Abstract

Background:

The aim of this meta-analysis is to assess the effectiveness of problem-based learning (PBL) in pediatric medical education in China.

Methods:

We searched Chinese electronic databases, including the China National Knowledge Infrastructure, WanFang Data, the China Science Periodical Database, and the Chinese BioMedical Literature Database. We also searched English electronic databases, including PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. We searched for published studies that compared the effects of PBL and traditional lecture-based learning (LBL) on students’ theoretical knowledge, skill, and case analysis scores during pediatric medical education in China. All randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included.

Results:

A total of 12 RCTs were included, with a total sample size of 1003 medical students. The PBL teaching model significantly increased theoretical knowledge scores (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.79–1.52; P < .00001), skill scores (95% CI, 0.87–2.25; P < .00001), and case analysis scores (P < .00001, I2 = 88%) compared with those using the LBL teaching model alone.

Conclusion:

The current meta-analysis shows that PBL in pediatric medical education in China appears to be more effective than the traditional teaching method in improving theoretical knowledge, skill, and case analysis scores. However, a more controlled design of RCT is needed to confirm the above conclusions in future work.

Keywords: lecture-based learning, meta-analysis, pediatric medical education, problem-based learning

1. Introduction

Problem-based learning (PBL) was originally introduced by Barrows and Tamblyn at McMaster University in the late 1960s.[1,2] In modern educational theory, it is believed that an ideal teaching method is beneficial for knowledge acquisition and practical skills. When compared to the traditional lecture-based learning (LBL) method, the PBL teaching method is more student centered. Students can solve problems and acquire knowledge through teacher-directed groups.[3–5] Many studies have shown that PBL students perform better in problem-solving and autonomous learning.[6–8] However, there is also evidence that the PBL teaching model is not superior to the LBL model in terms of knowledge acquisition in medical education.[9,10]

As an important branch of medical education, pediatrics is of great significance for medical students as they acquire basic clinical knowledge and skills.[11,12] Pediatric clinical teaching is a practical teaching process between the teachers and students. The ultimate purpose is to improve students’ clinical thinking ability and application of theoretical knowledge to solve practical problems. However, pediatric teaching has unique difficulties compared with adult clinical medicine disciplines. For example, due to the young age of pediatric patients, it is not easy for patients to communicate with the clinicians, which ultimately leads to difficulty in teaching and performing physical examinations. Therefore, it is very important to find a teaching method that can stimulate students’ interest, improve their ability to solve practical problems and cultivate their clinical thinking.

Unlike developed Western countries, the application of PBL in medical education is not a conventional teaching method in China for many reasons,[13] and the effectiveness of PBL education in pediatric medicine in China is still controversial. The aim of the current meta-analysis was to investigate the effectiveness of the PBL teaching model compared to the traditional teaching methods of pediatric medical education used in China. The purpose of this meta-analysis was to assess whether the PBL teaching model, when compared to traditional teaching, was associated with the following: higher theoretical knowledge scores, higher skill scores, and higher case analysis scores.

2. Materials and methods

The method used for this meta-analysis is based on the PRISMA checklist guidelines.[14] Ethical approval was unnecessary because this study is a review of previously published articles and does not involve access to individual participants’ data.

2.1. Search strategy

We searched Chinese electronic databases, including the China National Knowledge Infrastructure, WanFang Data, the China Science Periodical Database, and the Chinese BioMedical Literature Database. We also searched English electronic databases, including PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. The databases were systematically searched from inception up to June 2018. The following keywords were used: “problem-based learning OR PBL” AND “China OR Chinese” AND “pediatric OR children.” There were no language restrictions.

2.2. Inclusion criteria

The studies selected for the meta-analysis met the following criteria: the target population was pediatric medical students in China; the interventions used were PBL teaching in the experimental group and LBL teaching in the control group; the study design was controlled trials in pediatric medical education; and the outcome measurements included theoretical knowledge scores, skill scores, or case analysis scores in pediatric medicine. The exclusion criterion was the duplication of published literature, and if duplicate research was published, the study with the largest sample size was retained. All of the titles and abstracts were reviewed independently by the 2 reviewers (YM, XL). Any differences were resolved through consensus, and if necessary, a 3rd reviewer was consulted.

