Abstract

Renal function assessment is of the utmost importance in predicting drug clearance and in ensuring safe and effective drug therapy in neonates. The challenges to making this prediction relate not only to the extreme vulnerability and rapid maturation of this pediatric subgroup but also to the choice of renal biomarker, covariates, and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) estimating formula. In order to avoid burdensome administration of exogenous markers and/or urine collection in vulnerable pediatric patients, estimation of GFR utilizing endogenous markers has become a useful tool in clinical practice. Several estimation methods have been developed over recent decades, exploiting various endogenous biomarkers (serum creatinine, cystatin C, blood urea nitrogen) and anthropometric measures (body length/height, weight, muscle mass). This article reviews pediatric GFR estimation methods with a focus on their suitability for use in the neonatal population.

Keywords: creatinine, cystatin C, glomerular filtration rate, neonates, pediatric, renal function, review

Introduction

Renal function assessment in neonates is of the utmost importance in predicting drug dosing, ensuring safe drug therapy, and detecting acute kidney injuries early. However, the extreme vulnerability, unique body composition, and rapid growth and maturation of young infants make this a rather challenging task. Premature infants present additional difficulties in assessing kidney function because nephrogenesis, which normally would continue until the 36th week of gestation in utero, is interrupted at preterm birth.1

Birth is associated with significant hemodynamic and renal function adaptations. The most striking postnatal transition is represented by a rapid increase in renal blood flow and a consequential rise in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) over the first 2 weeks of life.2 The GFR approaches adult levels between 1 and 2 years of age and matures more rapidly than tubular functions, resulting in a glomerulotubular imbalance specific to neonates.3

Premature infants are born in the second or third trimester, when nephrogenesis is most active. Recent study4 findings are suggestive of postnatal renal maturation following preterm birth; however, this growth appears to be stunted, as the newly formed glomeruli are far fewer and morphologically abnormal. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that a full complement of nephrons may never be achieved, compared to term newborn controls. Glomerulogenesis was also markedly decreased in preterm infants compared to term controls and correlated significantly with gestational age.5 Moreover, neonates born small for gestational age (SGA) were reported6 to have a 16.2% reduction in drug clearance, which was observed from birth to 4 weeks of age. Extrauterine growth restriction, sepsis, asphyxia, and drug therapy may have additional impact on GFR and thereby on the renal clearance of drugs.7

Renal Biomarkers for Neonatal Use

Serum Creatinine. Serum creatinine (SCr) is an established renal biomarker, and it is also a reasonable estimator of GFR in infants. It was reported8 to be inversely correlated with body weight and gestational age (GA) in young infants. In addition, SCr has also been validated9,10 with the inulin clearance method in neonates. Serum creatinine crosses the placenta, which results in high levels at birth and for the first 72 hours of life as a result of the infant's difficulty in eliminating excess SCr transferred from its mother in utero. Serum creatinine values show a steady decline and reach stable levels by 1 to 2 weeks of age in term neonates. Preterm infants show higher SCr values at birth compared to term infants coupled with a slower decline over the first 3 to 4 weeks of life. This observation is most likely due to tubular secretion and creatinine reabsorption by immature tubular cells.11 Serum creatinine is dependent on body mass, and as such, its use as a neonatal renal biomarker can result in high interindividual variability among neonates because of body weight.12

There are 2 assay methods for clinical laboratory use to measure SCr: the Jaffe and enzymatic methods. The Jaffe method is known to falsely elevate SCr as a result of non-specific protein interference; therefore, it is no longer recommended for use. Bilirubin is physiologically elevated in the newborn period; therefore, protein interference caused by the Jaffe method has even more significant implications early in life. The enzymatic method relying on isotope dilution mass spectrometry is the current recommended international standardized method because of its high sensitivity and the smaller amount of background interference associated with it.13 Given the extreme low SCr values in young infants, test sensitivity has major implications on measurements.

Cystatin C. This novel renal biomarker has been proposed for neonatal use as a result of its limited ability to cross the placenta, its analytical sensitivity, and its shorter half-life in serum. Cystatin C (CysC) is not dependent on body mass or sex. However, respiratory distress, asphyxia, concomitant use of aminoglycosides, and sepsis may affect its values.14 Furthermore, CysC has not been extensively validated with inulin in neonates, and its preferred measurement assay (nephelometric test) needs improved standardization.15

Beta Trace Protein. Prostaglandin D2 synthase, or beta trace protein, is another innovative renal bio-marker. Beta trace protein is primarily expressed in the choroid plexus, and it is independent of height, sex, age, muscle mass, and maternal renal function.16 Beta trace protein is also freely filtered by the glomeruli; however, only minimal pediatric data are available at present.

