Abstract

Introduction:

Shoulder arthroscopies are among the most frequently performed surgeries by orthopaedic surgeons. Little is known about complication rates among recently trained surgeons. The purpose of this study was to examine the type and frequency of complications of common arthroscopic shoulder procedures performed by candidates challenging the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery: Part II, certification examination.

Methods:

Data were obtained from the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery database for orthopaedic surgeons who sat for the part II examination from 2012 to 2016. In total, 27,072 procedures were reviewed. The database was queried to determine the type and frequency of complications for patients who underwent shoulder arthroscopy, including arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, labrum repair, biceps tenodesis, and bony/soft tissue débridement procedures. Complications were classified as surgical, anesthetic, or medical. Factors affecting complication rates were investigated including surgeon's fellowship training, geographic location, and patients’ age and sex.

Results:

Patients with surgical complications (n = 2,133; 7.9%) were more common than anesthetic (n = 263; 1.0%) or medical (n = 607; 2.2%) complications. There was a significant variation in the surgical complication rate among different arthroscopic shoulder procedures, ranging from 5.4% for labral repair to 10.3% for rotator cuff repair and biceps tenodesis. Stiffness/arthrofibrosis was the most commonly recorded surgical complication (2.2%). Surgical complication rates were lowest in the Northeast region (6.7%; P < 0.01) and in patients younger than 21 years (3.8%; P < 0.01). Women had significantly higher rate of complications than men (8.4% versus 7.6%; P = 0.02). Among anesthetic-related complications, 61.6% were related to regional nerve blocks. The overall revision surgery and readmission rates were 0.8% and 1.0%, respectively.

Conclusion:

The overall self-reported surgical complication rate for arthroscopic shoulder procedures was 7.9%, which is higher than the rates reported in the literature. Although the rate of anesthetic complications is low (1.0%), adverse events related to nerve blocks made up most of the overall anesthetic related complications.

Shoulder arthroscopy is the second most commonly performed surgery by candidates participating in the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery (ABOS): Part II, certification examination.1 With growth in the aging population and athletically active elderly and with improvements in arthroscopic surgical implants and techniques, the ability to treat patients with reliable arthroscopic procedures rather than through open surgery has resulted in increased popularity of shoulder arthroscopy. As a result, the number of shoulder arthroscopic procedures including rotator cuff repairs is increasing.2

In the United States, musculoskeletal disease accounts for more than $1 trillion annually in health care and related indirect expenses.3 Postoperative complications cause a significant social, mental, and economic burden including patient well-being, loss of productivity and increased healthcare expenses.4 Identifying factors that result in complications in commonly performed procedures is important for reducing further complications and will help focus quality improvement efforts. Such data can be used to mitigate the anticipated problems, resulting in improved outcomes and decreasing costs.5

Recent studies analyzing multi-institutional outcomes database have reported low overall complication rates (1.0% to 1.6%) after shoulder arthroscopy.6,7 However, there is a relative paucity of literature on complications after shoulder arthroscopy especially performed by surgeons who are early in their career. Learning curve as well as correlation of complications with surgeon volume is well documented in orthopaedics.8-10 Moreover, recent studies have examined learning curves unique to shoulder arthroscopy. Development of the ABOS database has resulted in improved reporting of practice trends in orthopaedic surgery.11 This database used by the Part-II candidates provides a relatively complete, robust, and accurate assessment of practice, procedures, and complications over a 6-month period, by surgeons who are relatively early in their career. The purpose of this study is to examine the type and frequency of complications of common arthroscopic shoulder procedures performed by candidates challenging the ABOS Part II examination. We hypothesized that surgical complication rates would not be different than what has been reported in the literature for shoulder arthroscopy.

