Abstract

Advancements in genetic testing now allow early identification of previously unresolved neuromuscular phenotypes. To illustrate this, we here present diagnoses of glycogen storage disease IV (GSD IV) in two patients with hypotonia and delayed development of gross motor skills. Patient 1 was diagnosed with congenital myopathy based on a muscle biopsy at the age of 6 years. The genetic cause of his disorder (two compound heterozygous missense mutations in GBE1 (c.[760A>G] p.[Thr254Ala] and c.[1063C>T] p.[Arg355Cys])), however, was only identified at the age of 17, after panel sequencing of 314 genes associated with neuromuscular disorders. Thanks to the availability of next-generation sequencing, patient 2 was diagnosed before the age of 2 with two compound heterozygous mutations in GBE1 (c.[691+2T>C] (splice donor variant) and the same c.[760A>G] p.[Thr254Ala] mutation as patient 1). GSD IV is an autosomal recessive metabolic disorder with a broad and expanding clinical spectrum, which hampers targeted diagnostics. The current cases illustrate the value of novel genetic testing for rare genetic disorders with neuromuscular phenotypes, especially in case of clinical heterogeneity. We argue that genetic testing by gene panels or whole exome sequencing should be considered early in the diagnostic procedure of unresolved neuromuscular disorders.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this chapter (10.1007/8904_2018_148) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Congenital myopathy, Gene panel, Genetic testing, Glycogen storage disease IV, Hypotonia

Introduction

Rapidly evolving genetic diagnostic procedures provide a powerful tool to unravel the disease cause in pediatric patients with a suspected genetic disorder. Specifically, this advancement allows identification of mild or atypical phenotypes of rare Mendelian diseases (Choi et al. 2009). Our recent identification of glycogen storage disease type IV (GSD IV) [OMIM 232500] in two patients with congenital myopathy serves as a good example.

GSD IV is an autosomal recessive inborn error of metabolism caused by mutations in the gene-encoding glycogen-branching enzyme (GBE1, EC 2.4.1.18). This enzyme is critical for the production of normal glycogen. Reduced activity causes linear glycogen with long chains of glucose and infrequent branch points. The resulting amylopectin-like polysaccharide (polyglucosan) accumulates in all tissues, most notably in liver and muscle. The GSD IV phenotype represents a heterogeneous continuum of disease that ranges from perinatal, early fatal neuromuscular disease, to severe isolated hepatopathy requiring liver transplantation, to mild myopathy (Moses and Parvari 2002; Magoulas and El-Hattab 2013). Adult polyglucosan body disease (APBD), characterized by progressive dysfunction of central and peripheral nervous system in adulthood, is caused by mutations in the same gene (Klein 2013).

The two patients described here both presented with hypotonia, delayed development of gross motor skills, and mild failure to thrive. The “diagnostic odyssey” of patient 1 was long and only ended after the advent of next-generation sequencing when he was aged 17. In contrast, the genetic defect in patient 2 was identified within the first 2 years of life, illustrating the advancement of genetic diagnostics in patients with unresolved neuromuscular phenotypes.

Case Report

Case Description 1

After a normal pregnancy and delivery, patient 1 (male) was born to nonconsanguineous parents and presented with late development of gross motor skills. Neck holding, crawling, and standing were all delayed by several months. Fine motor, cognitive, and verbal development were normal. Clinically, he showed weakness and hypotrophy of all large muscles. No sensory, pyramidal, or cerebellar deficits were present and motor nerve conduction was normal. Creatine kinase was always in the normal range (80–160 U/L) and no abnormalities in the DMPK gene were found. At age 6 years, a muscle biopsy showed mild fiber-type disproportion without any signs pointing towards a more specific disorder, such as (polyglucosan) inclusion bodies. At 7 years of age, his growth was stunted with length 114 cm (−2 SD) and weight-to-length ratio 16 kg/114 cm (−2.4 SD). At age 8, mild hepatomegaly was noticed (1–2 cm below costal margin), liver transaminases were mildly increased (ALP max 219 U/L, AST max 116 U/L, and ALT max 73 U/L), and prolonged overnight fasting caused symptoms compatible with hypoglycemia. Indeed, a regular fasting test showed diminished fasting tolerance (blood glucose <3.0 mmol/L after 15 h).

