Abstract

Introduction Adrenomedullin 2 (ADM2) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) affect ovarian function, especially angiogenesis and follicular development. The actions of VEGF can be antagonized by its soluble receptors, soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1) and soluble VEGF receptor 2 (sVEGFR-2), as they decrease its free form. In the present study, we evaluated the relationship between follicular fluid (FF) levels of AMD2, VEGF and its soluble receptors, and ICSI outcomes.

Materials and Methods ICSI cycle outcomes were evaluated and FF levels of VEGF, sFlt-1, sVEGFR-2 and ADM2 were determined using ELISA kits.

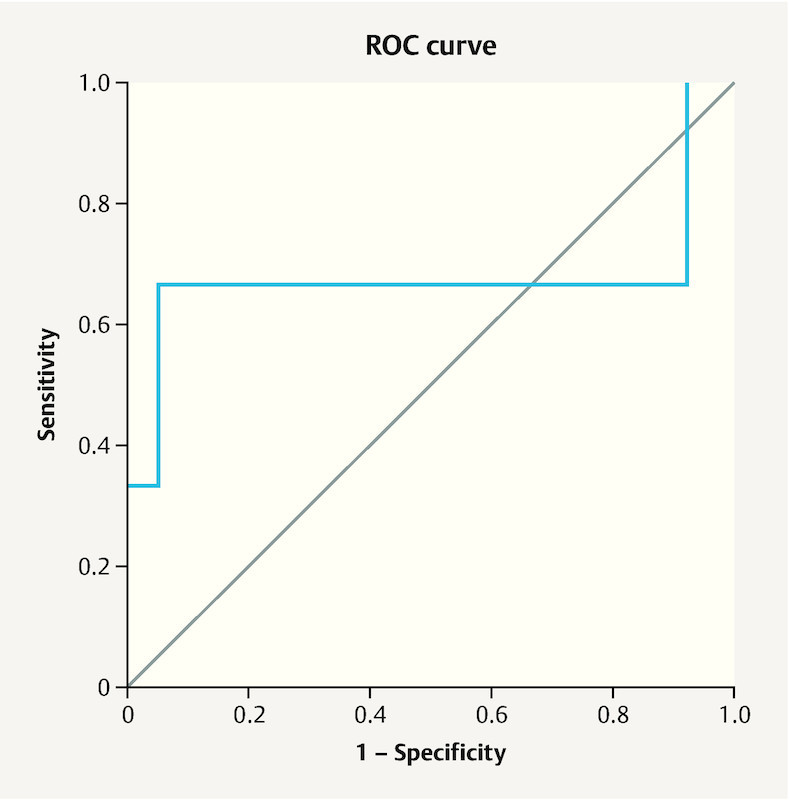

Results FF levels of ADM2, VEGF, and sVEGFR-2 were significantly higher in non-responders compared to other ovarian response groups (p < 0.05). There were significant correlations between ADM2, VEGF and sVEGFR-2 levels as well as VEGF/sFlt-1 and VEGF/sVEGFR-2 ratios (r = 0.586, 0.482, 0.260, and − 0.366, respectively). Based on the ROC curve, the cutoff value for ADM2 as a non-responder predictor was 348.55 (pg/ml) with a sensitivity of 67.7% and a specificity of 94.6%.

Conclusions For the first time we measured FF ADM2 levels to determine the relationship to VEGF and its soluble receptors. We suggest that ADM2 could be a potential predictive marker for non-responders. Although the exact function of ADM2 in ovarian angiogenesis is not yet understood, our study may shed light on the possible role of ADM2 in folliculogenesis and ovulation.

Key words: adrenomedullin 2, vascular endothelial growth factor, sFlt-1, follicular fluid, ICSI

Zusammenfassung

Einleitung Adrenomedullin 2 (ADM2) und der vaskuläre endotheliale Wachstumsfaktor (VEGF) wirken sich auf die ovarielle Funktion aus, insbesondere auf Angiogenese und Follikelentwicklung. Die Wirkung von VEGF kann durch seine löslichen Rezeptoren (den löslichen Fms-ähnlichen Tyrosinkinase-1 [sFlt-1] und den löslichen VEGF-Rezeptor 2 [sVEGFR-2]) antagonisiert werden, da diese Rezeptoren die freie Form von VEGF reduzieren. In dieser Studie haben wir den Zusammenhang zwischen den Follikelflüssigkeitsspiegeln von AMD2, VEGF und dessen löslichen Rezeptoren und dem Outcome nach ICSI untersucht.

Material und Methoden Das Outcome nach ICSI-Zyklen wurde evaluiert und die Follikelflüssigkeitsspiegel von VEGF, sFlt-1, sVEGFR-2 und ADM2 wurden mithilfe von ELISA Kits bestimmt.