Methods

After receiving institutional review board exemption, a retrospective review of the ABOS database was performed to analyze complications after shoulder arthroscopy. This database contains information voluntarily submitted by candidates who have already passed part I of the orthopaedic board examination. From April through September of the year before the examination, the candidates enter all cases including complications that occurred within 30 days of the end of the collection period into a securely maintained surgical log. Details of the ABOS database have been described in previous publications.11,12

The ABOS database was queried to generate data from the previous 5 years (2012 to 2016). The database was searched for all cases of arthroscopic shoulder surgery using the Current Procedural Terminology codes (29805 to 29807 and 29819 to 29828). The procedures were categorized into the following groups: Débridement (including loose body removal and bony resection procedures without labral, biceps, or rotator cuff work), Labrum (labral repair without rotator cuff repair), Rotator cuff (rotator cuff repair without labrum or biceps work), Rotator cuff + Labrum (concomitant rotator cuff and labral repair), and Rotator cuff + Biceps (rotator cuff repair with open or arthroscopic biceps tenodesis). Groups were based on invasiveness to aggregate procedures that would be expected to have similar complications.

Specific patient factors were gathered including sex and age. Surgeon factors, including geographic location of practice (Northeast, Midwest, Northwest, Southeast, South, and Southwest) and fellowship training (sports, shoulder and elbow, and hand and upper extremity) were extracted from the database. The recorded complications were divided into surgical (recurrent pain, stiffness/arthrofibrosis, wound complication, bone fracture, tendon/ligament failure, implant failure, hematoma, vascular injury, nerve palsy, wrong-sided surgery, and surgical unspecified), medical (venothromboembolism, pneumonia, respiratory failure, arrhythmia, congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident, renal failure, patient expiration, and medical unspecified complication), and anesthetic (unspecified and block-related). Additionally, the overall readmission and reoperation rate were calculated.

Routine descriptive statistics were calculated for complications of all arthroscopic shoulder procedures. Frequencies were obtained, and chi square tests were conducted for analysis of categorical variables in contingency tables. The α level for statistical significance was set at <0.05. All P values were rounded to the nearest 100th for uniformity. Data management was performed using Excel spreadsheets (Microsoft), and statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software).

Results

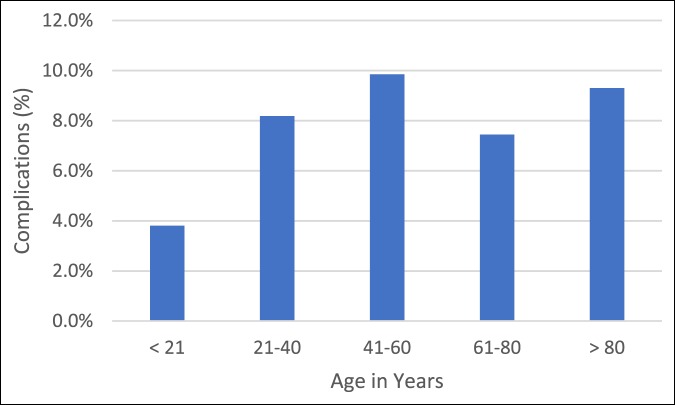

From the 2012 to 2016 board collection period, 27,072 arthroscopic shoulder cases were identified in the ABOS database. Surgical complications (7.9%) were the most common category of complications. Medical (2.2%) and anesthetic complications (1.0%) were less frequent. Overall rate of readmission and revision surgery were low (Table 1).

Table 1.

Frequency of Complications

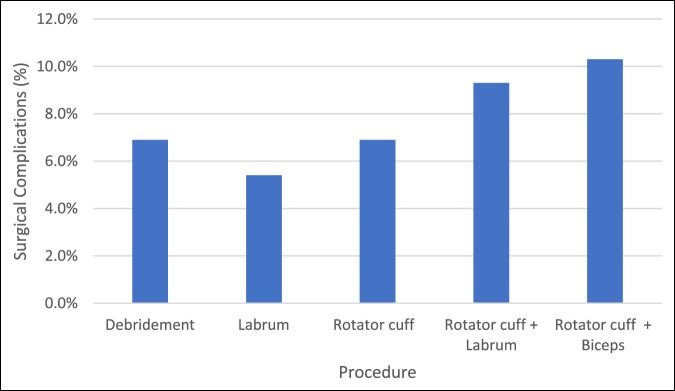

Complication rates for various arthroscopic shoulder procedures ranged from 5.4% for labrum type of procedures to 10.3% for rotator cuff repair and biceps tenodesis (Figure 1). Looking at specific complications, stiffness/arthrofibrosis and persistent pain were most frequently reported. Devastating surgical complications such as vascular injury and wrong-side surgery were exceedingly rare in shoulder arthroscopy with four and two cases reported, respectively. Frequencies of select surgical and medical complications are presented in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Surgical complication rates by procedure type.

