Abstract

In March 2017, Rhode Island released treatment standards for care of adult patients with opioid use disorder. These standards prescribe three levels of hospital and emergency department treatment and prevention of opioid use disorder and opioid overdose and mechanisms for referral to treatment and epidemiological surveillance. By June 2018, all Rhode Island licensed acute care facilities had implemented policies meeting the standards’ requirements. This policy has standardized care for opioid use disorder, enhanced opioid overdose surveillance and response, and expanded linkage to peer recovery support, naloxone, and medication for opioid use disorder.

In 2016, the Rhode Island state legislature enacted legislation requiring “comprehensive discharge planning for patients treated for substance use disorders, opioid overdoses, and chronic addictions.”1 In March 2017, the Rhode Island Department of Health (RIDOH) and Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals (BHDDH) released treatment standards—Levels of Care for Rhode Island Emergency Departments and Hospitals for Treating Overdose and Opioid Use Disorder (hereafter Levels of Care; http://health.ri.gov/publications/guides/LevelsOfCareForTreatingOverdoseAndOpioidUseDisorder.pdf)—for emergency and inpatient care of adult patients with opioid use disorder (OUD).2

INTERVENTION

This policy outlines three care levels (see the appendix, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Level 3 facilities provide patient education on safe opioid storage and disposal, substance use disorder screening, linkage to treatment upon discharge, peer recovery consultation, fentanyl testing, naloxone distribution, and 48-hour opioid overdose reporting. Level 2 facilities meet level 3 requirements and have trained staff who conduct comprehensive substance use assessments and initiate medication for OUD. Level 1 facilities meet the requirements for levels 2 and 3, can maintain individuals on OUD medication, and provide additional services for comprehensive treatment.

PLACE AND TIME

Rhode Island has one of the highest rates of opioid overdose deaths nationwide,3 with 30.2 deaths per 100 000 residents in 2017.4 RIDOH and BHDDH released the Levels of Care standards as part of a coordinated statewide strategy designed to reduce opioid overdose deaths and improve treatment engagement.1 Full policy implementation and certification occurred from May 2017 to June 2018. RIDOH provided hospitals with technical assistance to optimize policy adoption and fidelity from July 2017 to June 2018.

PERSON

The 12 licensed acute care facilities in Rhode Island serve 1.06 million people, and there are 100 to 170 opioid overdose visits each month. The federally operated Veterans Affairs hospital and Butler Hospital, a psychiatric facility with limited medical stabilization capabilities, were not mandated to achieve Levels of Care certification. RIDOH has required the remaining 10 facilities to provide at minimum level 3 services.

PURPOSE

The Levels of Care policy aims to improve and standardize care provided to adult patients with OUD, prevent opioid overdose deaths, increase linkage to treatment, and improve the timeliness of overdose surveillance.

IMPLEMENTATION

Several Levels of Care components were implemented prior to March 2017. In April 2014, RIDOH emergency regulations mandated 48-hour opioid overdose reporting5 via an online data collection tool that has been iteratively revised to improve data quality.6 In 2014, three hospitals began providing take-home naloxone,7 and the Anchor Recovery Community Center launched the AnchorED program, a peer recovery support and navigation service targeting opioid overdose patients visiting an emergency department (ED).8

In July 2017, RIDOH began providing hospitals with technical assistance in their implementation efforts. This assistance included site visits and semistructured interviews with administrators from departments of emergency medicine, psychiatry, nursing, social work, pharmacy, and hospital to assess baseline services and identify implementation barriers and facilitators. After the initial site visits, support in answering questions, reviewing protocols, and troubleshooting implementation barriers was available via telephone and e-mail.

After facilities had applied for Levels of Care certification, RIDOH and BHDDH representatives conducted site visits to evaluate whether policies and procedures met the certification standards. Prior to implementation, many hospitals consulted peer recovery coaches, reported overdoses to RIDOH, or provided take-home naloxone. Hospitals were certified throughout the implementation year and did not receive incentives to achieve higher levels of certification. At the completion of the implementation, four hospitals were certified as level 3 and six as level 1.

EVALUATION

Evaluation to date has included assessment of implementation facilitators and barriers and use of hospital 48-hour overdose reporting data for epidemiological surveillance.

Implementation

Implementation facilitators and barriers were assessed through semistructured interviews conducted according to the consolidated framework for implementation research.9 Commonly referenced and observed facilitators and barriers pertained to Levels of Care policies, in- and out-of-hospital environments, individual stakeholder characteristics, and the implementation process (Table 1). Support of the Levels of Care on the part of ED leadership facilitated implementation.