Ergebnisse Die ADM2-, VEGF- und sVEGFR-2-Spiegel in der FF waren signifikant höher in der Gruppe von Frauen ohne ovarielle Reaktion verglichen mit anderen Gruppen mit ovarieller Reaktion (p < 0,05). Signifikante Korrelationen wurden zwischen den ADM2-, VEGF- und sVEGFR-2-Spiegeln sowie den VEGF/sFlt-1- und VEGF/sVEGFR-2-Quotienten festgestellt (r = 0,586, 0,482, 0,260 bzw. − 0,366). Gemäß der ROC-Kurve betrug der Cut-off-Wert für ADM2 als Prädiktor für keine ovarielle Reaktion 348,55 (pg/ml) mit einer Sensitivität von 67,7% und einer Spezifität von 94,6%.

Schlussfolgerungen Wir haben zum ersten Mal die Follikelflüssigkeitsspiegel von ADM2 gemessen und diese Werte mit den Werten von VEGF sowie dessen lösliche Rezeptoren in Beziehung gesetzt. Wir weisen darauf hin, dass ADM2 potenziell ein prädiktiver Marker für das Fehlen einer ovariellen Reaktion sein könnte. Obwohl die genaue Funktion von ADM2 bei der ovariellen Angiogenese noch nicht vollständig geklärt ist, konnte unsere Studie etwas Licht auf auf die möglichen Rollen von ADM2 bei der Follikulogenese und der Ovulation werfen.

Schlüsselwörter: Adrenomedullin 2, vaskulärer endothelialer Wachstumsfaktor, sFlt-1, Follikelflüssigkeit, ICSI

Introduction

Angiogenesis is a critical process in follicular development, with new blood vessels needed to provide nutrients, oxygen and paracrine as well as endocrine regulators 1 , 2 , 3 . With the formation of the antral cavity, the follicle is supported by a more extensive capillary network which provides nutrition for both theca and granulosa cells (GCs). The cells that are responsible for the production of follicular fluid (FF) contain angiogenic factors, most notably vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF, also known as VEGF-A) 4 , 5 .

VEGF binds to its receptors, VEGF receptor 1 (VEGFR-1, also called Flt-1) and VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR-2, also known as KDR) 6 , which have been detected in ovarian follicles, the corpus luteum and granulosa and theca cells 4 . Although VEGF has a higher affinity for Flt-1 than VEGFR-2, the tyrosine phosphorylation activity of VEGF/VEGFR-2 is stronger than the VEGFA/Flt-1 pathway 6 . VEGF is involved in the migration, proliferation and tube formation of endothelial cells 7 , and it has been demonstrated that loss of VEGF function in mice results in severe vascular abnormalities and embryonic lethality 8 . VEGF also facilitates the access of ovarian follicles to nutrients, gonadotropins and oxygen through the induction of ovarian angiogenesis 9 , improved vascular permeability and the consequent activation of primordial follicles; this may be important for the selection of the dominant follicle 10 . In addition, VEGF plays pivotal roles in oocyte maturation and ovulation and can thus improve fertilization rates 4 .

VEGF soluble receptors are produced by alternative splicing and/or shedding of membrane receptors. Soluble receptors do not have transmembrane or intracellular domains while the ligand-binding domain is retained 11 . Two soluble receptors of VEGF, soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1) and soluble VEGFR-2 (sVEGFR-2), antagonize the action of VEGF by reducing its free form, thereby decreasing angiogenesis 12 . It has been reported that the expression of sFlt-1 and sVEGFR-2 in dominant follicles is low compared with non-dominant follicles 12 . However, after dominant follicle selection, sVEGFR-2 expression increases while sFlt-1 expression decreases 12 .

Adrenomedullin 2 (ADM2, also known as intermedin) was recently discovered and belongs to the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) family 13 , 14 . ADM2 acts through the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) and calcitonin receptor-like receptor (CRLR) together with one of three receptor activity-modifying proteins (RAMP1, RAMP2, and RAMP3) 15 . ADM2 has many functions; it has anti-apoptotic and angiogenic effects, provides endothelial barrier protection, and contributes to anti-oxidative stress and anti-endoplasmic reticulum stress 16 . Its expression has been reported in various female reproductive tissues such as the ovaries and uterus 13 , 15 . Secretion of ADM, which is structurally and functionally close to ADM2, has been also reported for human GCs 17 . ADM2 is a crucial factor for maintaining the tertiary structure of the cumulus oocyte complex as well as regulating cumulus cell survival 18 . Moreover, it can induce vasodilation during pregnancy and mediates placentation in successful pregnancies 19 . It is well documented that ADM2 improves angiogenesis, mainly through the VEGF/VEGFR-2 pathway as it enhances the synthesis of VEGF and VEGFR-2 as well as the phosphorylation of VEGFR-2 in endothelial cells 20 . It has also been shown that administration of ADM2 antagonist into implantation sites reduces VEGF expression during early pregnancy 21 . However, the association between ADM2 and VEGF and its soluble receptors in FF has not been previously studied.

