Abstract

Presymptomatic testing for hereditary cancer syndromes should involve a considered choice. This may be particularly challenging when testing is undertaken in early adulthood. With the aim of exploring the psychosocial implications of presymptomatic testing for hereditary cancer in young adults and their parents, a cross-sectional survey was designed. Two questionnaires were developed (one for young adults who had considered presymptomatic testing, one for parents). Questionnaires were completed by 152 (65.2%) young adults and 42 (73.7%) parents. Data were analysed using descriptive statistics, inferential testing, and exploratory factor analysis and linear regression analysis. Young adults were told about their potential genetic risk at a mean age of 20 years; in most cases, information was given by a parent, often in an unplanned conversation. Although testing requests were usually made by young adults, the majority of parents felt they had control over the young adult’s decision and all felt their children should be tested. Results suggest that some young adults did not understand the implications of the genetic test but complied with parental pressure. Counselling approaches for presymptomatic testing may require modification both for young adults and their parents. Those offering testing need to be aware of the complex pressures that young adults can experience, which can influence their autonomous choices. It is therefore important to emphasise to both parents and young adults that, although testing can bring benefits in terms of surveillance and prevention, young adults have a choice.

Subject terms: Genetic counselling, Patient education

Introduction

Presymptomatic genetic testing (PST) involves testing to determine if a person has inherited a gene variant that causes a familial condition, before the person has any signs or symptoms of the condition [1]. This type of testing is available for a number of heritable genetic disorders, including some hereditary cancer syndromes [1]. The results of PST for hereditary cancer syndromes may allow individuals to engage in healthy lifestyle choices or seek early treatment for symptoms [2, 3]. Some key challenges associated with the transition from adolescence to adulthood can include completing education, beginning full-time employment, forming romantic/sexual relationships, marriage and becoming a parent: the impact of testing may affect, and be affected by, each of these events.

A variety of psychosocial responses have been observed in people who have chosen to be tested [4–6]. Various guidelines and position papers have been produced on PST in minors [7]. It is clearly suggested that undergoing PST too early in life may increase the risk of unfavourable impact, and, therefore, the appropriate age to undergo PST is still a matter of debate [7–9]. For these reasons, PST for adult-onset disorders is not generally recommended for those aged less than 18 years, unless it is in a child’s best interests either in terms of immediate relevance for their health or because it involves psychological or social benefits [10]. Although the definition of a young adult (YA) can be extremely broad and is not often clear in terms of one specific age group, the definition proposed by Rindfuss [11] (18–30 years) was used: 18 years is an age that is often recognised in law and 30 years often represents time for taking stock in life. Prior to testing, YA need to be aware of the potential risk to them of hereditary cancer, and this is usually disclosed by their parents [12–14]. A systematic review [15] on this topic indicated that many YA or adolescents (14–30 years) grew up with little or no information concerning their genetic risk and that parents had exerted pressure during the testing decision-making process. An empirical qualitative study [16] conducted in Italy indicated that YA made a decision to be tested before approaching genetic services, and had not realised that they could use genetic counselling to make a choice. However, the process of genetic counselling enabled them to act more autonomously and to adapt to the results. This study was designed to build on those results and further explore the psychosocial implications of PST for hereditary cancer in YA and their parents. Specific objectives were to investigate how YA interpret PST, the reasons for the YA’s decision to undergo testing, the experience of the counselling process of both YA and parents and the influence that parents have both on the choice to be tested and on the YA’s decisions after receiving a positive test result.

Materials and methods

The study design was a cross-sectional self-completion survey [17]. This study received ethics approval from both St. Orsola-Malpighi Hospital Ethical Board (198/2015/O/Oss), and Plymouth University Faculty Research Ethics Committee (15/16-519).