2.3. Assessment of methodologic quality

The methodologic quality of each study was evaluated independently by the 2 reviewers (YM, XL) using the Cochrane Collaboration for Systematic Reviews guidelines. The following seven items were assessed: random sequence generation, allocation sequence concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of the outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other biases. The overall methodologic quality of each included study was assessed as “low risk of bias,” “high risk of bias,” or “unclear risk of bias.”[15]

2.4. Data extraction and outcome measures

The 2 reviewers (YM, XL) independently extracted the eligibility study results from the predefined data fields. The following information was extracted: the 1st author's name, the published date, the study type, the number of participants, the major of the students, the course name, the school system, and the outcome measures. The outcome measures used in this meta-analysis were the theoretical knowledge scores, skill scores, and case analysis scores in both the PBL group and the LBL group.

2.5. Data synthesis

Statistical analyses were performed using RevMan 5 software (Version 5.3; Cochrane Collaboration, London, UK). The continuous data of the theoretical knowledge, skill, and case analysis scores were used to calculate the standardized mean difference with 95% confidence interval (CI). A test for heterogeneity was completed using the Chi-squared test and the I2 statistic. If the Chi-squared test >0.1 or if the I2 < 50%, the fixed effects model was used. A random-effects model was used if the Chi-squared test <0.1 or the I2 > 50%. Publication bias was assessed independently using funnel plots of the theoretical knowledge, skill, and case analysis scores.