Attempts have also been made to correlate GFR with total kidney volume as a surrogate of nephron mass in neonates. Total kidney volume at birth reflected intra-uterine nephron mass and correlated positively with neonatal GFR; however, when adjusted for other covariants, only GA and mean arterial pressure remained significant determinants of GFR.17

In summary, despite its recognized shortcomings for neonatal use, SCr remains the renal biomarker clinical pharmacologists and physicians can rely upon until further research, validation, and standardization of novel biomarkers become available.

Estimation of GFR in Neonates

Measuring GFR in young infants is burdensome and highly impractical as a result of the difficulties of urine and blood collection and administration of exogenous markers in this vulnerable population. Therefore, estimation of GFR utilizing endogenous renal biomarkers and anthropometric measurements has become a useful tool in pediatric clinical practice. Nevertheless, given the unique physiology and ongoing maturation of neonates, the choice of renal biomarker, laboratory measurement method, anthropometric measurements, and gestational and postnatal age all require careful consideration.

Several GFR-estimating formulas have been developed over the past decades utilizing various anthropometric measurements, age, SCr, CysC, and other novel biomarkers, either alone or in combination. More recently, quantitative pharmacometric approaches, such as modeling and simulation, have also been used to optimize neonatal renal function assessment by accounting not only for organ function but also for size and maturation. In addition, renally eliminated drugs have been used to develop models of neonatal renal function.18

This article reviews SCr- and CysC-based GFR-estimating formulas developed for the pediatric population, with a special emphasis on their suitability for neonatal use.

Serum Creatinine–Based Formulas. Serum creatinine is the most extensively studied and therefore most widely used descriptor for evaluating GFR in neonates. Several SCr-based GFR-estimation formulas have been developed for pediatric use over the past decades (Table 1).

Table 1.

SCr-Based GFR-Estimating Equations Derived from Pediatric Patients *

| References | Equations | Age Range, yr (No. of Patients) | Health Status | SCr Assay |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schwartz19 | eGFR = 0.55 × Ht/SCr | 0.5–20 (186) |

CKD | Jaffe |

| Schwartz20 | eGFR = 0.45 × Ht/SCr | PNA: 0.013–1 GA: term (137) |

Healthy | Jaffe |

| Brion21 | eGFR = k × Ht/SCr k = 0.33 (preterm), k = 0.45 (term infants) |

PNA: 0–0.1 GA: 25–42 wks (202) |

Well baby/NICU | Jaffe |

| Modified (“bedside”) Schwartz22 | eGFR = k × Ht/SCr k = 0.413 |

1–16 (349) |

CKD | Enzymatic |

| Counahan23 | eGFR = k × Ht/SCr k = 0.43 |

0.167–14 (103) |

CKD | Jaffe |

| Flanders metadata24 | eGFR = k × Ht/SCr k = 0.0414 × ln[age] + 0.3018 |

0.083–14 (6734 SCr measurement) |

Healthy | Enzymatic |

| Léger26 | eGFR = (56.7 × Wt + 0.142 × Ht2)/SCr | 0.8–18 (64) |

CKD/Tx | Jaffe |

| British Columbia Children's 1 (BCCH1)27 | ln(eGFR) = 1.18 + (0.0016 × Wt) + (0.01 × Ht) + (149.5/SCr) - (2141/SCr2) | 1–19 (266) |

CKD | Enzymatic |

| British Columbia Children's 2 (BCCH2)27 | eGFR = −61.56 + [5886 × (1/SCr)] + [4.83 × age (yr)] + 10.02 (if male) |

1–19 (266) |

CKD | Enzymatic |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GA, gestational age (yr); Ht, body height or length (cm); NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; PNA, postnatal age (yr); SCr, serum creatinine (mg/dL); Tx, transplant; Wt, body weight (kg)

*All eGFR values are expressed in mL/(min × 1.73 m2), except for the Léger Formula, which is calculated in mL/min.

