Abstract

Objectives. To describe time trends in the availability of healthier children’s menu items in the top selling quick service restaurant (QSR) chains.

Methods. We used Technomic Inc.’s MenuMonitor to construct a data set of side and beverage items available on children’s menus from 2004 to 2015 at 20 QSR chains in the United States. We evaluated the significance of time trends in the average availability of healthier fruit and nonfried vegetable sides and nonsugary beverages offered as options and by default in children’s meal bundles.

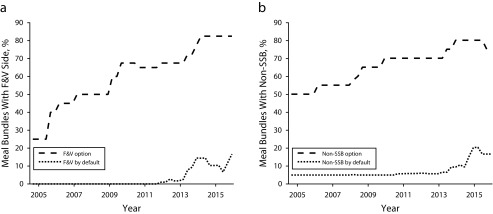

Results. Healthier sides and beverages offered as options increased by 57.5 and 25.0 percentage points, respectively, from 2004 to 2015 but leveled off starting in 2013. Healthier items bundled by default also increased during this time frame, with most adoption occurring after 2010. However, these items remain relatively uncommon, with less than 20% of meal bundles including healthier items by default. All tests evaluating time trends in the availability of healthier items in meal bundles were significant at P < .001.

Conclusions. The QSRs evaluated made improvements in the quality of sides and beverages offered on children’s menus from 2004 to 2015. Additional efforts are needed to increase the percentage of healthier options offered by default.

Increasing the availability of healthier side and beverage options on restaurant menus can encourage the consumption of food groups currently lacking in the diets of American children such as fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy.1–3 Children’s restaurant meals that include fruit and nonfried vegetable sides (hereafter F&V sides) and nonsugary beverages also tend to be lower in calories than meals without these options.2–4 Given that children consume an average of 126 to 161 excess calories on days when they eat out,5 increased availability of healthier sides and beverages could help counteract some of the negative effects of restaurant meals on diets.

Making healthier items the default option could have an even greater impact. Individuals are more likely to select options that are offered by default in a variety of domains (e.g., during end-of-life care and in restaurants).2,3,6 In a study of a large quick service restaurant (QSR) chain, orders of apple slices increased by 87.7 percentage points when they were included in the children’s meal bundle relative to when they were offered as an option.3 Similar increases in orders of healthier sides and beverages have been found in full-service restaurants.2 Given the importance of healthier options being available (ideally by default), we evaluated time trends in the availability of healthier F&V sides and nonsugary beverages on children’s menus, both by default and as options, from 2004 to 2015 in a sample of the top selling QSR chains in the United States.

METHODS

In 2016, we used data from Technomic’s MenuMonitor (Technomic Inc, Chicago, IL) to construct a historical children’s menu analysis file in Microsoft Excel. We abstracted and coded children’s menu item data from the third quarter of 2004 (July–September; the first available time point) to the fourth quarter of 2015 (October–December) for 20 of the 50 leading QSRs based on 2014 system-wide sales.7 We also evaluated whether these data were consistent with archived versions of online menus (see the Appendix, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Healthier sides, defined as F&V sides, were coded by 2 trained researchers according to procedures adapted from Anzman-Frasca et al.4 (see the Appendix). Healthier, nonsugary beverages were defined as beverages that were not a sugar-sweetened carbonated, fruit-flavored, coffee, or other sugar-sweetened drink, including flavored milk.8 We classified 100% fruit juices as nonsugary beverages as a result of their categorization in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.1 Because they were not consistently listed separately in the database or archived menus, all fountain drinks (including diet beverages) were collapsed into a single beverage item and coded as sugary beverages. The top sides and beverages offered are shown in Table A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Also, on the basis of meal descriptions (e.g., junior burger with apple slices and 100% orange juice), we determined whether meals included healthier sides or beverages as options or whether these items were bundled with meals by default.

We calculated summary statistics to evaluate the average relative availability of F&V sides and nonsugary beverages offered by default and as options in children’s meal bundles across QSRs at each time point. For 2 chains that merged before 2004 (Checkers/Rally’s and Hardees/Carl’s Jr.; Table B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org), we averaged counts of items before conducting any analyses. Simple linear regression models were used to evaluate whether the average percentage of meal bundles that included F&V sides or nonsugary beverages by default or as options increased significantly over time. Because all trend lines were nonlinear, we evaluated various functional forms, and we report P values for the best-fitting models based on adjusted R2 values (Table C, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). All analyses were conducted in Stata version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

The 20 QSRs examined increased the average percentage of meal bundles that included healthier sides and beverages by default (by 16.7 and 11.7 percentage points, respectively; Figure 1). However, healthy defaults were available in only 30% of the restaurant chains evaluated and less than 20% of all meal bundles, with the majority of initial adoptions between 2010 and 2015.

FIGURE 1—

Trends in the Availability of Healthier (a) Sides and (b) Beverages Offered as Options and by Default in Children’s Meal Bundles: US Quick Service Restaurants, 2004 to 2015

Note. FFV = fruit and nonfried vegetable side; SSB = sugar-sweetened beverage.

