Abstract

Older adults suffer from weakened and delayed bone healing due to age-related alterations in bone cells and in the immune system. Given the interaction between the immune system and skeletal cells, therapies that address deficiencies in both the skeletal and the immune system are required to effectively treat bone injuries of older patients. The sequence of macrophage activation observed in healthy tissue repair involves a transition from a pro-inflammatory state followed by a pro-reparative state. In older patients, inflammation is slower to resolve and impedes healing. The goal of this study was to design a novel drug delivery system for temporal guidance of the polarization of macrophages using bone grafting materials. A biomimetic calcium phosphate coating (bCaP) physically and temporally separated the pro-inflammatory stimulus interferon-gamma (IFNγ) from the pro-reparative stimulus simvastatin (SIMV). Effective doses were identified using a human monocyte line (THP-1) and testing culminated with bone marrow macrophages obtained from old mice. Sequential M1-to-M2 activation was achieved with both cell types. These results suggest that this novel immunomodulatory drug delivery system holds potential for controlling macrophage activation in bones of older patients.

Keywords: drug delivery, macrophages, calcium phosphate, simvastatin, bone repair, aging

1. Introduction

Macrophages are present in nearly all tissues and are critical for tissue remodeling, homeostasis, and regeneration. Most tissues contain a population of resident macrophages that are able to dynamically adapt to changes in their microenvironment in order to orchestrate critical tissue-specific functions. After a bone injury, macrophages are among the first cells recruited from the bone marrow and peripheral blood to the site of injury, where they coexist with resident macrophages within the bone injury site (1). Uncommitted macrophages (M0) are originate from monocytes that infiltrate rapidly to the site of injury (2) and lead to the secretion of inflammatory factors such as monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1). One of the major roles of MCP-1 is the recruitment of mesenchymal progenitor cells in the early phase of fracture healing (3). Depending on the stage of healing at the injured site, uncommitted macrophages (M0) become polarized toward an appropriate activation pathway that helps to regulate all phases of the healing process. First, macrophages exhibit a pro-inflammatory phenotype (commonly referred to as M1) (4). M1 macrophages are critical for the initiation of angiogenesis and osteogenesis (5). At later stages of healing, M1 macrophages transition to a pro-reparative phenotype (commonly referred to as M2) to guide the repair process to completion (5). It is now known that M2 macrophages can be further subdivided into a series of distinct phenotypes, each with diverse functions ranging from tissue deposition to tissue remodeling (6). Injuries with poor healing outcomes are associated with a stalled M1-to-M2 transition (7, 8). Given the sequential and synergistic roles of M1 and M2 macrophages in the healing process, it has been proposed that biomaterial strategies that sequentially promote M1 followed by M2 activation will enhance healing compared to promotion of either phenotype alone or concurrent promotion of both types (5, 9, 10).

Many patients requiring bone repair treatments are older with chronic low levels of inflammation (11). A few studies have examined the behavior of macrophages obtained from older mice and humans and seen an age-related impairment in macrophage polarization, cytokine production, phagocytic ability and have linked this to the impaired bone healing seen in older patients (12–14). Age-related alterations in macrophage function and response to stimuli have been reported in old mouse bone marrow derived macrophages (15–19), as well as in human macrophages derived from peripheral blood monocytes taken from older patients over 65 years of age (20). In general, macrophages from older humans and animals tend to secrete higher baseline levels of pro-inflammatory (M1) cytokines (e.g. IL6 and TNFα), and respond more slowly to inflammatory stimuli as compared to macrophages from young humans and animals (21). Decreased production of pro-reparative (M2) cytokines has been observed in macrophages from old mice (13). There is also an increase in macrophage accumulation in dermal, adipose, thyroid and liver tissue in older humans and animals (14, 22–24). In mice, it was demonstrated that transplanting bone marrow that contains the hematopoetic precursors for macrophages from 4-week-old young mice into 12-month-old adult mice improved fracture healing (25). In addition, impaired cutaneous wound healing in aged mice was reversed when macrophages from young mice were transferred to aged mice (26). Thus, a biomaterials delivery system with appropriately timed delivery of stimuli that can restore youthful macrophage polarization of endogenous macrophages could be a promising approach to enhance bone and tissue healing in the older population, but must consider the alterations to the macrophages present in the elderly tissue environment.

Several strategies for local delivery of molecules to modulate macrophage phenotype in young mice have been developed to accelerate tissue repair. M1 macrophages are usually activated by interferon gamma (IFNγ) and/or lipopolysaccharide (LPS), while M2 macrophages are activated by interleukins IL-4, IL-13 or IL-10 (27, 28), although it is likely that polarization stimuli in vivo are more complex and multifaceted. In a murine subcutaneous implantation model, the release of IFNγ enhanced vascularization relative to controls, but the dual delivery with IL-4 had no effect (9). The lack of effect was attributed to the overlapping IFNγ and IL4 release profiles at the early phases, which caused simultaneous, not consecutive, M1 and M2 activation. Indeed, too early of an increase of M2 macrophages can be detrimental as shown by impaired wound healing from administration of M2 macrophages at early times after injury (29), although this finding may be context-dependent (14). Thus, a major goal of the present study was to design a biomaterial drug delivery system that sequentially delivers M1- and M2-promoting stimuli in distinct phases and to test the strategy in macrophages from old mice.

Biomimetic calcium phosphate deposition via simulated body fluids (SBF) has been shown to be an effective method of coating many different types of biomaterials (30–33). The structure of biomimetic calcium phosphate (bCaP) closely matches the structure of natural bone mineral and bCaP enhances cell adhesion, proliferation, implant fixation and bone regeneration (34–36). In addition, sustained release of proteins or growth factors within the therapeutic range can be achieved by incorporating therapeutic agents into the coating (37–41). A gradual long-term release of simvastatin was also achieved by the incorporation of the drug in bCaP coating (42–44).

In the present study, the applicability of a biomimetic calcium phosphate coating to serve as a highly localized delivery system to guide macrophage phenotype transitions was tested. The effect of in vitro sequential delivery of M1-stimulating IFNγ followed by the anti-inflammatory, M2-promoting simvastatin (SIMV) (45–52) by bCaP was studied. Both human macrophages (THP-1 cell line), as well as primary mouse-bone marrow derived macrophages were tested. Macrophages were obtained from very old mice, 25–26 months old, that correlates to >85 human years (53). The overall goal of the study was to test the hypothesis that the sequential delivery of IFNγ followed by SIMV from bCaP can sequentially polarize both young and aged macrophages, in vitro, from M1 to M2.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Application of bCaP coating with or without macrophage stimulating molecules

Simvastatin, (PHR1438, Sigma Aldrich), the M2-promoting molecule, was adsorbed directly on the top surface of ultra violet light-sterilized, 22 mm polystyrene disks (NUNC, Rochester, NY), by placing 10 ul of ethanol containing 0, 2 or 10 μg SIMV on the top surface of the disk and allowing it to dry for 10 min. A tab was created on the edge of the disk allowing later identification of the top surface so that IFNγ and cells could be seeded on the side with the SIMV. A coating of bCaP was deposited to cover the SIMV or vehicle following a previously reported method (54). Briefly, the disks were immersed in a 5× concentrated simulated body fluid solution in a two-step process leading to a crystalline, bone-like apatite coating on both sides of the disk (55–57). After bCaP application, 0, 250 or 500 ng of the M1 stimulating molecule IFNγ (Cat#300–02, Peprotech Inc, NJ) in 0.5 ml PBS was adsorbed for one-hour on the same side of the bCaP coated disks with SIMV and then rinsed with PBS. Disks were placed in 12 well non-treated tissue culture plastic cell culture dishes (Corning, USA, Cat# 351143) for the studies with the drug loaded side facing upwards. Cells were also cultured directly on non-treated polystyrene as a control for comparison to bCaP coated disks.