Schwartz 1976. Schwartz et al19 were the first who questioned the validity of the classical endogenous creatinine clearance (CrCL) formula in children in 1976. The classical CrCL equation states that CrCL = UCr × V/SCr, where UCr is urinary creatinine concentration in mg/dL, SCr is serum creatinine in mg/dL, and V is urinary flow rate expressed in mL/min. Schwartz et al19 argued that the numerator of the routinely used formula is the excretion rate of creatinine, which in a steady state must be equal to its rate of production. However, the rate of creatinine production is a function of muscle mass, which is related to body size, and therefore varies significantly in growing children. In addition, he highlighted that SCr concentrations change with age.19

In light of this, Schwartz et al19 conducted a study in 186 patients aged 6 months to 20 years and assessed the relationship between CrCL values and length, body surface area, age, and sex. In addition to blood samples, 3 to 5 consecutive urine specimens were collected from each patient every 20 to 30 minutes following an oral water load of 800 mL/1.73 m2. Regression equations were calculated by the method of least squares, and the correlation coefficient for body length per SCr (Ht/SCr) as a function of CrCL yielded the highest value. Therefore, the authors concluded that among the variables of body size tested, body height divided by SCr provided the best correlation with GFR, allowing accurate estimation of GFR without the need for any urinary marker measurement. Consequently, the derived formula is as follows:

Its application to clearance data in a separate group of 223 children revealed excellent agreement with GFR estimated by using both creatinine clearance (r = 0.935) or inulin clearance (r = 0.905). The authors19 did not find any significant differences between males and females or between prepubertal or postpubertal children.

Schwartz 1984. Eight years later, in 1984, Schwartz et al20 investigated the estimation of GFR in full-term infants during the first year of life. Serum creatinine was measured in 137 healthy infants (aged 5 days to 1 year), and CrCL studies were performed in 63 of them. The results revealed that the GFR estimation formula from Schwartz's previous work19 (eGFR = 0.55 × Ht/SCr) overestimated CrCL by 24% (p < 0.001) in this cohort. Based on the calculation of a new constant from k = CrCL × SCr/Ht, GFR was found to be more accurately estimated from the following:

In addition, the authors claimed that because the constant 0.45 and SCr do not change significantly during the first year of life, GFR can be approximated at the bedside from a single measurement of body length of the healthy full-term infant (GFR = 0.45 × Ht/0.39 = 1.1 × Ht).

Brion. Brion et al21 also explored the estimation of GFR in premature and low-birth-weight infants. The authors stated: “If the percent of body weight that is muscle can be determined in LBW [low birth weight] infants during the first year of life, it should be possible to predict the value of k for estimating GFR in such infants.” Therefore, a study was conducted in 118 preterm and 84 term infants to identify the correct k value for neonates and infants to use in the previously established eGFR = k × Ht/SCr equation (Equation 3).19 The patient population was divided into 3 GA groups—infants born at 25 to 28 weeks' GA, those born at 29 to 34 weeks' GA, and those born at 38 to 42 weeks' GA—and analyzed during the first 2 weeks of life, 2 to 8 weeks of life, and 8 weeks to 15 months of corrected age. The value of the k constant was determined by 2 methods: 1) the mean of the individual values of k from the formula k = GFR × SCr/Ht, where either inulin clearance or creatinine clearance was used as the value for the GFR, and 2) from the slope of the regression line of GFR versus Ht/SCr. The k value for preterm infants (0.34 ± 0.01 SE) was significantly less than that of term infants (0.43 ± 0.02, p < 0.001). There was no difference reported between 12- and 24-hour single-injection inulin clearance and 0.33 × Ht/SCr or creatinine clearance in preterm infants.

Furthermore, the body habitus of preterm and term infants was compared in the same study using the assessment of muscle mass from urinary creatinine excretion and from upper arm muscle area and volume and that of fatness from the sum of 5 skin-fold thickness measurements. Although premature infants had a lower percentage of muscle mass compared to term infants, they gained a relatively greater amount of subcutaneous fat over the first year of life. There was a very good correlation observed between arm muscle area or arm muscle volume and urinary creatinine excretion (r = 0.91 and 0.94, respectively) in 68 infants with heterogeneous body composition, indicating the validity of urinary creatinine measurement. Absolute GFR (mL/min) was also well estimated from arm muscle area or arm muscle volume factored by SCr. The authors concluded that GFR can be accurately estimated with a lower k value of 0.33 for all premature infants, taking into account the smaller muscle mass percentage in this neonatal subpopulation.

In summary, 2 studies conducted in the 1980s in both term20 and preterm21 infants led to the following GFR estimation formula:

where k = 0.33 for preterm infants, and k = 0.45 for term infants.

Of note, both of these studies used the Jaffe assay methodology to measure SCr values, and single-injection inulin was utilized to measure GFR.

