Abstract

Reliable governance and health financing are critical to the abilities of health systems in different countries to sustainably meet the health needs of their peoples, including those with kidney disease. A comprehensive understanding of existing systems and infrastructure is therefore necessary to globally identify gaps in kidney care and prioritize areas for improvement. This multinational, cross-sectional survey, conducted by the ISN as part of the Global Kidney Health Atlas, examined the oversight, financing, and perceived quality of infrastructure for kidney care across the world. Overall, 125 countries, comprising 93% of the world’s population, responded to the entire survey, with 122 countries responding to questions pertaining to this domain. National oversight of kidney care was most common in high-income countries while individual hospital oversight was most common in low-income countries. Parts of Africa and the Middle East appeared to have no organized oversight system. The proportion of countries in which health care system coverage for people with kidney disease was publicly funded and free varied for AKI (56%), nondialysis chronic kidney disease (40%), dialysis (63%), and kidney transplantation (57%), but was much less common in lower income countries, particularly Africa and Southeast Asia, which relied more heavily on private funding with out-of-pocket expenses for patients. Early detection and management of kidney disease were least likely to be covered by funding models. The perceived quality of health infrastructure supporting AKI and chronic kidney disease care was rated poor to extremely poor in none of the high-income countries but was rated poor to extremely poor in over 40% of low-income countries, particularly Africa. This study demonstrated significant gaps in oversight, funding, and infrastructure supporting health services caring for patients with kidney disease, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

Keywords: developing countries, delivery of health care, global health care, global health governance, health care financing, nephrology

Health system oversight and financing are key determinants of the quality, efficiency, and equity of health care delivery.1 Beyond overseeing the routine functioning and performance of health services, oversight is critical to their strategic development, regulation, and accountability. It shapes the capacity of health systems to develop and implement policies, identify and correct service deficiencies, advocate for health care in national development, and collaborate with stakeholders. Governance bodies should seek to achieve universal health coverage, which requires robust health financing systems.2, 3, 4 In addition to generating sufficient funds to support the health system, financing systems must allow central pooling of funds for financial risk protection and facilitate equitable allocation of resources to areas of greatest need.

Due to differences in infrastructure and economy, significant global variability is expected in health system oversight and financing. In low-income countries, government contributions are less likely to be sufficient to fund health care, creating reliance on supplemental funding from external sources, including nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), community organizations, and private health insurance. Despite these contributions, resources may remain insufficient to ensure financial risk protection, and the monetary burden may be transferred to patients.5 Lack of resources also compromises the adequacy of health service infrastructure and leads to low-quality health care delivery.6

The escalating prevalence and associated cost of kidney disease mandates a complete understanding of existing oversight and financing systems to drive effective, efficient, and sustainable service delivery. As the oversight and financing of health services caring for patients with kidney disease have not been previously reported, the present study was performed to examine health system oversight, financing, and infrastructural quality for delivering kidney care across International Society of Nephrology (ISN) regions7 and 2014 World Bank country classification as low-, lower middle-, upper middle-, and high-income nations.8

Results

Of the 130 countries surveyed, 125 countries participated (comprising 93% of the world’s population) and 122 countries provided data pertaining to health system oversight and financing (97% response rate).