In the studies that determined the kinetics of macrophage access to a factor embedded below the bCaP layer, a cytotoxic dose of antimycin A (AntiA, Cat# A8674, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was pipetted on to the disks without any coating, allowed to adsorb and then covered with a layer of bCaP as described above. The dose of 213 μg Anti A/disk was applied by placing10 μl of a 40 mM solution in ethanol on the side of the TCPsb disks to be cell-seeded, allowed to dry for 10 minutes and then rinsed three times with saline prior to bCaP coating. No SIMV or IFNγ were used in the experiments with AntiA.

To determine the dose of IFNγ bound to the bCaP surface, a binding solution of 250 ng of IFNγ in 0.5 ml PBS was placed on one side of bCaP coated disks for one hour and then collected for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay ELISA (PeproTech, Inc., New Jersey, Cat# 900-TM27). The disk was then rinsed twice with PBS with the first rinse removed immediately and the second one after 30 min. The difference between initial binding solution concentration and the concentration after 1 hr adsorption was used to determine the IFNγ bound on the disks. 100% binding efficiency of SIMV and Anti A was assumed based on their poor solubility and inability to detect the molecules by standard UV-VIS methods.

2.2. Release studies

IFNγ release:

To determine the release kinetic of IFNγ from the bCaP surface, bCaP coated disks were covered with 200ng of IFNg in PBS for one hour. bCaP-IFNγ disks were then incubated in 1 ml of PBS, the PBS solution was then collected at day 1 through 6 for measurement by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay ELISA (PeproTech, Inc., New Jersey, Cat# 900-TM27). PBS was replenished with fresh 1 ml at each time point. The amount of IFNγ released from the bCaP coated disks was below the detection level.

SIMV release:

10 ug SIMV was absorbed on the top surfaces of the disks then covered with bCaP coating as described above. To determine the release kinetics of SIMV from the bCaP, bCaP-SIMV coated disks were incubated in 1 ml PBS in cell culture plates with the SIMV coated surface up and the PBS solution was then collected at 4 hrs, and day 1 through 6 for SIMV measurements using a UV-VIS method at 238 nm in a quartz cuvette. PBS was replenished with fresh 1 ml at each time point.

2.3. Cell culture

Monocyte cell line:

The monocyte cell line THP-1 (ATCC® TIB-202™) derived from human peripheral blood from a one year old male was used to obtain macrophages to determine effective dose ranges. THP-1 cells were expanded in ultra-low attachment flasks (Corning, USA, cat# CLS3814) in RPMI medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate. THP-1 at 0.6 million cells/ml were differentiated to macrophages through incubation in 100 mM phorbol-12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (Sigma, USA, P8139) for 24 hrs. Macrophages were then gently scraped off the ultra-low attachment culture flask and seeded at 1 ×106 cell/ml on bCaP coated disks with or without the drugs/cytokines that had been incubated for 30 min in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) prior to cell culture. In the SIMV dose determination studies, cells were cultured with 100ng/ml of both LPS and IFNγ in the medium to provide the M1 stimulation, and then refreshed on day 3 with drug free medium to evaluate the M2 effect of simvastatin.

Mouse Bone Marrow Derived Macrophages (BMDMs):

The preparation of BMDMs from adult and old mice followed a previously described method (58). Briefly, four male C57BL/6 mice that were either 6 months (adult) or 25 months old (old) were euthanized using CO2 inhalation according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care Use Committee of University of Connecticut Health Center following recommendations of the Panel on Euthanasia of the American Veterinary Medical Association. Bone marrow of the dissected femurs and tibias were flushed with 5 mL DMEM (Gibco™ Invitrogen, CA, USA). The marrow was centrifuged for 5 mins and washed twice with medium and then cultured for five days in 100 mm non-treated tissue culture dish with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 20 ng/mL monocyte colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) (PeproTech, Inc, NJ, USA, Cat# 300–25) and 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. The cells were then gently scraped off the dish and re-suspended with media and plated at 0.5 ×106 cell/ml on bCaP coated disks with or without the drugs/cytokines that had been incubated for 30 min in RPMI medium prior to cell culture. Time points for analysis were restricted to day 1 and day 6 due to the difficulty of obtaining more than four of the very old mice at a time. Studies were repeated twice.

2.4. Characterization of macrophage phenotype transitions

Macrophage phenotype characterization:

The expression of a panel of genes previously identified to be suitable for consistently discriminating M1 and M2 macrophage phenotypes of both THP1 and murine macrophages were evaluated in these studies (42). Given the previous time scale of macrophage phenotype transitions in response to biomaterials observed in our earlier studies (9), the time points of 1, 3 and 6 days were selected for analysis of macrophage phenotype on the bCaP coated disks. Primer sequences can be found in Table 1. The cells were harvested for gene analysis using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, CA, USA). RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using EcoDry Premix (Oligo dT) (Cat# 639543, Clontech) and thermocycler (BIO-RAD Laboratories Inc., CA, USA) followed by Quantitative Polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) using iTaq™ universal SYBR® Green supermix kit (BIO-RAD Laboratories Inc., CA, USA) on a MyiQTM instrument. Values were normalized to GAPDH using 2−Δct method, where ∆CT is the result of subtracting [CT gene − CT GAPDH] of control or experimental group.

Table 1.

PCR primer sequence

| Human peripheral blood THP-1: Housekeeping gene | ||

| Gene | Forward Sequence | Reverse Sequence |

| GAPDH | AAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTCAAC | GGGGTCATTGATGGCAACAATA |

| Human peripheral blood THP-1: M1 Markers | ||

| Gene | Forward Sequence | Reverse Sequence |

| CCL1 | GATGCTGAACAGTGACAAATC | TCAGGAACAGCCACCAGTG |

| CXCL11 | GACGCTGTCTTTGCATAGGC | GGATTTAGGCATCGTTGTCCTTT |

| CXCL10 | ACACTAGCCCCACGTTTTCT | GAGAGGTACTCCTTGAATGCCA |

| Human peripheral blood THP-1: M2 Markers | ||

| Gene | Forward Sequence | Reverse Sequence |

| GAPDH | CAGTGCCAGCCTCGTCCCGTAGA | CTGCAAATGGCAGCCCTGGTGAC |

| CD163 | TTTGTCAACTTGAGTCCCTTCAC | TCCCGCTACACTTGTTTTCAC |

| CCL17 | CGGGACTACCTGGGACCTC | CCTCACTGTGGCTCTTCTTCG |

| Mouse : Housekeeping gene | ||

| Gene | Forward Sequence | Reverse Sequence |

| GAPDH | CAGTGCCAGCCTCGTCCCGTAGA | CTGCAAATGGCAGCCCTGGTGAC |

| Mouse: M1 Markers | ||

| Gene | Forward Sequence | Reverse Sequence |

| Cxcl11 | AGTAACGGCTGCGACAAAGT | GCACCTTTGTCGTTTATGAGC |

| Nos2 | AAACCCCTTGTGCTGTTCTC | ATACTGTGGACGGGTCGATG |

| Il1β | TTCAGGCAGGCAGTATCACTC | GAAGGTCCACGGGAAAGACAC |

| Mouse: M2 Markers | ||

| Gene | Forward Sequence | Reverse Sequence |

| Arg1 | GCAGAGGTCCAGAAGAATGG | AGCATCCACCCAAATGACAC |

| Ccl17 | TGCTTCTGGGGACTTTTCTG | CATCCCTGGAACACTCCACT |

Cytokine Assay:

TNFα, IL6, IL1β, and IL10 were measured in supernatants of THP-1 macrophages cultured on bCaP coatings with or without 250 ng of IFNγ and with 10 μg SIMV embedded within the bCaP coating using a Human Inflammatory Cytokine Bead Array per the manufacturer’s (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) protocol. Data were collected on a MACSQuant Analyzer (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany).