Recruitment and participants

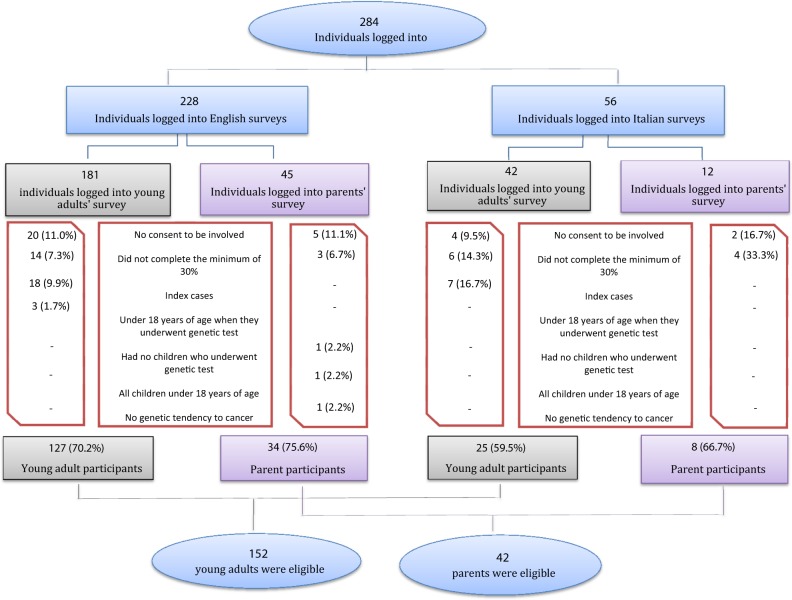

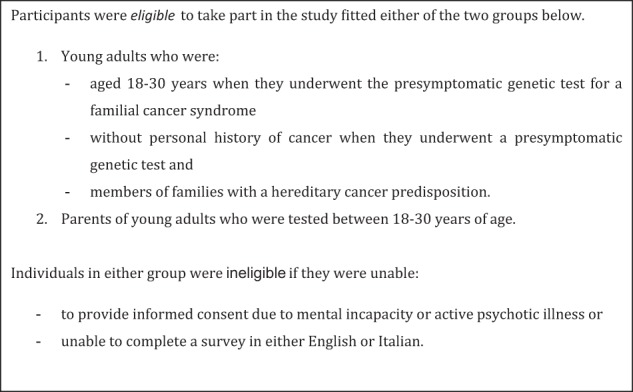

To maximise accessibility to the survey, online and traditional methods of recruitment and data collection were used. Although online surveys are a convenient way of collecting data from a wide range of people [18], there is evidence that many members of the Italian population do not use the Internet regularly [19]. Data were collected using: (i) online questionnaires (Italian and English version) uploaded to the Survey Monkey® website (for example using social networks) and ii) paper versions (Italian) of the same questionnaire. Traditional recruitment was used only at St. Orsola-Malpighi Hospital, Italy, and specific ethical approval was obtained for that. Every YA or parent of a YA who had been tested who met the inclusion criteria was invited to take part in the study. Parents and YA who responded were not necessarily related to each other. The surveys were open to respondents between December 2015 and June 2016. Inclusion and exclusion criteria and the recruitment flow-chart are presented respectively in Figs. 1 and 2.

Fig. 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Fig. 2.

Recruitment flow-chart

Questionnaire

Since it was important to investigate both consultands’ (YA aged 18–30 years [11]) and parents’ points of view, two questionnaires were designed. The questions were based on the results of a systematic review [15] and a qualitative study of YA’s experiences of PST [16] and on other similar surveys [20, 21]. The questionnaires were written both in Italian and English (English version in supplementary files).

Data analysis

In this cross-sectional study, data were entered into a dedicated database (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Ver. 21.0 for Windows) (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA), arranged by variables and analysed using descriptive and inferential statistical tests. Descriptive statistics were used to determine the mean, standard deviation, percentage and frequency of variables. The chi-squared test for independence was used to discover if there was a relationship between two categorical variables [22]. The Fisher’s exact test, the independent t-test and ANOVA were used to analyse the data inferentially [23]. Post-hoc tests were also performed where appropriate [22]. Furthermore, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was carried out to reduce the number of variables, by identifying a limited number of underlying factors explaining multiple observed variables [23–25]. EFA led to identify 20 factors under six main questions (See Supplementary Table 1). The factors were also analysed using descriptive statistics and hypothesis testing to analyse the data inferentially. Simple and multiple linear regression analysis were then used to identify effects of independent variables (dummy-coded) on the factors identified by EFA (dependent variables); detailed data from multiple linear regression are reported in Supplementary Table 2a–e. Throughout the study, results were considered statistically significant when the p-value was less than .05. For further information on the methods used for statistical analyses, see Supplementary Files.

Rigour

To ensure rigour, a pilot of the survey was conducted with five colleagues, in order to test the online surveys and data extraction. The same SPSS syntax was used for the analysis to ensure reproducibility, and to allow any reader to verify what has been done.

Results

Sample characteristics

Of 233 individuals who logged onto the YA survey site and 57 individuals who logged onto the parent survey site, 152 (65.2%) and 42 (73.7%) respectively provided both consent and complete data and were included in the analysis.