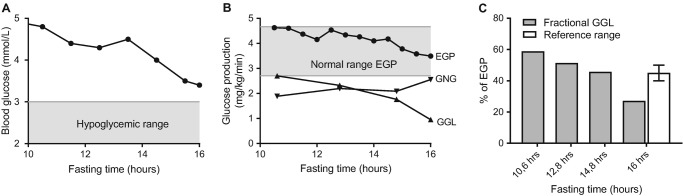

To further investigate the nature of this intolerance, a fasting test with use of stable isotopes was performed at age 9 in which blood glucose was 3.4 mmol/L after 16 h of fasting (Fig. 1a). Endogenous glucose production (EGP) remained within the normal range, but the fractional glycogenolysis (GGL) was lower than the reported fractional GGL for healthy controls (Fig. 1b, also see Supplementary Material). Lacking an exact, genetic explanation for this glycogenolytic deficiency, a functional diet approach was started that aimed at preventing catabolism and consisted of three large meals, frequent smaller meals, and an evening dose of raw cornstarch (40 g). This diet led to compensatory growth, normalization of gross motor skills, and improvement of exercise tolerance. He was able to cycle 22 km each day, but still experienced exhaustion at the end of the day. At age 17, another fasting test was performed to assess the safety of extended fasting given his intention to live independently in student housing. During the fasting test glucose concentration now remained above 4.5 mmol/L after 17 h of fasting. This initiated a new diagnostic work-up, including next generations sequencing which by then had become available and affordable.

Fig. 1.

Glucose kinetics during a fasting test in patient 1, including (a) plasma glucose concentrations, (b) endogenous glucose production (EGP; circle), glycogenolysis (GGL; triangle), and gluconeogenesis (GNG; inverted triangle), and (c) fractional glycogenolysis in relation to the fasting time

Genetic Evaluation

Genetic investigation of 314 genes associated with neuromuscular disorders revealed two compound heterozygous missense mutations in the GBE1 gene (NM_00158.3): c.[760A>G] p.[Thr254Ala] (previously reported, Said et al. 2016) and c.[1063C>T] p.[Arg355Cys] (previously unreported). Three pathogenicity prediction algorithms (PolyPhen-2: both damaging, MutationAssesor: T253A = medium impact, R355C = high impact, MutationTaster2: both disease causing) predicted T254A to have medium impact and R355C to have high impact on protein function. The activity of GBE1 in white blood cells was severely impaired compared to reference values. The muscle biopsy taken at age 6 was re-examined, but no polyglucosan bodies, which could have been diagnostic for GSD IV, could be identified.

Radiographic Evaluation

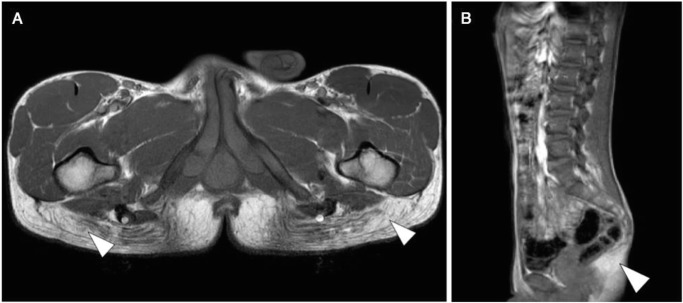

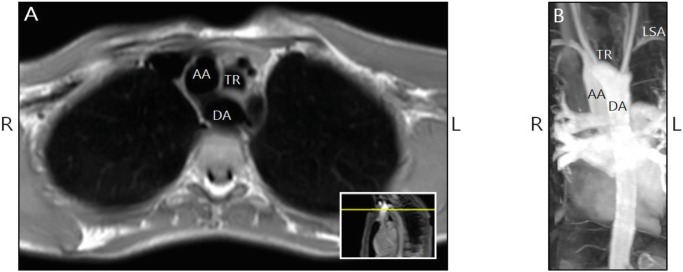

To further investigate the muscular phenotype, we performed a whole body MRI scan at age 17. This scan showed bilateral atrophy of the gluteus maximus muscle and mild atrophy of the semimembranosus muscle (Fig. 2). The muscle MRIs showed no edema, diffusion restriction, or other signs of active myositis. All other muscles were preserved. Echocardiography showed no cardiomyopathy. MR-angiography (MRA) did reveal a double aortic arch with a dominant right-sided arch and an incomplete left-sided arch (Fig. 3). At present he is a student and doing well.

