evidence, the coroner or medical examiner’s report may also mention other types of evidence that provide useful SOGI information, for example, suicide notes, journals, legal documents, and social media activity. Developing codes for the behavioral and observational information that is obtained in many death investigations and reported to the state by coroners and medical examiners would likely expand the number of cases in which NVDRS is able to identify decedents’ gender identity and sexual orientation.

As NVDRS acknowledges,14 relying on self-identity alone as a postmortem measure of sexual orientation likely detects only those sexual minority decedents whom family or friends knew to identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual. Using a self-identity item as a sole measure of sexual orientation has been noted as a weakness of some health surveys, because this precludes identification of health risks in sexual minority persons who engage in same-sex sexual behavior or have same-sex sexual attractions but do not openly identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual.15 Not identifying this segment of the sexual minority population in postmortem data is similarly problematic.

In addition, we do not yet know how detailed postmortem gender identity measures need to be to achieve the goal of preventing violent death among transgender people. Recent research pointing to higher lifetime rates of suicide attempts, sexual assault, and other acts of violence among nonbinary transgender persons compared with transgender men or women16 suggests that replacing the general “transgender” checkbox used by NVDRS with gender identity categories would help identify subgroups at the greatest risk for violent death.

Finally, with respect to our own approach, we note that our checklist needs further development and testing to make it more useful for investigators, coroners, and medical examiners to report SOGI information. Our experience suggests that the SOGI-related evidence investigators collect in the field does not always align with the best practices items we incorporated into our reporting form. Although these items have performed well in self-report surveys, a checklist of the decedent’s observable behaviors as reported by informants, as well as specific observational and documentary evidence, is likely to be more useful in death investigations. In the next phase of our work, reports from a larger number of investigators and cases will be examined to identify the types of evidence on which investigators base their determinations of SOGI in decedents of different ages and other characteristics. We anticipate that this information will be helpful in guiding the development of an improved reporting form.

AMENDING THE DEATH CERTIFICATE

Since 2014, California,17 New Jersey,18 and Rhode Island19 passed legislation requiring the death certificate to record the decedent’s sex as reported by the primary informant or as indicated in legal documents or medical records. Although this amendment advances respect for transgender people after death, it is unclear whether these states record sex in a way that allows decedents to be identified as transgender.

Advocates in some states have suggested adding a sex-of-spouse item to the death certificate to assist in identifying sexual minority individuals who were married to a same-sex spouse at the time of death. Currently, the death certificate lists the name of a married decedent’s surviving spouse, but because names are not always indicative of sex, identifying the spouse’s sex would facilitate detection of same-sex married decedents. This could lead to important new information about mortality in this subset of sexual minority persons.

A 2017 national survey suggested that about 10% of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT)-identified adults in the United States are currently married to a same-sex spouse.20 By contrast, 13% of LGBT adults (primarily bisexual) are married to an opposite-sex spouse, 56% have never been married, and 21% are formerly but not currently married. Although information about mortality in same-sex married decedents may not be applicable to all sexual minority decedents, a sex-of-spouse item may help demonstrate the relevance of sexual orientation in mortality surveillance. This, in turn, could provide an impetus for adding other items to the death certificate to identify sexual orientation independent of marital status.

Current SOGI-related amendments to the death certificate affect practices only in individual states, and no similar efforts are under way to change the US Standard Certificate of Death. That document, the single most basic source of information about national mortality, has been revised only 10 times since its inception in 1900, most recently in 2003.21

GOING FORWARD

Four years after our 2014 meeting, it remains apparent that the routine, systematic collection of SOGI information at death is necessary to identify the causes and patterns of mortality in sexual and gender minority people. We cannot reduce or prevent what we cannot see, and our continued blindness to SOGI-related mortality risks ensures only that prevention will continue to be stalled and that lives will continue to be unnecessarily lost. Knowing that we must identify SOGI in decedents is far simpler, however, than knowing how best to do that. On the basis of our experiences, we offer the following recommendations for future efforts:

A coordinated national conversation is needed about the best ways to measure SOGI constructs in a death investigation, with the aim of melding the strengths of the investigator’s open-ended approach with the data structure required by NVDRS. Standardizing the way SOGI data are collected by the investigator, reported to the state by the coroner or medical examiner, and coded by NVDRS will enhance the goal of understanding risk of violent death in the widest possible number of sexual and gender minority people, which can then inform prevention efforts.

Systematic training of all personnel involved in death documentation is essential to achieve accurate collection of SOGI information. In addition to death investigation personnel, funeral directors, who are charged with completing the demographic and personal data section of the death certificate in consultation with the decedent’s primary informant, will require training to ensure compliance with any new state mandates for SOGI data collection. Innovative ways of financing and delivering such training will need to be found, possibly involving relevant state and national professional associations and nonprofit organizations, as well as state and federal agencies.