Young adult questionnaire results

The demographic information provided by the study participants is shown in Table 1. The majority of participants (n = 142; 93.4%) were variant-positive, and among those 6.3% (n = 9) had been diagnosed with cancer since having their PST. The number of females who completed the English questionnaire (PEQ) was significantly higher when compared to men (134/140, 95.7 vs. 7/11, 63.6%; p = .003, Fisher’s exact test). Among the PEQ the majority were variant-positive (96.9%) while in the Italian sample (PIQ) there were 19 (76.0%) variant-positive and six (24.0%) variant-negative respondents (p = .001, Fisher’s exact test).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics: young adult participants

| All (n = 152) | PEQ (n = 127) | PIQ (n = 25) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at questionnaire (years) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 29.5 ± 5.6 | 29.6 ± 5.9 | 28.7 ± 3.7 | 0.463a |

| Age at PST (years) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 24.7 ± 3.7 | 24.7 ± 3.8 | 25.0 ± 3.4 | 0.700a |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 11 (7.2%) | 2 (1.6%) | 9 (36.0%) | 0.000b,c |

| Female | 140 (92.1%) | 124 (97.6%) | 16 (64.0%) | |

| I prefer not to say | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 | |

| Country | ||||

| Italy | 25 (16.4%) | 0 | 25 (100%) | – |

| United Kingdom | 63 (41.4%) | 63 (49.6%) | 0 | |

| United States of America | 47 (30.9%) | 47 (37.0%) | 0 | |

| Other countries | 17 (11.2%) | 17 (13.4%) | 0 | |

| Education | ||||

| Primary school | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 | 0.191b |

| Secondary school | 15 (9.9%) | 15 (11.8%) | 0 | |

| Post-secondary educ. | 49 (32.2%) | 38 (29.9%) | 11 (44.0%) | |

| University degree | 62 (40.8%) | 50 (39.4%) | 12 (48.0%) | |

| Postgraduate degree | 25 (16.4%) | 23 (18.1%) | 2 (8.0%) | |

| Daily work | ||||

| Paid employment | 112 (73.7%) | 94 (74.0%) | 18 (72.0%) | 0.176b |

| Voluntary employment | 2 (1.3%) | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (4.0%) | |

| Student | 18 (11.8%) | 13 (10.2%) | 5 (20.0%) | |

| Homemaker | 15 (9.9%) | 15 (11.8%) | 0 | |

| Not working not student | 5 (3.3%) | 4 (3.1%) | 1 (4.0%) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single (never married) | 48 (31.6&) | 33 (26.0%) | 15 (60.0%) | 0.009b |

| Married | 67 (44.1%) | 60 (47.2%) | 7 (28.0%) | |

| Divorced | 7 (4.6%) | 6 (4.7%) | 1 (4.0%) | |

| Living with a partner | 30 (19.7%) | 28 (22.0%) | 2 (8.0%) | |

| Children | ||||

| Yes | 73 (48.0%) | 69 (54.3%) | 4 (16.0%) | 0.000d |

| No | 79 (52.0%) | 58 (45.7%) | 21 (84.0%) | |

| Condition tested | ||||

| Cowden syndrome | 1 (0.7%) | |||

| Familial adenomatous polyposis | 14 (9.2%) | |||

| Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer | 111 (73.0%) | |||

| Lynch syndrome | 26 (17.1%) | |||

PEQ was used to indicate the participants responding to the English questionnaire and PIQ the participants responding to the Italian questionnaire

aIndependent samples T-test

bPearson χ2 test

c“I prefer not to say” answer was excluded from the analysis

dFisher's exact test

Finding out about their risk

Participants declared they received the information about their risk for the first time when between 5 and 30 years of age (20.0 ± 5.6): 111 (75.5%) were informed after their 18th birthday, while 36 (24.5%) were informed earlier. Fifty-four YA participants (35.5%) were told by their mother, 19 (12.5%) by their father, 16 (10.5%) by both parents together, seven (4.6%) by their sister, 24 (15.8%) by other relatives such as aunts or cousins, and 26 (17.1%) by a person outside the family such as a genetic counsellor or a physician. Three participants (2.0%) had suspected they were at risk because of a family history of cancer and sought medical advice, and three (2.0%) reported the risk was openly discussed within their family. One-hundred and two participants (68.5%) reported they received the information at an unplanned time (75 in a face-to-face conversation and 27 in a telephone or social media call/message), while 43 (28.9%) received the information in a pre-planned conversation (38 in a face-to-face meeting and five in a telephone call). Two participants did not remember how they received the information. The majority of participants (n = 132; 86.8%) were told at that time that the tendency to cancer in their family could be due to a genetic change. A significant difference was observed in relation to the time taken for testing after disclosure: 73.1% of participants who had received the information from a person outside the family underwent PST within one year of obtaining the information (χ2 = 19.951, df = 9, p = .018), compared to 41.7% of those told by a family member. Participants who were told about their potential genetic risk before their 18th birthday showed lower awareness of their risk (Q1, F1) (Betabefore18 = −.187, R2 = .028, p = .026) and lower need for additional information (Q1, F2) (Betabefore18 = −.173, R2 = .037, p = .023).