Kinetics of macrophage access to the factor below bCaP coating:

LIVE® staining (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), as per the manufacturer’s protocol, was used to evaluate THP-1 macrophage access over time to the cytotoxic AntiA adsorbed under the bCaP coating. Cells cultured on the disks were imaged at 100X magnification using an inverted microscope (TE300, Nikon) equipped with a camera (Diagnostic Instruments), and imaging software (Spot Insight, Nikon). THP-1 cell density was quantified as average percent fluorescent area via ImageJ software (U. S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, US) as follows: the images were converted to grayscale; threshold to binary images and the percent area of LIVE stain were estimated using Image-J software (U. S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA). Percent cell viability was calculated by comparing the average percent fluorescent area of the AntiA group to its AntiA-free control. ImageJ analysis was performed for 3 images per well with 3 wells per each experimental time point.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using using GraphPad Prism by unpaired t-tests if there were only two groups or by one-way ANOVA (p<0.05) with Tukey post-test for experiments with 3 or more groups.

3. Results

3.1. Localized, temporally controlled drug delivery from bCaP coatings

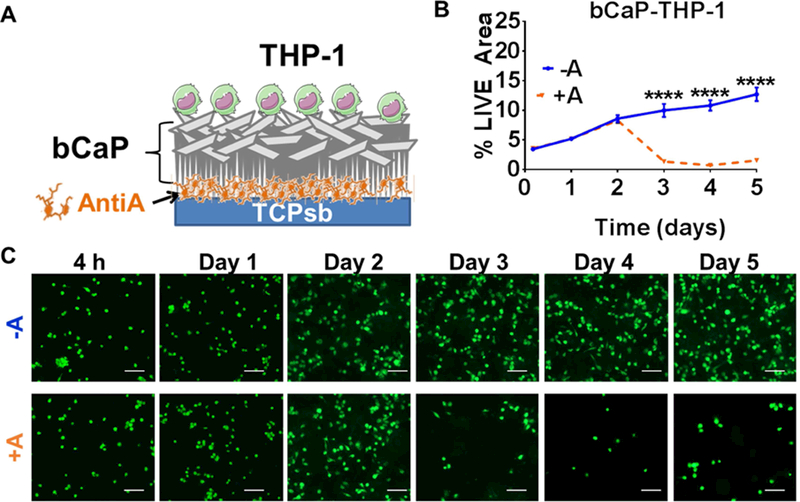

To understand the timing of macrophage access to drug embedded below the bCaP barrier layer, human THP-1-derived macrophages were cultured on bCaP or bCaP-AntiA-coated disks and cell viability was quantified. While the macrophages initially proliferated in both groups, by day 3 the macrophages began to die on scaffolds coated with bCaP-AntiA, indicating that the cells accessed the cytotoxic drug by that time point (Figure 1). With regards to the dose of IFNγ adsorbed on the outer surface of the bCaP, ELISA testing revealed that 96% of the IFNγ placed on the bCaP bound to bCaP coating. The IFNγ concentration was below the limits of detection in the 30 min rinse solution by ELISA, but was detected in the day 1 release sample (40 pg/ml). The concentrations of IFNγ in each of the remaining time point samples was ~7 pg/ml.

Figure 1:

Evaluation of the kinetics of THP-1 macrophage access to the cytotoxic AntiA molecule below the biomimetic calcium phosphate (bCaP) barrier coating. (A) Schematic representation of the bCaP coating and AntiA location. (B) Quantified percent LIVE® stained area of THP-1 cells on bCaP coating (**** P < 0.001). (C) Fluorescent LIVE® stained images of cells cultured on bCaP alone (-A) as compared to cells cultured on bCaP-AntiA (+A) at over time in culture. Scale bar = 100 μm.

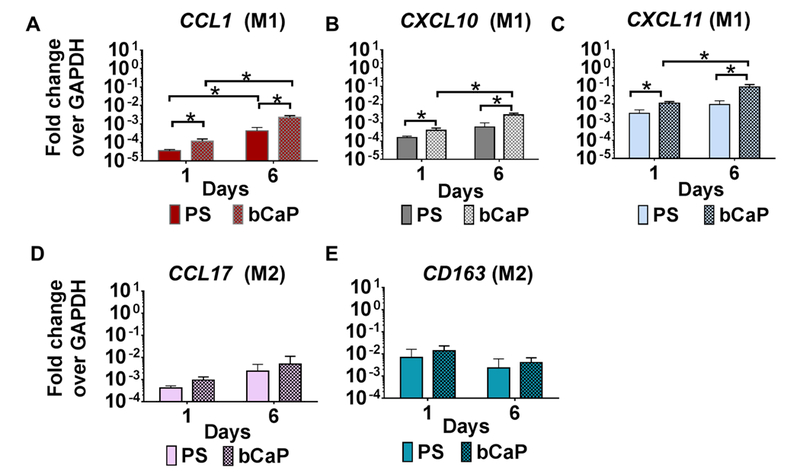

3.2. Response of macrophages to bCaP coatings

As a step towards understanding the effect of the bCaP coating itself without additional factors to modulate macrophage behavior, the response of macrophages to this material was compared to a control, non-tissue culture-treated polystyrene (PS). Culture of human THP1 monocyte-derived macrophages on the bCaP coating resulted in upregulation of all three M1 markers measured at 1 and 6 days of culture as compared to PS (Figure 2 A–C). The M2 markers were not affected by culture on bCaP compared to PS (Figure 2 D and E).

Figure 2:

Gene expression of human THP-1 macrophages cultured on bCaP as compared to non-tissue culture-treated polystyrene (PS) on day 1 and day 6 of culture. (A-C) M1 macrophage markers. (D and E) M2 macrophage markers. qRT-PCR data presented as fold change over the housekeeping gene GAPDH. * P < 0.05.

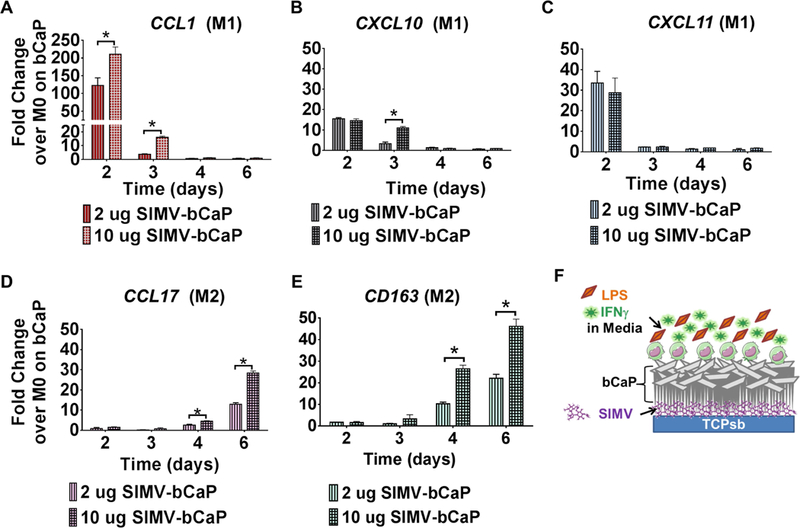

3.3. SIMV dose optimization

To determine the dose of SIMV delivered from bCaP that could influence M2 polarization, human THP1-derived macrophages were cultured on bCaP-coated disks containing 2 or 10 μg of SIMV in the presence of M1-polarizing stimuli, IFNγ and LPS, contained in culture medium for the first three days. Interestingly, increasing the dose of SIMV from 2 to 10 μg caused an increase in expression of the M1 marker CCL1 at days 2 and 3 and in CXCL10 at day 3. By day 4, however, SIMV caused the expression of all three M1 markers to decrease, concomitantly with an increase in expression of the M2 markers CCL17 and CD163 in a dose-responsive way (Figure 3 D and E). Spectrophotometer data of the release study samples showed that SIMV released from bCaP was below the detection limit in the first three days; however, SIMV was detectable starting at day 3 of incubation at ~ 0.20 ug/ml at each day until day 6 when it reached a maximum of 0.62 ± 0.05 ug/ml.