Health system oversight

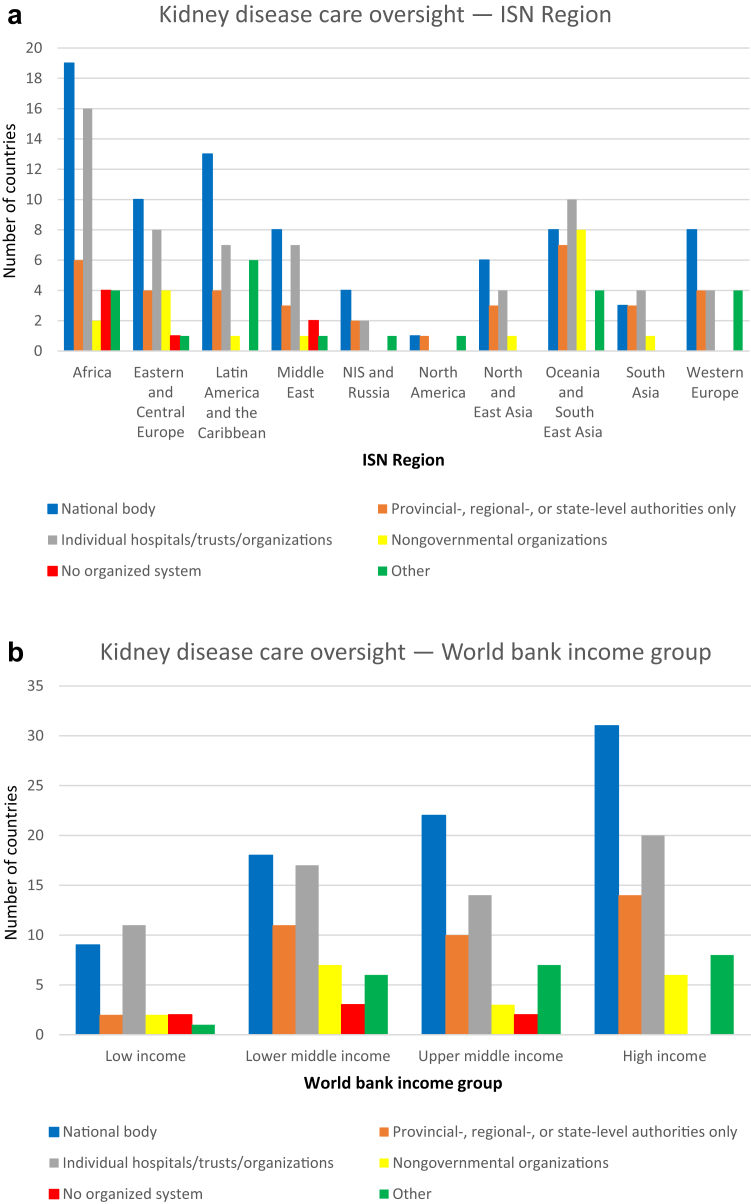

Health system oversight of kidney care was performed by a national body in the majority of countries (n = 80, 66%). The highest proportions were reported from North and East Asia (n = 6, 100%) and Latin America and the Caribbean (n = 13, 81%) (Figure 1a). There were no appreciable differences in the frequencies of national oversight of kidney care between high-, upper middle-, lower middle-, and low-income countries (Figure 1b). Kidney care was managed at a provincial or regional level in 30% (n = 37) of countries and by NGOs in 15% of countries (n = 18). Oversight by NGOs was particularly common in low-income countries and in Oceania and Southeast Asia. Approximately one-half of countries (n = 62, 51%) relied on individual hospitals, trusts, or organizations to oversee governance. This approach was most common in low-income countries. Six percent (n = 7) of countries had no organized system for managing kidney care.

Figure 1.

Oversight of kidney care in 122 countries grouped according to (a) International Society of Nephrology (ISN) region and (b) World Bank income group. NIS, Newly Independent States.

Health system financing

Only 19% (n = 23) of countries reported that their health system was publicly funded by government with no fees at the point of delivery (Table 1). An additional 24% (n = 28) of countries publicly funded their health system, but with fees at point of delivery. This approach was particularly common for low-income countries (n = 7, 41%). Nearly one-half (n = 52, 44%) of countries reported a mix of public and private funding, especially among high-income countries. Health systems of 13% (n = 16) of countries were funded through multiple sources, including government, NGOs, and community organizations. All residents were eligible for health coverage in more than one-half of respondent countries (n = 69, 58%). This proportion was similar across income groups. Newly Independent States (of the former Soviet Union) and Russian (5 of 6, 83%) countries had the highest rates of health coverage to their residents, while South Asian (2 of 5, 40%) countries had the lowest rates (Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of health care system coverage and funding mechanism in 119 countries grouped according to ISN region and World Bank income group

| Region/group | Publicly funded by government; free at the point of delivery | Publicly funded by government but with some fees at the point of delivery | Mix of public and private funding systems | Solely private and out of pocket | Multiple systems programs provided by government, NGOs, and communities | Universal coverage (n = 118) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, all residents are included in the coverage | No, not all residents are included | ||||||

| Overall | 23 (19) | 28 (24) | 52 (44) | 0 (0) | 16 (13) | 69 (58) | 49 (42) |

| ISN region | |||||||

| Africa | 5 (15) | 13 (38) | 9 (26) | 0 (0) | 7 (21) | 19 (56) | 15 (44) |

| Eastern and Central Europe | 8 (47) | 6 (35) | 2 (12) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 12 (71) | 5 (29) |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 2 (15) | 0 (0) | 11 (85) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9 (69) | 4 (31) |

| Middle East | 2 (15) | 1 (8) | 8 (62) | 0 (0) | 2 (15) | 6 (46) | 7 (54) |

| NIS and Russia | 2 (33) | 0 (0) | 3 (50) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) | 5 (83) | 1 (17) |

| North America | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) |

| North and East Asia | 0 (0) | 2 (33) | 4 (67) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (50) | 3 (50) |

| Oceania and South East Asia | 0 (0) | 3 (23) | 9 (69) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 6 (50) | 6 (50) |

| South Asia | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (40) | 0 (0) | 3 (60) | 2 (40) | 3 (60) |

| Western Europe | 4 (40) | 3 (30) | 2 (20) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | 6 (60) | 4 (40) |

| World Bank income group | |||||||

| Low income | 2 (12) | 7 (41) | 3 (18) | 0 (0) | 5 (29) | 9 (53) | 8 (47) |

| Lower middle income | 2 (6) | 9 (27) | 16 (48) | 0 (0) | 6 (18) | 19 (59) | 13 (41) |

| Upper middle income | 9 (29) | 4 (13) | 15 (48) | 0 (0) | 3 (10) | 17 (55) | 14 (45) |

| High income | 10 (26) | 8 (21) | 18 (47) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 24 (63) | 14 (37) |

ISN, International Society of Nephrology; NGOs, nongovernmental organizations; NIS, Newly Independent States. Values are n (%).

Overall, in a publicly funded health care system, the majority of high-income countries publically financed all aspects of kidney care including dialysis, transplantation, management of chronic kidney disease (CKD) complications, management to reduce risk of CKD progression, early detection in individuals at risk, and management of acute kidney injury (AKI) (Table 2). Thirteen percent (n = 2) of low-, 19% (n = 6) of lower middle-, 40% (n = 12) of upper middle-, and 54% (n = 19) of high-income countries funded all aspects of kidney care.

Table 2.