Decision-making process

The majority of participants (n = 105; 75.5%) responded “myself” when asked about the person who decided that they would be tested, while “both myself and parents” was mentioned by 23 (16.5%), “parents” by four (2.9%), “aunt” by four (2.9%), and genetic counsellor/doctor by three (2.2%). The proportion of PEQ reporting the decision as made by themselves was significantly higher if compared to PIQ (96/116, 82.8% vs. 9/23, 39.1%; χ2 = 38.715, df = 4, p < .001). Participants who underwent PST within one year of obtaining the information were more likely to show proactivity (Q3, F1) than those who underwent PST between two and four years after (3.9 ± 0.9 vs. 3.2 ± 1.3; F = 2.987, p = .034). Becoming aware of potential genetic risk before age 18 or being informed by distant relatives predicted a lower perception of parents’ pressure against testing (Q3 F2) (Betabefore18 = −.220, Betaother-relatives = −.617), unlike being tested between 18-25 years of age, that predicted higher perception of parents disagreement about testing (Betabefore25 = .260) (F(11,90) = 2.028, p = .034). Men were found more likely than women to have undergone genetic testing because of their parent’s decision both using variance analysis (3.4 ± 1.3 vs. 1.6 ± 1.4; t(135) = 4.640, p < .001) and multiple linear regression (Betafemale = .410). Pressure from parents toward testing was reported more frequently by participants without children than by those who had children (3.1 ± 1.4 vs. 2.5 ± 1.4; t(134) = −2.771, p = .006), with a correlation confirmed by multiple linear regression (Betawith-children = −.264). Also, participants who became aware of their risk before age 18 were less likely to undergo PST upon their parents’ decision (Q3,F3) (Betabefore18 = −.183) (F(11,110) = 4.368, p < .001). Pressure by parents was more frequently reported by participants tested between 18-25 years than by those undergoing genetic testing between 26-30 years of age (3.0 ± 1.4 vs. 2.5 ± 1.4; t(134) = 2.202, p = .029).

Genetic test result

Respondents to the English questionnaire were more likely than PIQ to experience negative feelings (2.9 ± 0.9 vs. 2.4 ± 1.1; t(131) = 2.596, p = .011), and to worry for relatives (2.8 ± 0.9 vs. 2.2 ± 0.9; t(133) = 2.557, p = .012). Participants who had received the information on their risk in an unplanned conversation/call were more likely to experience negative feelings about their genetic test result (3.0 ± 0.8 vs. 2.7 ± 0.9; t(125) = 2.060; p = .041). A positive test result significantly predicted higher frequency of negative feelings about test outcome (Q4,F1) (Betagene-found = .321) (F(11,111) = 2.939, p = .002). Moreover, participants who received a positive test result were more likely to worry about their relatives (2.7 ± 0.9 vs. 1.8 ± 0.8; t(133) = 3.316, p = .001); (Betagene-found = .213). Also having children was a significant predictor of worrying about relatives (Q4,F4) (Betawith-children = .287), (F(11,113) = 2.098, p = .026). Having being diagnosed with cancer significantly reduced the perception of the test as helpful (Q4,F5) (Betacancer = −.198) (F(11,111) = 3.072, p = .001).

Living with genetic risk

Italian participants were more likely to perceive the influence of lifestage (2.2 ± 1.1 vs. 1.4 ± 1.1; t(127) = −2.701, p = .008), as well as those who were diagnosed with cancer (Betacancer = .289). Conversely, having children predicted a lower perception of lifestage influence (Q5,F1) (Betawith-children = −.285) (F(11,108) = 3.211, p = .001). Participants who received a positive test result were significantly more likely to perceive it as helpful to their own prevention and for relatives than those who received a negative test result (3.0 ± 0.8 vs. 1.7 ± 1.2; t(121) = 3.343, p = .001) (Betagene-found = .332, F(11,102) = 1.956, p = .041); this was also true for participants who underwent PST between 18 and 25 years of age (2.0 ± 0.7 vs. 2.2 ± 0.8; t(121) = 2.127, p = .035) when compared to those tested at 26–30 years. Consistently, participants who received a positive test result were more likely to feel anxious than those who received a negative test result (2.2 ± 0.7 vs. 1.2 ± 0.7; t(125) = 3.043, p = .003) (Betagene-found = −.237, p = .012) (F(11,107) = 2.246, p = .017).

