Abstract

Human oocyte maturation is a precondition for fertilization and ensuing embryonic development. Previously, we identified TUBB8 variants as a genetic determinant of human oocyte maturation arrest and showed that these variants cause variable and mixed phenotypes in oocyte maturation and early embryo development. We also estimated that rare inherited or de novo variants in the TUBB8 gene accounted for 30% of individuals in a small cohort of patients affected by oocyte maturation arrest. In the present study, we recruited a further 87 patients from unrelated families diagnosed with oocyte maturation or early embryonic arrest and identified 30 patients carrying TUBB8 variants. The corresponding phenotypes not only include oocyte maturation arrest, failure of fertilization, and early embryonic arrest, but also extend to the new phenotype of failure of embryo implantation. These observations provide the most detailed mutational and phenotypic spectrum of TUBB8, further extend the spectrum of variants and dysfunctional oocyte and embryo phenotypes caused by TUBB8 variants, and confirm previous findings for a critical role of TUBB8 during oocyte maturation and early embryonic development. Thus, TUBB8 mutation screening might not only be a genetic diagnostic marker for patients with oocyte maturation arrest, but might also have clinical implications for evaluating the competence of patients’ functional oocytes with first polar body (PB1).

Subject terms: Genetics research, Infertility

Introduction

Successful reproduction requires gamete maturation, fertilization, and early embryonic development. Oocyte maturation consists of a series of morphological and molecular changes, from germinal vesicle oocytes, to metaphase I oocytes, and finally to metaphase II oocytes [1–4]. Failure in any of the steps of oocyte maturation will lead to infertility [5].

In the early 1990s, the first cases of primary female infertility were diagnosed as oocyte maturation arrest after recurrent failure of in vitro fertilization (IVF)/intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) attempts [6]. Some similar cases were subsequently reported [7–10]. However, the molecular causes for the symptoms in these patients were unknown. TUBB8 is a highly conserved primate-specific β-tubulin isotype that is specifically expressed in oocytes and early embryos. Recently, we identified TUBB8 [MIM 616768] as the first disease-causing gene in oocyte arrest at the MI stage [11]. In subsequent studies, other variants in TUBB8 were identified by us and others [12–14], and a total of 26 different variants, including heterozygous/compound heterozygous missense variants, frameshift/non-frameshift deletions, and whole-gene deletions, were identified. It has also been estimated that variants in the TUBB8 gene might account for around 30% of patients with oocyte maturation arrest in a small cohort (n = 43) [12]. In addition, a few variants in TUBB8 show other phenotypes, such as failure of fertilization and early embryonic arrest [12, 13].

To further investigate the mutational and phenotypic spectrum of TUBB8 in female infertility, we sequenced exons of TUBB8 in a large cohort of female infertility patients with recurrent failure of IVF/ICSI characterized by problems with oocyte maturation, embryonic development, and implantation failure (n = 87). We identified 30 new patients with TUBB8 variants from unrelated families. In addition to the previously known phenotypes caused by TUBB8 variants, including oocyte maturation arrest, fertilization failure, and early embryonic arrest, we also observed the new phenotype of embryo implantation failure. These findings thus provide the most detailed mutational and phenotypic spectrum of TUBB8.

Methods

Human samples

Eighty-seven female infertility patients with recurrent failure of IVF and ICSI caused by abnormal development of oocytes and embryos were recruited from the Center of Reproductive Medicine, Shengjing Hospital, the Center of Reproductive Medicine, Shanghai Ninth Hospital affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University, and the Shanghai Ji Ai Genetics and IVF Institute. Peripheral blood was sampled for DNA extraction. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical College of Fudan University.