There were 57.5 and 25.0 percentage point increases in meal bundles that included at least 1 F&V side or nonsugary beverage option from 2004 to 2015, respectively, but increases in the availability of healthier options started to plateau in 2013 (Figure 1). The majority of QSRs (70%) adopted healthier sides and beverages as an option between 2005 and 2010, with large variations in relative availability by chain (Table B).

All tests for overall time trends in the availability of F&V sides and nonsugary beverages offered as options and by default in meal bundles were significant (P < .001; Table C).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated 11-year trends in the availability of children’s meal bundles with healthier F&V sides and nonsugary beverages. We found that the availability of healthier side and beverage options in children’s meal bundles increased significantly, by 57.5 and 25.0 percentage points, respectively. These findings are consistent with other studies showing improvements in the nutrition content and quality of children’s menu items over shorter time frames.9 Yet, these healthier items were not often offered by default, which can increase the likelihood of selection.2,3 Only 30% of chains and less than 20% of meal bundles included healthier sides or beverages by default. Given that sides and beverages contribute substantially to the total calories and quality of restaurant meals,3,4 increases in the availability of healthier side and beverage options have important implications for the approximately 25.3 million US children who eat out on a given day.10 Additional efforts are needed to encourage restaurants to take the stronger step of offering these items by default.

Several recent policy efforts may continue to drive the restaurant industry to offer healthier items by default. In Baltimore, for example, policies have been proposed to require healthier beverages to be offered by default in children’s meals; such policies could encourage chains to adopt such changes nationwide.11 Other policy efforts, including calorie labeling, may also encourage restaurants to change the overall composition of meal bundles so that they include lower calorie side and beverage items such as fruits, vegetables, and water.9 Similarly, participation in voluntary initiatives such as the Kids LiveWell program,12 which requires that at least 1 children’s meal on the menu include foods such as fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy, can increase the availability of these types of items on children’s menus. Future studies should evaluate whether these programs and policies affect menu offerings.

The strengths of this study include the use of longitudinal children’s menu data and our ability to evaluate meal bundles as they were listed on menu boards, unlike in previously published research (Technomic staff, personal communication, June 2015).4,9 Limitations include the observational study design and inconsistencies in how fountain drinks were listed in the database and on archived menus, which affected our ability to evaluate the relative availability of sugary versus diet fountain beverages. Furthermore, we acknowledge that in identifying healthier sides according to F&V food groups, we have omitted other side items that are healthy (e.g., brown rice).

PUBLIC HEALTH IMPLICATIONS

As families acquire more food away from home, it is important to consider what is available on restaurant menus. Although improvements in the availability of healthier sides and beverages on children’s menus have been made, efforts to continue to improve what is available to children in restaurants are needed, especially in terms of default side and beverage items.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the staff at Technomic Inc. for their support in constructing the database, Danielle Krobath for her assistance with quality review procedures, and the JPB Foundation and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation for the funding to make this work possible.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No protocol approval was needed for this study because no human participants were involved.

REFERENCES

- 1.2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture and US Department of Health and Human Services; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anzman-Frasca S, Mueller MP, Sliwa S et al. Changes in children’s meal orders following healthy menu modifications at a regional US restaurant chain. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23(5):1055–1062. doi: 10.1002/oby.21061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wansink B, Hanks AS. Calorie reductions and within-meal calorie compensation in children’s meal combos. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;22(3):630–632. doi: 10.1002/oby.20668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anzman-Frasca S, Dawes F, Sliwa S et al. Healthier side dishes at restaurants: an analysis of children’s perspectives, menu content, and energy impacts. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11(1):81. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-11-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powell LM, Nguyen BT. Fast-food and full-service restaurant consumption among children and adolescents: effect on energy, beverage, and nutrient intake. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(1):14–20. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halpern SD, Loewenstein G, Volpp KG et al. Default options in advance directives influence how patients set goals for end-of-life care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(2):408–417. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The QSR Top 50. QSR Magazine. Available at: https://www.qsrmagazine.com/reports/qsr50-2014-top-50-chart. Accessed December, 2015.

- 8.Zheng M, Rangan A, Allman-Farinelli M, Rohde JF, Olsen NJ, Heitmann BL. Replacing sugary drinks with milk is inversely associated with weight gain among young obesity-predisposed children. Br J Nutr. 2015;114(9):1448–1455. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515002974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bleich SN, Wolfson JA, Jarlenski MP. Calorie changes in chain restaurant menu items: implications for obesity and evaluations of menu labeling. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(1):70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vikraman S, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Caloric intake from fast food among children and adolescents in the United States, 2011–2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2015;213:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rock M, Meyers P. Baltimore City healthy kids meals bill becomes law. Available at: https://health.baltimorecity.gov/news/press-releases/2018-07-18-baltimore-city-healthy-kids-meals-bill-becomes-law. Accessed December 6, 2018.

- 12.National Restaurant Association. Kids LiveWell program. Available at: http://www.restaurant.org/Industry-Impact/Food-Healthy-Living/Kids-LiveWell. Accessed December 6, 2018.