Abstract

Quinoa has recently gained international attention because of its nutritious seeds, prompting the expansion of its cultivation into new areas in which it was not originally selected as a crop. Improving quinoa production in these areas will benefit from the introduction of advantageous traits from free-living relatives that are native to these, or similar, environments. As part of an ongoing effort to characterize the primary and secondary germplasm pools for quinoa, we report the complete mitochondrial and chloroplast genome sequences of quinoa accession PI 614886 and the identification of sequence variants in additional accessions from quinoa and related species. This is the first reported mitochondrial genome assembly in the genus Chenopodium. Inference of phylogenetic relationships among Chenopodium species based on mitochondrial and chloroplast variants supports the hypotheses that 1) the A-genome ancestor was the cytoplasmic donor in the original tetraploidization event, and 2) highland and coastal quinoas were independently domesticated.

Introduction

Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) is an emerging pseudocereal crop whose recent increase in popularity is primarily due to its highly nutritious seeds, which contain higher protein levels and a more balanced amino acid profile than most of the grass-cereals1. Quinoa is native to the Andean and Mediterranean-coastal climate zones of South America and consequently possesses many desirable agronomic traits, such as tolerance to harsh abiotic conditions, including frost and high soil salinity2; however, many traits are not suitable for large-scale agricultural production, especially as global quinoa cultivation expands into non-native areas to which quinoa is not adapted. For example, many quinoa accessions are prone to lodging, susceptible to fungal pathogens, sensitive to heat, or excessively branched and therefore suboptimal for mechanized, irrigated cropping systems. Although it was domesticated thousands of years ago3, efforts to develop the genomic tools needed to improve quinoa only began within the last 20 years. High-quality genome assemblies are now available for accessions representing the two major ecotypes: PI 6148864 (coastal ecotype) and ‘Real’5 (highland or Salares ecotype). In addition, chloroplast genome assemblies are available for three quinoa accessions: ‘Real’5, PI 5105506, and PI 4332327. These reference genome sequences can now be used to identify variants in related accessions and species that might be useful in quinoa breeding, as well as to help elucidate the evolutionary history of quinoa.

Quinoa is an allotetraploid (2n = 4x = 36) which arose as the result of the hybridization between A- and B-sub-genome diploid species between 3.3 and 6.3 million years ago4, possibly in North America. The A and B sub-genomes are also shared by the related tetraploid species C. berlandieri Moq. and C. hircinum Schrad., which, together with quinoa, form an interfertile group known as the allotetraploid goosefoot complex (ATGC). Long-range dispersal of the ancestral free-living ATGC eventually resulted in the appearance and domestication of quinoa in the Lake Titicaca Basin over 7,000 years ago8. In addition to quinoa, the ATGC was the source of at least three other cultigens: Mesoamerican vegetable huauzontle and pseudocereal chia roja (C. berlandieri ssp. nuttaliae)9; and the extinct staple pseudocereal of the North American Hopewell Culture, C. berlandieri ssp. jonesianum10. Free-living C. berlandieri and C. hircinum occupy a much larger geographic distribution than quinoa4 and have therefore naturally adapted to many of the environments into which quinoa production is expanding; thus, these species, as well as sympatric free-living C. quinoa ssp. melanospermum (known by indigenous peoples as Ajara), represent potential sources of advantageous traits that can be bred into cultivated quinoa varieties.

As an important step in characterizing the primary and secondary germplasm pools for quinoa, we report the de novo assembly of the complete mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes of the coastal accession PI 614886 and the identification of sequence variants in 13 additional accessions of quinoa, five accessions of C. berlandieri, two accessions of C. hircinum, and the diploid species C. pallidicaule Aellen. and C. suecicum Murr. (representing the A and B sub-genomes, respectively). This is the first report of an assembled mitochondrial genome for the genus. We show evidence that the A-sub-genome ancestor of quinoa was likely the maternal parent in the tetraploidization event, supporting the hypothesis that the initial polyploidization event likely occurred in the New World.

Results and Discussion

Mitochondrial genome assembly, annotation, and comparison

Unlike chloroplast genomes, plant mitochondrial genomes are highly variable among different species. As such, it is not possible to assemble complete mitochondrial genomes using purely read-mapping approaches. Here we assembled previously reported4 Illumina sequencing reads with the Assembly by Reduced Complexity (ARC)11 assembly pipeline seeded with a reference mitochondrial target from Beta vulgaris L.12 (sugar beet) and gap-filled with long sequencing reads from Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) to produce the first reported mitochondrial genome assembly in quinoa. The assembly is 315,003 bp in length, which is shorter than the reported mitochondrial sequences of B. vulgaris (368,801 bp)12, B. vulgaris ssp. maritima (sea beet; 364,950 bp), and Spinacia oleracea L. (spinach; 329,613 bp)13 – the only other species in the Amaranthaceae with reported mitochondrial sequences.

The assembled mitochondrial sequence was annotated with 30 protein-coding genes, 21 tRNA genes, and 3 rRNA genes (Fig. 1a; Table 1), which is similar to the 29 and 29 protein-coding genes, 25 and 24 tRNA genes, and 5 and 3 rRNA genes reported in the mitochondrial genomes of B. vulgaris12 and S. oleracea13, respectively. Most annotated genes are supported by strong evidence of expression (Fig. 1a). Twenty-eight (93.3%) of the protein-coding genes overlap with predicted open reading frames (ORFs) (Fig. 1a). A majority of the predicted ORFs (73 out of 112; 65.2%) do not overlap with any annotated genes; however, most of these ORFs show no evidence of expression, suggesting that they are false predictions (Fig. 1a). The quinoa mitochondrial sequence does not lack any genes common to the other sequenced Amaranthaceae mitochondrial genomes (Table 1), suggesting that the sequence is likely complete.