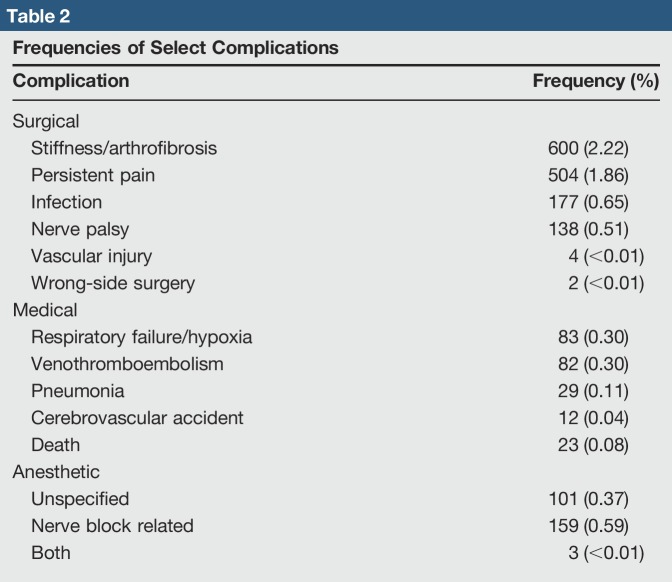

Table 2.

Frequencies of Select Complications

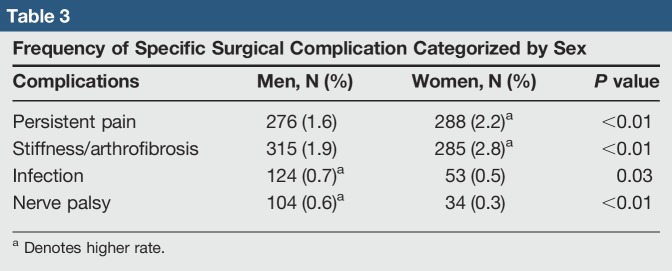

The number of men who underwent such surgeries was 16, 781 (62.0%). When analyzing the surgical complication rate by sex, overall, women had significantly higher rate of complications than men (8.4% versus 7.6%). Whereas persistent pain and stiffness/arthrofibrosis were more common in women, infection and nerve palsy were significantly more frequent in men (Table 3).

Table 3.