Parent questionnaire results

The demographic information provided by the study participants is shown in Table 2. The majority of participants (n = 25, 59.5%) had been previously diagnosed with cancer and 37 (88.1%) declared that there was a genetic tendency to cancer on their side of the family. Among those, 35 (94.6%) had a genetic test at 47.4 ± 6.2 age of years. Ten (23.8%) of those who had a PST had never had cancer.

Table 2.

Sample charactheristics: parent participants

| All (n = 42) | PEQ (n = 34) | PIQ (n = 8) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at questionnaire (years) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 51.9 ± 7.6 | 51.7 ± 7.3 | 55.1 ± 3.8 | 0.211a |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 4 (9.5%) | 4 (100.0%) | 0 | 0.572c |

| Female | 38 (90.5%) | 30 (78.9%) | 8 (21.1%) | |

| Country | ||||

| Italy | 8 (19.0%) | 0 | 8 (100.0%) | – |

| United Kingdom | 17 (40.5%) | 17 (50.0%) | 0 | |

| United State of America | 11 (26.2%) | 11 (32.4%) | 0 | |

| Other countries | 6 (14.3%) | 6 (17.6%) | 0 | |

| Education | ||||

| Secondary school | 10 (23.8%) | 9 (26.5%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0.461b |

| Post-secondary educat. | 20 (47.6%) | 15 (44.1%) | 5 (62.5%) | |

| University degree | 7 (16.7%) | 5 (14.7%) | 2 (25.0%) | |

| Postgraduate degree | 5 (11.9%) | 5 (14.7%) | 0 | |

| Daily work | ||||

| Paid employment | 29 (69.0%) | 23 (67.6%) | 6 (75.0%) | 0.392b |

| Homemaker | 7 (16.7%) | 5 (14.7%) | 2 (25.0%) | |

| Not working not student | 6 (14.3%) | 6 (17.6%) | 0 | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single (never married) | 1 (2.9%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0 | 0.378b |

| Married | 32 (76.2%) | 24 (70.6%) | 8 (100.0%) | |

| Married | 8 (19.0%) | 8 (23.5%) | 0 | |

| Living with a partner | 1 (2.4%) | 1 (2.3%) | 0 | |

| Condition tested | ||||

| Cowden syndrome | 4 (11.4%) | |||

| Familial adenomatous polyposis | 1 (2.9%) | |||

| Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer | 24 (68.6%) | |||

| Lynch syndrome | 6 (17.1%) | |||

aIndependent samples T-test

bPearson χ2 test

cFisher's exact test

Telling your children

All participants reported that they had told their children about the family risk themselves; the age of the children when told ranged from 5 to 44 years (21.8 ± 6.6). The majority (n = 28, 66.7%) decided to disclose the information in a planned conversation with their child(ren), eight (19.0%) told them in a casual way, and six (14.3%) took advantage of a moment when the child raised the issue. Concerning parents’ reasons for telling their children about the family cancer risk, it was observed that participants who underwent genetic testing after having cancer were more likely to worry about the emotional impact on the child than those who underwent it before having cancer (2.3 ± 1.1 vs. 0.8 ± 0.8; F = 2.944, p = .050). However, participants who communicated the family cancer risk in a casual way to their children were less likely to have difficulties in communicating genetic status than those who planned a conversation with them (2.3 ± 1.7 vs. 1.0 ± 1.1; F = 4.164, p = .025). Consistently, a significant difference was found between participants with a genetic tendency to cancer in their partner’s side of the family and participants with a genetic tendency in their own side of family: the first group were less likely to have difficulties in communicating genetic status (2.4 ± 1.1 vs. 0.7 ± 0.9; t(23) = 3.952, p = .001).

Children’s experience of the PST

The majority (n = 38, 94.7%) of parent participants told their children about the possibility of having a PST. Parents reported that the request for PST was made by the adult child themselves in 28 cases (73.7%), by the child with one or both of the parents in five cases (13.2%), by the respondent or his partner in four cases (10.5%), and by the doctor in one case (2.6%).