Table 1.

Protein-coding, tRNA, and rRNA genes annotated in the quinoa mitochondrial genome, in comparison to related species.

| Gene | B. vulgaris ssp. maritima | B. vulgaris | C. quinoa | S. oleracea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| atp1 | + | + | + | + |

| atp4 | − | − | + | + |

| atp6 | + | + | + | + |

| atp8 | + | + | + | + |

| atp9 | + | + | + | + |

| ccmB/ccb206 | + | + | + | + |

| ccmC | − | − | + | + |

| ccmFC/ccb438 | + | + | + | + |

| ccmFN/ccb577 | + | + | + | + |

| cob | + | + | + | + |

| cox1 | + | + | + | + |

| cox2 | + | + | + | + |

| cox3 | + | + | + | + |

| mat-r | + | + | + | + |

| nad1 | ++ | + | + | − |

| nad2 | + | + | + | + |

| nad3 | + | + | + | + |

| nad4 | + | + | + | + |

| nad4L | + | + | + | + |

| nad5 | + | + | + | + |

| nad6 | + | + | + | + |

| nad7 | + | + | + | + |

| nad9 | + | + | + | + |

| petG | + | − | − | − |

| rpl5 | + | + | + | + |

| rps12 | + | + | + | + |

| rps13 | + | + | + | + |

| rps3 | + | + | + | + |

| rps4 | + | + | + | + |

| rps7 | ++ | + | + | + |

| sdh4 | + | − | − | − |

| tatC | + | − | + | + |

| rrn5 | + | + | + | + |

| rrn18 | + | + | + | + |

| rrn26 | +++ | +++ | + | + |

| tRNA-Asn | + | + | + | + |

| tRNA-Asp | + | + | + | + |

| tRNA-Cys | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ |

| tRNA-Gln | + | + | + | + |

| tRNA-Glu | + | + | + | + |

| tRNA-Gly | + | + | + | + |

| tRNA-His | + | + | + | ++ |

| tRNA-Ile | + | ++ | − | + |

| tRNA-Leu | − | − | − | + |

| tRNA-Lys | + | + | + | + |

| tRNA-Met | +++++ | +++++ | +++++ | +++ |

| tRNA-Phe | + | + | + | +++ |

| tRNA-Pro | + | ++ | + | + |

| tRNA-Ser | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| tRNA-Trp | + | + | + | + |

| tRNA-Tyr | + | + | + | + |

| tRNA-Val | + | + | − | − |

+The number of copies of a gene present in each mitochondrial genome.

−The absence of a gene.

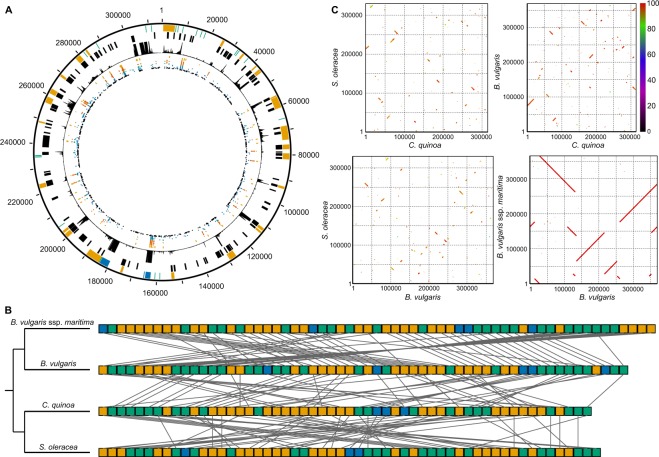

Figure 1.

Structure of the mitochondrial genome in quinoa and related species. (A) Features of the mitochondrial genome assemblies in quinoa. Starting from the outside, tracks represent position (bp), annotated genes (orange, CDS; blue, tRNA; green, rRNA), predicted ORFs, RNA-seq read depth, and SNPs (black, C. pallidicaule and C. suecicum; blue, C. berlandieri; green, C. hircinum; brown, highland quinoa; orange, coastal quinoa). (B) Linear order of genes (orange, CDS; blue, tRNA; green, rRNA) in the mitochondrial genomes of quinoa and related species. Species are arranged according to the accepted organismal phylogeny, with lines connecting genes with the same annotation. Boxes are not proportional to actual gene length. (C) Dotplot visualization of nucleotide-by-nucleotide comparisons of the mitochondrial sequence from Amaranthaceae species. Axes are reported in bp. Scale bar reports percent nucleotide identity.

The quinoa mitochondrial genome was annotated with one copy each of the 5S, 18S, and 26S rRNA genes (Fig. 1a, Table 1). Additionally, a region of the mitochondrial sequence from approximately 305–308 kb was annotated as containing a fragment of the 26S rRNA gene, and BLAST analysis of this region showed high sequence similarity to the 26S rRNA gene from several other species, including B. vulgaris, which contains three annotated 26S rRNA genes. This region shows extremely high levels of expression that is representative of the expression seen from the other annotated rRNA genes (Fig. 1a). Thus, this sequence likely represents a second, possibly fragmented copy of the 26S rRNA gene which is still expressed in quinoa.