Given the potential roles of ADM2 and VEGF for ovarian function, especially angiogenesis and follicle development, the aim of the current study was 1) to measure the level of ADM2 in FF and evaluate its possible associations with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) cycle outcomes for the first time, and 2) to evaluate a possible association between ADM2 with VEGF and its soluble receptors in FF.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

A total of 90 women patients referred to Milad Infertility Center of Tabriz, Iran, were enrolled in this cross-sectional study. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects in accordance with the guidelines of the Ethical Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. The Committee approved the current study. The recruited infertile women were non-smokers aged from 20 – 40 years with fallopian tube obstruction, idiopathic infertility or male factor infertility (varicocele and oligospermia). Exclusion criteria were a history of PCOS, endometriosis, immune and inflammatory diseases, endocrine disorders, and male infertility with severe oligospermia (concentrations of less than 5 million sperm/mL) and azoospermia.

ICSI cycles

The long GnRH agonist–recombinant FSH (rFSH) protocol with the administration of exogenous gonadotropin (Gonal-F, Serono) was used for all patients. When a minimum of 2 – 3 follicles with diameters of 18 mm were detected, 10 000 IU intramuscular human chorionic gonadotropin (Choriomon, Lugano, Switzerland) was injected. Follicle aspiration was done 36 hours after hCG administration. Single FF aspiration without blood was carried out for all follicles. After separation of oocytes and centrifugation of the remaining fluid, the supernatant was kept frozen at − 80 °C until assay. The number of follicles and oocytes was assessed on the same day. The women were defined as non- (no. of oocytes = 0), poor- (no. of oocytes = 1 – 5), normo- (no. of oocytes = 6 – 10) and high-responders (no. of oocytes > 10) according to the number of retrieved oocytes 22 , 23 . All patients underwent ICSI, and the numbers of fertilized oocytes were calculated 48 hours later. Clinical pregnancy was established using transvaginal ultrasound to determine the presence of an intrauterine gestational sac. The implantation rate was defined as the quantity of visible sacs per number of transferred embryos. Fertilization rates were calculated by dividing the number of fertilized oocytes by the number of mature oocytes.

Follicular fluid parameters assays

FF VEGF, sFlt-1 and sVEGFR-2 levels were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (R & D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA). FF ADM2 levels were also measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (MyBioSource, Inc. San Diego, USA) according to the manufacturerʼs instructions. The sensitivities for ADM2, sVEGFR-2, VEGF and sFlt-1 were 7.8 pg/ml, 11.4 pg/ml, 9 pg/ml and 3.5 pg/ml, respectively. Intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation (CV) were respectively 5.1 and 6.2% for VEGF, 2.9 and 5.7% for sVEGFR-2, < 8 and < 10% for ADM2 and 2.6 – 3.8 and 7 – 9.8% for sFlt-1.

Since sFlt-1 and sVEGFR-2 are both VEGF soluble receptors and modulate free levels of VEGF, the VEGF/sFlt-1 and VEGF/sVEGFR-2 ratios were also calculated.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The normality of data was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. We used parametric and non-parametric tests for data with normal and abnormal distributions, respectively. Correlations between study variables were investigated by Pearson and Spearmanʼs correlation tests, depending on the distribution of data. Univariate and multivariate linear regression analysis was also used to evaluate relations between FF ADM2, sVEGFR-2, VEGF, VEGF/sVEGFR-2 and VEGF/sFlt-1 levels. p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant, and all analysis was done using SPSS 19.0 software.

Results

Clinical characteristics and factor levels in FF

Clinical characteristics and mean levels of VEGF, ADM2, sFlt-1 and sVEGFR are shown in Table 1 . The mean level of ADM2 in FF measured in this study was 62.2 ± 66.86 pg/ml. The measurements showed that patient age was significantly correlated with ADM2 (r = 0.268, p = 0.049) and VEGF/sFlt-1 (r = − 0.224, p = 0.047) levels and with the VEGF/sVEGFR-2 ratio (r = − 0.278, p = 0.018).

Table 1 Clinical characteristics and factor levels in follicular fluid in the study population (n = 90 women and ICSI cycles).

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| ADM2: adrenomedullin 2; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; sFlt-1: soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase-1; sVEGFR-2: soluble VEGF receptor 2 | |

| Number of follicles | 13.85 ± 12.28 |

| Age (years) | 31.28 ± 5.24 |

| Number of oocytes | 9.88 ± 6.48 |

| Total dose of FSH (IU) | 2095.60 ± 636.74 |

| Implantation rate | 0.05 ± 0.12 |

| Fertilization rate | 0.733 ± 0.225 |

| Number of embryos | 6.42 ± 4.1 |

| Clinical pregnancy rate | 13 (14.45%) |

| Follicular fluid factors | |

|

62.2 ± 66.86 |

|

1279 ± 577.72 |

|

408.67 ± 248.21 |

|

4.17 ± 1.82 |

Levels of follicular fluid factors according to ovarian response

The investigated factor levels were compared for non-, poor-, normo- and high-responders based on the number of retrieved oocytes ( Table 2 ). Our results showed that the levels of ADM2 in FF were significantly higher in non-responders compared to patients with poor, normo- and high ovarian response (p < 0.05). Moreover, the FF levels of VEGF, and sVEGFR-2 were significantly higher in non-responders than in poor-responders (p < 0.05). We found a significantly higher VEGF/sVEGFR-2 ratio in normo-responders compared with non-responders (p < 0.05). Moreover, sFlt-1 levels were lower in normo- and high-responder women compared with poor-responders (p < 0.05).