Parents’ feelings about PST for their children

Guilt about the possibility that the mutation might be inherited by their children (parent questionnaire, question 80 in suppl. file) was more common in the mothers (Betamother = .349 R2 = .122). (F(1,34) = 4.722, p = .037). However, all participants felt their children should be tested. The majority (n = 26, 74.3%) also felt they had control over the decision their child made about the test.

Discussion

The findings of this study suggest that young adults were told about the potential genetic risk at a mean age of 20 ± 5.6 years. This is older than the age of 13.5 ± 2.6 years in the American sample described by Tercyak et al. [23] and in general in the systematic review [15], where about half were informed before the age of 18 years old and all before 21 years of age. However, no YA was younger than 12 years of age when informed [15]. In contrast, in our sample the large majority (75.5.%) were informed after their 18th birthday. The large majority (68.5%) received the information in an unplanned conversation and only 2% of our sample reported that genetic risk was openly discussed in their family. We did not collect data on the age at which parents were tested, so were not able to compare the age at which the child was informed with the parents at which parents received their own test result, but this would be interesting to study in future. Informal discussion about their potential genetic risk was preferred by young people described by Metcalfe et al. [25] and in our sample parents were less likely to have difficulties in communicating genetic risk when it happened in a casual way, as well as when they communicated the genetic risk of their partner’s side of the family. However, YA who were told about their genetic risk in an unplanned situation were more likely to report negative feelings about their genetic test result. It could be hypothesised that a communication perceived by a YA to be ‘casual’ may hamper the full understanding of the risk, thus increasing the chance of a negative emotional impact. The majority of parents reported that they disclosed the information in a planned conversation, while the majority of YA reported that discussions were not usually planned, and due to anonymity of participants, we were not able to determine if participants (both YA and parents) belonged to the same families. In any case, it may be that a conversation that was planned by parents may have appeared unplanned to their children. The fact that parents made the decision to disclose without involving health professionals is concerning as Borry et al. [10] reported that parents were not able to transmit accurate information to their children regarding their genetic risk. It is possible that parents have not perceived the existence of support from genetic counsellors, even though Metcalfe et al. [26] showed that health professionals are increasingly being asked for advice from parents about risk disclosure to their children. However, reluctance by parents to involve health professionals may be partly due to the parents’ wish to undertake this task alone [26, 27]. While a previous systematic review [15] suggested that positive and negative emotional outcomes were not correlated with test results, our participants who received a variant-positive test result were more likely to experience negative feelings. Although the majority of the requests for genetic testing were made by YA offspring, the majority of parent participants felt they had control over the decision their child made about the test and all felt their children should be tested, which is in line with previous findings, where parents appeared to have exerted pressure on their children during the decision making process about testing [15]. These issues raise the ethical problem of how health professionals can respect young adults’ developing autonomy [28–32]. Werner-Lin et al. [32] investigated genetic counsellors’ perspectives on counselling clients aged between 18 and 25 years, using an online survey: a primary challenge reported was navigating family dynamics in counselling sessions. However, our findings show that YA who were strongly influenced by their parents to be tested were less likely to feel anxious. This result may confirm that YA did not completely understand the implications of the genetic test but complied because of parental pressure, and potentially felt relieved of the responsibility to make their own decisions. An American study indicated that the current generation of YA have higher levels of student debt and are more likely to experience poverty and unemployment, while 53% of emerging adults aged 18–24 years currently lived with parents [33, 34]. This is also true in Italy, where 62.5% of YA aged 18–34 years live with their nuclear families [35, 36]. Living independently is one of the key developmental tasks of emerging adulthood [37]. If YA are co-resident with their parents, this could slow down the process of achieving autonomy as an adult. It is reasonable to hypothesise that this style of life has an impact on developmental tasks, reducing the autonomy of YA in their decision making. In fact, in our sample the number of PIQ who had been tested based on their own decision was significantly lower if compared to PEQ. However, genetic counsellors may have a responsibility to enable young people to challenge decisions made by their parents that may be inappropriate for them [38]; it may be that parents do not always make the best possible decision for their offspring, but usually one that is intended to support them. In the context of PST, where there is uncertainty about the potential harm and/or benefits, Cohen believes that the parent’s decision should prevail over their offspring’s decision [39]. However, with regard to the principle of decision-making by a surrogate Buchanan and Brock [40] provided data on the fact that there may be a failure by parents to make a decision in the best interests of their children. The evidence of this study highlights the need for a comprehensive, longitudinal counselling process with appropriate timing and setting, which supports ‘parent-to-offspring’ risk communication first and YA’s decision making about PST and risk management afterwards. This would include emphasising that disclosure of genetic risk is a gradual and dynamic process in the family, and where children are told at an early age, this should be followed with further age-appropriate information.