TABLE 1—

Facilitators of and Barriers to Implementation of the Levels of Care Standards and Attainment of Higher Certification Levels: Rhode Island, 2017–2018

| Implementation Area | Facilitator | Barrier |

| Intervention characteristics | Belief in effectiveness of Levels of Care policies | Intervention externally developed |

| Policy adaptability to local context | Skepticism of effectiveness of Levels of Care policies | |

| Adaptable requirements unclear | ||

| Out-of-hospital variables | Public pressure to address opioid overdose crisis | Unsuccessful stakeholder engagement |

| Hospital-to-hospital competition, public relations pressure to be seen as “taking action” | Limited outpatient availability of medication for OUD with respect to both individual providers and clinic hours of operation | |

| Strong community–hospital partnerships | Lack of or weak community–hospital partnerships | |

| RIDOH regulatory requirements | ||

| Provision of state-sponsored training related to OUD medication | ||

| In-hospital variables | Interdepartmental collaboration: pharmacy, social work, psychiatry, emergency medicine | Lack of interdepartmental collaboration and coordination |

| Support and engagement of hospital leadership | Lack of organizational prioritization | |

| Institutional purchasing of naloxone, fentanyl testing | Unengaged/remote hospital leadership | |

| Electronic medical record order sets, provider reminders, custom forms, report generation | Cost of naloxone and fentanyl testing | |

| Dedicated staff for overdose reporting | Time and labor burden of overdose reporting | |

| Local expertise in addiction medicine, OUD medication | Unavailability of local addiction medicine specialists and buprenorphine waivered providers | |

| Individual stakeholder characteristics | Provider knowledge about OUD and comfort with initiation of OUD medication RIDOH technical assistance |

Stigma toward patients with OUD and OUD medication |

| Provider training and self-efficacy in initiating OUD medication | ||

| Implementation process | Local champions in emergency medicine, social work, psychiatry RIDOH technical assistance |

Absence of local champion |

| Lack of staff or training to carry out policies |

Note. OUD = opioid use disorder; RIDOH = Rhode Island Department of Health.

Conversely, skepticism about externally developed care standards impeded policy adoption. Public pressure to address the opioid crisis, community–hospital partnerships, and RIDOH regulatory requirements supported expedient implementation. Factors within each site that facilitated implementation included interdepartmental collaboration, participation of hospital leaders, dedicated overdose reporting staff, and use of electronic medical record order sets, provider reminders, and report generation. The presence of a physician, nurse, social worker, or pharmacist champion effectively addressed implementation challenges at multiple sites.

Commonly cited institutional barriers to level 3 implementation included naloxone cost, outpatient treatment availability, and availability of personnel for discharge planning and 48-hour reporting. Commonly referenced barriers to level 1 and level 2 implementation included provider knowledge and training gaps about OUD medication and limited availability of community OUD treatment providers or clinic hours. Sites with access to a comprehensive addiction specialist (level 2) also had linkages to outpatient addiction treatment centers meeting level 1 criteria, resulting in more level 1 than level 2 applications. The most commonly cited barrier to service provision was pervasive stigma among providers and staff toward patients with OUD and about OUD medication, including reluctance to dedicate additional resources to patients and moralizing OUD as a personal flaw rather than a complex biopsychosocial disease.

Epidemiological Surveillance

RIDOH uses the 48-hour reporting system for weekly monitoring of opioid overdose frequency, identification of city and county overdose hot spots, and assessment of service provision. Data summaries are publicly available on the state drug overdose data dashboard, PreventOverdoseRI.org.10 The 48-hour reporting in place has enabled service evaluations on a weekly basis. RIDOH responds to declines in service provision by directly engaging hospitals and EDs to identify and remove provision barriers.