Table 2 Comparison of age, total dose of FSH, and follicular fluid factors in patients according to the number of retrieved oocytes.

| Parameters | Non-responders No. of oocytes = 0 (n = 14) |

Poor-responders No. of oocytes = 1 – 5 (n = 18) |

Normo-responders No. of oocytes = 6 – 10 (n = 30) |

High-responders No. of oocytes > 10 (n = 28) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSH: follicle-stimulating hormone; ADM2: adrenomedullin 2; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; sFlt-1: soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase-1; sVEGFR-2: soluble VEGF receptor 2 Significant differences (p < 0.05) compared with a non-responders, b poor-responders. | ||||

| Age (years) | 29 ± 8.64 | 34.07 ± 6.87 | 31.16 ± 4.44 | 30.28 ± 4.613 |

| Total dose of FSH (IU) | 1884.50 ± 1067.87 | 2270.31 ± 715.78 | 2055.06 ± 613.52 | 2040.35 ± 574.37 |

| ADM2 (pg/ml) | 282.60 ± 217.34 | 41.69 ± 9.68 a | 45.38 ± 10.75 a | 46.25 ± 7.65 a |

| VEGF (pg/ml) | 1452.25 ± 580.74 | 1066.6 ± 218.02 a | 1363.1 ± 700.76 | 1228.9 ± 421.06 |

| sFlt-1 (ng/ml) | 473.93 ± 426.19 | 536.87 ± 211.82 | 364.01 ± 258.04 b | 375.11 ± 230.02 b |

| sVEGFR-2 (ng/ml) | 8.38 ± 5.7 | 4.24 ± 1.82 a | 4.66 ± 3.13 | 5.38 ± 3.83 |

| VEGF/sFlt-1 | 2.98 ± 1.82 | 1.98 ± 0.94 | 3.38 ± 2.27 | 3.33 ± 2.01 |

| VEGF/sVEGFR-2 | 204.72 ± 68.51 | 265.29 ± 55.97 | 322.10 ± 188.13 a | 266.4 ± 67.21 |

Levels of follicular fluid factors according to pregnancy outcome

In order to find associations between the evaluated FF factors and pregnancy outcomes after ICSI, the factor levels in clinically pregnant and non-pregnant women were compared (data are presented in Table 3 ). The results showed no significant differences in the levels of ADM2, VEGF and sVEGFR-2 and no significant differences in VEGF/sFlt-1 and VEGF/sVEGFR-2 ratios between clinically pregnant and non-pregnant women (p = 0.399, 0.745, 0.470, 0.09 and 0.401, respectively).

Table 3 Comparison of studied follicular fluid factors according to clinical pregnancy results.

| Parameters | Pregnant (n = 13) | Non-pregnant (n = 77) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADM2: adrenomedullin 2; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; sFlt-1: soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase-1; sVEGFR-2: soluble VEGF receptor 2 | |||

| ADM2 (pg/ml) | 43.85 ± 5.46 | 65.08 ± 71.6 | 0.399 |

| VEGF (pg/ml) | 1419.4 ± 666.38 | 1256.6 ± 565.23 | 0.745 |

| sVEGFR-2 (ng/ml) | 4.01 ± 1.89 | 4.21 ± 1.83 | 0.470 |

| VEGF/sFlt-1 | 2.12 ± 1.25 | 3.05 ± 1.94 | 0.09 |

| VEGF/sVEGFR-2 | 329.87 ± 193.93 | 276.01 ± 116.27 | 0.401 |

Correlation of follicular fluid factors with ICSI cycle parameters

We investigated a possible correlation between measured parameters in FF and ICSI outcome. The data are presented in Table 4 . We found a positive correlation between VEGF/sFlt-1 and the number of retrieved oocytes (r = 0.269, p = 0.032). There was a positive and a negative correlation between fertilization rates and sVEGFR2 and the VEGF/sVEGFR2 ratio, respectively (r = − 0.243, p = 0.032 and r = 0.251, p = 0.027, respectively). There was no significant correlation between FF parameters and total FSH dose, number of follicles, and number of embryos.