TUBB8 resequencing

Genomic DNA from patients and their family members was extracted from peripheral blood based on the previous protocol [11]. Four exons were amplified using specific primers [13]. Amplicons were then direct sequenced by Sanger sequencing, and the sequences were aligned to the reference sequence of TUBB8 (NM_177987.2, MIM 616768) with the CodonCode software to identify rare variants. The frequencies of the variants were analyzed using the ExAC database [15], and the functional effects of the variants were predicted by PolyPhen-2 [16] and PROVEAN [17, 18]. All variants identified were submitted to the LOVD v.3.0 (Leiden Open Variation Database, https://databases.lovd.nl/shared/genes/TUBB8) with patient IDs 168068,168080–168084,168086–168092, and 168094–168110.

Evaluation of oocyte and embryo phenotypes

Human oocytes were obtained from affected individuals and controls undergoing clinical IVF/ICSI. The morphologies of oocytes and embryos were examined by light microscopy, while the spindles of the oocytes were examined by polarization microscopy with an inverted microscope system (OLYMPUS IX71). Oocyte immunostaining was performed as previously described [13]. Briefly, oocytes were first fixed in 2.0% paraformaldehyde then incubated in membrane permeabilizing solution for 20 min and blocking buffer for 2 h. The oocyte spindles were stained with an anti-β-tubulin-FITC antibody (1:400 dilution, F2043, Sigma-Aldrich, US), while Hoechst 33342 (1:600 dilution, BD) was used to label DNA. Finally, images of oocytes were obtained on a confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP8, Germany)

Results

Mutational spectrum of TUBB8

We identified a total of 28 missense variants, 1 non-sense variant, and 3 frameshift insertion/in-frame deletion variants from 30 families, including 19 novel variants and 2 novel recurrent variants (c.292G>A; p.(G98R) and c.1073C>T; p.(P358L)), as well as 5 previously reported recurrent variants (c.10A>C; p.(I4L), c.426dupG; p.(T143Dfs*12), c.527C>T; p.(S176L), c.763G>A; p.(V255M), and c.1057G>A; p.(V353I)) (Table 1). Among these families, 3 variants (c.721C>T; p.(R241C), c.1205dupG; p.(M403Hfs*3), and c.1270C>T; p.(Q424*)) were homozygous, 2 variants (c.[322G>A]; [426dupG]; p.(E108K); (T143Dfs*12) and c.[1286C>T]; [1301_1327del]; p.(T429M); (434_442del)) were compound heterozygous, and 25 variants were heterozygous. Among the 25 heterozygous variants, 5 were inherited, 9 were de novo and the other 11 were unknown inheritance pattern due to unavailability of DNA samples of their parents (Fig. 1). The position of variants was indicated in Fig. 2a. It is worth noting that variants in the patient from Family 8 (c.[1286C>T]; [1301_1327del]; p.(T429M); (434_442del)) and Family 4 (c.883G>C; p.(D295H)) were passed on from her mother, indicating that incomplete penetrance of variants may occur. It is also possible that there might exist a modifier gene in the two families. In silico analysis showed that nearly all of the variants are deleterious to the function of TUBB8 as predicted by PolyPhen-2 and PROVEAN and that they all have extremely rare frequencies (<10−4) or are absent in the EXAC database. In addition, all altered residues are strictly evolutionarily conserved among primate species (Fig. 2b).

Table 1.

TUBB8 variant spectrum in the 30 unrelated patients with failure of oocyte maturation and embryonic development

| Family | Position on chr.10 (bp) | cDNA | Protein change | Inheritance pattern | Variant type | PPH2a | PROVEANa | EXAC easb | EXACb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Families 1/22 | 93,569 | c.763G>A | p.(V255M) | Dominant/unknown | Missense | Probably damaging | Neutral | 0 | 6.77E−05 |

| Families 2/16/30 | 93,259 | c.1073C>T | p.(P358L) | Dominant/De novo/Unknown | Missense | Probably damaging | Deleterious | / | / |

| Family 3 | 93,332 | c.1000C>G | p.(Q334E) | Dominant | Missense | Probably damaging | Neutral | / | / |