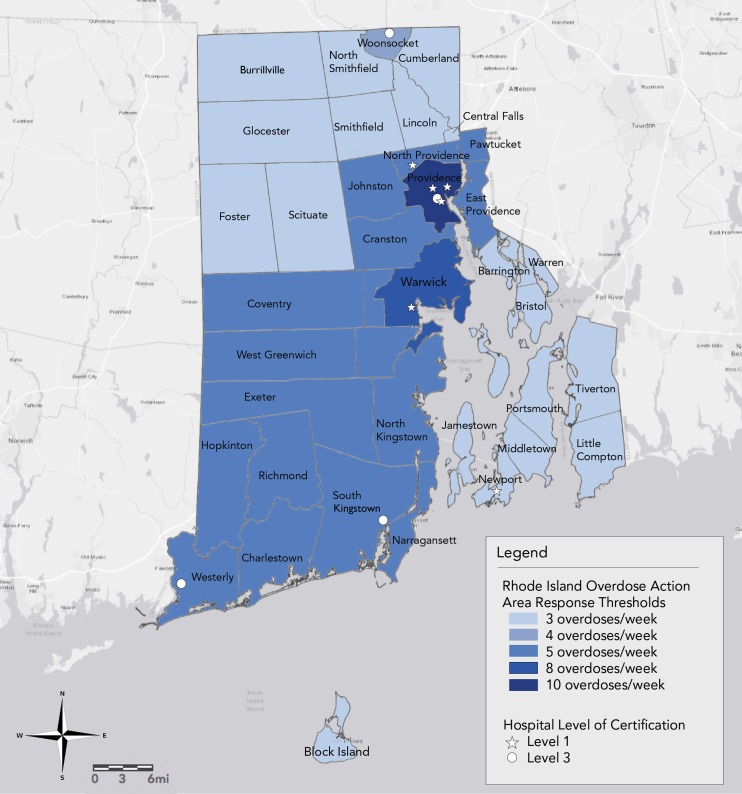

Using 48-hour reporting data for overdose surveillance, RIDOH divided the state into 11 overdose action areas based on average overdoses per week in 2015 (Figure 1). Weekly overdose counts exceeding a set threshold of two standard deviations above the mean trigger an overdose action area response. This response entails releasing a public health advisory to local key stakeholders, including municipal leaders, OUD treatment providers, ED providers, emergency medical services, and municipal, town, and state law enforcement and overdose prevention organizations, as well as peer support programs and people who use drugs and their family members. If an area has three or more overdose action area responses in sixweeks, RIDOH calls a community overdose engagement meeting during which these same stakeholders ascertain causes of increases in overdoses, identify treatment and coordination gaps, and develop strategies to increase the reach of overdose prevention and treatment engagement services.

FIGURE 1—

Rhode Island Overdose Action Areas and Hospital Certification Levels, 2017–2018

ADVERSE EFFECTS

Hospital-related costs included naloxone purchasing, workforce time and effort, provider and staff training on new policy protocols and procedures, and electronic medical record modifications.

SUSTAINABILITY

The Levels of Care standards are jointly supported by RIDOH and BHDDH. Hospitals are responsible for policy implementation and maintenance. Primary obstacles to sustainability are increasing naloxone demand and increasing costs, which have led to several hospital inpatient services opting to prescribe rather than distribute naloxone.

PUBLIC HEALTH SIGNIFICANCE

The Levels of Care create a minimum treatment standard for patients with OUD and those treated after an opioid overdose in Rhode Island EDs and hospitals. The 48-hour reporting system has enabled identification of overdose hot spots and changes or gaps in service use, allowing for rapid hospital engagement to identify and rectify lapses in addiction service provision.

Next steps for policy expansion include incentivizing facilities to advance from level 3 to level 1 and providing additional technical assistance for ED initiation of medication for OUD. Future evaluations will entail assessments of implementation fidelity, comparisons of high- and low-performing sites, and, more broadly, evaluations of the impact of the Levels of Care standards on recurrent overdoses, overdose mortality, and treatment engagement for sustained recovery.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Elizabeth A. Samuels was supported by the National Clinician Scholars Program and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Note. The authors assume full responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the ideas presented, which do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs; the Rhode Island Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals; the Rhode Island Department of Health; or any other supporting intuitions.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No conflicts of interest.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No protocol approval was needed for this study because no human participants were involved.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rhode Island General Assembly. An Act Relating to Health and Safety—Comprehensive Discharge Planning. Available at: http://webserver.rilin.state.ri.us/BillText16/senateText16/S2546.htm. Accessed November 10, 2018.

- 2.Rhode Island Department of Health. Levels of care for Rhode Island emergency departments and hospitals for treating overdose and opioid use disorder. Available at: http://health.ri.gov/publications/guides/LevelsOfCareForTreatingOverdoseAndOpioidUseDisorder.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2018.

- 3.Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(50–51):1445–1452. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rhode Island Department of Health. Drug overdose deaths. Available at: http://www.health.ri.gov/data/drugoverdoses. Accessed November 12, 2018.

- 5.Rhode Island Department of Health. Rules and regulations pertaining to opioid overdose prevention and reporting. Available at: http://www.noperi.org/files/misc/HEALTH%20emergency%20regs%20reporting.pdf. Accessed November 12, 2018.

- 6.McCormick M, Koziol J, Sanchez K. Development and use of a new opioid overdose surveillance system, 2016. R I Med J. 2017;100(4):37–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samuels EA. Emergency department naloxone distribution: a Rhode Island Department of Health, recovery community, and emergency department partnership to reduce opioid overdose deaths. R I Med J. 2014;97(10):38–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Addiction Policy Forum. AnchorED Rhode Island. Available at: https://www.addictionpolicy.org/blog/anchored-rhode-island. Accessed November 12, 2018.

- 9.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marshall BDL, Yedinak JL, Goyer J, Green TC, Koziol JA, Alexander-Scott N. Development of a statewide, publicly accessible drug overdose surveillance and information system. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(11):1760–1763. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]