Health care system coverage for care of patients with kidney disease in 122 countries grouped according to ISN region and World Bank income group

| Region/group | Nondialysis CKD (n = 119) |

Dialysis (n = 122) |

Kidney transplantation (n = 112) |

AKI (n = 119) |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publicly funded by government, free at the point of delivery | Publicly funded by government, some fees at delivery | A mix of publicly funded and private systems | Solely private and out of pocket | Solely private through health insurance providers | Publicly funded by government, free at the point of delivery | Publicly funded by government, some fees at delivery | A mix of publicly funded and private systems | Solely private and out of pocket | Solely private through health insurance providers | Publicly funded by government, free at the point of delivery | Publicly funded by government, some fees at delivery | A mix of publicly funded and private systems | Solely private and out of pocket | Solely private through health insurance providers | Publicly funded by government, free at the point of delivery | Publicly funded by government, some fees at delivery | A mix of publicly funded and private systems | Solely private and out of pocket | Solely private through health insurance providers | |

| Overall | 48 (40) | 50 (42) | 61 (51) | 14 (12) | 8 (7) | 77 (63) | 40 (33) | 52 (43) | 13 (11) | 10 (8) | 64 (57) | 35 (31) | 43 (38) | 18 (16) | 8 (7) | 67 (56) | 43 (36) | 56 (47) | 11 (9) | 6 (5) |

| ISN region | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Africa | 10 (29) | 14 (41) | 15 (44) | 7 (21) | 4 (12) | 13 (38) | 14 (41) | 12 (35) | 7 (21) | 4 (12) | 10 (37) | 3 (11) | 9 (33) | 11 (41) | 3 (11) | 13 (39) | 13 (39) | 15 (45) | 5 (15) | 3 (9) |

| Eastern and Central Europe | 12 (75) | 5 (31) | 2 (13) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 16 (94) | 1 (6) | 2 (12) | 1 (6) | 2 (12) | 16 (94) | 2 (12) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 16 (94) | 1 (6) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 7 (47) | 5 (33) | 12 (80) | 1 (7) | 2 (13) | 11 (69) | 6 (38) | 12 (75) | 2 (13) | 3 (19) | 8 (53) | 7 (47) | 12 (80) | 2 (13) | 3 (20) | 8 (53) | 6 (40) | 12 (80) | 1 (7) | 2 (13) |

| Middle East | 5 (38) | 6 (46) | 8 (62) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (77) | 3 (23) | 7 (54) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (62) | 6 (46) | 6 (46) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (46) | 5 (38) | 7 (54) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| NIS and Russia | 1 (17) | 2 (33) | 4 (67) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 6 (100) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (67) | 2 (33) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 4 (67) | 3 (50) | 2 (33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| North America | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| North and East Asia | 2 (33) | 6 (100) | 3 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (67) | 5 (83) | 3 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (33) | 6 (100) | 2 (33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (67) | 5 (83) | 3 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Oceania and Southeast Asia | 3 (23) | 7 (54) | 9 (69) | 2 (15) | 1 (8) | 4 (31) | 6 (46) | 9 (69) | 2 (15) | 1 (8) | 5 (42) | 5 (42) | 8 (67) | 3 (25) | 2 (17) | 6 (46) | 7 (54) | 9 (69) | 3 (23) | 1 (8) |

| South Asia | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 4 (100) | 2 (50) | 0 (0) | 3 (60) | 2 (40) | 3 (60) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | 2 (50) | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 3 (75) | 2 (50) | 0 (0) |

| Western Europe | 6 (60) | 4 (40) | 3 (30) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (80) | 2 (20) | 2 (20) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (80) | 2 (20) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (80) | 2 (20) | 3 (30) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| World Bank income group | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Low income | 4 (24) | 8 (47) | 5 (29) | 5 (29) | 1 (6) | 5 (29) | 10 (59) | 5 (29) | 5 (29) | 1 (6) | 2 (17) | 1 (8) | 1 (8) | 8 (67) | 2 (17) | 5 (33) | 6 (40) | 6 (40) | 5 (33) | 0 (0) |

| Lower middle income | 4 (13) | 14 (45) | 22 (71) | 7 (23) | 4 (13) | 17 (50) | 12 (35) | 17 (50) | 7 (21) | 4 (12) | 9 (31) | 11 (38) | 17 (59) | 8 (28) | 2 (7) | 10 (30) | 17 (52) | 19 (58) | 5 (15) | 3 (9) |

| Upper middle income | 18 (56) | 13 (41) | 16 (50) | 1 (3) | 3 (9) | 24 (75) | 7 (22) | 14 (44) | 1 (3) | 3 (9) | 22 (69) | 13 (41) | 13 (41) | 2 (6) | 4 (13) | 23 (72) | 9 (28) | 14 (44) | 1 (3) | 3 (9) |

| High income | 22 (56) | 15 (38) | 18 (46) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 31 (79) | 11 (28) | 16 (41) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 31 (79) | 10 (26) | 12 (31) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 29 (74) | 11 (28) | 17 (44) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

AKI, acute kidney injury; CKD, chronic kidney disease; ISN, International Society of Nephrology; NIS, Newly Independent States. Values are n (%).