| Family 4 | 93,449 | c.883G>C | p.(D295H) | Incomplete dominance | Missense | Probably damaging | Deleterious | / | / |

| Family 5 | 93,233 | c.1099T>C | p.(F367L) | Dominant | Missense | Probably damaging | Deleterious | / | / |

| Family 6 | 94,010 | c.322G>A | p.(E108K) | Dominant | Missense | Probably damaging | Deleterious | 0.000348 | 0.000033 |

| 93,906dup | c.426dupG | p.(T143Dfs*12) | Recessive | Frameshift insertion | / | / | 0.000231 | 4.13E−05 | |

| Family 7 | 93,062 | c.1270C>T | p.(Q424*) | Recessive | Non-sense | / | / | / | / |

| Family 8 | 93,046 | c.1286C>T | p.(T429M) | Incomplete dominance | Missense | Probably damaging | Neutral | 0 | 2.69E−05 |

| 93,005_93,031del | c.1301_1327del | p.(434_442del) | Incomplete dominance | In-frame deletion | / | Deleterious | / | / | |

| Family 9 | 93,127dup | c.1205dupG | p.(M403Hfs*3) | Recessive | Frameshift insertion | / | / | / | / |

| Family 10 | 93,611 | c.721C>T | p.(R241C) | Recessive | Missense | Probably damaging | Deleterious | / | / |

| Family 11 | 93,260 | c.1072C>G | p.(P358A) | De novo | Missense | Probably damaging | Deleterious | / | / |

| Family 12/29 | 94,040 | c.292G>A | p.(G98R) | De novo/unknown | Missense | Probably damaging | Deleterious | / | / |

| Family 13 | 93,597 | c.735G>C | p.(Q245H) | De novo | Missense | Probably damaging | Deleterious | / | / |

| Family 14 | 93,271 | c.1061G>A | p.(C354Y) | De novo | Missense | Probably damaging | Deleterious | / | / |

| Family 15 | 94,651 | c.181C>A | p.(P61T) | De novo | Missense | Probably damaging | Deleterious | / | / |

| Family 17/26 | 95,169 | c.10A>C | p.(I4L) | De novo/unknown | Missense | Benign | Neutral | 0.000488 | 2.75E−05 |

| Family 18/27 | 93,805 | c.527C>T | p.(S176L) | De novo/unknown | Missense | Probably damaging | Deleterious | / | / |

| Family 19 | 93,610 | c.722G>A | p.(R241H) | Unknown | Missense | Probably damaging | Deleterious | 0 | 8.9E−06 |

| Family 20 | 93,083 | c.1249G>T | p.(D417Y) | Unknown | Missense | Probably damaging | Deleterious | / | / |

| Family 21 | 93,809 | c.523G>A | p.(V175M) | Unknown | Missense | Probably damaging | Neutral | / | / |

| Family 23 | 93,275 | c.1057G>A | p.(V353I) | Unknown | Missense | Benign | Neutral | / | / |

| Family 24 | 93,732 | c.600T>G | p.(F200L) | Unknown | Missense | Benign | Deleterious | / | / |

| Family 25 | 93,161 | c.1171C>T | p.(R391C) | Unknown | Missense | Probably damaging | Deleterious | / | / |

| Family 28 | 93,104 | c.1228G>A | p.(E410K) | De novo | Missense | Probably damaging | Neutral | / | / |

/ not available

aVariant effect predicted by PolyPhen-2 (PPH2) and PROVEAN

bFrequency of corresponding variants in the East Asian (eas) and total population of ExAC