Schwartz 2009. In order to avoid the protein interference characteristic of the Jaffe SCr assay methodology, the novel enzymatic method emerged in the early 1990s. Schwartz et al22 acknowledged the overestimation of GFR values by the Jaffe SCr measurement assay method and developed a new enzymatic assay–based GFR-estimating formula using the data from the baseline visits of 349 children (aged 1 to 16 years, median 10.8 years) in the Chronic Kidney Disease in Children (CKiD) study. CKiD is a National Institutes of Health–funded North American cohort study with the goal of characterizing progression and the effect of chronic kidney disease (CKD) on cardiovascular, growth, and behavioural indices in children and adolescents with mild to moderate CKD. In light of the above, body habitus of participants showed notable growth retardation (22.8 and 45.3 median age- and sex-specific height and weight percentile, respectively), characteristic of children with CKD. Iohexol plasma clearance was used to measure GFR.

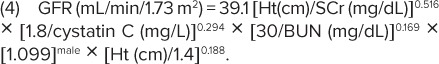

The final equation was derived based on height, serum creatinine, CysC (measured by immunoturbidimetry), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and sex, thus:

|

Linear regression analyses were performed to assess precision, goodness of fit, and accuracy of the equation. It yielded 87.7% of estimated GFR within 30% of the iohexol measured GFR and 45.6% within 10%. Moreover, the authors reported an updated bedside calculation that provided a good approximation of the above-described eGFR formula:

This equation is considered to be the “bedside Schwartz formula,” commonly used by physicians.

Counahan-Barratt Formula. Counahan et al23 investigated the relationship between SCr and GFR corrected for body surface area (BSA) in 103 children aged 2 months to 14 years with various renal diseases. 51Cr–ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) was used for GFR measurement and the Jaffe method was utilized for SCr assays. The authors performed multiple linear regression analysis and derived the following formula:

This formula was tested in a second group of 83 children and gave accurate results. Statistical comparison to the obtained 24-hour creatinine clearance values revealed the formula's superiority. Therefore, the authors concluded that the 24-hour creatinine clearance method should be abandoned in children, except in special circumstances.

Flanders Metadata. Pottel et al24 conducted a meta-analysis to evaluate the validity of the updated Schwartz equation22 and other available GFR-estimating formulas for healthy children. Serum creatinine data, demographic data, and GFR data were combined from 3 different independent studies to model uncorrected GFR (uGFR) and body surface area–corrected GFR (cGFR) for healthy children aged 1 month to 14 years. A total of 6734 enzymatic SCr values from the authors' hospital database were used to calculate median SCr values for each pediatric age group. Median length and weight values were obtained from sex- and age-specific growth curves of children in Flanders, Belgium. Median uncorrected GFR values were sourced from a study previously conducted by Piepsz et al.25 In addition, 182 children who underwent direct GFR measurement with 51Cr-EDTA because of underlying kidney pathology were used as the independent validation data set.

The authors demonstrated that for enzymatic SCr, the model for uncorrected GFR (uGFR = k′ × Ht3/SCr; k′ = 1.32 × 10−5) and the BSA-corrected GFR (cGFR = k × Ht/SCr), with an important age adaptation for k (k = 0.0414 × ln(age) + 0.3018), correlate well with 51Cr-EDTA GFR data for children 1 month to 14 years of age.

Léger Formula. Léger et al26 were the first to use the population pharmacokinetic approach to develop a GFR-estimation method in children. 51Cr-EDTA plasma concentrations from 64 children (aged 0.8–18 years) were analyzed using the non-linear mixed effects model program to explore the relationship between 51Cr-EDTA clearance (as a measurement of GFR) and patient characteristics. The most predictive equation was based on body weight, height, and SCr determined by the Jaffe method. Subsequently this formula was validated using data from 33 additional pediatric patients. The prediction was not improved by including patient age; however, addition of the length squared to the weight seemed to compensate for the non-proportionality between muscle mass and SCr with age. The final covariate model is as follows:

The authors acknowledged that their patient population had CKD and that the SCr Jaffe assay method may have introduced bias to their results.

British Columbia Children's Formulas 1 and 2. Mattman et al27 derived a GFR-estimation equation based on their local hospital laboratory methods and pediatric patient population. A retrospective review was conducted of all pediatric patients who were referred to the British Columbia Children's Hospital (BCCH) nephrology service from 1998 to 2003 and had both a 99mTc-DTPA nuclear GFR (nGFR) measurement and an enzymatic SCr measurement within 1 day of each other. Two hundred sixty-six (266) pediatric patients (aged 1 to 19 years) and 472 observations were included in the data set, which were then randomly assigned to a modelling (n = 180) or a validation (n = 86) group.