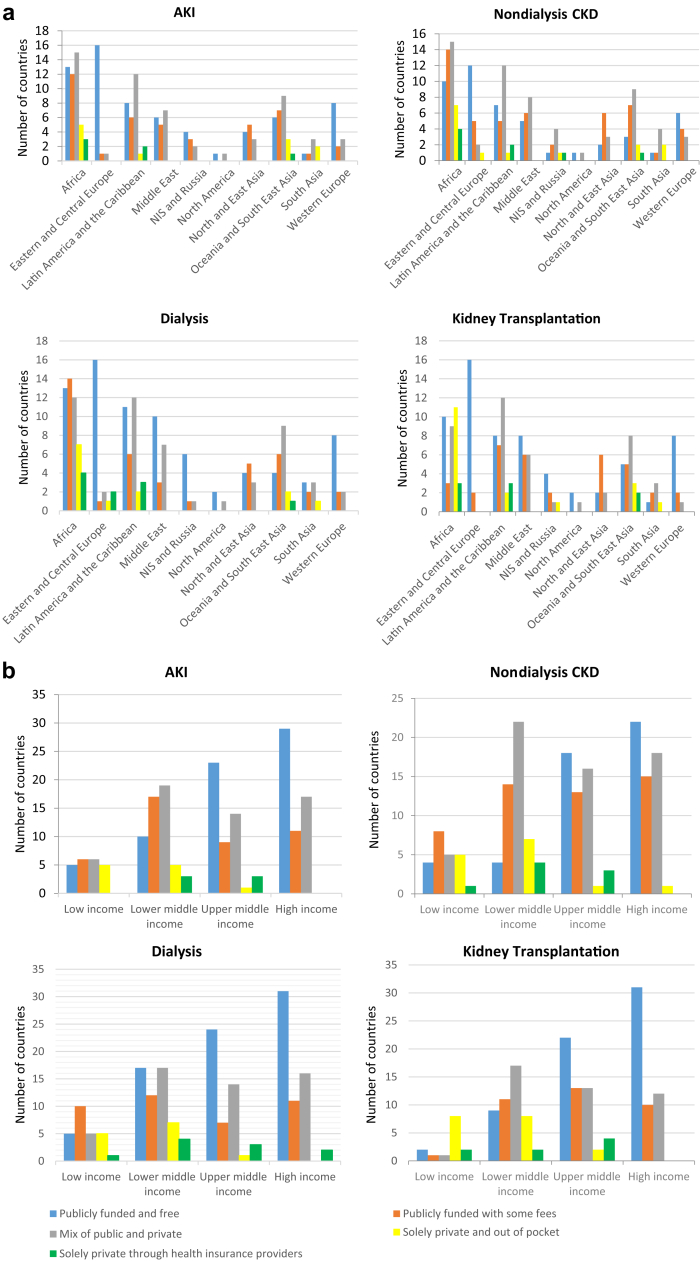

Nondialysis CKD funding

Care for patients with nondialysis CKD was primarily funded by a mixture of public and private sources (n = 61, 51%). Publicly funded care that was free at the point of delivery was overall less common for nondialysis CKD than for any of the other types of kidney care (AKI, dialysis, kidney transplantation) (Table 2, Figure 2a and b). Lower income countries more frequently relied on solely private funding for nondialysis CKD care (Figure 2b). Countries in Eastern and Central Europe (n = 12, 75%) had the highest rate of free, publicly funded care for patients with nondialysis CKD, and Oceanian and Southeast Asian countries (n = 3, 23%) had the lowest. Early detection of kidney disease in high-risk individuals was often excluded from public funding (n = 58, 50%) (Table 3). Similarly, early management to reduce the risk of CKD progression was frequently not covered (n = 47, 40%), nor was general CKD management (n = 46, 39%) or management of CKD complications (e.g., anemia, bone disease, malnutrition) (n = 46, 39%) (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Health care system coverage for care of patients with kidney disease in 122 countries grouped according to the (a) International Society of Nephrology (ISN) region (nAKI= 119, nnondilaysis CDK= 119, ndialysis= 122, nkidney transplantation= 112) and (b) World Bank income group. AKI, acute kidney injury; CKD, chronic kidney disease; NIS, Newly Independent States.

Table 3.

Aspects of kidney care not included in public coverage in 117 countries grouped according to ISN region and World Bank income group

| Region/group | Dialysis | Transplantation | Management of CKD complications (anemia, bone disease, malnutrition) | Management to reduce risk of CKD progression (risk factor control) | Early management to reduce risk of CKD progression (risk factor control) | Early detection in individuals at risk | Management of AKI | None—all aspects funded | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 33 (28) | 41 (35) | 46 (39) | 46 (39) | 47 (40) | 58 (50) | 28 (24) | 32 (27) | 39 (33) |

| ISN region | |||||||||

| Africa | 12 (35) | 19 (56) | 19 (56) | 14 (41) | 12 (35) | 18 (53) | 9 (26) | 5 (15) | 14 (41) |

| Eastern and Central Europe | 1 (6) | 1 (6) | 1 (6) | 3 (18) | 4 (24) | 3 (18) | 1 (6) | 12 (71) | 1 (6) |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 5 (38) | 7 (54) | 6 (46) | 6 (46) | 7 (54) | 7 (54) | 4 (31) | 4 (31) | 4 (31) |

| Middle East | 2 (15) | 1 (8) | 2 (15) | 3 (23) | 4 (31) | 6 (46) | 1 (8) | 5 (38) | 5 (38) |

| NIS and Russia | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (33) | 3 (50) | 3 (50) | 4 (67) | 2 (33) | 1 (17) | 2 (33) |

| North America | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) |

| North and East Asia | 2 (33) | 2 (33) | 3 (50) | 1 (17) | 2 (33) | 3 (50) | 2 (33) | 0 (0) | 4 (67) |

| Oceania and Southeast Asia | 7 (54) | 7 (54) | 7 (54) | 7 (54) | 7 (54) | 8 (62) | 5 (38) | 2 (15) | 5 (38) |

| South Asia | 2 (40) | 2 (40) | 3 (60) | 4 (80) | 3 (60) | 3 (60) | 2 (40) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) |

| Western Europe | 1 (13) | 1 (13) | 1 (13) | 3 (38) | 3 (38) | 4 (50) | 1 (13) | 3 (38) | 2 (25) |

| World Bank income group | 33 (28) | 41 (35) | 46 (39) | 46 (39) | 47 (40) | 58 (50) | 28 (24) | 32 (27) | 39 (33) |

| Low income | 9 (53) | 11 (65) | 11 (65) | 9 (53) | 8 (47) | 11 (65) | 8 (47) | 2 (12) | 8 (47) |

| Lower middle income | 9 (27) | 16 (48) | 18 (55) | 19 (58) | 19 (58) | 19 (58) | 8 (24) | 4 (12) | 11 (33) |

| Upper middle income | 8 (26) | 8 (26) | 11 (35) | 10 (32) | 11 (35) | 14 (45) | 7 (23) | 10 (32) | 9 (29) |

| High income | 7 (19) | 6 (17) | 6 (17) | 8 (22) | 9 (25) | 14 (39) | 5 (14) | 16 (44) | 11 (31) |

AKI, acute kidney injury; CKD, chronic kidney disease; ISN, International Society of Nephrology; NIS, Newly Independent States. Values are n (%).