3. Results

3.1. Search results

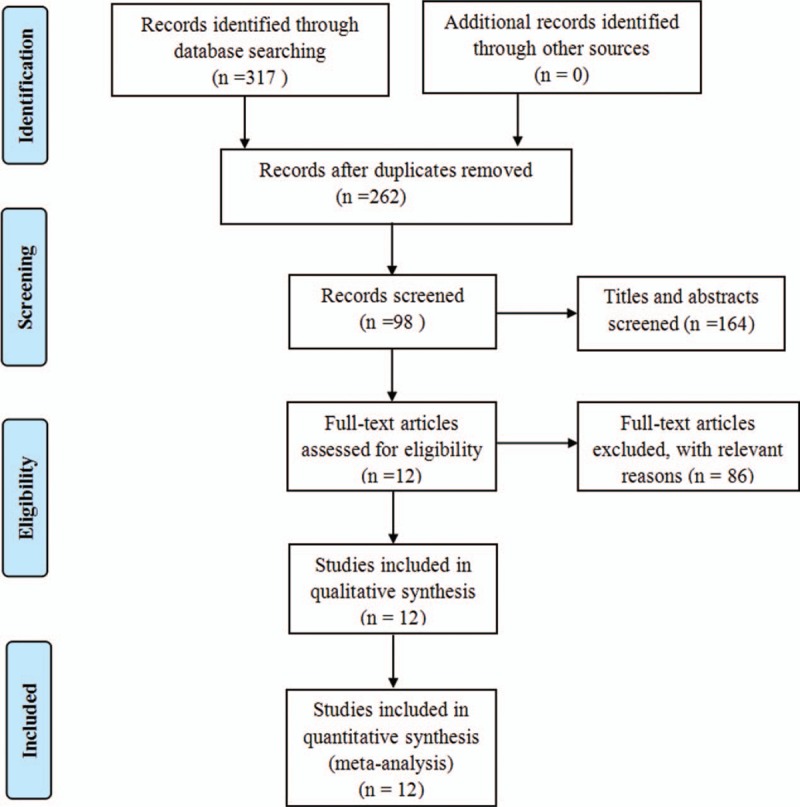

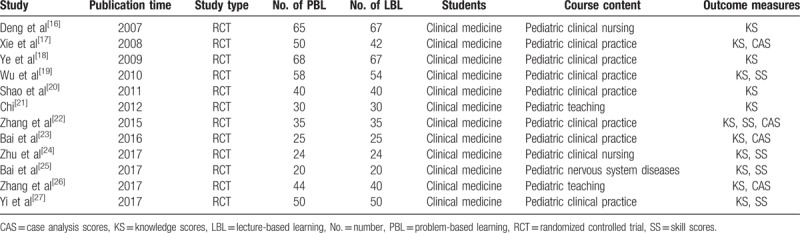

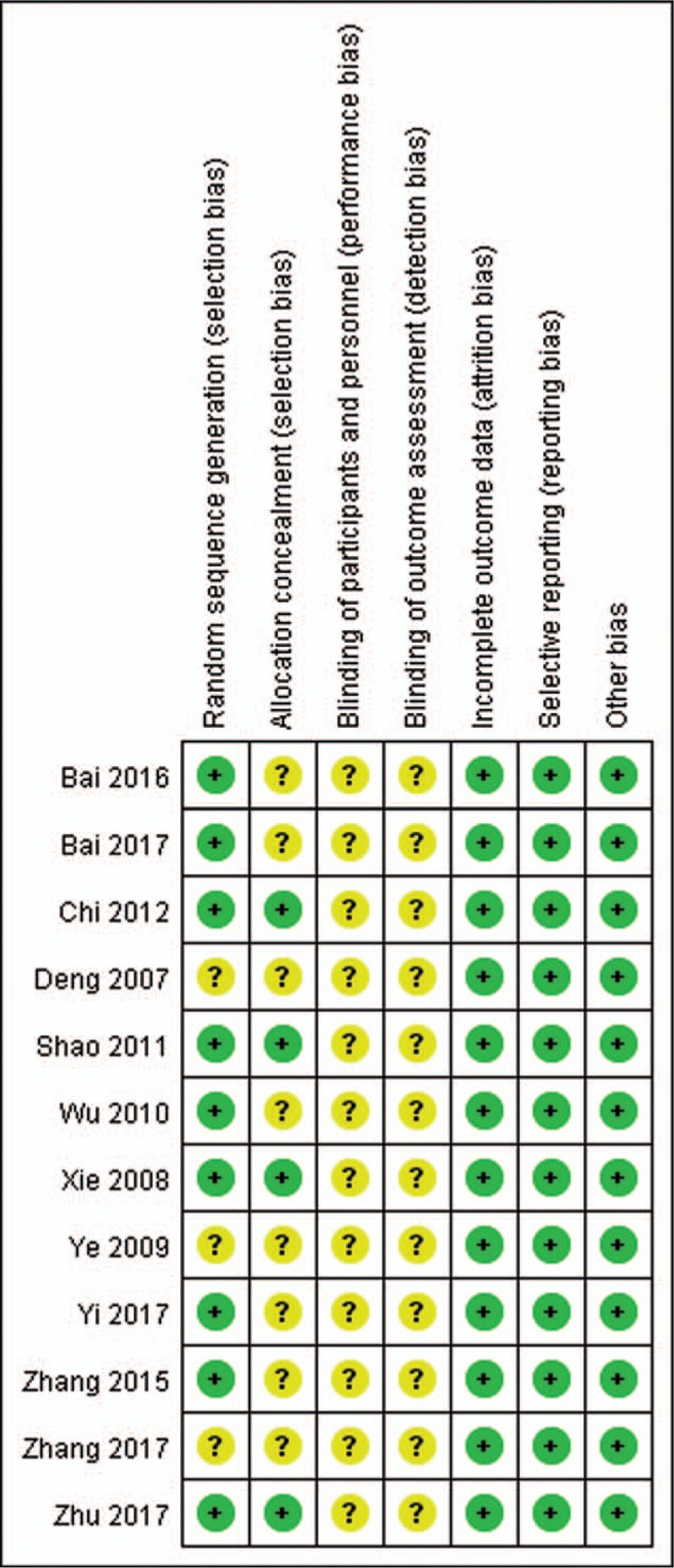

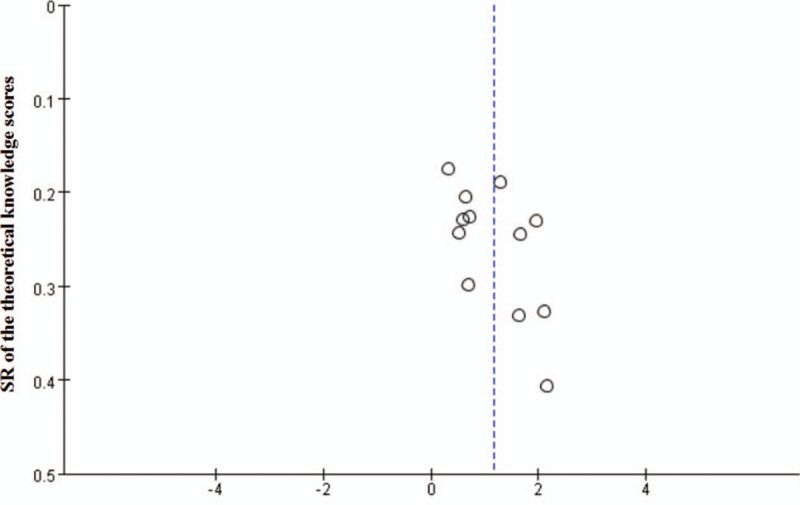

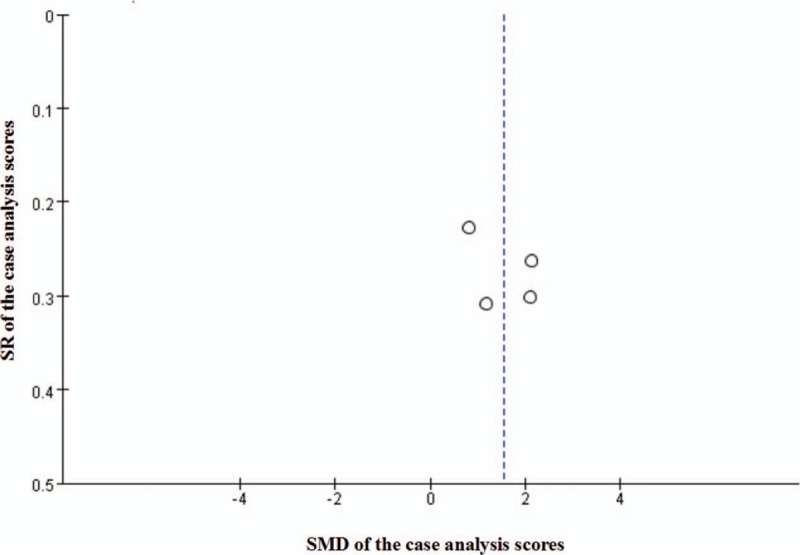

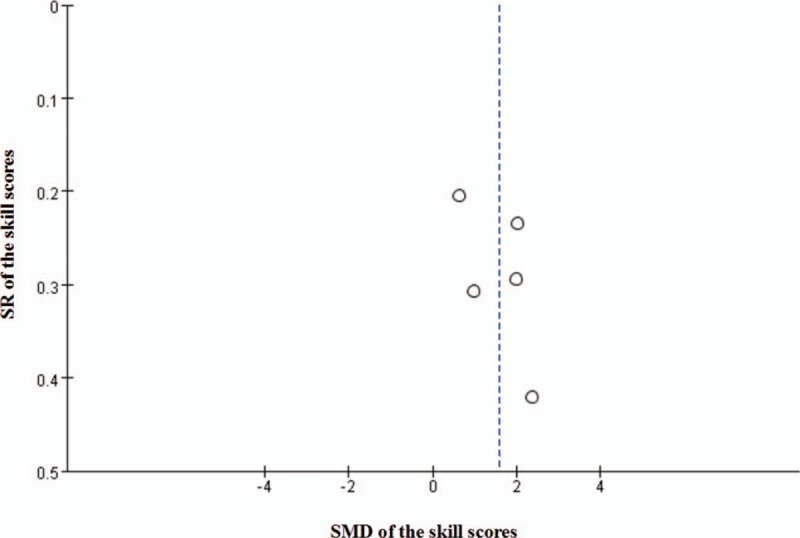

The flow chart of the study inclusion and exclusion criteria is shown in Figure 1. In total, 317 potentially relevant studies were identified. At the screening stage, 305 studies were excluded, since they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Thus, a total of 12 RCTs,[16–27] including 1003 medical students, were included in the meta-analysis. The analysis included 509 students in the PBL group and 494 students in the LBL group. Sample sizes ranged from 20 to 68. All of the included studies were published between 2007 and 2017. The types of courses included 2 courses[21,26] on pediatric teaching, 1 course[25] on pediatric nervous system diseases, and 7 courses[16–24,27] on pediatric clinical practice. The scores on the pediatric knowledge examination were used to assess the students’ mastery of the related theoretical knowledge, and the scores on the pediatric skill and case analysis tests were used to evaluate the students’ clinical skills. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of all of the included studies. Figure 2 shows the risk of bias assessment of the 12 included studies. Nine studies described the methods of the random sequences in detail,[17,19,20–25,27] but the other 3 studies’ methods[16,18,26] were unclear. All studies reported any incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other biases. The allocation concealment and blinding methods were not stated in these studies. The meta-analysis independently used funnel plots of the theoretical knowledge, skill, and case analysis scores to assess any publication bias; the plots were generally symmetrical and suggested a low publication bias (Figs. 3–5).