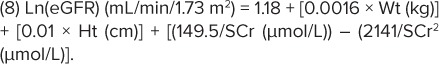

Two novel eGFR formulas were developed using data from the modeling data set. The first equation (BCCH1) utilized linear regression of the patient data onto nGFR and describes a quadratic relationship between the Ln(eGFR) and the inverse of the SCr value:

|

The second formula (BCCH2) was developed in an attempt to avoid the need for height and weight data, which are often missing in an outpatient laboratory setting.

Using data from the validation group, both of these formulas were compared to other GFR estimation equations; the modified bedside Schwartz formula (Equation 5) was reported as the most accurate with the least mathematical complexity in the clinical setting, followed by Equation 8 (BCCH1). However, if height is not available but laboratory data have been derived, then Equation 9 (BCCH2) is of value.

CysC–Based Formulas. Cystatin C may be a more appropriate endogenous biomarker than SCr for estimating GFR in neonates, given its minimal placental transfer, relatively constant production rate, and independence of inflammatory conditions, muscle mass, sex, body composition, and age. Moreover, subtle changes in GFR are more readily detected by CysC, given its shorter half-life compared to that of SCr.28 However, its high cost and lack of a standardized measurement method have prevented its widespread clinical use thus far.

Stickle et al29 measured plasma CysC, SCr, and inulin clearance in children with CKD aged 4 to 19 years. The authors reported that CysC concentration was reciprocally related to GFR and was broadly equivalent to SCr for estimation of GFR in pediatric patients.

In light of the above, several CysC-based formulas—used either alone or in combination with SCr and other biomarkers—have been developed to estimate GFR (Table 2).

Table 2.

CysC-Based GFR-Estimating Equations Derived from Pediatric Patients

| References | Equations | Age (range, yr) Patient No. | Health Status | Assay |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filler30 | eGFR = 91.62 × (CysC)−1.123 | 1–18 | CKD, Tx | Neph |

| N = 536 | ||||

| Grubb31 | eGFR = 84.69 × (CysC)−1.680 × 1.384if <14 yr | 0.3–18 | CKD | Turb |

| N = 85 | ||||

| Zappitelli32 | eGFR = 75.94/(CysC)1.17 × 1.2if Tx | 8–17 | CKD, Tx, spina bifida | Neph (SCr enzymatic) |

| eGFR = (43.82 × e0.003×Ht)/(CysC0.635 × SCr0.547) | N = 103 | |||

| Bouvet34 | eGFR (mL/min) = 63.2 × (SCr/1.086)−0.35 × | 1.4–22.8 | CKD | Neph (SCr Jaffe) |

| (CysC/1.2)−0.56 × (Wt/45)0.30 × (age/14)0.40 | N = 100 | |||

| Schwartz35 | eGFR = 39.8 [Ht/SCr]0.456 × [1.8/CysC]0.418 × | 1–16 | CKD | Neph |

| [ 30/BUN ]0.079 × [1.076]male × [Ht/1.4]0.179 | N = 349 |

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CysC, cystatin C; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; Ht, height; Neph, nephelometric CysC assay; SCr, serum creatinine; Turb, turbidimetric CysC assay; Tx, transplant

As is the case with SCr, CysC measurement methods (nephelometric versus turbidimetric) also need special consideration when using CysC-based GFR-estimating formulas. The nephelometric method is more sensitive and performs better in small sample volumes. Furthermore, despite recent efforts, CysC calibrations are not yet widely standardized and may overestimate true values.15

Filler Formula. Filler and Lepage30 validated a formula (Table 2) to estimate GFR from CysC, based on data from 536 children (aged 1 to 18 years) with various renal pathologies undergoing nuclear medicine GFR clearance studies with 99mTc-DTPA. Cystatin C was measured with nephelometric assay, and SCr for Schwartz GFR was calculated using the enzymatic method. Bland-Altman analysis revealed a trend toward overestimation of the GFR by the Schwartz formula with lower GFRs. However, when applied on the GFR estimate derived from the CysC formula, no overestimation was observed. The authors concluded that the novel CysC-based GFR estimate shows significantly less bias and therefore should be the preferred method in children. Nevertheless, the authors acknowledged the high cost of CysC assays compared to SCr (12-time difference) and called for worldwide CysC assay standardization.

Grubb Formula. Grubb et al31 constructed a CysC-based GFR-prediction equation using data from 536 patients aged 0.3 to 93 years of age, including 85 pediatric patients. The authors compared their CysC-based GFR predictions to those obtained with the Schwartz et al22 and Counahan et al23 formulas and found that the latter 2 equations overestimated GFR values. However, the authors acknowledged that this might be partially due to the fact that their SCr values relied on the enzymatic assay, whereas the Schwartz and Counahan formulas were derived using the Jaffe method.