Dialysis funding

Across all countries, dialysis was primarily funded by government with no fees to patients at the point of delivery (n = 77, 63%) (Table 2). Countries in Newly Independent States and Russia (n = 6, 100%) had the highest rate of free, publicly funded care for patients requiring dialysis, while Oceanian and Southeast Asian countries (n = 4, 31%) had the lowest. Compared with high-income countries, low-income countries were more likely to require financial contribution from patients at the point of service delivery in addition to government funding (Figure 2b).

Kidney transplantation funding

Kidney transplantation was publicly funded with no out-of-pocket fees in 57% of countries (Table 2). Countries in Eastern and Central Europe (n = 16, 94%) had the highest rate of free, publicly funded care for patients requiring kidney transplantation, while South Asian countries (n = 1, 25%) had the lowest. The proportion of countries with public funding for kidney transplantation was significantly greater for high-income countries (n = 31, 79%) than for low-income countries (n = 2, 17%). Low-income countries (n = 8, 67%) had the highest proportion of solely private and out-of-pocket funding for kidney transplantation.

AKI funding

Funding for care of patients with AKI was predominantly from public sources (Table 2). Countries in Eastern and Central Europe (n = 16, 94%) had the highest rates of free, publicly funded care for patients with AKI, while South Asian countries (n = 1, 25%) had the lowest. Low-income countries were more likely to require either a financial contribution from patients in addition to government funding or solely private funding from patients.

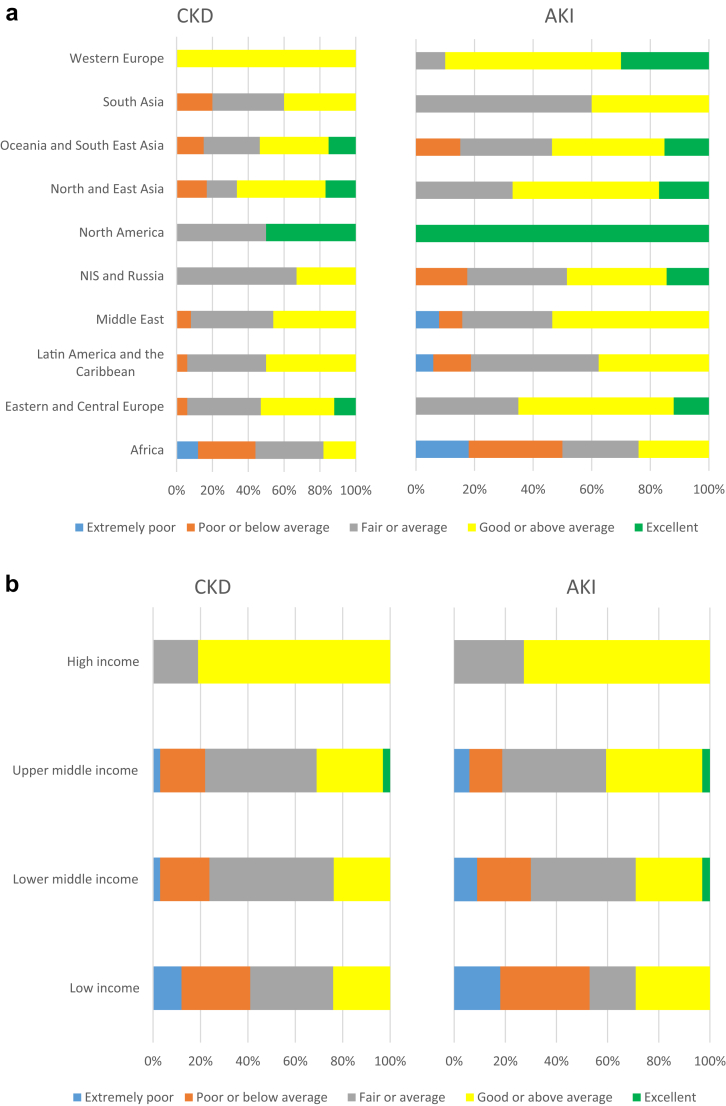

Health care infrastructure for CKD/AKI care

Overall, 45% of countries (n = 55) reported at least good or above average infrastructure for CKD care, and 48% of countries (n = 59) reported at least good or above average infrastructure for AKI care (Figure 3a). Countries in Western Europe had the highest rates of perceived above average or excellent infrastructures for CKD and AKI care, while African countries had the lowest (Figure 3a). The majority of high-income countries rated the quality of their CKD and AKI infrastructures as above average or excellent (Figure 3b). The quality of health infrastructures supporting AKI and CKD care were rated poor to extremely poor in none of high-income countries but in over 40% of low-income countries (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Rating of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and acute kidney injury (AKI) care health infrastructure in 122 countries grouped according to (a) International Society of Nephrology (ISN) region and (b) World Bank income group. NIS, Newly Independent States.