Figure 3:

Simvastatin dose response study. Gene expression of human THP-1 macrophages cultured on bCaP with either 2 or 10 μg SIMV beneath the bCaP with LPS and IFNγ in the media for the first three days. (A-C) M1 macrophage markers and (D and E) M2 macrophage markers. (F) Schematic representation of the experimental configuration. qRT-PCR data presented as fold change over the housekeeping GAPDH and normalized to M0 macrophages cultured on bCaP without drug. * P < 0.05.

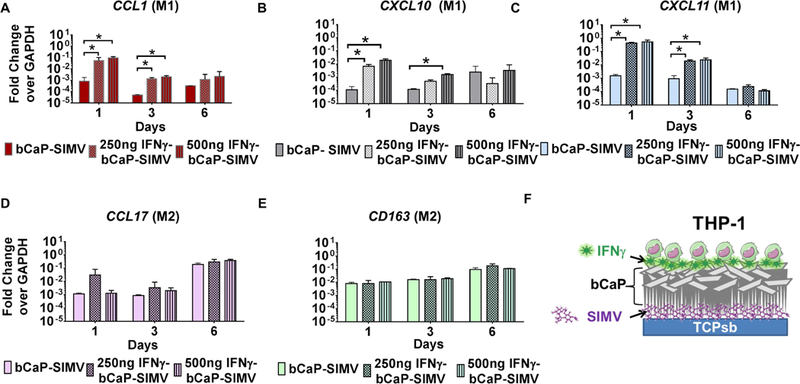

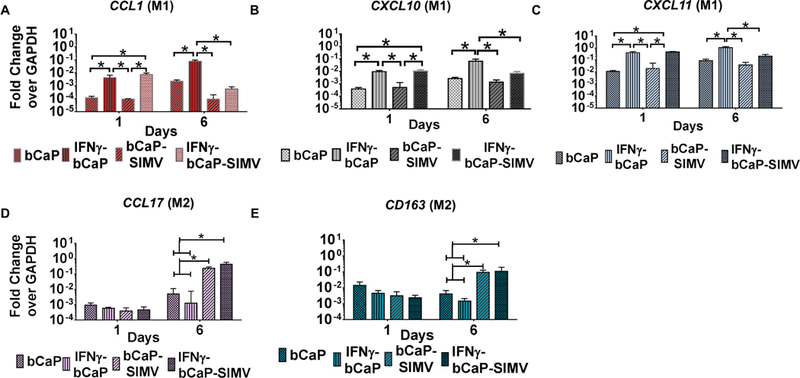

3.4. Sequential delivery of IFNγ followed by SIMV

To determine if adsorbed IFNγ delivered from bCaP could promote early polarization to the M1 phenotype prior to SIMV-mediated M2 polarization, in the absence of inflammatory stimuli in the media, macrophages were cultured on bCaP coatings adsorbed with 0, 250 ng and 500 ng of IFNγ, with 10 μg SIMV embedded within the bCaP coating. Both doses of IFNγ polarized THP-1-derived macrophages to the M1 phenotype at the early time point (1 day), as measured by increased expression of CCL1, CXCL10 and CXCL11, compared to the bCaP-SIMV control (Figure 4 A–C). Upregulation of CCL1 and CXCL11 was also maintained on day 3. By day 6, the expression of all three M1 markers had returned to baseline levels of macrophages cultured on bCaP-SIMV without IFNγ. The expression of the M2 markers increased in all bCaP loaded with SIMV, but only at the day 6 time point (Figure 4 D and E). The shift from M1, stimulated by immediate IFNγ delivery from bCaP, to M2 phenotype, stimulated by delayed SIMV delivery from bCaP, confirmed the ability of bCaP to serve as barrier layer between the two factors delivered to macrophages with no overlap between the molecules to be delivered.

Figure 4:

IFNγ dose response study in combination with 10 μg SIMV. Gene expression of human THP-1 macrophages cultured on bCaP with IFNγ on the exterior and SIMV below the bCaP barrier layer. (A-C) M1 macrophage markers. (D and E) M2 macrophage markers. (F) Schematic representation of the sequential delivery system. Data presented as fold change over the housekeeping gene GAPDH. * P < 0.05.

Finally, the optimal doses of IFNγ (250ng) and SIMV (10 μg) were tested together and compared to the delivery of either molecule delivered alone from bCaP coating. The adsorption of IFNγ (without SIMV in the bCaP coatings) caused upregulation of M1 markers at both the early and late time points (Figure 5A–C). However, upregulation of M1 markers was inhibited at later time points by the SIMV incorporated into the bCaP coating. Concurrently, at the later time points, there was upregulation of M2 markers by coatings containing SIMV with and without IFNγ adsorption (Figure 5 D, E), indicating that SIMV is both anti-inflammatory and M2-promoting.

Figure 5:

Gene expression for THP-1 cultured on bCaP surface with or without 250 ng IFNγ or 10 μg SIMV or both over 6 days. (A-C) M1 macrophage markers and (D and E) M2 macrophage markers. * P < 0.05.

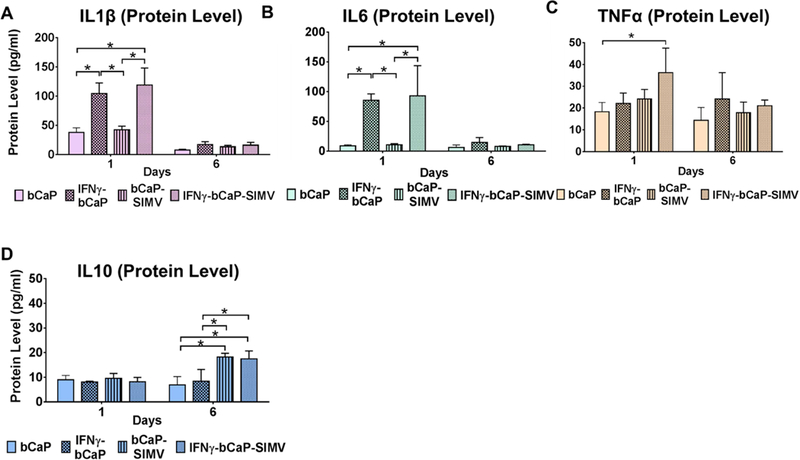

Cytokines released by THP-1 macrophages cultured on bCaP coatings with or without 250 ng of IFNγ and with 10 μg SIMV embedded under the bCaP coating were measured. IFNγ polarized THP-1-derived macrophages to the M1 phenotype at the early time point (1 day), as measured by increased expression of IL1β and IL6, as compared to the bCaP or bCaP-SIMV control (Figure new 6 A and B). TNFα was only significantly elevated in the IFNγ-bCaP-SIMV group as compared to other groups tested (Figure new 6 C). By day 6, the expression of IL6 and IL1β had reduced to baseline levels of macrophages cultured on bCaP while TNFα was not significantly different in all groups tested. The expression of IL10, an M2 marker, increased in all samples cultured on bCaP loaded with SIMV, but only at the day 6 time point (Figure new 6 D).