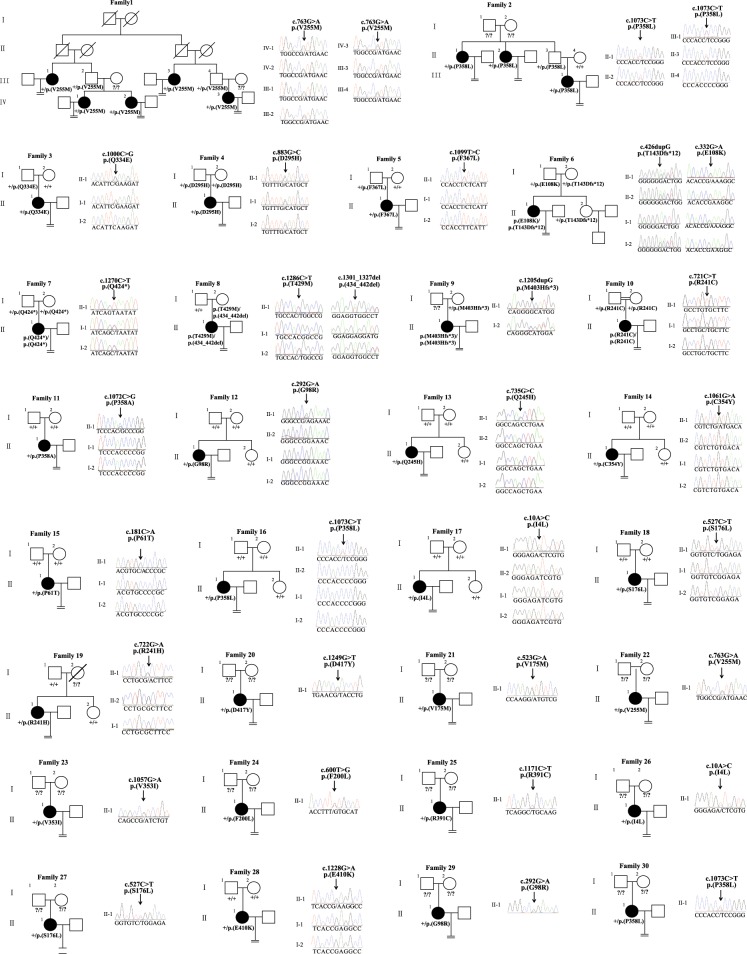

Fig. 1.

Pedigrees of 30 families with TUBB8 variants. Sanger sequencing chromatograms are shown to the right of the pedigrees. The “=” sign indicates infertility, and the double line indicates consanguinity. Black circles represent affected individuals, and question marks indicate the absence of DNA samples. “+” means wild type

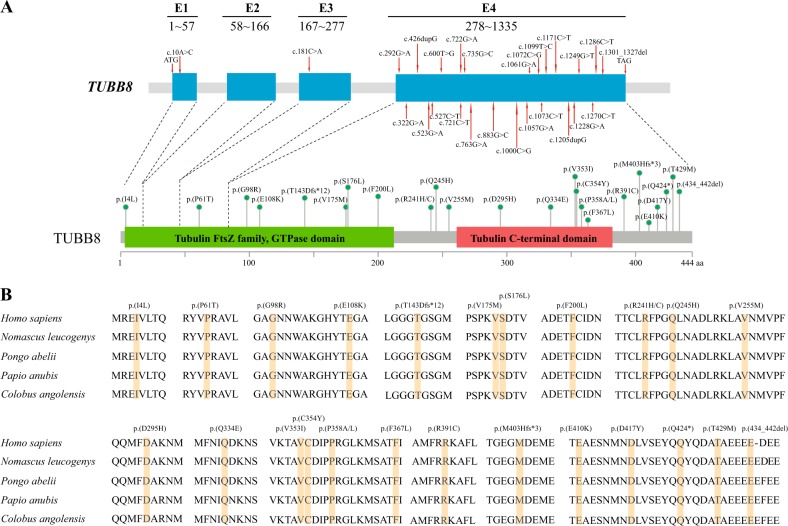

Fig. 2.