Within-country kidney care variation

More than one-half of the surveyed countries (n = 80, 66%) reported clinically important variations in kidney care delivery among different regions, states, or provinces within their countries. These variations were particularly prominent in low- (n = 15, 88%) and lower middle- (n = 32, 91%) income countries. Among ISN regions, South Asian countries (n = 5, 100%) had the highest reported within-country kidney care variation, followed by African countries (n = 30, 88%). Eastern and Central European countries reported the least within-country kidney care variation, with 82% (n = 14) reporting no clinically important variation (Table 4).

Table 4.

Within-country kidney care variation in 122 countries grouped according to ISN region and World Bank income group

| Region/group | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 80 (66) | 42 (34) |

| ISN region | ||

| Africa | 30 (88) | 4 (12) |

| Eastern and Central Europe | 3 (18) | 14 (82) |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 11 (69) | 5 (31) |

| Middle East | 8 (62) | 5 (38) |

| NIS and Russia | 4 (67) | 2 (33) |

| North America | 1 (50) | 1 (50) |

| North and East Asia | 3 (50) | 3 (50) |

| Oceania and Southeast Asia | 11 (85) | 2 (15) |

| South Asia | 5 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Western Europe | 4 (40) | 6 (60) |

| World Bank income group | ||

| Low income | 15 (88) | 2 (12) |

| Lower middle income | 31 (91) | 3 (9) |

| Upper middle income | 20 (63) | 12 (38) |

| High income | 14 (36) | 25 (64) |

ISN, International Society of Nephrology; NIS, Newly Independent States. Values are n (%).

Discussion

This study identified important variability in health system oversight, financing, and infrastructural quality for kidney care across ISN regions and World Bank income groups, as well as across regions, states, or provinces within countries. Overall, health systems were most frequently governed by national bodies. Oversight was fragmented in low-income countries, with individual hospitals, trusts, or organizations providing their own oversight. Provincial, regional, or state oversight was more common in high-income countries. Government funding was available for dialysis in all income groups but was associated with additional out-of-pocket expenses to patients in low-income countries. Kidney transplantation was also generally funded privately in low-income countries. Care for patients with nondialysis CKD and AKI was publicly funded in high-income countries and privately funded in low-income countries. Nondialysis CKD care, including early detection and management, was less likely to be publicly funded and free at the point of delivery, than were AKI, dialysis, and kidney transplant care. Universal health coverage—equal access to all required health services by the public without enduring financial burden9—was available in only a minority of countries. Infrastructures for CKD and AKI care were rated as above average or excellent in most high-income countries and as extremely poor or below average in most low-income countries.

Many challenges relating to health service oversight, funding, and infrastructure have been highlighted in this study. Despite knowledge of the importance of leadership in improving health outcomes, governance of kidney care differed greatly between countries. National oversight of patient care is most suited to containing health care costs and promoting equity and efficiency in resource allocation10, 11 and is particularly important in resource-poor settings because policies must clearly define patient eligibility for restricted therapy options, including dialysis. Similarly, robust legal frameworks are required, ideally at a national level, prior to establishment of transplantation programs. Lack of such frameworks leads to complex ethical issues, and in some cases may facilitate corrupt practices such as commercial organ trafficking and transplant tourism.12 Other issues included countries reporting the presence of more than 1 governing body for kidney care, which hindered the ability to exercise overall stewardship.6

Marked variations in health financing between Word Bank income groups and ISN regions were also identified. In contrast to the World Health Organization recommendations for good service delivery,6, 13 universal health coverage was not available in a significant proportion of countries, especially low-income countries and those in South Asia and Africa. Provision of universal health coverage is dependent on well-functioning health-financing systems. In high-income countries, prepayment schemes (e.g., taxes and insurance premiums) are frequently employed as a means to pool funds. However, similar systems in low-income countries would be unlikely to be successful due to differences in employment rates and financial security. Furthermore, the frequent need for patients in low-income countries to pay out of pocket at the point of service delivery effectively excluded many patients from accessing kidney care. This is evidenced by the fact that despite a high prevalence of end-stage renal disease (ESRD), relatively few patients receive renal replacement therapy in low-income countries. For example, <10% of Indian patients with ESRD receive renal replacement therapy, and as many as 70% of those starting dialysis die or stop treatment due to cost within the first 3 months.14 In a South African study, less than one-half of patients with ESRD were offered dialysis.15 Finally, a recently published systematic review of worldwide access to treatment for ESRD based on prevalence data from 123 countries estimated that between 47% and 73% of people with ESRD needing renal replacement therapy actually received it.16 This figure fell to 9% to 16% in Africa and 1% to 3% in middle and Eastern Africa.16

Of concern, a substantial proportion of countries did not publicly fund the early detection or prevention of progression of kidney disease in individuals at risk. Despite the financial burden of treating advanced kidney disease, few low-income countries publicly funded early kidney disease detection.16, 17 Screening for kidney disease in high-risk individuals18 is considered to be cost-effective19, 20, 21, 22, 23 and beneficial to public health.24 Therefore, consideration should be given to channeling resources into establishing and maintaining kidney disease screening programs in individuals at risk.25 Programs aimed at preventing progression of kidney disease should equally be a priority given the limited access to renal replacement therapy in low-income countries. Although data on the cost effectiveness of CKD prevention are not available, it would seem likely that prevention in the form of an integrated strategy targeting vascular disease and diabetes mellitus would be beneficial.

Development and maintenance of infrastructure is essential to support health system growth and development.26 For instance, even with appropriate health system oversight and financing, the absence of sufficient infrastructure will restrict growth of dialysis and transplantation. Unfortunately, the scope of this study did not examine each component of infrastructure quality, such as institutional capacity, physical infrastructure, telecommunication, and health information technology use.13, 26, 27 It is therefore not possible to detail specific shortcomings that affected health care infrastructure ratings. Detailed knowledge of these domains of infrastructure will be critical to targeting initiatives to improve the quality of infrastructure for AKI and CKD patient care.