Strengths and limitations

The limited number of PIQ reduced the possibility of observing differences between groups about their experience of PST. This could be the result of difficulties in recruiting: only 39.3% of PIQ had accessed the questionnaire via the Internet, compared to 100% of PEQ. Another reason could be less interest in the Italian population regarding sharing information on medical issues via the Internet. Furthermore, the possibility of generalising the results of factor analysis could be hampered by the small sample size [41–45], particularly for the parent questionnaire. Moreover, almost all participants were variant-positive. It may be that potential participants who received negative test results were no longer sufficiently interested in the topic to respond, or perceived that the topic was not relevant to them. Additionally, another limitation could be that data were collected retrospectively and not at the time of PST. Moreover, the choice of statistical tests and the SPSS outcomes were assessed by all the authors, who are experienced researchers, to maximise the validity of the analysis.

Conclusions

In conclusion, there is much research to do on this topic, and the results presented here need to be more fully explored. However, the findings of this study could contribute to improving clinical practice. They indicate a need both for publicising the supportive and educational role of genetic services. It is therefore important to emphasise that young adults may benefit from a multistep approach for undergoing genetic testing, and parents need to be more informed that genetic counselling is a place where information is obtained and young adults can freely talk about the decision, regardless of whether they want to be tested or not.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the young adults and parents who participated in this study. We also kindly acknowledge all the administrators that give us the permission to post the recruitment messages in their Facebook group, and Twitter sites. LG was supported by the Grant from Regione Emilia-Romagna “Diagnostics advances in hereditary breast cancer (DIANE)” (PRUa1GR-2012-001).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41431-018-0262-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Evans JP, Skrzynia C, Burke W. The complexities of predictive genetic testing. BMJ. 2001;322:1052–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7293.1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beery TA, Williams JK. Risk reduction and health promotion behaviors following genetic testing for adult-onset disorders. Genet Test. 2007;11:111–23. doi: 10.1089/gte.2006.0527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quaid KA, Sims SL, Swenson MM, et al. Living at risk: concealing risk and preserving hope in Huntington disease. J Genet Couns. 2008;17:117–28. doi: 10.1007/s10897-007-9133-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baig SS, Strong M, Rosser E, et al. 22 Years of predictive testing for Huntington’s disease: the experience of the UK Huntington’s Prediction Consortium. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24:1396–402. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2016.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meissen GJ, Mastromauro CA, Kiely DK, et al. Understanding the decision to take the predictive test for Huntington disease. Am J Med Genet. 1991;39:404–10. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320390408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams JK, Schutte DL, Evers CA et al. Adults seeking presymptomatic gene testing for Huntington disease. J Nurs Scholarship. 1999; 31:109–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Borry P, Stultiens L, Nys H, et al. Presymptomatic and predictive genetic testing in minors: a systematic review of guidelines and position papers. Clin Genet. 2006;70:374–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richards FH. Predictive genetic testing of adolescents for Huntington disease: a question of autonomy and harm. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2008;146A:2443–6. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duncan RE, Gillam L, Savulescu J, et al. Reply to Richards: ‘Predictive genetic testing of adolescents for Huntington disease: a question of autonomy and harm’. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2008;146A:2447–8. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borry P, Evers-Kiebooms G, Cornel MC, et al. Genetic testing in asymptomatic minors: background considerations towards ESHG Recommendations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:711–9. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rindfuss R. The young adult years: diversity, structural change, and fertility. Demography. 1991;28:493–512. doi: 10.2307/2061419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patenaude AF, Dorval M, DiGianni LS, et al. Sharing BRCA1/2 test results with first-degree relatives: factors predicting who women tell. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:700–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.7541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bradbury AR, Dignam JJ, Ibe CN, et al. How often do BRCA mutation carriers tell their young children of the family’s risk for cancer? A study of parental disclosure of BRCA mutations to minors and young adults. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3705–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Der Meer LB, Van Duijn E, Wolterbeek R, et al. Adverse childhood experiences of persons at risk for Huntington’s disease or BRCA1/2 hereditary breast/ovarian cancer. Clin Genet. 2012;81:18–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Godino L, Turchetti D, Jackson L, et al. Impact of presymptomatic genetic testing on young adults: a systematic review. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24:496–503. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Godino L, Jackson L, Turchetti D, et al. Decision making and experiences of young adults undergoing presymptomatic genetic testing for familial cancer: a longitudinal grounded theory study. Eur J Hum Genet. 2018;26:44–53. doi: 10.1038/s41431-017-0030-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mann CJ. Observational research methods. Research design II: cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:54–60. doi: 10.1136/emj.20.1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: the tailored design method. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2014.