Table 4 Correlation of follicular fluid factors with ICSI cycle parameters (n = 90 women and ICSI cycles).

| ADM2 (pg/ml) | VEGF (pg/ml) | sVEGFR2 (ng/ml) | VEGF/sFlt-1 | VEGF/sVEGFR2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P | R | P | R | p | r | p | R | p | |

| FSH: follicle-stimulating hormone; ADM2: adrenomedullin 2; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; sVEGFR-2, soluble VEGF receptor 2 Bold values are statistically significant at p < 0.05. | ||||||||||

| Total dose of FSH | 0.188 | 0.128 | 0.29 | 0.797 | 0.088 | 0.434 | 0.08 | 0.531 | − 0.085 | 0.445 |

| No. of follicles | − 0.003 | 0.982 | 0.133 | 0.318 | − 0.023 | 0.661 | 0.241 | 0.088 | 0.151 | 0.253 |

| No. of oocytes | 0.059 | 0.635 | − 0.006 | 0.960 | − 0.026 | 0.818 | 0.269 | 0.032 | 0.066 | 0.555 |

| Fertilization rate | 0.006 | 0.959 | − 0.076 | 0.511 | − 0.243 | 0.032 | − 0.220 | 0.092 | 0.251 | 0.027 |

| No. of embryos | 0.150 | 0.246 | 0.089 | 0.450 | 0.008 | 0.945 | 0.224 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.605 |

Correlations between levels of follicular fluid factors

Correlation analysis of FF factors indicated that ADM2 levels were positively correlated with VEGF and sVEGFR-2 levels as well as with the VEGF/sFlt-1 ratio (r = 0.586, p = 0.001; r = 0.482, p = 0.001 and r = 0.260, p = 0.039, respectively) ( Table 5 ). We found a negative correlation between ADM2 levels and the VEGF/sVEGFR-2 ratio (r = − 0.366, p = 0.002). sFlt-1 levels were negatively correlated with sVEGFR-2 levels (r = − 0.22, p = 0.049) and the VEGF/sFlt-1 ratio (r = − 0.86, p = 0.001). sVEGFR-2 levels were positively correlated with VEGF levels (r = 0.560, p = 0.001) and the VEGF/sFlt-1 ratio (r = 0.361, p = 0.004). The two evaluated ratios were negatively correlated to each other (r = − 0.263, p = 0.035, Table 5 ).

Table 5 Correlation between follicular fluid parameters of patients (n = 90 women and ICSI cycles).

| ADM2 (pg/ml) | VEGF (pg/ml) | sFlt-1 (ng/ml) | sVEGFR-2 (ng/ml) | VEGF/sFlt-1 | VEGF/sVEGFR-2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | R | p | R | P | r | p | r | P | r | p | |

| ADM2. adrenomedullin 2; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; sFlt-1, soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase-1; sVEGFR-2, soluble VEGF receptor 2 Bold values are statistically significant at p < 0.05. | ||||||||||||

| ADM2 (pg/ml) | – | – | 0.586 | 0.001 | 0.044 | 0.7 | 0.482 | 0.001 | 0.260 | 0.039 | − 0.366 | 0.002 |

| VEGF (pg/ml) | 0.586 | 0.001 | – | – | − 0.055 | 0.63 | 0.560 | 0.001 | 0.311 | 0.006 | 0.338 | 0.002 |

| sFlt-1 (ng/ml) | 0.044 | 0.7 | − 0.055 | 0.63 | – | – | − 0.22 | 0.049 | − 0.86 | 0.001 | 0.163 | 0.158 |

| sVEGFR-2 (ng/ml) | 0.482 | 0.001 | 0.560 | 0.001 | − 0.22 | 0.049 | – | – | 0.361 | 0.004 | − 0.778 | 0.001 |

| VEGF/sFlt-1 | 0.260 | 0.039 | 0.311 | 0.006 | − 0.86 | 0.001 | 0.361 | 0.004 | – | – | − 0.263 | 0.035 |

| VEGF/sVEGFR-2 | − 0.36 | 0.002 | 0.338 | 0.002 | 0.163 | 0.158 | − 0.778 | 0.001 | − 0.263 | 0.035 | – | – |

ADM2 cutoff in follicular fluid for non-responders

We used receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis to determine the predictive value of ADM2 in non-responder women. Based on the ROC curve, the cutoff value for ADM2 as a non-responder predictor was 348.55 (pg/ml) with a sensitivity and specificity of 67.7% (confidence interval, 67.21 – 68.25%) and 94.6% (confidence interval, 94.11 – 95.08%), respectively ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for adrenomedullin 2 (ADM2) levels in follicular fluid of non-responder women compared to other responder groups. Area under the curve (AUC) was 0.676 (p < 0.05). Using a cut-off value of 348.55 pg/ml, the sensitivity and specificity for ADM2 were 67.7 and 94.6%, respectively.