Fig. 2.

T1-weighted MR images of patient 1 at age 17. The transverse section of the pelvis (a) and the sagittal section of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis (b) demonstrated nearly complete bilateral replacement of the normal hypo-intense signal of gluteus maximus muscle with the hyperintense signal of fat (white arrowheads)

Fig. 3.

Transverse MRI (a) and coronal MRI-angiography (b) in patient 1 showed a dominant right aortic arch and Kommerell diverticulum. The left subclavian artery (LSA) was not directly connected to the Kommerell diverticulum. Most likely an atypical duct previously connected the Kommerell diverticulum to the LSA. TR trachea, AA ascending aorta, DA descending aorta

Case Description 2

After normal pregnancy and delivery, patient 2 (male) was born to nonconsanguineous parents and presented at the age of 6 months with hypotonia. Despite physiotherapy, development of gross motor skills, including free sitting and standing, was delayed by several months. At the age of 17 months, occult spina bifida was noted, but no spinal cord abnormalities were seen on MRI. At 21 months, physical examination showed a length of 85 cm (−0.3 SD), a weight-to-length ratio of 10.6 kg/85 cm (−1.8 SD), and a head circumference of 49.3 cm (0 SD), notably underdeveloped musculature of all four limbs with mild hypotonia, externally rotated gait, and lumbar hyperlordosis. Creatine kinase (199 U/I) and aspartate transaminase (AST 64 U/I) levels were mildly elevated, while other liver enzymes remained within the reference range (ALT <40 U/I, LDH <400 U/L, and AP <300 U/L). Abdominal ultrasound did not show hepatosplenomegaly and musculoskeletal ultrasound, nerve conduction studies, and cardiac tests did not reveal abnormalities. The clinical presentation of generalized muscle atrophy without evident liver involvement had a wide differential diagnosis. It was most suspicious for selenoprotein-related myopathy, for which muscle biopsies are often inconclusive. Therefore, a gene panel investigation into a broader range of disorders was performed.

Genetic and Enzymatic Evaluation

Investigation of 74 genes associated with distal myopathies revealed two missense mutations in the GBE1 gene: c.[691+2T>C] splice donor variant (previously reported as pathogenic variant in severe GSD IV, Fernandez et al. 2010) and the same mutation as patient 1; c.[760A>G] p.[Thr254Ala] (previously reported, Said et al. 2016). As mentioned above, three pathogenicity prediction algorithms predicted T254A to be a disease-causing variant. The activity of GBE1 in red and white blood cells was severely reduced (5–10% of normal). No muscle biopsy was performed because genetic and enzymatic methods had already confirmed the diagnosis. Although laboratory and radiological findings did not suggest liver involvement, a continuous glucose monitoring was performed to rule out the possibility of unnoticed hypoglycemia. No hypoglycemic events occurred during 34 h, and glucose levels remained above 3.7 mmol/L during an 8-h overnight fast. At present, the patient is aged 3 years, no hypoglycemic events have occurred thus far, and he receives a normal diet. He still suffers from hypotonia, but motor skill development progresses, CK (148 U/L) and AST (35 U/L) values remain within the reference range, and weight-to-length ratio normalizes (15.7 kg/103.8 cm, −0.95 SD).

Discussion

GSD IV is an autosomal recessive metabolic disorder, with an incidence of 1:600,000–1:800,000. Classically, five clinical subtypes have been recognized. However, the widely heterogeneous presentations, varying in age of onset and affected organ systems, do not all fit well into these subtypes (Burrow et al. 2006). The patients here described presented with generalized hypotonia and myopathy and could be classified as presentations of the childhood neuromuscular subtype (Magoulas and El-Hattab 2013) with little (patient 1) to no (patient 2) involvement of the liver and a mild clinical course. However, fasting intolerance and decreased glycogenolytic capacity as observed and quantified in patient 1 have not been reported previously in this subtype. Indeed, hypoglycemia is rarely observed in GSD IV and only in the context of liver failure. This shows that the clinical spectrum of GSD IV is ever expanding and will likely further expand in the current age of genetic testing.