Primary structure and conservation analysis of altered amino acids in TUBB8. a The positions of altered alleles are shown on the gene structure of TUBB8, and the corresponding amino acids are indicated by green circles on the TUBB8 protein. All of the variants are found in Exon 4 except for c.10A>C and c.181C>A. The boundaries of exons are indicated from start codon (ATG) to terminal codon (TAG). b Conservation analysis of altered amino acids among five primate species

Phenotypic spectrum of patients with TUBB8 variants

The clinical characteristics of the oocytes retrieved from the affected individuals are summarized in Table 2. Polarization microscopy determination and immunofluorescence analysis showed that some affected individuals had missing or abnormal spindles in contrast to the spindles seen in normal MI oocytes (Fig. 3). Our results showed that the patients carrying different variants had variable phenotypes, including (1) oocytes that were completely arrested at an immature stage, especially at the MI stage (Families 2/5/9/10/11/13/16/19/21/22/27/29), (2) first polar body (PB1) oocytes that could be retrieved, but failed to be fertilized (Families 6/7/17/28), (3) PB1 oocytes that could be fertilized, but the embryos failed to cleave (Families 1/15/17/23), (4) PB1 oocytes that could be fertilized and the embryos could be cleaved, but the embryos subsequently led to developmental abnormalities at an early stage (Families 3/4/20/24/25/26), and (5) some normal appearing embryos that had implantation potential (Families 3/4/15/17/20/23/26) but failed to conceive after implantation. These observations further expand the range of dysfunctional oocyte and embryo phenotypes that result from TUBB8 variants.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of the patients with TUBB8 variants

| Family | Age (years) | Duration of infertility (years) | Previous IVF and ICSI cycles | Total oocytes retrieved | GV oocytes | MI oocytes | Immature oocytes of unknown stage | PB1 oocytes | Oocytes with abnormal morphology | Fertilized oocytes | No. of embryos that could be cleaved | Usable embryos | Outcome of embryo transfer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 | 5 | 3 | 13 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 0 | / |

| 2 | 33 | 5 | 2 | 14 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | / |

| 3 | 31 | 5 | 3 | 34 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 10 | 4 | 2 | Failure |

| 4 | 33 | 9 | 2 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | Not transferred |

| 5 | 24 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | / |

| 6 | 39 | 12 | 2 | 27 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 20 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | / |

| 7 | 29 | 5 | 3 | 40 | 7 | 11 | 0 | 19 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | / |

| 9 | 30 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | / |

| 10 | 34 | 12 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 11 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | / |

| 11 | 23 | 5 | 1 | 15 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | / |

| 13 | 30 | 3 | 3 | 26 | 0 | 7 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | / |

| 14 | 36 | 14 | 4 | 39 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | / |

| 15 | 29 | 4 | 4 | 20 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 16 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 1 | Failure |

| 16 | 31 | 8 | 5 | 32 | 2 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | / |

| 17 | 35 | 12 | 3 | 26 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 21 | 1 | 4 | 1 | Failure | |

| 19 | 33 | 6 | 2 | 16 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | / |

| 20 | 32 | 4 | 2 | 31 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 25 | 1 | 18 | 13 | 3 | Failure |

| 21 | 34 | 8 | 2 | 12 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | / |

| 22 | 30 | 5 | 2 | 26 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | / |

| 23 | 28 | 3 | 3 | 62 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 59 | 1 | 19 | 1 | 1 | Failure |

| 24 | 34 | / | 1 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 0 | 23 | 13 | 0 | / |

| 25 | 30 | 5 | 5 | 34 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 28 | 4 | 11 | 11 | 0 | / |

| 26 | 27 | / | 1 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 1 | Failure |

| 27 | 28 | 7 | 2 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | / |

| 28 | 26 | 3 | 2 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | / |

| 29 | 31 | 8 | 1 | 14 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | / |

Families 8/12/18/30 had no clinical information

I not available

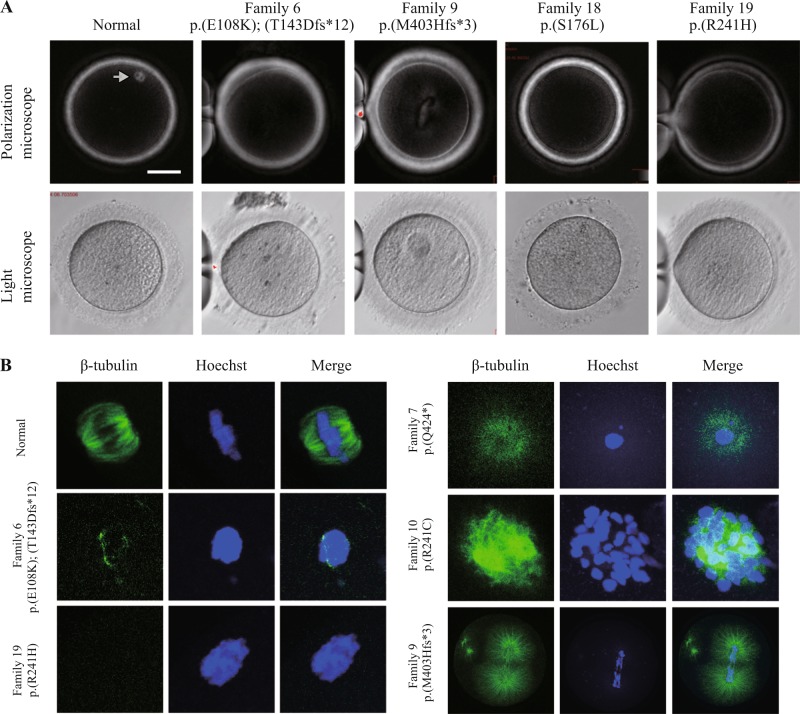

Fig. 3.

Phenotypes of oocytes from patients with oocyte maturation arrest. a The morphologies of control and patient oocytes examined by light and polarizing microscopy. A normal MI oocyte has a visible spindle under polarized light, as indicated by the gray arrow, while patients with TUBB8 variants have missing or abnormal spindles. b Immunostaining analysis of oocytes from patients. Oocytes were immunolabeled with an anti-β-tubulin antibody to visualize the spindle (shown in green) and counterstained with Hoechst 33342 to visualize the DNA (shown in blue). Scale bars in a 50 µm

Discussion

In this study, we identified an additional 25 families with heterozygous variants, 3 families with homozygous variants, and 2 families with compound heterozygous variants in TUBB8, and these included dominant and recessive inheritance patterns and de novo variants. The variants cause variable phenotypes, including abnormalities in oocyte maturation, fertilization, embryonic development, and implantation. In addition, it is worth noting that the patients in Family 4 and Family 8 had variants inherited from their mothers, which suggests that an incomplete penetrance pattern might exist for these variants. Alternatively, a modifier gene might exist in the two families.

We previously established that TUBB8 is mainly involved in the assembly of human oocyte spindles [11], and it is notable that the three homozygous variants (c.721C>T; p.(R241C), c.1205dupG; p.(M403Hfs*3), and c.1270C>T; p.(Q424*)) are predicted to result in no functional β-tubulin VIII polypeptides in the oocytes. Consistent with our previous study [12], oocytes carrying these three variants exhibited visible spindles by immunostaining, but these spindles all had aberrant morphologies (Fig. 3). These results further confirm that other β-tubulin isotypes also contribute to spindle formation and further demonstrate that the TUBB8 protein is required for proper spindle assembly and morphology.

Oocytes with normal competence refers to oocytes that undergo both nuclear maturation, as indicated by extruding PB1, and cytoplasmic maturation, as indicated by development into successfully implanted embryos. In addition to the previously observed phenotypes of oocyte maturation arrest, fertilization failure, and early embryonic arrest that result from TUBB8 variants [11–13], we also identified a novel phenotype in which patients (Families 3/4/15/17/20/23/26) with TUBB8 variants have viable embryos but suffer from recurrent implantation failure. This phenotype might result from internal embryonic developmental abnormalities due to TUBB8 variants, despite of seemingly normal morphology. Thus, our present results expand the mutational and phenotypic spectrum of TUBB8 in infertility patients. We hypothesize that the differentiated phenotypes incurred by the different variants result from different three-dimensional protein conformations that alter the interactions between TUBB8 and other microtubule-associated proteins.