Frequency of Specific Surgical Complication Categorized by Sex

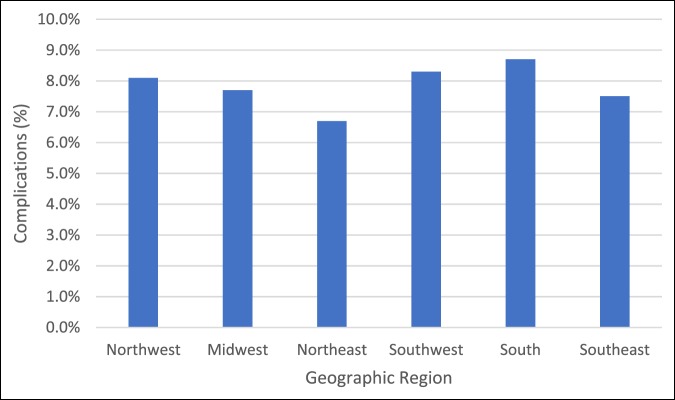

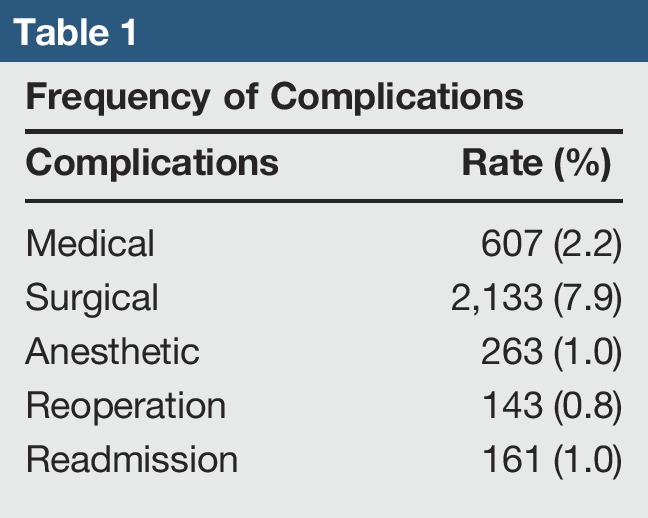

Surgeons who were fellowship-trained had higher overall complications than those who were not fellowship-trained (8.8% versus 7.4%; P < 0.01). There was geographic variability in the rate of surgical complications as well. The Northeast region reported the lowest rate of complications (6.7%; P < 0.01). There were no statistically significant differences in the rates of surgical complications in the remaining geographic regions within the United States (Figure 2). Patients younger than 21 years had the lowest rate of complications (3.8%), whereas patients between ages 21 to 40 had the highest rate of complications (9.9%) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Surgical complication rates by geographic region.

Figure 3.

Surgical complication rates by age.

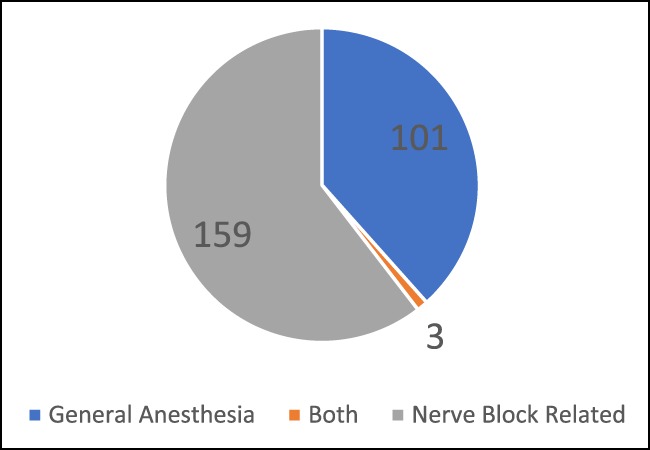

Although the overall rate of anesthetic complications was low (1.0%), 61.6% of the total anesthetic complications were attributed to nerve block-related issues (Figure 4). There were no differences in the rate of anesthetic complications by patient sex (P = 0.14).

Figure 4.

Frequency of anesthetic complications.

Discussion

The main findings of this analysis are that the rate of surgical, medical, and anesthetic complications are 7.9%, 2.2%, and 1.0%, respectively. Although arthroscopic surgeries are minimally invasive and most cases are performed in the outpatient setting, the overall rate of complications is not insignificant. The rate of surgical complications is also higher than that reported in the literature.6,7 Patients at increased risk of complications after shoulder arthroscopy should be identified preoperatively to improve outcomes and reduce costs.5 Moreover, patients should be appropriately counseled regarding the risk of complications.

Using the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database for the years 2005 to 2011, Shields et al7 reported a 1% complication rate after shoulder arthroscopy. The authors reported return to operating room and superficial surgical site infection were the most common major and minor complications, respectively.7 In another study of over 7,000 patients, using the NSQIP database, Rubenstein et al6 similarly reported an overall adverse event rate of 1.6%. However, the NSQIP database is a voluntary program in which participating hospitals collect and submit limited data (20% of cases in high-volume participating centers). Moreover, whereas Shields et al7 and Rubenstein et al6 reported complications that occurred within 30 days after surgery, the ABOS database contains information from every case performed during the entire collection period. Whereas stiffness/arthrofibrosis was the most common surgical complication identified in the current study, Shields et al7 noted that stiffness is a clinical outcome that cannot be assessed using a database which keeps track of early complications. Thus, it is difficult to make a direct comparison as the ABOS data represent a more complete and longitudinal database.