Figure 6:

Cytokine protein expression of THP-1 human peripheral blood macrophages over time when cultured on bCaP with 250 ng IFNγ on the exterior and/or 10 μg SIMV below the bCaP barrier layer as compared to culture on the bCaP layer only. (A-C) Cytokines associated with an M1 phenotype. (D) Cytokine associated with M2. * P < 0.05.

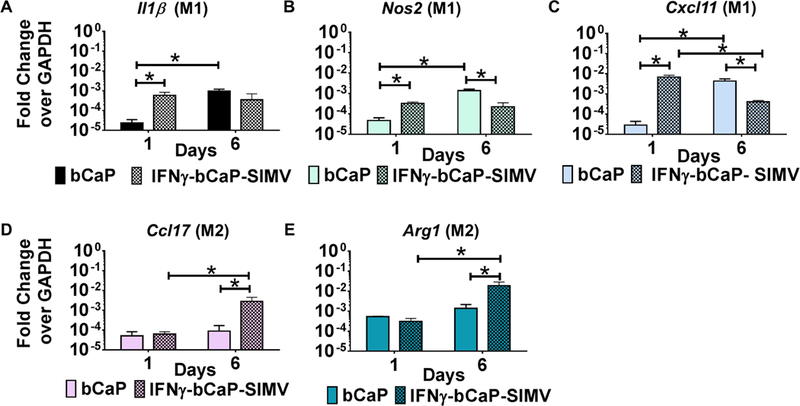

3.4. Response of primary murine macrophages to the sequential delivery system

The ability of the sequential delivery system to polarize primary cells was tested in bone marrow derived macrophages from both aged (25 months) and adult C57/B16 male mice. As hypothesized, the sequential delivery of 250 ng IFNγ followed by 10 μg SIMV from bCaP resulted in elevation of M1 markers on day 1, as measured by the gene expression of Il1β, Nos2 and Cxcl11, compared to cells cultured on bCaP control with no stimuli (Figure 7 A–C). The M2 markers Ccl17 and Arg1 were elevated on day 6 of culture compared to cells grown on bCaP (Figure 7 D and E).

Figure 7:

Gene expression of murine bone marrow derived macrophages over time when cultured on bCaP with 250 ng IFNγ on the exterior and 10 μg SIMV below the bCaP barrier layer as compared to culture on the bCaP layer only. (A-C) M1 markers. (D and E) M2 markers. * P < 0.05.

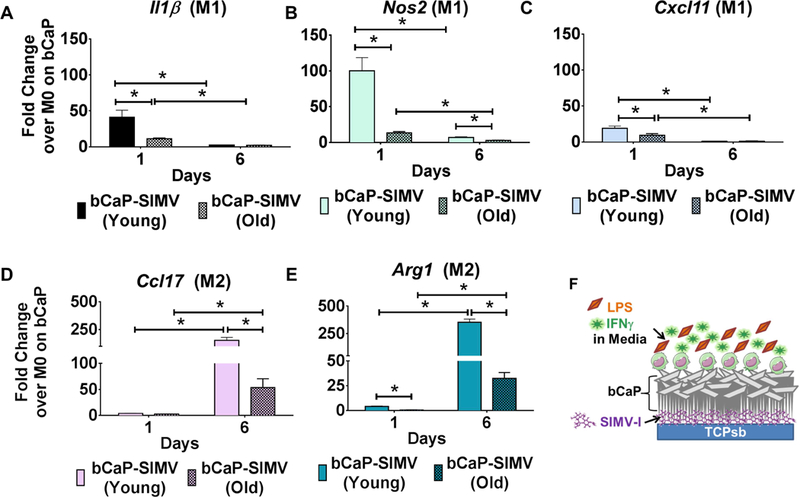

Given reports of age-related alterations to macrophages, the effects of localized delivery SIMV by bCaP on M2 polarization of old macrophages were compared to the effects on macrophages from adult mice. Since the effect of IFNγ in the media on old vs. young BMM was established in the literature (21), the goal of these experiments was to identify new effects from delayed delivery of SIMV by the bCaP. In these studies, initial inflammatory conditions were induced by LPS and IFNγ included in the media for 3 days and not delivered by the bCaP. The expected initial inflammatory response arose from IFNγ and LPS in both young and aged macrophages as evidenced by an increase of M1 markers (Il1β, Nos2 and Cxcl11). A successful shift to the M2 phenotype was seen on day 6 for both ages (Figure 8). Interestingly, there was a significant reduction in both M1 and M2 response of old macrophages to stimuli as compared to macrophages derived from the younger animals.

Figure 8:

A comparison of the gene expression of primary bone marrow macrophages from young adult and old mice during culture on bCaP with 10 μg SIMV below the bCaP barrier layer. The M1 stimuli LPS and IFNγ were in the culture medium for the first 3 days. (A-C) M1 macrophage markers. (D, E) M2 macrophage markers. Data normalized to GAPDH and then expressed as fold change over M0 macrophages cultured on bCaP. * P < 0.05.

4. Discussion

Older individuals are at risk for increased falls, are more likely to suffer from fractures and have delayed bone healing due to an extended inflammatory response during fracture healing (59–61). Inflammatory processes regulate skeletal cell activity through the release of cytokines and chemokines secreted by macrophages (62–64). There is a need for therapeutic approaches that modulate impaired aged macrophage polarization to improve bone regeneration outcomes in older patients. A variety of strategies to activate M1 or M2 macrophage phenotypes have been pursued in the context of improving osteogenesis (9, 65–68), but very few studies have been conducted in elderly animals that have impaired macrophage responses. Inhibition of inflammatory macrophages in elderly mice with fractures was reported to prevent delayed healing of old mice (69). That study administered macrophage modulating drugs to the mice to improve bone formation via systemic delivery for 10 days in their food. The novelty of the present study was to design a localized delivery system using factors known to positively influence osteoblast differentiation and to guide the transition of macrophages. Both the bCaP coating and SIMV contribute positively to new bone formation (70–73). This work paves the way for application of the bCaP delivery system to bone grafts which could be placed in open fractures or bone defects as a means to locally, in a site specific way, without systemic side effects, control host macrophage response and concurrently improve bone formation.

It is known that the aging process impairs the initiation of the M1 response and delays the M2 polarization in response to stimuli (12, 13, 24, 74, 75); however, to our knowledge there are no studies that have evaluated the effects of locally delivered therapies from a biomaterial on the modulation of macrophages from old mice. In the present study we confirmed the ability of a bCaP biomaterial coating to polarize the impaired old mouse macrophages BMDM with sequential delivery of IFNγ followed by SIMV from bCaP in highly localized manner. It has been shown previously that the addition of a bCaP barrier layer to a poly-L-lysine/poly-L-glutamic acid polyelectrolyte multilayer coating effectively provided highly localized, cell mediated, sequential delivery of two biomolecules to osteoprogenitor cells (54), but it was unknown if bCaP alone could deliver two molecules and temporally guide macrophage polarization.