When combining our previous and current data, variants in TUBB8 account for 35.4% of all 130 patients that we have identified with recurrent failure of IVF and ICSI caused by problem with oocytes and embryos. Thus, TUBB8 mutation screening might not only be a genetic diagnostic marker of oocyte maturation arrest for this specific cohort of patients, but might also have clinical implications for evaluating the competence of patients’ functional PB1 oocytes.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFC1001500 and 2016YFC1000600), the National Basic Research Program of China (2015CB943300), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81725006, 81822019, 81771581, 81571501), and the Shanghai Rising-Star Program (17QA1400200). No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Qing Sang, Email: sangqing@fudan.edu.cn.

Lei Wang, Email: wangleiwanglei@fudan.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Clift D, Schuh M. Restarting life: fertilization and the transition from meiosis to mitosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:549–62. doi: 10.1038/nrm3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capalbo A, Hoffmann ER, Cimadomo D, Maria Ubaldi F, Rienzi L. Human female meiosis revised: new insights into the mechanisms of chromosome segregation and aneuploidies from advanced genomics and time-lapse imaging. Hum Reprod Update. 2017;23:706–22. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmx026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li R, Albertini DF. The road to maturation: somatic cell interaction and self-organization of the mammalian oocyte. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:141–52. doi: 10.1038/nrm3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coticchio G, Dal Canto M, Mignini Renzini M, et al. Oocyte maturation: gamete-somatic cells interactions, meiotic resumption, cytoskeletal dynamics and cytoplasmic reorganization. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21:427–54. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmv011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beall S, Brenner C, Segars J. Oocyte maturation failure: a syndrome of bad eggs. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:2507–13. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudak E, Dor J, Kimchi M, Goldman B, Levran D, Mashiach S. Anomalies of human oocytes from infertile women undergoing treatment by in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 1990;54:292–6. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)53706-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eichenlaub-Ritter U, Schmiady H, Kentenich H, Soewarto D. Recurrent failure in polar body formation and premature chromosome condensation in oocytes from a human patient: indicators of asynchrony in nuclear and cytoplasmic maturation. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:2343–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartshorne G, Montgomery S, Klentzeris L. A case of failed oocyte maturation in vivo and in vitro. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:567–70. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(98)00505-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergere M, Lombroso R, Gombault M, Wainer R, Selva J. An idiopathic infertility with oocytes metaphase I maturation block: case report. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:2136–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.10.2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmiady H, Neitzel H. Arrest of human oocytes during meiosis I in two sisters of consanguineous parents: first evidence for an autosomal recessive trait in human infertility: case report. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2556–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.10.2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng R, Sang Q, Kuang Y, et al. Mutations in TUBB8 and human oocyte meiotic arrest. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:223–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng R, Yan Z, Li B, et al. Mutations in TUBB8 cause a multiplicity of phenotypes in human oocytes and early embryos. J Med Genet. 2016;53:662–71. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-103891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen B, Li B, Li D, et al. Novel mutations and structural deletions in TUBB8: expanding mutational and phenotypic spectrum of patients with arrest in oocyte maturation, fertilization or early embryonic development. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:457–64. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang L, Tong X, Luo L, et al. Mutation analysis of the TUBB8 gene in nine infertile women with oocyte maturation arrest. Reprod Biomed Online. 2017;35:305–10. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2017.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–91. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi Y, Sims GE, Murphy S, Miller JR, Chan AP. Predicting the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi Y, Chan AP. PROVEAN web server: a tool to predict the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:2745–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]