Discussion

A growing body of evidence shows the involvement of various cytokines, growth factors, miRNAs, enzymes and vitamins in the female reproductive system 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 . Previous studies have reported that the FF levels of VEGF increase significantly during follicular development and reach their peak just before ovulation 33 . We also found a positive correlation between VEGF/sFlt-1 and the number of retrieved oocytes. In accordance with our findings, Neulen et al. 22 reported a similar relation between FF VEGF/sFlt-1 ratio and the number of oocytes. VEGF mainly exerts its angiogenic function through VEGFR-2 and thereby supports dominant follicle selection through the reinforcement of angiogenesis 12 . Some studies have reported a negative relationship between VEGF and fertilization and pregnancy rates 34 , 35 . We also found a negative correlation between VEGF/sVEGFR2 ratio and the fertilization rate. Malamitsi-Puchner et al. 34 demonstrated an inverse association between fertilization rate and the expression of VEGF in the oocyte cumulus complex. However, other studies did not observe such associations 36 , 37 , 38 . Some studies have demonstrated a positive association between FF levels of VEGF and age and total FSH dose 38 . We did not find any correlation between FF VEGF and age or clinical pregnancy rates. However, there were significant negative correlations between patient age and FF VEGF/sFlt-1 and VEGF/sVEGFR-2 ratios. These results indicate the important role played by the soluble receptors in modulating VEGF activity. It should be noted that we and most previous studies measured total VEGF levels, although VEGF has multiple isoforms and some of them have anti-angiogenic properties 6 . A possible explanation for the different results in different studies could therefore be related to soluble VEGF receptors and the different isoforms of VEGF.

High and low expression of sVEGFR-2 and sFlt-1, respectively, has been reported in follicles at the post-dominant stage 39 . We also detected a negative correlation between FF sVEGFR-2 and sFlt-1 levels in our study. It could be hypothesized that in each phase of follicular development, one of the soluble receptors is dominant and responsible for modulating the bioactive form of VEGF.

In the present study, FF levels of VEGF were significantly higher in the non-responder group than in poor-responders. Hamuro et al. 40 have also reported increased levels of VEGF in non-responder women. In our study, we also found higher sVEGFR-2 levels in non-responders compared with poor-responders. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study indicating that FF sVEGFR-2 levels differ in women with different ovarian responses. It is well known that PlGF (placental growth factor) directs VEGF to VEGFR-2 by occupying Flt-1 and thereby reinforces angiogenesis 41 . We recently reported higher FF values for the PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio in high-responder women; therefore, increased FF values of PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio could be a marker for identifying high-responders who are at risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) 25 . On the other hand, anovulatory follicles have low Flt-1 expression 42 and probably impaired VEGF/VEGFR-2 pathway activation. Therefore, in anovulatory follicles, an angiogenic imbalance could lead to a secondary and compensatory elevation of VEGF as we found in our study.

In the current study, we demonstrated that FF ADM2 levels were positively correlated with age, and we also found higher FF levels of ADM2 in non-responder women compared to other responder groups. Other studies have shown that ADM2 can induce VEGF synthesis and also phosphorylation of VEGFR-2 in endothelial cells through activating its receptors 20 . We noted a positive correlation between ADM2 and sVEGFR-2 and VEGF and a negative correlation with VEGF/sVEGFR-2; this led us to speculate that ADM2 potentially upregulates sVEGFR-2 levels more strongly than VEGF and is partly responsible for VEGF regulation during oocyte maturation. However, previous studies on ADM, which has a functional and structural similarity to ADM2, found no correlation between ADM and ovarian function in either spontaneous or stimulated cycles 43 . Given the positive correlation of ADM2 with sVEGFR-2 as well as VEGF in our study and the low expression of Flt-1 in anovulatory follicles 42 , it could also be hypothesized that an elevation of ADM2 may be responsible for an angiogenic imbalance in non-responder women which exerts its effect through sVEGFR-2 and impairs activation of VEGFR-2 via VEGF; the existence of a balance between membrane and soluble forms of VEGFR-2 could be crucial for sufficient follicular angiogenesis and oocyte maturation. It should be noted that our group also recently proposed that in early pregnancy, ADM2 normally upregulates both VEGF and PLGF. This can induce angiogenesis and may also occur in the ovaries 26 .

In the present study, we found no significant difference in FF levels of evaluated factors between pregnant and non-pregnant women. As three high quality embryos were transferred in most cases, the lack of a significant difference between pregnant and non-pregnant women seems logical. However, in a study on FF ADM, a lower level of this factor was observed in follicles resulting in pregnancy compared to those that failed 44 .

Our results indicate that FF levels of ADM2 could be a potential marker for determining non-responder women. However, in order to evaluate the clinical utility of this factor, further studies are required to evaluate ADM2 serum levels before ovarian stimulation and assess the predictive value for non-responder women. An appropriate sample size, the evaluation of FF VEGF together with its soluble receptors and identifying ADM2 in FF as a possible regulator of VEGF signaling are the strengths of our study. However, further in vitro studies are needed to investigate possible interactions of ADM2 with VEGF signaling and the potential effects on oocyte maturation.