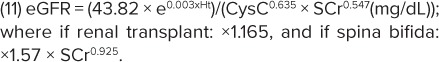

Zappitelli Formula. Zappitelli et al32 prospectively studied 103 pediatric patients (aged 8 to 17 years) undergoing iothalamate GFR testing. By using linear regression, 2 GFR-estimating equations were derived and compared to previously published formulae (Table 2; Filler, Grubb, Schwartz) using Bland-Altman analysis.

Cystatin C serum concentrations have been reported33 to be increased in renal transplant (RTx) recipient children compared with non-RTx children having the same GFR. In light of this, one of the equations derived by Zappitelli et al (CysCEq) used CysC values and presence/absence of renal transplant as covariates:

The authors' other equation combined enzymatic CysC and SCr values (CysCSCrEq) and also retained height, presence/absence of RTx, and spina bifida as covariates:

|

Comparison to previously published pediatric GFR formulae revealed that CysCEq and CysCSCrEq increased precision and sensitivity of GFR prediction and improved bias in subgroups of renal transplant recipients and patients with spina bifida.

Bouvet Formula. Bouvet et al34 also used a combination of CysC and SCr as covariates for GFR estimation. Plasma 51Cr-EDTA data from 100 children or young adults (1.4 to 22.8 years of age) were analyzed according to the population pharmacokinetic approach using the non-linear mixed effects model program. The actual 51Cr-EDTA clearance was compared to the clearance predicted according to different covariate equations. The best covariate equation was reported as follows:

The authors concluded that inclusion of CysC improves the estimation of GFR in children, if considered with the other covariates included in the mathematical formula.

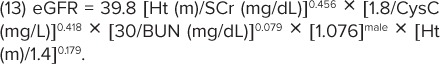

Schwartz Formula. Schwartz et al35 developed a GFR-estimating formula as part of the CKiD study, utilizing SCr, BUN, height, sex, and CysC measured by an immunoturbidimetric method; however, the correlation coefficient of CysC and GFR (−0.69) was less robust than expected. Therefore, 495 samples were reanalyzed using CysC immunonephelometry, and a new equation was derived:

|

The authors reported that the new equation showed high accuracy and precision and minimal bias in the CKiD cohort. However, further studies are considered necessary to evaluate its applicability in children with normal stature and muscle mass and higher GFR.

Discussion

In light of the above review of GFR-estimating formulas, it can be concluded that only the SCr-based methods of the Schwartz et al20 and Brion et al21 equations were derived from neonates (infants younger than 30 days). Moreover, only the Brion et al study included premature infants and accounted for variability of body mass within the neonatal cohort. However, the study's applicability to today's clinical practice is limited by the fact that SCr values were obtained using the Jaffe methodology rather than the enzymatic assay traceable to isotope dilution mass spectrometry. The CysC-based formulas reported to date (Table 2) have not been validated in neonates.

Abitbol et al17 conducted a study in 60 preterm and 40 term infants to distinguish between CysC and SCr as markers of estimated GFR (eGFR). Six equations derived from reference inulin, iohexol, and iothalamate clearance studies were used to calculate eGFR. The authors reported that GFR-estimating formulae based on SCr alone consistently underestimated GFR, whereas CysC and combined CysC+SCr equations were more consistent with referenced inulin clearance studies.

In a more recent study, Treiber et al36 enrolled 50 full-term SGA and 50 appropriate for GA newborns to compare CysC, SCr, and total kidney volume at birth and at 3 days of age. Cystatin C and SCr values did not differ significantly between the 2 groups of SGA and appropriate for GA infants. Three-dimensional ultrasound correlated significantly with the cord-blood CysC measurements; however, it did not show any link with cord-blood SCr values, while 2-dimensional ultrasound correlated with neither of these 2 parameters. A 10% reduction in kidney volume was associated with an increase in CysC value of 9.3% in cord blood. In addition, the collected CysC and SCr levels were compared to previously published GFR-estimating formulas (Zappitelli CysC, Schwartz CysC 2012, Filler CysC, Schwartz SCr 1986 and 2009, Zappitelli CysC+SCr combined, and Schwartz CysC+SCr+BUN combined). The SCr-based and Schwartz combined equations underestimated GFR relative to CysC-based and Zappitelli-based equations both at birth and at 3 days. Although it was not among the study objectives, the authors derived a new GFR-estimation formula for newborns, utilizing kidney volume (Vol-T: result of 3-dimensional volumetry) and BSA:

This equation may represent a significant step forward toward accurately assessing GFR in newborns; however, it requires further validation with inulin clearance.37