The quinoa mitochondrial genome also contains two tRNACys genes (trnC-GCA): one copy, located near position 8.4 kb, is homologous to the native trnC1-GCA gene from B. vulgaris; the other copy, located near position 311.1 kb, is homologous to the two novel copies of trnC2-GCA from B. vulgaris. The trnC2-GCA gene from B. vulgaris had not previously been identified in other higher plants12; its presence in the quinoa mitochondrial genome suggests that this gene is shared among Amaranthaceae species.

Although there are few differences in gene content among the sequenced Amaranthaceae mitochondrial genomes (Table 1), there are substantial differences in gene order (Fig. 1b). Not surprisingly, there is greater conservation of gene order within species (for example, between B. vulgaris and B. vulgaris ssp. maritima) than between species (for example, between quinoa and B. vulgaris or S. oleracea). Similar patterns were also observed at the overall nucleotide level, in which a relatively small number of rearrangements have shuffled large sequences of DNA within B. vulgaris, but a much higher number of rearrangements have resulted in low levels of sequence collinearity between quinoa and the other Amaranthaceae species (Fig. 1c). Such extensive rearrangement has been observed in the mitochondrial genomes of other plant families14 but is in contrast to the high degree of conservation observed in mitochondrial genomes of animals15,16.

To assess variation within Chenopodium, re-sequencing data from 13 additional quinoa accessions; five and two accessions of the related tetraploid species C. berlandieri and C. hircinum, respectively; and one accession each of the A-genome diploid C. pallidicaule and the B-genome diploid C. suecicum were mapped onto the reference PI 614886 mitochondria assembly. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and insertion/deletion variants (InDels) were identified in each re-sequencing accession relative to the PI 614886 reference assembly (Table 2). As expected, more variants in the mitochondria were identified in the diploid species C. pallidicaule and C. suecicum (491 and 626 SNPs, and 188 and 203 InDels, respectively) than in the tetraploids (with an average of 90 SNPs and 83 InDels). We acknowledge that sequence rearrangements such as those described above can affect the efficiency of read mapping and variant calling; however, these rearrangements, which we anticipate to be few in number within Chenopodium, are difficult to identify using re-sequencing data.

Table 2.

Variants in the mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes of Chenopodium species.

| Species | Accession | Mitochondria | Chloroplast | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | INDEL | SNP | INDEL | ||

| C. quinoa | 0654 | 109 | 91 | 69 | 28 |

| C. quinoa | Cherry Vanilla | 72 | 87 | 33 | 23 |

| C. quinoa | Chucapaca | 46 | 72 | 16 | 37 |

| C. quinoa | CICA-17 | 60 | 100 | 36 | 23 |

| C. quinoa | G-205-95DK | 84 | 66 | 0 | 0 |

| C. quinoa | Ku-2 | 90 | 72 | 0 | 0 |

| C. quinoa | Kurmi | 83 | 91 | 36 | 24 |

| C. quinoa | Ollague | 73 | 83 | 35 | 23 |

| C. quinoa | Pasankalla | 70 | 81 | 25 | 13 |

| C. quinoa | PI 634921 | 56 | 65 | 17 | 36 |

| C. quinoa | Real | 78 | 90 | 37 | 24 |

| C. quinoa | Regalona | 85 | 68 | 3 | 0 |

| C. quinoa | Salcedo INIA | 74 | 87 | 33 | 23 |

| C. berlandieri subsp. nuttalliae | PI 568156 | 198 | 97 | 63 | 30 |

| C. berlandieri var. boscianum | BYU 937 | 151 | 95 | 52 | 29 |

| C. berlandieri var. macrocalycium | PI 666279 | 85 | 70 | 60 | 28 |

| C. berlandieri var. sinuatum | Ames 33013 | 146 | 89 | 50 | 30 |

| C. berlandieri var. zschackei | BYU 1314 | 86 | 81 | 73 | 33 |

| C. hircinum | BYU 1101 | 74 | 80 | 54 | 21 |

| C. hircinum | BYU 566 | 72 | 86 | 25 | 14 |

| C. pallidicaule | Ames 13221 | 491 | 188 | 709 | 145 |

| C. suecicum | 328/6 | 626 | 203 | 1181 | 221 |

Consensus sequences were generated from the mapped reads for each re-sequenced accession, and simple sequence repeats (SSRs) were identified in the consensus sequences as well as in the PI 614886 reference sequence. Similar numbers of SSRs were identified in all accessions, with 50 SSR motifs identified in PI 614886 and an average of 48 SSR motifs identified in each accession (Supplementary Table S2). Approximately half of all repeats in each accession are tetranucleotide repeats; no hexanucleotide repeats were identified in any of the accessions (Supplementary Table S2).

Chloroplast genome assembly, annotation, and comparison

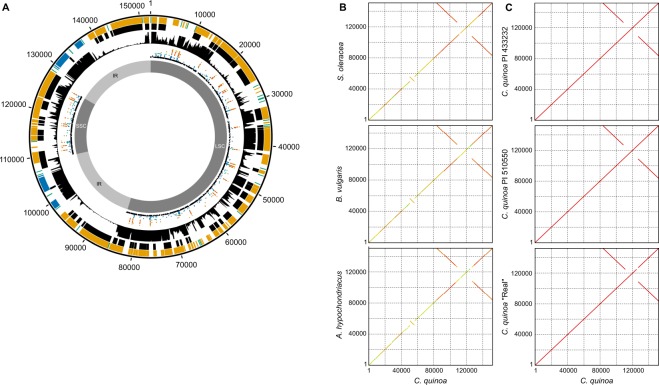

We also used previously reported4 Illumina and PacBio reads to assemble the chloroplast genome of quinoa accession PI 614886 into a single circular contig 152,079 bp in length, which is almost identical to the lengths of chloroplast assemblies reported in other quinoa accessions (152,075 in PI 5105506; 152,099 in PI 4332327; and 152,282 in ‘Real’5), and slightly longer than those reported in other closely related Amaranthaceae species (149,635 in B. vulgaris17; 150,518 in A. hypochondriacus18; and 150,725 in S. oleracea19). The assembly contains the large (LSC) and small (SSC) single-copy regions separated by two inverted repeats (IR) that typically characterize chloroplast sequences (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2.