Figure 1.

Search strategy for the flow diagram.

Table 1.

The detailed baseline characteristics of all included studies.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias included in the randomized controlled trials. +, low risk of bias; ?, unclear risk of bias.

Figure 3.

Funnel plot analysis of theoretical knowledge scores for the potential publication bias in the meta-analysis. SMD = standardized mean difference, SR = standard error.

Figure 5.

Funnel plot analysis of case analysis scores for the potential publication bias in the meta-analysis. SMD = standardized mean difference, SR = standard error.

Figure 4.

Funnel plot analysis of theoretical skill scores for the potential publication bias in the meta-analysis. SMD = standardized mean difference, SR = standard error.

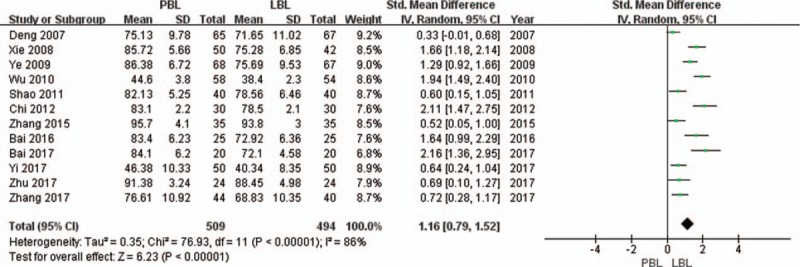

3.2. Meta-analysis of theoretical knowledge scores

All of the included studies[16–27] reported relevant data on the theoretical knowledge scores (509 and 494 students in the PBL and LBL groups, respectively). The meta-analysis of the theoretical knowledge scores found that the PBL teaching model significantly increased theoretical knowledge scores by a mean of 1.16 compared to those of the LBL teaching model (95% CI, 0.79–1.52; P < .00001). The random effects model was used for the meta-analysis because of a high level of heterogeneity (P < .00001, I2 = 86%) (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Analyses conducted by random effects model. Interstudy heterogeneity was tested by the Cochran Q statistic (χ2) at a significance level of P < .1. The meta-analysis of the theoretical knowledge scores found that the problem-based learning (PBL) teaching model significantly increased theoretical knowledge scores compared to those of the lecture-based learning (LBL) teaching model.

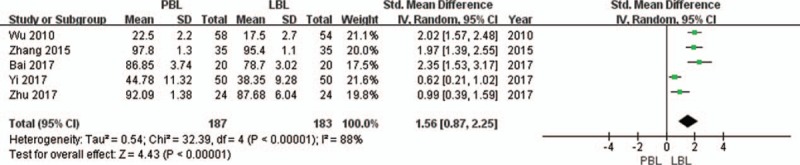

3.3. Meta-analysis of skill scores

A total of 5 studies[19,22,24,25,27] reported relevant data on skill scores (187 and 183 students in the PBL and LBL groups, respectively). The meta-analysis of the skill scores found that the PBL teaching model significantly increased skill scores by a mean of 1.56 compared with those of the LBL teaching model (95% CI, 0.87–2.25; P < .00001). The random effects model was used for the meta-analysis because of a high level of heterogeneity (P < .00001, I2 = 88%) (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Analyses conducted by random effects model. Interstudy heterogeneity was tested by the Cochran Q statistic (χ2) at a significance level of P < .1. The meta-analysis of the skill scores found that the problem-based learning (PBL) teaching model significantly increased skill scores compared with those of the lecture-based learning (LBL) teaching model.

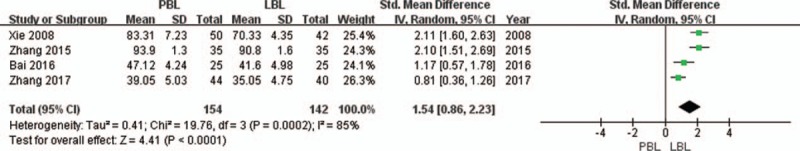

3.4. Meta-analysis of case analysis scores

A total of 4 studies[17,22,23,26] reported relevant data on case analysis scores (154 and 142 students in the PBL and LBL groups, respectively). The meta-analysis of the case analysis scores found that the PBL teaching model significantly increased case analysis scores by a mean of 1.54 compared with the LBL teaching model (95% CI, 0.86–2.23; P < .00001). The random effects model was used for the meta-analysis because of a high level of heterogeneity (P = .0002, I2 = 85%) (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Analyses conducted by random effects model. Interstudy heterogeneity was tested by the Cochran Q statistic (χ2) at a significance level of P < .1. The meta-analysis of the case analysis scores found that the problem-based learning (PBL) teaching model significantly increased case analysis scores compared with the lecture-based learning (LBL) teaching model.