This is the largest, most comprehensive and most up-to-date study of health systems oversight, financing, and infrastructure across countries and regions. Its strengths include high external validity (involving 122 countries with broad coverage across World Bank income groups and geographic regions), use of a rigorous survey instrument based on the widely applied World Health Organization health system building blocks,13 and involvement of a broad range of key regional and national stakeholders (including nephrologist leaders, health care policymakers, and consumer representative organizations). Follow-up was conducted with ISN regional leaders to resolve any data discrepancies. Lastly, triangulation of data with published literature and gray sources of information (government reports and other sources provided by survey respondents) was used for validation.

These strengths should be balanced against the study’s limitations, including response biases such as social desirability bias and demand characteristics. Such biases were mitigated by corroboration and validation of findings with regional leaders and published and gray literature at country levels. The nature of the survey also meant that the information acquired depended largely on the knowledge, expertise, and perceptions of respondents. Some aspects of the survey, such as the rating of infrastructural quality for kidney care, were subjective and therefore a matter of opinion. While the study’s assessment of the characteristics of good service delivery was based on the World Health Organization building blocks of health systems,13 some characteristics, such as continuity, person-centeredness, accountability, and efficiency, were not assessed. Finally, the study was not able to assess in detail the degree and nature of within-country variations in health system oversight, financing, and infrastructure.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated significant heterogeneity in health system oversight and financing across World Bank income groups and ISN regions. Deficiencies in the existing oversight and financing systems, as well as in the infrastructure supporting care for patients with kidney disease are likely to become progressively more significant in the context of increasing strain on financial resources resulting from the rising global prevalence of kidney disease. Governance systems should manage resources in ways that strengthen national health systems and promote universal health coverage. Several international programs have already been established in response to global inequities in access to treatment.28, 29 However, the success of such strategies may be undermined by inadequate governance systems and health financing. The findings of this study can provide important baseline information against which country progress can be benchmarked.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

The Global Kidney Health Atlas was a multinational, cross-sectional survey conducted by the ISN to evaluate the global capacity and readiness for kidney care. The survey was carried out with a specific focus on 130 countries with ISN affiliate societies, through the ISN’s 10 regional boards (Africa, Eastern and Central Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, Middle East, North America, North and East Asia, Oceania and Southeast Asia, Newly Independent States and Russia, South Asia, and Western Europe). The design, validation, distribution, and analysis of the survey have been previously reported.30, 31

As part of the survey, health system oversight, financing, and perceived adequacy of infrastructure were assessed. Survey respondents were asked to identify the organization responsible for oversight of health services caring for patients with kidney disease. These organizations included national bodies; provincial-, regional-, or state-level authorities; individual hospitals, trusts, or organizations; and NGOs. Respondents could also specify the absence of an organized oversight system.

Health system financing models were categorized as either public (i.e., government [national, provincial, state, regional, local]), or private (i.e., family or personal, corporate or for profit, charity, NGOs, and small business or entrepreneurial).32, 33 The following terms were used to further delineate funding types: publicly funded by government and free at point of delivery; publicly funded by government but with fees at point of delivery; a mixture of publicly funded (whether or not publicly funded component is free at point of delivery) and private systems; solely private and out of pocket; and multiple systems (i.e., programs provided by government, NGOs, and communities). For “mixed funding,” survey respondents were given the option to expand on this answer by adding an open-ended response to explain in more detail the formation of the health care system coverage.

The survey also asked whether universal health coverage was available to all of a country’s residents. Universal health coverage was defined as access by all residents to all aspects of health services, including promotive, preventive, rehabilitative, and palliative care, without additional costs to patients.6 Survey respondents had the opportunity to add an open-ended response to provide further explanation.30

As well as examining the financing structure of the health system, the survey also explored funding models for dialysis, kidney transplantation, nondialysis CKD, and AKI independently. It also addressed funding availability for early detection of CKD in high-risk individuals and prevention of CKD progression through risk factor control.

To assess the perceived adequacy of infrastructure supporting the care of patients with CKD and AKI, respondents were asked to rate the quality of the available services as extremely poor, poor or below average, fair or average, good or above average, and excellent.30

Countries were stratified by ISN regions7 and 2014 World Bank country classification as low-, lower middle-, upper middle-, and high-income nations.8