Structure of the chloroplast genome in quinoa and related species. (A) Features of the chloroplast genome assemblies in quinoa. Starting from the outside, tracks represent position (bp), annotated genes (orange, CDS; blue, tRNA; green, rRNA), predicted ORFs, RNA-seq read depth, SNPs (black, C. pallidicaule and C. suecicum; blue, C. berlandieri; green, C. hircinum; brown, highland quinoa; orange, coastal quinoa); and the positions of the LSC, SSC, and IR regions. (B,C) Dotplot visualization of nucleotide-by-nucleotide comparisons of the chloroplast sequence from Amaranthaceae species (B) and quinoa accessions (C). Axes are reported in bp.

The sequence was annotated with 86 protein-coding, 31 tRNA, and 8 rRNA genes (Fig. 2a, Table 3). Most annotated genes are supported by strong evidence of expression (Fig. 2a); however, only 40 (46.5%) of the protein-coding genes overlap perfectly with predicted ORFs, whereas 30 (34.9%) genes do not overlap with any predicted ORFs (Fig. 2a). Most (27) of the genes in the latter category, however, are shorter than the minimum length used for ORF prediction (300 bp). One of the three genes longer than 300 bp that does not overlap with any predicted ORFs, atpF, contains an intron, which may explain the absence of a predicted ORF. The other two genes are two copies of rps12 located in the inverted repeats near positions 96.0 kb and 138.8 kb. These genes appear to be transpliced with a separate mRNA transcript produced from a fragment of rps12 located at approximately 68.9 kb. Nine genes (10.5%) overlap only partially with predicted ORFs. In some cases, such as for ndhA and rpl16, this is likely due to the presence of introns disrupting the ORF. In other cases, such as for ndhD and psbC, it is due to the use of alternative translational start codons. At least one gene, rpl23, appears to be a pseudogene. Two sequences homologous to rpl23 are present in the inverted repeats of the quinoa chloroplast genome at positions 84.5 kb and 150.8 kb. However, both sequences contain internal stop codons; hence, no open reading frames longer than 300 bp were predicted in these regions (Fig. 2a). Pseudogenization of rpl23 has been reported in the chloroplast genomes of quinoa and other Amaranthaceae species6,20.

Table 3.

Protein-coding, tRNA, and rRNA genes annotated in the quinoa chloroplast genome, in comparison to related species.

| Gene | A. hypochondriacus | B. vulgaris | C. quinoa | S. oleracea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| accD | + | + | + | + |

| atpA | + | + | + | + |

| atpB | + | − | + | + |

| atpE | + | + | + | + |

| atpF | + | + | + | + |

| atpH | + | + | + | + |

| atpI | + | + | + | + |

| ccsA | + | + | + | − |

| cemA | + | + | + | + |

| clpP | + | + | + | + |

| infA | + | + | + | + |

| matK | + | + | + | − |

| nad2 | − | + | − | − |

| ndhA | + | + | + | + |

| ndhB | + | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| ndhC | + | + | + | + |

| ndhD | + | + | + | + |

| ndhE | + | + | + | + |

| ndhF | + | + | + | + |

| ndhG | + | + | + | + |

| ndhH | + | + | + | + |

| ndhI | + | + | + | + |

| ndhJ | + | + | + | + |

| ndhK | + | + | + | + |

| petA | + | + | + | + |

| petB | − | + | + | + |

| petD | + | + | + | + |

| petG | + | + | + | + |

| petL | + | + | + | + |

| petN | + | + | + | − |

| psaA | + | + | + | + |

| psaB | + | − | + | + |

| psaC | + | + | + | + |

| psaI | + | + | + | + |

| psaJ | + | + | + | + |

| psbA | + | + | + | + |

| psbB | + | − | + | + |

| psbC | + | + | + | + |

| psbD | + | + | + | + |

| psbE | + | + | + | + |

| psbF | + | + | + | + |

| psbH | + | + | + | + |

| psbI | + | + | + | + |

| psbJ | + | + | + | + |

| psbK | + | + | + | + |

| psbL | − | + | + | + |

| psbM | + | + | + | + |

| psbN/pbf1 | + | + | + | + |

| psbT | + | + | + | + |

| psbZ | + | + | + | − |

| psi | − | + | − | − |

| rbcL | + | + | + | + |

| rpl14 | + | + | + | + |

| rpl16 | ++ | + | + | + |

| rpl2 | + | ++ | ++ | + |

| rpl20 | + | + | + | + |

| rpl22 | + | + | + | + |

| rpl23 | − | ++ | ++ | − |

| rpl32 | + | + | + | + |

| rpl33 | ++ | + | + | + |

| rpl36 | − | − | + | + |

| rpoA | + | + | + | + |

| rpoB | + | + | + | + |

| rpoC1 | + | + | + | + |

| rpoC2 | + | + | + | + |

| rps2 | + | + | + | + |

| rps12 | ++ | − | ++ | ++ |

| rps14 | − | + | + | + |

| rps15 | + | + | + | + |

| rps16 | + | + | + | + |

| rps18 | + | + | + | + |

| rps19 | − | + | + | + |

| rps2 | + | + | + | + |

| rps3 | + | + | + | + |

| rps4 | + | + | + | + |

| rps7 | + | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| rps8 | + | + | + | + |