Another important consideration regarding the higher complication rates is that ABOS applicants are generally less experienced surgeons than their board-certified counterparts. This database represents information gathered from surgeons who are early in their independent careers and should not be seen as generalizable to all surgeons. The “learning curve” concept in orthopaedic surgery and more specifically in arthroscopic procedures has been well documented.9,13,14 Improved clinical and radiographic outcomes, decreased operative time, and lower complication rates have been associated with higher surgeon experience.9,15 A surgeon who is in the early phase of practice is unlikely to have the same clinical acumen, indication for surgery, or task efficiency in the operating room. Patient outcomes may reflect clinical skills of the surgeon, which is developed through practice, experience, knowledge, and continuous critical analysis acquired in-training as well as through independent practice.16 Therefore, although the complications rates in this database may be higher than what is quoted in the literature, it is possible that the results of these surgeons may normalize with experience and increased proficiency.

There was a significant variation in the surgical complication rate among different arthroscopic shoulder procedures, ranging from 5.4% for labral repair to 10.3% for rotator cuff repair and biceps tenodesis. Erickson et al17 reported significantly higher revision surgery rates at 6 months and 1 year in patients who underwent rotator cuff repair and concomitant biceps tenodesis, compared with rotator cuff repair alone. Concomitant rotator cuff repair and labral surgery had higher complications than either of the procedures had in isolation. Predictably, increasing complexity and added steps in cases resulted in higher complication rates.

Similarly to a previous study analyzing the ABOS database and rates of complication,12 the present study also noted significantly higher complication rates among surgeons with fellowship training compared with those without (8.8% versus 7.4%, respectively). This disparity may be explained by the potential differences in the complexity of cases (ie, revision case, massive rotator cuff tear, instability with more bone loss). However, like in the previous study, without patient-specific data for the 27,072 procedures, a multivariate analysis to determine whether case complexity played a factor in observed differences between fellowship-trained and untrained physicians cannot be determined. It may also represent differences in threshold for identifying and reporting surgical complications.

In a review of 9,410 cases also obtained through the NSQIP database, Martin et al18 reported no difference in complications between men or women after shoulder arthroscopy. On the contrary, Shields et al19 reported significantly higher complications in women after shoulder surgery. Whereas two previous studies combined and reported on all types of complications, the results from the current ABOS database, looking specifically at surgical complications, indicate that women had a higher rate than men. The findings are not unexpected as stiffness and persistent pain were the most common surgical complications in this study. The results of this study confirms previous observations that reported a higher rate of stiffness and pain in women after surgery.20-22 Women tend to report more stiffness as women tend to have a high level of difficulty in lifestyle domains such as styling hair and dressing or undressing. Moreover, Razmjou et al21 reported that emotionally, female patients have more difficulty than men. Others have attributed these differences to overall difference in symptom perception between genders.23

The overall reported rate of medical complications after surgery was 2.2%. Complications ranged from 0.3% for venothromboembolism (pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis) to 0.04% for cerebrovascular accidents. The ABOS database may represent an underestimate of the true medical complication rate because of the self-reporting process by orthopaedic surgeons rather than medical physicians. Nevertheless, a low rate of medical complications suggest that surgeons appropriately indicated patients who could withstand an arthroscopic procedure, for elective, quality-of-life-improving surgery.

Despite an overall anesthetic complication rate of 1.0%, nerve block-related issues made up a significant proportion of the complication (61.6%). Interscalene brachial plexus blocks are an effective anesthetic and analgesic method after arthroscopic shoulder surgery. Its use in outpatient surgery has resulted in earlier discharge, reduced narcotic usage, and increased patient satisfaction.24-26 Although complications after brachial plexus blocks are rare, devastating complications have been reported such as hemodynamic instability, respiratory depression, cardiac arrest, pneumothorax, and permanent nerve injury.25 Whereas ultrasound-guided injections are becoming standard of care and can minimize inaccurate injections, the less experienced anesthesiologists and community hospitals have been associated with increased complications.2,27 In contrast, in a review of over 15,000 cases of shoulder arthroscopy, performed in the beach chair position with an interscalene nerve block, over an 11-year period at a high-volume university setting ambulatory surgical center, the total rate of adverse events was 0.37%.28 Among this group of experienced anesthesiologists, only five nerve-related injuries were reported.