In conclusion, we found a significant association between ADM2 and FF levels of VEGF and its soluble receptors. We found higher FF levels of ADM2 in non-responder women and propose that ADM2 could serve as a potential marker for non-responders. Positive correlations of ADM2 with VEGF and sVEGFR-2 were obtained, which could be an important clue about the role of ADM2 in ovarian angiogenesis.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Milad Infertility Center for providing samples and clinical data. The study was financially supported by the Womenʼs Reproductive Health Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (grant number 5/4/1870). Part of the current study was presented at the ESHRE 2018 Congress.

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

These authors contributed equally and are considered co-first authors.

References

- 1.Robinson R S, Woad K J, Hammond A J. Angiogenesis and vascular function in the ovary. Reproduction. 2009;138:869–881. doi: 10.1530/REP-09-0283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babaei H, Roshangar L, Sakhaee E. Ultrastructural and morphometrical changes of mice ovaries following experimentally induced copper poisoning. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2012;14:558. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roshangar L, Rad J S, Afsordeh K. Maternal tamoxifen treatment alters oocyte differentiation in the neonatal mice: Inhibition of oocyte development and decreased folliculogenesis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36:224–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2009.01129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Araújo V R, Duarte A BG, Bruno J B. Importance of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in ovarian physiology of mammals. Zygote. 2013;21:295–304. doi: 10.1017/S0967199411000578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roshangar L, Rad J S, Nikpoo P. Effect of oxytocin injection on folliculogenesis, ovulation and endometrial growth in mice. Iran J Reprod Med. 2009;7:91–95. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McFee R M, Rozell T G, Cupp A S. The balance of proangiogenic and antiangiogenic VEGFA isoforms regulate follicle development. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;349:635–647. doi: 10.1007/s00441-012-1330-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patan S. Vasculogenesis and angiogenesis as mechanisms of vascular network formation, growth and remodeling. J Neurooncol. 2000;50:1–15. doi: 10.1023/a:1006493130855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carmeliet P, Ferreira V, Breier G. Abnormal blood vessel development and lethality in embryos lacking a single VEGF allele. Nature. 1996;380:435–439. doi: 10.1038/380435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaczmarek M M, Schams D, Ziecik A J. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor in ovarian physiology–an overview. Reprod Biol. 2005;5:111–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zimmermann R C, Xiao E, Husami N. Short-Term Administration of Antivascular Endothelial Growth Factor Antibody in the Late Follicular Phase Delays Follicular Development in the Rhesus Monkey 1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:768–772. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hornig C, Weich H A. Soluble VEGF receptors. Angiogenesis. 1999;3:33–39. doi: 10.1023/a:1009033017809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ortega Serrano P, Guzmán A, Hernández-Coronado C. Reduction in the mRNA expression of sVEGFR1 and sVEGFR2 is associated with the selection of dominant follicle in cows. Reprod Domest Anim. 2016;51:985–991. doi: 10.1111/rda.12777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takei Y, Inoue K, Ogoshi M. Identification of novel adrenomedullin in mammals: a potent cardiovascular and renal regulator. FEBS Lett. 2004;556:53–58. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01368-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hay D L, Garelja M L, Poyner D R. Update on the pharmacology of calcitonin/CGRP family of peptides: IUPHAR Review 25. Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175:3–17. doi: 10.1111/bph.14075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roh J, Chang C L, Bhalla A. Intermedin is a calcitonin/calcitonin gene-related peptide family peptide acting through the calcitonin receptor-like receptor/receptor activity-modifying protein receptor complexes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7264–7274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305332200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ni X, Zhang J, Tang C. Intermedin/adrenomedullin2: an autocrine/paracrine factor in vascular homeostasis and disease. Sci China Life Sci. 2014;57:781–789. doi: 10.1007/s11427-014-4701-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balasch J, Guimera M, Martinez-Pasarell O. Adrenomedullin and vascular endothelial growth factor production by follicular fluid macrophages and granulosa cells. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:808–814. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang C L, Wang H S, Soong Y K. Regulation of oocyte and cumulus cell interactions by intermedin/adrenomedullin 2. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:43193–43203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.297358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chauhan M, Ross G R, Yallampalli U. Adrenomedullin-2, a novel calcitonin/calcitonin-gene-related peptide family peptide, relaxes rat mesenteric artery: influence of pregnancy. Endocrinology. 2007;148:1727–1735. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albertin G, Sorato E, Oselladore B. Involvement of vascular endothelial growth factor signaling in CLR/RAMP1 and CLR/RAMP2-mediated pro-angiogenic effect of intermedin on human vascular endothelial cells. Int J Mol Med. 2010;26:289–294. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chauhan M, Elkins R, Balakrishnan M. Potential role of intermedin/adrenomedullin 2 in early embryonic development in rats. Regul Pept. 2011;170:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neulen J, Wenzel D, Hornig C. Poor responder-high responder: the importance of soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 in ovarian stimulation protocols. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:621–626. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.4.