| ycf1 | − | ++ | + | + |

| ycf2 | − | ++ | ++ | + |

| ycf3 | − | + | + | ++ |

| ycf4 | + | + | + | + |

| ycf5 | − | − | − | + |

| ycf6 | − | − | − | + |

| ycf9 | − | − | − | + |

| tRNA-Ala | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| tRNA-Arg | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| tRNA-Asn | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| tRNA-Asp | + | + | + | + |

| tRNA-Cys | + | + | + | + |

| tRNA-Gln | + | + | + | + |

| tRNA-Glu | + | + | + | + |

| tRNA-Gly | + | ++ | + | ++ |

| tRNA-His | + | + | + | + |

| tRNA-Ile | − | ++++ | − | ++++ |

| tRNA-Leu | +++ | ++++ | +++ | ++++ |

| tRNA-Lys | − | + | − | + |

| tRNA-Met | ++++ | ++ | ++++ | ++ |

| tRNA-Phe | + | + | + | + |

| tRNA-Pro | + | + | + | + |

| tRNA-Ser | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| tRNA-Thr | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| tRNA-Trp | + | + | + | + |

| tRNA-Tyr | + | + | + | + |

| tRNA-Val | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ |

| rrn4.5 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| rrn16 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| rrn23 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| rrn5 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

+The number of copies of a gene present in each chloroplast genome.

−The absence of a gene.

The quinoa chloroplast sequence does not lack any genes common to the A. hypochondriacus, B. vulgaris, and S. oleracea chloroplast genomes, nor does it have any unique genes not found in the chloroplast sequences of these species. Indeed, there is a high degree of sequence conservation among chloroplast genomes of the Amaranthaceae species, with the main structural difference between quinoa and the other species being a small inversion (Fig. 2b) that has been previously reported in quinoa6. No major structural variations were observed among all the quinoa chloroplast genome assemblies (Fig. 2c), suggesting that the observed inversion relative to other Amaranthaceae species is not due to an assembly error. Despite the absence of major structural variation among the quinoa accessions, dotplot visualization of nucleotide-level comparisons among the quinoa chloroplast assemblies revealed a region near position 125 kb in ‘Real’ that did not match the corresponding region in PI 614886 (Fig. 2c, bottom panel). A BLAST analysis of each previously reported quinoa assembly against the PI 614886 assembly confirmed that the non-homologous sequence in this region was found only in the ‘Real’ assembly (Supplementary Fig. S1a). This region is within the predicted ycf1 gene. A BLAST search of the ycf1 sequence from Arabidopsis thaliana indicated that the ycf1 gene is complete in the PI 614886 assembly (Supplementary Fig. S1b, top track) but is missing approximately 2 kb of sequence in the middle of the gene in the ‘Real’ assembly (Supplementary Fig. S1b, middle track). Additional BLAST searches indicated that the ‘Real’ assembly contains the ndhF gene nested within ycf1. This ndhF gene was not identified in the consensus sequence (Supplementary Fig. S1b, bottom track) or the mapped raw reads (Supplementary Fig. S1a, inner track) of our re-sequenced ‘Real’ accession. The ‘Real’ accession is more appropriately considered an ecotype, as it represents a collection of landraces from the Salares region of the Bolivian Altiplano. Thus, although the discrepancy between the published ‘Real’ chloroplast assembly and our re-sequencing data may be due to assembly errors, it is also possible that it represents sequence variation among ‘Real’ genotypes.

Data from the re-sequenced accessions was mapped onto the quinoa reference (PI 614886) chloroplast assembly, as was done with the mitochondrial sequence, and SNPs and InDels were identified in each re-sequencing accession relative to the PI 614886 reference assembly (Table 2). As was observed with the mitochondria, more variants were identified in the diploid species C. pallidicaule and C. suecicum (709 and 1181 SNPs, and 145 and 221 InDels, respectively) than in the tetraploids (with an average of 36 SNPs and 22 InDels). Collectively, 301 and 1,650 unique SNP positions were identified in the tetraploids and diploids, respectively; 56 (19%) of the tetraploid SNP positions also contained SNPs in at least one of the diploids, whereas 42 (3%) of the diploid SNP positions also contained SNPs in at least one of the tetraploids (Fig. 2a; to avoid confounding results, SNPs identified in the highly similar IR regions were excluded). No SNPs and/or very few InDels were identified in the chloroplast sequences of three quinoa accessions: ‘G-205-95DK’, ‘Ku-2’, and ‘Regalona’. All three accessions and the reference accession PI 614886 are of the coastal type (Supplementary Table S1), which may explain the low level of chloroplast sequence variation in these accessions.

As was done for the mitochondria, consensus chloroplast sequences were generated from the mapped reads for each re-sequenced accession, and simple sequence repeats (SSRs) were identified in the consensus PI 614886 reference chloroplast sequence. Similar numbers of SSRs were identified in all accessions, with 14 SSR motifs identified in PI 614886 and an average of 15 SSR motifs in each accession (Supplementary Table S3). As with the mitochondria, tetranucleotide repeats were the most common type identified in the chloroplast, making up approximately 40% of all repeats. Two accessions of C. berlandieri contained hexanucleotide repeats.