The severity of GSD IV phenotypes has been correlated to residual glycogen-branching enzyme activity, with null mutations leading to severe perinatal and congenital subtypes. However, it remains largely unclear how milder, biallelic mutations relate to organ involvement and disease progression (Magoulas and El-Hattab 2013). The c.[1063C>T]; p.[Arg355Cys] missense mutation identified in patient 1 has not been reported previously. It concerns a highly conserved (Fig. S1 in Supplementary Material) arginine residue located in the catalytic core and has high predicted impact on protein function. The c.[691+2T>C] mutation identified in patient 2 affects a consensus splicing site and was previously described in a patient with congenital neuromuscular subtype and 20% residual enzyme activity in fibroblasts (Fernandez et al. 2010). The c.[760A>G] p.[Thr254Ala] mutation found in both our patients has recently been identified in one other patient with a mild classic hepatic subtype and >25% residual enzyme activity in fibroblasts (Said et al. 2016). When compared to these patients with similar genotypes, residual enzyme activity in our patients (patient 1: undetectable; patient 2: 5–10%) was remarkably low. Besides, patients reported in the literature with comparable childhood neuromuscular phenotypes typically had >10% residual activity in fibroblasts (Magoulas et al. 2012). This discrepancy might well be caused by the use of blood cells in our enzyme activity tests versus fibroblasts in most other reports, as residual activity can vary between cell types within the same individual (Li et al. 2010). In summary, both our patients with predominant muscular phenotypes have one unique mutation that has high predicted impact on protein function and share the milder c.[760A>G] p.[Thr254Ala] mutation previously identified in a patient with a predominant hepatic phenotype. This shows that it remains difficult to predict organ involvement based on genotype alone and suggests that other genetic or environmental factors also play a role.

The muscle MRI of patient 1 showed replacement of muscle with connective and adipose tissue in the gluteus maximus muscles. Although cardiomyopathy is a common finding in GSD IV, echocardiographic evaluation of our patient did not reveal this. However, MRA showed a double aortic arch, an unusual finding in the general population (estimated incidence 1:1,000–1:10,000). The co-occurrence of double aortic arch and GSD IV could be coincidental, but indications exist that GBE1 mutations can modify structural cardiac development. First, Lee et al. (2011) showed abnormal cardiac development in a GBE1 −/− mouse model. Second, double aortic arch has been reported in other storage disorders, including GSD II (Akalin et al. 2000) and mucopolysaccharidosis (Slepov and Chumakov 1997). Further investigations are needed into the possible correlation between GBE1 mutations and structural cardiac abnormalities and into the possibility of these two conditions co-existing, independent of each other.

No polyglucosan bodies or other histopathological findings suggestive of GSD IV could be identified in the muscle biopsy of patient 1, even upon re-examination after the genetic diagnosis. A review of the literature revealed that the absence of polyglucosan bodies in biopsies from patients with GBE1 dysfunction is very rare (Supplementary Table 2 in Supplementary Material). Out of 60 patients with GSD IV, only 1 patient did not have histopathological findings indicative of abnormal glycogen storage. Upon intensive re-examination of this patient’s muscle biopsy after genetic diagnosis, sporadic polyglucosan bodies could be identified (Ravenscroft et al. 2013). Out of 24 patients with adult polyglucosan body disease, two patients did not have polyglucosan bodies in muscle biopsies (Colombo et al. 2015). Importantly, the literature might underestimate the percentage of GSD IV patients without polyglucosan bodies, because histopathological findings are key to the diagnosis when no (untargeted) genetic methods are available.