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frattarelli J L, Hill M J, McWilliams G D. A luteal estradiol protocol for expected poor-responders improves embryo number and quality. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:1118–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Latifi Z, Fattahi A, Ranjbaran A. Potential roles of metalloproteinases of endometrium-derived exosomes in embryo-maternal crosstalk during implantation. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:4530–4545. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nejabati H, Mota A, Farzadi L. Follicular fluid PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio and soluble receptor for advanced glycation end-products correlate with ovarian sensitivity index in women undergoing A.R.T. J Endocrinol Invest. 2017;40:207–215. doi: 10.1007/s40618-016-0550-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nejabati H R, Latifi Z, Ghasemnejad T. Placental growth factor (PlGF) as an angiogenic/inflammatory switcher: lesson from early pregnancy losses. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2017 doi: 10.1080/09513590.2017.1318375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rashidi M, Eisa-Khaje J, Farzadi L. Paraoxonase 3 activity and the ratio of antioxidant to peroxidation in the follicular fluid of infertile women. Int J Fertil Steril. 2014;8:51–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salmassi A, Fattahi A, Nouri M. Expression of mRNA and protein of IL-18 and its receptor in human follicular granulosa cells. J Endocrinol Invest. 2017;40:447–454. doi: 10.1007/s40618-016-0590-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Latifi Z, Fattahi A, Hamdi K. Wnt Signaling Pathway in Uterus of Normal and Seminal Vesicle Excised Mated Mice during Pre-implantation Window. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2018;78:412–422. doi: 10.1055/a-0589-1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mihanfar A, Fattahi A, Nejabati H R. MicroRNA-mediated drug resistance in ovarian cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2017 doi: 10.1002/jcp.26060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shahnazi M, Nouri M, Mohaddes G. Prostaglandin E pathway in uterine tissue during window of preimplantation in female mice mated with intact and seminal vesicle-excised male. Reprod Sci. 2018;25:550–558. doi: 10.1177/1933719117718272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Latifi Z, Nejabati H, Ranjbaran A. Association of follicular fluid levels of adrenomedullin 2, vascular endothelial growth factor and its soluble receptors with ICSI outcome. Hum Reprod. 2018;33:305–306. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Einspanier R, Schönfelder M, Müller K. Expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors and effects of VEGF during in vitro maturation of bovine cumulus-oocyte complexes (COC) Mol Reprod Dev. 2002;62:29–36. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malamitsi-Puchner A, Sarandakou A, Baka S G. Concentrations of angiogenic factors in follicular fluid and oocyte-cumulus complex culture medium from women undergoing in vitro fertilization: association with oocyte maturity and fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:98–101. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)01854-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ocal P, Aydin S, Cepni I. Follicular fluid concentrations of vascular endothelial growth factor, inhibin A and inhibin B in IVF cycles: are they markers for ovarian response and pregnancy outcome? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;115:194–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friedman C I, Seifer D B, Kennard E A. Elevated level of follicular fluid vascular endothelial growth factor is a marker of diminished pregnancy potential. Fertil Steril. 1998;70:836–839. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00301-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim K H, Oh D S, Jeong J H. Follicular blood flow is a better predictor of the outcome of in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer than follicular fluid vascular endothelial growth factor and nitric oxide concentrations. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:586–592. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.02.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manau D, Balasch J, Jiménez W. Follicular fluid concentrations of adrenomedullin, vascular endothelial growth factor and nitric oxide in IVF cycles: relationship to ovarian response. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:1295–1299. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.6.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Macias V, Pinzón C, Fierro F. Identification of Soluble Forms of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor receptors, sVEGFR-1 and sVEGFR-2, in Bovine Dominant Follicles. Reprod Domest Anim. 2012;47:e39–e42. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2011.01919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamuro A, Tachibana D, Misugi T. Serum Biopterin and Neopterin Levels as Predictors of Empty Follicles. Jpn Clin Med. 2015;6:29–34. doi: 10.4137/JCM.S32018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carmeliet P, Moons L, Luttun A. Synergism between vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor contributes to angiogenesis and plasma extravasation in pathological conditions. Nat Med. 2001;7:575–583. doi: 10.1038/87904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ellenberger C, Müller K, Schoon H A. Histological and immunohistochemical characterization of equine anovulatory haemorrhagic follicles (AHFs) Reprod Domest Anim. 2009;44:395–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2008.01085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marinoni E, Di Iorio R, Villaccio B. Follicular fluid adrenomedullin concentrations in spontaneous and stimulated cycles: relationship to ovarian function and endothelin-1 and nitric oxide. Regul Pept. 2002;107:125–128. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(02)00093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marinoni E, Feliciani E, Muzzonigro F. Intrafollicular concentration of adrenomedullin is associated with IVF outcome. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2010;26:435–439. doi: 10.3109/09513591003632076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]