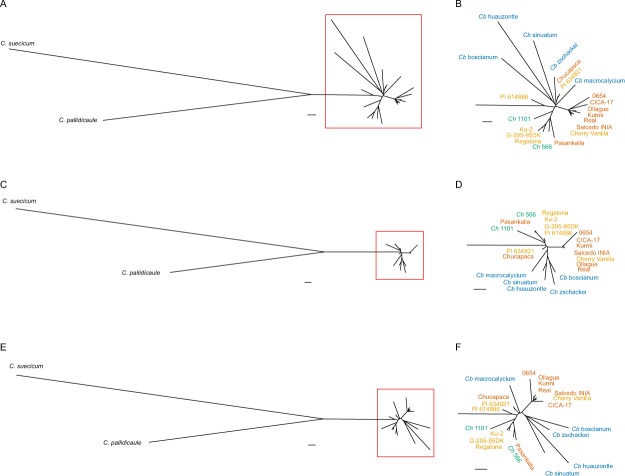

Phylogenetic relationships

Phylogenetic relationships among Chenopodium species based on variants in the mitochondria (Fig. 3a,b), chloroplast (Fig. 3c,d), and combined mitochondria/chloroplast (Fig. 3e,f) illustrate a number of relationships that are concordant with previous analyses of nuclear genome sequence data4. The two diploid species, C. pallidicaule (A-genome group) and C. suecicum (B-genome group) form the ancestral root of the tree from which the AABB ATGC tetraploids are derived. The A-genome ancestor is closer to the tetraploids, suggesting it was the cytoplasmic donor – and hence the likely maternal parent – in the original polyploidization event. Various accessions of C. berlandieri (blue text), the North American free-living species, are positioned more basally relative to the cultivated South American accessions of quinoa and the two accessions of the free-living South American taxon C. hircinum (green text). In general, the quinoas fall into two main groups: highland Andean (brown text) and a more distant branch consisting mostly of coastal ecotypes (orange text) as well as the Altiplano variety ‘Pasankalla’ and the two C. hircinum accessions. The distal placement of C. hircinum accessions on the coastal branch in all three trees suggests these are not ancestral to the Andean quinoas and may be representative of either ancestral or introgressive relationships with the coastal quinoa germplasm, as was also observed in the nuclear genome-based analysis4. Consequently, cytoplasmic DNA sequencing provides additional support for the hypothesis of separate Andean and Pacific coastal domestication events of South American goosefoot/quinoa.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic relationships among Chenopodium species based on variants in the mitochondria (A,B), chloroplast (C,D), and combined mitochondria/chloroplast (E,F). Networks displayed in (B), (D), and (F) are enlarged from the red-boxed regions shown in (A), (C), and (E), respectively. Black text, C. pallidicaule and C. suecicum; blue text, C. berlandieri (Cb); green text, C. hircinum (Ch); brown, highland quinoa; orange, coastal quinoa. Scale bar, 0.01 substitutions per site.

Interestingly, the Andean variety Chucapaca and the coastal line PI 634921 (origin, Valdivia, Los Rios Region, Chile) were both positioned basally with accessions of C. berlandieri instead of with other accessions within their respective ecotype clades. It is tempting to speculate that introgression occurred with C. berlandieri at some point in their histories; however, nuclear genome analysis clearly groups these lines with other quinoas of their respective ecotypes4.

Methods

Mitochondrial genome assembly and annotation

We used the Assembly by Reduced Complexity (ARC)11 pipeline seeded with a reference mitochondrial target from B. vulgaris to assemble the mitochondrial genome of quinoa accession PI 614886. In brief, the ARC assembly pipeline used Bowtie221 to align 12 million previously reported4 Illumina read pairs to a B. vulgaris mitochondrial target reference (NC_002511.2). Reads with high quality matches to the reference were extracted and assembled into quinoa-specific contigs using the SPAdes assembler22. The ARC pipeline was then used to extend the assembled quinoa mitochondrial contigs using four (numcycles = 4) successive rounds of mapping and re-assembly. Since mitochondria read depth should be significantly higher than nuclear genome read depth, only contigs with read depth >20 × (n = 18) were selected for gap-filling and circularization. PacBio long reads greater than 15 kb in length (n = 100,000) were used to fill gaps between contigs using the program PBJelly, a subprogram of PBSuite23. Visual inspection of the linear genome identified overlapping edges which were then stitched together to produce the final circular mitochondrial genome. Lastly, the mitrochondrial assembly was polished by re-mapping the same 12 million Illumina read pairs using the CLC Genomics Workbench, removing all unpaired reads (which likely occurred due to homology with nuclear genome sequences), and generating a final consensus sequence.

A consensus-corrected mitochondrial genome for each of the previously sequenced4 accessions of quinoa, C. berlandieri, C. hircinum, C. pallidicaule, and C. suecicum (Supplementary Table S1) was developed by mapping 12 million paired-end Illumina reads to the reference quinoa PI 614886 mitochondrial genome using the CLC Genomics Workbench and default parameters, with the exception that the length fraction and similar fractions were increased to 0.7 and 0.9, respectively. The mapped reads were then realigned to improve local alignment, followed by majority rule consensus sequence extraction for each accession.

The assembled quinoa mitochondrial genome was annotated using GeSeq24, selecting the options to perform tRNAscan-SE and BLAT using the NCBI RefSeq sequences for B. vulgaris and S. oleracea. ORFs with a minimum length of 300 bp were predicted using ORFfinder from NCBI25.