Disclosure

Publication of this article was supported by the International Society of Nephrology. The International Society of Nephrology holds all copyrights on the data obtained through this study. EB-F declared seeing private patients on a part-time basis. MBG declared receiving lecture fees from Amgen, B Braun, Leo Pharma, Novartis, Novo-Nordisk, Promopharm, Roche, Sanofi, Servier, Sophadial, and Sothema. DCH declared receiving lecture fees from Roche Myanmar and Otsuka. VJ declared receiving consulting fees from Baxter and Medtronic, and currently receiving grant support from the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India, Baxter, and GlaxoSmithKline. DWJ declared receiving consulting fees from AstraZeneca; lecture fees from Baxter Healthcare and Fresenius Medical Care; and support from Baxter Extramural and Clinical Evidence Council grants. KK-Z declared receiving past and future consulting and lecture fees from Abbott, Abbvie, Alexion, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Aveo, Chugai, DaVita, Fresenius, Genentech, Haymarket Media, Hospira, Kabi, Keryx, Novartis, Pfizer, Relypsa, Resverlogix, Sandoz, Sanofi, Shire, Vifor, and UpToDate; will receive future consulting and lecture fees from ZS-Pharma; currently receiving grant support from National Institutes of Health; and serving as an expert witness engagement for GranuFlo. RK declared receiving lecture fees from Baxter Healthcare. JP declared receiving consulting fees from Fresenius Medical Care, Baxter Healthcare, Otsuka, Boehringer Ingelheim; receiving lecture fees from Baxter Healthcare; and currently receiving grant support from Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Baxter Healthcare. All the other authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Marcello Tonelli and Valerie Luyckx for their contributions to the project and manuscript. We thank Sandrine Damster, Research Project Manager at the International Society of Nephrology (ISN), and Alberta Kidney Disease Network staff (Ghennete Houston, Sue Szigety, Sophanny Tiv) for their support with the organization and conduct of the survey and project management. We thank the ISN staff (Louise Fox and Luca Segantini) for their support. We thank the executive committee of the ISN, the ISN regional leadership, and the leaders of the ISN affiliate societies at regional and country levels for their support toward the success of this initiative.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2008. Health Systems Financing: Toolkit on Monitoring Health Systems Strengthening. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development . Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; Paris, France: 2015. Focus on Health Spending: OECD Health Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. WHO Global Health Expenditure Atlas. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. World Health Statistics 2014: Indicator Compendium. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Couser W.G., Remuzzi G., Mendis S., Tonelli M. The contribution of chronic kidney disease to the global burden of major noncommunicable diseases. Kidney Int. 2011;80:1258–1270. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2015. Health in 2015: From MDGs, Millennium Development Goals to SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. [Google Scholar]

- 7.International Society of Nephrology. ISN regions. 2017. Available at: https://www.theisn.org/about-isn/regions. Accessed August 23, 2017.

- 8.World Bank. World Bank country and lending groups: World Bank data help desk. Available at: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed August 23, 2017.

- 9.Boerma T., Eozenou P., Evans D. Monitoring progress towards universal health coverage at country and global levels. PLoS Med. 2014;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barsoum R.S. Haemodialysis: cost-conscious end-stage renal failure management. Nephrology. 1998;4:S96–S100. [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Health Partnership. Progress in the International Health Partnership and Related Initiatives, 2014 Performance Report. Geneva, Switzerland: International Health Partnership; 2014.

- 12.Gabr M. Organ transplantation in developing countries. World Health Forum. 1998;19:120–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2010. Monitoring the Building Blocks of Health Systems: A Handbook of Indicators and Their Measurement Strategies. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakhuja V., Sud K. End-stage renal disease in India and Pakistan: burden of disease and management issues. Kidney Int Suppl. 2003;83:S115–S118. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.63.s83.24.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moosa M.R., Kidd M. The dangers of rationing dialysis treatment: the dilemma facing a developing country. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1107–1114. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liyanage T., Ninomiya T., Jha V. Worldwide access to treatment for end-stage kidney disease: a systematic review. Lancet. 2015;385:1975–1982. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61601-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barsoum R.S., Khalil S.S., Arogundade F.A. Fifty years of dialysis in Africa: challenges and progress. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65:502–512. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inker L.A., Astor B.C., Fox C.H. KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63:713–735. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.01.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Komenda P., Ferguson T.W., Macdonald K. Cost-effectiveness of primary screening for CKD: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63:789–797. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kondo M., Yamagata K., Hoshi S.L. Cost-effectiveness of chronic kidney disease mass screening test in Japan. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2012;16:279–291. doi: 10.1007/s10157-011-0567-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farmer A.J., Stevens R., Hirst J. Optimal strategies for identifying kidney disease in diabetes: properties of screening tests, progression of renal dysfunction and impact of treatment—systematic review and modelling of progression and cost-effectiveness. Health Technol Assess. 2014;18:1–128. doi: 10.3310/hta18140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kondo M., Yamagata K., Hoshi S.L. Budget impact analysis of chronic kidney disease mass screening test in Japan. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2014;18:885–891. doi: 10.1007/s10157-014-0943-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manns B., Hemmelgarn B., Tonelli M. Population based screening for chronic kidney disease: cost effectiveness study. BMJ. 2010;341:c5869. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson D.W., Atai E., Chan M. KHA-CARI guideline: early chronic kidney disease: detection, prevention and management. Nephrology. 2013;18:340–350. doi: 10.1111/nep.12052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levey A.S., Atkins R., Coresh J. Chronic kidney disease as a global public health problem: approaches and initiatives—a position statement from Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes. Kidney Int. 2007;72:247–259. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Powles J, Comim F. Public health infrastructure and knowledge. In: Smith R, Beaglehole R, Woodward D, Drager N, eds. Global Public Goods for Health: Health Economic and Public Health Perspectives. 2003:159–176.

- 27.US Department of Health and Human Services . US Department of Health and Human Services; Bethesda, MD: 2010. National Healthcare Disparities Report. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marmot M., Friel S., Bell R. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008;372:1661–1669. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Provincial Health Services Authority. Towards Reducing Health Inequities: A Health System Approach to Chronic Disease Prevention. A Discussion Paper. British Columbia, Canada: Provincial Health Services Authority; Ottawa: Government of Canada; 2011.

- 30.Bello A.K., Johnson D.W., Feehally J. Global Kidney Health Atlas (GKHA): design and methods. Kidney Int Suppl. 2017;7:145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.kisu.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bello A.K., Levin A., Tonelli M. Assessment of global kidney health care status. JAMA. 2017;317:1864–1881. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blanchette C, Tolley E. Public and Private Sector Involvement in Health Care Systems: An International Comparison. Revised edition. Ottawa: Government of Canada; 2001.

- 33.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development . Revised edition. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; Paris, France: 2001. Public- and Private-Sector Involvement in Health-Care Systems: A Comparison of OECD Countries. [Google Scholar]