The physical and chemical properties of the biomaterial can influence macrophage modulation. For example, it has been reported that calcium and strontium ions on a nanostructure titanium surface can increase M2 macrophage phenotype (76). Another study reported that hydroxyapatite granules activate some M1, but more M2 activation of THP-1 cells (77). In the present studies, the bCaP coating, which is carbonated hydroxyapatite in the form of a coating rather than in granules, was a potent M1 stimulator for THP-1 cells, and then transitioned to M2 via simvastatin delivery. The bCaP coating has islands of crystals and the junctions of those islands are sites of lower coating density (21). Despite the sparingly soluble nature of the bCaP, there appears to be a dissolution of the coating that occurs in culture that enables release of the simvastatin after a few days. Further studies are needed to understand the degradation of the bCaP delivery system in the presence of macrophages. An appropriate amount of inflammation and granulation tissue formation is a prerequisite for healthy and successful bone healing outcome, so the M1 stage is essential and the delayed delivery of simvastatin allowed M1. Furthermore, given the ability of M1 macrophages to stimulate angiogenesis during tissue regeneration (78, 79), the enhanced M1 macrophage phenotype induced by the bCaP coating may contribute positively to tissue repair.

The underlying mechanism by which SIMV modulates macrophage phenotype has not been fully elucidated, but it is known that SIMV reduces pro-inflammatory cytokines that drive the M1 phenotype (48–51). Our results suggest that the dose of SIMV we tested promotes a hybrid M2 phenotype, characterized by both M2a and M2c markers (CCL17 and CD163, respectively), which could be mediated through its increase in IL-10 (50, 51). Others have previously shown that anti-inflammatory actions of simvastatin result in better bone repair outcomes because of down regulation of resorptive osteoclast activity in models of periodontitis (51). However, a slight increase in expression of two of the M1 markers was seen at the 10 μg dose of SIMV tested. It has been reported that SIMV caused swelling and inflammatory tissue reactions at milligram doses when implanted in rats (80, 81). Further in vitro and in vivo dose response studies are needed to determine how to optimize the balance between inflammation and the resolution of inflammation in order to get a net gain during osteogenesis in older animals.

The phenotype of a macrophage changes over time to control bone healing events (79–85). The importance of the timing of macrophage modulation to osteogenesis was previously demonstrated in vitro by pipetting in IL-4 to M1-macrophages co-cultured with osteoprogenitors (66). Only the delayed addition of IL-4 enhanced osteoblastic differentiation as compared to its immediate administration. Appropriate temporal control over macrophage polarization is required to achieve the pro-anabolic contributions of macrophages to bone repair. The bCaP biomaterial system tested in the present studies provided a similarly timed, delayed modulation of macrophage polarization and thus may be an ideal design to promote osteogenesis. However, this study did have some limitations. First, we only evaluated gene expression of a handful of M1 and M2 markers although the protein expression data obtained in these studies did confirm the gene expression results. Although gene expression has been shown in multiple studies to be a very thorough way to phenotype macrophages (86), it is not yet known if the M1 and M2 phenotypes promoted by the bCaP delivery system will induce in vivo bone repair in old mice. It is also not yet known what dose of SIMV is required to obtain positive effects on in vivo bone formation. These limitations notwithstanding, the results of the present study advance the design of immunomodulatory biomaterials that can modulate the behavior of aged macrophages.

5. Conclusions

The dysfunctional macrophage of the older person is a target for new approaches to improve bone formation and accelerate repair of bone injuries in the older person. These studies showed that a bioinspired apatite coating is an effective means of temporally separating delivery of an M1 macrophage-promoting stimulus from an M2 macrophage-promoting stimulus, resulting in effective M1-to-M2 phenotype transitions of THP-1 macrophages. The delivery of IFNγ followed by SIMV from bCaP was shown to successfully guide macrophage phenotype transitinos in a macrophage cell line from a young human, as well as primary macrophages derived from adult and old mice. These findings suggest that delivery of immunomodulatory molecules from bCaP is a valuable strategy that should be pursued as a means of increasing bone formation in older patients who suffer from age-related impairments in macrophage function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) R01DE021103 to LTK and NIH/NHLBI HL130037 to KLS. The authors would like to thank Dr. Sun-Kyeong Lee for providing guidance on the mouse bone marrow culture procedures. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data Availability

The raw/processed data required to reproduce these findings cannot be shared at this time due to technical or time limitations.