Conclusions

Our review provides an overview of the currently available renal biomarker–based GFR-estimating methods used in the pediatric population. Despite its well-recognized limitations, SCr remains the renal biomarker upon which clinical pharmacologists and clinicians have primarily relied for estimating GFR in neonates. Several SCr-based GFR-estimation formulas have been developed for pediatric use; however, only one of these was derived from preterm and term neonates by Brion et al21 in 1986. In light of this, the Brion et al formula (eGFR = k × Ht/SCr, k = 0.33 [preterm], k = 0.45 [term infants]) is considered the most appropriate for estimating GFR in the neonatal population. However, given that the formula was developed over 30 years ago, the authors used the Jaffe SCr assay method, and therefore conversion to enzymatic-based SCr values may be needed. When converting SCr values from Jaffe to the enzymatic method, or vice versa, Srivastava et al.38 provide recommendations.

Correct alignment of SCr assay methods between local laboratories and the utilized GFR-estimating formula is considered crucial, as results may vary significantly and potentially mislead physicians. Furthermore, recent studies in neonates suggest that SCr-based equations may underestimate GFR in this population, most likely as a result of extreme low values. Cystatin C–based equations (either alone or in combination with other biomarkers) seem to yield a better fit; however, they require further validation in infants younger than 1 month of age.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BCCH

British Columbia Children's Hospital

- BSA

body surface area

- BUN

blood urea nitrogen

- cGFR

corrected GFR

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- CKiD

Chronic Kidney Disease in Children study

- CrCL

creatinine clearance

- CysC

cystatin C

- EDTA

ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- GA

gestational age

- GFR

glomerular filtration rate

- Ht

height

- k

constant for association of GFR, laboratory measurements, and anthropometric measurement

- nGFR

nuclear GFR

- RTx

renal transplant

- SCr

serum creatinine

- SGA

small for gestational age

- UCr

urinary creatinine concentration

- uGFR

uncorrected GFR

Footnotes

Disclaimer The opinions expressed are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as the position of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Disclosure The authors declare no conflicts or financial interest in any product or service mentioned in the manuscript, including grants, equipment, medications, employment, gifts, and honoraria.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abitbol CL, DeFreitas MJ, Strauss J. Assessment of kidney function in preterm infants: lifelong implications. Pediatr Nephrol. 2016;31(12):2213–2222. doi: 10.1007/s00467-016-3320-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tufro A, Gulati A. Development of glomerular circulation and function. In: Avner ED, Harmon WE, Niaudet P, editors. Pediatric Nephrology. 7th ed. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2016. pp. 37–59. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tayman C, Rayyan M, Allegaert K. Neonatal pharmacology: extensive interindividual variability despite limited size. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2011;16(3):170–184. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-16.3.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sutherland MR, Gubhaju L, Moore L et al. Accelerated maturation and abnormal morphology in the preterm neonatal kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(7):1365–1374. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010121266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez MM, Gomez AH, Abitbol CL et al. Histomorphometric analysis of postnatal glomerulogenesis in extremely preterm infants. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2004;7(1):17–25. doi: 10.1007/s10024-003-3029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allegaert K, Anderson BJ, van den Anker JN et al. Renal drug clearance in preterm neonates: relation to prenatal growth. Ther Drug Monit. 2007;29(3):284–291. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e31806db3f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schreuder MF, Bueters RRG, Allegaert K. The interplay between drugs and the kidney in premature neonates. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;29(11):2083–2091. doi: 10.1007/s00467-013-2651-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drukker A, Guignard JP. Renal aspects of the term and preterm infant: a selective update. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2002;14(2):175–182. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200204000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stonestreet BS, Bell EF, Oh W. Validity of endogenous creatinine clearance in low birthweight infants. Pediatr Res. 1979;13(9):1012–1014. doi: 10.1203/00006450-197909000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van den Anker JN, de Groot R, Broerse HM et al. Assessment of glomerular filtration rate in preterm infants by serum creatinine: comparison with inulin clearance. Pediatrics. 1995;96(6):1156–1158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boer DP, de Rijke YB, Hop WC et al. Reference values for serum creatinine in children younger than 1 year of age. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25(10):2107–2113. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1533-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoseini R, Otukesh H, Rahimzadeh N et al. Glomerular function in neonates. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2012;6(3):166–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Creatinine Standardization. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-communication-programs/nkdep/lab-evaluation/gfr/creatinine-standardization/Pages/creatinine-standardization.aspx Accessed October 19, 2018.