In conclusion, we present two patients with a similar neuromuscular presentation of GSD IV but with strikingly different diagnostic gaps: 17 years in patient 1 and 2 years in patient 2. Their cases illustrate the value of early genetic testing for rare genetic disorders. Genetic testing was especially helpful in patient 1, in which typical histopathological findings were absent from the muscle biopsy. However, genetic testing does have limitations including (1) false negatives due to low sequencing coverage or exclusion of disease-causing regions and (2) diagnostic dilemmas arising from variants of uncertain significance (Reid et al. 2016). Therefore, genetic testing should always be preceded by a thorough clinical workup and complemented by biochemical evaluations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

■ (DOCX 228 kb)

Synopsis

Our recent diagnoses of GSD IV in two patients with hypotonia and delayed development of gross motor skills further expand the clinical phenotype of GSD IV and demonstrate the value of early genetic testing in the diagnostic procedure of unresolved neuromuscular disorders.

Details of the Contributions of Individual Authors

IFS and GV drafted the manuscript and designed the figures with support of SF GV is the metabolic pediatrician of patient 1. GCK is the pediatric neurologist of patient 2. HHH interpreted the stable isotope fasting test in patient 1. LP is the clinical neurologist of patient 1. DD executed the genetic diagnostics in patient 1. JMPJB is the pediatric cardiologist who interpreted the echocardiography and MRI-angiography in patient 1. SB executed the genetic diagnostics in patient 2. All authors revised the manuscript.

Competing Interest Statement

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Approval and Patient Consent Statement

No ethics approval or patient consent was required for the presented findings.

Contributor Information

Saskia Biskup, Email: Saskia.Biskup@humangenetik-tuebingen.de.

Gepke Visser, Email: G.Visser-4@umcutrecht.nl.

References

- Akalin F, Alper G, Oztunç F, Kotiloğlu E, Turan S. A case of glycogen storage disease type II with double aortic arch. Acta Paediatr. 2000;89(7):884–886. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2000.tb00399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrow TA, Hopkin RJ, Bove KE, et al. Non-lethal congenital hypotonia due to glycogen storage disease type IV. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:878–882. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi M, Scholl UI, Ji W. Genetic diagnosis by whole exome capture and massively parallel DNA sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(45):19096–19101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910672106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo I, Pagliarani S, Testolin S, et al. Adult polyglucosan body disease: clinical and histological heterogeneity of a large Italian family. Neuromuscul Disord. 2015;25:423–428. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez C, Halbert C, De Paula AM, et al. Non-lethal neonatal neuromuscular variant of glycogenosis type IV with novel GBE1 mutations. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41:269–271. doi: 10.1002/mus.21499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein CJ, et al. Adult polyglucosan body disease. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Fong CT, Smith RJ, et al., editors. GeneReviews. Seattle: University of Washington; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YC, Chang CJ, Bali D, Chen YT, Yan YT. Glycogen-branching enzyme deficiency leads to abnormal cardiac development: novel insights into glycogen storage disease IV. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20(3):455–456. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Chen C, Goldstein J, et al. Glycogen storage disease type IV: novel mutations and molecular characterization of a heterogeneous disorder. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2010;33(3):S83–S90. doi: 10.1007/s10545-009-9026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magoulas PL, El-Hattab AW, et al. Glycogen storage disease type IV. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Fong CT, Smith RJ, et al., editors. GeneReviews. Seattle: University of Washington; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magoulas PL, El-Hattab AW, Angshumoy R, Bali DS, Finegold MJ, Craigen WJ. Diffuse reticuloendothelial system involvement in type IV glycogen storage disease with a novel GBE1 mutation: a case report and review. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:943–951. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses SW, Parvari R. The variable presentations of glycogen storage disease type IV. Curr Mol Med. 2002;2(2):177–188. doi: 10.2174/1566524024605815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravenscroft G, Thompson EM, Todd EJ, et al. Whole exome sequencing in foetal akinesia expands the genotype-phenotype spectrum of GBE1 glycogen storage disease mutations. Neuromuscul Disord. 2013;23:165–169. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid ES, Papandreou A, Drury S, et al. Advantages and pitfalls of an extended gene panel for investigating complex neurometabolic phenotypes. Brain. 2016;139:2844–2854. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Said SM, Murphree MI, Mounajjed T, El-Youssef M, Zhang L. A novel GBE1 gene variant in a child with glycogen storage disease type IV. Hum Pathol. 2016;54:152–156. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2016.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slepov AK, Chumakov LF. Co-occurrence of double aortic arch with mucopolysaccharidosis in an infant. Klin Khir. 1997;7–8:105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

■ (DOCX 228 kb)