Adding carefully considered SOGI items to state death certificates provides valuable opportunities to evaluate their feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness, which may eventually lead to universal SOGI identification through amendments to the US Standard Certificate of Death. In particular, systematic evaluation should seek evidence that addresses the three standards for proposed new items to be added to the federal death certificate. Is the item needed for legal, research, statistical, or public health programs? Is it collectible with reasonable completeness and accuracy? And is the vital statistics system the best source for this information?21

Government initiatives such as the Federal Interagency Working Group on Measuring Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity should expand their current focus on surveys of living persons to include postmortem collection of SOGI information.

We are gratified that our work has helped build interest in postmortem SOGI identification, and we look forward to engaging with others as we continue to pursue this important effort.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded in part by the Johnson Family Foundation and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. It was partly supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (Health Services Research and Development Career Development Award CDA-14-408 to J. R. B.).

Note. The opinions expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funders, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the US government.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

See also Mays and Cochran, p. 192.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cochran SD, Mays VM. Sexual orientation and mortality among US men aged 17 to 59 years: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(6):1133–1138. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cochran SD, Mays VM. Mortality risks among persons reporting same-sex sexual partners: evidence from the 2008 General Social Survey—national death index data set. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):358–364. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cochran SD, Björkenstam C, Mays VM. Sexual orientation and all-cause mortality among US adults aged 18 to 59 Years, 2001–2011. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(5):918–920. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blosnich JR, Brown GR, Wojcio S, Jones KT, Bossarte RM. Mortality among veterans with transgender-related diagnoses in the Veterans Health Administration, FY2000–2009. LGBT Health. 2014;1(4):269–276. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehavot K, Rillamas-Sun E, Weitlauf J et al. Mortality in postmenopausal women by sexual orientation and veteran status. Gerontologist. 2016;56(suppl 1):S150–S162. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hottes TS, Ferlatte O, Gesink D. Suicide and HIV as leading causes of death among gay and bisexual men: a comparison of estimated mortality and published research. Crit Public Health. 2014;25(5):513–526. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis JM, Suleta K, Corsi KF, Booth RE. A hazard analysis of risk factors of mortality in individuals who inject drugs in Denver CO. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(4):1044–1053. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1660-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haas AP, Lane A. Collecting sexual orientation and gender identity data in suicide and other violent deaths: a step toward identifying and addressing LGBT mortality disparities. LGBT Health. 2015;2(1):84–87. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Badgett MV. Best Practices for Asking Questions About Sexual Orientation on Surveys. Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herman JL. Best Practices for Asking Questions to Identify Transgender and Other Gender Minority Respondents on Population-Based Surveys. Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fenway Institute. Center for American Progress. Asking patients questions about sexual orientation and gender identity in clinical settings: a study of four health centers. Available at: http://thefenwayinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/COM228_SOGI_CHARN_WhiteArticle.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2018.

- 12.Haas AP, Lane AD, Blosnich JR, Butcher BA, Mortali MG. Sexual orientation and gender identity: a guide for the investigator. Available at: https://www.lgbtmortality.com. Accessed August 21, 2018.

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance for violent deaths—National Violent Death Reporting System, 18 states, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67(2):1–36. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6702a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) Coding Manual Revised. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzales G, Henning-Smith C. Health disparities by sexual orientation: results and implications from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. J Community Health. 2017;42(6):1163–1172. doi: 10.1007/s10900-017-0366-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atkins A, Ammiano A, Leno S. An act to amend section 102875 of the Health and Safety Code, relating to certificates of death. 2014. Available at: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201320140AB1577. Accessed March 3, 2018.

- 18.State of New Jersey. Senate No. 493. An act concerning information included on death certificates and amending R.S.26:6–7. Available at: http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2018/Bills/S0500/493_I1.HTM. Accessed March 10, 2018.

- 19.State of Rhode Island. An act relating to health and safety—vital records. 2018. Available at: http://webserver.rilin.state.ri.us/BillText18/HouseText18/H7765.pdf. Accessed July 23, 2018.

- 20.Jones JM. In U.S., 10.2% of LGBT adults now married to same-sex spouses. 2017. Available at: https://news.gallup.com/poll/212702/lgbt-adults-married-sex-spouse.aspx. Accessed July 23, 2018.

- 21.National Center for Health Statistics, Division of Vital Statistics. Report of the Panel to Evaluate the U.S. Standard Certificates. Hyattsville, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]