- 14.Allegaert K, Mekahli D, van den Anker J. Cystatin C in newborns: a promising renal biomarker in search for standardization and validation. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28(15):1833–1838. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.969236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bargnoux AS, Piéroni L, Cristol JP et al. Multicenter evaluation of cystatin C measurement after assay standardization. Clin Chem. 2017;63(4):833–841. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2016.264325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shiki Y, Shimoya K, Tokugawa Y et al. Changes of lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase level during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2004;30(1):65–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1341-8076.2004.00158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abitbol CL, Seeherunvong W, Galarza MG et al. Neonatal kidney size and function in preterm infants: what is a true estimate of glomerular filtration rate? J Pediatr. 2014;164(5):1026–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilbaux M, Fuchs A, Samardzic J et al. Pharmacometric approaches to personalize use of primarily renally eliminated antibiotics in preterm and term neonates. J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;56(8):909–935. doi: 10.1002/jcph.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwartz GJ, Haycock GB, Edelmann CM et al. A simple estimate of glomerular filtration rate in children derived from body length and plasma creatinine. Pediatrics. 1976;58(2):259–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz GJ, Feld LG, Langford DJ. A simple estimate of glomerular filtration rate in full-term infants during the first year of life. J Pediatr. 1984;104(6):849–854. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(84)80479-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brion LP, Fleischman AR, McCarton C et al. A simple estimate of glomerular filtration rate in low birth weight infants during the first year of life: noninvasive assessment of body composition and growth. J Pediatr. 1986;109(4):699. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80245-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz GJ, Muñoz A, Schneider MF et al. New equations to estimate GFR in children with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(3):629–637. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008030287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Counahan R, Chantler C, Ghazali S et al. Estimation of glomerular filtration rate from plasma creatinine concentration in children. Arch Dis Child. 1976;51(11):875–878. doi: 10.1136/adc.51.11.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pottel H, Mottaghy FM, Zaman Z et al. On the relationship between glomerular filtration rate and serum creatinine in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25(5):927–934. doi: 10.1007/s00467-009-1389-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piepsz A, Tondeur M, Ham H. Escaping the correction for body surface area when calculating glomerular filtration rate in children. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35(9):1669–1672. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0820-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Léger F, Bouissou F, Coulais Y, Tafani M et al. Estimation of glomerular filtration rate in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2002;17(11):903–907. doi: 10.1007/s00467-002-0964-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mattman A, Eintracht S, Mock T et al. Estimating pediatric glomerular filtration rates in the era of chronic kidney disease staging. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(2):487–496. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dworkin LD. Serum cystatin C as a marker of glomerular filtration rate. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2001;10(5):551–553. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200109000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stickle D, Cole B, Hock K et al. Correlation of plasma concentrations of cystatin C and creatinine to inulin clearance in a pediatric population. Clin Chem. 1998;44(6 Pt 1):1334–1338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Filler G, Lepage N. Should the Schwartz formula for estimation of GFR be replaced by cystatin C formula? Pediatr Nephrol. 2003;18(10):981–985. doi: 10.1007/s00467-003-1271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grubb A, Nyman U, Björk J et al. Simple cystatin C-based prediction equations for glomerular filtration rate compared with the modification of diet in renal disease prediction equation for adults and the Schwartz and the Counahan-Barratt prediction equations for children. Clin Chem. 2005;51(8):1420–1431. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.051557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zappitelli M, Parvex P, Joseph L et al. Derivation and validation of cystatin C-based prediction equations for GFR in children. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48(2):221–230. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.04.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bökenkamp A, Domanetzki M, Zinck R et al. Cystatin C serum concentrations underestimate glomerular filtration rate in renal transplant recipients. Clin Chem. 1999;45(10):1866–1868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bouvet Y, Bouissou F, Coulais Y et al. GFR is better estimated by considering both serum cystatin C and creatinine levels. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21(9):1299–1306. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0145-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwartz GJ, Schneider MF, Maier PS et al. Improved equations estimating GFR in children with chronic kidney disease using an immunonephelometric determination of cystatin C. Kidney Int. 2012;82(4):445–453. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Treiber M, Pecovnik Balon B, Gorenjak M. A new serum cystatin C formula for estimating glomerular filtration rate in newborns. Pediatr Nephrol. 2015;30(8):1297–1305. doi: 10.1007/s00467-014-3029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Filler G. A step forward towards accurately assessing glomerular filtration rate in newborns. Pediatr Nephrol. 2015;30(8):1209–1212. doi: 10.1007/s00467-014-3014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Srivastava T, Alon US, Althahabi R et al. Impact of standardization of creatinine methodology on the assessment of glomerular filtration rate in children. Pediatr Res. 2009;65(1):113–116. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318189a6e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]