4. Discussion

The PBL is a student-centered teaching model, which has been widely used in various medical education programs.[28,29] However, considering the different educational system and cultural background in China, the effectiveness of the PBL teaching method might be affected, so there is controversy regarding its use in China. As far as we know, there are very few studies that have assessed the role of PBL in pediatric medical education. Therefore, we performed the current meta-analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of the PBL teaching model in pediatric medical education in China.

The main finding of the meta-analysis was that the PBL teaching model significantly increased theoretical knowledge scores by a mean of 1.16, skill scores by a mean of 1.56, and case analysis scores by a mean of 1.54 when compared with those of the LBL teaching model. This is consistent with recent PBL studies in pharmaceutical[30,31] and dental education[32,33] in China. In clinical practice, the traditional teaching method sees the teacher as the core, while the student can only passively acquire the knowledge; the students might experience a lack of enthusiasm and doubt the doctors’ sense of responsibility. By introducing the PBL teaching method into clinical practice teaching, through reasoning, analyzing and applying their knowledge, students achieve the learning tasks of self-study, reasoning, and knowledge application abilities. On the contrary, the new teaching model also urges teachers to master the latest information and scientific research results. Therefore, the students’ basic knowledge and clinical skills are greatly improved, as well as their communication ability. However, PBL teaching has put forward higher requirements for teachers, especially in the writing of medical records, which not only requires teachers’ professional knowledge but also requires higher comprehensive literacy, as well as different teaching objectives. It is necessary to organize the various contents of medical records and to train the teaching doctors accordingly. For example, if PBL teaching is carried out in a theoretical course, it is necessary to integrate the medical curriculum. Therefore, the growth potential of the PBL teaching model in China depends on more enthusiastic teachers’ participation, and there is still much research to be done in China.

Some studies have even reported that PBL has had a negative impact on knowledge examinations due to difficulty acquiring factual knowledge.[9,10] There are some possible reasons why the results are inconsistent. First, it is necessary to take into account the differences in higher medical education between China and the Western countries. The PBL teaching model is a new teaching model for most Chinese students, since they have not received this kind of education since the beginning of primary school.[17,19] PBL teaching methods are more likely to stimulate their interest in learning and to contribute to the process of knowledge acquisition.[21,22] Second, pediatric medicine is a very practical subject. Clinical learning is the starting point for medical students to enter clinical practice and the bridge between theory and practice. It plays the role of connecting the past and the future in medical education. However, the way in which to train qualified clinicians is a problem that has been considered and explored in clinical teaching. The PBL model is a kind of heuristic model between the student-centered and teacher-oriented methods, which is different from the traditional teaching model.[2,19,23] By using PBL teaching, students can better receive clinical thinking training at the initial stage of their specialized clinical courses, and the whole teaching process becomes a process of students’ knowledge seeking and discovery.

Despite the rapid development of medical technology, basic clinical skills, such as theoretical knowledge, physical examination, and case analysis, are still the most important and effective tools for the diagnosis of diseases. Therefore, the development of these skills in pediatric medical education is essential for medical students. According to our findings, PBL has a strong positive impact on students’ skill performance. The most important aspects of pediatric medical education is to cultivate students’ clinical diagnostic skills and ability to solve clinical problems. Therefore, compared with traditional teaching methods, PBL has more obvious advantages in clinical teaching. The results of this meta-analysis are consistent with previous findings that PBL can effectively improve clinical skills. Wang et al[13] performed a meta-analysis with a total of 2086 medical students, which suggested that PBL seems to be more effective in improving knowledge and skills than traditional teaching methods used in physical diagnostics education in China. These results encourage Chinese educators to find new teaching models, including the PBL teaching model, to improve medical students’ performance and clinical skills.