Chloroplast genome assembly and annotation

We identified in the previously published genome assembly of the quinoa accession PI 6148864 a contig (unitig_5592) that consisted of a single contiguous sequence completely encompassing the IRa, SSC, and IRb regions of the chloroplast genome, as well as significant portions of the LSC region. The missing portion of the LSC was assembled using previously reported4 Illumina short reads and the ARC assembly pipeline seeded with the S. oleracea chloroplast genome sequence (NC_002202.1), as described above for the mitochondrial assembly. The ARC assembly pipeline produced a single contig which encompassed the missing LSC region (82,805 bp) that overlapped both ends of unitig_5592 which when spliced together produced a single circular molecule representing the complete quinoa chloroplast genome.

A consensus-corrected chloroplast genome for each of the related accessions (Supplementary Table S1) was developed by mapping 6 million paired-end Illumina reads to the reference quinoa chloroplast genome using the CLC Genomics Workbench, as described above for the mitochondrial genome.

The assembled quinoa chloroplast genome was annotated using GeSeq, selecting the options to perform HMMER profile search (chloroplast CDS and rRNA), tRNAscan-SE, and BLAST using the MPI-MP chloroplast references, while leaving all other default settings. ORFs with a minimum length of 300 bp were predicted using ORFfinder.

Identification of SNPs, InDels, and SSRs

Microsatellites, or simple sequence repeats (SSRs), were identified using MISA26. We followed standard thresholds for identifying chloroplast and mitochondrial SSRs27,28, specifically a minimum stretch of 12 for mono-, 6 for di-, 4 for tri- and 3 for tetra-, penta- and hexa-nucleotide repeats and a minimum distance of 100 bp between compound SSRs.

SNPs and InDels were identified by aligning reads to the reference genome using BWA-MEM29 for each of the accessions. SNPs and InDels were identified using the Genome Analysis Tool Kit HaplotypeCaller (GATK-HC)30. A small number of SNPs were identified when mapping reads of PI 614886 to the reference PI 614886 assemblies, mainly because of the mapping of single, unpaired reads that likely had homology with nuclear sequences. Because these positions do not represent true variants, all positions for which a SNP was identified in PI 614886 were removed from variant calls in all other accessions.

Genome visualization

Circular visualization of the chloroplast and mitochondrial genome assemblies of PI 614886 was performed using Circa. CDS, tRNA, and rRNA features were plotted from the GeSeq annotations, and ORF features were plotted from the ORFfinder predictions, as described above. Read depth was calculated from RNA-seq reads generated from several quinoa tissues, as previously described4. Briefly, reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic31 and mapped to the PI 614886 chloroplast and mitochondrial genome assemblies using TopHat32. Read depth at each nucleotide position was calculated using SAMtools mpileup. SNP positions in the re-sequenced accessions were plotted from the variant calling files, as described above.

Comparison to previously sequenced genomes

Previously reported mitochondrial assemblies were downloaded for B. vulgaris subsp. vulgari12 (GenBank accession NC_002511.2), B. vulgaris subsp. maritima (Genbank accession NC_015099.1) and S. olerace13 (GenBank accession NC_035618.1). The genomes were compared using the default settings in nucmer from the mummer package33.

Previously published chloroplast assemblies were downloaded for A. hypochondriacus18 (GenBank accession NC_030770.1), B. vulgaris17 (GenBank accession KJ081864.1), and S. oleracea19 (GenBank accession AJ400848.1), and for quinoa accessions PI 4332327 (GenBank accession KY419706), PI 5105506 (GenBank accession KY635884), and ‘Real’5 (contig NSDK01003185.1 from GenBank accession NSDK00000000.1). Nucleotide-level comparisons of these genomes were performed using the default settings in nucmer. Further comparisons of the previously published quinoa chloroplast genomes to that of PI 614886 were performed using the CGView Comparison Tool34. In order to conduct an appropriate comparison of these genome sequences, each was annotated using GeSeq, as described above. The A. thaliana ycf1 (GenBank accession NC_000932.1, nucleotides 129244-123884) and ndhF (Genbank accession NC_000932.1, nucleotides 112638-110398) genes were compared to the PI 614886 and ‘Real’ chloroplast assemblies, as well as to the ‘Real’ consensus sequence reported herein, using BLASTn. Results were visualized using Kablammo35, showing only hits with e-value < 1e-10.

Phylogenetic network analysis

VCF files created by mapping re-sequencing reads to the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes, as described above, were filtered with custom Perl scripts to identify SNPs with quality scores of at least 200. Phylogenetic networks for the chloroplast, mitochondrial, and combined chloroplast and mitochondrial SNPs were then computed with SplitsTree36 using an uncorrected P distance algorithm and the Neighbor-Net neighboring network.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge David Brenner (USDA-NPGS, Ames, IA), Eulogio de la Cruz (ININ, Ocoyoacac, Mexico), Daniel Bertero (UBA, Buenos Aires, Argentina), Helena Storchova (Institute of Experimental Botany, Prague, Czech Republic), Francisco Fuentes (Pontificia Universidad Catolica, Santiago, Chile) and Angel Mujica (Universidad del Altiplano, Puno, Peru) for taxonomic suggestions and seed contribution. This research was funded by the Holmes Family Foundation.

Author Contributions

P.J.M. assembled the genome sequences; L.C., D.E.J., and B.J.C. annotated the sequences; L.C. identified sequence variants; D.J.L. performed phylogenetic network analysis; D.E.J. made figures and wrote the manuscript; P.J.M., L.C., M.T., E.N.J., and D.E.J. conceived the research; all authors read and approved the manuscript.