- 19.Gruppo di Lavoro congiunto Istat-FUB. Internet@Italia 2013: La popolazione italiana e l’uso di Internet. Roma: ISTAT-FUB; 2014.

- 20.Shiloh S, Avdor O, Goodman RM. Satisfaction with genetic counseling: Dimensions and measurement. Am J Med Genet. 1990;37:522–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320370419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruno M, Tommasi S, Stea B, et al. Awareness of breast cancer genetics and interest in predictive genetic testing: a survey of a southern Italian population. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:I48–54. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azzalini A. Inferenza statistica : una presentazione basata sul concetto di verosimiglianza. New York: Springer; 2001.

- 23.Tercyak KP, Peshkin BN, DeMarco TA, et al. Parent-child factors and their effect on communicating BRCA1/2 test results to children. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;47:145–53. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(01)00192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaiser HF. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika. 1974;39:31–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02291575. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Metcalfe A, Plumridge G, Coad J, et al. Parents’ and children’s communication about genetic risk: a qualitative study, learning from families’ experiences. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:640–6. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Metcalfe A, Coad J, Plumridge GM, et al. Family communication between children and their parents about inherited genetic conditions: a meta-synthesis of the research. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16:1193–200. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaff CL, Lynch E, Spencer L. Predictive testing of eighteen year olds: counseling challenges. J Genet Couns. 2006;15:245–51. doi: 10.1007/s10897-006-9028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duncan RE, Gillam L, Savulescu J, et al. ‘Holding your breath’: interviews with young people who have undergone predictive genetic testing for Huntington disease. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2007;143A:1984–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duncan RE, Gillam L, Savulescu J, et al. ‘You’re one of us now’: young people describe their experiences of predictive genetic testing for Huntington disease (HD) and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2008;148c:47–55. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duncan RE, Gillam L, Savulescu J et al. The challenge of developmentally appropriate care: predictive genetic testing in young people for familial adenomatous polyposis. Fam Cancer. 2010; 9: 27–35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Hamilton R, Williams JK, Bowers BJ, et al. Life trajectories, genetic testing, and risk reduction decisions in 18-39 year old women at risk for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. J Genet Couns. 2009;18:147–59. doi: 10.1007/s10897-008-9200-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Werner-Lin A, Ratner R, Hoskins LM, et al. A survey of genetic counselors about the needs of 18-25 year olds from families with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome. J Genet Couns. 2015;24:78–87. doi: 10.1007/s10897-014-9739-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pew Research Center. The boomerang generation: Feeling OK about living with mom and dad. 2012. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/files/2012/03/PewSocialTrends-2012-BoomerangGeneration.pdf. Accessed 4 Jan 2016.

- 34.Pew Research Center. A rising number of young adults live in their parents’ home. 2013. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/08/01/a-rising-share-of-young-adults-live-in-their-parents-home/. Accessed 4 Jan 2016.

- 35.Ferrari G, Rosina A, Sironi E. Beyond good intentions: the decision-making process of leaving the family of origin in Italy. Dondena Work Pap. 2014;60:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Istat. Giovani.Stat. 2016. http://dati-giovani.istat.it/Index.aspx. Accessed 10 Dec 2016.

- 37.Shanahan MJ. Pathways to adulthood in changing societies: variability and mechanisms in life course perspective. Annu Rev Sociol. 2000;26:667–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.667. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.American Society of Human Genetics Board of Directors, American College of Medical Genetics Board of Directors. Points to consider: ethical, legal, and psychosocial implications of genetic testing in children and adolescents. American Society of Human Genetics Board of Directors, American College of Medical Genetics Board of Directors. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57:1233–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen CB. Wrestling with the future: should we test children for adult-onset genetic conditions? Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 1998;8:111–30. doi: 10.1353/ken.1998.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buchanan A, Brock D. Deciding for others: the ethics of surrogate decision making. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1990.

- 41.Guilford PJ. Psychometric methods, 2nd ed. New York : McGraw-Hill; 1954.

- 42.Comrey AL, Lee HB. A first course in factor analysis. Psychology Press; 1973.

- 43.Gorsuch R. Factor analysis. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cattell RB. The scientific use of factor analysis in behavioral and life sciences. Boston, MA: Springer; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Grablowsky BJ. Multivariate data analysis. Tulsa. 1979.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.