References

- 1.Alexander KA, Chang MK, Maylin ER, Kohler T, Muller R, Wu AC, et al. Osteal macrophages promote in vivo intramembranous bone healing in a mouse tibial injury model. J Bone Miner Res 2011;26(7):1517–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarique AA, Logan J, Thomas E, Holt PG, Sly PD, Fantino E. Phenotypic, functional, and plasticity features of classical and alternatively activated human macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2015;53(5):676–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ishikawa M, Ito H, Kitaori T, Murata K, Shibuya H, Furu M, et al. MCP/CCR2 signaling is essential for recruitment of mesenchymal progenitor cells during the early phase of fracture healing. PLoS One 2014;9(8):e104954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Celada A, Gray PW, Rinderknecht E, Schreiber RD. Evidence for a gamma-interferon receptor that regulates macrophage tumoricidal activity. J Exp Med 1984;160(1):55–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spiller KL, Koh TJ. Macrophage-based therapeutic strategies in regenerative medicine. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2017;122:74–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lurier EB, Dalton D, Dampier W, Raman P, Nassiri S, Ferraro NM, et al. Transcriptome analysis of IL-10-stimulated (M2c) macrophages by next-generation sequencing. Immunobiology 2017;222(7):847–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirza R, Koh TJ. Dysregulation of monocyte/macrophage phenotype in wounds of diabetic mice. Cytokine 2011;56(2):256–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kigerl KA, Gensel JC, Ankeny DP, Alexander JK, Donnelly DJ, Popovich PG. Identification of two distinct macrophage subsets with divergent effects causing either neurotoxicity or regeneration in the injured mouse spinal cord. J Neurosci 2009;29(43):13435–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spiller KL, Nassiri S, Witherel CE, Anfang RR, Ng J, Nakazawa KR, et al. Sequential delivery of immunomodulatory cytokines to facilitate the M1-to-M2 transition of macrophages and enhance vascularization of bone scaffolds. Biomaterials 2015;37:194–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graney PL, Lurier EB, Spiller KL. Biomaterials and Bioactive Factor Delivery Systems for the Control of Macrophage Activation in Regenerative Medicine. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franceschi C, Bonafe M, Valensin S, Olivieri F, De Luca M, Ottaviani E, et al. Inflamm-aging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000;908:244–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibon E, Loi F, Cordova LA, Pajarinen J, Lin T, Lu L, et al. Aging Affects Bone Marrow Macrophage Polarization: Relevance to Bone Healing. Regen Eng Transl Med 2016;2(2):98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahbub S, Deburghgraeve CR, Kovacs EJ. Advanced age impairs macrophage polarization. J Interferon Cytokine Res 2012;32(1):18–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swift ME, Burns AL, Gray KL, DiPietro LA. Age-related alterations in the inflammatory response to dermal injury. J Invest Dermatol 2001;117(5):1027–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chelvarajan RL, Collins SM, Van Willigen JM, Bondada S. The unresponsiveness of aged mice to polysaccharide antigens is a result of a defect in macrophage function. J Leukoc Biol 2005;77(4):503–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boehmer ED, Goral J, Faunce DE, Kovacs EJ. Age-dependent decrease in Toll-like receptor 4-mediated proinflammatory cytokine production and mitogen-activated protein kinase expression. J Leukoc Biol 2004;75(2):342–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Renshaw M, Rockwell J, Engleman C, Gewirtz A, Katz J, Sambhara S. Cutting edge: impaired Toll-like receptor expression and function in aging. J Immunol 2002;169(9):4697–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sebastian C, Herrero C, Serra M, Lloberas J, Blasco MA, Celada A. Telomere shortening and oxidative stress in aged macrophages results in impaired STAT5a phosphorylation. J Immunol 2009;183(4):2356–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hachim D, Wang N, Lopresti ST, Stahl EC, Umeda YU, Rege RD, et al. Effects of aging upon the host response to implants. J Biomed Mater Res A 2017;105(5):1281–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Duin D, Mohanty S, Thomas V, Ginter S, Montgomery RR, Fikrig E, et al. Age-associated defect in human TLR-1/2 function. J Immunol 2007;178(2):970–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoon P, Keylock KT, Hartman ME, Freund GG, Woods JA. Macrophage hypo-responsiveness to interferon-gamma in aged mice is associated with impaired signaling through Jak-STAT. Mech Ageing Dev 2004;125(2):137–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lumeng CN, Liu J, Geletka L, Delaney C, Delproposto J, Desai A, et al. Aging is associated with an increase in T cells and inflammatory macrophages in visceral adipose tissue. J Immunol 2011;187(12):6208–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takayama T, Hirano-Kawamoto A, Yamamoto M, Murakami G, Katori Y, Kitamura K, et al. Macrophage infiltration into thyroid follicles: an immunohistochemical study using donated elderly cadavers. Okajimas Folia Anat Jpn 2016;93(3):73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stahl EC, Brown BN. Pro-Inflammatory Monocyte Derived Macrophages Accumulate in Uninjured Aged Murine Livers. The FASEB Journal 2017;31(1_supplement):328.9-.9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xing Z, Lu C, Hu D, Miclau T 3rd, Marcucio RS. Rejuvenation of the inflammatory system stimulates fracture repair in aged mice. J Orthop Res 2010;28(8):1000–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Danon D, Kowatch MA, Roth GS. Promotion of wound repair in old mice by local injection of macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1989;86(6):2018–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stein M, Keshav S, Harris N, Gordon S. Interleukin 4 potently enhances murine macrophage mannose receptor activity: a marker of alternative immunologic macrophage activation. J Exp Med 1992;176(1):287–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murray PJ, Allen JE, Biswas SK, Fisher EA, Gilroy DW, Goerdt S, et al. Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity 2014;41(1):14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jetten N, Roumans N, Gijbels MJ, Romano A, Post MJ, de Winther MP, et al. Wound administration of M2-polarized macrophages does not improve murine cutaneous healing responses. PLoS One 2014;9(7):e102994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li J, Baker BA, Mou X, Ren N, Qiu J, Boughton RI, et al. Biopolymer/Calcium phosphate scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Adv Healthc Mater 2014;3(4):469–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bigi A, Boanini E, Bracci B, Facchini A, Panzavolta S, Segatti F, et al. Nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite coatings on titanium: a new fast biomimetic method. Biomaterials 2005;26(19):4085–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim HM, Himeno T, Kokubo T, Nakamura T. Process and kinetics of bonelike apatite formation on sintered hydroxyapatite in a simulated body fluid. Biomaterials 2005;26(21):4366–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gronowicz G, Jacobs E, Peng T, Zhu L, Hurley M, Kuhn LT. (*) Calvarial Bone Regeneration Is Enhanced by Sequential Delivery of FGF-2 and BMP-2 from Layer-by-Layer Coatings with a Biomimetic Calcium Phosphate Barrier Layer. Tissue Eng Part A 2017;23(23–24):1490–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oliveira AL, Alves CM, Reis RL. Cell adhesion and proliferation on biomimetic calcium-phosphate coatings produced by a sodium silicate gel methodology. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2002;13(12):1181–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chesnutt BM, Viano AM, Yuan Y, Yang Y, Guda T, Appleford MR, et al. Design and characterization of a novel chitosan/nanocrystalline calcium phosphate composite scaffold for bone regeneration. J Biomed Mater Res A 2009;88(2):491–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schliephake H, Scharnweber D, Dard M, Robetaler S, Sewing A, Huttmann C. Biological performance of biomimetic calcium phosphate coating of titanium implants in the dog mandible. J Biomed Mater Res A 2003;64(2):225–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng Y, Wu G, Liu T, Liu Y, Wismeijer D, Liu Y. A novel BMP2-coprecipitated, layer-by-layer assembled biomimetic calcium phosphate particle: a biodegradable and highly efficient osteoinducer. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2014;16(5):643–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Y, Hunziker EB, Layrolle P, De Bruijn JD, De Groot K. Bone morphogenetic protein 2 incorporated into biomimetic coatings retains its biological activity. Tissue Eng 2004;10(1–2):101–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stigter M, Bezemer J, de Groot K, Layrolle P. Incorporation of different antibiotics into carbonated hydroxyapatite coatings on titanium implants, release and antibiotic efficacy. J Control Release 2004;99(1):127–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramirez-Rodriguez GB, Delgado-Lopez JM, Iafisco M, Montesi M, Sandri M, Sprio S, et al. Biomimetic mineralization of recombinant collagen type I derived protein to obtain hybrid matrices for bone regeneration. J Struct Biol 2016;196(2):138–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu Y, de Groot K, Hunziker EB. BMP-2 liberated from biomimetic implant coatings induces and sustains direct ossification in an ectopic rat model. Bone 2005;36(5):745–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Y, Zhang X, Liu Y, Jin X, Fan C, Ye H, et al. Bi-functionalization of a calcium phosphate-coated titanium surface with slow-release simvastatin and metronidazole to provide antibacterial activities and pro-osteodifferentiation capabilities. PLoS One 2014;9(5):e97741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao S, Wen F, He F, Liu L, Yang G. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of the osteogenic ability of implant surfaces with a local delivery of simvastatin. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2014;29(1):211–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang X, Jiang W, Liu Y, Zhang P, Wang L, Li W, et al. Human adipose-derived stem cells and simvastatin-functionalized biomimetic calcium phosphate to construct a novel tissue-engineered bone. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018;495(1):1264–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tuomisto TT, Lumivuori H, Kansanen E, Hakkinen SK, Turunen MP, van Thienen JV, et al. Simvastatin has an anti-inflammatory effect on macrophages via upregulation of an atheroprotective transcription factor, Kruppel-like factor 2. Cardiovasc Res 2008;78(1):175–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sakoda K, Yamamoto M, Negishi Y, Liao JK, Node K, Izumi Y. Simvastatin decreases IL-6 and IL-8 production in epithelial cells. J Dent Res 2006;85(6):520–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dombrecht EJ, Van Offel JF, Bridts CH, Ebo DG, Seynhaeve V, Schuerwegh AJ, et al. Influence of simvastatin on the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide by activated human chondrocytes. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2007;25(4):534–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rezaie-Majd A, Maca T, Bucek RA, Valent P, Muller MR, Husslein P, et al. Simvastatin reduces expression of cytokines interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in circulating monocytes from hypercholesterolemic patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2002;22(7):1194–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kagami S, Kanari H, Suto A, Fujiwara M, Ikeda K, Hirose K, et al. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor simvastatin inhibits proinflammatory cytokine production from murine mast cells. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2008;146 Suppl 1:61–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cicek Ari V, Ilarslan YD, Erman B, Sarkarati B, Tezcan I, Karabulut E, et al. Statins and IL-1beta, IL-10, and MPO Levels in Gingival Crevicular Fluid: Preliminary Results. Inflammation 2016;39(4):1547–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mouchrek Junior JCE, Macedo CG, Abdalla HB, Saba AK, Teixeira LN, Mouchrek A, et al. Simvastatin modulates gingival cytokine and MMP production in a rat model of ligature-induced periodontitis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent 2017;9:33–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li QZ, Sun J, Han JJ, Qian ZJ. [Anti-inflammation of simvastatin by polarization of murine macrophages from M1 phenotype to M2 phenotype]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2013;93(26):2071–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nadon NL. Exploiting the rodent model for studies on the pharmacology of lifespan extension. Aging Cell 2006;5(1):9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jacobs EE, Gronowicz G, Hurley MM, Kuhn LT. Biomimetic calcium phosphate/polyelectrolyte multilayer coatings for sequential delivery of multiple biological factors. J Biomed Mater Res A 2017;105(5):1500–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barrere F, Layrolle P, Van Blitterswijk CA, De Groot K. Biomimetic coatings on titanium: a crystal growth study of octacalcium phosphate. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2001;12(6):529–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goldberg AJ, Liu Y, Advincula MC, Gronowicz G, Habibovic P, Kuhn LT. Fabrication and characterization of hydroxyapatite-coated polystyrene disks for use in osteoprogenitor cell culture. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 2010;21(10):1371–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Habibovic PB FvB CA; de Groot K; Layrolle P . Biomimetic Hydroxyapatite Coating on Metal Implants. . Journal of American Ceramic Society 2002;85:517–22. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Spiller KL, Wrona EA, Romero-Torres S, Pallotta I, Graney PL, Witherel CE, et al. Differential gene expression in human, murine, and cell line-derived macrophages upon polarization. Exp Cell Res 2016;347(1):1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Clark D, Nakamura M, Miclau T, Marcucio R. Effects of Aging on Fracture Healing. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2017;15(6):601–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gomberg BF, Gruen GS, Smith WR, Spott M. Outcomes in acute orthopaedic trauma: a review of 130,506 patients by age. Injury 1999;30(6):431–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Manolagas SC, Parfitt AM. What old means to bone. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2010;21(6):369–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Glass GE, Chan JK, Freidin A, Feldmann M, Horwood NJ, Nanchahal J. TNF-alpha promotes fracture repair by augmenting the recruitment and differentiation of muscle-derived stromal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011;108(4):1585–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gerstenfeld LC, Cho TJ, Kon T, Aizawa T, Cruceta J, Graves BD, et al. Impaired intramembranous bone formation during bone repair in the absence of tumor necrosis factor-alpha signaling. Cells Tissues Organs 2001;169(3):285–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ito H Chemokines in mesenchymal stem cell therapy for bone repair: a novel concept of recruiting mesenchymal stem cells and the possible cell sources. Mod Rheumatol 2011;21(2):113–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pajarinen J, Tamaki Y, Antonios JK, Lin TH, Sato T, Yao Z, et al. Modulation of mouse macrophage polarization in vitro using IL-4 delivery by osmotic pumps. J Biomed Mater Res A 2015;103(4):1339–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Loi F, Cordova LA, Zhang R, Pajarinen J, Lin TH, Goodman SB, et al. The effects of immunomodulation by macrophage subsets on osteogenesis in vitro. Stem Cell Res Ther 2016;7:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li T, Peng M, Yang Z, Zhou X, Deng Y, Jiang C, et al. 3D-printed IFN-gamma-loading calcium silicate-beta-tricalcium phosphate scaffold sequentially activates M1 and M2 polarization of macrophages to promote vascularization of tissue engineering bone. Acta Biomater 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brown BN, Londono R, Tottey S, Zhang L, Kukla KA, Wolf MT, et al. Macrophage phenotype as a predictor of constructive remodeling following the implantation of biologically derived surgical mesh materials. Acta Biomater 2012;8(3):978–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Slade Shantz JA, Yu YY, Andres W, Miclau T 3rd, Marcucio R. Modulation of macrophage activity during fracture repair has differential effects in young adult and elderly mice. J Orthop Trauma 2014;28 Suppl 1:S10–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang L, Zhang B, Bao C, Habibovic P, Hu J, Zhang X. Ectopic osteoid and bone formation by three calcium-phosphate ceramics in rats, rabbits and dogs. PLoS One 2014;9(9):e107044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Daculsi G FBH, Miramond T. The Essential Role of Calcium Phosphate Bioceramics in Bone Regeneration In: Ben-Nissan B (eds) Advances in Calcium Phosphate Biomaterials. Springer Series in Biomaterials Science and Engineering, vol 2 Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Edwards CJ, Hart DJ, Spector TD. Oral statins and increased bone-mineral density in postmenopausal women. Lancet 2000;355(9222):2218–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Montagnani A, Gonnelli S, Cepollaro C, Pacini S, Campagna MS, Franci MB, et al. Effect of simvastatin treatment on bone mineral density and bone turnover in hypercholesterolemic postmenopausal women: a 1-year longitudinal study. Bone 2003;32(4):427–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barrett JP, Costello DA, O’Sullivan J, Cowley TR, Lynch MA. Bone marrow-derived macrophages from aged rats are more responsive to inflammatory stimuli. J Neuroinflammation 2015;12:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brown BN, Haschak MJ, Lopresti ST, Stahl EC. Effects of age-related shifts in cellular function and local microenvironment upon the innate immune response to implants. Semin Immunol 2017;29:24–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee CH, Kim YJ, Jang JH, Park JW. Modulating macrophage polarization with divalent cations in nanostructured titanium implant surfaces. Nanotechnology 2016;27(8):085101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fernandes KR, Zhang Y, Magri AMP, Renno ACM, van den Beucken J. Biomaterial Property Effects on Platelets and Macrophages: An in Vitro Study. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2017;3(12):3318–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Spiller KL, Anfang RR, Spiller KJ, Ng J, Nakazawa KR, Daulton JW, et al. The role of macrophage phenotype in vascularization of tissue engineering scaffolds. Biomaterials 2014;35(15):4477–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Willenborg S, Lucas T, van Loo G, Knipper JA, Krieg T, Haase I, et al. CCR2 recruits an inflammatory macrophage subpopulation critical for angiogenesis in tissue repair. Blood 2012;120(3):613–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stein D, Lee Y, Schmid MJ, Killpack B, Genrich MA, Narayana N, et al. Local simvastatin effects on mandibular bone growth and inflammation. J Periodontol 2005;76(11):1861–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ito T, Takemasa M, Makino K, Otsuka M. Preparation of calcium phosphate nanocapsules including simvastatin/deoxycholic acid assembly, and their therapeutic effect in osteoporosis model mice. J Pharm Pharmacol 2013;65(4):494–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Arora M, Chen L, Paglia M, Gallagher I, Allen JE, Vyas YM, et al. Simvastatin promotes Th2-type responses through the induction of the chitinase family member Ym1 in dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103(20):7777–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Andrew JG, Andrew SM, Freemont AJ, Marsh DR. Inflammatory cells in normal human fracture healing. Acta Orthop Scand 1994;65(4):462–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Xing Z, Lu C, Hu D, Yu YY, Wang X, Colnot C, et al. Multiple roles for CCR2 during fracture healing. Dis Model Mech 2010;3(7–8):451–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kon T, Cho TJ, Aizawa T, Yamazaki M, Nooh N, Graves D, et al. Expression of osteoprotegerin, receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand (osteoprotegerin ligand) and related proinflammatory cytokines during fracture healing. J Bone Miner Res 2001;16(6):1004–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xue J, Schmidt SV, Sander J, Draffehn A, Krebs W, Quester I, et al. Transcriptome-based network analysis reveals a spectrum model of human macrophage activation. Immunity 2014;40(2):274–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.