Data Availability

All raw data were previously reported4. The quinoa chloroplast and mitochondrial genome assemblies and annotations have been uploaded to NCBI under GenBank accession numbers MK159176 and MK182703.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-36693-6.

References

- 1.Gordillo-Bastidas E, Díaz-Rizzolo DA, Roura E, Massanés T, Gomis R. Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd), from nutritional value to potential health benefits: an integrative review. Journal of Nutrition & Food Sciences. 2016;6:1000497. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobsen S-E, Mujica A, Jensen C. The resistance of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) to adverse abiotic factors. Food Reviews International. 2003;19:99–109. doi: 10.1081/FRI-120018872. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bazile D, Jacobsen S-E, Verniau A. The global expansion of quinoa: trends and limits. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2016;7:622. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jarvis DE, et al. The genome of Chenopodium quinoa. Nature. 2017;542:307. doi: 10.1038/nature21370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zou C, et al. A high-quality genome assembly of quinoa provides insights into the molecular basis of salt bladder-based salinity tolerance and the exceptional nutritional value. Cell Research. 2017;27:1327–1340. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabah SO, et al. Plastome sequencing of ten nonmodel crop species uncovers a large insertion of mitochondrial DNA in cashew. The Plant Genome. 2017;10:0. doi: 10.3835/plantgenome2017.03.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong S-Y, et al. Complete chloroplast genome sequences and comparative analysis of Chenopodium quinoa and C. album. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2017;8:1696. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson H. Quinua biosystematics II: free-living populations. Economic Botany. 1988;42:478–494. doi: 10.1007/BF02862792. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson HD, Heiser CB., Jr. The origin and evolutionary relationships of ‘huauzontle’ (Chenopodium nuttalliae Safford), domesticated chenopod of Mexico. American Journal of Botany. 1979;66:198–206. doi: 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1979.tb06215.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith BD. Chenopodium berlandieri ssp. jonesianum: evidence for a Hopewellian domesticate from Ash Cave, Ohio. Southeastern. Archaeology. 1985;4:107–133. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunter, S. S. et al. Assembly by Reduced Complexity (ARC): a hybrid approach for targeted assembly of homologous sequences. bioRxiv 014662, 10.1101/014662 (2015).

- 12.Kubo T, et al. The complete nucleotide sequence of the mitochondrial genome of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.) reveals a novel gene for tRNACys(GCA) Nucleic Acids Research. 2000;28:2571–2576. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.13.2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai X, et al. The complete mitochondrial genome sequence of spinach, Spinacia oleracea L. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2017;2:339–340. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2017.1334518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asaf S, et al. Mitochondrial genome analysis of wild rice (Oryza minuta) and its comparison with other related species. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0152937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boore J. Animal mitochondrial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1767–1780. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.8.1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Du Y, Zhang C, Dietrich CH, Zhang Y, Dai W. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genomes of Maiestas dorsalis and Japananus hyalinus (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) and comparison with other Membracoidea. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:14197. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14703-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li H, et al. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris ssp. vulgaris). Mitochondrial. DNA. 2014;25:209–211. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2014.883611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaney L, Mangelson R, Ramaraj T, Jellen EN, Maughan PJ. The complete chloroplast genome sequences for four Amaranthus species (Amaranthaceae) Applications in Plant Sciences. 2016;4:1600063. doi: 10.3732/apps.1600063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmitz-Linneweber C, et al. The plastid chromosome of spinach (Spinacia oleracea): complete nucleotide sequence and gene organization. Plant Molecular Biology. 2001;45:307–315. doi: 10.1023/A:1006478403810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park J-S, Choi I-S, Lee D-H, Choi B-H. The complete plastid genome of Suaeda malacosperma (Amaranthaceae/Chenopodiaceae), a vulnerable halophyte in coastal regions of Korea and Japan. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2018;3:382–383. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2018.1437822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nature Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bankevich A, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. Journal of Computational Biology. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.English AC, et al. Mind the gap: upgrading genomes with Pacific Biosciences RS long-read sequencing technology. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e47768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tillich M, et al. GeSeq - versatile and accurate annotation of organelle genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W6–W11. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wheeler D, et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:28–33. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thiel T, Michalek W, Varshney RK, Graner A. Exploiting EST databases for the development and characterization of gene-derived SSR-markers in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2003;106:411–422. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sablok G, et al. ChloroMitoSSRDB 2.00: more genomes, more repeats, unifying SSRs search patterns and on-the-fly repeat detection. Database. 2015;2015:bav084. doi: 10.1093/database/bav084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar M, Kapil A, Shanker A. MitoSatPlant: mitochondrial microsatellites database of viridiplantae. Mitochondrion. 2014;19:334–337. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv:1303.3997v1 [q-bio.GN] (2013).

- 30.McKenna A, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Research. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–1111. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurtz S, et al. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biology. 2004;5:R12. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-2-r12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grant JR, Arantes AS, Stothard P. Comparing thousands of circular genomes using the CGView Comparison Tool. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:202. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wintersinger JA, Wasmuth JD. Kablammo: an interactive, web-based BLAST results visualizer. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1305–1306. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huson DH, Bryant D. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2006;23:254–267. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All raw data were previously reported4. The quinoa chloroplast and mitochondrial genome assemblies and annotations have been uploaded to NCBI under GenBank accession numbers MK159176 and MK182703.