The reasons behind these trends are very simple. In the early years, studies showed that students who received a PBL medical education had definitively better scores on theoretical knowledge and clinical skills than students who received a traditional medical education.[4,13,18] Although PBL shows many benefits, it is difficult to apply PBL widely in Chinese pediatric medical education. First, the PBL teaching method requires a long time commitment for students.[34] Second, in the early stages of PBL teaching, students may lack systematic and in-depth theoretical knowledge and focus on problem solving. Therefore, students may be unable to organize and master the internal logical structure of the knowledge, which may increase learning difficulties. Different from the Western countries, Chinese students have long accepted the traditional teaching model, which is considered to be sufficient for accumulating theoretical knowledge. Third, although China has become the world's economic leader, its fast-growing education system is tasked with creating enough medical professionals to care for nearly 20% of the world's population. However, a majority of universities think they do not have enough faculty to teach PBL and that the PBL teaching model takes a long time. Moreover, some universities are not using PBL currently because of a lack of financial and faculty resources.[9] Given the above reasons, this may affect the promotion and application of PBL.

In the current meta-analysis, there is also high heterogeneity in the results of the theoretical knowledge, skill, and case study scores, which may be due to the following factors. First, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are widely believed to provide the highest level of evidence for the effectiveness of intervention. However, it is not always possible to use very strict RCTs in medical education. Although most of the studies in this meta-analysis were designed as RCTs, there were still 3 studies that did not describe their methods for random sequence generation, and none of them described the allocation concealment or blinding methods. Consequently, the methodologic qualities of the methods were not high in this meta-analysis. Second, the definition and implementation of PBL teaching are closely related to the quality of medical education, the ability of the educator, and the cultural background of the medical students in China, and these factors may cause significant differences in the effect of PBL implementation. Third, there are no uniform criteria for assessing the effectiveness of PBL on knowledge and skills.

There are some limitations to the present study. First, there were only Chinese medical students included in this study, which suggests the results may be more suitable for Chinese and Asian medicine education than Western medicine education. Therefore, the results of this meta-analysis may have limited geographical generalization. Second, the present study was based on only 12 RCTs with 1003 medical students in pediatric medical education in China up to June 2018, so the sample size was relatively small in this meta-analysis. Thus, a greater number of high-quality RCTs are needed to confirm the above conclusions. Third, a subgroup analysis was not performed based on the different types of courses, because the analysis was limited by incomplete data. Fourth, the methodologic quality of this study on the effectiveness of PBL in Chinese pediatric medical education is generally low, and the results are heterogeneous.

5. Conclusion

The current meta-analysis shows that PBL in pediatric medical education in China appears to be more advantageous than the traditional teaching method in improving theoretical knowledge, skill, and case analysis scores. However, a more controlled design of RCT is needed to confirm the above conclusions in future work.

Author contributions

Data curation: Xiaoxi Lu.

Formal analysis: Yimei Ma.

Investigation: Yimei Ma.

Methodology: Xiaoxi Lu.

Software: Yimei Ma.

Supervision: Yimei Ma, Xiaoxi Lu.

Writing – original draft: Yimei Ma, Xiaoxi Lu.

Writing – review & editing: Yimei Ma, Xiaoxi Lu.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval, LBL = lecture-based learning, PBL = problem-based learning, RCTs = randomized controlled trials, SMD = standardized mean difference.