This study has limitations that are inherent to studies analyzing registries and databases. The data used in this study are self-reported by the ABOS applicants. Unlike figures such as revision surgery and readmission, which are absolute, candidate surgeons may have differing definitions or thresholds to classify varying degrees of stiffness as a complication. The same is also true for patient-reported outcomes such as persistent pain. No validated functional outcome measures or orthopaedic-specific parameters such as range of motion or pain scale are available in this database. Owing to a lack of strict, uniform definitions and criteria, candidates may have under- or overreported their complications. Additionally, specific details about the procedures and on why patients were readmitted or underwent revision surgery were unavailable. Another weakness of this study is that we did not analyze specific factors that increased the risk of complication for each category of shoulder procedure—as it was not the aim of this study. Additionally, type of anesthesia, surgical positioning, and anesthesiologist training or experience were not recorded; therefore, these factors were not investigated as potential predictors of outcome. Lastly, the length of time during which complications were reported is variable. For example, if a case was performed at the beginning of the collection period, the complication collection time would be 7 months compared with a case performed at the end of the period where collection time would be 30 days. As a result, in this database, complications that may have occurred outside the collection period would not have been accounted. Results of this study should be interpreted and used with caution. This study reports on outcomes of relatively novice surgeons. With increasing emphasis on bundled cost of care and hospitals facing responsibility for related costs, treatment of high-risk patients could be rationed by providers.5 Despite limitations of registries, such databases with high compliance and large numbers can provide comprehensive data on orthopaedic procedures and their outcomes, which may improve patient expectations and surgical practice.

Conclusion

The overall self-reported surgical complication rate for arthroscopic shoulder procedures was 7.9%, which is higher than the rates reported in the literature. The most common complications are stiffness and residual pain. Although the rate of anesthetic complications is low (1.0%), adverse events related to nerve blocks made up most of the overall anesthetic-related complications.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery for providing the data. The authors acknowledge John Harrast, PhD, and Clair Smith, MS, for their assistance with data analysis.

Footnotes

Dr. Irrgang or an immediate family member serves as a board member, owner, officer, or committee member of American Physical Therapy Association. Dr. Musahl or an immediate family member serves as a paid consultant to Smith & Nephew; has received research or institutional support from Coulter and Department of Defense; and serves as a board member, owner, officer, or committee member of American Orthopaedic Society for Sport Medicine and International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery, and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine. Dr. Lin or an immediate family member serves as a paid consultant to Arthrex and Tornier and serves as a board member, owner, officer, or committee member of American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons. None of the following authors or any immediate family member has received anything of value from or has stock or stock options held in a commercial company or institution related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article: Dr. Shin and Dr. Popchak.

The study was categorized as IRB Exempt as this research involves studying existing data where the subjects cannot be identified.

References

- 1.Garrett WE, Swiontkowski MF, Weinstein JN, et al. : American board of orthopaedic surgery practice of the orthopaedic surgeon: Part-II, certification examination case mix. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:660-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber SC, Abrams JS, Nottage WM: Complications associated with arthroscopic shoulder surgery. Arthroscopy 2002;18:88-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). /research/data/meps/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marecek GS, Saltzman MD: Complications in shoulder arthroscopy. Orthopedics 2010;33:492-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossi MJ, Brand JC, Provencher MT, Lubowitz JH: Shoulder arthroscopy complication and readmission rates: Impact on value. Arthroscopy 2017;33:4-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubenstein WJ, Pean CA, Colvin AC: Shoulder arthroscopy in adults 60 or older: Risk factors that correlate with postoperative complications in the first 30 days. Arthroscopy 2017;33:49-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shields E, Thirukumaran C, Thorsness R, Noyes K, Voloshin I: An analysis of adult patient risk factors and complications within 30 days after arthroscopic shoulder surgery. Arthroscopy 2015;31:807-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banaszek D, You D, Chang J, et al. : Virtual reality compared with bench-top simulation in the acquisition of arthroscopic skill: A randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2017;99:e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoppe DJ, de Sa D, Simunovic N, et al. : The learning curve for hip arthroscopy: A systematic review. Arthroscopy 2014;30:389-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandberg RP, Sherman NC, Latt LD, Hardy JC: Cigar box Arthroscopy: A randomized controlled trial validates nonanatomic simulation training of novice arthroscopy skills. Arthroscopy 2017;33:2015-2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patterson BM, Creighton RA, Spang JT, Roberson JR, Kamath GV: Surgical trends in the treatment of superior labrum anterior and posterior lesions of the shoulder analysis of data from the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery certification examination database. Am J Sports Med 2014;42:1904-1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salzler MJ, Lin A, Miller CD, Herold S, Irrgang JJ, Harner CD: Complications after arthroscopic knee surgery. Am J Sports Med 2014;42:292-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamakado K: Quantification of the learning curve for arthroscopic suprascapular nerve decompression: An evaluation of 300 cases. Arthroscopy 2015;31:191-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frank RM, Erickson B, Frank JM, et al. : Utility of modern arthroscopic simulator training models. Arthroscopy 2014;30:121-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castricini R, De Benedetto M, Orlando N, Rocchi M, Zini R, Pirani P: Arthroscopic latarjet procedure: Analysis of the learning curve. Musculoskelet Surg 2013;97(suppl 1):93-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kienle GS, Kiene H: Clinical judgement and the medical profession. J Eval Clin Pract 2011;17:621-627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erickson BJ, Basques BA, Griffin JW, et al. : The effect of concomitant biceps tenodesis on reoperation rates after rotator cuff repair: A review of a large private-payer database from 2007 to 2014. Arthroscopy 2017;33:1301-1307.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin CT, Gao Y, Pugely AJ, Wolf BR: 30-day morbidity and mortality after elective shoulder arthroscopy: A review of 9410 cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2013;22:1667-1675.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shields E, Iannuzzi JC, Thorsness R, Noyes K, Voloshin I: Postoperative morbidity by procedure and patient factors influencing major complications within 30 days following shoulder surgery. Orthop J Sports Med 2014;2:2325967114553164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Itoi E, Arce G, Bain GI, et al. : Shoulder stiffness: Current concepts and concerns. Arthroscopy 2016;32:1402-1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Razmjou H, Holtby R, Myhr T: Gender differences in quality of life and extent of rotator cuff pathology. Arthroscopy 2006;22:57-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Romeo AA, Hang DW, Bach BR, Shott S: Repair of full thickness rotator cuff tears: Gender, age, and other factors affecting outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999;243-255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz PP, Criswell LA: Differences in symptom reports between men and women with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 1996;9:441-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeske HC, Kralinger F, Wambacher M, et al. : A randomized study of the effectiveness of suprascapular nerve block in patient satisfaction and outcome after arthroscopic subacromial decompression. Arthroscopy 2011;27:1323-1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warrender WJ, Syed UAM, Hammoud S, et al. : Pain management after outpatient shoulder arthroscopy a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Am J Sports Med 2017;45:1676-1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee JJ, Kim DY, Hwang JT, et al. : Effect of ultrasonographically guided axillary nerve block combined with suprascapular nerve block in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: A randomized controlled trial. Arthroscopy 2014;30:906-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weber SC, Jain R: Scalene regional anesthesia for shoulder surgery in a community setting: An assessment of risk. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002;84-A:775-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rohrbaugh M, Kentor ML, Orebaugh SL, Williams B: Outcomes of shoulder surgery in the sitting position with interscalene nerve block: A single-center series. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2013;38:28-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]