The study was supported by the Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province (2017FZ0056).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Thurley P, Dennick R. Problem-based learning and radiology. Clin Radiol 2008;63:623–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].McParland M, Noble LM, Livingston G. The effectiveness of problem-based learning compared with traditionalteaching in undergraduate psychiatry. Med Educ 2004;38:859–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Subramaniam R. Problem-based learning: concept, theories, effectiveness and application to radiology teaching. Australas Radiol 2006;50:339–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Holen A, Manandhar K, Pant DS, et al. Medical students’ preferences for problem-based learning in relation to culture and personality: a multicultural study. Int J Med Educ 2015;6:84–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].O Doherty D, Mc Keague H, Harney S, et al. What can we learn from problem-based learning tutors at a graduate entry medical school? A mixed method approach. BMC Med Educ 2018;18:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].De Grave WS, Dolmans DHJM, Van Der Vleuten CPM. Profiles of effective tutors in problem-based learning: scaffolding student learning. Med Educ 1999;33:901–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Clarke CE. Problem-based learning: how do the outcomes compare with traditional teaching. Br J Gen Pract 2006;56:722–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Maudsley G. Making sense of trying not to teach: an interview study of tutors’ ideas of problem-based learning. Acad Med 2002;7:162–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Colliver JA. Effectiveness of problem-based learning curriculum: research and theory. Acad Med 2000;75:259–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Distlehorst LH, Dawson E, Robbs RS, et al. Problem-based learning outcomes: the glass half-full. Acad Med 2005;80:294–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kliegman RM, Stanton BMD, Geme JS, et al. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. The United States of America: Elsevier Medicine 2011;6:1. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Prescott WA, Jr, Dahl EM, Hutchinson DJ. Education in pediatrics in US colleges and schools of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ 2014;78:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wang J, Xu Y, Liu X, et al. Assessing the effectiveness of problem-based learning in physical diagnostics education in China: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2016;6:36279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Deng HZ, Dong YS, Chen YF, et al. Study on problem-based learning (PBL) as teaching reform in clinical clerkship in pediatrics [in Chinese]. China Higher Med Educ 2007;2:16–7. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Xie Y, Yang ZZ, Chai BC. Application of problem-based learning (PBL) in clinical teaching in pediatrics [in Chinese]. China Higher Med Educ 2008;12:18–9. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ye LP, Li CC, Luo YC, et al. Comparative study on problem-based learning (PBL) and lecture-based learning (LBL) of clinical teaching in pediatrics [in Chinese]. China Higher Med Educ 2009;4:103–4. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wu JL, Mu DZ, Xiong Y. The application of problem based learning in clinical practice for foreign students in neonatal department [in Chinese]. Res Med Educ 2010;9:97–9. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Shao QL, Yao L, Zhao XX. The study and application of PBL in the pediatric clinical practice [in Chinese]. Chin Foreign Med Res 2011;24:167–8. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chi MZ. Exploration in optimizing the pediatric teaching by PBL teaching method [in Chinese]. Northwest Med Educ 2012;5:1015–7. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zhang H, Wang BZ, Kuang Q, et al. PBL teaching mode in the practical teaching effect in clinical pediatrics [in Chinese]. China J Pharmaceutical Econ 2015;3:125–6. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bai XL, Zhang JH, Gong LL. The application of PBL in clinical practice of pediatrics [in Chinese]. China Continuing Med Educ 2016;6:8–9. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zhu XM, Qiu JJ, Li FM, et al. The application of PBL teaching method in pediatric clinical nursing effect assessment [in Chinese]. Harbin Med J 2017;3:265–6. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bai XL, Yi NL, Zhang JH. Application of PBL teaching approach in clinical internship of nervous system diseases [in Chinese]. Contemporary Med 2017;6:179–80. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zhang CY, Liu YF, Gao XL, et al. Using PBL in pediatric preceptorship and evaluating its effects [in Chinese]. China Higher Med Educ 2017;11:120–1. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Yi XL, Li XL, Jiang Y. Application of PBL teaching mode in standardized training of pediatric dwellers [in Chinese]. J Qiqihar Univ Med 2017;16:1936–7. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Blake RL, Hosokawa MC, Riley SL. Student performances on Step 1 and Step 2 of the United States Medical Licensing Examination following implementation of a problem-based learning curriculum. Acad Med 2000;75:66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hoffman K, Hosokawa M, Blake RJ, et al. Problembased learning outcomes: ten years of experience at the University of Missouri-Columbia School of Medicine. Acad Med 2006;81:617–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wright D, Wickham J, Sach T. Problem-based learning: an exploration of student opinions on its educational role in one UK pharmacy undergraduate curriculum. Int J Pharm Pract 2014;22:223–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Azu OO, Osinubi AA. A survey of problem-based learning and traditional methods of teaching anatomy to 200 level pharmacy students of the University of Lagos, Nigeria. Afr J Pharm Pharmacol 2011;5:219–24. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bassir SH, Sadr-Eshkevari P, Amirikhorheh S, et al. Problem-based learning in dental education: a systematic review of the literature. J Dent Educ 2014;78:98–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Montero J, Dib A, Guadilla Y, et al. Dental students’ perceived clinical competence in prosthodontics: comparison of traditional and problem-based learning methodologies. J Dent Educ 2018;82:152–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Fan AP, Kosik RO, Tsai TC, et al. A snapshot of the status of problem-based learning (PBL) in Chinese medical schools. Med Teach 2014;36:615–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]